Molly Bedford and Anthony Hazell, FCLC ’06, stepped down last year as the paper’s visual and editorial advisors, respectively, after seven years. During the annual Block Party reunion, former staff members were presented them with cards, flowers, and framed mock Observer covers featuring group photos and messages from their advisees.

“We had such a special relationship with Molly and Anthony,” said Sophie Partridge-Hicks, FCLC ’21, a former editor-in-chief who helped organize the tribute. “We were there during the pandemic, so we did a lot of Zoom calls, and they were so incredible and supportive of us that we really wanted to celebrate them and all the work they did.”

Courtney Brogle, FCLC ’20, a former managing editor, echoed Partridge-Hicks’s gratitude for the advisors and the rest of the staff.

“The Observer was a real light in a dark tunnel at that time,” said Brogle, who is now an assignment editor at NBC News. “It was a saving grace in a sense, where I got to collaborate with like-minded people. I got to publish student journalism that really mattered as we were navigating an uncertain time. It granted an outlet for people who otherwise would have been very isolated.”

Brogle also credited The Observer not only with setting her on her career path but also providing an opportunity to build personal relationships.

“I met so many people from different walks of life that I consider lifelong friends,” she said. “It brought a lot of joy into my life.”

Hazell, who was the paper’s editor-in-chief during his senior year and is now the director of communications for Bay Ridge Prep in Brooklyn, said that the paper has grown in the past two decades, from 20 to 30 students when he was an undergraduate to about 100 students today.

“I never thought that I would come back almost 10 years later and be involved again, but it was so much fun,” he said. “It was really nice to see the students control the paper and figure things out on their own and help guide them and problem-solve things.”

]]>

Just two days after New York City was blanketed in orange haze due to wildfires in Canada, the air cleared, and on June 9, more than 600 Fordham alumni gathered on the Lincoln Center campus for the annual Block Party reunion in the heart of Manhattan.

Just two days after New York City was blanketed in orange haze due to wildfires in Canada, the air cleared, and on June 9, more than 600 Fordham alumni gathered on the Lincoln Center campus for the annual Block Party reunion in the heart of Manhattan.

“It is an astonishing thing that Fordham has this location at the center of everything,” Fordham President Tania Tetlow told attendees. “The epicenter of the global economy, the center of so much media, of arts and culture, of business, of everything you can imagine.”

The alumni who gathered—from Fordham College at Lincoln Center, the Gabelli School of Business, the Graduate School of Education, the Graduate School of Social Service, and the School of Professional and Continuing Studies—spanned generations and spoke of the lasting impact of their time at Fordham.

“This is a place with many happy memories and a place that really changed my life—my husband, my career, my lifelong friends,” said Karen Ninehan, a teacher and former school principal who earned a bachelor’s degree from Fordham College at Lincoln Center in 1974.

When she decided to go into administration, she returned to campus to earn a master’s degree from the Graduate School of Education in 2000. “I knew this was the place where I would get the best of everything,” she said.

As Ninehan and other guests arrived Friday evening, they had the opportunity to hear some live jazz in Pope Auditorium, thanks to a group made up of two music professors, four students, and Walter Blanding, a tenor saxophonist with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. They attended school- and club-specific receptions across campus before coming together on the plaza for food, drinks, and dancing well into the evening.

Reconnecting with Those Who ‘Helped You on Your Journey’

Margot Reid, GABELLI ’21, said she was especially excited for this year’s celebration—in part because as a member of Fordham’s Young Alumni Committee, she had had a hand in planning it.

“It’s something I look forward to—it’s like a big event of the season,” said Reid, who is a marketing associate as ESPN. “It’s nice to see and connect with everybody.”

Matthew Leone, FCLC ’17, another member of the Young Alumni Committee, was attending his first reunion. “I’m coming back just to find some sense of normalcy again and just to rekindle everything,” said Leone, who finished grad school at American University this spring and is working as an immigration paralegal. “I love seeing this different side of Fordham.”

Harleny Vasquez, GSS ’18, a social work career coach and the founding CEO of yourEVOLVEDmind, was among the featured speakers at the Graduate School of Social Service reception, which highlighted the diverse range of careers and opportunities open to MSW graduates.

“GSS did a wonderful job of teaching us our social work foundation,” said Vasquez, who received the GSS Alumni Service Award in recognition of her work with the school’s graduating students. “You hold the power to utilize your social work degree to design the career you desire.”

For Abigail Brown, Julian Goldstein, and Alice Wong, who bonded more than a decade ago in the Gabelli School’s executive MBA program, Block Party was a chance to reconnect and reminisce about their experiences.

Brown, who graduated in 2014 and now works for General Motors as a future retail development manager, said that she not only enjoys networking with fellow alumni but also catching up with faculty and staff.

“It’s really good to see where people are at, and to connect with old deans and faculty members who helped you on your journey,” she said. “It’s inspiring. That’s the word I always leave here with—inspiring.”

Paying Tribute to Influential Faculty and Advisors

At its alumni reception, Fordham College at Lincoln Center honored two retiring faculty members—English professor Anne Hoffman, Ph.D., and economics professor Janis Barry, Ph.D. Members of the Class of 1973 were inducted as Golden Rams, and there were special shout-outs to the Silver Rams of the Class of 1998 and other graduates celebrating milestone reunions.

“It’s really exciting because it brings back a lot of my classmates, and especially since this is our 20th reunion, we have a really good showing,” said Samara Finn Holland, FCLC ’03, a member of the Fordham University Alumni Association Advisory Board. “I think that makes this year stand out above the rest.”

Nearby, more than 20 alumni who worked on The Observer, the award-winning student newspaper at the Lincoln Center campus, gathered to catch up and honor Molly Bedford and Anthony Hazell, FCLC ’06, who stepped down last year as the paper’s visual and editorial advisors, respectively, after seven years.

And at the Graduate School of Education reception, retiring professor Margo A. Jackson, Ph.D., received the Dr. Kathryn I. Scanlon Award for her service and commitment to the University since 1999.

‘Fordham Was the Difference in Your Life’

This year marked the first Block Party for Fordham President Tania Tetlow, who spoke at various receptions across campus and also addressed a group of the University’s loyal donors at a cocktail reception in Platt Court.

“I love hearing the stories of how many of you feel like Fordham was the difference in your life,” she said, “the investment and opportunity that gave you the launch to everything that you wanted to do, and helped embed the desire in you to matter to the world.”

—Tanya Hunt, Kelly Prinz, and Connor White contributed to this story.

]]>Contrast that with the modern World Cup. Every four years, more than twice as many national teams bring some of the world’s greatest athletes to compete in state-of-the-art stadiums plastered with lucrative advertisements, all watched by millions of fans in person and billions more on screens around the world. (As for the questionable officiating, advanced technology has helped remove at least some human error.)

How we got from there to here is laid out in great detail in The FIFA World Cup: A History of the Planet’s Biggest Sporting Event by Clemente A. Lisi, FCLC ’97. Lisi—who has covered the event as a journalist in places like Johannesburg, Rio de Janeiro, and Moscow—fell in love with soccer as a 6-year-old in 1982, when he was on vacation with his family in Italy as that country’s national team captured the World Cup in Spain. His book, published last month by Rowman & Littlefield, provides a thorough tournament-by-tournament overview, recapping matches, describing on-field trends, and providing the historical and cultural context for each installment. Legends Pelé, Diego Maradona, and Lionel Messi get spotlighted, but the book also tells the stories of the countless other players, coaches, and executives who’ve made the World Cup into the global phenomenon it is today.

How we got from there to here is laid out in great detail in The FIFA World Cup: A History of the Planet’s Biggest Sporting Event by Clemente A. Lisi, FCLC ’97. Lisi—who has covered the event as a journalist in places like Johannesburg, Rio de Janeiro, and Moscow—fell in love with soccer as a 6-year-old in 1982, when he was on vacation with his family in Italy as that country’s national team captured the World Cup in Spain. His book, published last month by Rowman & Littlefield, provides a thorough tournament-by-tournament overview, recapping matches, describing on-field trends, and providing the historical and cultural context for each installment. Legends Pelé, Diego Maradona, and Lionel Messi get spotlighted, but the book also tells the stories of the countless other players, coaches, and executives who’ve made the World Cup into the global phenomenon it is today.

In the process, Lisi, a professor of journalism at the King’s College in New York City (and a former sports editor of The Observer), explores how the World Cup has evolved over the years, not just in terms of the ever-changing format of the tournament itself, but how advances in mass media led to slicker marketing that helped revolutionize the event. Perhaps most significantly, he shows how the tournament exploded in popularity as the sport became increasingly awash in money starting in the 1960s—a phenomenon that has also sometimes led to trouble.

Indeed, the book doesn’t shy away from the World Cup’s many (many) controversies, from the 1934 installment in Mussolini’s Italy to the myriad modern scandals of FIFA, which Lisi calls “one of the most corrupt organizations on the planet.”

This year’s tournament, currently happening in Qatar, unfortunately offers no shortage of material for Lisi, from allegations of bribery during the bidding process, to the loud opposition to holding the organization’s flagship event in a country where homosexuality is illegal, to the mistreatment of the estimated 2 million foreign workers who built the stadiums and infrastructure necessary for the tournament to take place. That the World Cup is happening now, in November and December, is itself a point of controversy: Qatar’s sweltering summer heat necessitated a change in scheduling, disrupting the sport’s usual calendar.

The book ends with a team-by-team preview of the 32 squads competing in Qatar, including a U.S. team that failed to qualify for the tournament four years ago. It also sets up the next chapter (figuratively speaking) in the World Cup’s story: a 2026 tournament jointly hosted by the United States, Mexico, and Canada—one that will feature an expanded group of 48 teams and include matches played in the New York City area, at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey.

—Joe DeLessio, FCLC ’06

]]>The Many Voices Prize was established in June by Elizabeth Stone, Ph.D., the Fordham English professor who also helped establish The Observer itself in 1981 and served as its adviser for 35 years. Carrying a cash award of $1,500, the prize will be awarded with a preference for Observer staffers who are first in their families to attend college or who come from other underrepresented groups.

Stone, a first-generation college graduate herself, believes that journalism has “a kind of moral obligation to be a big table at which everybody could sit.”

The prize is “a way to invite people to the journalistic table,” she said. “The hope is that once they join, they will feel invited, and they will speak what’s on their mind, they will do stories that are on their mind.”

Stone’s gift advances a key priority of Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, the University’s $350 million fundraising campaign, which seeks to reinvest in the entire student experience and foster a more diverse and inclusive Fordham community.

Stone’s gift will fund one Many Voices prize in the coming academic year and eventually three per year. The prize will be awarded for three nonfiction articles or their equivalent published in The Observer, either in print or online, by a staff member. In addition to writing, these works could include video, podcasts, photography, graphic design, graphic texts, cartoons, or other formats that emerge from the evolving media landscape, Stone said.

Alumni Involvement

The prize is coupled with a new effort to advance the career development of Observer staff members by harnessing the connections and expertise of Observer alumni, many of whom got their professional start on the award-winning publication and stay in touch with each other.

An alumni advisory board, formed from the Observer Alumni Affinity Chapter, is being created to advise Student Affairs in awarding the prize and to help connect the paper’s staff members with mentoring, networking, internship, and job opportunities. The board will also help with fundraising to augment the prize, said Anthony Hazell, FCLC ’07, communications director for a K-12 private school and The Observer’s editorial adviser since 2016.

Students for whom the award is meant are often working to meet their college expenses, “so hopefully offering a financial award to make up for the time that they spend on The Observer can help get their voices heard,” said Hazell, who served as the paper’s editor in chief as an undergraduate.

Stone announced the prize June 9 at the annual Block Party celebration at the Lincoln Center campus, saying that a robust diversity of journalistic voices is needed for the survival of our democracy.

The award also reflects her own experiences, she said in an interview. She challenged stereotypes in one of her earliest pieces of journalism, “It’s Still Hard to Grow Up Italian”—published in The New York Times in 1978, it incorporated narratives by several Italian Americans, and much of her early writing was about being the granddaughter of Italian immigrants at a time when, in popular culture, Italians were routinely associated with the mafia.

She hopes the prize will inspire people from underrepresented or misrepresented groups to speak out as well. “What I really hope is that they will speak to who they are, in terms of the subjects that interest them, the politics that interest them, the personal essays that interest them, in the same way that I did.”

Striving for Diversity

Allie Stofer, Observer editor in chief and an incoming senior at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, said she was excited to learn about the award because its cash prize could help students of diverse backgrounds make the time commitment required of Observer staffers. Maddie Sandholm, the managing editor and also an incoming senior at the college, noted that the Observer will also award a new $1,200 scholarship to one of its staff members in the coming year for similar purposes.

She said the paper has been making other diversity-related efforts in recent years, such as relaxing its meeting attendance requirement—to accommodate potential staffers who have conflicts—and hosting workshops on things like keeping biases out of headlines and page layouts.

“The chance to uplift new and underrepresented voices is something that has always and will always be invaluable to The Observer, and so we are honored that Elizabeth Stone … [has established] this prize to support and embody that mission,” Sandholm said.

Working with The Observer was the most engaging part of her job at Fordham to date, Stone said. She fondly recalled the daylong barbecues she hosted for the staff as a sort of retreat, as well as tricky editorial questions that fostered “teachable moments,” she said, “where there was a really vital conversation, and where I was delighted not to be the one who knew everything.”

She is proud to have helped develop and strengthen the paper over the years and hopes the prize will help The Observer stay in step with the anti-racism and multicultural perspectives that are being amplified in the Fordham curriculum.

“I really do believe in a kind of multiculturalism, but to believe in it, you have to see it all around you,” she said. The prize, she said, is “a way of helping to realize that vision.”

To inquire about supporting the Many Voices Prize or another area of the University, please contact Michael Boyd, senior associate vice president for development and university relations, at 212-636-6525 or [email protected]. Learn more about Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, a campaign to reinvest in every aspect of the Fordham student experience.

]]>Our Shared Storm tells the overlapping stories of four characters as they play out in five different future scenarios. Each of the five parts of the book takes place in the year 2054 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s Conference of the Parties—better known as the COP—as a superstorm approaches. The characters’ roles, motivations, and actions differ, though, as a result of how their worlds have dealt or failed to deal with the effects of climate change.

There’s Diya, whose job is different in each story, but who is consistently a power player within the world of climate negotiations. There’s Luis, a Buenos Aires local who exists around the periphery of the conference, from being a driver in one story to a kidnapper in another. There’s Saga, a climate activist (and in one story, a pop star) whose level of pessimism—and comfort—in dealing with government delegates oscillates from part to part. And then there’s Noah, whom Hudson described as his “personal id,” a mid-level U.S. delegate (or, in the same story as pop star Saga, an exploitative entrepreneur) who has limited control over his country’s commitments but who does what he can to grease the diplomatic wheels.

“I got this idea of these four characters and figured out how to sort of remix them each time,” Hudson said. “It’s really fun to do [that], to take your characters and rethink who they are in all these different ways. One thing you can do then is try to find these moments of opportunity and figure out where your characters swerve, and then figure out what that says about the different worlds.”

“I got this idea of these four characters and figured out how to sort of remix them each time,” Hudson said. “It’s really fun to do [that], to take your characters and rethink who they are in all these different ways. One thing you can do then is try to find these moments of opportunity and figure out where your characters swerve, and then figure out what that says about the different worlds.”

In a blurb for Our Shared Storm, the celebrated science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson wrote that Hudson succeeded in finding creative ways to explore those swerves and the worlds that led to them.

“Hudson has found a way,” Robinson wrote, “to strike together the various facets of our climate future, sparking stories that are by turns ingenious, energetic, provocative, and soulful.”

Negotiating the Future

The book’s futures are based on a set of climate-modeling scenarios called the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, or SSPs, which were developed by climate experts in the 2010s and used in the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s sixth assessment report in 2021. The scenarios range from “Sustainability,” in which aggressive climate goals are met and a more utopian future takes shape, to “Middle of the Road,” a continuation of current trends of inequality and consumption, to three more dire possibilities—“Regional Rivalry,” “Inequality,” and “Fossil-Fueled Development”—each of which would bring its own variety of high-level threats.

Hudson came across the SSP framework after starting the master’s degree program in sustainability at Arizona State University’s Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation in 2017 and realized that it laid out scenarios for the future much in the same way that so much speculative fiction does, and in this case, with the explicit backing of scientific research.

“As soon as I read about [the SSPs], I was like, ‘Oh, these are science fiction stories,’” he recalled.

After visiting the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Vienna, which houses the SSP database, and meeting with scholars there to talk further about their research, Hudson realized that by writing five futures set in the same time and place with the same characters, he could eliminate variables and make it a kind of experiment.

“Originally,” he said, “a big part of the way I framed it as a master’s thesis was, ‘I’m going to do practice-based research to analyze my own experience writing these stories and figure out just how hard or easy it is to create literature based on scientific models and rigorous ideas about the climate.’”

Then, in December 2018, a member of his thesis committee at ASU, Sonja Klinsky, arranged for him to be part of the university’s observer delegation at COP24 in Katowice, Poland. Attending the conference, and thinking about the storytelling possibilities of a hypothetical climate event affecting that kind of event, helped him flesh out the book’s structure.

“When I talked with IIASA, we had thought, ‘How does each scenario handle a climate shock?’” Hudson said. “What could show how, [if]a superstorm hits, each scenario handles it differently based on the investments they’ve made?”

In the book, the storm is very strong and causes damage in each scenario, but local and global communities’ ability to deal with that damage—and the levels of suffering and violence that go with it—vary widely.

An Intellectual Journey and a Speculative Movement

Hudson grew up in St. Louis and moved to New York City to enroll at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, where he majored in political science with a minor in creative writing. He also was the opinions editor for the The Observer, the award-winning student newspaper at the Lincoln Center campus.

“The Observer, doing the opinions page, writing a column—all those things definitely were steps on my intellectual journey … of being really keen on stories about arguments,” Hudson said. “And I think discovering that I liked talking to people about their writing was a big discovery that happened there.”

After graduating in 2009, he spent a year working as a journalist in India, where he had studied abroad as a Fordham undergrad, and when he got back to the States, he became a reporter at the St. Louis edition of Patch. From there, he moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, where he did freelance writing and political and nonprofit consulting.

In 2015, Hudson wrote an essay called “On the Political Dimensions of Solarpunk,” which laid out the practical implications of an aesthetic movement that portrays a utopian future in which solar energy is harnessed creatively to build beautiful, sustainable cities and communities. Like the dystopian cyberpunk genre before it, solarpunk is more than just an art movement—it was meant to portray real possibilities for how the world might look in the future.

When trying to define the term in the essay, Hudson wrote, “Let’s tentatively call it a speculative movement: a collaborative effort to imagine and design a world of prosperity, peace, sustainability, and beauty, achievable with what we have from where we are.”

Hudson met, around that time, another writer and futurist thinker, Adam Flynn, who in 2014 had written an essay on solarpunk. The two co-wrote a short story, “Sunshine State,” that won the first Everything Change Climate Fiction Contest sponsored by ASU’s Imagination and Climate Futures Initiative. Seeing the work that was taking place there led Hudson to apply to the university’s sustainability master’s program, from which he graduated in 2020. In addition to his work as a fiction writer, Hudson has stayed on as a fellow at the Center for Science and the Imagination’s Imaginary College, which partners with individuals and groups “advancing [the] mission of fresh, creative, and ambitious thinking about the future.” The college counts Robinson among its resident philosophers, along with other notable writers like Margaret Atwood, Neal Stephenson, and Bruce Sterling.

And while Our Shared Storm began as his master’s thesis, with its publication by Fordham University Press, Hudson hopes that it can help a wider audience see that we still have options for what our climate future will look like.

Science Fiction as an Impetus to Action

While Hudson does believe that speculative fiction can help people imagine a brighter future, he said stories alone can’t save the world.

“I think they’re a necessary, if not sufficient, part of the process, [and] we need a huge tidal wave of mobilization that includes a huge amount of culture making. We’re going to need art. We’re going to need music. We’re going to need TV shows that do for solar panels what TV and movies did for cars back in the ’50s and ’60s, [making] car culture cool. We’re going to have to do that for these technologies of sustainability.”

But without massive organizing and political action, Hudson believes, “we could figure out how to communicate this to the public in a really effective way and still lose.”

Our Shared Storm touches on the conflicts that often arise when people and communities want to effect change—is it easier to accomplish goals through established political systems or through grassroots work that doesn’t rely upon state action?

Hudson has described solarpunk as a countercultural movement. “It should not be about the people in power,” he said recently. “It should be about the people who are not in power, who are sort of challenging those systems.” But after witnessing firsthand—and writing about—the geopolitical mechanisms that dominate spaces such as the annual COP meetings, he has come to appreciate the need to work within traditional political and diplomatic systems.

“I think learning how the institutions work—the national, local, and state governments that are trying to implement the treaties—and then kind of inserting yourself into those processes can be really powerful,” he said. “The stories are there to help people understand these dynamics and institutions, and help them get a little smarter about policy, get a little more strategic about where they put their efforts, [so they’re] not going to get taken for a ride.”

In Our Shared Storm’s most optimistic story, a strong labor movement is key to influencing government policy, and while he acknowledged that there is no one easy solution, Hudson believes that the working class uniting—and pushing for things like a Green New Deal through general strikes—has the potential to positively shape the path ahead.

So, with the scenarios laid out, and with some ideas about the actions necessary to avoid the worst-case ones, what kind of climate future does Hudson see us moving toward? That kind of prognosticating, he insisted, is not part of his project.

“What I was interested in was how we’re shaped by opportunities and material conditions,” Hudson said, harking back to his characters’ changing circumstances and swerving fates.

“All these things that I think end up shaping our lives—those were kind of the pivot points that I wanted [to show readers]. The point being that climate and the investments we make to deal with it are going to be a big factor in shaping those pivot points for billions of people.”

]]>“Professor Jeannine Hill Fletcher taught me that there are so many more dimensions to religion and theology than I originally thought, and that there is space for women in theology—an important message as a woman in theology myself,” she said.

She’s taken that lesson to heart: Ruiz, currently a student at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), hopes to one day work at a nongovernmental organization, or in government, focusing specifically on creating policies that improve the lives of women.

A native of San Francisco, Ruiz majored in theology religious studies at Fordham with a concentration in faith and culture and a minor in American studies. She also served as a member of United Student Government at Lincoln Center; wrote for The Observer; was a member of the Phi Beta Kappa, Alpha Sigma Nu, Theta Alpha Kappa, and Phi Kappa Phi honor societies; and even received the 2021 Undergraduate Student Award for Most Active in Promoting Diversity and Inclusion from the Office for Student Involvement. She also completed internships with the National Development Council—a nonprofit that works with both government and community organizations to support and preserve “homes, jobs, and community”—and with Zina Spezakis’ campaign for Congress.What do you think you got at Fordham that you couldn’t have gotten elsewhere?

Here’s a story that I like to tell: I arrived at Fordham a characteristically nervous freshman, daunted by a new city and the prospect of making social connections. On my way to audition for a club, I realized that I had no idea how to print the script I needed for my audition. Frantically, I approached an upperclassman to ask for help. Not only did he sit with me to figure out how to set up my printing account, he used his own credit to help me print my script. This unprecedented gesture exemplified the kindness and care that defines the Fordham community.

Academically, Fordham teaches its students to be deeply informed and concerned about injustices in the world, but also deeply moved to do something about them. Across disciplines, Fordham professors teach students not only about important issues in our communities but inspire their students to make a difference.

What Fordham course has had the greatest influence on you and your career path so far? How and why was it so influential?

Major Developments in American Culture, taught by Professor Diane Detournay. From academic discourse to everyday news, we often throw around terms like “systemic inequality,” “injustice,” and “oppression,” but we don’t spend enough time unpacking why these things happen or how they came to be in the first place.

Professor Detournay’s class allowed us to home in on the history of our country’s unfair systems and the ways in which they are perpetuated or upheld. Some topics we focused on were immigration, the prison-industrial complex, and the colonial history of Hawaii. I came away from her class with the confidence to articulate the history and mechanism of unjust systems, which was fundamental to my decision to study social policy for my master’s degree. I figured that the best way to combat systemic injustice is to change the systems that cause them in the first place.

Who is the Fordham professor or person you admire the most, and why?

This is a tough question because there are so many professors and people at Fordham I admire. If I had to choose, I admire Professor Jeannine Hill Fletcher. Among my non-religious peers, I’ve noticed that there is a general perception that religious people lack an awareness of societal discrimination. While it’s not her stated mission, I think Professor Hill Fletcher—who is Catholic—turns all of those stereotypes on their head. Not only is she a feminist theologian by training: she is very involved with advocacy work, as she is an prominent voice for faculty rights, and she is a dedicated ally to students of color and LGBTQ students. As someone who came to Fordham grappling with religion and trying to understand it better, it was really influential to meet Professor Hill Fletcher and see the kind of work she does.

Did you have any internships or any other experiences, such as clubs, that helped put you on your current path? What were they, and how did they prepare you for what you’re doing now?

I served on United Student Government (USG) for three years, culminating with a successful campaign for president. While USG is not an exact simulation of how state governments work, I felt that through my role, I was able to understand what it means to be a leader and how to deal with difficult issues because I entered my term right as COVID-19 hit and in the wake of the George Floyd protests. With the challenge of a pandemic and amid conversations about racial justice and everyday life, I found myself in a multitude of conversations about how to give students the best, safest, and most just experience possible.

During these conversations, I learned to play to the strengths of different personalities and work styles as I led the Senate and executive board, and I learned how to negotiate with high-level University administrators. I feel that the communication and leadership skills I gained through my role as president will be crucial to my future career in policy work, either as a government policy adviser or at an NGO.

Finally, as president, I accomplished several landmark projects that were the first of their kind at Fordham. They included Fordham’s first anti-discrimination policy for student organizations, Fordham’s first ceremony of recognition for first-generation students, and statements of support for Black, Burmese, and Asian American communities. While they were not policies in a public or social policy sense, these long-term projects trained me to see large plans come to fruition and to uplift a diversity of voices in respectful ways.

What are you doing now? Can you paint us a picture of your current responsibilities? What do you hope to accomplish, personally or professionally?

I am currently at the London School of Economics, pursuing my MSc in international social and public policy. I am continuing my passion for leadership by serving as a Student Academic Representative for my programme at LSE. After graduation, I plan to either pursue a Ph.D. or begin my career in public policy.

What are you optimistic about?

While I miss Fordham dearly, knowing that it is inspiring generation after generation of changemakers makes me optimistic.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Sierra McCleary-Harris.

]]>By the end of 2019, just as the virus was starting to make headlines across Asia, Devine and his frequent collaborator and producer, Chris Bracco, had begun to talk about turning those songs into an album. In early March 2020, Devine went to Bracco’s house in Connecticut, where they recorded some of album’s foundational sounds. He then planned to go through his usual quick cycle: finish recording in April, mix the album in May, master it in June, tour in the fall.

Instead, once the public health crisis made clear that traditional recording and touring would not be possible for the foreseeable future, Devine found himself with a luxury he hadn’t experienced much over his prolific career: extra time. The head of his record label, Triple Crown Records, assured him there was no rush to complete the album, which left Devine with plenty of room to experiment.

“I’m sure we would’ve made a compelling record [in 2020], but I can guarantee you, we would not have made the record we made,” Devine says. “It was nice to get some distance and perspective and come back to it with fresh ears. And I think that afforded us the opportunity to thoroughly explore every little weird thought and idea we had.”

Those weird thoughts and ideas culminated in an album that finds Devine exploring an expansive sonic landscape, with a more lush, psychedelic sound than anything he’s done on his nine previous solo records, or in his work prior to that in the band Miracle of 86. Among the reference points he cites for the album are the Beatles’ White Album, Wilco’s A Ghost is Born, and Elliott Smith’s From a Basement on the Hill—all works filled with experimental touches built atop foundations of more traditional rock and pop songwriting.

“We knew this was something we wanted to be a little bit more textured, layered, swirly, creepy,” Devine says.

A Music Career Shaped by Time at Fordham

Devine grew up in Brooklyn and Staten Island and started his first band, Delusion, as a teenager. That band would become Miracle of 86, which found some success in the punk and emo scene around the turn of the millennium, touring the U.S., Canada, and Europe, and releasing three full-length albums, the first of which—2000’s Miracle of 86 (Fade Away)—came out the November of Devine’s senior year at Fordham College at Lincoln Center.

Devine had enrolled at Fordham in 1998, where he double-majored in English and communication and media studies and lived in McMahon Hall for four years. He also wrote for and became features editor of The Observer, the student newspaper based at the Lincoln Center campus. While he took his studies seriously, Devine also used his time at Fordham to develop as a solo performer. He played shows around the city and on campus, and by the time he graduated in 2001, he had to decide whether to pursue a career in journalism or focus on his music.

In a 2012 profile of Devine in The Observer, Elizabeth Stone, Ph.D., the paper’s adviser during Devine’s time and still a friend of the musician’s today, recalled him telling her, “I have to give this music thing a shot. I’ll probably do something else in a year, but I’ve got to do this music thing. I’ll never forgive myself if I don’t.”

A year after graduating, Devine released his first solo album, Circle Gets the Square, on Immigrant Sun Records. The album was more personal and introspective than Devine’s work with Miracle of 86, and he continued to write and play solo shows while working day jobs. His next two albums, 2003’s Make the Clocks Move and 2005’s Split the Country, Split the Street, were both released on Triple Crown, and with them, Devine toured more extensively and grew his fan base by opening for acts like Brand New.

Since then, Devine has made a career as a prolific artist. In addition to his 10 LPs, he has released nearly a dozen EPs, several live albums, 12 split 7-inch records as part of his Devinyl Splits Series, and three albums as part of Bad Books, a project he started with Andy Hull of the band Manchester Orchestra. And over the years, along with numerous headlining tours, he has opened for artists like the Get Up Kids and Bright Eyes and played festivals like Coachella, Bonnaroo, and Lollapalooza.

While his path to music industry success differed from those of his peers who started touring widely as teenagers and forewent college, Devine says that his time at Fordham was an important part of his development not only as a person but as a songwriter.

“I feel like it was an immersive environment through which to learn ways to interpret and interpolate the world,” he says of his college experience, recalling a piece of journalism advice he got in a class with Professor Joseph Dembo: “Specificity breeds believability.”

“That’s something that is a big part of how I see the world and how I try to write,” Devine says. “To interrogate, to ask questions—I feel like that part of journalism continues to be a central aspect of what I do as a songwriter. If I had started [touring full-time] three years earlier, I would’ve missed what I got to do [at Fordham], and I actually think it would’ve had a detrimental impact on what I’ve done as a musician.”

Beyond academics and critical thinking, Devine says that he met many of his closest friends at Fordham, and he tries to visit the Lincoln Center campus at least once a year just to walk around or catch up with Stone over a cup of coffee.

“My experience at Fordham was formative and foundational in the sense that I feel like it furthered the project, in a very meaningful way, of exploring an idea of who [I am],” he says.

‘Navigating the Complexities of Personhood’

That exploration of the self is a central theme of Nothing’s Real, So Nothing’s Wrong.

“What I think I’ve always tried to do,” Devine says, “is to try to capture what it was like for this person to be navigating the complexities of personhood at this given moment. That tends to be the project for me. Which is a fertile project, because I think being a person’s pretty complex.

“This record, I would say, is a lot of liminal subconscious examinations of pivot points in life, places where you are examining where certain defenses or survival traits may no longer serve you. The ways in which we could be trying to protect ourselves, but really [are] pushing people away. That weird dance on the head of a pin between, ‘What is a boundary that is healthy and what is me removing myself from things that are actually good for me?’”

And while none of the songs are overtly about politics or the pandemic, the album also grapples with how to make peace with oneself in a world of pain and suffering. When the album’s first single, “Albatross,” was released in January, Devine described it as “a hard reboot, a fragmented emptying-out for us strugglers whose life experience invalidates cookie-cutter solutions or miracle cures or 21st-century coping mechanisms.”

He is quick to point out that that “emptying-out” does not mean ignoring the suffering of others or forgoing responsibility for one’s actions.

“It’s not about an abdication,” he says. “Therapists talk about how guilt and shame are useless; wise remorse is actually a more fruitful way to move around in that which we have done, because it indicates a willingness to learn something and a way to detach from being completely self-lacerative. … What’s the most actionable philosophy to get through the day?”

Or, as he says about the meaning behind another album highlight, “Override”: “How do I get rooted while the Earth moves all around me?”

Staying Grounded and Returning to the Road

For Devine, staying rooted includes finding time to meditate and practice gratitude. He was raised Irish Catholic, and while he no longer considers himself to be a Christian, he says that his religious upbringing is “deeply embedded” within him and he still finds value in praying.

“Stopping in any given point in a day to say a few things for which you’re thankful and say a few things with which you’d like some help—that’s the guts of it,” he says of his prayer routine, adding that meditation gives him “five to 10 minutes a day where I’m separated from the noise of existence for that time.”

Another thing that grounds Devine—and that served as a point of reflection while writing the songs on Nothing’s Real—is being the father to a 6-year-old daughter, which he says is his “most important job.” When he begins a six-week U.S. tour in early April, it will be the longest he’s been away from home since his daughter was born, which he says has caused him some ambivalence, despite being excited to perform the new album’s songs in front of fans.

For many musicians, a return to touring after COVID-related cancellations will also mean a return to earning a living—something that has been difficult for artists who rely on playing shows to bring in income. Devine says that he has been fortunate not to face as much economic devastation as many of his peers, though, which has largely been the result of the Patreon subscription service he launched at the beginning of the pandemic.

“We’ve had such a miraculous success story with the Patreon,” Devine says of the service, which allows fans to pay a monthly membership fee in order to gain access to exclusive songs (both originals and covers), livestreams, discounts on merch, and more. “I have been really fortunate not to be financially ravaged by this, and it’s been almost [entirely] because of the Patreon.”

In monthly videos in which Devine answers submitted questions, it’s clear that he has a special relationship with his fans, who ask him everything from what inspired certain songs to what his favorite vegan meals to cook are. That loyal following is further shown by at least two people getting tattoos inspired by the new album.

Regardless of whether he continues to embark on tours as big as the upcoming one (“Maybe I’ll do it until I physically can’t. Maybe in five years, I’ll be like, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore,’” he says), Nothing’s Real, So Nothing’s Wrong proves that he has plenty of room to grow what has already been a long, successful career—one that has offered both him and his fans a chance to find communion in music during difficult times, something alluded to in a lyric from “Albatross”:

“If you’re sinking, sing along.”

Nothing’s Real, So Nothing’s Wrong was released via Triple Crown Records on March 25. Visit Devine’s website for tour dates and more information.

]]>“The Observer has played a tremendously important role throughout the pandemic by keeping all of our students connected to campus, no matter where they’ve been living,” said Laura Auricchio, Ph.D., dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center. “I’m hugely grateful for their commitment and proud of the character they have demonstrated at every turn.”

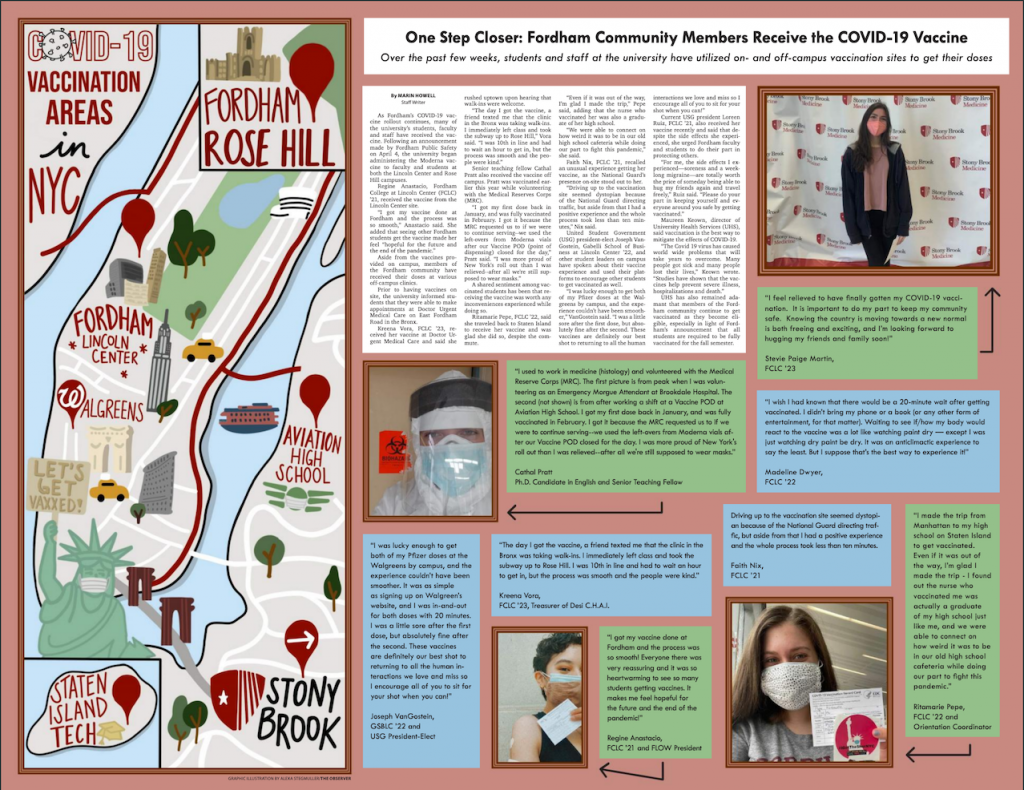

This year marked a historical milestone for The Observer, which celebrated its 40th anniversary by creating a special online edition about its history, current members, and alumni who are now working as full-time journalists across the country. But much of the focus of their news coverage from this past year was on the pandemic, said newspaper staff adviser Anthony Hazell.

“There were so many different angles to cover: how students in different time zones were attending remote classes, how hybrid learning was going, how student clubs tried to maintain student life on campus, how health precautions and protocols affected the mental health of students and their families,” said Hazell, a full-time director of communications at Bay Ridge Prep who advises Fordham students with Molly Bedford, a design editor at The New York Times. “They were very personal stories to both the people being interviewed and the students themselves.”

The student news team was “thrown off the digital cliff” during the pandemic, said Grace Getman, FCLC ’22, The Observer’s managing editor. They were forced to adjust to new working conditions and time zones, from Oregon to Louisiana to Russia. But this year was also a period of opportunity, she said.

“It gave us a real chance to examine why we have the rules that we do and why we do the things the way that we do them,” said Getman, who highlighted her team’s reporting on how the Fordham community was impacted by COVID-19 vaccines. “It broke the chain on a lot of things and gave us a huge opportunity to connect and collaborate in ways that we never even thought of before.”

In addition to the American Scholastic Press Association award, two members of The Observer—Arts and Culture Editor Madeline Katz and Assistant Features Editor Aidan Lane—were recognized by School Newspapers Online (SNO), a website platform that collaborates with collegiate news publications across the country, for their stories “Hell’s Kitchen Free Store is Priceless” and “Labor Organizers Shine During May Day Protests.” Their stories were featured in the online Best of SNO showcase that highlights top student work.

“It’s intimidating, but inspiring to know that people are going to be reading what we did, what we said, and what we recorded,” Getman said. “It sounds a bit cheesy, but history has its eyes on us. This time, this moment, is one that people are going to want to know about. Not only do we have an obligation to our readers right now, but we also have an obligation to the future.”

The May 21 event, hosted by the Fordham University Alumni Association (FUAA), recognized alumni with a graduating senior in the Class of 2021, along with members of the Parents’ Leadership Council (PLC) and their graduating students.

Matthew Burns, associate director for young alumni and student engagement, and Kathryn Mandalakis, assistant director of the Fordham Fund, kicked off the virtual event. Mandalakis thanked the council members for making Fordham “a real family affair,” and fondly remembered her own graduation in 2019.

“It has been two years, almost to the day, since I was attending my own PLC and legacy family reception, as my dad is an alumnus himself,” she said. “It feels really special to be here with you all and celebrate your graduates and celebrate the long maroon line with your legacy.”

During the event, two families reflected on their time at the University and on what it means to share an alma mater, with the graduates interviewing their parents.

Anthony Quartell, FCRH ’64, whose daughter Olivia Quartell, FCRH ’21, served as president of United Student Government and a mentee in the Fordham Mentoring Program, said that after his family moved near the Bronx campus, his father suggested he enroll at Fordham to learn about religion.

“I had no idea who Ignatius Loyola was,” he said, noting that he had attended public schools, including Bronx High School of Science, but the Jesuits at Fordham taught him “a whole lot more [than religion]. They taught me how to think.”

Olivia said Fordham wasn’t initially one of her more “obvious” picks, but her experiences at the University were nothing short of a gift.

“I think it’s funny that a lot of people who found such a home here didn’t necessarily seek it, [but]it was definitely something that Fordham gave to them. … It just naturally kind of comes from being in this place.”

Katherine Beshar, FCLC ’21, who writes for The Observer, the student newspaper based on the University’s Lincoln Center campus, transferred to Fordham during her junior year due to a sports injury, but she echoed Olivia Quartell’s sentiment. She said “home” is a fitting word for what the University has given her.

She asked her mother, Maureen Beshar, FCLC ’86, about her own undergraduate experience. Like her mother, Katherine was a commuter student. Maureen commuted from Brooklyn and initially worked two part-time jobs before pivoting to night school so that she could work full time.

Maureen, who is now a member of the Fordham President’s Council, said she continued to experience Fordham’s sense of community, maybe even more so, after graduating. “The Fordham experience [is]really now just beginning,” she said. “There’s so many different ways you can stay involved as your life changes and … as you go forward in life. You can go back home [to Fordham], because I think you’ll always find some way to be involved.”

John Pettenati, FCRH ’81, chair of the FUAA, formally welcomed graduates into the alumni community and urged them to stay involved, to “give your time, your treasure, and your talent back to the school. It is so important for [others to be]inspired by all of you.”

A recorded toast from Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, brought the event home.

“My dear friends, we gather to toast you on your impending graduation that has special meaning for you and for your parents because by graduating you have not only followed in their footsteps, you have become men and women whose lives have a shared experience—an experience that makes you even closer than you were before,” he said. “You and your parents are both Rams.”

]]>Partridge-Hicks, a junior at Fordham College Lincoln Center who was then the news editor of The Observer, raced down to the office to write the story. When she got there, the first thing on her computer screen was a video she had worked on earlier in the week featuring students’ reactions to COVID-19.

“[There] was that video of students saying, ‘it’s not that big of a deal,’ and there I was writing that they canceled [on-campus] school,” she said.

“It was just so surreal,” added Partridge-Hicks.

Expanding Coverage

While the COVID-19 pandemic has forced Fordham student journalists to move their operations entirely online and remotely cover the news that’s impacting their community, it’s also given them an opportunity to expand their coverage and try new things.

“What it has done is make us get a little more creative in how we’re seeking out stories,” Owen Roche, outgoing editor-in-chief of The Observer and Fordham College at Lincoln Center junior, studying English and new media and digital design, said. “For example, our arts and culture team is covering a group of Fordham kids who have made a Minecraft server, where they’ve recreated the Rose Hill campus. These sort of things may have flown under our radar or have maybe gotten buried…so this situation is sort of giving us new ways to report…and new things to report on.”

The publication has also been working on “news you can use” stories, such as one on ways to maintain a healthy immune system.

The pandemic has allowed The Observer to fully move from a biweekly to a weekly production schedule. The staff had begun the transition last semester, publishing a print issue biweekly, and articles online in the “in between weeks.”

“The only silver lining I can really identify from this is … we’re producing a full issue every single week now, which we’ve never been able to do,” said Partridge-Hicks, who has since been elected editor-in-chief of The Observer. “It was a goal that we felt maybe was a year off or six months away and we just were able to respond to the situation. I think this has also shown us how much we can achieve digitally.”

For the editors at The Fordham Ram, Rose Hill’s student newspaper, the pandemic shifted their coverage to trying to keep the community informed and provide some sense of normalcy.

“We’ve been trying to highlight student groups and clubs that have been active on social media and online events that they’re putting on,” said Sarah Huffman, a Rose Hill junior and news editor. “We’ve also been doing a lot of coverage of budgets and what is happening with the reimbursements and seniors and commencement. A lot of people have questions right now so we’re just trying to figure out what people care about the most and trying to get answers.”

What’s most important during this time, according to Helen Stevenson, editor-in-chief of The Fordham Ram, is still capturing the student experience. That includes reaching out to student groups, faculty, and staff to see how the pandemic is affecting them.

They’ve also tried to utilize their culture section to include playlists from editors and a “quarantine diary series”—personal features that can help readers stay connected to the Fordham community remotely.

In one recent diary column, Erica Scalise, projects editor emerita for The Fordham Ram, wrote about how she’s struggling to find joy during this time.

“I keep feeling invaded by those classist social media posts about the people who stayed home and read books and cooked meals, about how joy isn’t canceled and laughter isn’t canceled and how I’m somehow supposed to feel compelled to start baking bread because of this,” she wrote. “Yes, I could bake bread while cogitating on all of the ways I could possibly write about New York. I could remain painstakingly hopeful or possibly even amass enough sentimentality to absolve this state of listlessness that lives with me most, if not all, of the time. But I don’t want to make a sourdough starter. I don’t want to take up running or even pretend to like it at all and I’m tired of peeling back layers of myself that were formed in a city where I’m suddenly not.”

Telling COVID-19 Stories

One of the biggest challenges the student journalists have faced is trying to tell COVID-19-related stories in a different way, a problem that many media companies in general are facing, according to Molly Bedford, a design editor at The New York Times who also serves as a visual adviser to The Observer, and an adjunct instructor at Fordham.

“It’s also a time where you need to reinvent your coverage a little bit—it’s a story that needs a new angle, they’re really trying to reinvent new ways to tell similar stories and that’s a challenge across newsrooms everywhere right now,” Bedford said.

Partridge-Hicks said they’ve been trying to cover stories that are unique to their audience.

“We can’t really compete with CNN and The New York Times, but what is beneficial to being college reporters? What’s the information, what’s the data that we can get that makes us stand apart?” she said.

One of the stories that stood out examined the impact on study abroad programs.

“I spoke to nine or 10 students with really different experiences,” she said. “One girl was studying abroad in London, but her parents lived in Tokyo, but they wanted to send her back to the [United] States, and at the time they thought that McMahon and campus housing would be open.”

At The Ram, Huffman said that a piece they published shortly after news broke that campus would be closing for the semester really left an impact.

“[We] wrote a feature about how campus changed as soon as people left and how it was affecting business owners in the community—all the different ramifications of this virus and of the campus shutting down,” Huffman said. “That was emotional to read and work on because everything was changing and we didn’t really know what was going to happen.”

Bedford said she was impressed with the variety of coverage the students were able to tackle.

“They’re able to take this global story and make it relevant to our community,” she said. “Many years from now…students will look back at the time and look to The Observer’s coverage and know what it was like to be a student in 2020.”

A Great Balancing Act

Another challenge for the staff members is the reality of being a student journalist in 2020—having to cover what’s happening and deal with the fact that it’s also happening to them.

“The one thing I learned from the first day on the job is being a student journalist is one giant conflict of interest,” Roche said.

While the staff members have tried to mitigate some of that, by having commuter students report on residential life activities or having students report on programs they aren’t enrolled in, sometimes the emotions are unavoidable.

“When we first got the news that we wouldn’t be returning to campus for the remainder of the semester, it really broke my heart because I’m a current senior,” said Courtney Brogle, outgoing managing editor of The Observer. “They announced that graduation was postponed and that also was so heartbreaking to hear—obviously it was the only option that we had, but it’s still so heartbreaking because you work so hard and build such community and we don’t know when we’re going to see each other again.”

Stevenson said that she usually goes into a “robotic mode,” when breaking news happens, so when she heard that campus was closing for the semester, her adrenaline kicked in.

“I remember receiving the emails that we would not be going back to [campus]and again my fight or flight kicks in—I typed out an article real quick, and then it went out, and not to get too personal but I was bawling,” she said. “It really just hit me that the world would be changing.”

Passion and Commitment

While adjusting to their “new normal” was a challenge, many said they’re grateful to have their fellow newsroom colleagues for support during this time.

“Having production every week and still being able to write and still being able to cover Fordham events and ideas and stories—it’s kind of helping [us]keep sane through all of this, myself included,” Stevenson said.”I know I really do well with the routine and The Ram is such a big part of my life and everybody else’s life when they are on campus.”

Roche said that he was expecting a “downturn in production” with everyone moving to remote reporting, but that never happened.

“We were expecting a dip in productivity and we saw the opposite, which was surprising, and a testament to this staff and all they’re capable of and just the ambitions they have,” he said. “I think this new situation has shown the power of not being afraid to try new things and ask and take risks.”

Bedford and fellow adviser Anthony Hazell, FCLC ’07, said that they were proud of the dedication the students have shown.

“I think most people that age would give up on other things like a student club that they are part of, but I would say that the students on The Observer pulled together in a way that is the strongest that I’ve seen,” said Hazell, who works as the communications director at Bay Ridge Prep, a private school in Brooklyn. “It’s just really impressive the content is stronger than it usually is, it’s strong to begin with, but it’s certainly stronger than it usually is.”

Partridge-Hicks said her goal is to continue to build on that content, using what she’s learned during this time period, when things “go back to normal.”

“That means extensive social media, podcasts, multimedia videos… I think we’re all very proud of what The Observer is producing but we just want to make it more dynamic and more accessible for our readers.”

]]>She took an unconventional approach to her admission essay—she wrote a fictional story about how Dionne Warwick and the Psychic Friends Network predicted she would go to a school that bears her last name. “This was a time when that show was big, and when there really wasn’t a Fordham presence in California,” the San Francisco-area native explains.

Her risk paid off, and she continued to hone her writing as a communications major at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, where she wrote for The Observer. She graduated in 2001.

“At Fordham I learned to tell really good stories,” she says, “about all sorts of topics, including things out of my comfort zone.” And though she didn’t end up pursuing a journalism career, her undergraduate experience helped get her a role as a grant writer for The Salvation Army in San Francisco. “I found a career I didn’t know existed, where I am able to help nonprofits and my community,” she says. “And that’s all from a journalism standpoint, which I owe to Fordham.”

It was also at the Salvation Army that Eva first thought about getting involved with a local Fordham alumni chapter. “My boss was very involved in his college’s alumni association, and it had just never occurred to me,” she says. So she contacted the head for the Fordham Alumni Chapter of Northern California, Mark Di Giorgio, and asked how she could help.

“Mark was a tremendous mentor who really kept Fordham grads in the area connected,” she says. When a job opportunity arose in Los Angeles, she promised she would get involved with the chapter in her new hometown.

Since her arrival in the city three years ago, she has done much more than that. With the help of a few fellow Fordham grads, she has revitalized the chapter, introducing two signature events.

She first connected with Caroline Valvardi, FCRH ’10, a “powerhouse behind group,” she says, who has since moved to Washington, D.C. Together, they brought on David Martel, FCLC ’00, and Kevin Carter, FCRH ’12. More recently, Lori Schaffhauser, LAW ’00, joined them. “It’s one of the most well-rounded teams I’ve ever worked with,” Eva says of her fellow Fordham Alumni Chapter of Los Angeles leaders. “It’s all ages, all different industries, all different types of talent. … It’s a great crowd, and they’re just happy to help. If this were corporate America, I would be really excited. And, of course, we’d love to have more.”

The group also reflects the diversity of the local Fordham audience. “LA is so vast; it’s just a different market,” she says. “But being here, we also have unique opportunities to leverage alumni in fields like entertainment. This is the entertainment town, and you don’t quite realize how many different aspects there are within that until you’re here.”

That’s why one of the chapter’s new signature events is a summer Entertainment Panel featuring Fordham grads who range from TV actors to Marvel writers. “It’s sold out both times we’ve held it,” Eva says, as has the new Malibu Wine Hike in the spring. Along with the annual LA Presidential Reception in January, these events have come to form the core of the chapter’s offerings for alumni.

“We’ve also tried baseball games, basketball games, holiday happy hours, all of that. We’re trying different locations and frequencies. It’s all trial and error to see what people here want,” Eva explains.

“This city is a bit fragmented, so I just look forward to linking this community together a bit more, to bringing more Fordham people together.”

Fordham Five

What are you most passionate about?

I’m passionate about connecting people with organizations or communities or causes they care about that provide wellness for others, and about giving everyone access to opportunities they might not normally get. In my work, a lot of times that’s through philanthropy, like raising funds for after-school programs for children from low-income backgrounds. They provide more than education—they also provide health and wellness support. Nobody operates at their full capacity without having access to basic needs like nutrition, education, and mental health. So I’m passionate about providing access to that, but I’m also passionate about giving donors an opportunity to see how their contributions really make a difference by hosting community events.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

A former CEO I worked with, who was such an inspirational man, once shared a definition of disillusionment that has stuck with me. He said that disillusionment is what happens when you walk into a situation with an illusion of how it should be. Since then, I have made an effort to address most things in life with an open mind and not with preconceived notions that can lead to disappointment. It’s hard, but it works.

What’s your favorite place in New York City? In the world?

My favorite places in New York City are the Lower East Side, West Village, or anywhere south of 14th Street, places like the original Five Points neighborhood, where real old New York is and where New York came into being. When I lived in New York right after college, I had a book that listed all these historic spots. And I would take the train with this book and wander around and just start marking off places. Lower Manhattan is just rich with history.

In the world, I would say Paris. I just went for my birthday earlier this year, and I hadn’t been since I was 11 or 12. There’s a ton of history there too, of course, which is perfect for me. Renoir is my favorite artist, and his studio there is now a museum, which I got to see on this last trip. I just loved tripping around the cobblestone streets and the old shops in that hilly area near the basilica, finding the oldest restaurant and the oldest bar and the oldest of everything.

Name a book that has had a lasting influence on you.

There’s a book I read a few months ago that I think will stay with me for a long time. It’s called The Great Work of Your Life: A Guide for the Journey to Your True Calling, and it’s by Stephen Cope. It’s a little self-help, in a way, but what I really enjoyed is how he tells a lot of tremendous stories about people who really followed their passion. I especially loved the stories about Jane Goodall and Gandhi, those two stuck out to me. There was so much I didn’t know about their lives or why they chose to do what they did. Understanding why they made these conscious decisions was inspiring.

Who is the Fordham grad or professor you admire most?

I would say Elizabeth Stone, who founded and ran The Observer at Lincoln Center for a long time. She was a big supporter. She encouraged me to push the envelope a few times, to take difficult articles even if they might not get published, and even though it sometimes frustrated me at the time, I am so grateful for that opportunity that helped me learn so much. I took writing classes with her too, but it’s one thing when you’re in a class and you’re writing papers—working on a newspaper is a totally different thing. You’re on a team with everybody. You’ve got co-writers, you have an editor … it’s real life. And that was an opportunity that I wouldn’t have taken advantage of if she hadn’t pushed me in that direction.