That’s the question recently addressed by a Fordham student’s faculty-mentored research project. While scholars have long suspected that people with disabilities tend to get left behind in schooling, in employment, and in other sectors of life, the research by Emily Lewis, FCRH ’22, found that there is even more of this inequality in richer countries. And it suggests that policies may be needed to ensure growth and development benefit all people in a society.

Disability “tends to be ignored when we speak about inequalities,” said economics professor Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., co-director of the disability studies minor and founding director of Fordham’s Research Consortium on Disability. “And yet, disability is key when it comes to understanding people’s livelihoods, people’s standard of living.”

Mitra was the mentor for Lewis, an economics and philosophy major who spent last summer analyzing international disability data with support from a summer research grant. Such funding for student-faculty research is a priority of the University’s current fundraising campaign, Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student.

Lewis, Mitra, and economics doctoral candidate Jaclyn Yap are co-authors of the resulting research paper, Do Disability Inequalities Grow with Development? Evidence from 40 Countries, published April 25 in the academic journal Sustainability. The research sprouted from another project led by Mitra that highlights disability inequalities worldwide.

The Disability Data Initiative

Since 2006, more than 180 countries have ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, an agreement to treat them not as objects of charity and medical treatment but rather as contributing members of society.

To support this goal and help policymakers move forward, Mitra spearheaded the Disability Data Initiative, a report on 180 nations’ census and survey findings regarding people with disabilities from 2009 to 2018. She led a team of graduate and undergraduate students, including Lewis.

Presented at a UN conference last June, the report showed that about one-quarter of nations didn’t ask about disability in their national surveys. In those that did, the data showed major gaps in the areas of education, health, employment, and standard of living between people with disabilities and those without them.

The database opened the possibility of doing an extensive study across countries to see if these gaps increased with development—something that had been long hypothesized but not tested on a large scale.

Eager to explore this question, Lewis made it her summer project. Her interest in the disability gap had been sparked during one of Mitra’s classes, at a time when she was looking for a way to get involved in undergraduate research.

“Seeing examples of how different researchers are approaching these questions was really interesting, and got me excited about how I could design this project for myself,” she said.

It was a big project—and a summer research grant gave her the means to spend the required time on it.

Help from a Fordham Benefactor

This and other grants to students were made possible by an alumni benefactor who has long funded undergraduate research—Boniface “Buzz” Zaino, FCRH ’65, whose long career in the investment world exposed him to the joys of researching and learning about new industries. “Once I got into it, it just opened the world, because you do get to explore and focus on areas that become very interesting,” he said.

He has funded students’ research for years, energized by the students’ enthusiasm for their projects, by what their projects have taught him about the world, and by the benefits to the student researchers themselves.

The research process, with its wide reading and focused inquiries, gives students a base for developing their interests and learning about new things over the long term, he said. “The University provides a student with the opportunity to develop a research process, and that’s got to be very helpful for them going forward, no matter what they do in life,” he said.

The Disability and Development Gap

Lewis met weekly with Mitra over the summer to design and carry out the project, examining 40 countries that have comparable data on peoples’ self-reported difficulties with seeing, hearing, walking, cognition, self-care, and communication.

Working on the Disability Data Initiative, they had already gotten glimpses of a wider disability gap in wealthier countries.

For instance, in low-income nation of Cambodia, 75% of adults with any kind of difficulty caused by disability were employed, just shy of the 79% for those without disability. But in economically booming Mauritius, an island nation in the Indian Ocean, the gulf is far wider, with just 15% employment for those with any difficulty, compared to 56% for those without.

To see if such disparities represented a trend, Lewis crunched a big data set including lots of variables—levels of disability, gender, age, and urban versus rural location, as well as a nation’s place on Human Development Index, or HDI, a UN indicator of nations’ wealth and overall development.

She found that for many standard-of-living indicators, like adequate housing and access to electricity, there was little difference in the disability gap between richer and poorer countries.

But the story was different in three areas: education levels, employment rate, and a multidimensional measure of poverty. Gaps in all three increased as countries’ HDI increased. The results held up when Lewis looked at the data a few different ways, such as focusing on different development measures or population subgroups.

The results, the co-authors wrote, “suggest that as a country develops, policies, specifically in relation to education and employment, need to be implemented to narrow and, eventually, close the gaps between persons with and without disabilities.”

The research shows that while disparities may be greater in wealthier nations, disability inequalities aren’t just a problem in rich countries with older populations, Mitra said. Low-income countries have them too, even if they’re less pronounced.

“Even when almost everyone is poor, well, people with disabilities seem to be even poorer,” she said.

Lewis found it exciting to be involved in the research process and see it through from start to finish—figuring out the approach, changing direction as needed, and working independently. “[It’s] something I consider myself really lucky to have been involved in,” said Lewis, who was planning to work as a project assistant at a New York law firm after graduation to explore her interest in law school.

Mitra said that undergraduate research not only teaches students valuable skills but also gives them an inside look at how knowledge is produced, as well as all the caveats and limitations that come with it—an awareness that will serve them well in whatever field they pursue.

The University’s research grant program for undergraduates is “a unique opportunity for students, but also for as faculty,” Mitra said. “So I hope it does continue to attract the generosity of donors.”

To inquire about giving in support of student-faculty research or another area of the University, please contact Michael Boyd, senior associate vice president for development and university relations, at 212-636-6525 or [email protected]. Learn more about Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, our campaign to reinvest in every aspect of the Fordham student experience.

]]>The coalition has more than 50 representatives from non-governmental psychology organizations, including Fordham faculty and alumni—most notably, PCUN’s president, David Marcotte, S.J. The scholars work together to develop research-based recommendations for policymakers at the U.N.

“The primary goal of PCUN is to promote evidence-based policies,” said Harold Takooshian, Ph.D., PCUN’s treasurer and secretary and professor of psychology and urban studies and director of the organizational leadership program at Fordham. “We behavioral scientists feel that the best way to make policies is based on evidence. We conduct research on timely topics like migration and hunger, and research helps us find better solutions to problems.”

Throughout the pandemic, PCUN not only continued to work, but experienced its greatest growth, including a new book series that released its latest book this May, said Takooshian. Thanks to virtual programming, PCUN was able to increase the number of participants in its annual U.N. Psychology Day celebration from hundreds of people at an in-person gathering to nearly 2,000 virtual registrants in a Zoom call last year, said Takooshian. PCUN also started a monthly webinar series where scholars are invited to discuss their work, including renowned psychologist Philip Zimbardo, Ph.D., and Fordham GSS associate professor Marciana Popescu, Ph.D., an expert on forced migration.

‘We Need Help From Everyone’

One of PCUN’s biggest contributions is its book series on how scholars can use behavioral science to address today’s global challenges, particularly the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals for 2030—a list of global challenges that the U.N. aims to address.

All three books in the series can be used as resources in college courses related to psychology, social work, and international studies, said Takooshian. The books can also help people become more aware of timely issues—not just scholars, but people from all walks of life, said Elaine Congress, Ph.D., a book editor for this series and associate dean and professor at GSS.

“Psychologists and social workers don’t have all the answers. There are so many problems facing the world, and we need help from everyone,” said Congress, a social worker who serves as the the main representative of the Fordham NGO at the U.N. “Our book contributors—psychologists, social workers, U.N. officials, heads of NGOs, and experts in other fields—really manifest this. It’s important that this is a multidisciplinary effort.”

Researching Life-Changing Conditions and Potential Solutions

The book series was developed by not only Fordham professors, but also undergraduate and graduate students, some of whom are now alumni.

Sanhaya Soi, FCRH ’21, connected with Sameena Azhar, Ph.D., assistant professor at GSS, over their shared Indian heritage, and they collaborated on a chapter about mental health in India in the most recent book, Behavioral Science in the Global Arena: Global Mental, Spiritual, and Social Health.

“The way that mental health is viewed in Eastern societies versus Western societies is pretty different. In individualistic nations like America, mental health has a scientific outlook. In India, mental health is seen in regards to what karma or fate you are born with,” said Soi, who was born and raised in India and immigrated to the U.S. four years ago.

Soi said she hopes her chapter helps people understand how stigmatization of mental health developed in India and other countries—an issue that will continue to stay relevant after the pandemic is over.

“Mental health is something that people have been struggling with since the beginning of time,” said Soi, who earned her bachelor’s degree in psychology at Fordham and now works as a recruitment consultant for Kintec Search, Inc.

Shenae Osborn, GSS ’21, who earned her master’s degree in social work and interned at the U.N., co-edited two books and co-authored two chapters. One of her book chapters, which will be published in the upcoming book Behavioral Science in the Global Arena: Global Health Trends and Issues, describes the difficulties of caring for a family member with dementia—an illness that is on the rise—and explains how to support people with dementia and their caregivers. Her other chapter, published in Behavioral Science in the Global Arena: Global Mental, Spiritual, and Social Health, shows how Christians and Jews often turn to their religion for hope, especially when they encounter a difficult situation like a terminal health diagnosis.

Osborn, a psychotherapist and volunteer U.N. representative for the International Federation of Social Workers, said that she hopes her overall work makes a difference in the world.

“I have had the opportunity to work on improving policies to reflect real modern-day situations like COVID-19,” said Osborn, a California native who plans to own her own practice where she can continue to work with low-income individuals. “My contribution, although small, is still a step in making a difference.”

A Longtime Relationship with the United Nations

Fordham’s relationship with the U.N. extends beyond PCUN. In 2013, Fordham became one of 16 universities to work with the UN as a non-governmental organization (NGO) that raises public awareness about U.N. activities and global issues. Fordham and the U.N. have co-hosted events, including the U.N.’s first International Educational Day. The University has also selected students for leadership training at the U.N. and developed a special field practicum for Fordham social work students who intern at U.N.-affiliated organizations.

Takooshian said he hopes that PCUN will continue to help scientists reach policymakers, particularly with its book series that will expand in the coming years.

“Almost everything related to peace, urbanization, and health is behaviorally-based. That is, human behavior shapes these problems,” said Takooshian. “The premise of our book series is that studying human behavior is able to reduce the problems, and I’m glad to say that the U.N. itself embraces what we’re talking about. In the past three years, they started a behavioral science unit. PCUN does not work with them yet—but it’s just a matter of time.”

]]>Selwin Hart, special adviser to the secretary-general on climate action and assistant secretary-general for the Climate Action Team at the United Nations, addressed students and staff about the recent developments in climate negotiations at the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (COP 26) held in Glasgow from Oct. 31 to Nov. 12 of this year.

Hart, a 2000 graduate of the Fordham IPED program, offered his thoughts on how the world must act in the face of the pandemic recovery and worsening climate crisis.

“Geopolitical tensions point to confrontation, competition, and potential conflict at a time when collaboration, cooperation, and solidarity are needed more than ever to ensure an inclusive recovery and to address the climate crisis,” he said.

Hart was the Cassamarca Lecturer at the “Climate Change and UN Call to Action” event delivered in Tognino Hall. The event was hosted by Fordham’s Graduate Program in International Political Economy and Development (IPED) and co-sponsored by Fordham Students for Environmental Awareness and Justice.

Hart said that at the Glasgow climate negotiations—the most consequential climate negotiations since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015—efforts were made to create multilateral agreements focused on addressing key issues concerning climate change.

The first goal from the conference was to keep the 1.5°C of warming goal within reach, which is the warming threshold agreed upon by most climate experts needed to avoid catastrophic damages from climate change. In other words, the world needs to limit greenhouse gas emissions such as carbon dioxide—the cause of rising temperatures—in order to limit the rise in Earth’s temperature to only 1.5 °C.

“The 1.5 °C goal is alive, but it is on life support, it will depend on what happens this decade, and more importantly in the next two to three years,” he said,

The second goal was to have developed countries deliver on their commitment to supporting emerging economies with $100 billion in climate financing, which Hart said should be completed by 2023. The third and final goal was to develop support for countries that are already facing climate impacts. An agreement was made on this front to double climate adaptation funding by 2025.

Hart said that the U.S. and China issued a joint statement at the conference committing to work together on climate-related actions, which he noted is substantial given the current geopolitical tensions.

Hart remains optimistic about the progress made at the negotiations, but he knows that challenges lie ahead.

“Multilateralism is at a crossroads; for multilateralism to be effective it needs the support and leadership of the largest players like the U.S. and China, but the voices of the smallest players in the international community also must be heard. It is imperative that they are heard and not sacrificed.”

Coming from the small island nation of Barbados, Hart has a unique perspective on these issues. He explained the triumph of the small island states, who, with the U.N., were part of initial the coalition to push for the 1.5 °C warming goal, and through the tools and levers of multilateralism, were able to successfully advocate and advance it.

Hart gave his warm appreciation to IPED Director Henry Schwalbenberg, Ph.D., who, over 20 years ago, offered Hart a fellowship to study at Fordham, which he says launched his career. Since then, Hart has been a chief climate change negotiator for Barbados as well as the ambassador of Barbados to the United States, prior to being appointed to his current U.N. position.

To bring the discussion closer to home, Marc Conte, Ph.D., of the Fordham Department of Economics delivered remarks on climate and climate action within the United States. He highlighted the importance of information in future actions and argued that if we do not have the correct information, or if real estate and other commodities are not indicative of perfect information, we will not be able to treat the climate crisis with the urgency it deserves. He pointed to the example of multimillion-dollar properties still being sold on Florida waterfronts, even with the threat of sea-level rise.

He also connected the issue to health.

“If we had more information about these benefits and costs to society of adverse health outcomes, we might be more willing to contribute and collaborate,” he said, adding that the U.S. can and should be a global leader in climate, as it has been the biggest cumulative emitter of greenhouse gases throughout history.

In closing, Hart connected the discussion on multilateralism with climate action by saying we should “try hard at all times to understand, in the true Fordham style, the perspectives and views of those that are across the table. There is always hope for finding common ground.” He emphasized that while progress is incremental, he still believes we can solve the climate crisis.

–Kevin Strohm

]]>

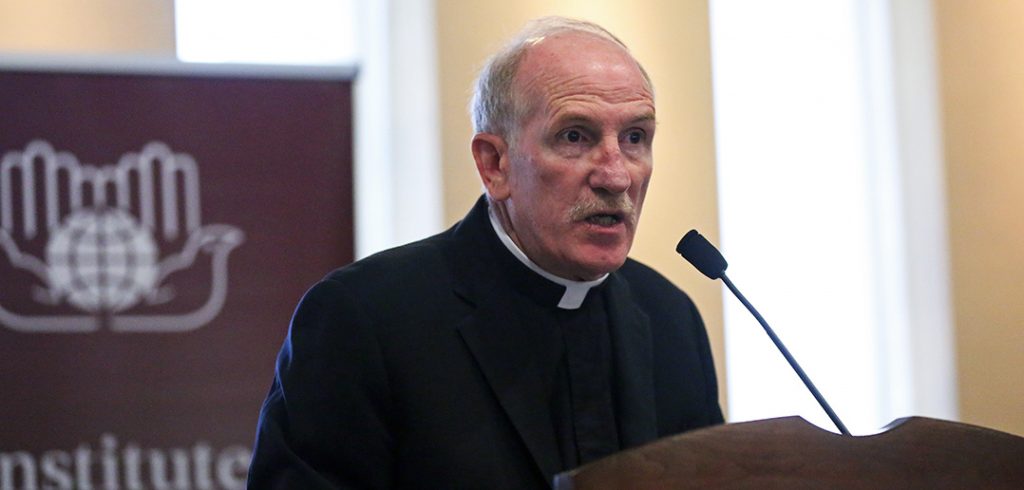

On Nov. 28, Silvano Maria Tomasi, C.S., and 12 others will join the College of Cardinals, a group of principal assistants and advisers to the pope. Pope Francis recently gave the archbishop another role as well: On Nov. 1, he named Tomasi his special delegate to the Sovereign Order of Malta, a lay religious order doing service work in 120 countries.

Archbishop Tomasi, 80, and three other cardinals-elect are above the cutoff age for taking part in the conclave that selects the next pope, the Vatican noted in its Oct. 25 announcement. Only cardinals younger than 80 can participate.

The archbishop is a “missionary scholar true to his order’s charism to work with immigrants,” said Gerald Cattaro, Ed.D., executive director of Fordham’s Center for Catholic School Leadership, who most recently saw Tomasi in Rome in December 2019 at a meeting of NGOs associated with the Holy See.

Archbishop Tomasi belongs to the Scalabrinian order, devoted to serving migrants and refugees. A naturalized American citizen, he earned his doctorate in sociology from Fordham in 1972, and is a co-founder of the Center for Migration Studies of New York, which has collaborated with Fordham on migration studies in the past.

He originally came from Italy to the U.S. to work among Italian immigrants, “and never forgot his call to work with those on the periphery,” Cattaro said. “His life’s work has been on behalf of the marginalized, in particular immigrants and refugees. That is, perhaps, why I believe [Pope Francis] chose to honor him with the ‘red hat,’” Cattaro said, referring to a cardinal’s traditional headpiece.

In the 1980s, Tomasi served as the first director of the Office for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. He has held high-level Vatican posts including secretary of the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant Peoples.

From 2003 to 2016, he served as permanent observer of the Holy See to the U.N. in Geneva. He has worked on human rights issues and also led the Vatican’s efforts toward nuclear arms control in recent years.

A Friend to Fordham

Archbishop Tomasi has helped Fordham build closer ties with the Mission of the Holy See to the U.N. and create opportunities for students in the International Political Economy and Development (IPED) program, such as serving the mission as diplomatic fellows at the U.N. in New York, said the program’s director, Henry Schwalbenberg, Ph.D.

Also, interest in Tomasi’s work at the U.N. contributed to IPED founding its annual Pope Francis Global Poverty Index in response to the pope’s call for a broad but simple measure of global poverty and well-being, Schwalbenberg said.

He said he thinks Tomasi’s appointment reflects the pope’s concern with the suffering of migrants. In public statements, Francis has sounded the alarm about the urgent needs of people being displaced around the world.

“Situations of conflict and humanitarian emergencies, aggravated by climate change, are increasing the numbers of displaced persons and affecting people already living in a state of dire poverty,” he said in a January address to members of the diplomatic corps accredited by the Holy See. “Many of the countries experiencing these situations lack adequate structures for meeting the needs of the displaced.”

In his message for the 106th World Day of Migrants and Refugees in September, he noted the new troubles brought by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The precariousness that we have come to experience as a result of this pandemic is a constant in the lives of displaced people,” he said.

]]>At the same time, the person elected as president of the United States, traditionally a role that has served as broker between warring parties, was elected on an “America First” stance.

Needless to say, the world needs more peace makers. The United Nations is one organization that tries to fill the void; it currently maintains 14 different peace keeping operations, and mediates negotiations for many other conflicts. Anjali Dayal, Ph.D., an assistant professor of political science, says that as flawed as the U.N. is, it’s still an absolutely necessary bulwark against spreading chaos.

Full transcript below

Anjali Dayal: We live in a world where the dominant idea about peacekeeping is that it fails, is that it doesn’t work that well, and that the UN is sort of a paper tiger. That turns out to not actually be the case.

Patrick Verel: In 2016, more countries experienced violent conflict at any time in the previous 30 years. From Yemen, Syria, and Venezuela to Myanmar, the democratic Republic of Congo, and Ukraine, violence has become a more common answer to resolving disputes. And one of the consequences has been that more people are displaced around the globe than any time since World War II. At the same time, the person elected as president of the United States, traditionally a role that has served as broker between warring parties, was elected on an America-first stance.

Needless to say, the world needs more peacemakers. The United Nations is one organization that tries to fill the void. It currently maintains 14 different peacekeeping operations and mediates negotiations for many other conflicts. Anjali Dayal, an assistant professor of political science at Fordham, says that as flawed as the UN is, it’s still an absolutely necessary bulwark against spreading chaos. I’m Patrick Verel and this is Fordham News.

In June, the United Nations estimated that nearly 71 million people were displaced around the world by the end of 2018. What’s going on?

AD: Conflict in three countries is the primary driver of the refugee crisis, according to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees. Conflict in South Sudan, Afghanistan, and Syria is responsible for nearly 60% of all refugee displacement in the world right now. This is really the most protracted refugee crisis that we’ve seen since the institutions that we have in place today were put in place at the end of World War II. It’s such a protracted crisis that it’s actually fundamentally remaking the domestic politics of host countries and potential host countries. You started out by talking about the America-first policy, US domestic politics is being reformulated in response to migration across the Southern border. Migration that’s driven by the legacies of conflict, migration that’s driven by climate change, migration that’s being driven by people desperate to flee crime and lack of economic opportunity.

Countries that have hosted the most refugees are usually neighboring countries. When we talk about like displacement from the Syrian crisis, for example, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey host most Syrian refugees. Lebanon has huge number of refugees in proportion to its domestic population. But it’s also a question further afield. In 2015 and 2016, people often talked about this as the European refugee crisis, even though very few in comparison refugees actually ever made it to Europe.

All of this is alongside the sort of important research that political scientists have done, and historians, and economists demonstrate that refugees are not huge drivers of crime. And so when we think about these kinds of crises, we’re talking about multiple compound humanitarian crises, systems that are strained to their breaking point in terms of being able to manage, process, and resettle refugees, countries that are not particularly willing to resettle refugees just as the crisis becomes most acute, and sometimes generational displacement, so people who are born into multiply displaced communities.

PV: Talk to me about the United Nations Security Council. Now, since Russia went along with a no fly zone resolution over Libya that the council passed in 2011, Vladimir Putin has since said it was a big mistake. Does this make it unlikely that the Security Council will ever back serious peacekeeping operations?

AD: In order to get a peacekeeping mission, you need a Security Council authorization. There are five permanent members of the Security Council, the UK, the US, Russia, China, and France. Any one of those permanent five members can unilaterally veto a mission. We only see peacekeeping missions in the world where no member of the P5 has a reason to veto.

What we end up seeing is a system in which cases where the permanent five members of the Security Council don’t have a really strong vested interest in the outcome of a conflict, they’re the ones that get peacekeeping mission. Now, we started about talking about the refugee crisis. Obviously, that’s a huge problem when we think about the number of refugees the Syrian conflict is generating. But this is a political set of calculations. It’s a disagreement about what Syria should look like between the permanent five members of the Security Council, so we’re not going to see mission there.

The Libya case is really interesting, because that is a case where Russia and China both abstained from the decision. They didn’t veto it. In retrospect, both, or Russia at least, has noted that they felt it was a mistake, that it was opening the door to greater action than was initially requested. That sort of exemplifies those dynamics. When they thought it was a more constrained mission that was not involved in regime change but for protection of a particular population, they were onboard with it, as they seem to be on board with other missions where they have fewer interests. When it became what they considered to be a regime-change endeavor, that’s something they’re uncomfortable with.

What we see in the world today is that we’ve got 14 missions where the P5 agreed pretty well. The problem is those fracture points, disagreements on Ukraine, on Syria, on the aftermath of what happened in Libya, those could actually fray the consensus that we have for other cases.

PV: Now, you wrote a book about why combatants and civil wars engage in the UN-led negotiations, even when they believe the UN is a failed flawed contributor to the peace process. I believe that was your term.

AD: Yes.

PV: What did you find?

AD: Yeah, so at the book manuscript is under review right now. The basic question that I had was the theory, the way we think about peacekeeping today, is that peacekeepers work to solve a security problem. They are usually, or traditionally they were sent out after the signing of a peace agreement. The important thing that they do in that situation is to help uphold the terms of the agreement. You don’t have to trust the other side to uphold their end of the agreement, you just have to trust the UN to be able to help you uphold the agreement. In a world where you’ve been willing to kill each other over something very recently, right, that’s a really valuable resource. Having someone help calm incredibly neutrally uphold your agreement, having them help you disarm, having them help you demobilize, having them provide you information about the intentions and the actions of your phone or opponents so that small accidents don’t spiral back into big, full-scale war again. Right? That’s a really critical set of things that the UN can help do, that UN peacekeepers can help do.

But in order for peacekeeping to actually work like that, people have to believe that the UN can credibly and neutrally uphold the terms of the agreement. We live in a world where the dominant idea about peacekeeping is that it fails, is that it doesn’t work that well, and that the UN is sort of a paper tiger. That turns out to not actually be the case. Right? It turns out that depending on how you count, UN peacekeeping missions are incredibly successful at upholding agreements. There’s a failure rate of about like one out of every four. You’re talking about three out of four cases of conflict. That’s not a bad success rate.

That isn’t the way we think about it though, because that fourth case is still important. The one that fails, people die, people lose their lives and it generates lots of news coverage. Then the question becomes what do they want the UN for? If they don’t think the UN is going to protect them, why are peacekeepers on the ground for them? The answer that I have is because there’s a full range of other things that UN peacekeepers do that are not actually related to security.

The presence of UN peacekeepers on the ground can bring you material benefits, it can bring your tactical benefits, and it can bring you symbolic benefits. If we start with material benefits, peacekeepers arrive and they infuse goods and services into the economy. You could have tactical benefit. If you really believe that the UN is not going to help you uphold your agreement, then you could use the time that they’re there to regroup or rearm, right? You could use the time that they’re there to help launch a counter attack. The last thing you could get is a set of really important symbolic and legitimacy benefits. Sitting down with the UN, inviting the UN to come help oversee your agreement, hosting UN peacekeeping mission, that’s a really good way to demonstrate to your former opponents, to the citizens in your country, to the larger world that you are genuinely invested in the peace.

PV: What’s the gold standard for peacekeeping mission in your mind?

AD: That’s a really good question. There are some big successes that people talk about, peacekeeping missions in Namibia, in Mozambique, in East Timor, interpositional peacekeeping missions, so peacekeeping missions between two countries as opposed to within a country. Lebanon, for example. That one’s a little more contentious today. But those are all missions that have in the long run prevented backsliding into war.

Much like the discussion about what counts as a failure, the question of what counts as success is loaded for a lot of people. For most peacekeeping scholars, it’s about five years without sliding back into war, which is not an insignificant accomplishment. But we should note that that doesn’t mean that peacekeepers leave behind a vibrant democracy where everyone is equal and flourishing. It just means there’s no war.

PV: Why are women key to diffusing conflict?

AD: At most, 3% of negotiators in peace processes are women. 97% of negotiators are men. Participants, it’s a similar divide. We see very few women in the room for peace agreements. Even though we don’t want to make a centralist arguments, that actually has real, and critical, and negative effects in the world. More inclusive peace agreements are more likely to last. The more people you have in a room reenvisioning the nature of the post-conflict state, the more likely you are to actually see an agreement that can actually produce a stable state afterwards.

There’s a trade off that negotiators sometimes make. They think, can we get these people to stop shooting each other? Right? Then can we arrive at a transformed society with a post-conflict vision of the peace to keep this from happening again? It really matters that half the society is shut out of a room. Especially because the concerns that women ring that are gendered are not irrelevant to the peace. There are things like local security. How easy is it to go get water at night in a dimly lit space or in a space with no light? How safe do you feel walking around? What is the likelihood that you are going to experience sexual abuse or exploitation in your lifetime? Right?

PV: I just want to come back to one particular number that really stood out when you said that. 97%?

AD: Yeah. These are UN statistics.

PV: That’s bonkers.

AD: It’s crazy. It’s absolutely crazy when people talk about like women in peace processes, I don’t think people really know that that’s the breakdown, right? Like, it is that extraordinarily male, the peacemaking space.

PV: So, it’s just assumed that the men would just know everything that’s going on with all the women in their live’s lives that they’re going to speak on behalf of them?

AD: Well, one of the things we see that’s really interesting is that there’s a journal article I have forthcoming in the Journal of Global Governance with my coauthor Agathe Christien who is a research fellow at the Institute For Women Peace and Security at Georgetown. We look at informal peace processes, like what people often broadly group as being like track two diplomatic initiatives, informal women’s movements for peace, informal women’s groups for peace, and it turns out women dominate the informal peacemaking space.

We looked at 63 different peace processes. Most of those processes we can identify a distinct set of women’s groups that are advocating for the peace. That we see that tells us something about the way these sort of axes of negotiation are separated, but it really also tells us that there is space for the formal peacemaking world to open up. The way it is now is almost like a throwback to like old diplomatic traditions. Women have been informally making peace for as long as there have been male diplomats in the world. Whether we think about like queen consorts or we think about like diplomats wives going out and hosting dinners, right?

PV: Isn’t there a story from the Greek times of women withholding sex to get the men to stop from fighting or something?

AD: Yeah, the Lysistrata?

PV: Yeah. That’s it. Yeah.

AD: Yeah, so like, women’s informal action to force a peace is like common. When we think about Lysistrata, we also think about like women in Liberia being incredibly active to try and force the formal parties to conflict into a negotiation statue. They surround the hotel, they say “You’re not coming out until you come out with a peace agreement.” Right? It’s this kind of informal action that demonstrates that even people who are shut out of formal processes are not passive in the face of their exclusion. They want inclusion.

PV: This is a topic that is not inherently a positive one. We’ve talked a lot about all of the death, and displacement, and conflict in general. What gives you hope?

AD: I think a lot about Rebecca Solnit’s work, in particular Hope in the Dark. She writes, “Hope is not a lottery ticket that you sit down on the sofa with and wait for something to happen. Hope is an axe, and you use it to break down what stands in your way.” For me, what gives me hope is seeing, even despite how difficult some of these issues are, how committed some people are to solving them. I spent a lot of time as a kid watching Sesame Street and Mr. Rogers. Often in crisis moments, people turn back to Mr. Rogers, look at the helpers, right? That sort of idea of what should-

PV: Oh, wow. Yeah.

AD: Yeah, exactly. What should you tell children when something is really difficult? You tell them to look for the people who are trying to help. I think that’s true for adults, also. Not just to see that people who would like to change things exist in the world, but that you can become one of them. Right? That it’s not an insurmountable barrier.

The other thing we might think about is, I think it’s a Talmudic set of expressions, right, that you aren’t obligated to alleviate all of the world’s suffering, right? But that doesn’t absolve you from taking up any of the task. One of the ways we’ve seen that is with the Youth Climate Movement. That’s the source of a lot of hope, I think, to a lot of people. It’s a troubling source of hope because it is children getting up and saying to us like, “We’re desperate. We need you to do something.” But it is instructive to see that mass movements like that can build, right?

Something like climate change, individual action can’t help us resolve that. That’s also the case for things like violent conflict or a refugee crisis. But enough individual decisions to participate in pressuring governments and holding them to account demonstrates that these are issues of importance to people. Right? If we can get in this space of a year, a Children’s Youth Climate Movement to come and shut down cities or to come and make sure people are aware that children everywhere invested in this issue, right? That isn’t a straight success, but it is a hopeful thing. It’s the kind of thing that just says, “Okay, this is an axe. We can use it. We can use it to break down apathy. We can use it to break down the kind of avarice and the kind of greed that can keep us from arriving at collective solutions to problems.”

]]>“Universities are challenged in an urgent way by the questions that are now posed, questions that are after all existential, that are of the survival of the biosphere, of deepening inequality, of a return to the language of hate, war, and fear, and the very use of such science and technology yet again for warfare rather than in serving humanity,” he said.

The Sept. 30 lecture was part of the Ireland at Fordham Humanitarian Lecture Series, a partnership between the Permanent Mission of Ireland to the United Nations and Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs. (Watch the full lecture here.)

Higgins, a poet and former professor, said the Irish lost at least one million lives to starvation during the Great Potato Famine and saw more than 2.5 million emigrate. Therefore, the nation holds a collective memory that resonates with today’s crisis.

“We have known what it is to be hungry,” he said in his lecture, “Humanitarianism and the Public Intellectual in Times of Crisis.”

He noted that the Irish famine was editorialized in some newspapers as “an act of God.” The difference today, he said, is that the constant drumbeat of the news cycle desensitizes the listener.

“[Today,] we’ve become accustomed to narratives of how men and women throughout the world as refugees find themselves, through extended periods of time in unsuitable accommodation, confined to forced idleness, without even control over their daily diet,” he said.

Eugene Quinn, director of the Jesuit Refugee Service in Ireland, he noted, has said that children grow up “without the memory of their parents cooking a family meal.”

He lamented that millions of refugees spend years stranded in semipermanent camps around the world, while world leaders discuss the “internationalism and interdependency” of international trade.

“In fact [the conversation]nearly always begins with trade. This has devalued everything, really, in relation to intellectual life, and it has devalued diplomacy very seriously.”

He said that people’s loss of citizenship is so much more than a loss of a homeland. The rights of displaced humans become distinct from the rights of “the citizen.” Without citizenship, refugees lose their inalienable rights as a person, as well as their voice, he said, referencing Arendt.

“To be stripped of citizenship is to be stripped of words, to fall to a state of utter vulnerability with avenues of participation closed off, and thus new futures disallowed,” he said.

Given their past, he said that it falls to the Irish, at home and abroad, to be exemplary to those seeking shelter, especially since it is a crisis that will continue, fostered by climate change and exacerbated by precarious political situations.

“This is a deepening, if you like, of what I call the intersecting crisis of ecology, economy, and society,” he said.

But unlike the welcome that many European refugees received in the wake of World War II, today’s refugees have been shunned.

“The relatively small number of refugees reaching our borders [in the West] has brought forth the type of narrative about ‘the other’ that we in the humanitarian tradition had hoped was assigned to the chronicles of the past,” he said.

“Countries whose citizens have often benefited from international asylum and migratory flows are reneging on their commitments with the aim of discouraging or inhibiting refugees from seeking the international protection to which they are entitled.”

It is here, he said, that public intellectuals and universities must play a crucial role to alter a discourse “soured by hateful rhetoric.” However, he added that today’s charged atmosphere has not made it easier for the academy to exert influence, with some in the community seduced by corporate power, and others complacent with current economic models as the only way forward, he said.

He asked what is being taught in Economics 101 in North America, and questioned how much of it was game theory and how much was real political economy, to say nothing of the coursework’s moral content. He worried that an emphasis on funding beyond the state has had a disjointed effect on the career structure of young scholars.

“I believe public intellectuals have an ethical obligation as an educated elite to take a stand against the increasingly aggressive orthodoxies and discourse of the marketplace that have permeated all aspects of life, including within academia,” he said.

Edward Said said it best when he stated that an intellectual’s mission in life is to advance human freedom and knowledge, he said.

“This mission often means standing outside of society and its institutions and actively disturbing the status quo. Yet it also involves placing a strong emphasis on intellectual rigor and ideas, while ensuring that governing authorities and international intermediary organizations are well-resourced. To quote Immanuel Kant, ‘Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind.’”

For World Refugee Day on June 20, the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) is asking everyone to “take a step” in solidarity with refugees. The campaign challenges people and communities to show their support in fun, active, ways—like dancing, running, or biking—and post to social media to encourage others to do the same. Other ways to get involved include attending a World Refugee Day Event, hiring and welcoming refugees, and reading and sharing their stories.

Fordham took a step with refugees last fall when the University signed on to the #WithRefugees campaign, joining a coalition of more than 500 universities, businesses, foundations, faith-based organizations, youth groups, and NGOs who are working together to provide help and support to refugees and asylum seekers.

“We live in a world in which millions of refugees—many of them children—have been driven from their homes by war, ethnic strife, and natural disasters,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “While society is a long way from addressing the root causes of the refugee issue, we can, and must, do our utmost to care for those whose lives have been violently uprooted. To do so is a duty we owe every single member of the human family.”

Fordham has recently hosted several events focused on the struggles of refugees, including a conference on women who are forced to flee their homes and a panel on leadership needed for this global crisis.

More information about how to get involved can be found on the UNHCR’s World Refugee Day website.

]]>

A thousand delegates from Catholic schools across the world congregated at the Lincoln Center campus and nearby locations for the World Congress of Catholic Education, hosted by Fordham from June 5 to 8.

“I cannot overestimate the importance of a Catholic education and your work in bringing that gift to the widest audience possible,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, in his welcome message. “The schools and educators you represent do holy work every day, and in that work, they transform the lives of young people around the globe. Those young people in turn change the world.”

The four-day conference, sponsored by the Graduate School of Education’s Center for Catholic School Leadership and the Office of International Catholic Education, examined global education issues in collaboration with bishops, universities, and religious congregations throughout the world.

At this year’s conference, delegates representing more than 85 countries and 200,000 Catholic schools were present. Several years ago, Gerald M. Cattaro, Ed.D., executive director of the Center for Catholic School Leadership and Faith-Based Education, led the U.S. delegation at the 2015 World Congress in Rome.

“The world conference of Catholic education presented Catholic education at its best as a gift to all nations,” Cattaro said. “This year, we gathered at Fordham to share our vision for the future: to provide sustainable Catholic education, modeling the pedagogy of Pope Francis—pedagogy of heart, hands, and mind in an effort to better serve the marginalized, the poor, refugees, and those on the peripherals. In other words, to teach as Jesus did.”

The conference began with a 5:30 p.m. opening Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, attended by Archbishop Christophe Pierre, apostolic nuncio to the United States; Father McShane; and several other clergy and faith leaders. Over the next two days, the guests attended lectures and panels presented by key figures in education, including Marc Brackett, director of the Yale University Center for Emotional Intelligence, and Agbonkhianmeghe Orobator, S.J., president of the Jesuit Conference of Africa and Madagascar. Archbishop Angelo Vincenzo Zani, secretary of the Vatican Congregation of Catholic Education, presided over all the conference events.

Guests were invited to attend eight available “labs,” where guest speakers discussed their innovative teaching methods. Topics included creating more inclusive schools and protecting children against abuse. To accommodate all of the international guests, each lab topic was presented in English, Spanish, and French.

A Crisis of Compassion

One of the first labs, “For a new format of education, adapted to change, and grounded in a culture of dialogue,” featured TED Talk speaker Kiran Bir Sethi, Ph.D., the founder of an internationally-recognized teaching strategy, and Kari Flornes, Ph.D., a Norwegian philosophy professor who spoke about the importance of teaching empathic communication to children.

“For 15 years of our children’s lives in schooling, we tell them that their education will be incomplete if they do not learn about photosynthesis, quadratic equations, the height of Mount Everest, or even grammar,” said Kiran Bir Sethi, who founded the Riverside School in Ahmedabad, India, in 2001. “But in those same 15 years, we struggle with finding the time to get our children to care about inequality or child rights or compassion … or even love.”

Sethi’s solution is a four-step formula—FIDS (feel, imagine, do, share) for kids—that taps into children’s creativity, compassion, problem-solving skills, and collaboration. It is currently used in more than 65 countries to encourage students to solve local challenges like bullying, she said.

“We ask them to actually go in teams to implement the solution. And finally, we ask them to share—we ask them to share their story of change with the world to inspire others to say, ‘I can’ [too].”

In 2017, Sethi met Pope Francis in Vatican City and signed an agreement that introduced FIDS and her global movement, Design for Change, to more than 460,000 Catholic schools across the world.

The second speaker, Karni Flornes, an associate professor at Bergen University College in Norway, emphasized the importance of educators using empathetic communication in their classrooms.

Aspects of empathetic communication include teaching non-violence and no-hate speech in all subjects, speaking about controversial issues in the classroom, and actively coexisting with people who look different from themselves.

“[Children] have to practice dialogue between people of different views and learn it’s possible to live with diverse opinions,” Flornes said. “It’s not always possible to reach consensus. But it’s possible to live together without violence.”

She said that parents can also use empathic communication by seeing and following their children’s initiatives, sharing their personal experiences with them, and giving praise and showing recognition.

Sharing Global Ideas at the United Nations

The World Congress of Catholic Education conference culminated with a Saturday morning convocation and program at the United Nations general assembly, moderated by Cattaro.

In his introductory remarks, Archbishop Bernardito C. Auza, the Holy See’s permanent observer to the United Nations, said that society needs to be based on “humanism”—a concept that starts at home with the family. Educators must bolster that idea by building spiritual values in students, he said.

Later, a global panel of leaders presented problems and solutions in their native countries, including how to effectively teach sustainability in classrooms and educate students in local prisons. Jaime Palacio, a lay missionary from Peru, spoke about the challenges of educating children in the Amazon. Educators need to listen to the needs of the Amazon community, he said, and help them defend their land and culture. Another panelist—Jose Arellano, executive director of the Catholic Educational Association of the Philippines—considered ISIS’s recruitment of uneducated Muslim children in Asia. One way to prevent this is peacebuilding through education, he said, like the Madaris Volunteer Program in the Philippines.

In a video message played at the United Nations, Pope Francis also addressed conference participants. For 12 minutes, he spoke about the future work of Catholic schools, expressed his gratitude toward Catholic school educators, and greeted the millions of students who study in Catholic schools worldwide.

“Young people, as I said at World Youth Day in Panama, belong to the ‘today’ of God,” Pope Francis said, “and therefore are also the today of our educational mission.”

— Jeanine Genauer contributed reporting.

[doptg id=”149″] ]]>The group’s diversity reflected that of the United Nations. Members hailed from Brazil, Ghana, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and nearby Orange County. Most of them had already entered the working world: Three were on leave from their jobs at the city’s Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), one was taking time away from her position as a case manager at an independent living center for people with disabilities, and a third was currently working with immigrant students at a Washington Heights nonprofit.

As part of their participation in the U.N. student group, they each held internships at nongovernment organizations that are affiliated with the U.N., including the International Federation of Social Workers; the Unitarian Universalists; the Public-Private Alliance Foundation; and Close the Gap, an NGO bringing technology to remote areas of the world.

Collaborating Over Coffee

These café meetings provided the group with an informal way to talk about their work, support each other, and even rib each other a little.

“It’s pretty easy-going. There are a few running jokes and some teasing,” student Alessandro Guimaraes said of the early-morning sessions.

“A lot of things come up. When they needed two more people to present at a conference, (classmate) Taylor and I volunteered. When it comes to work there’s always more than enough people to speak about the issues we each work on. If we can’t speak then on something, we’ll help do the research.”

In the weeks that followed, the students sat in on several U.N. committees and related events, including a presentation of the rights of indigenous peoples, a meeting of the Committee on Migration, and the Women’s Institute Conference. They presented research to the American Psychological Association, at the Commission on the Status of Women, and organized several conferences and panels of their own. Between their NGO internships and their additional time at the U.N. itself, they far exceeded the 21 weekly hours required to complete their second year’s fieldwork requirement.

Guidance from a Celebrated Social Work Educator

In the café, beneath a map of the world, Elaine Congress, D.S.W., a longtime associate dean at GSS and a respected stalwart in the field of social work, observed her students as they bonded over program she directs.

Hers is a well-known name in social work circles. Debra McPhee, Ph.D., dean of GSS, once said of Congress:

“There isn’t anybody in the profession who doesn’t know Elaine. The two most common questions we get are ‘Do you have a Ph.D. program?’ and ‘Is Elaine Congress still teaching there?’”

Congress said that the morning meetings help counterbalance the formality of the U.N. Similarly, she said the program came into being rather informally as well.

“The person that had been chair of the international committee for New York City’s National Association of Social Workers and the main representative for the International Federation of Social Workers said to me, ‘Would you like to represent the NGO at the U.N?’” she recalled. “That’s how I started working with these NGOs.”

Almost immediately on her arrival, she began getting her students involved, first in assisting IFSW, and later at other NGOs internships she arranged

Around her, the students swapped stories from their day jobs and outlined plans for future conferences that they were organizing. The initial levity gave way to serious moments when they discussed what they’d heard in their various committee meetings.

For Guimaraes, the statistics can be shocking—“whether we’re talking about violence against women or indigenous people being taken from their lands,” he said. “We’re human and we have emotional reactions, but a lot of times you become used to hearing those things and it’s not as shocking. But that’s why we’re here to do the work.”

As the meeting ended, Congress watched her students fan out to their various committee meetings.

“These are the future social worker leaders in our city, in our country, in our world,” she said.

An American Immigrant Helping Immigrants

When Guimaraes walks the halls of Gregorio Luperon High School for Science and Mathematics in Washington Heights, teens give him a hand slap and a half hug. He serves as a counselor at the school, which is the setting of a second concurrent GSS field placement, one that is more people-focused than his U.N. work. Spanish is spoken everywhere in the halls. Guimaraes talks about the kids as they pass him: “He’s on the chess team. … We stared the school newspaper with him. … She’s on our drum team.”

One student stops him and asks, “What’s that test you were talking about? The P-something?”

“The PSAT,” he answers. “Give me a second, I’ll get you the form.”

He explains to a visitor that the high school is for students who have been in the country for less than four years. Most are from the Dominican Republic, where the schools are often at capacity and lacking in quality, he said. After Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, the school saw an uptick of students from there, but most of the students don’t arrive with an American passport. There were a few migrants from El Salvador. Recently, there was a student admitted from Venezuela. She hadn’t eaten for four days before arriving.

Guimaraes can relate to these kids. He left Brazil when he was a teen to live with his father in the U.S. He didn’t speak English and he struggled.

“I had my own experience going through changes—changing country, changing education. I was a pretty bad student in Brazil because I didn’t have anything that I knew I wanted to work toward,” he said. “When my dad asked if I wanted to come I said, ‘What the hell do I have to lose?’”

Guimaraes acknowledged that his challenges were not as difficult as those faced by immigrant students in Northern Manhattan. But his past remains part of the reason he wants to work on problems created by migration. It’s also why he likes his full-time job with Fresh Youth Initiatives, a community-based organization (CBO) that helps immigrant children navigate grade school and high school, as well as prepare for college. The job sprang from his first-year placement. He liked it too much to leave, so this year he began working there full time and takes his GSS classes on the weekends.

“I am just trying to figure out, how can people have opportunities that might spark that interest in them. The more challenges you have to go through, the less likely you’re going to have that opportunity. I’m just trying to be the bridge between those different worlds. That’s what I want to do,” he said.

Global Informing Local

Guimaraes said his work at the school is informed by his U.N. placement, which is with the International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW), where he chose to focus on the Committee on Migration and its subcommittee on Migrant and Refugee Children.

The dual placements allow him to see the micro practice at the local level and hear the macro approach of policy at the global level. The two go hand-in-hand, he said.

He’s appreciated getting the global perspective, but he’s noted that bloated bureaucracies can stymie getting things done at the local level.

“We know what we have to do: We have to open up access for people to get quality education, get health care, all that kind of stuff, and preserve their basic human rights of being able to move if they have to.”

But approval processes are complex and implantation of new ideas can prove difficult. And the recent uptick of anti-immigrant rhetoric in the U.S. hasn’t helped, he said.

“The students I see may be a little bit behind, may need a little bit more time and resources before they can contribute to society, pay taxes, all of that,” he said. “But all of it just has to do with that welcoming piece. In the United States, the people with this point of view are not the ones who are in government now and so they’re turning other people away.”

And though he’s appreciated watching international policy develop at the U.N., he thinks he wants to continue to work at the local level.

“I haven’t found myself with enough motivation to leave clinical practice entirely, because while we have to think globally and advocate for global issues, the work has to be done locally,” he said. “If you can connect with communities, engage community-based organizations, the public-school system, politicians, stuff like that, on a community level, you’re able to slowly take it up a level, even as far as the U.N.”

Valentine’s Day

A month passes; the students have continued to meet every week at the café near the U.N., which Congress has come to call her office. It’s Valentine’s Day and one of the students is passing out chocolate hearts. Another is getting teased for his constant attempts to delegate work.

Yasarina Almanzar smiles knowingly. Almanzar also works for ACS; she deals directly with the children and their families when the court finds her supervision necessary. Like her colleagues, she’s been given leave and a partial scholarship to get her master’s at Fordham.

Two days a week she goes to her U.N. internship at the Unitarian Universalist Office of the United Nations. There she focuses on different social justice issues. She’s been working with other interns to organize a three-day seminar focused on equality. As part of her research for the conference, she met the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, a human rights expert appointed by the U.N.’s Human Rights Council.

“I’m not really exposed to that kind of work at ACS, things like policy work and how you go about bringing a change,” she said. “It helps my work at ACS, because we have a lot of children of color, it’s important to understand the work that’s being done internationally.”

As an immigrant herself—she arrived from the Dominican Republic when she was 12––Almanzar has experienced racial bias first hand.

“As a woman of color, I see the differences in treatment I get,” she said. “And in terms of my clients, who are people of color that have needs, understanding how to advocate for them becomes a great cause.”

Advocating for Others Who Don’t Look Like You

Almanzar’s lived experience as a woman of color contrasts sharply with Guimaraes’ experience as a white man. She can go into a community as a part of the community. Whether one is advocating on behalf of a community-based organization or an NGO, it helps to look like the people you’re representing, said Guimaraes.

“Coming here from Brazil at the age of 14, without any English, I couldn’t really identify myself with white Americans, even though I was white,” he said. “I’ve always tried to be aware of the historical context of how my family ended up in Brazil, how I ended up here, how people move around the globe.”

He said that most of his family fled World War I from Europe and emigrated to São Paulo. Growing up, he was taught to go after what he wanted. But he realizes it’s not that easy for everyone.

“I try to acknowledge that as a cisgendered white male, you get pushed forward more than other people.”

Another great concern of Guimaraes is for the welfare of native peoples. As part of his U.N. practicum, he has served as assistant secretary to the NGO Committee on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. There he quietly takes down the minutes for the meetings and streams them live on Facebook.

He has been told by a professor to be aware that research differs greatly from lived experiences, and as a social work professional, he needs to be aware of that.

“Yes, you can be an ally, but it’s important to recognize that someone with experience is the expert,” he said. “To the immigration experience, I can say that I lived through it. I can speak to it. To being indigenous, I can’t.”

He tries to teach his students at the high school to engage in the global conversation so they can represent themselves. He even helped one student become a youth representative to an NGO at the U.N.

“If I can teach them how to speak for themselves, or use maybe the privileges or the platform that I have to get them to be better represented, then I think that’s a good thing,” he said.

Roberto Borrero, chair of the NGO Committee on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, said sitting in on subcommittee meetings opens up a new world view for social work students, regardless of their background.

“There’s different types of learning, there’s learning you get at the University, there’s various tasks that you have to get your accreditation, but it’s different when you participate in meetings where there’s different levels of bureaucracy and you learn to engage,” said Borrero.

On Language

As most of the students have worked for large municipalities, they are familiar with the language of local government and the many acronyms used by its agencies. For example, Guimaraes works for a CBO at the DOE while interning in an NGO at the U.N. Likewise, Almanzar works at ACS serving mostly POC communities. The U.N. and it’s NGOs present yet another set of acronyms and nuanced language use.

“The students are here and witnessing how things work,” said Borrero. “They hear U.N. folks come in, how they talk, the terminology that they use, it might not be the same terminology that they hear in their specific field, but again this has expanded their mind to it.”

A Careful Introduction

By mid-March the students had attended at least a dozen subcommittee meetings between them. When the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) convened at the U.N., 400 related panels were held around the city.

The students each presented individually on underrepresented women in a panel titled “Shining a Light on Forgotten Women.”

Indeed, Guimaraes began his presentation on indigenous women with a precise series of caveats, acknowledging his white cisgendered male identity and warning listeners that some of the violence he was about to discuss might trigger people in the audience who had experienced similar trauma. And he shouted out all the women who played a role in his success.

“Thank you to the women in the room, the women in my life, and the women in leadership that helped me speak to you today,” he said.

A Rigorous Fieldwork Program

Outside Elaine Congress’ office sits a hopeful student seeking to get into the United Nations program she runs for next year. The student sits quietly, while within earshot Congress explains the program requirements to a visitor in her office.

“We require 21 hours a week for field placements. I take only leadership students, because there aren’t any clients, unless you count nations as clients,” explained Congress.

GSS students have to complete two field practicums: a generalist placement, which exposes students to foundational social work practice, and a specialist placement during the advanced year. In the generalist field practicum, the goal is to expand students’ social work practice experience with populations that are new to them. During the specialist year, students are assigned field placements in their preferred areas of practice, working with more complex client populations and settings. All of Congress’ students are on a leadership track.

With 10 books behind her, Congress is recognized as an expert on many aspects of the discipline, but on multiculturalism in particular. She is working on the fourth edition of widely referenced Multicultural Perspectives in Working with Families (Springer, 2013). And she is the recipient of dozens of awards, including a lifetime achievement award from the New York City chapter of the National Association of Social Workers.

Congress said she has always been interested in social justice work. She worked in a mental health clinic in Brooklyn with the Latino community before getting her doctorate moving toward academia.

“I was always concerned about the poor and I was also very interested in people from different backgrounds,” she said. “Then I came to Fordham, and progressed on up through the ranks from assistant to associate professor to associate dean, and I started to write.”

Self-Assessment is Critical

On listening to Congress, one can begin to see the influence she has on her students. As an educated white woman, she said, she too needs to understand where she comes from to help people with backgrounds distinct from her own.

“It’s very important to do a self-assessment even before you begin to work with clients,” she said. “You have to know about who you are before you work with others.”

And, she said, collaboration amongst social workers is key. That’s why she insists on those morning meetings.

“Issues come up all the time. It could be a current event issue. It could be an event at the UN. We talk about all of it. It’s education. It’s also supportive,” she said.

She bid her visitor goodbye and welcomed the waiting student into her office.

Building Strong Bonds

The bonds formed by these students over the course of the semester are palpable to even the casual observer. They’re fans of each other’s work and offer support at every turn.

When MSW candidate Taylor DeClerck, a case manager at an independent living center for people with disabilities from Orange County, had to present with the group in the city at 8 a.m. on a Saturday, fellow student Abigail Asper put her up for the night.

And the group was uniformly impressed by student Melissa Cueto’s presentation on elderly women at the “Forgotten Women” panel on March 14.

“She is such a great public speaker and she works at ACS too, but I never had an opportunity to meet her until I came here. We all learn from each other and we’re always sharing,” said Almanzar, who reached out to Guimaraes for help in forming a panel on indigenous women.

“One of the best things that come from the group is diversity,” said Guimaraes. “We’re all interested in different topics, but we’re all interested in the advancement of human rights. At some point, they all have to do with each other. They all have some commonalities—like us.”

A significant multiyear partnership between the Government of Ireland and Fordham University, the lecture series will begin this month and run until June 2020 with events in New York, Dublin, and Geneva.

The series will consist of a number of distinguished lectures supported by more technical lectures and workshops that are open to all.

“Ireland and Fordham University have deep enduring connections,” said Ambassador Geraldine Byrne Nason, Ireland’s permanent representative to the United Nations. “Our historic ties are rooted in our strong commitments to respect for human dignity and spirit. … As we look toward the humanitarian challenges of the 21st century, such as climate change, gender equality, and ensuring respect for international humanitarian law, I can think of no better partner than Fordham. We believe that a better understanding of these complex issues is critical, as Ireland aspires to make a meaningful difference as a candidate for election to the U.N. Security Council, for 2021-22.”

Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, said the University is honored to take part in the project.

“Fordham is humbled and gratified by the trust that Ireland has placed in the University in creating this grant,” said Father McShane. “The lecture series brings fresh depth to the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs’ mission to educate men and women who are both committed to, and professionally trained in, helping the most vulnerable of our brothers and sisters around the globe.”

Lectures will explore the challenges facing policymakers and humanitarians as they seek to ensure that aid reaches those in need, that humanitarian principles are upheld, and that civilians are protected. Specific topics of discussion will include humanitarian protection through international humanitarian law, humanitarian financing, climate and security, and more.

Brendan Cahill, executive director of the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs, said the new series “complements the overall work of our institute and the leadership in this sector by the Irish government. These lectures and events, by leading U.N., government, and humanitarian leaders, will further inform and provide new insights in providing assistance to the most vulnerable.”

Speakers will include high-level political leaders who will communicate pivotal messages in response to key questions such as: What challenges and opportunities exist in humanitarian action in the 21st century? How do climate and gender drive food insecurity and humanitarian need? And, how can humanitarian action strengthen the role of local actors in humanitarian responses?

The inaugural lecture of the series will be delivered by H.E. Mary Robinson, chair of international NGO The Elders and the first woman elected president of Ireland (1990-1997). She is a former U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights and an advocate for climate justice, gender equality, women’s participation in peace-building, and human dignity. This lecture will take place on Monday, April 29 at 6 p.m. in the United Nations Sputnik Lounge. Learn more and register here.

]]>

“I was persecuted for my sexual orientation, so I came here for a chance at a better life,” said Rosario, wearing a suit and tie. “I could never dress this way or be who I am. I was shamed, couldn’t live my life, and could never sleep. One thing that is ignored is the mental health of asylum seekers and the mental stress they have experienced before [coming here]. It puts you in a shell.”

Rosario was among the asylum seekers who shared their personal stories at Fordham’s “Women and Girls on the Move,” a March 16 event sponsored by the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS) and held in conjunction with the United Nations 63rd Commission on the Status of Women.

The conference, which brought together educators, politicians, social workers, health care providers, lawyers, and students, came at a time when nearly 80 percent of the 68.5 million refugees, asylum seekers, and stateless and displaced persons documented in the last fiscal year are women and young people; 52 percent are children under 18.

Held at Fordham Law School, the conference aimed to shine a light on the intensifying struggles of women and girls who are fleeing their homes in the midst of violence, persecution, and disaster. The organizers hope to use this knowledge to better help others who are also seeking new lives.

And the time for new solutions is now, presenters said. One person is displaced from their home every two seconds, noted Sandy Turner, Ph.D., director of the GSS Institute for Women and Girls, which presented the conference with the International Health Awareness Network (IHAN).

In addressing the U.N. event’s theme—social protections and public services—the conference also highlighted displaced women and girls’ limited access to health care, education, justice, and humanitarian protections throughout the process of migration and resettlement.

“This is about finding solutions to the global migration crisis,” said Sorosh Roshan, M.D., IHAN founder and president.

A panel discussion featured several women, including Rosario, who represented different communities of asylum seekers.

Mahnaz Sarachi, Ph.D., Executive Director of IHAN, said it’s important to understand the different kinds of people in crisis. “Why are they moving?” she said. “They are in search of a better life… they have left their homes to seek safety.”

A Hard Adjustment

Anna Elvira Brodskaya, an LGBTQ and asylum-seeker rights activist, left Russia, where there is a homophobic culture and the LGBTQ community is often victims of violence. In New York, job opportunities were few.

“Women are not perceived as good enough for decent jobs like ones requiring strength,” she said. “You face harassment and you can do nothing about it, because you are undocumented and you have no rights.”

Rosario spoke of how her life here was initially weighed down by locating affordable health insurance, housing, and health care. “Living in New York is expensive, so you might have to live on the street,” she said. “Yes, there are shelters, but they are not always safe.” Now, thankfully, life has improved for Rosario; she has a wife and is writing a book.

Julia Gagliardi, FCRH ’19, of the Social Innovation Collaboratory at Rose Hill, delivered a moving narrative that was created from a collection of stories from resettled students attending colleges and universities in New York City. “On my own, I had to apply for health insurance outside of my university, because I was not eligible, and pay for it at a higher cost,” shared Gagliardi, quoting a student. “On my own, I had to look for ways to finance my tuition, because I was not eligible for financial aid or scholarships. On my own, I had to meet with a lawyer several times a week to apply for a work permit. On my own, I was connected to an independent donor who heard my story and helped fund part of my tuition.”

Ideas and Suggestions

Discussion led to ideas about how universities can create safe spaces.

Brodskaya suggested schools could offer free courses to women new to the U.S. about career options. “They need to be enlightened about the possibilities … they can be employed not just as nannies and cleaners,” she remarked.

Panelists suggested college campuses would be a safe space to learn about U.S. procedures impacting migrants. “Many are now afraid to apply for asylum,” said one.

They also agreed that universities might help the public understand migrants’ lives.

“We could incubate goodwill on campuses,” said Gagliardi, an English and sociology major.

New Challenges

The conference also featured dialogue about what migrants entering the U.S. are facing, including word that the accepted number of refugees entering the country has been lowered.

Frank Kearl, J.D., LAW ’18, spoke of a “walled prison facility” in Dilley, Texas, where migrants are being held in poor conditions.