In addition, Fordham leaped to No. 57 in the U.S. News & World Report rankings of the best colleges for veterans, released earlier this fall.

The two rankings reflect Fordham’s many efforts to meet all student veterans’ needs—from career development to health and wellness to help with the transition to college life, said Matthew Butler, PCS ’16, senior director of the Office of Military and Veterans’ Services at Fordham.

“We’re engaged on multiple fronts,” he said. “We’re not just offering an education but supporting the full student veteran life cycle.”

The recognition coincides with rising enrollment numbers for veterans: The number of new student veterans who enrolled at Fordham this fall is up 131% over fall 2023, and the 470 student veterans and veterans’ dependents now enrolled marks the highest total in at least five years, noted Andrea Marais, Fordham’s director of military and veteran higher education, engagement, and transition.

Free Tuition for Student Vets: No Cap

Likely important for the rankings, Butler said, was Fordham’s decision last year to eliminate its cap on tuition benefits under the federal government’s Yellow Ribbon Program/Post-9/11 G.I. Bill. The University covers 100% of tuition and fees for eligible student veterans or their dependents

He said the Military Times ranking was particularly welcome because of the publication’s presence on military bases and stations around the world. In its ranking, Military Times cited other things like Fordham’s Veterans Promise program, which guarantees undergraduate admission to the School of Professional and Continuing Studies (PCS) for students who graduated from New York high schools with a 3.0 and meet other standards.

Butler also noted Fordham’s career-focused events for student veterans such as the Veterans on Wall Street symposium that Fordham will host on Nov. 7. “Veterans make great hires,” said Butler. “They can make good decisions under pressure, they know how to build a team, and they are not afraid of hard work.”

Commander’s Cup

The Military Times ranking closely follows an event that highlighted the University’s tightly knit military-connected community. On Saturday, Oct. 26, Fordham hosted nearly 700 students in Junior ROTC programs from 17 area high schools for the annual Commander’s Cup competition.

The event included drill competitions, physical fitness tests, and tours of Fordham’s Rose Hill campus, as well as opportunities to learn about the ROTC program at Fordham and its scholarship opportunities, said Lt. Col. Rob Parsons, professor of military science at Fordham.

Students at the event were able to see that there’s “an affordable way to go to school and continue to serve,” he said.

“I don’t think it can be overstated how robust and integrated the veterans community in New York is, and how many ties exist to Fordham and Fordham grads,” he said.

Student Veterans of America Build Community

Members of Fordham’s Student Veterans of America chapter volunteered at the event, fielding questions from JROTC members, said Rico Lucenti, a student in PCS and chapter member.

“A lot of kids came up to the booth asking about the veteran presence and military-connected families on Fordham’s campus and what Fordham is doing for those families and students,” he said.

Jorge Ferrara, a PCS student and SVA chapter president, said the chapter arranges service and social events that help student veterans transition to college.

“What we’re doing is trying to establish a sense of community and bring everybody together so everybody knows we’re all going through the same thing,” he said.

A Veterans Day Mass will be celebrated at the Rose Hill campus on Sunday, Nov. 10, the day before Veterans Day. Other upcoming events for Fordham’s student-veteran community include the RamVets Fall Social on Friday, Nov. 8.

Navy JROTC members in formation at the Commander’s Cup at Fordham on Oct. 26

Both changes, taking effect Aug. 1, ensure that eligible beneficiaries will always have their entire tuition covered at Fordham, as they do now, and will never have to worry about the University running out of seats for them.

The changes “underscore Fordham’s commitment to serving those who serve our country,” said Andrea Marais, Fordham’s director of military and veteran higher education, engagement, and transition.

Eliminating Worry for Veterans

The cap removals are expected to clear up confusion about Fordham’s support for student veterans. For years, the University has covered 100% of tuition and fees for eligible Yellow Ribbon beneficiaries, who also receive a government stipend for books and living expenses.

But service members may never find out about these benefits. Checking out Fordham’s Yellow Ribbon program on the government’s website, they sometimes give up after seeing the caps on tuition coverage and enrollment—even though neither limit has ever been reached.

“Some people may be deterred by the cap, not realizing that our tuition falls below it,” Marais said. “And the posted limit on applicants may sow doubt as well, since there’s no way to know whether the limit has been reached. This announcement eliminates all of that uncertainty.”

Yellow Ribbon Program + G.I. Bill = Full Tuition Coverage

Through the Yellow Ribbon Program, the government partners with private universities to give added funding to veterans who qualify for the full tuition amount ($27,120 per year) offered under the Post-9/11 G.I. Bill.

Fordham’s tuition benefit cap was so high that the University never needed to turn away any eligible veteran—and with the cap gone, it won’t ever need to. That’s good news for service members dealing with financial jitters, said Matthew Butler, PCS ’16, senior director of Fordham’s Office of Military and Veterans Services.

“Veterans aren’t in the position to take any chances” when considering their college costs as they’re transitioning out of the military, he said, also noting that Yellow Ribbon beneficiaries at Fordham receive one of the highest housing allowances in the country.

Michael Condit, a former Army infantryman and recruiter who just completed his bachelor’s degree in economics at Fordham’s School of Professional and Continuing Studies, said veterans may also be looking for a reason to rule themselves out, thinking “oh, I’m not a college person.”

“When you hear that there are caps and restrictions, you might [think], ‘Well, I don’t want to get in line just to be told ‘no,’” he said.

Supportive Community

Assimilating into Fordham after five years of active duty in the Army was “a great experience,” said Miguel Angel-Sandoval, a senior majoring in Real Estate with a minor in economics in the School of Professional and Continuing Studies and a candidate in Fordham’s ROTC program. He’ll be graduating in May with a job already secured at RSM real estate consulting agency.

He was welcomed by members of Fordham’s Student Veterans of America chapter and others who helped erase any feeling of discomfort at being an older student. Coming to Fordham “was the best decision I’ve ever made,” he said.

To learn more about military benefits and opportunities at Fordham, please contact the Fordham Veterans Center at [email protected] or call (212) 636-6433.

]]>On Nov. 2 at Keating Hall, the Fordham Veterans Association hosted two executive leaders from Student Veterans of America (SVA), a nonprofit organization that aids more than 1,500 colleges and 700,000 student veterans across the country. James Schmeling, SVA’s executive vice president, and Jared Lyon, SVA’s president and CEO, gave a talk geared toward faculty and staff at Fordham, which is home to around 500 student veterans and veteran dependants.

The day’s lecture was a personal topic for many in the room, including Matthew Butler, PCS ’16, director of Military and Veterans’ Services at Fordham and a former Marine, and the two guest speakers—both of whom are first-generation college students who served in the military. And, said Butler, who introduced the talk, it was also a chance to remember Fordham’s veterans who died nearly a century ago.

“I would be remiss if I didn’t take a moment to draw your attention to the armistice signed on November 11, 1918—a hundred years ago. I draw your attention to the armistice because of the men from Fordham University who joined the fight in Europe during World War I,” Butler said.

“Several of them didn’t come home … Those service members who fought in the war to end all wars are why we are here today.”

Facts and Figures

Schmeling spoke about the post-9/11 veteran population, their challenges with returning to civilian life, and how colleges and universities can benefit from having veterans in their student body.

“Forty-six percent of post-9/11 veterans are somewhere between 18 and 34,” he said. “That’s the population that’s returning to school.”

These veterans face a variety of challenges when they leave the military: navigating their veterans benefits, finding a job, acclimating to a non-combatant life, struggling with finances, and understanding how to apply their military skills to their new jobs, Schmeling said. But they’re also better students than most people might imagine.

On average, post-9/11 veterans achieve higher educational attainment than earlier generations and the general U.S. population, he said. Forty-one percent of post-9/11 veterans have a college or associate degree. On the other hand, only 28 percent of the total U.S. population have that same level of education. Many student veterans are well-educated, Schmeling said—but most people don’t think they are.

“I’ve just given you the data and the facts,” said Schmeling, who sourced statistics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. Census Bureau, journal studies, and information collected in a collaboration between SVA and the Institute for Veterans and Military Veterans at Syracuse University. Then he paused.

“But these,” he said, introducing his next topic, “are the perceptions. And these perceptions are what are really, really important.”

Fighting Commonly Held Perceptions

Schmeling addressed common perceptions held by veterans, non-veterans, employers, educators, and military spouses. He showed the audience several bar graphs from the 2018 Veterans’ Well-Being Survey, a study of more than 4,500 veterans and non-veterans conducted by Edelman Intelligence, a global communications marketing firm.

Majorities from each population indicated that that they think veterans are more than or equally likely to obtain a bachelor’s degree as non-veterans, he said. However, the same is not true for advanced degrees.

A whopping 70 percent of military spouses said they believe military veterans are less likely than the average citizen to obtain a degree ranked around a Ph.D.

He also noted that 53 percent of employers believe that, compared to non-veterans, most veterans do not have successful careers after they leave military service. And barely half of veterans themselves believe that the majority of veterans have successful careers post-military service.

From Combat to Campus

But student veterans have both facts and data on their side. They’re not only college material—they’re an asset to college classrooms, Schmeling argued.

First off, student veterans aren’t likely to incur much debt. As of May 2018, the post-9/11 G.I. Bill/ Yellow Ribbon program has funded $75 billion for veterans’ tuition, fees, book stipends, and housing allowance, he said. Fordham’s commitment to the Yellow Ribbon program guarantees that all tuition and fees are fully covered for admitted eligible veterans.

Student veterans also bring diversity in age, ethnicity, marital status, and disabilities. In addition, they possess military-honed skills that can transfer to their studies and future jobs: work ethic and discipline, mental toughness, teamwork. And on average, he added, student veterans have a higher GPA than traditional students at four-year-degree-granting institutions nationwide.

“This is contrary to the picture that the media paints—of homelessness, of PTSD, of workplace violence, among other sorts of things,” he said. “Why is that? Well—what sells? A negative story, right?”

Veterans typically do best in colleges and universities that have a good peer support system, advisors, and networking opportunities, Schmeling and Lyon said.

“The number one thing we can provide a student veteran—if you give them this one thing, they’re three times more likely to graduate than anything else—shocks a lot of people. It’s a peer. It’s a friend—someone you can relate to firsthand in that college environment,” Lyon said.

“I started my undergraduate experience at the age of 28 years old at Florida State University,” he said. “And as I looked across a sea of 42,000 undergraduates … I mean, one of these things was not like the other. And that was me.”

Schmeling added that many student veterans he’s spoken with, especially first-generation college students, had no idea they could graduate from college after serving in the military.

“They had no idea they could thrive in an environment like Fordham,” he said. “If you tell them that they can be successful, we convince them that they can be successful, and we continue to invite them to our campuses, they will be successful.”

Anna Ponterosso, university registrar and director of academic records, said she found the lecture to be informative.

Feature photo: Shutterstock; Other photos: Taylor Ha

]]>This past May, Mahlon Bailey, a subway mechanic for the MTA and Property Book Officer in the104th Military Police Battalion in the New York National Guard, joined the ranks of Fordham’s Yellow Ribbon graduates. He recently sat down to talk about how the degree he earned in organizational leadership helped him become an officer.

Listen here:

Full transcript below

Mahlon Bailey: I like to say I’m addicted to service because, I don’t know, I like to help, I like to give, I like to serve, and that’s why I’m still here after 18 years.

Patrick Verel: It’s September, which means students are flocking back to campus after the summer break. At Fordham School of Professional and Continuing Studies, 300 of those enrolled this fall will be participating in the Veterans Administration’s Yellow Ribbon Program, which covers tuition and fees for eligible post 9/11 veterans at select colleges.

This past May, Mahlon Bailey, or just Bailey to his friends, a subway mechanic for the MTA and property book officer in the 104th Military Police Battalion in the New York National Guard, joined the ranks of Yellow Ribbon graduates. He recently sat down to talk about how the degree he earned in organizational leadership helped him become an officer.

I’m Patrick Verel and this is Fordham news.

Talk to me about your time in the military. Now, you enlisted in the marine corps when you were 17, correct?

Mahlon Bailey: I was actually laying in my bed thinking about what to do next and I got a call from a Marine Corps recruiter. At the time I was not interested in going college, but I didn’t want to not go to college at all, so he offered the possibility of learning a technical skill and going to school later on, and I said, “Perfect.”

Patrick Verel: Why did you feel like it was what you needed at time?

Mahlon Bailey: By the time I got to 11th grade, I was burnt out. I was tired of school, so I wanted to take a break, but I kept hearing, if people that take a break never go back to school, or they plan on taking a break and they just don’t go continue with college and that’s a source of pride for my parents, so I said, “I’m definitely going to school, because they want me to go to the college.” Both of them are college graduates.

I then said I was a jet engine mechanic, which was a technical skill that would have been marketable after I leave, and then I got out. And I switched to the National Guard.

Patrick Verel: I once heard you say that you quote/unquote “live logistics.” What do you mean by that exactly?

Mahlon Bailey: It’s just every part of my life, basically. I like to make complicated things simple. You remember superstorm Sandy?

Patrick Verel: I do.

Mahlon Bailey: Okay, so the governor activated the state, the Guard in the state, and just brought a bunch of National Guard soldiers together and we were in charge for the relief effort. I was a platoon leader for that. Well, I had to get all those people on the same page and say, “Listen, we understand that … Well, I understand that you might be going through also. However, we need to help these people. Right? I’m going to my best to take care of you and your personal issues, but we need to focus on this mission.”

It takes making a complicated thing simple to have those, a platoon full of soldiers, execute that mission effectively. I like to say I’m addicted to service, because I, I don’t know, I just like to help, I like to give, I like to serve, and that’s why I’m still here after 18 years.

Patrick Verel: Why did you want to get a college degree in 2014 and why did you come to Fordham?

Mahlon Bailey: That was one of the promises my recruiter made to my mother, right? “He can get it,” because that was her main focus. “Can he still get a degree?” The Yellow Ribbon events encourage education and transitioning from being on a deployment to focusing on bettering ourselves.

Also, my father had a health scare, right? I said, “I have to get this before it’s too late.” The fact that Fordham was a Yellow Ribbon school, that’s what said, “All right. This is the place I need to be.”

Patrick Verel: What was it like to go back to school after all those years?

Mahlon Bailey: Challenging.

Patrick Verel: Yeah? How so?

Mahlon Bailey: I didn’t know how to write. I definitely did not know how to write. I thought I was a pretty smart person, but professor Windholz basically shot that down, definitely. I thank professor Windholz for being as demanding as he was because he set me up for the rest of my Fordham life, but that was the most challenging course I took, because at the time, I was still working full-time, going to school, and I remembered getting a Monster or a Red Bull or doing push-ups just to stay awake to write this paper that he, specifically the way he said to write it.

Patrick Verel: Wow, it must have been overwhelming when you actually got to get your degree in May.

Mahlon Bailey: Yes. Yes. It was. My parents were there. It was definitely overwhelming. It was, it was similar to when I graduated boot camp.

Patrick Verel: For people who aren’t familiar with the military, what is a property book officer?

Mahlon Bailey: The technical term for my position is property accounting technician. I account for property on the level in a battalion.

Patrick Verel: So, you’re gonna keep track of every tank, every gun, every toilet seat, everything that belongs in that battalion.

Mahlon Bailey: Keep track, yes.

Patrick Verel: Make sure it doesn’t walk off.

Mahlon Bailey: Yes, that’s a good way to think about it.

Patrick Verel: You’re making a big transition because you had been working for the MTA, and you previously had been enlisted, and this is going to help you become an officer. Is that a way to think about it?

Mahlon Bailey: So, I’m a reserve, and I work for the MTA. I fix trains for the MTA. That’s my civilian job. My military career, ever since I’ve been in the Marine Corps, I was dealing with logistics, so when I switched to the Guard, continued with logistics, that experience is what led to become a warrant officer, and having a college degree in organizational leadership as a logistician and also as an officer, completes the package.

]]>Fordham has been ranked regularly on the list, thanks to the diverse and comprehensive programs provided by the FordhamVets Initiative — which helps veterans transition from the military to college life — and to the financial support the school provides through the Yellow Ribbon Program.

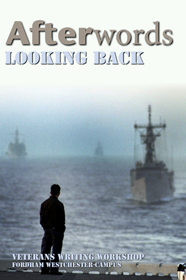

One program that has been particular helpful to Fordham veterans is the Veterans Writing Workshop, which has been held at Fordham’s Westchester campus since 2010 and recently expanded to the Lincoln Center campus. The workshops are held three times per year at both campuses.

One program that has been particular helpful to Fordham veterans is the Veterans Writing Workshop, which has been held at Fordham’s Westchester campus since 2010 and recently expanded to the Lincoln Center campus. The workshops are held three times per year at both campuses.

Veterans meet weekly to learn about and practice the craft of writing and to receive feedback and support from their peers. The workshop is “intensive and creative,” said founder and instructor David Surface, and functions primarily as a writing class rather than as a support group or a therapy session. Even so, it’s difficult to separate the therapeutic value of such a group from its artistic value.

“Writing can be healing,” Surface said. “When you write about your experiences, particularly in a serious, intensive, craft-based way, there’s something that happens that doesn’t happen in a therapy session or support group. It has to do with taking mastery of your experience, or taking control of your experience in a way.”

The veterans are not required to write specifically about their experience at war because not all of them are ready to put their trauma into words, Surface said. Instead, they write about whatever inspires them in the moment, whether it’s a memory from the battlefield or a hike with family.

At the conclusion of the workshop, the veterans’ writings are published as an anthology, which the veterans share in public readings and events. In addition to preserving and celebrating their writing, Surface said, the book helps to raise awareness about veterans’ experiences by hearing it in the service members’ own words. This year’s book, Afterwords: Looking Back, marks the 15th edition of the publication.

“There’s a lot of talk these day about the military/civilian divide in our country. Civilians don’t understand what veterans have experienced and vice versa,” he said. “But having the veterans themselves write about these experiences is one of the best ways to help narrow that gap.”

“There’s a lot of talk these day about the military/civilian divide in our country. Civilians don’t understand what veterans have experienced and vice versa,” he said. “But having the veterans themselves write about these experiences is one of the best ways to help narrow that gap.”

The Veterans Writing Workshop was developed in 2010 through collaboration between Arts Westchester (formerly the County Arts Council), the Hudson Valley Writers Center, and Fordham University Westchester as part of the National Endowment for the Arts’ The Big Read Program. Free of charge, the workshop series is open to veterans from every conflict.

Often, Surface said, a workshop will find veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan sitting side by side with veterans from Korea, Vietnam, and even World War II.

“They talk about their stories, about their feelings,” he said. “There is a comradeship that forms.”

Over and over again he has seen the veterans draw on that natural bond to help each other not only with their writing, but also with the struggles they face in the aftermath of war. He recalled an instance when one veteran decided to write about an event that had triggered a severe post-traumatic stress disorder. When the writing process became distressing for him, another veteran in the workshop offered support.

“He just sat with him while he wrote the story,” Surface said. “They help each other through these experiences.”

In addition to continuing the workshops at Fordham’s Westchester and Lincoln Center campuses, Surface will be running a Women’s Veterans Writing Workshop starting this spring at Arts Westchester. And in February, a Families of Veterans Writing Workshop will begin at Fordham Westchester for friends, family members, and supporters of military personnel.

“What I hope they learn is that their own experiences — their own memories, feelings, and thoughts — are valid,” Surface said. “They don’t need to look outside of themselves for material to write about. I just try to give them skills and tools to do that.”

]]>