Photos by Argenis ApolinarioStudents heading to the Walsh Family Library to study for finals will be met with a little something extra as they pass through the exhibit hall: a dead Snow White and a swarm of plastic ants.

Break Out—You Can Do It! and Is it a Crime?, the pieces featuring the Disney princess and the insects, are two of 10 pieces that comprise “Gender Comics,” a new art exhibition that runs through Dec. 13.

The exhibit features drawings, comic books, comic strips, zines, prints, web comics, animated comics, and comics objects. All were done by women art students from Austria who were part a partnership between the University of Art and Design Linz (Austria) and Fordham’s German program. The two groups joined forces during the COVID lockdown in a team-taught COIL (Connecting Research to Collaborative International Learning) course that brought together students from either side of the Atlantic Ocean.

For that class, Susanne Hafner, Ph.D., professor of modern languages and literatures, asked the Fordham undergraduate students to work with the Austrian students, enrolled in a class about comics taught by Barbara M. Eggert, Ph.D., assistant professor of art at the Linz university. Together, the students conducted interviews in German with artists who had previously displayed their work at the NEXTCOMIC Festival in Linz in 2020. Their interviews will be published in the We are family! Kritische Perspektiven auf soziale Mikrostrukturen in Comics, in the journal deGruyter.

A Reunion in New York

Once international travel resumed, Hafner and Eggert arranged an in-person reunion with the students. Five of the Austrian students arrived in New York last weekend to help set up and give tours during an opening reception on Dec. 1, with plans to stay for a week at locations around the city.

“What we were dreaming about was that after a semester together online, we would actually be able to visit each other. So this is the visit from the Austrians for them. Now we’re working to get the Fordham students who are part of this publication to visit the next big comic exhibition in Linz,” she said.

Most of the pieces had been shown in Austria before, some at the NEXTCOMIC Festival in Linz in 2021 and 2022. But several were created just for the Fordham exhibition.

Playing on Gender Stereotypes

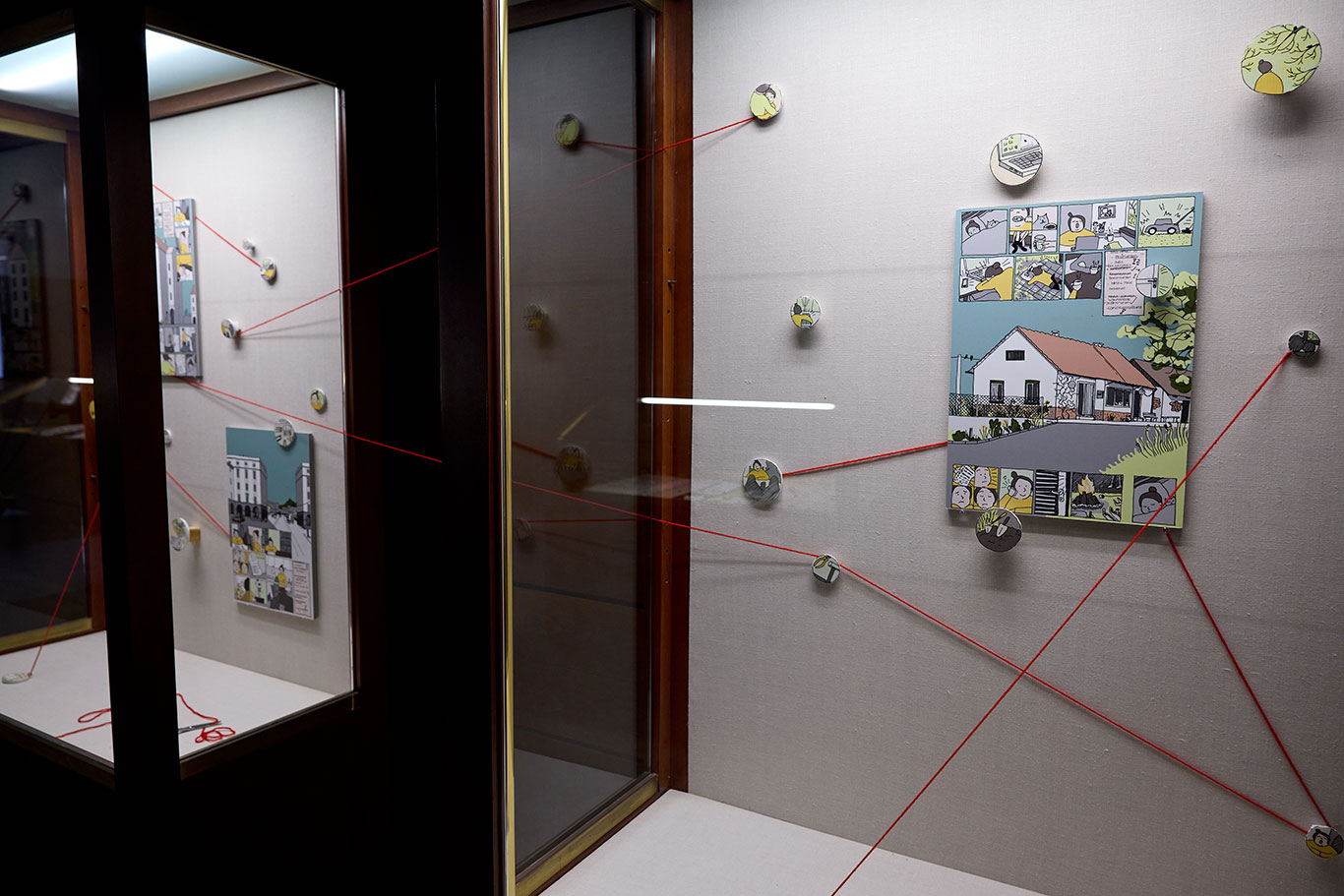

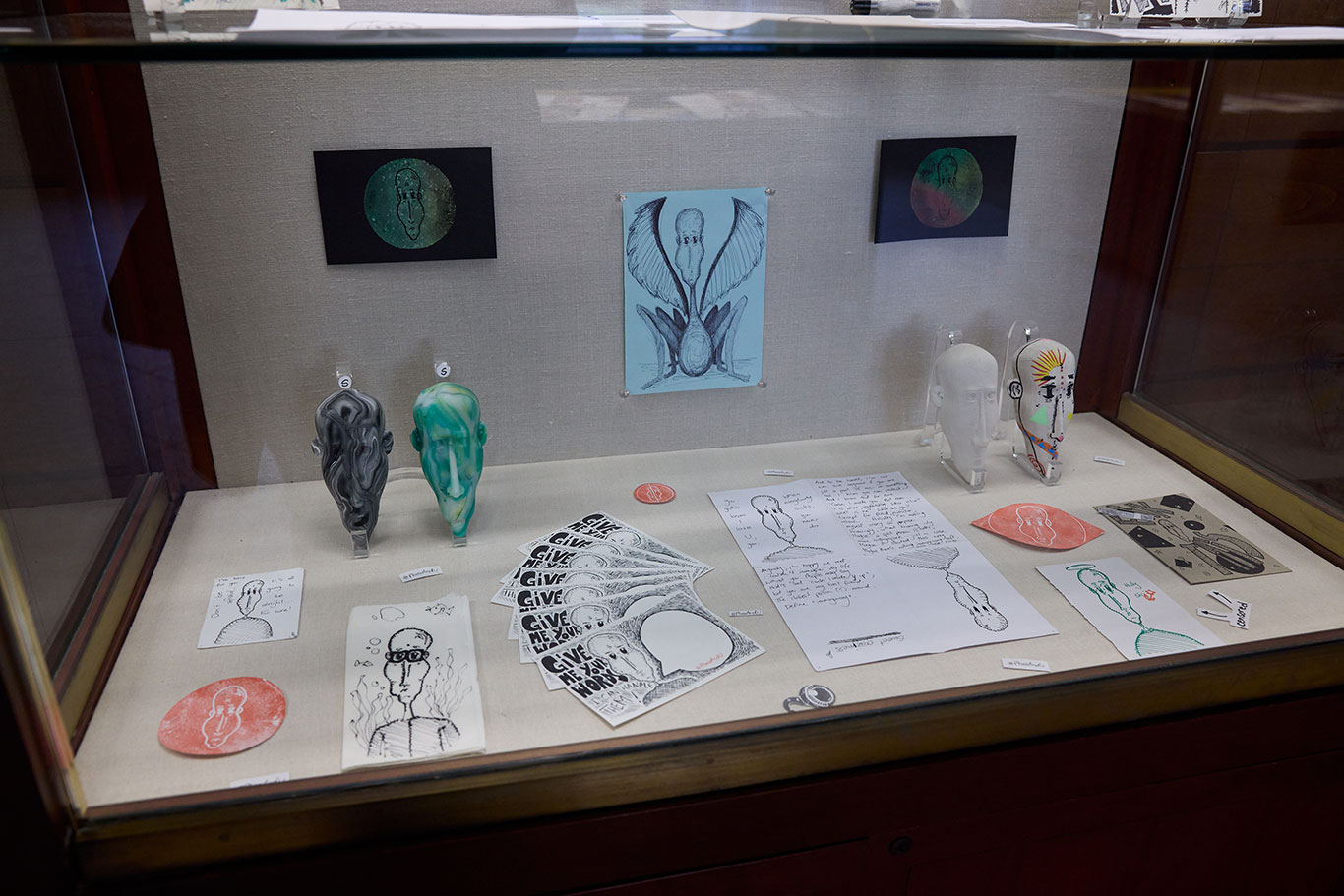

All of the pieces in the exhibit deal with gender-related stereotypes. Eggert said that the goal is to push the boundaries of what could be described as a comic, and show how the form, which has historically been created by and for a male audience, has been embraced by women. In Lisa’s Odyssey, for instance, artist Lisa Marie Gmeindl connected various roles she inhabits, from student to girlfriend, daughter, partner, and homeowner, to each other through red string that leaps from one display case to another. In Inside the U-NIVERSE, the artist Phea displays nearly two dozen drawings, sculptures, and objects that build on interpretations of an androgynous face.

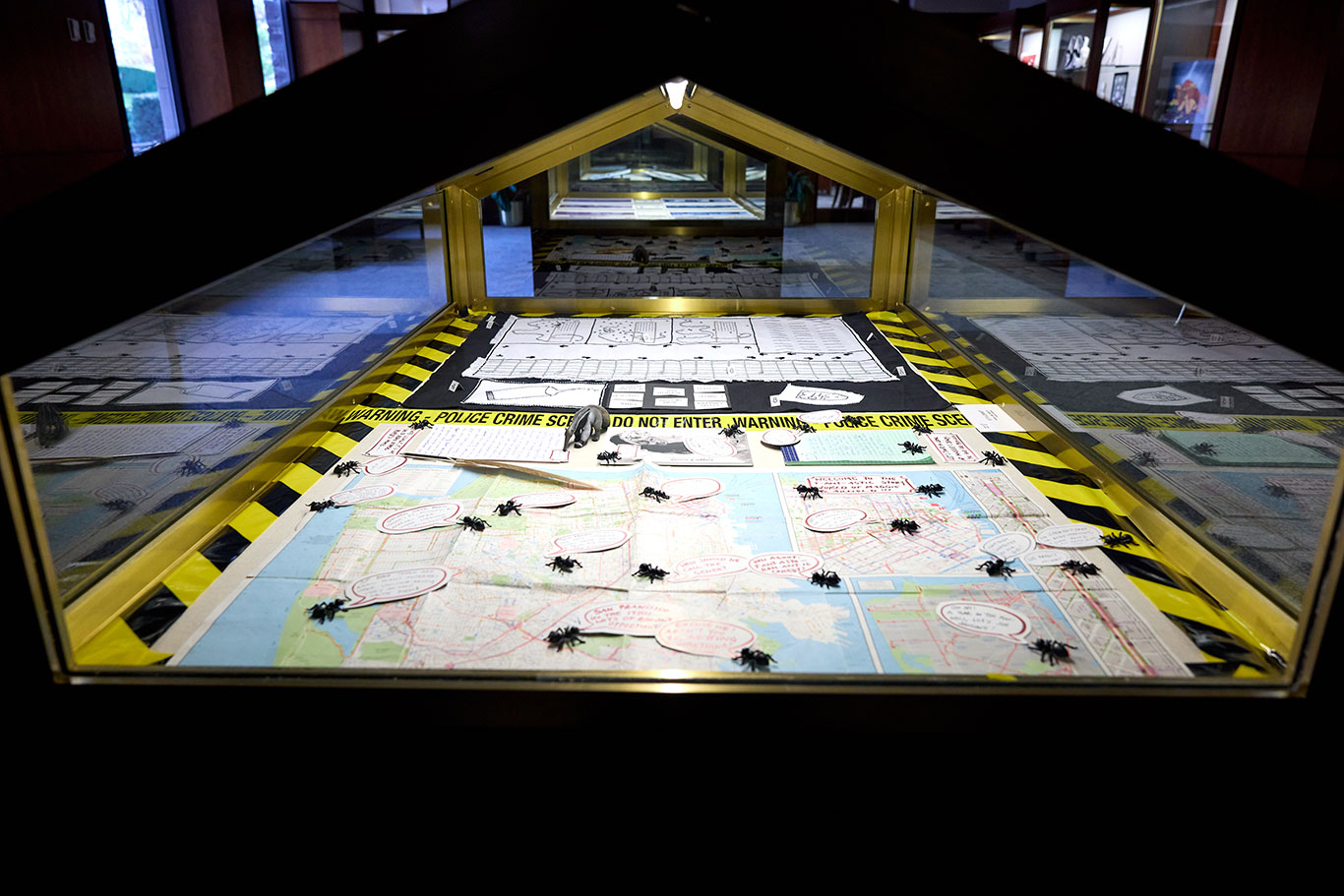

Break Out—You Can Do It! criticizes the ways Disney princesses promote the social stereotyping of gender roles, and makes the case that they should not wait for their prince to rescue them. Is it a Crime?, a sprawling installation evocative of graphics novels, combines two perspectives on trans-species interactions, in a scenario that blends 1990’s era San Francisco with a fantastical parallel universe.

Much attention has been given to the space as well.

“We decided that it’s much more interesting to show these boundary-pushing comic objects in a very formal setting, because you have this tension between the formal setting and what you would expect to see in it,” Eggert said.

“You have, for example, plastic ants in Is it a Crime, or the ribbons crossing over in Lisa’s Odyssey. It’s more interesting to work against the structure here than at a gallery, where you can do pretty much anything.”

The five visiting students helped organize an opening reception where—owing to prohibitions against alcohol in the space—drawings of “drinks” were offered up. Eggert is also using the opportunity to study the library’s recently acquired selection of Catholic comic books.

Speaking Through Pictures

Anja Wittmann, a recent graduate of the Austrian University of Art and Design who contributed the 12-panel piece Better Earth, said she was drawn to the comic form because she likes telling stories, but doesn’t consider herself a good writer.

“Emotions are much easier to carry in a picture than in a text,” she said.

“One thing that’s great is it’s universal. My comics have a few words in them and they’re in English, but someone who doesn’t speak English could also understand it.”

Lisa Baumgartner, a senior at the Austrian university whose three-panel Perspectives is arrayed like a triangle under a display case, said the sheer number of styles on display show how easy it is for anyone to take up the form.

“I think it’s a good way to motivate other people to scribble around, and not always feel like they have to do something highly professional. Just to try to sometimes speak in pictures,” she said.

“We are doing this all the time with emojis on WhatsApp or whatever, but we are not doing this in daily life. Why not?”

Exhibits marked with a sticky dot are available for sale, with proceeds going toward the purchase of comics for the library that address aspects of diversity including age, class, dis/ability, race and gender. Bids start at $5, and can be submitted via e-mail to Eggert at barbara-margarethe.eggert@ufg.

The presentation, “Abbot Ellinger of Tegernsee: In Exile, in Pain and in German,” given by Susanne Hafner, Ph.D., focused on details about the abbot that he himself included in one of his manuscripts. Hafner, an assistant professor of German, said she learned much about Ellinger through the medieval text, known to scholars as HRC 29.

Speaking from the O’Hare Special Collections Room in the William D. Walsh Family Library, she explained that the abbot had at one point been banished to Niederaltaich, a Benedictine monastery on the East Bavarian frontier where there was little to do but mill about the library. The reasons for his banishment are unclear, but are said to be linked to his irascible nature.

A possible explanation for his irritability may appear the margins of the Latin-penned HRC 29, Hafner said. It was there that Ellinger wrote, in his native language of Old High German, prescriptions for ailments such as stomachaches, headaches, dropsy and no less than seven different treatments for dolor testiculorum.

It is not known whether he followed all of them, as they often included hazardous substances, she said. But the fact that he used a translation that was unlikely to be mistaken showed how serious he was about the remedies.

“Ellinger, a highly educated man and abbot of one of the cultural centers of Carolingian Europe, was well versed in Latin and Greek, both of which he used in HRC 29,” she said. “But when the issue was personal rather than academic, he felt the need to verify his vocabulary.”

Although HRC 29 mostly included copies of books that had been destroyed when Tegernsee was sacked by Hungarians in 907, Hafner noted that, like Ellinger’s fellow scribes, he made a sport of adding notes—often written in code—using runes, Greek letters, acrostics, or glosses scratched into the parchment.

“Claiming authorship of his codex seemed to have been particularly important to him. In addition to the colophon, he left his name in the margins, twice, in code,” Hafner said.

Analyzing writings such as these help scholars better understand Europe in its pre-Christian, pagan heritage.

“Talking about this manuscript is a homecoming in more ways that one for me, because it was written in the monastery of Niederaltaich, which happens to be right next to the little town in the Bavarian Forest where I grew up,” she said.

Hafner found the medieval document in the archives of the University of Texas at Austin, where she worked before joining the Fordham faculty last year.

“I am still humbled by this act of divine providence, which had the codex written—for me, as I would like to think—a thousand years ago, then safely tucked away: first in a Benedictine library; then in a private collection; and then deep in the heart of Texas.”

]]>