Walsh worked for more than two decades at the library’s electronic information center, where she had many responsibilities, including scheduling and supervising student workers. She also maintained an encyclopedic knowledge of the library’s spaces and their respective schedules.

“She knew the geography of the building perhaps better than anybody,” said Linda Loschiavo, director of University Libraries. “She seemed to know every member of the University administration, every dean, every chair. She knew every name that popped up.”

When a flood on the library’s lower level caused the staff to temporarily relocate in 2021, Loschiavo spent the year sharing her office with Walsh. She described the experience as “the silver lining” of a difficult time for the library staff.

“Jean was one of the kindest individuals I’ve ever met,” Loschiavo said.

Walsh’s daughter Jeannette Ginther also reflected on her mom’s giving nature.

“She was just so caring and so selfless,” she said. “She really put everybody in her life before herself.”

Walsh was born in the Bronx to Victor and Lucy Spaccarelli. She owned Jean’s Hallmark Shop in the Galleria at White Plains for more than 10 years before joining the staff at the William D. Walsh Library on the Rose Hill campus, where she worked for 21 years.

Walsh’s connections to Fordham began with her father, Victor, a master bricklayer and stonemason who did extensive work on the Rose Hill campus, including building the very library where his daughter worked.

“He had a hand on a stone of every building of the Rose Hill campus,” her son, Thomas Walsh Jr., FCRH ’07, said of his late grandfather.

Her brothers Victor Jr. and John Spaccarelli, the current director of special projects and facilities at Fordham; her husband Thomas Walsh; and son Thomas Jr. have been decade-long employees of Fordham in various fields, including facilities and project management.

“Between Victor Sr., his son, John, and myself, we have worked on every building on all three campuses,” said Thomas Walsh, adding that the family history was a great source of Jean’s pride in being a Fordham employee.

“My mom’s first priority was always her family,” Ginther said. “She also treated her employees and her coworkers like family.”

Walsh’s passion was cooking—a love that she shared with friends and family alike by hosting big holiday dinners and frequently bringing baked goods for her student workers and colleagues at the library to enjoy.

But Walsh’s greatest joy was watching her grandchildren, Richie, Justin, and Natasha, grow up. Walsh was a constant presence in their lives and spoke of them so often that fellow Fordham staff members felt they knew them personally.

“At her wake and her funeral, there were so many Fordham colleagues that came,” said Kristina Karnovsky, Walsh’s youngest daughter. “When they had a chance to meet my children and my sister’s children, it was like they already knew them because she spoke of them so often and had their pictures at her desk. ”

A funeral Mass was held at St. Columba Church in Hopewell Junction on Feb 12. Donations in her memory can be made to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital or the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

“You remember people, I think, for how they made you feel,” Karnovsky said of the impact her mother had. “And she made everyone feel so loved.”

]]>It was hard to imagine that in 1994, this was just an empty patch of land, and not a five-story, 240,000 square-foot anchor of the Rose Hill campus’ southwest corner.

This year, the library is celebrating the 25th anniversary of the day it opened its doors to the Fordham community.

The Paradox of Libraries

For Linda LoSchiavo, TMC ’72, director of Fordham Libraries, the anniversary has been an occasion for reflections on the library’s ultimate mission. She noted that libraries have always been a bit of a paradox, and Fordham’s is no exception.

“On the one hand, it’s perceived as somewhat of a cloister. It’s a place of quiet study and meditation. It’s kind of a retreat from the clamor of the world,” she said.

“But in fact, we’re also functional. Every day, the doors open, and the University enters. We’ve got students coming in. They might work alone, but they also form communities, they make connections, and all the learning is shared. So, we have to fulfill those two functions.”

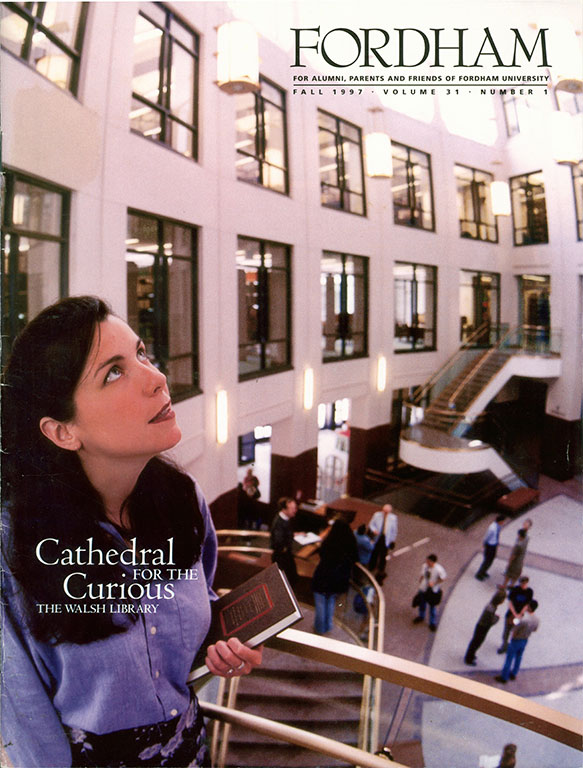

‘Cathedral for the Curious’

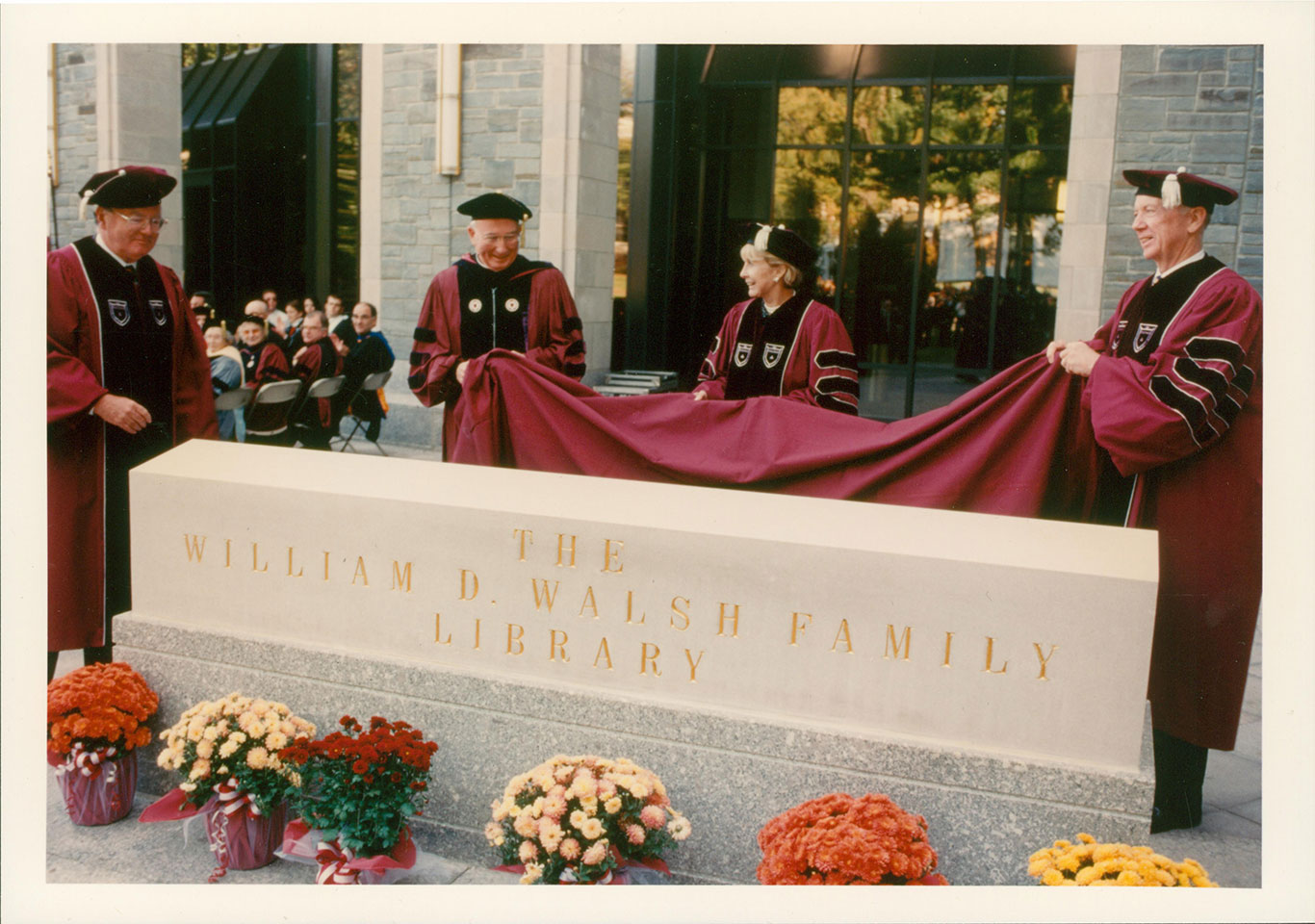

The William D. Walsh Family Library opening ceremony took place on October 17, 1997, after just under three years of construction. It cost $54 million, $10.5 million of which came from William D. Walsh, FCRH ’51.

Joseph O’Hare, S.J., Fordham’s president at the time, presided over the ceremony. He was joined by John Cardinal O’Connor, who hailed the structure as “one of the most enriching facilities that at least I have seen since I have been Archbishop of New York.”

That fall, Fordham Magazine’s September issue was devoted to the new library, which it dubbed the “Cathedral for the Curious.” O’Hare said it successfully integrated with the Neo-Gothic architecture of the campus’ signature buildings, yet was contemporary in its look.

“[It is] not a stone fortress, but rather a window of welcome of the University’s life of learnings,” he wrote in the magazine’s introduction.

The new building was high-tech for its time, housing 350 computers, video equipment, and study carrels quipped for laptop use. Resources were also shared beyond the Fordham community; with help from a New York state grant, a new technology center provided software training and teachers in the Bronx and lower Westchester.

An Operation Scattered Around Rose Hill

When Walsh Library opened, LoSchiavo did not work there, as she was director of Quinn Library at Lincoln Center at the time. But she had worked at the Rose Hill campus in the years before it was completed. When she joined Fordham in 1975, the University had long outgrown Duane Library, which opened in 1926 with just 31,500 square feet of space and seating for 504 patrons. As a result, library operations were scattered among five different buildings. Chemistry, biology, and physics books were stored in three separate locations before they were combined into one science library in 1968, when John Mulcahy Hall opened. And the library’s cataloguing and acquisitions departments shared space with the periodicals collection in the basement of Keating Hall, where LoSchiavo worked for a time.

When Walsh opened its doors, it not only eliminated inefficiencies that came from being spread out, she said, it also showed how the right space makes it possible for a library to evolve to meet the needs of its patrons.

In fact, she noted that shortly after it opened, administrators realized that the first-floor periodicals reading room, where physical copies of journals and magazines sat neatly arrayed on shelves, had been rendered obsolete by electronic publishing. Less than a year later, the space was transformed into the Museum of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Art.

Designed for Change

LoSchiavo called the changes, which have taken place in innumerable instances small and large throughout the building, are the result of “controlled flexibility” inherent in the blueprints drawn up by the building’s architect, Shepley Bulfinch.

Photocopier rooms? Those have become group study rooms. Offices for other divisions around the university? Three of them were combined into one unified space now occupied by a writing center. This summer, a section of the basement that was once storage for printed copies of dissertations was transformed into the Learning & Innovative Technology Environment (LITE) center. Last month, a fourth-floor reference desk that was a holdover from the separate science library was christened the Henry S. Miller Judaica Research Room.

It’s all part of the push and pull of simultaneously preserving the past while promoting the future.

“When you look at stacks, what you’re seeing is immortality. And then you get these students coming in—and they can be loud, but they’re vibrant. And there’s your future right there, coming through the door,” she said.

“When we opened the lower level, we had an electronic information center, which at the time, oh my God, was that revolutionary. We had all these computers and computerized databases. But now, the term electronic information center is really dated. I mean, the whole building is an electronic information center.”

A Centerpiece for Sustainability

Not all the changes to the building have come from shifting research and studying habits. Given its size and its hours of operation, the library is also the biggest energy user on campus, and is thus a centerpiece of Fordham’s sustainability efforts. In 2010, it became the site of the University’s first solar panel array, and in 2019, clean energy servers installed there helped Fordham offset more than 300 metric tons of carbon dioxide each year.

As the University continues with efforts to reduce its carbon footprint by 40% by 2030, Walsh Library will stay in the spotlight; this year it will be the first building to undergo an energy audit to determine what can be done to further shrink its energy consumption.

For LoSchiavo, it’s all part of the job.

“It used to be that people felt that things changed very slowly in libraries, but as a matter of fact, they don’t. They actually change on the rapid side, and it’s actually hard for us sometimes to keep up with the new ways that things are being delivered,” said LoSchiavo, whose team celebrated the building’s silver anniversary by creating Walsh25, a campaign featuring a resource guide, giveaways, displays, and blog postings.

“But what we’ve found over 25 years is that students still need information. The faculty still need information. They still need a place to study. They still need a place to read. They need a place to do research. They need a place to collaborate with one another. They still need the librarians to guide them through the process.”

Photo by Patrick Verel

]]>

Those special items will be available on Tuesday, Nov. 8, from 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. in the O’Hare Room, in Special Collections at Walsh Library, where visitors can hold them and learn more about them. They’ll be presented by Jan Graffius, Ph.D., the curator of collections at Stonyhurst College, Lancashire, who brought them to New York City as a complement to the exhibit on the Tudors at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She arrived at Fordham on Nov. 5 with 10 or so 15th- and 16th-century books and items owned by Stonyhurst, Campion Hall—the Jesuit hall at Oxford University, and the British Province of Jesuits.

Other objects currently in Walsh Library include Katherine Bray’s Book of Hours, St. Campion’s Decem Rationes, and the St. George reliquary of Sir Thomas More. All of the objects that will be shown at Fordham are featured in this short video.

Graffius spoke to a small group of library staff and administrators on the morning of Nov. 7.

“Perhaps the most powerful impact of Dr. Graffius’ visit to Walsh Library was her eagerness not simply to share the precious objects she had brought with her, but to give us an almost intimate connection with them,” said Linda LoSchiavo, director of Fordham Libraries.

“Without a piece of glass or a velvet rope separating us from the prayerbook of a Tudor monarch, or the adolescent scrawls in a text belonging to the young John and Charles Carroll, we were able to stand only inches away from items that, under any other circumstances, we would have to cross an entire ocean to get a glimpse of. Jan Graffius’ encyclopedic knowledge of her collection and the history surrounding it is matched only by her enthusiasm and warmth as a speaker.”

Graffius will be bringing the items to other locations in New York City and the U.S., including the Church of Ignatius Loyola in Manhattan. Though these items will not be on display at the Met, Graffius did contribute to the museum’s exhibit by installing a cope (vestment) belonging to Henry VII, which was contributed but the British Province of Jesuits. The Met exhibit, titled The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England, will be on display until Jan. 8.

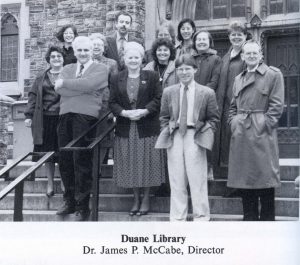

“Jim was a dedicated University librarian and administrator whose can-do spirit served the University well during a period of expansion and growth,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “He brought Fordham from an era of card catalogs to the full splendor of the information age. Thanks to his efforts, our students and faculty may draw from a far deeper well of information in pursuit of learning and scholarship.”

McCabe became the director of libraries on August 13, 1990. Until he retired in 2012, he helped Fordham libraries reach new heights—literally. He was an integral part of the design and construction process for the William D. Walsh Library, a five-floor modern Gothic style building that has housed more than 1,000,000 volumes since it was completed in 1997. The building was classified as the fourth largest library in New York in 2013 and featured in The New York Times.

“Jim McCabe’s strong vision for the future combined with his deep knowledge and respect for traditional practices made him the perfect person to lead the Fordham libraries into the 21st century. But Jim was much more than that,” said Linda LoSchiavo, director of libraries at Fordham, who succeeded McCabe. “A gentle, gracious man, with a quick sense of humor, he was esteemed and admired by his staff, his colleagues at Fordham, and by the academic library community as a whole. The University has lost a quiet hero, and those of us fortunate enough to work closely with him have lost a friend.”

Maryanne Kowaleski, Ph.D., retired Joseph Fitzpatrick, S.J. distinguished professor emerita of history and medieval studies, recalled McCabe’s leadership when Fordham moved its collections from Duane Library, which used to be the main library for the Rose Hill campus.

“Jim McCabe came to Fordham at a crucial juncture, when he oversaw the complicated move to the new Walsh Library and facilitated the transition to electronic resources that we take for granted today,” Kowaleski said. “He was a kind and gentle man who led by example, taking his turn in the labor involved in moving the collection. He also went out of his way to meet and socialize with faculty, working to open up fruitful lines of communication between Fordham’s teachers and librarians.”

‘Let’s Do It’: A Librarian and Leader in the Digital Age

McCabe was a leader in the university library community during a time when technology began to dramatically change the ways libraries worked. At the beginning of the new millennium, he introduced the complete automation system to Fordham’s libraries, which included the electronic catalogue system and the library’s back-office operations. This helped librarians work more efficiently and gave students quicker access to resources. In addition, he helped promote one of the library’s most popular services, the electronic reserve room software. Similar to the BlackBoard Learn system currently used by faculty and staff, the electronic reserve room software was used to help faculty create course pages and upload resources for their students.

“The immediate, enthusiastic acceptance of electronic reserves is proof that it is a program whose time had come. It is a fine example of how the Internet can make our lives and work a little easier, and save time and energy,” he wrote in a 2000 piece for Inside Fordham Libraries.

In addition, he served as a link between Fordham and New York Libraries in his role as president of two local library organizations. He served on the Metropolitan New York Library Council’s Board of Trustees, where he helped foster conversations about important library and information issues, and on the Historical Preservation Commission for Westfield, New Jersey, where he helped to preserve the town’s historical sites and landmarks.

McCabe was not only a librarian, but also an author. He wrote Critical Guide to Catholic Reference Books (Libraries Unlimited, 1971), a series of annotated entries on topics related to the Catholic Church, including liturgy, social sciences, and literature.

“[He brought] digital resources of bewildering variety to library users within and without our library buildings. He has done this while substantially increasing the size and scope of our print collections, improving staff morale, increasing the hours and quality of library service to library users, and winning the respect, admiration, and affection of the Fordham community,” read a citation in a 2010 convocation booklet that recognized 20 years of his service to Fordham. “Whenever he encounters an opportunity to provide a new service or improve an old one, his reaction has been, ‘let’s do it.’”

In the early 2000s, he named two hawks that once frequented the Rose Hill campus and the New York Botanical Garden. The first hawk was named Rose after the Rose Hill campus; the second hawk was named Hawkeye Pierce, in honor of the character played by Fordham alumnus Alan Alda on the M.A.S.H. television series.

‘It Isn’t Raining in Our Hearts’

McCabe was born on May 24, 1937 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Felix and Josephine McCabe. His father was a lineman for a telephone company and his mother was a nurse. He graduated summa cum laude from Niagara University in 1963 and earned three graduate degrees at the University of Michigan: a master’s in English literature, a master’s in library science, and a doctorate. For more than two decades, he served as library director at Allentown College of St. Francis de Sales in Pennsylvania, now known as DeSales University, where he oversaw the conceptualization and construction of a new library facility. Right before his appointment to Fordham, he served as the acting library director for Muhlenberg-Cedar Crest Colleges Libraries in Pennsylvania.

His friend for nearly 40 years, Romain Frugé, said McCabe was a beloved member of the theatre community at DeSales University, where he manned the lighting booths during shows and served as an academic mentor and confidant for students. McCabe was also a staunch supporter of students’ work. He flew to London and Japan to watch Frugé perform in several musicals, said Frugé. And no matter where he went, McCabe had a positive outlook on life.

“Whenever it was raining, Jim would say, ‘Well, it isn’t raining in our hearts,’” said Frugé, who was a student at DeSales University, where McCabe worked as library director. “He was always a real positive force.”

McCabe never had children of his own, but he was close to his four siblings and their children. For many years, he spearheaded an annual family picnic in Manhattan, said his niece Jennifer Carlin. He loved everything about the city, especially cheap tickets to Broadway shows, and he walked like a classic New Yorker at 10 miles per hour, said his nephew Felix Carroll. And he always appreciated the little things.

“He gave me a really great piece of advice when I was in my early 20s,” Carroll said. “I was moving all over the place, and I couldn’t settle on anything … He told me to stop and take delight in the world. We can be worried, but we’re supposed to find joy, too, and that’s found in everyday things.”

McCabe is survived by two siblings, Aileen McClure and John McCabe, and numerous nieces and nephews; he is predeceased by two siblings, Francis McCabe and Ann Carroll. A funeral Mass will be held on Sept. 24 at 11 a.m. at St. Ephrem Catholic Church located at 5400 Hulmeville Road, Bensalem, Pennsylvania, 19020. The Mass begins at 11 a.m., but family and friends are invited to gather at the church an hour earlier. Interment will follow at Resurrection Cemetery.

The funeral service will also be streamed, beginning at 10 a.m. on Sept. 24. To obtain the link to view the service, contact Jean Walsh, senior executive secretary at the Walsh Library, at [email protected] by Sept. 23 at 5 p.m., latest. You can view live or at your own convenience.

In lieu of flowers, donations in McCabe’s honor may be made to the book fund at Fordham University Library.

By check: Payable to Fordham University Library

Attn. Linda LoSchiavo

Director of Libraries

Walsh Library, Suite 219

441 East Fordham Road

Bronx, NY 10458

Online: www.fordham.edu/give. Several funds are listed. Click OTHER, then indicate “Fordham University Library, in honor of James McCabe.”

]]>Hendrik Hameeuw of Katholieke Universiteit Deuven originally came to the U.S. to demo the Portable Light Dome Scanner for the curators and researchers at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Through a connection that Lisa Lancia, director of international initiatives at the Fordham Libraries, had with a Belgian program, Hameeuw offered to give Fordham faculty and staff a demo of the device on campus.

Offering a state-of-the-art approach to looking at cultural heritage, the scanner helps others visualize the topography of medieval book illuminations, stamps, inks, seals, and bookbinding stamps in two-dimensional.

The demonstration included Hameeuw’s presentation on advanced imaging techniques followed by test scans of items selected from Fordham Library’s Special Collections.

Director of University Libraries Linda LoSchiavo called the technology “thrilling.”

“Digitization is an important issue for us, not only in terms of preserving Fordham’s past,” she said, “but in the that it allows us to present research in a truly unique way.”

–Lindsey Fritz

]]>“We have some great examples of what life really was like for the ancients,” said Michael Sheridan, a member of the Class of 2018 double-majoring in history and art history, and one of the 18 students who took the class. “Most universities don’t have anything like this, so we really are lucky to have this collection here.”

The exhibit ran from May 6 through August 15. Students selected the objects—including imperial portraits, luxury household items, coins, and painted pottery—from the 260-plus antiquities in the museum. They researched the objects’ history, wrote the text to accompany them, and helped design the display in a newly created gallery at the museum.

One of the students in the class, Michael Ceraso, even teamed up with another Fordham student, Michael Gonzales, to develop an app for the exhibit that ran on three iPods in the gallery.

“They were involved every step of the way,” said Jennifer Udell, PhD, curator of university art and the seminar’s instructor, who realized her longstanding idea for the project thanks to a gift from Fordham Trustee Fellow Robert F. Long, GABELLI ’63, and his wife, Katherine G. Long.

01

01

Askos (flask) in the form of a reclining satyr

Roman, ca. 1st century C.E.

Bronze, l: 5¼ in. (13.3 cm)

02

02

Oil lamp inscribed “The light of Christ shines for all”

Byzantine, ca. 5th century C.E.

Terracotta, l (from handle to nozzle): 3¼ in. (8.25 cm)

03

03

Terracotta transport amphora

Greek or Roman, ca. 5th century B.C.E. to 1st century C.E.

Terracotta, h: 27 in. (68.5 cm)

“This jar served a concrete, utilitarian purpose from the time it was made until the day that it finally fell prey to the waves of the wine-dark Mediterranean. The barnacles make for an interesting aesthetic that might grab your attention for a moment or two, but [they also] tell us so much about the perils and realities of life and trade in the ancient Mediterranean.”

—Christopher Boland, Class of 2016, math major and theology minor

04

04

Patera (shallow bowl) with knob handles

Greek, South Italian, Apulian, red-figure, ca. 340 B.C.E.

Terracotta, d: 22 in. (55.89 cm)

“This particular patera is among the largest objects in the collection, and I, like others, am drawn to this sort of scale. It depicts the Amazonomachy, an ancient battle between the Greeks and the Amazons, a fierce race of warrior women emblematic of ancient feminism and girl power.”

—Maria Victoria Alicia Recinto, Class of 2016, art history and anthropology major

05

05

Fish plate

Greek, South Italian, Campainian, red-figure, Late Classical, ca. 340 to 320 B.C.E.

Terracotta, d: 6¾ in. (17.1 cm)

“This plate conveys the fisherman in an everyday life. It is easy to envision a small enclave of aquatic-based communities along the Mediterranean coast, coming home after a day at sea, and cooking the day’s catch. It is easy to imagine the smell of mackerel, sea bass, octopus, and other marine delicacies grilled and served on this plate with the pungent dressing of fresh olive oil, the scent carried away on a sea breeze after a hard day’s work.”

—Owen Haffey, Class of 2019, English major

06

06

Kernos (vase for multiple offerings with mold made figural protomes)

Greek, South Italian, Campanian, Late Classical, ca. late 4th century B.C.E.

Terracotta, h: 6¼ in. (15.9 cm)

07

07

Kylix (drinking cup with stem)

Greek, Attic, Late Archaic, red-figure, ca. 520 to 510 B.C.E.

Attributed to the Painter of Berlin 2268

Terracotta, d: 10½ in. (26.7 cm)

“I’ve always been amused by these dishes and how they’re used as drinking cups. … This finely made image of Dionysus shows him in a lunge gazing back at his own (possibly empty) goblet. When you finish your wine and are faced with the god of wine himself, it seems like a pretty good sign to fill up your kylix again.”

—Emma Cleary, Class of 2016, chemistry major and art history minor

08

08

Kylix (drinking cup with stem)

Etruscan, Archaic, black-figure, ca. 530 B.C.E.

Terracotta, d: 41/8 in. (10.5 cm)

09

09

Athenian tetradrachm

Greek, Attic, Classical, 430 to 413 B.C.E.

Silver, d: 7/8 in. (2.2 cm)

“What originally attracted me to this coin was the fact that it featured the portrait of the goddess Athena instead of a historical Greek ruler. This fact led me to wonder about both the representation of mythological figures and the representation of women on coins. … I wonder who might’ve used this coin and what they might’ve bought with it. It’s fascinating to think that we still read this piece of metal as a coin, but it now carries the monetary value of an ancient artifact instead of its original value as a circulated coin.”

—Katie Fredericks, Class of 2016, art history major

10

10

Coin of Lucilla

Struck under Lucius Verus, ca. 164 to 183, C.E., Roman

Bronze, d: 1¼ in. (3.1 cm)

“Lucilla was a Roman empress who was executed after she made a failed attempt to assassinate her brother, who was the Roman emperor at the time. Of course the coin was made before she fell out of favor, but how has it survived this long? I assumed the Romans would’ve melted down many coins depicting Lucilla in order to reuse the bronze as they so often did, and I think it’s amazing that we get the chance to get up close to this ancient scandal.”

—Katie Fredericks, Class of 2016, art history major

11

11

Lebes gamikos (wedding vase)

Greek, South Italian, Apulian, Late Classical, red-figure, ca. 340 B.C.E.

Terracotta, h: 14¼ in. (36.2 cm)

“One of my favorite things to do when I’m interacting with ancient artifacts is to imagine the stories of the objects and the people who used them. How were [they] like me and how were they different? Who has touched and used this object? What was the wedding like? Was it a perfect ceremony or did anything go disastrously or hilariously wrong? What was the couple like? Were they in love or was the marriage motivated by other factors? Asking such questions really brings these objects to life for me and lets me look at them in a whole new way.”

—Sarah Homer, Class of 2016, English major and music minor

12

12

Engraved mirror

Etruscan, Late Classical, 4th century B.C.E.

Bronze, h: 11 in. (28 cm)

“The engraving on the mirror shows three goddesses: Uni, Turan, and Mea, whose Greek names are Hera, Aphrodite, and Athena, respectively. Although the goddesses have Etruscan names, they are the same ones involved in the incident which incited the Trojan War. According to the myth, three goddesses were attending the nuptials of Peleas and Thetis, when a wedding crasher, Eris, threw a golden apple with the label ‘to the fairest.’ The goddesses fought over this apple and thus over who was the most beautiful. So the fact that this engraving is placed on a mirror is very interesting, because it is an object of vanity.”

—Jane Parisi, Class of 2019, classical languages major

13

13

Torso of Herakles

Roman, Imperial, ca. 1st to 2nd century C.E.

Marble, h: 15¼ in. (38.7 cm)

“When I was younger, the legend of Herakles was always one of my favorite tales from antiquity, and this and the presence of drapery are what initially attracted me to this figure. I am taking my fashion minor at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus and, as a student of fashion, the classic Greek drapery and the beautiful form of the sculpture called to me as soon as I saw it.”

—Hans Singer, Class of 2018, art history major and fashion studies minor

14

14

Hydria (water jar)

Greek, Attic, Late Archaic, black-figure, ca. 520 to 510 B.C.E.

Terracotta, h: 19 in. (48.2 cm)

“This is truly a prime example of high-quality Attic vases. The scenes are brilliant and reflect the tendency of vase painters to encapsulate an entire myth through just a few images. Here we have the most popular myth: the 12 labors of Herakles. … Viewers are shown the beginning and the end of Herakles’ story. It’s one complete beautiful cycle.”

—Masha Bychkova, Class of 2018, double major in classical languages and classical civilizations, with a minor in visual arts

15

15

Portrait of the Emperor Caracalla as a youth

Roman, Severan, 198 to 204 C.E.

Bronze, h: 11½ in. (27 cm)

“I was first attracted to this portrait because it’s bronze, which is rare in ancient sculpture, and also because there are few portraits of Caracalla as a child. It’s not just a portrait of a child but also effectively a portrait of a mass murderer, a delusional religious fanatic, and a mentally ill person. At the same time, it is a portrait of the emperor who would become responsible for the bath houses in Rome and the Edict of 212, which granted Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. This sculpture gives insight into the human condition. This is a man who lived thousands of years before our time, yet embodies the same emotionality, conflicts, and mortality of humans in the 21st century: family power struggles, envy and insecurity, murderous rage, religious fanaticism and superstition, and celebrity obsession.”

—Olivia Ling, Class of 2017, classical languages major

16

16

Portrait of a Severan woman

Roman, Severan, ca. 220 to 222 C.E.

Marble, h: 21 7/8 in. (55.4 cm)

“I was initially attracted to the portrait bust of the Severan woman because of my background in working with Roman imperial commemorative statues that were meant to honor prominent societal women. These statues were representative of the changing atmosphere in ancient times, one in which women possessed the ability to honor their status in society as much as their male counterparts. I was also interested in the statue because of its current location in the museum, since it’s right next to the entrance and it’s one of the first subjects visitors see.”

—Simek Shropshire, Class of 2017, art history and English double major

17

17

Cylindrical krater (wide mouth vessel) and lid

Etruscan, Archaic, white-on-red ware, ca. 650 B.C.E.

Terracotta, impasto, h: 21 in. (53.3 cm)

18

18

Ossuary and lid

Etruscan, Archaic, white-on-red ware, ca. 580 B.C.E.

Terracotta, impasto, h: 16 in. (40.6 cm)

19 to 23

19 to 23

Antefixes in the form of a kneeling kore (maiden) and of women’s heads

Etruscan, Late Archaic to Early Classical, ca. 500 to 480 B.C.E.

Terracotta, h: 11 in. to 20½ in. (28 cm to 52 cm)

“These women represent maenads, who are the servants of the god of food and wine, Dionysus. It is said that Dionysus put these women under a drunken spell and, as a result, they became praised and protective, which is the role they play as they watch those who enter temples. This would bother most feminists, because it indicates a man’s power over women. However, I think that they exude the power and fury of women. Their intense eyes and beauty would force anyone to enter with caution and reverence.”

—Madeline Locher, Class of 2018, art history major

24

24

Ram’s head drinking cup

Greek, South Italian, Apulian,

mold and wheel-made, Late Classical,

5th to 4th century B.C.E.

Terracotta, l: 7½ in. (19 cm)

“The beauty of [this cup]lies in its simplicity. It’s terracotta and unpainted, and to me this draws all the attention to the ram. … If you notice, there’s no way to put this down if it’s filled with anything, so you best be drinking all night!”

—Christos Orfanos, Class of 2018, economics and classical civilization major, and marketing minor

The Nativity appears in Très riches heures, a 15th-century book of hours created for a French prince, John, Duke of Berry. The lavish manuscript was an extravagant undertaking, painstakingly produced with expensive pigments and gold.

Thanks to the generosity of Bronx dermatologist James Leach, MD, a fine art facsimile of this medieval prayer book—one of the most famous illuminated manuscripts of the 15th century—is housed in Special Collections at Fordham’s Walsh Family Library. It is one of 300 facsimiles, prayer missals, and other objects donated to Fordham by Leach for the benefit of art history students and medieval studies scholars.

The image accompanies the prayer for the office of Prime, the third prayer reading of the day. The Virgin kneels before her son, who lies on a bed of straw, surrounded by angels. God the Father appears at the top of the image, in the semicircular lobe at the top of the frame. He is surrounded by flaming seraphim.

The text reads:

Deus in adiutorium meum intende

Domine ad adiuvandum me festina

Gloria Patri, et Filio: et Spiritui sancto

Translation:

Incline unto my aid O God.

O Lord make haste to help me.

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son: and to the Holy Ghost.

The prayer continues on the following page.

Read more about Fordham’s collection of fine art facsimiles:

Bronx Doctor Donates Medieval Manuscript Facsimiles to Fordham

]]>

Subsequent papal visits were made by Pope John Paul II (seven times) from 1979-99, and Pope Benedict XVI in 2008.

For the month of September, check out the Rose Hill campus Walsh Library’s first-floor display featuring news coverage and photos from the various papal visits.

]]>

Hinkle began at Fordham in 1986 as a shelver, but ultimately spent the majority of his Fordham career as manager of the photocopy and scan center, first in Duane Library and then Walsh Library.

“Bob Hinkle was a particularly beloved member of the library staff,” said Linda LoSchiavo, director of libraries. “A gentle, friendly man, Bob was our resident sage and savant on any number of subjects. His love for Fordham was deep and genuine. We will truly miss this gentleman extraordinaire.”

A wake and funeral Mass will be held Friday, Feb. 27, at Our Lady of Refuge Church (290 East 196th Street, Bronx, NY 10458). Visitation will begin at 10:30 a.m. and Mass will follow at 11:30 a.m.

A reception in the O’Hare Special Collections Room in the Walsh Library will be held following the Mass.

Before coming to Fordham, Hinkle worked at the Firestone Library at Princeton, the Movielab film library in New York City, and the Borough of Manhattan Community College. He received a bachelor’s degree from St. Peter’s College and a master’s degree from Queens College, and had also pursued graduate studies at SUNY Binghamton.

In 2006 he received Fordham University’s 1841 Award, which is given to Fordham staff members who have served the University for 20 years.

“I was on the subway searching for a job when someone flashed a Fordham University book cover,” Hinkle wrote in his award citation regarding his beginnings at the University. “It was a cold day in January of 1986. I had just been laid off as a circulation clerk at the Borough of Manhattan Community College Library… I called the Fordham personnel office and they said come on up. I have been here ever since.”

In addition to his work in the library, Hinkle was an avid painter (he was featured several years ago in an exhibit at The Art Students League in Manhattan) and an aficionado of French language, striped bass fishing, and history. He also had a deep interest in politics—national and international alike—and possessed an almost encyclopedic knowledge of local politics, LoSchiavo said.

“Bob’s greatest impact was in his individual interactions with students and faculty in the library,” she said. “Always ready to help, always eager to discuss whatever subject a student or faculty member was working on, and always cheerful, Bob was considered a friend to decades of library users.”

Cards may be sent to the family via a memorial page created for Robert through Gleason Funeral Home.

]]> The move represents the fruition of two years of planning and collaboration by writing center and library staff, the Department of English, Fordham Facilities Management, John P. Harrington, Ph.D., dean of Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and Michael E. Latham, Ph.D., former dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill.

The move represents the fruition of two years of planning and collaboration by writing center and library staff, the Department of English, Fordham Facilities Management, John P. Harrington, Ph.D., dean of Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and Michael E. Latham, Ph.D., former dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill.

The new space, designed by architect Joel Napach of the Napach Design Group, replaces three former study rooms in the reference area on Walsh’s ground floor. In addition to elegant fixtures that cast perfect reading light, it features spacious work stations and new computers, as well as one free-standing station that can be raised and lowered to accommodate students in wheelchairs.

An expansive conference table and wall-mounted LCD screen will now allow for teleconferencing with off-campus speakers and seminars, as well as real-time collaborations with the Lincoln Center Writing Center.

For Anna Beskin, a doctoral candidate in English and director of the Rose Hill Writing Center (which formerly shared space with the Department of Economics in Dealy Hall), the new location offers greater accessibility and increased visibility.

“It’s a huge sign of support for what we do at the writing center,” she said. “We are a University-wide resource and we can be in a location that is central to the Rose Hill student base where we can be so much more useful to a greater number of students.”

Linda LoSchiavo, director of University Libraries, worked hard to ensure that the center integrated seamlessly into the existing library structure, with matching wood tones, paint colors, and signage. Walsh Library has also dedicated a portion of its entrance lobby as a waiting area for the center’s students.

This physical integration reflects a natural correspondence between the goals of both the writing center and the library. The resources that students need for a wide range of projects—from freshman composition essays to longer research papers, to statements of purpose for graduate school applications—exist just outside the writing center’s doors.

“Once students work with a tutor and realize they have more work to do,” said Beskin, “they can see a reference librarian, ask questions, or search for books; they are already in the right space.”

The writing center’s new home in Walsh Library encourages students to see the interconnections between sound academic writing and information literacy and it helps to foster their skills in both. LoSchiavo said it will go a long way to help foster the Jesuit tradition of developing “perfect eloquence” that is a guiding principle of Fordham’s core curriculum.

“We’ve got a program that’s striving to develop students in their oral and written proficiencies, and now we’ve got the center and the library all under one roof. And to me that’s really a beautiful thing,” she said.

Those interested can sign up for tutoring sessions on the writing center’s website: www.fordhamwc.com

–Nina Heidig

]]>On display are 34 photos of members of the “Harlem Hellfighters,” the first all-black regiment to serve with the American Expeditionary Forces overseas.

The 369th Infantry Regiment, as it was formally named, fought in both world wars and broke ground for African Americans seeking to serve in the U.S. military. The display features photos of the members taken between 1939 and 1945.

During World War I, the regiment was attached to a French army unit because many American soldiers refused to serve with African Americans. By World War II, however, the regiment had been brought under the umbrella of U.S. forces.

During World War I, the regiment was attached to a French army unit because many American soldiers refused to serve with African Americans. By World War II, however, the regiment had been brought under the umbrella of U.S. forces.

The Hellfighters comprised 1,800 men from the five New York City boroughs, with the core group coming from Harlem. Among the more famous Hellfighters were Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, tap dancer and actor; and Regimental Commander Benjamin O. Davis Sr., the first African-American general in the U.S. armed forces.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the unit was sent to guard the Pacific coast and then sent on to Hawaii to help defend against further air attacks.

In Hawaii, many of the servicemen felt more welcomed than in the United States because the native Hawaiian population was itself racially diverse. Outside of their own country, they could see themselves as combat soldiers first, according to an article in The Journal of Social History.

They still faced the residual racist ideas from the mainland, however, the article said. One story circulating on Oahu had the Hawaiian natives trying to be kind to the servicemen by putting pillows on their chairs at a gathering. The natives had been told that black men had tails and figured that sitting on hard chairs would be uncomfortable for them.

By 1944 the first Hawaiian NAACP was established in Honolulu. Following the war, many black servicemen decided to remain on the island.

The somewhat obscure collection came to the attention of Patrice Kane, head of archives and special collections for Fordham Libraries, through a vendor. Kane was able to purchase the collection with the help of Fordham’s Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP).

While the photos capture a critical piece of American history, the soldiers in the photos still remain unidentified; Kane hopes that getting the word out about the collection will change that.

“Somebody’s dad is in these pictures. I would love for their descendants to come forward and identify them,” she said. “They are significant to our history project because they represent a slice of New York City’s African-American history of which very little has been written.”

]]>