Unlike other rich countries, the United States has few universal federal family policies, like paid leave or child care subsidies. During the women’s movement of the 1970s, the country considered the idea that government and employer policies could help parents work and care for their families, as Kirsten Swinth, a history professor at Fordham, has written. But the Reagan era ushered in a different idea — that the government should not interfere in family life.

“This was very compelling — ‘I want control over how I raise my kids,’” said Professor Swinth, who studies women’s and economic history. “But practically, it meant that the systems that would aid parents, especially as women went into the workplace, like after-school and summer care, didn’t get funded.”

]]>“We’re crushing parents under an enormous burden, for the benefit of society, and we’re sort of free-riding” on them, Professor Swinth said.

]]>“You have an obligation to behave in the interest of that organization,” said Linda Sugin, a professor of nonprofit law at Fordham University. “The problem is, when you’re on both sides of the transaction, then we’re skeptical that you’re going to put the organization’s interests before your own.”

Ms. Sugin said the institute could have reduced its risk by soliciting bids from competing firms to gauge whether the insiders were charging market rates. The institute could have asked its leaders to recuse themselves from the decision to hire their own companies, she said.

The Many Voices Prize was established in June by Elizabeth Stone, Ph.D., the Fordham English professor who also helped establish The Observer itself in 1981 and served as its adviser for 35 years. Carrying a cash award of $1,500, the prize will be awarded with a preference for Observer staffers who are first in their families to attend college or who come from other underrepresented groups.

Stone, a first-generation college graduate herself, believes that journalism has “a kind of moral obligation to be a big table at which everybody could sit.”

The prize is “a way to invite people to the journalistic table,” she said. “The hope is that once they join, they will feel invited, and they will speak what’s on their mind, they will do stories that are on their mind.”

Stone’s gift advances a key priority of Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, the University’s $350 million fundraising campaign, which seeks to reinvest in the entire student experience and foster a more diverse and inclusive Fordham community.

Stone’s gift will fund one Many Voices prize in the coming academic year and eventually three per year. The prize will be awarded for three nonfiction articles or their equivalent published in The Observer, either in print or online, by a staff member. In addition to writing, these works could include video, podcasts, photography, graphic design, graphic texts, cartoons, or other formats that emerge from the evolving media landscape, Stone said.

Alumni Involvement

The prize is coupled with a new effort to advance the career development of Observer staff members by harnessing the connections and expertise of Observer alumni, many of whom got their professional start on the award-winning publication and stay in touch with each other.

An alumni advisory board, formed from the Observer Alumni Affinity Chapter, is being created to advise Student Affairs in awarding the prize and to help connect the paper’s staff members with mentoring, networking, internship, and job opportunities. The board will also help with fundraising to augment the prize, said Anthony Hazell, FCLC ’07, communications director for a K-12 private school and The Observer’s editorial adviser since 2016.

Students for whom the award is meant are often working to meet their college expenses, “so hopefully offering a financial award to make up for the time that they spend on The Observer can help get their voices heard,” said Hazell, who served as the paper’s editor in chief as an undergraduate.

Stone announced the prize June 9 at the annual Block Party celebration at the Lincoln Center campus, saying that a robust diversity of journalistic voices is needed for the survival of our democracy.

The award also reflects her own experiences, she said in an interview. She challenged stereotypes in one of her earliest pieces of journalism, “It’s Still Hard to Grow Up Italian”—published in The New York Times in 1978, it incorporated narratives by several Italian Americans, and much of her early writing was about being the granddaughter of Italian immigrants at a time when, in popular culture, Italians were routinely associated with the mafia.

She hopes the prize will inspire people from underrepresented or misrepresented groups to speak out as well. “What I really hope is that they will speak to who they are, in terms of the subjects that interest them, the politics that interest them, the personal essays that interest them, in the same way that I did.”

Striving for Diversity

Allie Stofer, Observer editor in chief and an incoming senior at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, said she was excited to learn about the award because its cash prize could help students of diverse backgrounds make the time commitment required of Observer staffers. Maddie Sandholm, the managing editor and also an incoming senior at the college, noted that the Observer will also award a new $1,200 scholarship to one of its staff members in the coming year for similar purposes.

She said the paper has been making other diversity-related efforts in recent years, such as relaxing its meeting attendance requirement—to accommodate potential staffers who have conflicts—and hosting workshops on things like keeping biases out of headlines and page layouts.

“The chance to uplift new and underrepresented voices is something that has always and will always be invaluable to The Observer, and so we are honored that Elizabeth Stone … [has established] this prize to support and embody that mission,” Sandholm said.

Working with The Observer was the most engaging part of her job at Fordham to date, Stone said. She fondly recalled the daylong barbecues she hosted for the staff as a sort of retreat, as well as tricky editorial questions that fostered “teachable moments,” she said, “where there was a really vital conversation, and where I was delighted not to be the one who knew everything.”

She is proud to have helped develop and strengthen the paper over the years and hopes the prize will help The Observer stay in step with the anti-racism and multicultural perspectives that are being amplified in the Fordham curriculum.

“I really do believe in a kind of multiculturalism, but to believe in it, you have to see it all around you,” she said. The prize, she said, is “a way of helping to realize that vision.”

To inquire about supporting the Many Voices Prize or another area of the University, please contact Michael Boyd, senior associate vice president for development and university relations, at 212-636-6525 or [email protected]. Learn more about Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, a campaign to reinvest in every aspect of the Fordham student experience.

]]>Keyes and his mentee, Elizabeth Hawes, were recognized for showcasing “the best of what it means to treat those on the inside as equally human, equally meaningful, equally as capable of stirring our imaginations through the written word,” according to PEN America. Each of the eight winners received $250 and a set of books chosen by their respective mentor/mentee.

A ‘Golden Partnership’

Hawes, who has been incarcerated since October 2008, contacted PEN America in hopes of getting feedback on her play Supernova, a series of monologues and scenes about women’s experiences in prison. She asked to be paired with a playwright who has experience staging a play. “Was what I had written clear? Was putting a Busby Berkley-style ballet in the middle madness or fantastic? Did the play as a whole come across as too heavy or too sad?” she wrote in an essay on PEN America’s website.

In Keyes, she found not just a source of feedback and support but a fellow writer with whom she could collaborate. “Regardless of where my play lands, I know that it is good,” she wrote. “It is moving and interesting and relevant to the conversation of mass incarceration. I present it with confidence. Jeffrey gave me confidence.”

Initially “blown away” by Hawes’ writing, Keyes said it was clear that he would be working with her not as an educator but as a colleague, an approach that can be rare for someone who is incarcerated. And he got a lot out of the relationship, too, “really [embarking]on a journey together,” he said, and receiving encouragement from Hawes when he needed it in return.

Keyes said his Fordham education made him truly appreciate the value of a strong mentor-mentee relationship, and understand “what it means to be a mentee and also to have extraordinary mentors.” For him, serving as a mentor for PEN’s program is about more than paying it forward—it’s about providing access, too, since receiving quality feedback from other writers is essential. “I think that it’s affirming for writers who have limited resources … to be able to share their work. I’m lucky that I have friends and colleagues that I can share material with and get high-quality feedback—not everybody has that access.”

The PEN America Prison Writing program had been on Keyes’ radar for some time, but he wanted a stronger sense of success and validation “besides just degrees” before he felt qualified to mentor. “Which is ridiculous,” said Keyes, whose plays have been developed or featured at such theaters as SoHo Playhouse, 59E59, and the Old Vic. It “doesn’t necessarily make you any better … or make you more qualified to be a mentor or to share insight on the world. I think that anybody can.”

Writing His Own Path

Keyes, who hails from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, said he has always been a writer, but when he moved to New York to attend Fordham College at Lincoln Center, it was to study theater. “I think theater is an amazing foundation for all different types of literature,” he said, adding that the Jesuit education he received at Fordham allowed him to explore a wide range of subjects.

And explore he did. After Fordham, he enrolled in Columbia University’s MFA program in playwriting and graduated in 2010. Since then, he’s continued to show versatility as a writer. He co-authored a New York Times best-selling novel, Killer Chef (BookShots, 2016), with James Patterson, and he contributes travel and lifestyle features to such publications as Metrosource Magazine and Passport Magazine, among others.

The Next Act

Currently, Keyes is working with a fellow writer from Milwaukee on a script for a new TV show pitch about the city in the 1980s, which he said is already garnering interest, as well as a solo book project.

Another one of his more recent projects, Digital Arrest, took the top prize in the Creative Technology category at the NYC Media Lab 2019 Demo Expo. A collaboration with Columbia’s SAFE Lab, Digital Arrest offers people released from prison “opportunities to gain relevant tech skills and earn a living utilizing their expertise to infuse the tech industry with nuanced cultural perspectives and deeper context regarding social media use, privacy, and ‘freedom of speech.’” Keyes said the project is based on the story of Jarrell Daniels, whose Facebook and Instagram accounts were used as evidence to help convict and sentence him to six years in prison when he was 17 years old.

“There’s a lot of nuance in social media,” Keyes said, adding that he hopes the project can help people coming out of prison to “gain a deeper sense of right and wrong social media practices,” and be mindful of how what they post can be misinterpreted.

“I think that social justice is personal,” he said. “I think there’s a lot of change that can happen and I think that we’re at a place where we can really start making that change.”

]]>The fundraiser? An online auction, the third such event hosted by the Fordham College Alumni Association (FCAA), with a novel twist this year: celebrity alumni. Several offered virtual face time to the highest bidder, helping to propel the event far beyond its usual total.

The auction “gets bigger and better every year,” with all proceeds going toward scholarships and grants for students, said Debra Caruso Marrone, FCRH ’81, the association’s president.

It’s one of several events sponsored by the FCAA each year, complementing the broader efforts of the Fordham University Alumni Association, the Office of Alumni Relations, and other groups that serve students and the alumni community.

Founded in 1905, the FCAA is the University’s oldest alumni organization, and primarily serves Fordham College at Rose Hill students and alumni.

Contacting Celebrity Alumni

The idea of featuring celebrity alumni in December’s auction was driven in part by the pandemic, which put the kibosh on, say, auctioning off event tickets. “We really had to pivot,” said Christa Treitmeier-Meditz, FCRH ’85, who spearheaded the effort to reach out to various prominent alumni.

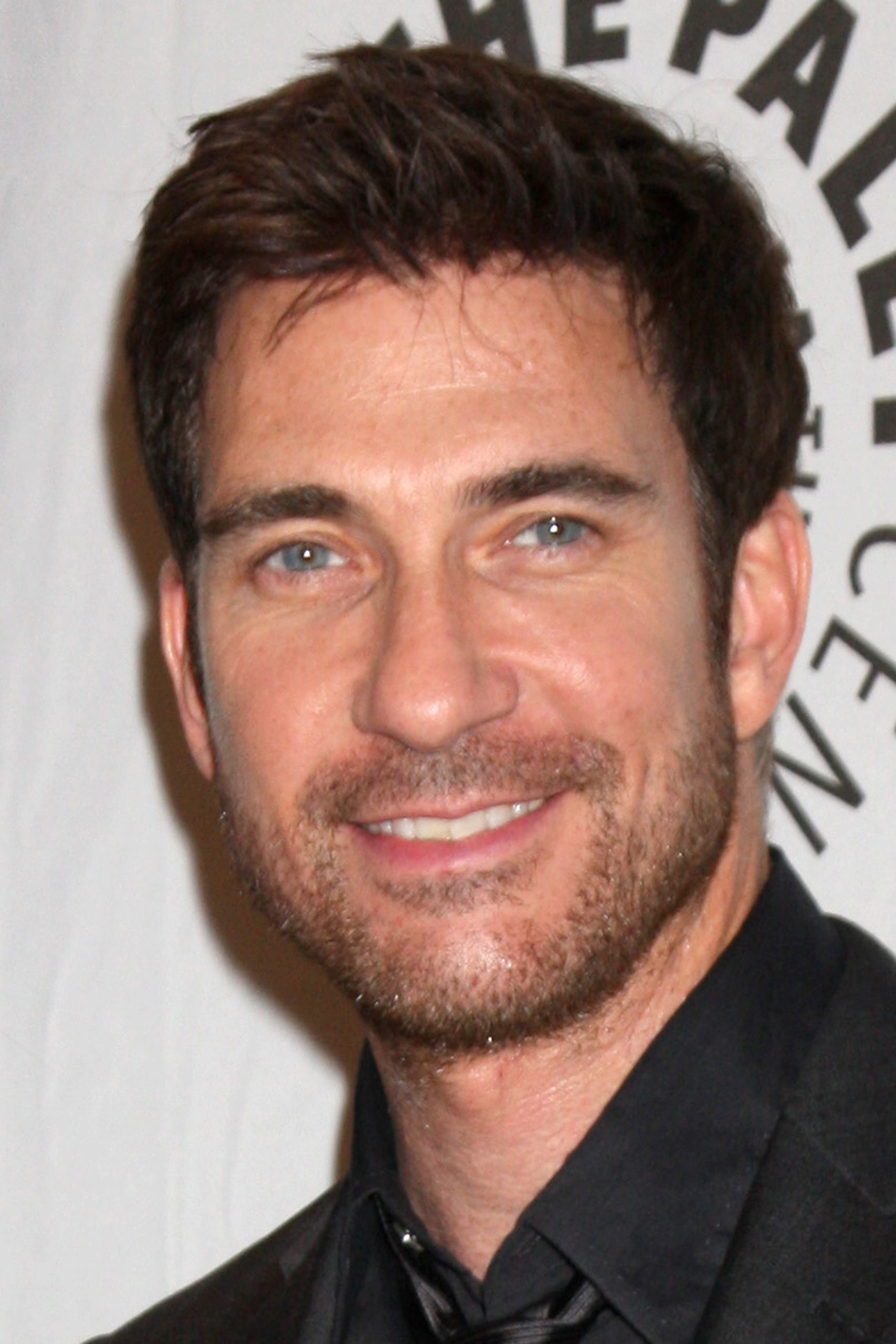

In the end, they were able to auction off a virtual comedy writing lesson with Saturday Night Live writer Streeter Seidell, FCRH ’05 (someone bought that for his wife, an aspiring comedy writer, Treitmeier-Meditz said). They also got help from some prominent alumni thespians: Golden Globe winner Dylan McDermott, FCLC ’83, contributed a virtual meet, and Golden Globe winner and former Oscar nominee Patricia Clarkson, FCLC ’82, contributed a virtual master class and a post-pandemic in-person engagement—dinner out and tickets to the next Broadway show she appears in.

People also contributed various items, memorabilia, or experiences, such as a master cooking class or a trip around Manhattan by yacht. “It’s everything and anything,” Treitmeier-Meditz said. “The Fordham alumni community is very generous.”

Other planned events were canceled due to the pandemic lockdown last year: a sit-down for a dozen alumni with John Brennan, FCRH ’77, former CIA director and counterterrorism adviser to President Barack Obama, and an event with sportscasters Michael Kay, FCRH ’82, and Mike Breen, FCRH ’83.

Through such events, the association has raised money for various funds, including a summer internship fund for journalism majors, recently renamed for Jim Dwyer, FCRH ’79, the New York Times columnist and Pulitzer Prize winner who died in 2020. A new scholarship fund named for Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, is for students who reach new heights of academic achievement after arriving at the University.

The association provides other important support such as funding for undergraduate research and for student travel, noted Maura Mast, Ph.D., dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill. “I’m so pleased to see how that support has grown over the past several years,” she said. “I am grateful for their commitment to the college, to our alumni, and to the larger Fordham family.”

The association’s Giving Day gift—a matching gift—was split between two scholarship funds: the FCAA Endowed Legacy Scholarship, a need-based scholarship for legacy students, and the Rev. George J. McMahon, S.J., Endowed Scholarship, awarded to students at Fordham College at Rose Hill and the Gabelli School of Business.

Serving on the board is a labor of love, Caruso Marrone said. “We’re doing something good: we’re raising funds, we’re helping students go through school,” in addition to bringing alumni together at events, she said. “The members of our board [are] of various age groups, various backgrounds, various careers, [and] we all come together and do this work and enjoy it immensely. We have just a great group of people who are dedicated to Fordham.”

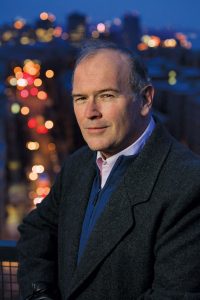

]]>“The angels have a bard. Fordham, and New York City, mourn the death of Jim Dwyer, who was truly the voice of average New Yorkers,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “One could write a book of several volumes extolling Jim’s virtues and his contributions to the city he loved and chronicled. He was a true son of Fordham, and of New York. Our hearts go out to Jim’s wife, Cathy, their daughters, Maura and Catherine, and their loved ones. I know the Fordham family joins me in prayer for them as they grieve Jim’s loss.”

Over more than four decades in journalism, Dwyer sought to tell the stories of everyday New Yorkers and give voice to those on society’s margins, including working-class immigrants, racial and ethnic minorities, and people convicted of crimes they did not commit. Through his reporting and writing, he worked to help the public understand the impact of major issues and events, most notably 9/11, as well as the inner workings of government agencies and how their decisions affect people’s lives.

“Dwyer had boundless energy, tremendous muscular intellect, and always great empathy for people,” said Thomas Maier, FCRH ’78, an award-winning journalist and author who worked with Dwyer at The Fordham Ram and New York Newsday. “He had a lot of brain, but he had an even bigger heart.”

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, FCRH ’79, one of Dwyer’s Fordham classmates, said his passing was “a great loss” for journalism and for the people of New York.

“He was … a great New Yorker and a powerful voice for many, many years,” Cuomo said. “Jim Dwyer was about the discovery of the truth, and he was brilliant. He was hard working. He also was a poet. He had … the ability to connect with New Yorkers, to take complicated subjects, find the truth, and then communicate it to New Yorkers in a way they understood.”

Covering the Coronavirus

Last spring, in his final columns for The New York Times, Dwyer wrote about the coronavirus pandemic. In one piece, he illustrated how at the height of the pandemic in March, Elmhurst Hospital in Queens was overwhelmed, while “3,500 beds were free in other New York hospitals, some no more than 20 minutes from Elmhurst, according to state records.” In another piece, he delivered a farewell to an Upper Manhattan bar forced to shut its doors permanently: “Coogan’s was the promise of New York incarnate: multiethnic, friendly, welcoming, smart,” he wrote. “The premise of the business was the opposite of social distancing.”

And in a poetic final column, he wove together a tale of his own family history during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic with a chronicle of the thoughts and experiences of three New York City hospital workers responsible for feeding patients during the coronavirus pandemic. He related their ministrations to those of his great-grandmother Julia Neill Sullivan, who in her early 70s “marched pots of food from her hearth across a stony field on a remote peninsula along the west coast of Ireland” to keep her family alive when they were too sick to feed themselves.

“In times to come,” Dwyer wrote, “when we are all gone, people not yet born will walk in the sunshine of their own days because of what women and men did at this hour to feed the sick, to heal and to comfort.”

The Birth of a Big-City Journalist

Jim Dwyer was born and raised in Manhattan, the second of four sons of Irish immigrant parents. His mother, Mary, was a registered nurse at Bellevue Hospital, and his father, Philip, was a custodian in the New York City public school system.

His upbringing and education instilled in him a sense of justice from when he was young, his brother Patrick Dwyer, FCRH ’75, GSAS ’77, LAW ’80, said.

“I do credit Catholic school education for [his sense of justice],” he said. “He had a real conscience [and] he poked everybody else’s conscience. If you didn’t have a voice, he would figure out a way to make your story important to other people.”

He attended Loyola School, a Jesuit high school on the Upper East Side, where Patrick Dwyer said he got a taste for journalism, helping revive the student newspaper there. He said he recently received a call from the president of the Loyola School, who shared a story about a former president who complained about “what a pain” Jim Dwyer was for his work with the newspaper.

“Once a week, you know, [he would] get something out that was complaining about this injustice or that injustice, and what was a pretty fine prep school,” Patrick Dwyer said with a laugh.

He earned a full academic scholarship to Fordham, and initially intended to become a doctor.

In 1976, however, an encounter on Fordham Road changed the path of his life. Dwyer was driving when he witnessed a man having a seizure on the sidewalk. He and a few others stayed with the man and learned that he was a Vietnam veteran who had been having seizures since returning from the war.

Dwyer wrote about the experience for The Fordham Ram, and the article won a national award from the Society of Professional Journalists, due in part to his captivating lead paragraph: “Charlie Martinez, whoever he was, lay on the cold sidewalk in front of Dick Gidron’s used Cadillac place on Fordham Road. He had picked a fine afternoon to go into convulsions: the sky was sharp and cool, a fall day that made even Fordham Road look good.”

Bitten by the storytelling bug, Dwyer was helped along the path to a career in journalism by Raymond A. “Ray” Schroth, S.J., a communications professor at Fordham who became a lifelong mentor and friend, and even served as the family’s priest, presiding over weddings, baptisms, and funerals. Father Schroth, who died earlier this year, helped connect Dwyer with Maier, who was then an editor with the student newspaper.

“I would say it was probably my personal biggest contribution to journalism, getting Jim Dwyer onto The Fordham Ram,” Maier said with a laugh.

By his senior year, Dwyer was editor-in-chief of The Ram.

“I lead a double life,” he said in a 1979 Fordham marketing brochure for prospective students. “I edit The Ram and I’m majoring in science. The newspaper takes 50 hours a week of my time, so if you ask me how I manage to survive academically, I couldn’t tell you.”

Jim O’Grady, FCRH ’82, a reporter, host, and editor at WNYC, joined The Ram as a staff writer during Dwyer’s senior year.

“I remember walking into the composing room for the newspaper—back then it was made by hand, and the strips of copy that would become columns in the newspaper were hanging on the wall, because they had to dry before they could be pasted onto the board,” he said. “So you can see people’s writing styles next to each other in these strips of paper. And we were all novices, so our writing styles ranged from inept to largely overwritten. But then you saw Dwyer’s strip of writing. And it was just different. It was crisp. It was polished. It was authoritative. And you knew this guy was going on to something big. This guy already got it.”

As an undergraduate, Dwyer began dating a Fordham College at Rose Hill classmate, Cathy Muir, and they were married at the University Church in 1981, with Father Schroth presiding. The year prior, Dwyer had earned a master’s degree from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, where he said he truly knew journalism was his calling.

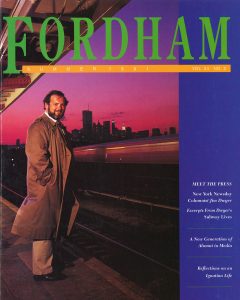

“I would come back from an assignment, my notebooks full, ready to write, and a little smile would break across my lips,” he told Fordham Magazine in 1991.

Finding His Voice Underground

Dwyer got his professional start in journalism in New Jersey, working at The Hudson Dispatch, Elizabeth Daily Journal, and The Bergen Record before taking a job at New York Newsday, where he made the most of a new assignment—subway columnist. His goal was to tell stories of everyday people and how they were affected by the world’s largest transit system, and before long, the paper was billing him as “New York’s real transit authority.”

He won a Pulitzer Prize in 1995 for “his compelling and compassionate columns about New York City.” He had also been part of a team that won the “spot news reporting” Pulitzer for its coverage of a 1991 Union Square subway derailment that killed five people.

Maier, a colleague of Dwyer’s at New York Newsday, said Dwyer’s reporting helped determine what really caused the derailment.

“It was Jim who had the sources and found out that the motorman had been drunk, and that was the front page of Newsday and that was what led to New York Newsday winning the Pulitzer Prize,” he said.

While at New York Newsday, Dwyer also became known for his work related to wrongful convictions, particularly the 1989 case of the Central Park Five, in which five Black and Latino teenagers were arrested for raping a white woman in the park. The teenagers confessed to committing the crime, but Dwyer pointed out that there was no forensic evidence linking them to the scene, and he questioned the police interrogation techniques that led to the confessions.

In one of his pieces on the case, referring to a police transcript, Dwyer wrote, “No New York jury is going to be convinced that this confession contains the language of a New York kid.” A jury convicted the teens, nonetheless. Four of them served more than six years in juvenile facilities, and one, tried as an adult, served more than 13 years in state prisons. In 2002, a convicted rapist confessed to committing the crime. DNA evidence linked him to the scene, and the teens’ convictions were ultimately vacated.

In the 2012 documentary film The Central Park Five, Dwyer reflected on the circumstances that led to the teens’ wrongful imprisonment. “This was a proxy war being fought,” he said. “And these young men were the proxies for all kinds of other agendas. And the truth and the reality and justice were not part of it.”

Patrick Dwyer said his brother pursued stories the same way he played sports in high school.

“As an athlete in high school, he was a bull,” he said. “And that’s pretty much the way he did his journalism. He would keep asking the questions until he got the truthful answer.”

Chronicling Personal Stories of Heroism and Lessons Learned from 9/11

After New York Newsday closed in 1995, Dwyer was a columnist for the Daily News, before joining The New York Times as a reporter in May 2001.

Four months later, he helped shape the paper’s coverage of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. He wrote a series of stories about objects from Ground Zero, like a squeegee a group of people used to escape from an elevator just before the south tower collapsed. And he worked with fellow reporter Kevin Flynn to chronicle in painstaking detail what happened in the twin towers from the moment the first plane hit the north tower until both towers had fallen. Their work, based on hundreds of interviews with survivors, was published as 102 Minutes: The Unforgettable Story of the Fight to Survive Inside the Twin Towers (Times Books, 2005), one of six books he would author or co-author.

In 102 Minutes, Dwyer and Flynn “stitched together a narrative that’s as compelling and suspenseful as it is excruciatingly sad,” Fordham Magazine wrote in 2005. They also documented failures of communication and missteps made by the city and the towers’ developers that came at a terrible cost on that tragic day.

Dwyer credited his science studies at Fordham with helping him tell stories that combined an understanding of technical concepts with a profound sense of human drama.

“If you’re not interested in the engineering of things … you become a servant of whatever people tell you is going on,” he told Fordham Magazine in 2015. “You’re at the mercy of experts.”

Beth Knobel, Ph.D., associate professor and associate chair for graduate studies in the communication and media studies department at Fordham, said that one of Dwyer’s biggest assets as a journalist was an ability to keep his subjects as the focus of his stories.

“He managed to keep himself almost invisible. While so many journalists sometimes make stories about themselves, Jim always kept his focus on the subject,” she said. “The way he used language and imagery spawned a lot of admiration and more than a little jealousy. I wish I had a dollar for every time I read something he wrote and thought, ‘Wow, how does someone put words together like that, with such precision and power?’”

A Commitment to Journalism That Saves and Salvages Lives

Kevin Doyle, FCRH ’78, met Dwyer when the two were undergraduates at Fordham, and they became lifelong friends, each eventually asking the other to serve as godfather to one of their children. “I was a dabbler in journalism [at Fordham]; he was a master of it even then,” said Doyle, a lawyer who has defended death-row inmates in Alabama and who led New York’s Capital Defender Office from 1995 to 2007, when the death penalty was abolished in the state.

He said that Dwyer used the “About New York” column in The Times as a platform to elevate people and causes that he felt needed attention.

“He understood the power that he had, by dint of his journalistic charge, but it never went to his head,” Doyle said. “It was always a tool rather than a prize for him.”

Doyle pointed to Dwyer’s 2012 story about Rory Staunton, a 12-year-old boy who died of sepsis, as an example of journalism that saved “thousands of lives.” Staunton went to NYU Langone Medical Center a few days after diving for a basketball and cutting his arm on a gym floor. He was feverish and vomiting, and he was discharged without being tested for sepsis. Within three days, he died. His parents, in part through sharing their son’s story with Dwyer, embarked on a campaign that eventually led New York to order hospitals “to quickly identify signs of sepsis and begin treatment.”

Five years after the initial story, Dwyer followed up and found that from 2011, before the regulations were implemented, to 2015, 4,727 fewer people died from sepsis.

“Jim wrote about this and as a result now they do [early testing], and you know, it’s saved many, many lives,” Doyle said. “He both saved lives and he salvaged lives with exoneration work.”

In late 2018, Dwyer returned to Fordham to celebrate the 100th anniversary of The Fordham Ram. The editors of the paper had invited him to serve as the keynote speaker at a centennial dinner held in Bepler Commons on the Rose Hill campus.

“If you’re a news reporter, you need to hope for humility,” Dwyer said that night. “And own your own mistakes.”

Knobel said that Dwyer’s address that night was a “love letter” to journalism.

“As in his reporting and column, Jim made it clear to the alums and young reporters there that journalism is really about telling other people’s stories and is one of the greatest ways to spend one’s life,” she said. “The talk was charming and self-effacing and powerful, just like Jim’s work.”

A Generous Colleague, Friend, and Mentor

Maier said that Dwyer was willing to help fellow journalists, whether by recommending a source for a story or even sending a story their way. He recalled that about two years ago, he got a call from an attorney representing a man named Keith Bush, who had been convicted of the murder of a Long Island teen in 1976, but always said he was innocent.

Maier worked on the story for about a year, publishing a 16,000-word investigative report on the case and putting together a documentary on it—all without telling Dwyer, because he didn’t want his friend and former colleague to write about it first.

“I reported out the whole story, that’s almost an entire year, fearful that Dwyer would scoop me on the story for The New York Times,” he said.

Only after Bush was exonerated, on May 22, 2019, did Maier find out that Dwyer was the one who told the lawyer to call him.

Doyle said that outside of work, Dwyer was also known as a loyal, caring, dedicated friend.

“He was always eager to help—he’d drop whatever he was doing. He was a problem solver, inside his family and to his friends,” Doyle said.

O’Grady said that while Dwyer’s passing is a loss for journalism and Fordham, his work and teaching live on in the young journalists he mentored.

“We’re losing a legendary reporter, who was still in his prime, but who spent countless hours mentoring future generations of journalists,” he said. “He’s still with us in the many Fordham students he spoke to and inspired, and people all across the profession who he helped and encouraged.”

Patrick Dwyer said that his brother and his voice will be missed.

“We were extraordinarily proud of him,” he said. “I spoke to a friend yesterday … and I said, ‘You know what, I actually feel that we got it right. The esteem we held him in was apparently shared by everybody else.’”

He is survived by his wife, Cathy Dwyer, FCRH ’79; his two daughters, Maura Dwyer and Catherine Elizabeth Dwyer; and his three brothers, Patrick Dwyer, Phil Dwyer, FCRH ’80, and John Dwyer.

]]>