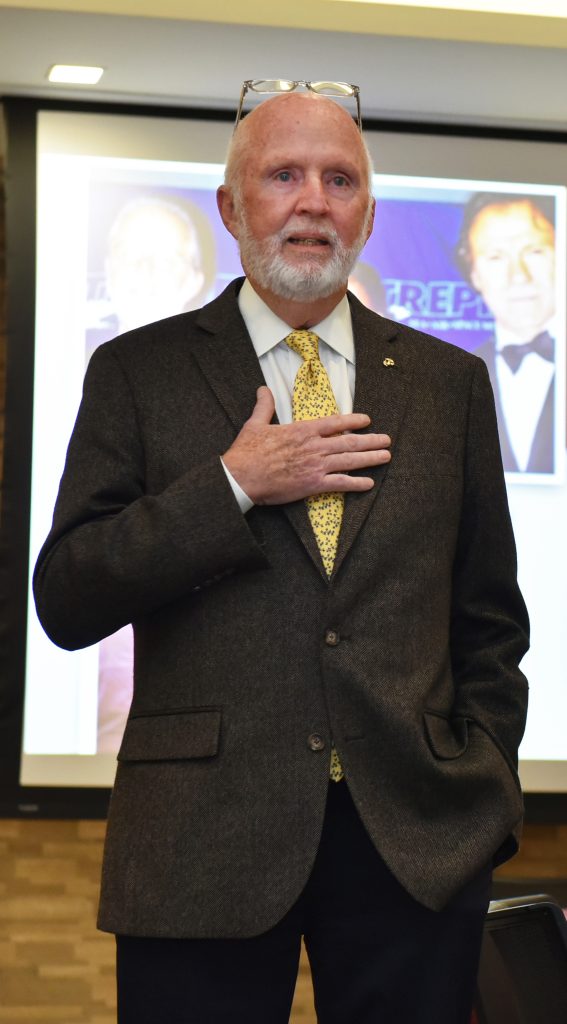

“Since the Civil War, Fordham’s men and women have distinguished themselves with courage and honor on America’s battlefields—wherever it has taken them,” he said on Saturday at Fordham’s inaugural military ball, celebrating 175 years of military training and service at the University. “My family, as well as many of yours, has courageously stepped forward when our country called them.”

Gregory was inducted into the Fordham University Military Hall of Fame at the dinner, which was held at the University’s Lincoln Center campus.

“Warren exemplifies cura personalis,” or care for the whole person, said Matthew Butler, PCS ’16, senior director of the University’s Office of Military and Veterans’ Services, referencing one of the tenets of a Fordham, Jesuit education—the promise to encourage and support students, mind, body, heart, and soul. Butler, who graduated from Fordham in 2016 after serving in the Marines, said he counts himself among the Fordham student veterans Gregory has mentored.

From Military Service to Social Work

During the Vietnam War, Gregory served in Chau Doc Province, and he received a Vietnam Air Combat Medal, a Bronze Star, and a Vietnam Service Ribbon for his actions. After he was discharged, he worked in politics and finance in Washington, D.C., before he felt a familiar pull toward service, albeit of a different kind.

He joined Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA), a national organization that works with state court systems to offer counseling and support to children in foster care. He went on to earn a master’s degree in social work and become a licensed master social worker, putting his new skills to use in the Army once again, at Fort Cavazos and Fort Hood, where he helped service members returning from combat deployments and worked on suicide prevention and other programs “that made an impact on the lives of his soldiers,” Butler said.

Before retiring, Gregory returned to CASA, first in California and then in Westchester County, New York. He now lives in Utah, and he continues to work with veterans—including at Fordham, where his influence helped lead to the creation of an art history and appreciation course for veterans. The course is open to students in the School of Professional and Continuing Studies and is held at the Lincoln Center campus.

His support isn’t limited to veterans, though. In 1991, Gregory and other members of the Class of 1966 established an endowed scholarship to honor George McMahon, S.J., a former dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill who drove home the value of service, calling it “the rent we pay for our time on Earth.”

“We have to believe in the totality of ourselves, and that’s, I think, what my Fordham education gave me,” Gregory said. “We are part of the universe; we are part of a lot of different things. Military service is an important part of that. My memories of Vietnam are a part of that mix, but there’s also another part: There’s the humanity of life, the opening of understanding, the ability to listen.”

In addition to Gregory, Stephanie Ramos-Tomeoni, a 2005 alumna of Fordham’s Army ROTC program who is now a correspondent for ABC News and a major in the U.S. Army Reserves, was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

The military ball was held to help underwrite academic, social, and career transition programming for student veterans, ROTC cadets and midshipmen, and other military-connected students at Fordham.

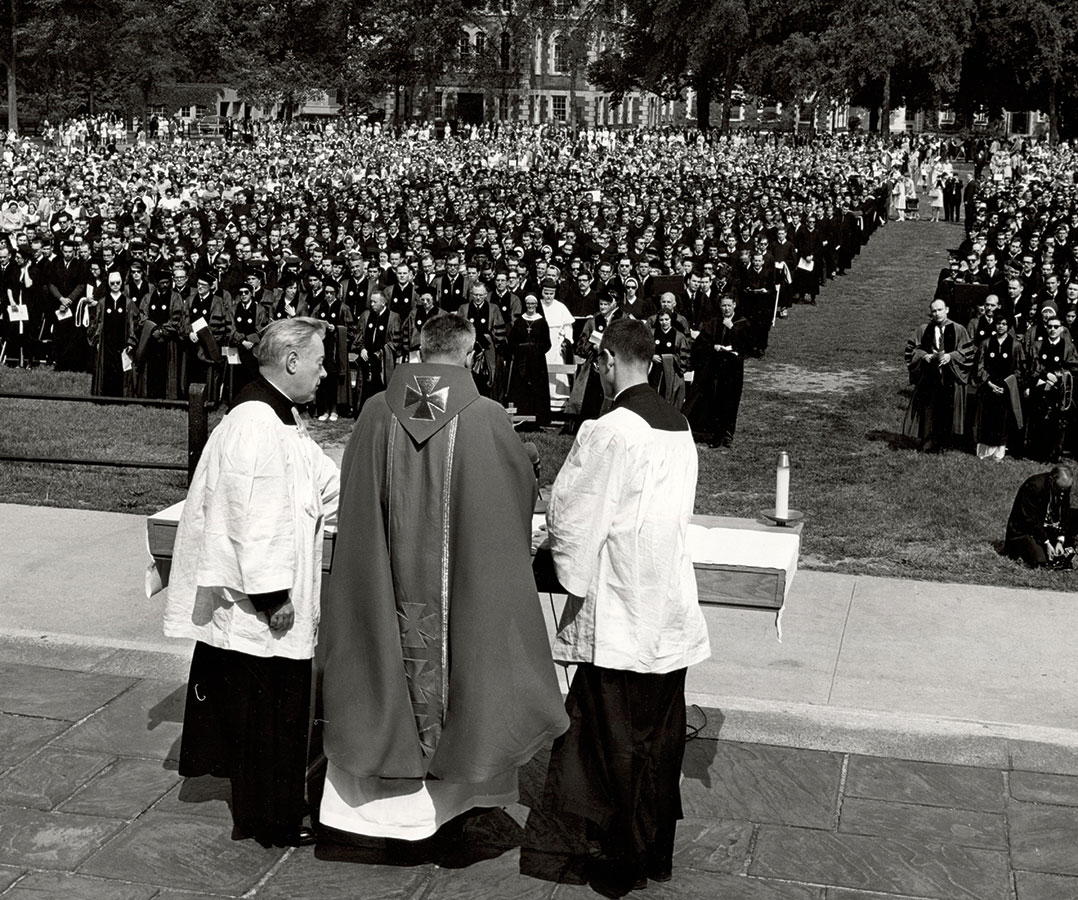

]]>Tradition holds that Fordham’s military heritage dates from 1848, when the state of New York issued Fordham 12 muskets for defense against the threat of nativist rioters, noted Lt. Col. Paul Tanghe, Ph.D., professor of military science at Fordham, at the Nov. 6 event at the Rose Hill campus. Today, the University is home to a military service community comprising “one of the most diverse [ROTC] cadet battalions in the Northeast” and more than 400 students who are veterans, he said, noting the University’s reputation for being welcoming to them.

“The military-connected community is one of the things that makes Fordham special,” he said. “This is a community that’s built around individual paths of service coming together in one place.”

Efforts to honor, support, and grow that community will be part of the yearlong anniversary celebration.

The Office of Military and Veterans’ Services and the Department of Military Science will host two events per month from January through November, with each month’s events organized around a chapter of military history at Fordham. January’s events include a service project—in partnership with Campus Ministry—related to welcoming immigrants, harking back to the origins of Fordham’s military training in 1848. Events in later months will commemorate the Civil War, Vietnam War, World War I, and other epochs, culminating in a gala to be held in November 2023.

There is also a “military muster” outreach effort to Fordham’s military community—ROTC graduates, student and alumni veterans, faculty and staff who served, and friends and family of Fordham veterans—to reengage them with the University. In addition, the veterans’ services office will lead an effort to raise $4.2 million to support ROTC cadets and student veterans as part of Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, the University’s $350 million fundraising campaign.

The veterans’ services campaign received some impromptu support at the Nov. 6 event, which celebrated two distinguished alumni veterans as well as the ROTC program and student-veteran community at Fordham.

Two Who Served with Valor

Attendees included alumni, student veterans, and cadets in Fordham’s ROTC program, a flagship program in the Northeast comprising cadets who attend 17 New York-area schools, from New York University to the Parsons School of Design, Tanghe said.

Two alumni veterans were inducted into the Fordham University Military Hall of Fame: William E. Kotas, FCRH ’69, a graduate of Fordham’s ROTC program, onetime U.S. Army captain, and Vietnam War veteran, who was honored posthumously; and retired U.S. Marine Corps Capt. Gerry Byrne, FCRH ’66, a Vietnam War veteran, media executive, community leader, and entrepreneur.

Kotas, who died last year, served as a platoon leader with the 23rd Infantry Division. He was inducted in honor of “the way that he approached all of his duties and obligations to others in his life,” from his cadet years to his post-Army life, Tanghe said.

“His military service was shorter than he wanted it to be because of the manner in which he approached it”—that is, with devotion to the soldiers under his command, Tanghe said.

In a display of that devotion, he personally led a patrol during which he suffered grievous injuries that would require a year of hospitalization and medical retirement from the Army. At the time of his injury, he continued to lead his men and directed them to safety. Kotas received multiple military honors, including the National Defense Service Medal, the Parachute Badge, and the Bronze Star Medal with the “V” device to denote heroism.

Moving back to Nashville, Tennessee, “he continued to find a life of purpose and meaning,” Tanghe said. Kotas was a founding member of the St. Ignatius of Antioch Catholic Church in Nashville and taught in its adult education program on Sundays, among other community activities, and worked for the U.S. Postal Service until his retirement.

Byrne, a 1962 graduate of Fordham Preparatory School, was commissioned via the Marine Corps’ Platoon Leaders Class, which he attended while earning his degree from Fordham College at Rose Hill. He served on active duty from 1966 to 1969, including a tour in Vietnam spanning the latter two years.

“What I learned at Fordham Prep and Fordham College from the Jesuits was ethics and integrity,” he told the gathering. “In the Marine Corps, I learned discipline and leadership. When you combine it, it’s amazing what you get out of it.”

Byrne has had a distinguished career in media, serving as launch publisher of Crain’s New York Business, creator and chairman of NBC’s Quill Awards, and publisher of Variety, leading its transformation into a diversified global media brand. Today he is vice chairman of Penske Media.

He has hosted a Marine Corps birthday celebration in New York City for the past 25 years, and in 2009, he received the Made in New York Award from then-mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Byrne serves on the boards of nonprofits too numerous to name, including the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum. He learned the value of staying busy, he said, from the famed television producer Norman Lear, who, during a conversation about packed schedules, told him that “life is not a rehearsal.”

“When I go back and think about friends and fellow marines who don’t have the ability to stand here like I am, it’s very moving,” said Byrne, who attended the event with some friends from the Corps and his wife, Liz Daly Byrne.

He said he was “extraordinarily honored” to be inducted into the Hall of Fame “and to be a Fordham graduate, and to see … everyone who’s here today.”

A Fundraising Campaign Begins

The fundraising campaign announced at the event has three components:

- An Emergency Relief Fund to promote wellness for military-connected students and provide loans to help students through financial distress ($100,000 goal)

- An endowment to enrich ROTC cadets’ and student veterans’ education by sending them to events and conferences, bringing guest speakers to campus, and providing gear needed for new training opportunities ($1.75 million goal)

- A drive to create a facility at Rose Hill for student veterans and cadets that promotes inclusion, community, collaboration, and information sharing, in part through new digital resources ($2.3 million goal)

Tanghe noted that the Emergency Relief Fund will provide microloans to help students who, for instance, might be unable to meet monthly living expenses on time, because their veterans’ benefit payments are held up by bureaucratic snafus. “If you’re missing a month of rent in New York City, that can be a significant financial burden,” Tanghe said at the Nov. 6 event.

Matthew Butler, PCS ’17, Fordham’s director of military and veterans’ services, said the fundraising effort has gotten off to a strong start, with one donor contributing $25,000 in mid-October.

During a follow-up meeting, the donor wrote another check, for $70,000, Butler said.

That’s when Byrne spoke up—“Liz and I will throw in the other five” needed to bring the tally up to an even $100,000, he said.

Asked later about his spontaneous decision to donate, he gave a simple reason.

“It’s supporting Fordham and veterans,” he said. “There’s no better reason than that.”

Register here to be connected with others in Fordham’s military-affiliated community.

To inquire about supporting the Office of Military and Veterans’ Services fundraising campaign, please contact Michael Boyd, senior associate vice president for development and university relations, at 212-636-6525 or [email protected]. Learn more about Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, a campaign to reinvest in every aspect of the Fordham student experience.

]]>“General, you will be remembered as one of the finest and most dedicated soldiers in a long and storied history of the United States military, no question about it,” the president said after describing Keane’s distinguished 38-year Army career stretching from his time as a cadet in the Fordham ROTC program to the Vietnam War to the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East.

Among other achievements, Trump said, Keane “designed new training methods to ensure that military leaders would always be extremely well prepared for the intensity of combat command,” and also designed “state-of-the-art” counterinsurgency combat training for both urban and rugged environments.

In his own remarks, Keane said he was “deeply honored by this extraordinary award.”

“To receive it here in the White House, surrounded by family, by friends, and by senior government officials, is really quite overwhelming, and you can hear it in my voice,” he said. “I thank God for guiding me in the journey of life,” he said, also mentioning his “two great loves”—his wife Theresa, or Terry, who died in 2016, and the political commentator and author Angela McGlowan, “who I will love for the remainder of my life.”

“With all honesty, I wouldn’t be standing here without their love and their devotion,” he said.

Fordham Ties

Keane is the sixth Fordham graduate to receive the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. The most recent alumni recipient was sportscaster Vin Sully, FCRH ’49, awarded the medal by President Barack Obama in 2016.

Keane has advised President Trump and has often provided expert testimony to Congress since retiring as vice chief of staff of the Army in 2003. He is a Fordham trustee fellow and a 2004 recipient of the Fordham Founder’s Award.

Keane grew up in a housing project on Manhattan’s Lower East Side and was the first member of his family to attend college. He had 16 years of Catholic education, including his time at Fordham, where there was a prevailing idea that “you should have a sense of giving things back, and finding ways to do that,” he said in an interview last week on Fox News Radio’s Guy Benson Show.

Six other Fordham alumni, including some who were his contemporaries at Fordham, attended the ceremony. One of them, Joe Jordan, GABELLI ’74, said he’s impressed with how Keane, on television, “can say so much in such a short time that makes sense.”

“He attributes a lot of it to the philosophy courses he took at Fordham,” said Jordan, an author and speaker specializing in financial services who met Keane about 15 years ago, when he was a senior executive at MetLife and Keane was on the board. “He’s a guy who’s extremely successful, extremely humble, has a common touch, and always remembers his friends and attributes a lot of his success not to himself but to the people around him, and the people who helped form him.”

Also in attendance was retired General Keith Alexander, former director of the National Security Agency, who has appeared at Fordham events, including the International Conference on Cyber Security.

Turning Points

Keane earned a bachelor’s degree in accounting and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1966. He became a career paratrooper, going to Vietnam to serve with the 101st Airborne Division, which he later commanded.

He was decorated for valor in Vietnam, which was a turning point for him, with its close combat in which “death was always a silent companion,” he said.

“It was there I truly learned the value of life, the value of human life—to treasure it, to protect it,” he said in his White House remarks. “The experience crystallized for me the critical importance of our soldiers to be properly prepared with necessary skill and the appropriate amount of will to succeed in combat.”

He said he spent his Army career “among heroes who inspired me, and I’m still in awe of them today.”

“My sergeants, my fellow officers, and my mentors shaped me significantly, and several times they saved me from myself,” he said. “That’s the truth of it.”

The 9/11 attacks were a second major turning point for him, he said. He was in the Pentagon when it was attacked, and helped evacuate the injured. He lost 85 Army teammates, he said, and two days later was dispatched to New York City to take part in the response to the World Trade Center attacks.

“It was personal, and I was angry,” he said. “I could not have imagined that I would stay so involved in national security and foreign policy” after leaving the Army, he said. “My motivation is pretty simple: Do whatever I can, even in a small way, to keep America and the American people safe.”

Watch the ceremony honoring General Keane

Several Fordham alumni attended a reception honoring General Keane on March 10. From left: Scott Hartshorn, GABELLI ’98; Phil Crotty, FCRH ’64; the Rev. Charles Gallagher, FCRH ’06; Paul Decker, GABELLI ’65; Laurie Crotty, GSE ’77; General Jack Keane, GABELLI ’66; and Joe Jordan, GABELLI ’74. On the right is Roger A. Milici, Jr., vice president for development and university relations at Fordham.

]]>On June 10, 1967—a time of mass protests against the Vietnam war and rising violence in the struggle for racial justice—the 41-year-old U.S. senator from New York reminded Fordham graduates that they were entering “a world aflame with the desires and hatreds of multitudes.”

He urged them to hear the voices of “the dispossessed, the insulted, and injured of the globe,” to heed their own revolutionary responsibilities, and to remember the difference that one person can make. And he quoted from his June 1966 “Day of Affirmation” address at the University of Cape Town during the height of apartheid in South Africa:

Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

“It was electrifying,” recalls William Arnone, FCRH ’70, who heard the speech from the back of Edwards Parade. Later that year, Kennedy’s staff came to Fordham to recruit students. “They said, ‘You can study politics or you can do it,’” Arnone says. “Next day, I showed up. I was hooked.”

He and several other Fordham undergraduates worked as constituent case aides in the senator’s New York office, fielding inquiries from New Yorkers in distress.

In the four-part Netflix series Bobby Kennedy for President, released last year, Arnone describes taking calls from single mothers in Harlem who struggled to protect their children from rats—and to get their landlord to help.

“I would get the name of the superintendent and the landlord,” Arnone says in the film, “and I would call them up: ‘This is William Arnone, I’m calling on behalf of Senator Robert F. Kennedy. There are rats in Mrs. Smith’s apartment, eating her children’s toes. What are you going to do about it?’ And I would get the same answer, ‘You mean Robert Kennedy cares about Mrs. Smith’s kids?’ ‘Yes.’

“I would get the name of the superintendent and the landlord,” Arnone says in the film, “and I would call them up: ‘This is William Arnone, I’m calling on behalf of Senator Robert F. Kennedy. There are rats in Mrs. Smith’s apartment, eating her children’s toes. What are you going to do about it?’ And I would get the same answer, ‘You mean Robert Kennedy cares about Mrs. Smith’s kids?’ ‘Yes.’

“Invariably I get a call the next day: They have an exterminator, no more rats. ‘Thank God for Mr. Kennedy.’”

In mid-March 1968, Kennedy launched his campaign for president, running on a platform of economic and racial justice, and an end to the war in Vietnam. “We all fed him things to use in the campaign,” recalls Arnone, who was ecstatic when Kennedy shared his story about the rats during a campaign speech. “But then he would send me notes and say, ‘Good job, you helped her. But we have to have the solution that’s systemic.’”

Kennedy’s campaign lasted less than 90 days. Shortly after winning the California primary, he was assassinated in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. He died on June 6.

Two days later, Arnone was at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan for Kennedy’s funeral Mass, after which he rode on the private train that carried Kennedy’s body from New York City to Washington, D.C., for burial in Arlington National Cemetery.

“It was just a nightmare, but it was poignant” seeing the hundreds of thousands of mourners who lined the tracks to bid Kennedy farewell, he said.

Arnone went on to a career focused on the elderly and retirement issues. He is the chief executive of the National Academy of Social Insurance, a Washington, D.C.-based nonpartisan think tank, and he remains inspired by Kennedy.

“He was fierce, passionate, and understood vulnerability in a way that was authentic, and it changed my life. His whole goal was to bring people together and try to avoid class warfare, avoid violence,” Arnone says. “To me, that’s the message for today.”

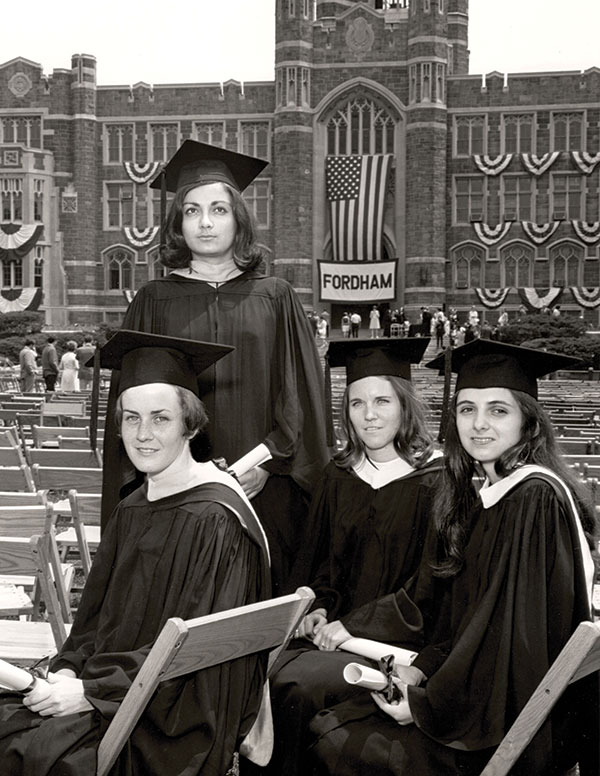

Mary Ellen Ross, Joanne Grossi, Cheryl Palmer Normile, and Susan Barrera Fay—a Fordham photographer brought them together on graduation day as representatives of their “pioneer class” of 210 graduates, the “first girls to invade the male environs of Rose Hill en masse,” as a University press release put it at the time.

They weren’t the first women to attend Fordham. Women had been earning Fordham degrees in law, education, social service, and other fields for nearly five decades. But they helped initiate a tremendous cultural shift at the University, one that culminated a decade later, when TMC graduated its last class and Fordham College at Rose Hill began accepting women. They challenged themselves and everyone around them—including skeptical faculty and students at the all-male Fordham College—to see beyond boundaries of expectations for women.

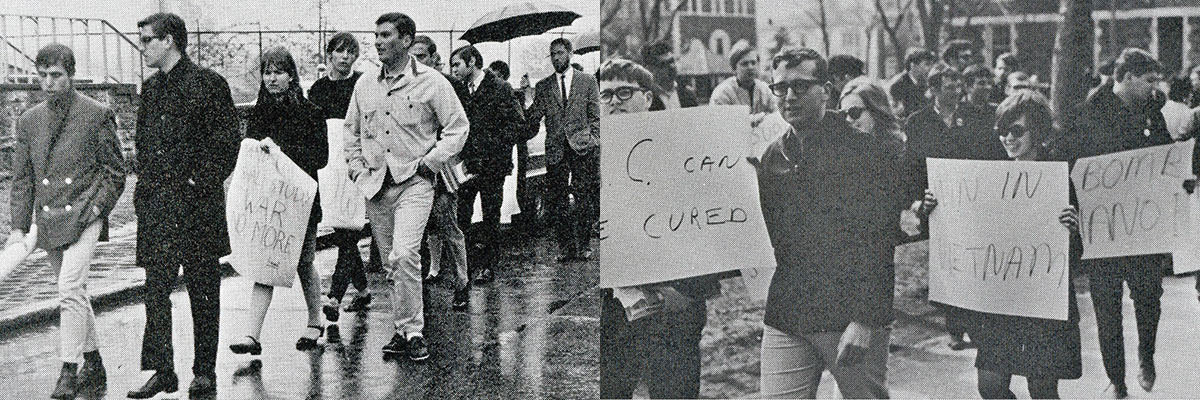

Their undergraduate days were also indelibly marked by social unrest—the civil rights and burgeoning women’s liberation movements, political assassinations, race riots, and anti-war protests that shocked and roiled the country.

“It really is hard to have perspective in the moment,” Normile said of being in the first class of TMC amid the “tumult” of the times. “But I think as women, we did have a sense that we were breaking some ground.”

Grossi expressed a similar sentiment. “When we got there,” she said, “we knew it was a big deal.”

‘She’s Done Well, She Deserves to Go’

Fay first visited Rose Hill for a debate workshop as a high school sophomore. “I thought it was a beautiful campus,” she said. So when she learned that Fordham was opening a college for women, she leapt at the opportunity. Admission was highly selective. In a letter welcoming the first incoming class to the University, Vincent T. O’Keefe, S.J., president of Fordham from 1963 to 1965, admitted, “[W]e don’t even know whether to call you freshmen or freshwomen.” But he praised their academic records: “Your College Board scores are collectively above average.”

Academic requirements were no problem for Fay, but finances were another issue. As the oldest of five children (the youngest was born while she was at Fordham), she wasn’t sure she would go to college at all. “My father said, ‘Maybe you should go to secretarial school, so when you get married and have children, you’ll have something to fall back on if you need it,’” Fay recalled. Not that he was unsupportive, she said, just worried about providing for the rest of the family. “And it was my mother, who had not gone to college, who put her foot down and said, ‘She’s done well, she deserves to go,’” Fay said.

Like Fay, Ross was already familiar with Fordham. She grew up on Perry Avenue in the Bronx, a 15-minute walk from campus, where her brother, Donald, was a senior and the student government president. “We were very different,” he said of his sister. “I was a glad-hander, and she was not, but she was very well organized.” Grossi remembers Ross as warm and well liked, and thinks her proximity to power, as it were, might also explain why she was elected TMC student government president. “There was a lot of, ‘Can you ask Don about it?’ or ‘Who do we see?’” Grossi recalled with a laugh. But the women were often on their own, and Ross felt the challenge of being first. “There was nobody to look up to,” she told the Fordham press office in her senior year. “We had to solve our own problems.”

‘They Were Not Ready for Us’

Most of the women were commuter students, as there were no campus residences for women until fall 1967. Grossi traveled from Jersey City, New Jersey; Normile from Mount Vernon, New York; and Fay from Queens. Ross walked to campus. Grossi’s and Normile’s parents eventually let them live in nearby apartments, both for the experience and, in Grossi’s case, because her science labs were early in the morning.

Some students lived in the Susan Devlin Residence, a Bronx boarding house for working women that was run by Catholic nuns and was so crowded, Grossi said, that some residents had to climb over other beds to get to their own.

“They got us admitted and got us seats in classrooms, but they were not ready for us,” she said, recalling a dearth of ladies’ rooms and places for the women to gather on campus. Funny and outgoing, she succeeded Ross as TMC student government president. She said the administration tried to keep women in separate classes at first, but “in a year or two, we took classes with the men. And I think most of the guys changed their minds and got used to us.”

In a history class her first year, Fay was the only woman among about 50 students, she said. She found the last seat, in the back, where she hoped to go unnoticed. No such luck. Her future husband, John Fay, FCRH ’68, came in late and stood behind her, stealing glances at her name on her notebook. “The attempt to keep classes separate broke down quickly,” said Fay, whose facility with Spanish—her father was from Ecuador—landed her in advanced Spanish literature instead of an intro, girls-only section. “I hadn’t had boys in class since the third grade, so it was a bit of an adjustment.” She added with a laugh, “As soon as we got to higher-level classes, they weren’t going to have [separate sections of]Chaucer for boys and for girls.”

In a history class her first year, Fay was the only woman among about 50 students, she said. She found the last seat, in the back, where she hoped to go unnoticed. No such luck. Her future husband, John Fay, FCRH ’68, came in late and stood behind her, stealing glances at her name on her notebook. “The attempt to keep classes separate broke down quickly,” said Fay, whose facility with Spanish—her father was from Ecuador—landed her in advanced Spanish literature instead of an intro, girls-only section. “I hadn’t had boys in class since the third grade, so it was a bit of an adjustment.” She added with a laugh, “As soon as we got to higher-level classes, they weren’t going to have [separate sections of]Chaucer for boys and for girls.”

Normile attended an all-girls Catholic high school and never doubted that she would go to college. She remembers her guilt at skipping class with a friend one day to visit the New York Botanical Garden. “I did it, but it just bothered me,” Normile said of their little adventure, “because I knew the tuition was a lot for my parents.”

‘Beyond Your Own Little World’

The first class of TMC was graduating just as protests against the Vietnam War were dividing campuses, including Fordham’s, where military recruitment became an increasingly contentious issue. “People didn’t want recruiters on campus,” Grossi recalled. “It was a difficult time.” Fay’s boyfriend (later husband) joined the ROTC because he figured it was better to go into the Army as an officer than to be drafted. “It was a looming reality,” Fay said of the war. Her husband was not deployed to Vietnam, but many Fordham alumni were: 23 of them were killed, including four members of the Class of ’68, one of whom, Staff Sgt. Robert Murray, FCRH ’68, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Normile recalled it as “a tense time, a disturbing time. But I think that kind of disturbance makes you think beyond your own little world,” she said, adding that a Jesuit education helped provide “a bigger balance” because it “encourages questioning, thinking, and exploring, and students were doing that on a much bigger level.”

Fay had an experience that took her out of her familiar world when she joined two mission trips to a sugar mill town in Mexico during the summers after her sophomore and junior years. She taught English classes there and lived in the parish rectory.

“It was an eye-opening experience for many of us, these privileged American kids going down to this little community where children had bloated stomachs and were walking around barefoot,” she said of the trips, which grew into the University’s Global Outreach program. “I think my attitude toward political and economic issues was shaped in part by seeing how people struggled to survive in Mexico,” she said, adding, “I also discovered I knew how to teach.”

Life After Thomas More

Fay and her husband were married in the University Church the year after graduation, and following moves to Hawaii, Chicago, North Carolina, and Texas, they eventually settled in Reston, Virginia, where they raised two children. She earned a doctorate in English from George Washington University and taught at Marymount University for 31 years before retiring in 2011.

Grossi majored in biology but also had a knack for computer programming. She worked in data processing at Con Edison and then at Chase Manhattan Bank, but both jobs proved unfulfilling, and the constant stress led to gastrointestinal troubles. The only thing that helped was visiting a chiropractor. “Even though people thought they were quacks, it worked for me,” said Grossi, who was so impressed she started chiropractic school herself in 1973 and became a practitioner. She retired on full disability in 1992 after being diagnosed with Lyme disease and lupus. “It’s very difficult, when you’re still in your early 40s, not to have a profession anymore,” Grossi said. “What do you do?” Volunteer work with the local YWCA is one thing that has kept her engaged.

Ross earned a Ph.D. in psychology at Syracuse University and was a professor of psychology and women’s studies for 30 years at St. Olaf College in Minnesota, where she found her niche.

Donald Ross remembers when he learned just how much of a difference his sister had made in the lives of her students. He was in Anchorage, Alaska, working on a juvenile justice project, and the administrator of a prison facility there had a St. Olaf mug on her desk. He asked her about it. She was an alumna, and she had known his sister. The woman began to cry when he told her that Mary Ellen had died, from Alzheimer’s, at age 66. “She said, ‘Your sister was so inspirational to all of the young women there, and treated us so well,’” he recalled.

Normile pursued a journalism career, which led to her becoming, she believes, the first female speechwriter on the staff of the secretary of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Being a groundbreaking woman in the federal government in the 1970s meant facing sexist attitudes, despite holding a master’s degree from American University, Normile said. She left the USDA in 1981, got married, and later spent two years working on the Democratic Study Group of the U.S. House of Representatives before taking time off to raise two daughters and care for her parents. She returned to the USDA as a speechwriter in 1992, retiring in 2015. Her husband, Michael, died that same year.

Looking back, she attributes her decision to become a writer in part to William Grimaldi, S.J., a Fordham classics professor who encouraged her to go to grad school. “It was because of him that I came to D.C.,” she said.

Fay was also friends with Father Grimaldi—he presided at her wedding and baptized her children. Years later, when he was visiting the Fays at their home, they fell into conversation about the impact of women at Fordham. They reminisced about those days when everyone was navigating unfamiliar waters, students and Jesuits alike.

“He had thought it was not a very good idea” at the time, Fay said, “but over the years, he realized it was the best thing that happened to Fordham.”

—Julie Bourbon is a writer and editor based in Washington, D.C.

]]>In 1966, when Ruppel was a sophomore English major, he booked both the Beach Boys and the Lovin’ Spoonful for a concert in the Rose Hill Gym. Managing the tension between the two groups—who were mistakenly placed in the same dressing room—turned out to be harder than getting them to campus in the first place.

“I remember walking into George McMahon’s office,” he says, referring to the Jesuit priest who was then dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill, “and telling him that I had this contract for a group called the Beach Boys to come and perform. And oh, by the way, I need a check for $3,750 to make the deposit,” Ruppel says, laughing.

Father McMahon gave him the check after Ruppel assured him that the concert committee would sell enough tickets to reimburse the dean’s account.

“I don’t know that I would have done that if I was him, quite honestly,” says Ruppel, who is now a Fordham trustee. “So when I say Fordham was nurturing, I mean it in a big way.”

Rockin’ Rose Hill Again

Ruppel’s love for the classic rock hits of the ’60s is one of the things he has carried away from his time at Fordham. He and his wife, Patricia, who Ruppel says has “adopted Fordham,” are both big fans of the Beatles, and are looking forward to sharing their love of the Fab Faux with Fordham during a private concert for alumni, faculty, and staff on Friday, June 1, to help kick off Jubilee Weekend. “In our opinion there’s nobody who plays Beatles music more faithfully,” Ruppel says, “and they don’t try to look or act like them.”

Ruppel is also looking forward to reconnecting with his classmates during Jubilee (June 1 through 3), including those who helped him plan his class’s memorable sophomore spring concert.

“It’s been my experience that when you see a classmate, even if you’ve not seen them since the last reunion, you just pick up where you left off,” he says. “You have the same affinity as before. Friendships from that era are very special because of that shared formative time.”

Sharing the Experience

Ruppel says that he has felt “really fulfilled by my college experience,” and that’s why he and his wife started the Dennis and Patricia Ruppel Endowed Scholarship Fund at Fordham.

“I know Fordham has changed, and I’ve changed, and times have changed, but I still believe there’s a core that persists,” he says. “And I would really prefer that anybody who wanted to attend Fordham would not be prevented from doing so because of money.”

Ruppel’s history of supporting education dates back to his two-year stint as a social worker shortly after he graduated from Fordham. As a registered conscientious objector during the Vietnam War, he deferred his law school acceptance and was assigned to work for the Department of Families and Children’s Services in his native St. Petersburg, Florida, where he still resides.

“It turned out to be an absolute blessing,” Ruppel says of the experience, which exposed him to a level of poverty he had not been fully aware of while growing up in the area. “It became very clear to me that education was really the only path out of that economic deprivation, and if the youngest kids were not prepared for school before they got there, there was little chance they would succeed.”

While he now juggles multiple professional roles—as a lawyer, a chairman of both a bank and an insurance company, and a co-owner of a hotel in Maine—he has remained committed to educational causes.

“We’ve been fortunate enough in our lives that we have the resources to make contributions,” Ruppel says, “and one of the things we care about is helping provide students with a high-quality education.”

Fordham Five

What are you most passionate about?

I am most passionate about quality preschool education, especially for the economically disadvantaged. Our future and their future is highly dependent on their school readiness. Studies show that quality in this arena makes a material difference.

Some of this passion stems from my own experience as a single parent of two preschoolers while I was attending law school. I vowed then it was a cause I would support for my lifetime. I have been fortunate to do so. For 30 years I have served on the board of directors for R’Club Child Care in St. Petersburg, Florida, a local nonprofit that currently cares for more than 4,000 children per day in highly educational and nurturing settings.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

My dad, who was an incredible mentor, told me that the most important decisions in life are picking one’s partners—whether that be your spouse, friends, law partners, or business partners—and that there is no more important activity in life than nurturing those partnerships.

What’s your favorite place in New York City? In the world?

In New York City, the New York Yacht Club. Its architecture, art, and nautical artifacts and models collectively make it the Sistine Chapel of sailing. It is our home when my wife and I are visiting New York; I discover something new on every visit.

My favorite place in the world is Maine in the summertime and early fall. We are fortunate to have a summer home there and make it our base from June to mid-October. Our family and friends share time with us there. I love the people, the environment, and climate. It’s a thoroughly restorative place.

Name a book that has had a lasting influence on you.

The entire Bob Dylan songbook. I remember clearly the first time I heard his music in the dorm room of a friend near the beginning of my first year at Fordham. I was immediately captivated by Dylan’s mastery of words and moments. To this day, at times of quiet, it is most often his words and lyrics that come to me. It’s a lifelong love for sure.

Who is the Fordham grad or professor you admire most?

John Costantino—who was recently and justly honored at the Fordham Founder’s Award Dinner—is the Fordham grad I most admire. A true Fordham man, always gracious and thoughtful, a lifelong learner with the courage to take well-thought risks and who always shares his wonderful sense of humor. I admire his loyalty to family, friends, and Fordham.

And Nicholas Loprete was the English literature professor who opened my eyes to the depth and wonders of fiction and poetry. He loved what he taught. He taught me to love it too.

]]>

In The Gamble, his 2009 book on the Iraq War, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Thomas Ricks described Jack Keane, a retired four-star general, as “crackerjack smart and extremely articulate, often in a blunt way. Most importantly … he is an independent and clear thinker.”

Keane began his military career at Fordham as a cadet in the University’s ROTC program. He graduated in 1966 with a bachelor’s degree in accounting and went on to serve as a platoon leader and company commander during the Vietnam War, where he was decorated for valor. A career paratrooper, he rose to command the 101st Airborne Division and the 18th Airborne Corps before he was named vice chief of staff of the Army in 1999.

Since retiring from the military in 2003, Keane has been an influential adviser, often testifying before Congress on matters of foreign policy and national security. In late 2006 and in 2007, he was a key architect of the surge strategy that changed the way the U.S. fought the war in Iraq. He is a trustee fellow at Fordham; a member of the board of directors of General Dynamics, an aerospace and defense company; and chairman of the board of the Institute for the Study of War, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank that monitors global conflicts. He’s also a senior national security analyst on Fox News.

Keane spoke with FORDHAM magazine about service, leadership, and whether or not his loyalties will be divided on Sept. 1, when Fordham football opens its 2017 season with a game against Army at West Point.

What inspired you to join the Army?

I joined the ROTC program essentially because the country was at war and we knew that we would likely be joining it. In the mind of myself and my friends, it made sense to do that as officers, although none of us had ever had a family member who was an officer. Then, as part of the ROTC program, I joined the Pershing Rifles [national military society] because they seemed more confident and accomplished than the other participants in ROTC.

We took basic marksmanship training, and we would go to Camp Smith and practice patrolling techniques and other tactics under the supervision of active-duty officers. That gave me some exposure to what I thought the Army would be like. By the time I graduated, I came to recognize that I had an aptitude for it. And I liked the idea of serving the country.

I saw an interview you did a few years ago with Bill Kristol. You told him about a conversation you had with a Jesuit around the time you were graduating from Fordham. Who was that Jesuit and what did you two talk about?

I think it was Father [Thomas] Doyle, [then an assistant professor of philosophy], but I’m not sure. He asked me what I was planning to do, and I said, “I’m going to go in the Army.” He said, “No, I mean, after the Army.” I said, “Well, I’m thinking about maybe making a career out of it if I’m capable and if I like it to the degree that I think I will.” He said, “Why would you do that? You have so much more to offer.”

I said, “Well, Father, have you ever been associated with the Army? Were you a chaplain?” He said no. I said, “Well, I’ve spent a lot of time around it and people who serve in it, and I don’t think it’s necessarily what you think it is. I think there’s an incredible amount of opportunity for growth and development as a human being. I think I’ll have the freedom of thought and the opportunity to be very challenged, and I think that will lead to a growth experience for me.”

That turned out to be the case.

The way you describe the Army, in terms of opportunities for growth within a strict organizational structure, could also be applied to the Jesuits, I would think. You went to Catholic schools before Fordham, but was Fordham your first encounter with the Jesuits?

I told my new Army friends that after 16 years of Catholic education, the transition to the Army was very smooth! I think of Fordham and the Jesuits as a transformational experience. The rigor of the Jesuit methodology was evident in all classes. What they were least interested in is regurgitation of information. What they’re most interested in is critical thinking based on analysis and some rigorous method of interpretation using reasoning.

That was challenging because it was completely different than my Catholic high school. I thought college was just going to be high school on steroids. At Fordham, it was quite something else. The whole learning process was about your own growth and development as a human being—not just intellectually but also morally and emotionally. I don’t think I would have been as successful as a military officer if my path didn’t go through Fordham University.

Would you talk about your approach to leadership and how it has evolved since your days as a platoon leader? Are there certain qualities that you feel all effective leaders share?

First of all, there are very few natural-born gifted leaders. Most leaders learn from experience. If you’re in the United States military and you start out as a second lieutenant platoon leader with 40 people, your life from that moment on is a leadership laboratory. You have plenty of opportunity to learn and also to observe leaders who are very effective.

When you really get down to it, what you’re doing is motivating and inspiring others to reach their full potential and to do that collectively as an organization. Whether it’s a small team or a large team, the opportunity to learn and to grow is really quite extraordinary.

Some of that for me was in combat, which is such an extraordinary human experience. Everything that you are as a person—your character, your intellect, your moral and physical courage—is brought to bear under significant stress. People’s lives are dependent on you. You’re not only there to protect the civilian population and protect your own soldiers; you’ve been given the authority to take lives. The moral underpinning for something like that is really quite significant. I think having had 16 years of Catholic education and participating at Fordham, where I took four years of theology and four years of philosophy, which were my favorite courses, by the way, really provided me with the wherewithal not only to cope with combat but to perform to a high standard.

With regard to leadership, anybody can make a list of attributes leaders have to have—integrity, judgment, moral underpinning, et cetera. But there is one attribute that’s always stood out for me, and that’s perseverance. You have to persevere to accomplish the mission. Whether that’s in a stressful situation like combat or in other environments, perseverance really can be very defining because there are constant impediments and obstacles. You see people, not just in the military but in all walks of life, who because of those obstacles and impediments accept something less. They could continue to drive on. Most of the time, it’s more about mental toughness than it is about physical toughness.

Two years ago, Fordham ROTC established the General Jack Keane Outstanding Leader Award, to be given each year to a graduating cadet. What does that award mean to you, and what advice do you give newly commissioned officers?

I was honored to give out the first General Jack Keane Award [at the University Church in 2015]. And I was quite humbled by it, to be frank, when I got my head around the fact that they will always give this award to somebody who is outstanding as a cadet and likely more outstanding than I was.

I’ve always told my officers and my generals that we’re in leadership positions because we know how to lead effective organizations; we get results. But our legacy is not how well we run these organizations, because there’s another guy or gal standing behind us who could run it even better. The real legacy is the growth and development of the people in these organizations. If you focus on their growth and development, and if you have programs that support that, the organization will take care of itself. The organization will actually blossom because the people in it are so committed to it and have a very high degree of satisfaction. That is your legacy.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

It came from a sergeant major. I was a major at the time. I was very intense, working very hard, and I was a little frustrated with my boss, my battalion commander, who wasn’t paying attention to all the things I thought he should be paying attention to. The sergeant major closed my office door and said to me, “Major, I know you’ve got some things that are bothering you. I want you to know just one thing: You’re responsible for your own morale.” He looked at me and said, “You got it, sir?” I said, “I got it, sergeant major, thank you very much.”

I never forgot that. It was sound advice.

Fordham football is playing Army at West Point on September first. Who will you be rooting for?

I’m going to miss the game, unfortunately, but good Lord, I want to beat those guys. When I go to West Point for the game, I usually talk to the corps of cadets about the U.S. global security challenges: the Middle East, Russia, the problems with Al Qaeda and ISIS, et cetera. After I spoke a couple of years ago, the first question I got was from a cadet. He said, “General, so we understand you went to Fordham University. You spent almost 40 years in the Army, and you spent only four years at Fordham, so I’m assuming you’re rooting for Army.”

He was just having fun with me, but I looked at him. I said, “Are you kidding me? You know damn well who I’m rooting for tomorrow, OK? I’m rooting for my alma mater.”

So yes, I want both teams to play well, certainly, but I definitely want us to win.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Ryan Stellabotte.

]]> The Signal Flame: A Novel by Andrew Krivák, GSAS ’95 (Scribner)

The Signal Flame: A Novel by Andrew Krivák, GSAS ’95 (Scribner)

In his first novel, The Sojourn (a finalist for the National Book Award in 2011), Andrew Krivák told the story of Jozef Vinich, a sharpshooter in the Austro-Hungarian Army who survives World War I and immigrates to America with $50 in his pocket. He settles in northeastern Pennsylvania, rises from yard worker to co-owner of a roughing mill, and acquires 2,000 acres of land on which he builds a large home for his wife and children. But he and his descendants are a “war-haunted family in a war-torn century.” The Signal Flame, set in 1972, begins with Vinich’s death. As his daughter Hannah and grandson Bo mourn, they grapple with the news that Bo’s younger brother, Sam, who joined the Marines, has been reported as missing in action in Vietnam. They also grapple with the legacy of Sam and Bo’s father, who came home from World War II a silent, damaged man and was later killed in a hunting accident. “What they shared were the wars,” Krivák writes in a lyrical prologue to a lyrical, moving novel on the meaning of love, loss, and loyalty.

The Streets of Paris: A Guide to the City of Light Following in the Footsteps of Famous Parisians Throughout History by Susan Cahill, GSAS ’95 (St. Martin’s Press)

The Streets of Paris: A Guide to the City of Light Following in the Footsteps of Famous Parisians Throughout History by Susan Cahill, GSAS ’95 (St. Martin’s Press)

Susan Cahill first visited the City of Light during the 1960s, on her honeymoon with her husband, the writer Thomas Cahill, FCRH ’64. It’s a place, she writes, where “the streets are stories.” She takes readers through them in this travel guide, following the lives of 22 famous Parisians from the 12th century to the present. She writes about “The Scandalous Love of Héloise and Abelard,” “The Lonely Passion of Marie Curie,” and “Raising Hell in Pigalle,” where the “scruffy streets of the ninth were François Truffaut’s muse and mother.” Each chapter includes a lively cultural history, plus information about nearby attractions. The result is an engaging guide for travelers drawn to stories that, Cahill writes, “do not show up on historical plaques or in the voice-overs of flag-waving tour guides.”

Pause: Harnessing the Life-Changing Power of Giving Yourself a Break by Rachael O’Meara, GABELLI ’04, (Tarcher Perigee)

Pause: Harnessing the Life-Changing Power of Giving Yourself a Break by Rachael O’Meara, GABELLI ’04, (Tarcher Perigee)

Six years ago, Rachael O’Meara was a customer support manager at Google. The job made her “the envy of all my friends,” she writes, but she was burning out fast, feeling overwhelmed, unfulfilled, and unable to find the off switch. Her work and well-being suffered. Eventually, with support from her boss, she took a 90-day unpaid leave and returned to the company in a new role, with a healthier outlook. In this book, she shares her story and stories of others who have discovered that a pause, even a “forced pause” like getting laid off, can lead to a more fulfilling life. She offers tips for creating a daily “pause plan.” It can be as simple as a five-minute walk or a day unplugged from digital devices, she writes, but the benefits are priceless: greater “mental clarity” and “a chance to remember what ‘lights you up.’”

]]>