On June 10, 1967—a time of mass protests against the Vietnam war and rising violence in the struggle for racial justice—the 41-year-old U.S. senator from New York reminded Fordham graduates that they were entering “a world aflame with the desires and hatreds of multitudes.”

He urged them to hear the voices of “the dispossessed, the insulted, and injured of the globe,” to heed their own revolutionary responsibilities, and to remember the difference that one person can make. And he quoted from his June 1966 “Day of Affirmation” address at the University of Cape Town during the height of apartheid in South Africa:

Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

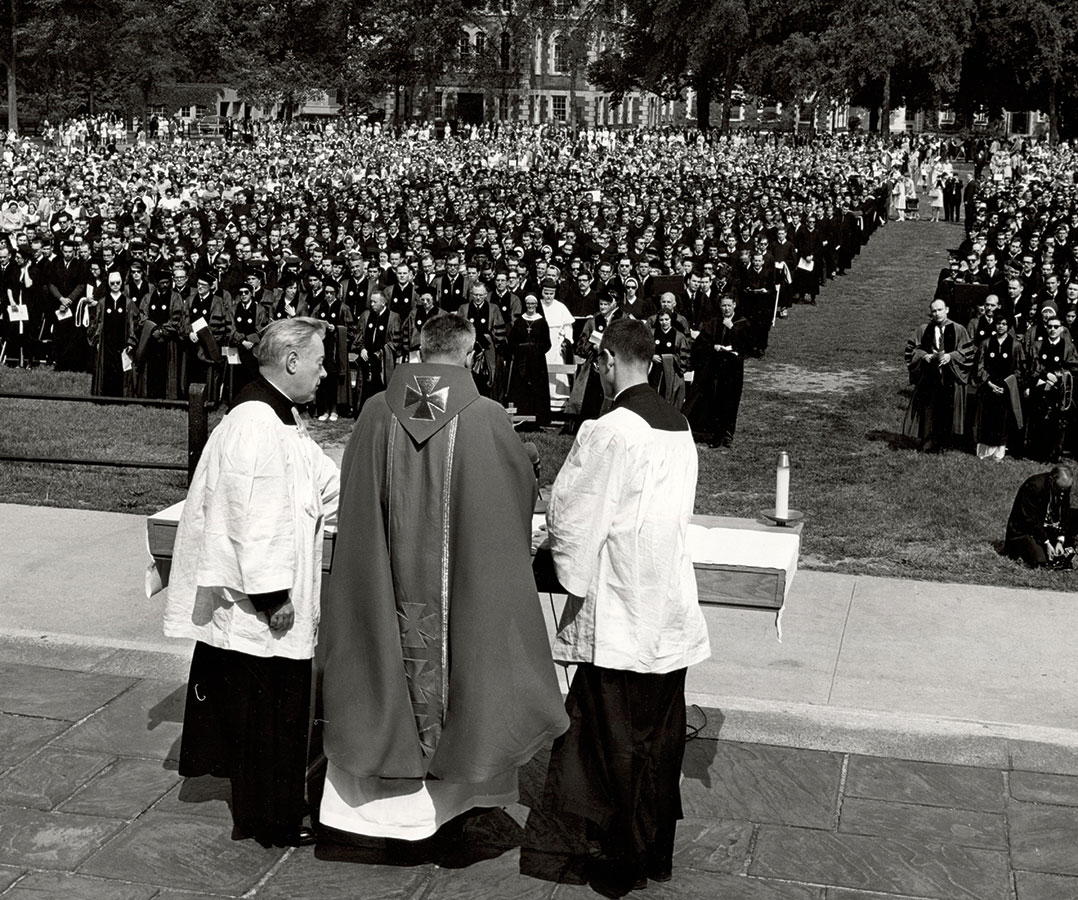

“It was electrifying,” recalls William Arnone, FCRH ’70, who heard the speech from the back of Edwards Parade. Later that year, Kennedy’s staff came to Fordham to recruit students. “They said, ‘You can study politics or you can do it,’” Arnone says. “Next day, I showed up. I was hooked.”

He and several other Fordham undergraduates worked as constituent case aides in the senator’s New York office, fielding inquiries from New Yorkers in distress.

In the four-part Netflix series Bobby Kennedy for President, released last year, Arnone describes taking calls from single mothers in Harlem who struggled to protect their children from rats—and to get their landlord to help.

“I would get the name of the superintendent and the landlord,” Arnone says in the film, “and I would call them up: ‘This is William Arnone, I’m calling on behalf of Senator Robert F. Kennedy. There are rats in Mrs. Smith’s apartment, eating her children’s toes. What are you going to do about it?’ And I would get the same answer, ‘You mean Robert Kennedy cares about Mrs. Smith’s kids?’ ‘Yes.’

“I would get the name of the superintendent and the landlord,” Arnone says in the film, “and I would call them up: ‘This is William Arnone, I’m calling on behalf of Senator Robert F. Kennedy. There are rats in Mrs. Smith’s apartment, eating her children’s toes. What are you going to do about it?’ And I would get the same answer, ‘You mean Robert Kennedy cares about Mrs. Smith’s kids?’ ‘Yes.’

“Invariably I get a call the next day: They have an exterminator, no more rats. ‘Thank God for Mr. Kennedy.’”

In mid-March 1968, Kennedy launched his campaign for president, running on a platform of economic and racial justice, and an end to the war in Vietnam. “We all fed him things to use in the campaign,” recalls Arnone, who was ecstatic when Kennedy shared his story about the rats during a campaign speech. “But then he would send me notes and say, ‘Good job, you helped her. But we have to have the solution that’s systemic.’”

Kennedy’s campaign lasted less than 90 days. Shortly after winning the California primary, he was assassinated in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. He died on June 6.

Two days later, Arnone was at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan for Kennedy’s funeral Mass, after which he rode on the private train that carried Kennedy’s body from New York City to Washington, D.C., for burial in Arlington National Cemetery.

“It was just a nightmare, but it was poignant” seeing the hundreds of thousands of mourners who lined the tracks to bid Kennedy farewell, he said.

Arnone went on to a career focused on the elderly and retirement issues. He is the chief executive of the National Academy of Social Insurance, a Washington, D.C.-based nonpartisan think tank, and he remains inspired by Kennedy.

“He was fierce, passionate, and understood vulnerability in a way that was authentic, and it changed my life. His whole goal was to bring people together and try to avoid class warfare, avoid violence,” Arnone says. “To me, that’s the message for today.”

With just 5% of the world’s people but more than 20% of its prison and jail inmates, the United States clearly has an incarceration problem—and experts say it will take far more than federal legislation to truly fix it.

“Mass incarceration is not just a huge policy failure. It’s a humanity failure,” says John Pfaff, Ph.D., a professor at Fordham Law School and author of Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform (Basic Books, 2017).

Pfaff has shifted the debate about criminal justice reform by challenging the standard story about the runaway growth of the U.S. prison population since the early 1970s. The primary cause, he argues, is not the war on drugs and the proliferation of nonviolent offenders in prison but the unchecked power of local prosecutors and how we respond to violent crime.

Part of the solution is to give prosecutors incentives and tools to take a less punitive approach, Pfaff says. He has also called for more public consideration of the prison system’s impact on people and communities. “We spend $50 billion a year on running the prison system,” he says. “But we can’t tell you what we’re really spending in terms of the actual human costs.”

In prison, people contract diseases like HIV and tuberculosis at a rate 10 to 100 times higher than outside the prison system, he says. They suffer physical and sexual abuse, develop mental health problems, and have a hard time earning enough money when they’re released. Their families earn less and suffer from mental health trauma as well, and their children face a greater risk of going to prison. “And despite doing this for 40 years,” he says, “we’ve just never estimated those costs, and I think we haven’t measured them, because at a very real level, we don’t care.”

A change in attitudes is needed, he says. “How do you get people who aren’t in the prison system to care about those who are? Until we make that move, we’re going to really struggle to not be the world’s largest jailer.”

Prevention Before Incarceration

Like Pfaff, Anthony Bradley, Ph.D., GSAS ’13, decries overly punitive approaches to criminal justice, and points to a host of additional causes of mass incarceration: class, poverty, race, family breakdown, and mental illness.

In his book Ending Overcriminalization and Mass Incarceration: Hope from Civil Society (Cambridge University Press, 2018), he argues for taking a comprehensive, long-term approach to safeguarding the well-being of people who are at a higher risk of getting in trouble with the law. Everyone can help in this effort, he says. “This is largely an issue about who we decide has human dignity and who does not.”

During a lecture at Fordham’s Rose Hill campus last November, he explained that the book had its beginnings in a class he took while earning a master’s degree in ethics and society at Fordham. He was “blown away,” he said, after learning about the links between young children developing post-traumatic stress disorder and ending up in the juvenile justice system later on.

“I realized that we’re not just locking up bad kids, we’re locking up hurt kids. It completely changed the course of my career,” said Bradley, a professor of religious studies and director of the Center for the Study of Human Flourishing at The King’s College in Manhattan.

The federal government’s war on drugs since the early 1970s can’t be the main cause of mass incarceration, he said, because 90% of all inmates are in state prisons, and of those, only 17% are drug offenders. In part because of a focus on federal prison data, “we get the story wrong,” he said. “If we don’t get the story right, we’ll get the solutions and interventions wrong.”

Part of that story, he said, is society’s views toward the poor. “Here’s a tough social fact in this country: We resent poor people in America regardless of their race,” he said. “We’ve used the criminal justice system to remove them, the poor, from civil society.”

And those who enter the criminal justice system are “overwhelmingly poor,” he added. With no money to pay legal bills, they have to rely on overburdened public defenders, and their poverty is compounded when their prison records create a barrier to employment, he said.

Caring for the Whole Person

Last December, the federal government enacted the First Step Act to reform criminal justice and reduce prison crowding, following on many state governments’ legislative efforts over the past decade.

While the new law is commendable, deep and meaningful change can only come from convincing the nation’s local prosecutors and police chiefs to do things differently, Pfaff says. “We tend to focus on the federal government as what is going to fix the problem,” but solutions must come on a “city-by-city, county-by-county level.”

In his talk at Rose Hill, Bradley also called for grassroots, “upstream” efforts to provide emotional, social, psychological, and moral support to children before they wind up in trouble with police.

“As long as we have hurting children, we’re going to have violent children,” he said. “We need to invite more players to the table. Yes, we need lawyers; yes, we need judges. … We also need coaches and teachers and business owners and cousins and aunts and uncles and community nonprofit leaders to offer the sorts of interventions that address the whole person.”

Bringing Ignatian Spirituality to the Incarcerated

Public defender John Booth, GRE ’14, has taken an interdisciplinary approach to the problem. After a decade representing people charged with serious crimes in Hudson County, New Jersey, he felt he was burning out, tired of watching clients repeat the cycle of incarceration.

“Why do I find myself representing the children of former clients?” he wondered. “When will all of this hurt end? Most importantly, where is God in all of this and why am I a witness to such horror?” He examined his own motives for becoming a public defender. “I knew I cared for them and was always fighting for them,” he says, “but I didn’t realize just how deeply they had touched me.”

Booth recognized there was a spiritual element to addressing the problems of criminality, mass incarceration, and recidivism. But there were limits to what he could do as a lawyer, ethically and practically. He knew it was inappropriate to discuss matters of faith with his clients, that “melding the roles of attorney and minister can add another injustice upon the accused person,” as he put it, but he also had no plans to give up his day job.

So in 2009, after he and his wife lost a child to stillbirth, Booth began further exploring his Catholic faith. He took “the Ignatian retreat in daily life,” a way to complete the 500-year-old Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola over a period of eight months instead of during an intensive 30- day retreat in solitude. Afterward, he felt that undertaking the Spiritual Exercises—a mix of meditations, prayers, and contemplative practices—could prove as valuable a healing process to incarcerated people as it was to him.

That thinking led him to Fordham’s Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education, where he completed a master’s degree in religious education in 2014. His thesis explored how the exercises could provide emotional support and spiritual freedom to inmates and help them transition to society after release.

“A lot of [inmates]will say that they can’t do this on their own,” he says.

Bringing Guidance Behind Prison Walls

After completing his master’s degree, Booth met Zach Presutti, S.J., a Jesuit scholastic and a psychotherapist with an interest in prison ministry. Presutti read Booth’s thesis and realized it contained the kind of spiritual guidance he wanted his new nonprofit, Thrive for Life Prison Project, to provide for the incarcerated.

Booth created a brochure for Thrive for Life volunteers providing Ignatian spiritual direction to inmates—and he began volunteering with the group as a spiritual director. Several times a month, he visits with inmates in New York—at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, the State Correctional Institution in Otisville, and the Manhattan Detention Complex, also known as the Tombs—and leads them through an abridged version of the Spiritual Exercises, providing a safe environment that fosters self-expression.

“They can just kind of let go and be themselves,” he says. “And as time goes on, you see them expressing more and more and more, individually and collectively.”

Breaking the Cycle, Building Relationships

Thrive for Life’s spiritual directors stay in touch with the group’s participants. One former inmate now works full time with the group. Many other former inmates gather once a month with volunteers, friends, and family at the Church of St. Francis Xavier in Manhattan, where the organization is based. And Thrive for Life recently opened Ignacio House, a Bronx residence for people recently released from prison.

Meanwhile, Booth says his workload as a public defender was made more manageable by bail reforms New Jersey instituted two years ago, which include new standards for deciding whether an inmate poses a danger to society. His time at Fordham gave him new perspective on his day job—and on practicing his faith in service of others. “Courses were geared toward trying to live out your faith in the modern world, with constant interaction with the real world,” Booth says. “Fordham made me into the best spiritual director that I could be.”

College in a Maximum Security Prison

Since 2015, Steve Romagnoli, FCRH ’82, a playwright, novelist, and adjunct professor of English at Fordham, has been helping to bring the transformative power of education to women in prison. On a Thursday evening near the end of the spring semester, he led his students through the moral ambiguities of Ruined, Lynn Nottage’s 2009 Pulitzer Prize-winning play about the wages of war in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The scene in the classroom was reminiscent of an undergraduate seminar on any college campus, with one exception: Students wore the green uniform of inmates at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, the only maximum security women’s prison in New York state.

Like all guests at the prison, Romagnoli enters the compound through a trailer-like structure that separates the visitors’ parking lot from the prison buildings, which are ringed by metal gates topped with razor-wire coils. He passes through a security checkpoint carrying only his car keys, driver’s license, and notes for class.

“It’s like going in and out of a concentration camp, with the walls and the wires,” he says. “But sitting in the room and watching them talk and laugh and banter, you could be anywhere.”

Romagnoli’s students range in age and experience. For one woman, the course—Social Issues in Literature—is her first taste of college; for another, it’s the next-to-last class needed for her bachelor’s degree in sociology.

“Steve is always in demand,” says Aileen Baumgartner, FCRH ’88, GSAS ’90, the director of the Bedford Hills College Program. Overseen by Marymount Manhattan College, it offers courses leading to an associate’s degree in social sciences and a bachelor’s degree in sociology.

“Students really get a lot from his classes. I don’t know how he does it—I’ve said, ‘Really, Steve? You think they’re going to get through all this in a semester?’ Somehow or other they do.”

‘Students Have to Feel There Is Love’

At Fordham, Romagnoli teaches a similar course on ethics and literature, albeit with a more sensational title: Murder, Mayhem, and Madness. In both settings, students focus on “moral dilemmas and ethical questions that confront us throughout our lives,” he says.

“The Fordham students have great things to say, but they’re initially a bit shy,” he says. “At the prison, sometimes you’ve got to pull them together, but they’re totally engaged, and they say what they’ve got to say.”

Romagnoli began his career as an educator at P.S. 26 in the South Bronx during the mid-1980s, not long after earning a bachelor’s degree in English at Fordham. He later earned an M.F.A. in creative writing at the City College of New York.

For 15 years, he was an itinerant teacher for the New York City Department of Education, working with students in their late teens to early 20s at drug rehabilitation facilities, homeless shelters, and halfway houses, among other locations. “I would go in and teach a lesson and go out,” he says. “Engage them, that was the whole thing. You’ve got to engage them.”

No matter where he teaches, his approach is essentially the same. “Students have to feel there is love there—not love love, but a deep respect. And if they come to the conclusion, consciously or unconsciously, that you have that deep respect, then it allows you to be as demanding as you want to be.”

Baumgartner notes that all of the students at Bedford Hills are required to work during the day—as porters or clerks or sweeping floors, for example. And they complete their coursework in the evening and early morning hours without the benefit of internet access.

Like Romagnoli, Baumgartner went to Fordham, where she earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English. She started teaching at Bedford Hills in 2001, when she was a professor at Mercy College, and became the director of the college program in 2002.

“I had never given any thought to prison education programs,” she says. She recalled that on her first day of class, “all the students were looking at me, sizing me up, and they asked, ‘Why are you here?’ ‘I was asked to teach, and so here I am.’”

Baumgartner’s straightforward answer satisfied the students, who, she realized, didn’t want to “hear someone come in and talk to them about high-minded ideals.”

She notes that prison education programs reduce recidivism and create better employment opportunities for former inmates. “Whether you’re a prisoner or not, you have many more options in life if you have a college education. And if you are a prisoner and you have a felony conviction on your record, when you return to the outside, it’s very nice to have a college degree on your record too.”

Students also benefit in ways that are less tangible. “They gain a deeper understanding of the forces that shape communities, that shape themselves, that shape their children,” she says. “They learn that they have the power to act in positive ways in their communities that perhaps they didn’t feel they had before.

“And then there’s that ripple effect,” she adds. “They’re concerned with their children going to college. Now it matters to them.”

Regarding costs, she says “the college program is not as expensive as keeping people imprisoned.”

Approximately 150 women—or roughly 25% of Bedford Hills’ standing inmate population—are enrolled in the college program, Baumgartner says. And every spring, the program hosts a graduation ceremony. This year, she says, six women earned a bachelor’s degree and 14 received an associate’s degree.

‘A Fairer, More Effective Criminal Justice System’

Inmates at Bedford Hills have benefited from college education programs for decades. “Mercy College had a college program there until the tough-on-crime bill was passed,” Baumgartner says, referring to the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, which eliminated Pell Grants for inmates.

“Across the country, a lot of colleges, including Mercy, closed their prison programs in the mid-1990s because they just couldn’t afford it” without federal funding, Baumgartner says. The number of U.S. prison college programs dropped from about 300 to just a handful.

At Bedford Hills, a coalition of community members designed the college program, which is funded by private donors and grants. Since it began in spring 1997, more than 200 women have earned college degrees there.

And since 2016, it has also received support through the Department of Education’s Second Chance Pell Pilot program, a three-year experiment that aims to “create a fairer, more effective criminal justice system, reduce recidivism, and combat the impact of mass incarceration on communities.”

Inmates who take part in prison education programs are 43 percent less likely to return to prison in three years, compared to those who don’t take part, according to a federally funded RAND Corporation study from 2013, the education department noted in announcing the program.

Baumgartner credits the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision for supporting higher education programs in prisons, including the one at Bedford Hills. “These programs sometimes tax their resources,” but the department understands their importance, she says.

Romagnoli talks with his Fordham students about his work at Bedford Hills, and about mass incarceration and criminal justice reform. “It resonates strongly with them,” he says. “And it’s something that’s really come into the public consciousness [in recent years]; the ball’s rolling a little quicker.”

‘Knowledge Is Power’

Back in the classroom at Bedford Hills, after a heavy but lively discussion about Ruined, Romagnoli gives the students a brief break before moving on to Zora Neale Hurston’s 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Asked to reflect on the course, which also includes discussion of philosophers from Socrates to Simone de Beauvoir, students say they’ve learned that “knowledge is power.” They say that “perception plays a big role in how people judge people,” that the readings have helped them “gain different perspectives,” and yet the class “brings a unity, even if we agree to disagree.”

“You learn more about yourself, about your ethical system, and you question the things you do,” says one student. “I am one class away from a B.A. When I leave here, I will always question the morality of a situation.”

—By Chris Gosier, Adam Kaufman, and Ryan Stellabotte

]]>A man answered the knock at the door. The agents didn’t know that this was their suspect. After a tense exchange with the agents, he pulled out a revolver and shot and killed two of them, Anthony Palmisano and Edwin Woodriffe, GABELLI ’62. He fled the apartment through a window, and city police and FBI agents captured him a few hours later. The murder of the two agents still resonates. Both were under 30, part of a tight-knit cohort of young agents in the FBI’s Washington field office, some of whom vividly recall the events of that day, January 8, 1969. And the killings were shocking for another reason. Woodriffe, 27 at the time, became the first black FBI agent to die in the line of duty.

For burial, he was brought back to his native Brooklyn, back to the city he loved, where he had worked his way through Fordham before launching his career in government service.

This April, the story of the earnest, witty agent who died too soon came back into the spotlight as the city honored him by making his name a fixture on the urban landscape. In a well-attended ceremony on a Brooklyn street corner, in the heart of the neighborhood where Woodriffe grew up, his immediate family spoke in remembrance of a radiant young man whose spirit seemed, somehow, to be present still.

A Child of Immigrants

Like so many New York stories, Edwin R. Woodriffe’s begins with immigration—his parents came to America from Trinidad when they were either in their teens or barely out of them, said Woodriffe’s daughter, Lee Woodriffe, of Lithonia, Georgia. They ran a dry cleaning shop in the struggling Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, getting up early every day—“no time off, no sick days, no nothing”—and instilling a strong work ethic in their children, she said.

The youngest of three boys, Woodriffe helped out at the dry cleaner’s after school and doted on his parents, Lee Woodriffe said. He was an altar boy at nearby St. Peter Claver Church, where he met his future wife, Ella Louise Moore, during Christian confraternity classes.

After graduating from Brooklyn Preparatory School, he earned a degree in accounting at Fordham’s City Hall Division at 302 Broadway, where he was vice president of the philosophy club. He paid his way by working as a police cadet and as an elevator operator at Macy’s, his daughter said. Upon graduation, he and Ella were married, and they had two children, Lee and her brother, Edwin Woodriffe Jr. Lee was only 5 when her father was killed, but learned from others what he was like. He was a jazz lover who would sometimes play his saxophone on the roof of the building where the family lived, she said. A voracious reader interested in religion and philosophy, he was a deep thinker, which was apparent from his conversation and his humor, she said.

The idea of working in law enforcement had taken hold when he was young; he admired his older brother for being a New York City police officer. After working for the Treasury Department in enforcement, he joined the FBI in 1966. Sometimes he would sign letters “Eliot Ness,” Lee said, describing her father as “really good-natured, and just always cracking a joke.”

In the FBI’s Washington, D.C., field office, he was low-key and decisive, “a very classy individual” who was courteous toward crime suspects, said Ed Armento, a retired agent who trained under Woodriffe for a week.

Lee Woodriffe said her father was one of only a handful of black FBI agents. Retired agent Robert Quigley, GABELLI ’62, recalled working with three black agents besides Woodriffe in the Washington field office. Given Woodriffe’s talents, “there is no doubt in my mind that [he]would’ve been one of the top FBI executives had he lived,” Quigley said.

He recalled a story of solidarity against racism that was told to him: When Woodriffe was an FBI trainee in Washington, D.C., he and his classmates went to suburban Maryland to rent apartments, but they all pulled out of a pending housing contract when told Woodriffe would be barred. “The other agents were aghast,” Quigley said, so they sought housing elsewhere.

A Tragic Day

Quigley remembers the day when agents learned of a bank robbery by Billie Austin Bryant, an escaped federal prisoner. Woodriffe, Palmisano, and another agent went to the apartment where they had heard Bryant’s wife or girlfriend lived, said Quigley, citing reports prepared afterward. The agents couldn’t have known it was Bryant who opened the door when they knocked—“They have no photograph, no idea what he looks like,” Quigley said. “Back in those days, all we had were radios in the car. There was no way to send a photo.”

Bryant told the agents the woman they were seeking wasn’t there. When they asked to come in and wait for her, he refused and started to close the door. Woodriffe put his foot in the door to stop him, and Bryant pulled out his revolver. Woodriffe and Palmisano never got a chance to pull their firearms, said retired agent Charles Harvey, who tried to revive the two agents soon after.

Bryant surrendered to a police detective six hours later, after being tracked down to an attic in a building where someone had reported noise, said Quigley, who was there when Bryant was captured. Bryant was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences with no chance of parole.

The 50th anniversary of the two agents’ deaths was commemorated in Washington in January by the bureau’s Washington field office and the Society of Former Agents of the FBI. Harvey spoke at the event. “Our job is to never forget,” he said.

Meanwhile, in Brooklyn, another remembrance had taken root.

A Street Renamed

St. Peter Claver Church sits at the intersection of Jefferson Avenue and Claver Place in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Lee Woodriffe spearheaded the two- year effort to have the City Council co-name the segment of Jefferson Avenue starting at that intersection in honor of her father, hoping to keep him present in a part of the city that was important in his life, she said.

“I did not want his final resting place in people’s minds to be in Cypress Hills Cemetery,” she said. “It’s very important to me that [his story]come full circle, but come full circle in the right way.”

The co-naming sends an inspiring message, she said. “Here is somebody who came from an impoverished area, odds stacked against him, but through perseverance and diligence and having integrity and wanting to do better, rose up through the ranks and really made something of himself. It’s a story of hope, and what you can become.”

On April 26, FBI Special Agent Edwin R. Woodriffe Way was formally christened in a ceremony attended by FBI agents, New York City police, city officials, clergy, and friends and members of Woodriffe’s family, including his widow, Ella Woodriffe.

“There’s a saying that hatred corrodes the vessel it’s carried in, but today I have no hatred,” she said. “I speak with heart-filled joy and thanking God for allowing all of us to be here in attendance as a testament to my husband’s memory.

“His story began right here at St. Peter Claver Church,” she said. “Edwin went to school here. He went to church here. He was an altar boy here. We met as teenagers here. … We were married here, we had two children, and lastly, he was funeralized here. He will be forever remembered in our hearts.”

Edwin R. Woodriffe Jr., who was 6 when his father died, lacks vivid memories of him. “There are photos and stories from friends and family, but the nuances are lost,” he said at the ceremony. “What was his favorite color? I don’t know. I have one of his high school essays on basketball. Were the Knicks his favorite team? I don’t know, and if I did, I don’t remember.

“But he got a B+, by the way, on the paper,” he said, to laughter.

“The thing I remember most is the idea of him represented inside the family,” said Woodriffe, whose mother got help from extended family in raising him and Lee. “I feel blessed that my father’s sacrifice was a part of inspiring my sister and I to be the adults that we are today. And on the 50th anniversary of his passing, I’m honored to see his name on this corner, where his story can continue.”

Auxiliary Bishop James Massa of the Diocese of Brooklyn also spoke at the ceremony. He said the newly unveiled street sign is a reminder “that a great New Yorker once lived among us and overcame racial barriers in order to serve, in order to protect the vulnerable and contribute to the common good of our nation.”

Throughout the weekend, 35 members of the Class of 1968 participated in the Thomas More College Oral History Project, which was supported by Fordham faculty and run by a team of students spearheaded by Nutting, a professor emerita of history at North Seattle College.

The project, including audio recordings and transcriptions of the interviews, was published on the Fordham Libraries site last August. It highlights the kind of reminiscences often shared at college reunions—favorite classes, lifelong friendships, and defining moments—from a group of women who saw beyond the boundaries of expectation, both at Fordham and beyond.

‘A Real Blessing’

Nutting, a Washington Heights native who later moved to the Bronx, told stories both hilarious—like the time a professor threw a bologna sandwich out a classroom window—and moving.

“A real blessing occurred when Fordham decided that it would open its gates to women here at Rose Hill,” she said of the college, which opened in 1964 and closed a decade later. “If I had not come here, I would not be the kind of person I am,” she added. “Intellectually, socially, politically, religiously, Fordham transformed me.”

Nutting said that one of the most powerful memories she has of her time at TMC is of taking a Greyhound bus through the American South with Lorraine Archibald, her only African-American classmate.

After working together in Mexico and living with a local family as part of a Fordham program one summer, Nutting and Archibald were forced to take buses home because of a national airline strike. Out of fear for Archibald’s safety, they decided that Nutting would get off the bus alone to get them snacks at a rest stop in Texas.

“I was coming back,” she said, “and all of a sudden I was surrounded by what I call ‘good ol’ boys’ who wanted to know why I was sitting with that … they used the n-word. And I lost my Irish temper in a way a New Yorker can lose a temper.”

Nutting’s response defused a tense situation, but the long bus ride home “profoundly changed me,” she said.

She also recalled taking a course with legendary media critic Marshall McLuhan, who held the Albert Schweitzer Chair in the Humanities at Fordham at the time. “He taught us about the global village and he talked a lot about looking at the rear-view mirror as you go forward. Those two lessons became really important as I moved forward in history, and particularly as I taught history, because you need to have that perspective when you’re heading in a new direction.”

‘She Expected Great Things of Us’

Barbara Hartnett Hall, a Bronx native who discovered TMC when a recruiter came to her high school, also told her story as part of the project. She did not always think of higher education as a realistic possibility, but after receiving scholarships from New York state and from Fordham, she was able to attend.

“I felt like the luckiest person in the world,” she said. “I couldn’t imagine that that world was going to be open to me.”

Now a shareholder at Greenberg Traurig in Fort Lauderdale, where she practices land use and environmental law, Hall recalled being intimidated by the academic options at TMC. She signed up for 18 credits in her first semester before meeting with assistant dean Patricia R. Plante, Ph.D., who encouraged her to drop three credits. “‘You’re in New York City,’” she said Plante told her. “‘You know, this city is an education. You have to take advantage of it.’”

“She was pretty amazing,” Hall said of Plante, who later became the first woman dean of TMC, “because she treated us like she expected great things of us and that we were capable of it.”

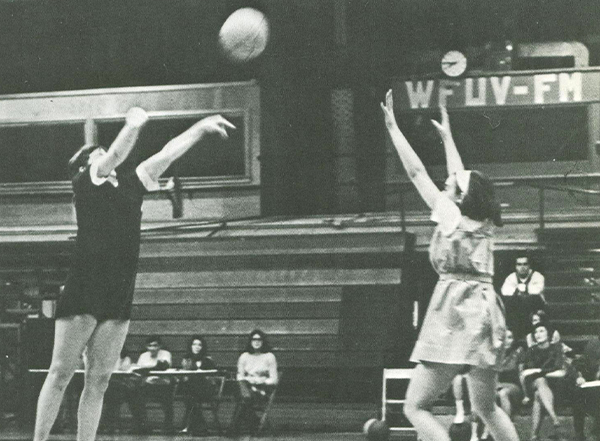

Hall also shared memories of her time as co-founder and captain of the women’s basketball team. The women wore uniforms designed by a teammate’s older brother. “They seemed cool then,” she recalled of the outfits, “but they were funny when you look back.”

In talking about her time at TMC and afterward, Hall recalled walking into many new and unknown situations, including in the workplace. “I think there were a lot of firsts in our generation” she said, “and Thomas More was just one.”

‘My Life Was Suddenly Changing and Expanding’

Like Hall, Marie Farenga Danziger was born and raised in the Bronx, and saw a previously unthought-of opportunity arise with the opening of TMC.

She said that coming back to the Rose Hill campus for Jubilee last year gave her “this instant recall of my very first day at Fordham in September 1964. I remember walking up that path, in particular, focusing on the lovely trees on each side of the path and somehow knowing that my life was suddenly changing and expanding, and I was enormously excited.”

As a junior, she took the transformative step of studying abroad in Paris for the year, an opportunity that had drawn her to Fordham when looking into colleges. Despite having never flown on an airplane before leaving for Paris, Danziger became worldly during her year abroad, traveling throughout Europe and becoming fluent in French.

“It changed the rest of my life,” she said of the experience. “It made me the person I am today.”

Other formative experiences Danziger had at Fordham came from her time as the social chair for the Horizons club, which invited notable speakers to campus. In that role, she brought famous figures like Helen Hayes, Salvador Dalí, and Sidney Lumet to Rose Hill. This kind of cultural exposure made Danziger “feel that there [was]this wider world out there, and maybe, maybe, I had a bit of access to it.”

Danziger, who retired from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government just before the 2018 reunion, was touched to discover that several of her fellow alumnae still remembered her speech as class salutatorian in 1968. The speech, which came on the heels of the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, referenced the movie Zorba the Greek, in which the title character teaches a young man how to dance in the face of sadness and violence.

“Fordham taught us to dance,” she said. “It certainly did that for me.”

Nutting expressed the same sentiment with a different metaphor: “I have told many people in my life that Fordham gave me wings,” she said.

“I want to see you soar,” she told the student interviewers. “In 20 years, I want to find out what you have done with your lives. And one of the things that you’re going to find out as women is that there are going to be some really difficult choices. Make them the best way you can … and you’ll find that you can do that.”

Jubilee 2019 will take place on the Rose Hill campus on May 31 through June 2.

—Adam Kaufman contributed to this story.

]]>Last spring, Jost taught Community Service and Social Action. His students complete 30 hours of service in the Bronx at more than a dozen community-based organizations. Markey, who taught The City and Its Neighborhoods, had her students immerse themselves in the study of a particular Bronx neighborhood. Both will be teaching the courses again next spring.

Both raised outside of New York City, they are now raising families and working in the Bronx. Markey is an investigative reporter who teaches journalism at Lehman College; Jost is director of organizing at Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association, a housing-focused nonprofit in the South Bronx.

The two recently sat down with Fordham News at 188 Bakery Cuchifrito, a Puerto Rican eatery just off the Grand Concourse. As neighbors popped in to buy coffee, crispy chicharrón, tropical fruit drinks, and lottery tickets, Jost and Markey talked redlining and gentrification, as well as art, food, music, and all things Bronx.

TS: When did you feel like you were from the Bronx?

EM: It happened over time. I have a memory of coming back one summer, I must have been picking up a friend or something. I remember driving in on Kingsbridge Road and it being hot and hearing all the music from the street and thinking, “I really miss the Bronx.” In terms of moving here, I knew that I wanted to come to the Bronx because I knew this neighborhood from my time at Fordham and from the newspaper. We were young adults, recently married, settling down. This was the place where we were gonna live permanently now. And then a bunch of other friends moved into our building, other Fordham people who chose the Bronx, who stayed and who were all doing work here. Most of those families are still around. But I think an important transformation—when I stopped thinking of myself as a Fordham person who moved to the Bronx—was really when I had kids. Then you really belong to a neighborhood and you have to make all these moral decisions around schools.

TS: Gregory, what about you? When did you feel that you were from the Bronx?

GJ: I think the real shift comes when you realize that you and everybody around you are actually in something together, that these are all your friends, your neighbors. For me, it was a work in progress, because coming out of a strong service-oriented model I had a lot of issues to come to terms with around power, personally. I had to switch to a framework of not doing anything for people, but doing things with people.

TS: How can Fordham students distinguish their residential role from that of a tourist?

EM: It’s become more and more clear to me that the way we speak about neighborhood change and gentrification, we use the exact same terms as when talking about conquest. Terms like “pioneers of the neighborhoods,” or “settling neighborhoods,” or “I’ve discovered this neighborhood.” I don’t even like to use the word “explore.” I’m a journalist, so one of the students’ first assignments is to do what reporters do. It’s called a “beat note” of a neighborhood. When a reporter takes over a beat, you produce a big document about the geography, where the schools are, where the houses of worship are, who’s leading them, how old they are, etcetera. I’ve been really struggling not to use the word “guidebook.” I don’t want students to be part of tourism, which is really impossible to remove from a colonial history. A better way to say it would be “asset inventory,” because I want to get across this idea that neighborhoods have strengths. I think one difficulty is that students arrive in the Bronx and only see the problems. Sometimes that comes out of a decent, generous do-gooder instinct, but it doesn’t lead to good things. This neighborhood has tremendous strengths; it’s not a problem that you need to solve.

TS: As someone who lives and works in the Bronx, does it bother you when you meet students don’t know much about the borough and its past?

EM: I mean, one wouldn’t know unless you took a class, right? I didn’t know post-modern literature until I took a post-modern literature class. But I have students who are juniors and seniors who don’t know the Bronx.

TS: How do you teach that responsibly?

GJ: We’re really talking about power, and wealth is a piece of that. Students need to understand why there’s massive wealth disparity—opportunity disparities that exist even between students in the classroom, but then definitely between Fordham students and people who live in the neighborhoods surrounding campus. And that’s not just the history of the Bronx, that’s a history of the whole country.

TS: If that’s the case, how do students make the connection?

GJ: Most of the kids at Fordham, their parents used to live in the city, or their grandparents. You can see your family story in this natural story by asking, “Where did we live in the city? Why did we move out? How did we benefit from moving out? How were we able to build wealth through that?” Now I can come back into the neighborhood, and I’m in a position now to do service or just go explore—in a way that there is a power dynamic. If you’re not aware of that different power disparity when you’re going out into neighborhoods, you’re not going out in a responsible manner.

TS: What’s the difference between service learning and social justice?

EM: For me, when I was a high school kid at a diocesan Catholic school in Massachusetts, we did lots of community service. It was better than not doing community service, but it’s not as good as doing social justice work. When I came to Urban Plunge, we got this history lecture about the fires, the ’70s, disinvestment, and suburbanization. A lot of institutions pulled up stakes and left, but what Fordham did instead helped to found Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, which helped the neighborhood, but from within. We were invited to be, and this is so cool, to be a part of history.

GJ: When I’m on a panel and we’re talking about gentrification, this is exactly what I’m talking about. If you’re doing service without acknowledging the power disparity and then doing something to rectify that, then we’re not actually solving any problems. We’re not dealing with the underlying issue. You want to be looking at the structures. There’s a structural injustice, there’s systematic injustice, and there’s a perfect corollary to that in Catholic social teaching: that’s a structural sin. It’s a good thing to go do service for a couple hours in the soup kitchen, but we need to dig deeper into what we can do to disrupt the systems that keep people relying on soup kitchens in the first place, and create a society where we don’t have that inequity.

TS: Could some of these disruptions simply be going out to a restaurant or concert or learning about the culture by simply participating in the culture?

GJ: The best Urban Plunge experience I ever witnessed was everyone walking up to Poe Park. It happened to be the day of one of those free live concerts and they got the mobile stage, and it was salsa music, and everyone was out dancing. There was no power dynamic present.

I mean, if you want to talk about the things that came out of Bronx, it’s music and food. In good times and bad times, from Latin jazz and doo-wop to hip-hop. All these different moments, there’s a ton of creation happening, something that people value. And so, this is where it comes to a value question and who has value to contribute.

TS: The Bronx is back and it is extremely attractive, suddenly, to investors. What now?

EM: All these good things are things that the people who survived fought for, and those things didn’t happen because white people from the Village wanted them. It is because people who survived organized and fought and demanded it. People fought tooth and nail for 20 years to reclaim their river and to reclaim their parks. If they don’t get to live there anymore, which is a hundred percent happening, it’s so awful because the only reason it’s nice is because the people who were there made it nice and fought for it to be nice, and fought for it against tremendous resistance.

TS: Sounds like redlining in reverse.

GJ: It is so important to talk about like race and place, the reason neighborhoods were redlined was because of “infiltration” of people of color.

EM: Which is the term that was used on government paperwork.

GJ: There was a systematic devaluing of land based on the presence of people of color. And the flip side is that now when you have a piece of land that is attractive to white people there’s a system of mass displacement that’s generally pushing people of color around. You could say the Bronx is the last stand in New York City.

Last fall, Playbill listed Fordham among the colleges most represented on Broadway, so it’s no surprise to find three alumni and one Fordham Theatre faculty member among this year’s Tony Award nominees.

Fordham Theatre alumna Julie White, PCS ’09, is up for best featured actress in a play for her turn in Gary: A Sequel to Titus Andronicus. Written by Taylor Mac, Gary is an imagined sequel to Shakespeare’s violent revenge drama. It’s set amid the decline of the Roman Empire and tells the story of the minor characters left with the macabre cleanup work following the gruesome events of Shakespeare’s original.

In her review for Vulture, Sara Holdren praised the “combined zaniness and pathos of [White’s] marvelously feverish performance” as Carol, a midwife who is merely mentioned in Shakespeare’s play, and added that it is “all but impossible to imagine Gary without [her] brilliantly kooky antics.”

White previously won the Tony for best actress in a play in 2007 for The Little Dog Laughed, and she was also nominated for best featured actress in a play in 2015 for Airline Highway.

Meanwhile, Ephraim Sykes, FCLC ’10, has been nominated for best featured actor in a musical for his role as David Ruffin in Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of the Temptations. New York Times critic Ben Brantley noted Sykes’ “spectacular scissor splits” and “smoking hot” performance as the music legend who sang lead vocals on Temptations hits like “My Girl” and “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg,” but who was as personally troubled as he was talented.

“This is the most monstrous role I’ve ever had to take on,” Sykes told Broadway.com. “The award [for me] is when I walk out of the stage door, and I meet somebody that says, ‘What you did really connected to me.’”

A graduate of the Ailey/Fordham B.F.A. in dance program, Sykes has previously been nominated for three Astaire Awards for his roles in Broadway productions, including Hamilton. He has also toured with the Ailey II dance company, and in 2016, he played Seaweed J. Stubbs in NBC’s televised live production of Hairspray!

Tony Award winner Clint Ramos, who joined Fordham Theatre last fall as head of the design and production track, has been nominated for best costume design for his work on the play Torch Song. He won the Tony in that category in 2016 for his work on the play Eclipsed.

Rounding out this year’s list of Fordham nominees is producer John Johnson, FCLC ’02, who got his start on Broadway as an intern for Joey Parnes Productions during his junior year at Fordham Theatre. He has a total of seven Tonys to his credit (among Fordham alumni, that’s second only to his mentor, Elizabeth McCann, LAW ’66, a nine-time Tony Award-winning producer).

This year, Johnson has been nominated twice, as an executive producer of best play nominee Gary and of The Waverly Gallery, which is up for best play revival.

Six additional members of the Fordham family are part of productions that have been nominated for 2019 Tony Awards:

- Siena Zoë Allen, FCLC ’15, associate costume designer, What the Constitution Means to Me

- Kaleigh Bernier, FCLC ’16, assistant stage manager, Be More Chill

- Jessie Bonaventure, FCLC ’15, assistant scenic designer, What the Constitution Means to Me and Hadestown

- Drew King, FCLC ’09, ensemble, Tootsie

- Fordham Theatre student Wayne Mackins, ensemble, The Prom

- Michael Potts, former Denzel Washington Endowed Chair in Theatre at Fordham, Mr. Hawkins, The Prom

The 73rd Annual Tony Awards ceremony will be held on Sunday, June 9, at Radio City Music Hall in New York City.

Dinner and a Show: Fordham’s alumni office hosts theater outings as part of its cultural events series. On May 9, a group of alumni and guests saw Tootsie and heard from Fordham grad and ensemble member Drew King, FCLC ’09, in a special talkback session after the show. Plans are underway for an October outing to see Ain’t Too Proud featuring Tony-nominee Ephraim Sykes, FCLC ’10. Tickets will be available soon via the alumni events calendar.

]]>Then, in sophomore year, one of his professors—Mark Naison, Ph.D.—learned of his worries and called a Fordham administrator in search of funding help. And that’s how Purnell became one of the scores of students who benefit every year from the UPS Endowed Fund, Fordham’s largest donor-supported scholarship fund and one of the oldest scholarship funds at the University.

Money was a real concern for Purnell and his family; his father was a New York City transit worker and his mother worked as a secretary at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The UPS funding award not only eased their financial worries but also gave Purnell new confidence to apply for external funding for his undergraduate and, later, his graduate studies.

“It just really motivated me,” said Purnell, a 2000 graduate of Fordham College at Rose Hill.

“I can remember just feeling very supported by the school, very encouraged to continue to pursue academics, and to do the best that I could in the majors that I had begun to gravitate towards.

“It was an indication that the studies that I was doing in the humanities were valued,” Purnell said. He later earned a doctorate in history at New York University, taught at Fordham, and worked as co-research director on Fordham’s Bronx African American History Project. Today he is the Geoffrey Canada Associate Professor of Africana Studies and History at Bowdoin College.

Purnell is one of hundreds of students for whom the UPS Endowed Fund has made a pivotal difference since it was established five decades ago. Without it, many would not have been able to attend Fordham at all.

Origins of an Endowment

The endowment emerged out of relationships among UPS officials and Leo P. McLaughlin, S.J., president of Fordham from 1965 to 1969, said Arthur McEwen, FCRH ’55, a retired vice president of human resources at UPS.

Father McLaughlin had gone to grammar school and high school with Walter Hooke, a civil rights and labor activist who was vice president of personnel at UPS, said McEwen, who reported to Hooke at the time. The company president, James McLaughlin, had gone to a Jesuit high school in Chicago, and his son was a Jesuit scholastic teaching at Fordham Prep, McEwen said.

Father McLaughlin invited the two UPS officials to dinner, where the talk turned to the undergraduate college that would soon open at Fordham’s new Lincoln Center campus, and how the University could foster more racial diversity among its students.

When the college opened in 1968, the first entering class included 55 minority students who benefited from a new scholarship funded by UPS’s philanthropic arm, the 1907 Foundation (later renamed the UPS Foundation), McEwen said.

Supplemented with further gifts from the foundation, the UPS Endowed Fund has grown to $18 million and currently supports 154 students at both the Rose Hill and Lincoln Center campuses.

In decades past, the fund has had other uses: It helped teachers in the South Bronx attend Fordham’s Graduate School of Education, for instance. It also supported an internship program for Graduate School of Social Service students at the South Bronx’s Highbridge Community Life Center.

Creating Opportunity for Students

Today, the fund provides the UPS Scholarship to a diversity of students who would not otherwise have been able to attend Fordham. And it often provides financial flexibility that transforms students’ experiences at the University; past scholarship recipient José Haro, FCRH ’00, was able to study in Mexico for a year, and also did well academically “because I actually had time to study” rather than work for money, he said. He estimated that the scholarship from UPS covered about 20 percent of his costs.

When he got to graduate school, he felt well prepared. “I can’t put a value on the education I got from Fordham,” said Haro, an assistant professor of philosophy at the Borough of Manhattan Community College. He earned master’s degrees at New York University and at the University of South Florida, where he also earned his doctorate.

For Adrienne Boykin, GABELLI ’09, the scholarship funding from UPS came at a critical moment in sophomore year. A first-generation college student, she had transferred to Fordham from a community college, drawn by the top-flight accounting program and the Jesuit education. But finances were always a big concern, and she was having doubts that she could afford to stay.

“I thought all the pieces were falling apart,” she said. “But when I was able to get this scholarship, I just felt such a sense of relief and joy.”

Upon graduating, she went to work for accounting giant PwC, or PricewaterhouseCoopers, having taken advantage of its recruitment relationship with Fordham. “It was a very good job coming out of college,” she said. “Being at another school, I’m not sure that I would have been able to have that specific access” to employment opportunities at the firm, said Boykin, who is now the director of finance and administration at America Needs You, a nonprofit that provides mentoring and career development support to first-generation college students.

Many current recipients describe the scholarship as an important piece in the financial aid puzzle that brought a Fordham education within view. Mia Kroeger, a sophomore from Roswell, Georgia, was considering many colleges until she visited the Rose Hill campus. She was awestruck, “and when I met the people, I realized this was the perfect place for me,” she said.

The UPS Scholarship brought Fordham within the realm of possibility. “It was a big relief,” she said. Being able to choose Fordham “was really, really exciting.”

]]>That was the year that Kawa, GABELLI ’65, moved into Queen’s Court on the Rose Hill campus. There, he met Patrick Rogers, Joseph Furfaro, Frank Ferro, and Quentin Lauer II, all of whom would graduate with him four years later from the Gabelli School of Business.

Fifty-eight years later, Kawa is paving the way for future students to follow in their footsteps. After making a $1.5 million gift in 2014 to support the information and media technology center at Hughes Hall, the Rose Hill home to the Gabelli School, Kawa funded a scholarship for Gabelli School undergraduates with a $150,000 gift. At a 2015 ceremony during Kawa’s 50th anniversary Jubilee in which the center was named for him, he beseeched his classmates to follow his example.

“I said, ‘I want to do one every year, for as long as God lets me live.’ And Father McShane said, I’m going to say a prayer right now that you live a very long life, Jack,’” he recalled, laughing.

Kawa has lived up to his vow; since the initial scholarship he created, he has funded four more for Gabelli School students. He’s added a twist though: These scholarships bear both his name and those of Rogers, Furfaro, Ferro, and Lauer.

In addition, the Kawa/Furfaro scholarship is in memory of Joseph Sutera, the Kawa/Ferro scholarship is in memory of Michael Collins, and the Kawa/Lauer scholarship is in memory of Rich Kelly.

In creating the scholarships, Kawa, a resident of Knoxville, Tennessee, who made his career as a stock analyst specializing in transportation companies, said he wanted to celebrate the lifelong friendships he witnessed and inspire others to honor their friends in the same way.

“Although I like to see my name in print, if you see your name five to 10 times in a row for a scholarship, it’s a little much,” he said. “I thought, why not highlight some of the students who made Fordham what it is today?”

Donna Rapaccioli, Ph.D., dean of the Gabelli School, said gifts like Kawa’s are at the heart of the school’s drive to be a center for “business with purpose,” particularly as it prepares to celebrate its centennial anniversary in 2020 and as the close of University’s Faith & Hope | The Campaign for Financial Aid draws near.

“Scholarships provide an essential opportunity to create diversity of thought in our classroom,” she said. “Jack’s generosity is unique in that it honors others, and it’s also significant that he’s targeted it toward scholarships, which are essential for us to attract and retain a talented student body.”

Although he was close to Rogers and they stayed friends after graduation, Kawa said he didn’t have a lot of time for socializing on campus. He worked during his junior year at the library, and in his senior year he manned gas pumps along the Major Deegan Expressway from 8 p.m. to midnight.

“That took me out of a lot of campus activities. If I look back at it again, I wouldn’t have done that. I should have stayed on campus, and participated more. But that’s the past,” he said.

Touched and Honored

Rogers, who roomed with Kawa his first year and a half at Fordham and still talks over the phone with him daily, said it was poignant to be named in a scholarship as he himself benefited from one.

“I don’t really care about the immortalization; I’m not going to be around to see it, and that’s OK. I just think that that this is something other people might have never thought of, and they might think, ‘That’s something I could do,’” he said.

It’s also fitting that Ferro and Collins are named in the scholarships, Rogers said, as he vividly recalls he and Kawa facing off against them in bridge games over the years.

“I still play today. My doctor tells me it’s a way to keep my mind sharp. One of my fondest memories is me and Jack together, playing bridge,” Rogers said.

For Ferro, Kawa’s idea was a surprise. Although he remembers the bridge games and playing with Kawa on a club football team that nearly beat the upper-class team in a game on Edwards Parade their first year, he said Kawa had drifted away from the campus social scene by senior year. He’d heard Kawa was funding scholarships, but didn’t give it much thought.

“Then out of the blue, I get a call from Jack. He led off with, ‘You don’t have to do anything. I’m going to do everything. I’m going to finance this totally myself.’”

When Kawa said he wanted to honor Collins, Ferro said he was extremely touched. Ferro and Collins were roommates for four years, and Collins would have been the best man in his wedding had he not been drafted for service in the Vietnam War. He died recently of brain cancer. “He still appears in my dreams regularly,” Ferro said.

“My senior year, the apartment we shared on 193rd Street and Webster Ave was a social center of the university. We threw parties that started at 6:30 and ended at 6:30. It was just astonishing, and Collins was a big part of that. So, it was a good gesture on Jack’s part,” he said.

‘Connections, Connections, Connections’

Furfaro was closer to Kawa, and had him in his wedding party in 1965. He too was touched when Kawa said he wanted to dedicate a scholarship to Joseph Sutera, who’d been Furfaro’s best man in his wedding. Sutera died suddenly on a business trip when he was just 50.

“I had lunch with Joe’s widow, and she was just so touched that Joe’s classmates would remember him. Jack touched the hearts of the whole Sutera family by making this in memory of Joe,” he said. “Joe’s daughter is my goddaughter. So there all of these connections, connections, connections. I think it just brings more of the Fordham family into the picture.”

Furfaro recalled that at the 2015 Jubilee, Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, told them that their story is “the Fordham story.” He also made a small contribution to the scholarship, to show his support.

“What Jack is doing is enhancing the Fordham story amongst all of his classmates,” Furfaro said.

Like Ferro, Lauer wasn’t the closest to Kawa. But he noted that back then, commuter students outnumbered residential students, so there was a natural bond between those who lived on campus. Rich Kelly, who he lived with for four years and who is honored on the scholarship with Lauer’s name, was from Jamaica, and when Lauer and his wife honeymooned there, Rich and his family arranged everything for their visit, he said.

Although Kawa, who retired as senior vice president of Dean Witter Reynolds in 1997, said he regrets not spending more time on campus, he said the education he received set him on a path to an extremely successful career.

“I was a bear with numbers. What I learned in accounting was invaluable for what I did on Wall Street,” he said.

Jamie Wang, a junior majoring in accounting, is the first recipient of the first scholarship that Kawa created. In a letter she wrote thanking Kawa, Wang, who transferred from Baruch College in 2017, noted that her mother had pressed her to consider transferring to a public college rather than Fordham.

“This scholarship, as well as my hard work I’ve put in since transferring, has convinced her to allow me to continue my education in my dream school and work towards a degree in my desired career,” she said.

“I want to thank you for your generous contribution. It has made it possible for me to continue my education here at Fordham.”

Stories like Wang’s are what inspire Kawa to give.

“Fordham is number one on my hit parade, and I like the scholarship idea, because you’re giving money to kids who couldn’t theoretically go without any financial help. In addition, the scholarships that can be set up to honor classmates and their friendships will last forever.”

]]>With the Nets having capped off a successful regular season that led to a first-round playoff series against the Philadelphia 76ers, Love spoke with FORDHAM magazine about her game night responsibilities, her passions and pursuits, and what was special about the education she received at Fordham.

How did you first come into the Nets hosting gig?

I fell in love with on-camera work, so I started taking hosting classes. When I finished, I emailed the class reel to everyone in my contacts, most of whom I didn’t even know, letting them know I was open for hosting business. Next thing I knew, I got an email offer to host the Brooklyn Nets!

What does a game night look like for you? Can you walk us through the process and timing from when you get to the arena to when you leave?

I get to Barclays Center two hours prior to tip-off, and we have an entertainment meeting, which includes going over the “run of show” for that evening’s game. Afterwards, I get ready for the game and review my lines. My first hit happens around 7 p.m. if it’s an evening game. Then, I welcome everyone to the game and introduce the teams around 7:10 p.m. From then on, I am on pretty much every timeout during the game. I’m on court and in the stands doing fan interactions, on-court games, interviews, and marketing plugs. I leave at the end of the game.

With the team having such a successful season and now being in the playoffs, have you noticed a change in the atmosphere at Barclays?

Leading up to [and during the] playoffs, the energy is always taken up another level. Brooklyn has something so special about it, as a borough, community, and team, and that energy always spills into the arena. As we got closer to the postseason, you could feel the grit and energy of our team taking it to the next level.

You are also a Peloton instructor, model, and the founder and CEO of Love Squad. How do you balance all that in your day-to-day? And what are your plans for the future in these different areas?

Well, I love all the things I do, so they fuel me. The thing that all of these platforms have in common is the opportunity to affect my community positively by utilizing live, on-camera interaction. I plan to continue to create content that will inspire communities across the world.

I also have big hopes for my company. Love Squad is a big part of who I am and reflects what I stand for, which is diversity, empowerment, and love. I founded it on my own a few years ago and want to continue to grow it into the platform I know it can be. Love Squad creates a space that champions inclusivity and diversity, and deconstructs the disparity in who is able to receive information that could change people’s personal and professional lives. If you have the network, you learn and you’re exposed to more, which offers a chance at a better opportunity in life. So the more we grow, the more people we can help. That’s what my main focus is right now.

You earned your B.F.A. from Fordham through its partnership with the Ailey School. How has your training there impacted your career?

I think it gave me discipline. It afforded me an opportunity to establish a personal metric for success safely, within the construct of school, while experiencing a big city. It also encouraged me to immerse myself in elements that allowed me to be creative, and to use that as a conduit for production beyond basic utility.

What first attracted you to the program at Fordham?

I loved that it was in New York City, specifically right in midtown. I also felt like it was the perfect hybrid of arts, culture, and academics while offering independence, which were very important characteristics.

What did you get out of the combination of a high-level dance program and a Jesuit core curriculum?

I was able to find myself. I was always dancing (pun intended) between the arts and religion. Fordham provided the foundation and opportunity to explore both simultaneously, and it opened my mind to the fact that they were not mutually exclusive. There was room for me to merge both, and it ultimately molded me into the woman I am today.

Luckily for fans, hundreds of episodes from The Big Broadcast’s archive are now available to stream on Fordham’s Digital Collections page, thanks to a generous donor and a collaborative effort between WFUV and the University Library.

“It’s a wonderful tribute to Rich and his knowledge and infectious passion for this timeless music,” says Chuck Singleton, general manager of WFUV. We’re grateful to our anonymous donor for his support, and to the Fordham Library team for providing a new home for these wonderful sounds to be enjoyed for generations to come.”

Conaty started The Big Broadcast in 1973, as an undergraduate at Fordham, and over the course of 43 years—almost all of them at WFUV—he attracted a dedicated fan base that listened as much for his encyclopedic knowledge and humor as for the pre-World War II playlists featuring the likes of Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Bessie Smith, and Benny Goodman. He would play from his expansive collection of often-rare records, giving listeners biographical details of the composers, singers, and musicians they heard.

When he stepped away from the program in September 2016, dealing with the lymphoma that would take his life months later, Conaty had hosted more than 2,200 episodes of The Big Broadcast and had gotten the chance to meet some of his musical idols, including the Boswell Sisters, Bing Crosby and the Mills Brothers, Mitchell Parish, and Calloway.

Michael Considine, director of Fordham’s Electronic Information Center, and his staff worked through technical and legal issues on the way to getting the show’s broadcasts digitized. To comply with copyright law, listeners can drop in on a stream that plays episodes continuously, one after another, allowing users to start and stop the stream but not select specific shows or songs.

While fans may miss the voice of Conaty live on Sunday nights, the new digital archive gives listeners a chance to hear his signature “Aloha” anytime they like.

“We’ve heard from perhaps one hundred fans of the show, and they are over the moon to be able to hear those shows again,” says Singleton. “Rich’s sudden passing was very hard on his fans, including all of us at the station. There is a lot of gratitude to Rich’s alma mater for making [this archive]possible.”

You can listen to the Big Broadcast stream at library.fordham.edu/juke7.html.

]]>Here are some recent graduates who have experienced just that.

Kamrun Nesa, FCLC ’16

Major: English

Minor: Political Science

Course: Publishing: Theory and Practice

The aim of this course is to develop a clear understanding of the publishing industry. Students examine a wide range of genres and hear from speakers in the field.

Current Jobs: Associate Publicist at Grand Central Publishing; Freelance Writer for NPR, USA Today, and Others

“This course was my first foray into book publishing, and it helped me secure my first book-related internship. Thanks to these internships and a wealth of experience in my classes and at The Observer, my first job right after graduation ended up being in publicity at a publishing house.”

Peter Vergara, FCRH ’18

Majors: Art History and Philosophy

Minors: Latin American and Latino Studies and Political Science

Course: Modern Latin American Art

This course looks at two great shaping forces of modern Latin American art: nationalism, which called on visual art to create a national identity and to reflect it; and modernism, an aesthetic movement that insisted on artistic autonomy.

Current Job: Day Sale Administrator for Impressionist and Modern Art at Sotheby’s

“In studying art by Latino artists post-1920, I was able to see dialogue and interaction between Latin America and the United States, along with how artists deal with the heritage of colonial Spain. This fascinated me, and it helped shape where I want to go with my career.”

Elaina Koukoulas, GABELLI ’17

Major: Public Accounting

Course: Contemporary Issues in Financial Forensics

This course focuses on methods of fraud investigation, detection, and prevention, including the professional responsibilities of the CPA.

Current Job: Financial Investigator at the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office

“I decided to enroll in this class after my forensic accounting internship at the Manhattan DA’s office. The class not only explained the basics of forensic accounting but also dove into extensive detail and explored its relevance to the business world today. It increased my passion for forensic accounting and served as a confirmation that I had finally found what I wanted to pursue after college.”

Luis Benitez, FCRH ’19

Major: Computer Science

Minors: Mathematics and Cybersecurity

Course: Philosophy of Human Nature

A philosophical reflection on the central metaphysical and epistemological questions surrounding human nature.

Current Job: Technology Associate at Wellington Management

“My liberal arts classes taught me to think and have even influenced my approach to programming and coding. In this philosophy class in particular I saw a lot of connections to computer science. I learned to express my train of thought and also to separate feelings from observations, to think of things objectively—like you do in computer programming. It’s all logic.”

Nicholas Hardiman, GABELLI ’17

Major: Business Administration

Concentrations: Finance and Marketing

Minor: Information Science

Course: Consumer Behavior

This class focuses on the role of psychological factors in the behavior of humans as consumers.

Current Job: Account Manager at Google

“My Consumer Behavior course taught me to pay attention to the compounding factors that lead people to make the decisions that they do. Focusing on figuring out consumer behavior patterns has helped shape my career in digital advertising. As data-driven marketing continues to evolve, I hope to be on the forefront of helping businesses develop new advertising strategies.”

Emily Rubino, FCLC ’17

Majors: Humanitarian Studies and Sociology

Course: Gender, Crime, and Justice

This course describes, explains, and challenges the treatment of victims, offenders, and workers in the criminal justice system. In the process, students examine and critique issues of criminal law, race, class, and sexuality.

Current Job: Director of Policy and Outreach at Peace Action New York State

“This is one of the courses that had a big impact on the ways I think about social justice and how we function as a society. My study abroad in the U.K., Nepal, Chile, and Jordan further complicated my thinking on these issues, as everywhere I traveled it was clear that people had been impacted by U.S. foreign policy. This was extremely helpful since my job requires knowledge of both international relations and domestic social justice issues.”

Chloe Potsklan, GABELLI ’17

Major: Information Systems

Minor: Spanish

Course: Cybersecurity in Business

This class explores the value cybersecurity and computer science professionals bring to business.

Current Job: Cyber Risk Consultant at Deloitte

“My cybersecurity class helped me learn more about today’s cyber landscape in the business world. I took the class just after accepting my full-time offer with Deloitte after my summer internship there. It served as a continuation of what I learned during that internship and prepared me for my current work environment.”

Nathan Miranda, FCLC ’16

Majors: Computer Science and Music

Minor: Mathematics

Course: Speech and Rhetoric

This course examines rhetorical theories and strategies of thinkers ranging from Aristotle to Stephen Colbert, and explores how to listen, ask questions, persuade and be persuaded, and suggest new directions of inquiry.

Current Jobs: Software Engineer at Compass; Front-End Engineering Instructor at the Flatiron School; Piano Instructor

“This class was key in transforming some of my introverted tendencies into extroverted confidence. I gained awareness that has helped me both in my career and in expanding my relationship circles. The environment of the class was typical of Fordham—open to all ideas with complete ownership of presenting topics in a manner that would engage your peers.”

Suliman Al Aujan, GABELLI ’15

Major: Applied Accounting and Finance

Course: Special Topic: Alternative Investing

This course covers the evolution and outlook for a range of alternative investments. Students analyze research and case studies, and hear from guest speakers.

Current Job: Mandates Portfolio Manager for the Global Real Estate Team at Credit Suisse Asset Management London

“The Gabelli School applies both theoretical and practical learning experiences. This capstone course emphasized application-based learning and drew upon real-world problems, like how financial institutions can support developing access to fresh water sources in Africa. Our professors treated us like analysts and urged us to solve these problems, an analytical experience I draw upon in my current work.”

Natalie Wodniak, FCRH ’18

Majors: Environmental Studies and Humanitarian Studies

Minor: Biological Sciences

Course: International Humanitarian Action and New York City

This course examines international responses to various types of humanitarian crises.

Current Jobs: Field Organizer at NextGen America; Master in Public Health Candidate in Global Health Epidemiology and Disease Control at George Washington University

“This class greatly impacted my career path. I was able to expand my knowledge about global crises and learn about ways to get involved in the humanitarian community. Humanitarian studies courses like this one, along with my Intro to Virology course, helped me decide to enter the field of global health.”

Do you have a classes to careers story of your own? Email us at [email protected].

]]>