An award-winning filmmaker blends horror and sci-fi

When it was time to apply to college, Luke Momo took one tip in particular to heart: Don’t major in film. A close, older friend suggested he pick one of the humanities—English, history, philosophy—and instead explore the ways a particular subject intersects with film.

Now, with an award-winning debut feature under his belt and a trove of ideas to pursue, Momo has been reflecting on his time at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, where he majored in philosophy, dove into filmmaking as a visual arts minor, and forged connections that proved invaluable when it came time to cast his movie, Capsules.

A Princeton, New Jersey, native, Momo was drawn across the river to the University for its “intellectual rigor,” originally choosing to major in classics. He did veer from his friend’s advice a bit by minoring in visual arts with a concentration in film. But a philosophical ethics class he took with professor Janna van Grunsven, Ph.D., during his sophomore year made him reconsider.

“After I took that class, I realized that [it was]what I’d want to do my major in [and explore]the intersection between philosophy and film,” he says. The professor “was able to share with me a higher level of some of the things I was interested in at that time—and I still am. She was very supportive in that way.”

Creating a Cinema Community on Campus

Outside of class, Momo founded Fordham’s Filmmaking Club in 2016, a kind of film study group for students interested in viewing and discussing movies, as well as pursuing projects together.

“We could help each other make our films and collaborate,” he says. “We’d have very memorable screenings of all kinds of different movies that you otherwise wouldn’t see, and you could watch them in a group and discuss them afterward.”

The club continues today, with students collaborating on film projects, sharing them, and hosting film festivals. “It seems to be fulfilling its original purpose and also growing—becoming more and encompassing more ideas and progressing,” Momo says.

He also completed two internships, one at the Film-Makers’ Cooperative—an artist-run nonprofit—and one at Le Cinéma Club, a curated streaming platform featuring one free film each week.

“It was just really cool because week after week, we were researching, writing about, discovering, and highlighting works of film art,” he says, including a number of international films to which he wouldn’t have otherwise been exposed.

From Campus Collaboration to Award-Winning Feature

Capsules, which Momo wrote with Davis Browne, FCLC ’19, features more than half a dozen Fordham graduates in starring and behind-the-scenes roles.

The film blends sci-fi and horror, focusing on four chemistry students who experiment with mysterious substances and find themselves struggling with addiction in an unexpected way: They’ll die unless they take more.

“I just basically pursued an emotional feeling … the fear of letting one’s life slip away and a sadness over mistakes,” says Momo, who directed the film. The premise came after the pandemic, when “we had been through so many traumas personally, in our communities, and on a global level. All these things came together, and the idea for Capsules just sort of emerged.”

The film earned the Best Feature award at the 2022 Philip K. Dick Film Festival in New York City. Momo later sold the film to a distributor, and it’s available to watch on Tubi and Vudu.

Read more “20 in Their 20s” profiles.

]]>“[Ross’s] devil-may-care demeanor, hip Williamsburg filmmaker act could seem like armor. Underneath … was this mushy, soft sweetheart,” said Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock, head of Fordham’s visual arts program at the Lincoln Center campus. “He is the last person who would want to be put on a pedestal. But these characters who come into your life … they become your family, and it’s quite impossible to imagine a world where he’s not padding around [Fordham] in his Chuck Taylors.”

‘The Muse Was Life; the Medium Was Film’

McLaren taught film and media production to Fordham students as an artist in residence. His work, which has been described as “abstract,” “playful,” and “ironic,” has been featured in Fordham’s annual faculty show at the Ildiko Butler Gallery. McLaren often left interpretation of his art up to his viewers. “The kind of artwork I like [is]not nailed down by the artist’s definition,” he once said.

The art that he truly loved, said his colleague Joe Lawton, was experimental non-narrative independent cinematic film.

“He had great knowledge of Walt Disney cartoons, Hollywood films, et cetera, but his real passion was the descriptive and inherent equalities in the idea of film itself,” said Lawton, associate clinical professor of photography. “He was also curious about … life itself. The muse was life; the medium was film.”

Unconventionally Living Cura Personalis

As a faculty member, McLaren wasn’t keen on volunteering for administrative tasks, said Apicella-Hitchcock, but he never hesitated to help out his students.

“I would find him assisting a student one-on-one on how to load Super 8 film into a projector, way beyond his afternoon class. In an odd, quirky way, in his anti-establishment personality way, he embodied cura personalis,” Apicella-Hitchcock said.

McLaren was an “unconventional” professor who encouraged his students to challenge existing norms and think outside the box, said former student Luke Momo, FCLC ’19. He also helped his students improve their craft by pinpointing the deeper meaning behind their self-produced films, said Momo, who noted that’s just what McLaren did when he attended the premiere of Momo’s first feature film, Capsules, at a Manhattan film festival last year.

McLaren gave his students gifts beyond filmmaking, too. “When I was in undergrad, I wasn’t [able to laugh at myself]. I had a lot of pride,” Momo said. “Being more honest and vulnerable…some of those emotions are things that Professor Ross gave me.”

Other former students said McLaren’s vision of the world made them think.

“Ross said once, ‘How strange it is that we sit in dark rooms and watch shadows on the wall to find meaning within ourselves,’” a former student commented on a tribute post. “That always stuck with me.”

A ‘Goofy’ Friend with a Parrot and Two Turtles

McLaren was born on December 4, 1953, in Ontario, Canada. He earned his M.F.A. from Ontario College of Art and taught at many institutions, including Cooper Union and Pratt Institute. His work has been screened at institutions worldwide, including MoMA in New York City and the British Film Institute Southbank in London, and found a permanent home in many art institutions. He received multiple honors, including the Millennium Achievement Award for his contributions to the arts and education. In addition, he founded Funnel Film Theatre in Toronto, an underground film collective active in the 70s and 80s that one writer recently described as “the most important locale for experimental film in Canada.”

He lived in his loft apartment in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where he enjoyed growing plants on the rooftop; spending time with his beloved parrot, Fwankie; and sunbathing with his two turtles, Flotsam and Jetsam, who had the privilege of their own kiddie pool, said Apicella-Hitchcock. He was also a big hockey fan.

From a distance, you might have assumed he was a “goofy wisecracker, a little cynical and sarcastic,” said Apicella-Hitchcock, but at his core, McLaren was a “thoughtful, warm, and loyal friend.”

McLaren is survived by his brother, Gary McLaren, and his sister, Catherine McLaren. A memorial in McLaren’s honor will be held on Feb. 16, 2024, at 6 p.m. at the Lincoln Center campus’s Lipani Gallery, where several of his films will be screened. Contact [email protected] for more information.

by Farida Hughes, FCLC ’91

Several years ago, Baltimore-based abstract artist Farida Hughes began her Blends series of paintings in which she overlaps oil paints and resin to create multilayered works. The colors remain distinct but also form, in any one piece, a rainbow of contrasting and complementing hues created by the bonds among them. Hughes, who earned a B.A. in studio art and English at Fordham and an M.F.A. in painting at the University of Chicago, creates the works as a way to explore her own background as a “uniquely blended individual,” she said—her father immigrated to the U.S. from India, and her mother is of German descent. She also has been collecting stories from friends and acquaintances of their own multicultural backgrounds, and using them to create abstract portraits in which “all the colors together are important,” she said. “Each one has a role to play with the other.”

Hughes’ Blends paintings were recently featured in an exhibition, “A Line Doesn’t End with Me,” at the Athenaeum in Alexandria, Virginia.

Sleep with Me

created and hosted by Drew Ackerman, FCRH ’96

For most podcasters, putting listeners to sleep would be considered a failure. For Drew Ackerman, it’s the whole point. Ackerman started this popular, twice-weekly podcast in 2003, inspired by his own struggles with insomnia and the late-night comedy radio shows he listened to as a child to help himself doze off. With a stated goal to “help grownups fall asleep in the deep, dark night,” each episode is a stream-of-consciousness exercise in distracted storytelling, with Ackerman’s deep, monotonous voice guiding listeners through a “bedtime story” filled with one less-than-thrilling tangent after another, all in an effort to bore—and comfort—people into slumber. Sleep with Me averages more than 3 million listeners a month and has more than 6,000 supporters on Patreon—a level of success that has allowed Ackerman, who had long balanced the podcast with a job as a librarian, to devote himself to the show full time. And he has attracted the attention of The New York Times, which recently described the podcast as “close to a sleeping pill in audio form.” With the same self-deprecating spirit that imbues Sleep with Me, Ackerman, who refers to himself as “Scooter” on the show, recently told The Sydney Morning Herald, “I’m naturally boring, so I think that helps.”

—Adam Kaufman

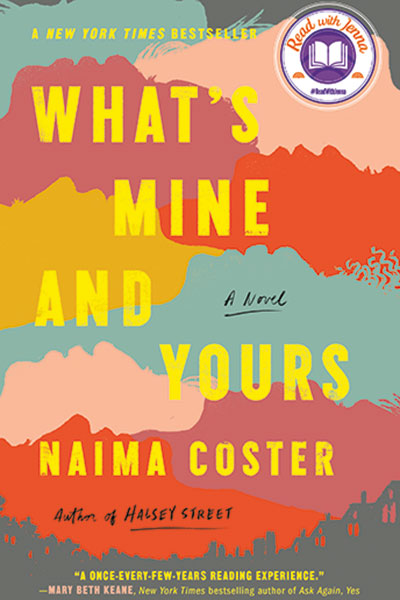

What’s Mine and Yours

by Naima Coster, GSAS ’12

Soon after it was published in March, Naima Coster’s second novel became a New York Times bestseller. It’s an emotionally complex, resonant story of the integration of a North Carolina public high school—and the lasting consequences it has on two families. The narrative shifts back and forth in time, from the early 1990s to 2020. At the heart of it are Gee, a Black teenager whose mother, Jade, fights to get him into the predominantly white high school on the west side of town, and Noelle, a white-presenting Latina whose mother leads an effort to keep the new students out. Each family fights to overcome poverty and trauma—when Gee was 6, he saw his mother’s boyfriend, Ray, shot and killed; Noelle’s father, Robby, spends most of her and her sisters’ childhood in jail or absent due to drug addiction. But when they participate in a school production of Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, Gee and Noelle fall in love, drawing their families together in ways big and small for years to come. It’s an affecting coming-of-age story, highlighting how race and racism, love and loss shape the characters’ lives.

Soon after it was published in March, Naima Coster’s second novel became a New York Times bestseller. It’s an emotionally complex, resonant story of the integration of a North Carolina public high school—and the lasting consequences it has on two families. The narrative shifts back and forth in time, from the early 1990s to 2020. At the heart of it are Gee, a Black teenager whose mother, Jade, fights to get him into the predominantly white high school on the west side of town, and Noelle, a white-presenting Latina whose mother leads an effort to keep the new students out. Each family fights to overcome poverty and trauma—when Gee was 6, he saw his mother’s boyfriend, Ray, shot and killed; Noelle’s father, Robby, spends most of her and her sisters’ childhood in jail or absent due to drug addiction. But when they participate in a school production of Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, Gee and Noelle fall in love, drawing their families together in ways big and small for years to come. It’s an affecting coming-of-age story, highlighting how race and racism, love and loss shape the characters’ lives.

—Ryan Stellabotte

“I wanted to bridge the gap between all the urban life and energy outside the doors of the University and have students go out into the world and reflect on where they are in a larger context,” said Mark Street, associate professor of visual arts, who collaborated with Fordham’s Center for Community Engaged Learning for the class. “The idea was to get them going out as observers, as interactors, and as partners to the community.”

The students’ observations bloomed into works of art—photos, videos, paintings, songs, drawings, and posters—and culminated in an online gallery show.

Students first met neighborhood activists and artists over Zoom, from whom they learned about local challenges facing their community, including homelessness, food insecurity, and gentrification. Those discussions were supplemented by readings, videos, and in-class conversations, including a discussion about how a neighborhood can change without abandoning its less wealthy residents.

Then the students donned masks and explored Hell’s Kitchen with their classmates. Students fanned out across the West Side and recorded city life on their smartphones. In one excursion, they coincidentally met Gwyneth Leech, a local artist who became an impromptu class guest speaker over Zoom. During individual trips, students engaged with community organizations through activities like creating masks for New York City residents, coordinating a sock drive for the homeless, and growing produce for a local food pantry, said Street.

Most of their classes took place virtually, but when they gathered in person, they tried to make them as safe as possible.

“We were recalling the day’s image gathering and shouting six feet apart over the roar of the fountain [at Lincoln Center],” Street said, recalling one of their outdoor classes. “You do the best you can in the pandemic.”

Leeza Richter, a communications and visual arts double major, was inspired to photograph a local rooftop farm after a class discussion with guest speaker Tiffany Triplett Henkel, a pastor and community leader who spoke about the Hell’s Kitchen Farm Project. Richter not only documented the rooftop farm through photos and video, but also helped volunteer farmers care for their crops, which are donated to a food pantry.

“I was really interested in this idea of food being grown here for people here and what that means about the community and everyone who’s a part of this rooftop project,” Richter said. “It was really rewarding to step outside of my own familiarity in Hell’s Kitchen and be able to look at this space that I’m sharing with so many people who have been here much longer than I have, and what this physical plot of land means to them and how they’ve expanded it.”

Many students documented life in Hell’s Kitchen, but some dove into their own neighborhoods. Jazmin Ali captured Caribbean culture in her native Prospect Lefferts Gardens neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York, through intimate portraits of her neighbors and their businesses.

Valeria Deminova, a student athlete from Russia, recorded scenes in Hell’s Kitchen on camera and then used acrylic paints to recreate moments that had caught her eye, including a homeless man asking for money in a restaurant and a masked policeman on a horse. In another painting, “Familial Bond,” she captured a father walking with his daughters down a street.

“When I saw this frame in one of my videos, I felt a lot of warmth and could feel the father’s care for his daughters,” Deminova wrote in a photo caption. “He carried one of his daughters on his shoulders and carefully held the other with his hand.” After giving her artwork to local community members, she returned to her native Moscow for winter break, where she plans to create a similar project, said Professor Street.

Evelina Tokareva, a psychology major and visual arts minor who is also originally from Russia, said she has lived on the Upper West Side since age 10. But her class project helped her see Hell’s Kitchen in a new light. After recording several walks through her neighborhood, Tokareva said she became more attuned to things around her, from strangers’ conversations to the ways that local businesses are being affected by gentrification and the pandemic.

“A lot more places are getting shut down, and it just makes me think, what’s to come after?” said Tokareva, who currently volunteers at Goddard Riverside and works with Socks in the City to distribute clothes to the homeless. “I walked out of this class learning and feeling so much more for my neighborhood.”

Hughes, who earned a B.A. in studio art and English at Fordham College at Lincoln Center and an M.F.A. in painting at the University of Chicago, exhibits her work frequently, including at the recent I Contain Multitudes show at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design. That exhibition invited viewers to “consider how multiculturalism impacts their lives, and how it relates to the issues of immigration and diversity in today’s society.”

She spoke with FORDHAM magazine about her own background, her artistic process, and how people’s stories inform her work.

In a statement about your work, you wrote about the idea of blending in terms of your own multicultural background. What is that background, exactly?

My father is an immigrant from India. My mother is German, but she was born here. So, German Indian.

An American family.

An American family. Two religions. I’ve always felt that I’ve had that duality in my world, and I kind of straddled both religions, the cultural differences. But also my mother grew up on a farm, my father grew up in the city. I currently live in a more pastoral setting, but I have my studio in the city. And I think I gain energy from both of those environments, and I like to bridge them.

How does your own sense of multiculturalism inform what comes out in your work?

I think it’s probably the heart of my work. It’s become the heart of my subject matter dealing with relationships between people, and how we get along, and how we form community, and how we understand each other. My Common Threads series is really about that, using the threads as a natural metaphor for shared experiences as we discuss things and start to unfold who we are and where we’re from, and find those links.

Picasso used to joke that it took him four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to learn to paint like a child. Have you always created abstract pieces, or has that developed over time?

I always knew I was an abstract painter at heart. I can show you my very first oil painting, done at 16. But I always struggled with subject matter, what I was going to paint. And, to me, my abstraction has to come from a story. It comes from a place or an experience that I’ve observed, or a story I’ve heard, or somebody I know. So, I never feel good about a work that I’ve done if it’s purely moving color and shape around. It needs to have a place to come from, an origin.

For better or for worse, in America multiculturalism is often defined by color. Your work is all about the interplay of color. Is this metaphor intended?

In my Blends series, it is intentional. The paintings to me are portraits, but they’re simple until you look closer and you see that there are a lot of layers of color. But the color is very important, because they’re blended together in a way that creates, for me, a new beautiful shape. So, all the colors together are important. Each one has a role to play with the other.

When you say they’re portraits, what does that mean?

That, again, goes to that multiculturalism question. I’ve been, for three years now, collecting stories from friends and acquaintances of their cultural and ethnic backgrounds and compiling them in a book. Those stories, of family experiences or things that would be important to an individual in their family’s cultural background, are very important to the paintings. The paintings, then, are a composite portrait of many people, because they’re blended together, blended histories.

So, tell me a little bit about the story behind this painting [Blend 23md] and how it went from being his or her or their story to becoming that visual abstract portrait you created.

I’m going to read you the story, but I’m going to take out names because I always tell the people sharing the stories that they’ll be anonymous.

I’m half Mexican and half Irish. I lived in Mexico as a kid and moved here for first grade. I was back in Mexico over winter break, and I ran into a woman who had not seen me since I was 5 years old. She watched me speaking with my daughter and wife in English and blinked at me with amazement, saying, “The last time I saw you, you didn’t even know how to speak English.” It was a powerful reminder of how my life has changed since moving here. My daughter is a quarter Mexican, quarter Polish, quarter Irish, and quarter Scottish. When we landed in Minnesota after being away, she saw her breath from the cold and said, “This is what home should look like.” We are having very different childhoods.

That’s an example of the stories that I collect, and I like to exhibit the stories with the paintings.

So then how does that story, which is a lovely and charming and American story, actually become that visual representation?

I might choose a color that the story evokes for me at the moment and then build off that color, playing with complements, usually. Most of the time, I know the person who has written the story. I might know their profile or the way they walk or the way they sit, so shapes kind of get dictated by that. And then I start to play with how those different shapes interact with each other on the panel.

But the shapes are not necessarily representative of the story part for part. I don’t think I need to be that literal, because in the end it’s an abstract portrait and it’s open to interpretation. I think colors portray emotion, colors and shapes have presence, and the interaction is important. Some of the stories have tension, some of them have anger, some of them have sorrow. I don’t necessarily want to portray those things; I really want to create a collection of new images.

You make your pieces with resin, which is unusual. What is your process?

I always start out with one color. The medium I’m working with starts to cure in 45 minutes, it starts to set up, so I have a very quick open time with it. I have to know what I’m doing to control the shapes. It’s still moving when I leave, but the shape that I make is really important to me. Then I let it cure before I do the next color. So I build them up in a series from the back to the top.

Baltimore has a complicated multicultural history. Do you think that that’s likely to, over the course of the years, create an evolution in your work?

I have lived here for a year now, and as an artist, you’re always a little isolated from the place you exist in, because you’re working in your studio. At the same time, I get energy from the place I live in, so I like coming into the city, I like seeing what’s going on, seeing certain people on the street, on the corners every day. It’s just that sort of dynamic place that I enjoy and like to observe, but, as opposed to any other place I’ve lived, I feel like it’s taking a long time and will take longer to understand the city, and I don’t want to make any assumptions.

It’s complicated, and complex.

I wanted to be here. The building itself is cobbled together—it’s old, some of the walls are new, but it’s repaired, you can see things that are screwed down. I painted the floor when I moved in because I needed that sense of serenity, I guess, because my work is complicated, but, as you can see, there are exposed brick walls with remnants of work that’s been done here. I enjoy that; I think that’s important to a place. I like seeing other people’s notes to each other on the wall. Things were made here, which is great to me. I think that Baltimore is a city of people who reinvent themselves, at least in this neighborhood. There’s a creative force, a do-it-yourself mentality here that is vibrant and alive.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by B.A. Van Sise, FCLC ’05.

Hughes’ artwork will be featured in “Layers of Existence,” an exhibition at Walker Fine Art in Denver from Nov. 8, 2019, through Jan. 4, 2020.

]]>Although the collages are striking, the sites themselves seem unremarkable: A hair salon, a burger joint, street corners, churches, and other locales bear little to no trace of their fraught past. Some of the titles, however, underscore Ruble’s concern with the “ways we remember—and forget—the charged events of our country’s turbulent history of race relations,” she writes. A Jersey City sidewalk scene, for instance, is called Everyone here is aware of what has happened but they also want to forget as quickly as possible.

Ruble, who has taught in Fordham’s visual arts department since 2001, created the collages over the past few years. She first showed them last fall at the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey and again this past winter at the Foley Gallery on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. She spoke with FORDHAM magazine via email in April.

As you researched these sites, did you learn anything that surprised you or ran counter to your sense of New Jersey’s place in U.S. history?

Oh my gosh, yes! I’d always known that the North’s relationship to slavery was a complicated one, but one thing that really surprised me was that New Jersey was known as the “slave state of the North.” In 1846, it enacted an abolition law that freed all black children born after its passage but designated the state’s remaining slaves as “apprentices for life.” Eighteen of these “apprentices” still remained in 1860, making New Jersey the last Northern state to enslave people. I was also surprised by just how few white Northerners supported the Underground Railroad.

Did you have a hard time finding and getting access to safe-house locations?

It’s ironic—in its day, the Underground Railroad was a highly unpopular movement among Northern whites, and also highly illegal, of course. Participants had to operate in secrecy. Today, on the other hand, it’s held up as evidence of our country’s inherent morality, and everyone with a trap door or passageway in the basement likes to speculate that their home was part of the effort to help fugitives escape. I didn’t have a hard time finding or getting access to the safe-house locations—what was harder was actually confirming that they were genuine.

Which riot locations did you depict in the series?

The state had five major race riots—in Jersey City, Paterson, Newark, Plainfield, and Asbury Park. They all happened in the 1960s, except for Asbury Park, which took place on Independence Day, 1970. When I first began this series, I’d planned to depict the place where the riots “started.” But that quickly grew complicated as I got further into my research. Was the “start” of the riot the street corner where the first brick or Molotov cocktail was thrown? Or was it where the precipitating event occurred—for instance, where the Newark police arrested and brutally beat a black cab driver who’d done nothing more than pass a double-parked squad car? Identifying where something supposedly began is freighted with judgments about guilt and responsibility. Looking at the longer arc of history, you can easily make the case that all of the riots actually began with the original violence of slavery—there’s a direct line from slavery to Jim Crow to the uprisings of the civil rights era, which were a response to centuries of horrific brutality.

Tell me about Everyone here is aware of what has happened but they also want to forget as quickly as possible. Why did you choose that title for the piece?

All of the pieces that depict riot sites are titled with sentences taken from contemporaneous newspaper reports of the incidents. That particular sentence struck me not only as having an obvious connection to the feelings of the time but also as symbolizing how many have come to view the uprisings of the 1960s, 50 years later—as shameful events better left out of the history books because they threaten the dominant narrative of our country as a land of opportunity and freedom.

Why are the safe-house locations called Untitled with the name of the town in parentheses?

I left the Underground Railroad sites untitled to allude to the secrecy that shrouded them in their day. I thought a lot about the idea of silence while making this series, and how silence has many different connotations. In the context of the Underground Railroad, silence was used as a tool of protection. But there’s also silence—or more accurately, silencing—that occurs in the context of oppression. Martin Luther King referred to the riots of the civil rights era as “the language of the unheard.” And finally there’s the silence of the landscape itself, which swallows the secrets of its past with every big-box store and parking lot that’s laid down on historically significant ground.

You took the title of your series from the 1965 Flannery O’Connor short story “Everything That Rises Must Converge.” Why did you use those words to unite the collages you created?

These places, both the Underground Railroad sites and the race riot sites, were about rising—rising up, rising against—and about convergence, in both cooperation and conflict. [O’Connor’s story is] about an altercation between a white woman and black woman riding a bus in the South shortly after the desegregation of the transportation system. The fact that the story is about race relations—and about the complicated relationship between forward and backward movement—just underscored the fact that it was the right title for my series.

The title isn’t original to O’Connor. She took it from the Jesuit scientist and philosopher Teilhard de Chardin, who wrote about spiritual evolution. Do you feel you’ve transformed the title in some way with your work?

I haven’t studied Teilhard in as much depth as I’d like to, but my understanding is that he believed that creation was not a singular event but rather an ongoing development—that evolution was a spiritual and moral progression toward a point associated with Christ. I think O’Connor recognized that we are only partway through that progression toward convergence with Christ, and I think her story is about the messiness of that trajectory. My adopting of her title 50 years later is not so much a transformation of its meaning as it is an accounting of our progress. How much closer are we to Teilhard’s convergence? Perhaps not as close as we should be. But I don’t see this strictly as a condemning fact. I see it as a call to rise to everything we as a nation have claimed to believe in. As a call to keep struggling toward grace.

You’ve written that the collages depict a “present that’s unmoored from its past but never perfectly free from it.” Is that a good thing? Should we be free from the past? Or have you tried to bring about a kind of artistic convergence of past and present?

I’m tempted to say, yes, that’s exactly what I’m trying to do. But actually I think the collages do just the opposite—they talk about our disconnect from the past. Or maybe they do both. In the course of making this series, I’ve thought a lot about remembering and forgetting, and when each is “better.” Let’s for a second assume that the entire nation could completely forget our history. That we all woke up tomorrow with amnesia. We would presumably recognize difference in skin tone, but what would we make of it? It would be an interesting experiment—maybe we’d all get along better, maybe not.

As a white woman, I’ve also thought a lot about the implications of looking so closely at white-initiated violence against black communities and individuals. Does this focus just ossify modes of oppression and perception that still exist? Does it suppress stories about black achievement and triumph? Or is it a critically needed acknowledgment of the white community’s wrongdoing? An attempt to take responsibility for the past and move forward, in whatever way that may mean?

Has the Black Lives Matter movement influenced your work or your thinking about this project?

I started this series a year before the events in Ferguson, well before the Black Lives Matter movement. Although I came to the series through my earlier interest in conflict in general, the project obviously immediately became one about past and contemporary race relations. It was a subject that wasn’t dominating the national conversation in the same way it is now, and the series was my own small attempt to open up that conversation. The Black Lives Matter movement has moved the conversation forward in much more effective, widespread ways, of course. Last year I participated in a march in New York City for Eric Garner. Along with about a hundred other people, I laid down in a street near Penn Station. After two years of visiting past riot sites on my own, in a very solitary way, it was an incredibly moving experience to be among hundreds with a collective voice strong enough to bring the city to a screeching halt. It felt like stopping the heart of the city and pushing the blood in a new direction, toward extremities that hadn’t been receiving enough of it.

New York Times art critic Ken Johnson described your collages as being “deadpan cool” but conceptually “loaded” and “painfully hot.” Is that hot and cool combo something you wanted to convey?

Definitely. Conceptually, this is a very loaded topic to address. And I’m an artist, not a scholar, on these subjects—it’s not my place to offer any kind of “authoritative” statement. The only way I personally feel comfortable addressing race relations is by looking in a very objective, “deadpan cool” way at how these sites of historical significance have changed over the years. What gets lost? What gets remembered? To what end? The answers to these questions help give us a sense of where we are today and what we need to work toward.

What would you like viewers to take away from the project?

I’d love for viewers to come away from it looking more closely at everything that surrounds them—being curious about hidden narratives. Areas that are economically depressed are rendered anonymous—or worse, as “dangerous” or “blighted.” Disconnecting communities from their history in this way is a powerful means of perpetuating their oppression. Regardless of where you live, that place has a history. Maybe a Walmart sits on it. Maybe it’s just an empty lot. The present often obliterates the past. But knowing the past may give you a sense of agency you might not have had otherwise.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Ryan Stellabotte.

]]>The team of Inside Out, a project by the artist JR, parked a customized box truck and photo booth on West 60th Street. Project volunteers asked passersby if they wanted to have their picture taken for a larger-than-life photo that would be posted on the wall.

The project attracted a medley of characters: Residents of nearby buildings, members of the Fordham community, and teens walking from their school on Amsterdam Avenue to the nearby subway station lined up to be photographed.

Technical issues forced the team to print the portraits at its SoHo studio (and not in the truck, as planned), leading to a lag during which they were only able to take pictures. But once they began wheat-pasting photos to the wall, the event, which has taken place in cities internationally, began to take shape. The crew hung 28 portraits before rain forced them to return several days later to paste the rest of the approximately 100 portraits that were taken.

[doptg id=”8″]

Photos by Ryan Brenizer

Inside Out is the creation of JR, a former graffiti artist from Paris who became famous for pasting images of human faces on massive canvasses around the world. He was awarded the 2011 TED Prize, which came with $100,000, a prize meant to fund the winner’s “wish to change the world.”

That wish, he said in his acceptance speech, was to “stand up for what you care about by participating in a global art project, and together we’ll turn the world inside out.” He said art is not supposed to change the world in practical ways, but to change perceptions. “What we see changes who we are. When we act together, the whole thing is much more than the sum of the parts.”

The project was brought to Fordham by the University’s urban studies program’s distinguished visitor series. The series is funded by a grant from the law firm Podell, Schwartz, Schechter & Banfield, of which Fordham alumnus Bill Banfield, FCRH ’74, is a partner.

JR was invited to be this year’s distinguished visitor, as part of the program’s focus this year on urban arts. Other events have included a visit by filmmaker Andrew Padilla and a screening of his film El Barrio Tours, and a conference on “Law, Space, and Artistic Expression.”

Mark Street, assistant professor of visual arts at Fordham, said he first encountered Inside Out in 2013, when the crew photographed 6,000 people over three weeks in Times Square. Photos have also been posted in North Dakota, Tunisia, the South Bronx, Tanzania, and the North Pole. He liked the project’s simplicity and accessibility to the public, so he approached the group on behalf of Fordham.

“This project takes street photography and makes it personal by taking literally anyone’s photograph and putting it on the wall,” he said. He also liked he fact that the project was open to those outside of the Fordham community because although Fordham is a private university, it shares a lot of space with the general public.

“The idea of Inside Out is to play with that liminal space of the public and the private a little bit,” he said. “At its best, this wall will be an amalgam of whoever happens to wander by.”

One random passerby was Jacqueline Gonzalez, who was walking with her 4-year-old daughter Mia back to their apartment. Mia, who proudly showed off her “funny face” for volunteers, had her picture taken. Mom was camera shy, but she loved the project.

“It’s really busy around here, and I don’t really stop that much. But now that there’s art here, maybe I’ll stop more often,” she said.

For Rosemary Wakeman, PhD, director of the Urban Studies program, JR’s focus on spontaneous public involvement made him especially attractive.

“JR’s project highlights urban art and public space and the ways in which the city acts as a collective canvas,” she said.

Victoria Monaco, a Fordham College Lincoln Center junior, found out about the project that morning and came by. She said street art is integral to New York City.

“I very much consider myself a part of the city, so to have my image physically be a part of the city as well, even if it is for a short period of time, is really cool,” she said.

Vincent DeCola, SJ, assistant dean of students at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, made sure Fordham administrators were represented on the wall. He counts himself a fan of public art, something he said the wall on West 60th Street sorely needed.

“Personally, I don’t like walking down a street with a big cement wall. I’ll often go down another block where there are stores or activities,” he said. “Its great to bring some life, and it’s sort of like the face of Fordham.”

—Patrick Verel is the assistant editor of Inside Fordham.

Watch a video of the project.

]]>

Like many children of immigrants in New York City, Katte Geneta, FCLC ’06, grew up with her head in two worlds.

“Both of my parents were born in the Philippines, and they’ve been bringing me and my sister back since we were kids,” she says. “I’ve always felt a sense of wonder when I go.”

Geneta recalls one of her first plane trips to her ancestral homeland, when she was about 4 years old.

“I was looking out over the Philippines, looking at the vast ocean, the water,” she says, “and I couldn’t tell if I was seeing islands or clouds.”

That impressionistic memory has inspired her recent work, the Cosmos Series, which was shown in New York City in September at the 7th Annual Governors Island Art Fair. (The artist-run show closed Sept. 28.)

Using a mix of natural materials, including volcanic ash and lahar, a hardened slurry of volcanic sludge that she grinds down, Geneta has created a series of “drawings from dust.” On her website she notes that she deliberately leaves the images in “an obscured state, somewhere between reality and memory.”

The ash and lahar Geneta uses come from the Philippines, from an aunt who lives in Quezon City, about 90 miles southeast of Mount Pinatubo. Twenty-three years ago, on June 15, 1991, Pinatubo exploded in what the U.S. Geological Survey has described as the second-largest volcanic eruption on Earth in the 20th century.

Geneta says using the volcanic materials in her art helps her get in touch with her Philippine heritage while conveying a sense of the beauty and destructive power of nature—and of the fragility of life.

“I wanted to use something that originated where my family originated,” she says. “And I felt ash would be perfect. I use chalk, volcanic ash, charcoal, things that crumble because they’re so delicate. That delicacy is what I wanted to carry over to the viewer.

“With dust,” she adds, “it’s related in a biblical sense, that we’re made of dust. I really like that.”

Casey Ruble, artist in residence at Fordham, is one of Geneta’s former professors. She says Geneta’s work has matured a great deal since her undergraduate days at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, where she earned a degree in visual art with a minor in philosophy. “But even then it was marked by a certain quietude, subtlety, and attention to the nuances of light, all of which come through strongly in the work she’s making today.”

Ruble adds: “Katte’s inclusion of volcanic dust as a medium … gives an edge to the more dreamy, soft-focus imagery, and also nods to the land art movement of the 1960s and ’70s.”

Geneta says she’s particularly influenced by water. She and her husband lived in Piermont, N.Y., before settling in the Inwood section of Manhattan. “Living next to the Hudson River,” she says, “has been a big thing for my work.”

In November, however, she’s opting for a temporary change of scenery. She’ll be taking part in the visiting artists and scholars program at the American Academy in Rome.

“I’ve never been to Europe, so I can’t imagine what it’s going to be like,” she says. “I’ll be there to absorb a new place and let it influence my work.”

]]>

Photo by Gerald Foster

The world is a complex place. William Conlon believes his art should reflect that.

Conlon, a professor of visual arts since 1979 and the director of the visual arts program until 2005, strives in his work to show how abstraction can show aspects of the world we live in that cannot be shown through realism or traditional, realistic paintings. Instead of words, shapes and forms are the language of his work.

“I am trying to construct some things that, when you look at them, you begin to see a very complex interactive space where you’re not really sure what’s happening, where things are changing in front of you and you’re not really sure why,” he said.

They’re not illusions, though. Conlon prefers to think of them as works that “flip and flop on you.”

A classic everyday example of this flip-flop phenomenon is the FedEx logo. People who are purely verbal, Conlon says, do not see the subtlety of the logo, which contains a beautiful arrow between the lettering. In perceptual psychology, this is called a subjective contour.

“When you see it, you’ll never forget it, and it’s something I use to play a game with my students. The arrow is there, but it’s subconscious. Just like in my work, you don’t see it, but its there.”

For over 40 years, from his studios in New York’s SoHo and in Maine, Conlon has crafted several series of works, from Einstein’s Waltzes to the Great Diamond series, the latter named for the island where his Maine studio is located. His paintings have been exhibited in major galleries and museums throughout the United States and Europe.

He’s currently working on the Collider series, which he started three years ago. Each piece takes three to four months to complete, and is first laid out as an 8.5-by 11-inch pencil sketch before being blown up to a larger scale, where he adds colors.

Conlon will be taking a sabbatical in Italy in January to study the master painters. In the meantime, he’s teaching drawing and collage at Lincoln Center and painting at Rose Hill. Teaching, he said, informs his own work, such as when he discusses with students the concept of visual metaphor—something that explains a construct or an idea visually.

“We got to talking about the environment in a class recently, and how this country is stagnant in its ability to deal with global warming and efficient energy,” he said. He then asked the class what would be a good visual analogy for the concept, that would make sense to the greater public.

The answer students came up with was the idea of the Statue of Liberty holding up a modern windmill instead of a torch.

Teaching art as part of a liberal arts curriculum to a student population that increasingly hails from outside the United States provides challenges that Conlon relishes. Trying to explain the significance of Andy Warhol and the Pop Art movement to a student from Beijing, for instance, is tough. One student from China who struggled with art history comes to mind.

“I said, ‘Where would you go if you wanted to learn about fish? You go to a fish market, look at the fish, and ask them, ‘what’s that fish, what’s this fish?’ ‘That’s a lobster, that’s this, that’s that.’ You’ve got to go to a museum and start walking around on your own.’ This kid has had an epiphany, because she’s walked into the museum on her own terms, and she’s had to deal with what she’s looking at,” he said.

“That, to me, is what great teaching is about. It’s not about anything creative I do personally; I’ve just helped a kid learn on their own.”

Conlon is proud that—some 33 years after coming to Fordham, when the department consisted of him and a few adjuncts—the visual arts curriculum is firmly established here. There are now 11 full time faculty members, eight adjuncts, and several work and display spaces at both the Rose Hill and Lincoln Center campuses. The number of student fine arts majors is approximately 100 annually.

“We have kids who have graduated in the last 10 years who are working in Williamsburg and struggling, and not going down to Wall Street,” he said. “They’re trying to make art. I’m excited about that.”

The Fordham University Women’s Choir conducted by Stephen Fox and the Fordham University Choir conducted by Robert Minotti performed Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms, Mark Jennings’ O Crux and Gabriel Fauré’s Cantique de Jean Racine and Requiem. The Bronx Arts Ensemble provided the music.

Gregory Waldrop, S.J., assistant professor of art history, discussed the mural The Crucifixion on April 9 at the Church of St. Paul the Apostle. The mural, which was painted by William Laurel Harris from 1906 to 1908, hangs above the door of the church.

The story depicted in the artwork is very familiar and has a “classic cast,” as Father Waldrop called it, featuring Jesus surrounded by golden ether, the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene and St. John.

The crucifix in the mural is in axis with the cross over the altar at the front of the church.

“The conjunction of images of Christ’s saving body defines a space, and gathers up in that space all those present in the church—the flock, who gather to praise God on the cross, who gather to hear the word proclaimed from the pulpit, who gather to receive Eucharist at the altar,” Father Waldrop said.

Father Waldrop discussed details that only can be seen by looking closely at the mural from the balcony. He described the gold shimmer that coats the pink sky and purple city in the artwork. He said that the city scene and sunset are based on the actual Jerusalem, at least in mood and lighting, and show a definite moment in time.

The city painted in the mural above the entrance of church is contrasted with New York, the “very real, very alive, very specific city where hope is made concrete in our living out the love that God has shown us,” he said.

Monsignor Joseph G. Quinn, vice president for University mission and ministry, spoke on April 10 about the Stations of the Cross at the Fordham University Church.

Photos by Michael Dames.

-Jenny Hirsch

The Fordham College at Lincoln Center community participated in Park(ing) Day NYC on Sept. 17. Park(ing) Day is an international event in which parking spots are reclaimed and turned into people-friendly spaces for one day.

Fordham students from the theater, architecture and urban studies departments collaborated to design a public park and outdoor theater in two parking spaces on the corner of Columbus Avenue and W 60th Street.

The set, made of cardboard, was built by Colin Cathcart’s Architecture class. Students from Matthew Maguire’s acting class performed a bit of Shakespeare in the park(ing) space.

—Gina Vergel