That’s the question recently addressed by a Fordham student’s faculty-mentored research project. While scholars have long suspected that people with disabilities tend to get left behind in schooling, in employment, and in other sectors of life, the research by Emily Lewis, FCRH ’22, found that there is even more of this inequality in richer countries. And it suggests that policies may be needed to ensure growth and development benefit all people in a society.

Disability “tends to be ignored when we speak about inequalities,” said economics professor Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., co-director of the disability studies minor and founding director of Fordham’s Research Consortium on Disability. “And yet, disability is key when it comes to understanding people’s livelihoods, people’s standard of living.”

Mitra was the mentor for Lewis, an economics and philosophy major who spent last summer analyzing international disability data with support from a summer research grant. Such funding for student-faculty research is a priority of the University’s current fundraising campaign, Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student.

Lewis, Mitra, and economics doctoral candidate Jaclyn Yap are co-authors of the resulting research paper, Do Disability Inequalities Grow with Development? Evidence from 40 Countries, published April 25 in the academic journal Sustainability. The research sprouted from another project led by Mitra that highlights disability inequalities worldwide.

The Disability Data Initiative

Since 2006, more than 180 countries have ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, an agreement to treat them not as objects of charity and medical treatment but rather as contributing members of society.

To support this goal and help policymakers move forward, Mitra spearheaded the Disability Data Initiative, a report on 180 nations’ census and survey findings regarding people with disabilities from 2009 to 2018. She led a team of graduate and undergraduate students, including Lewis.

Presented at a UN conference last June, the report showed that about one-quarter of nations didn’t ask about disability in their national surveys. In those that did, the data showed major gaps in the areas of education, health, employment, and standard of living between people with disabilities and those without them.

The database opened the possibility of doing an extensive study across countries to see if these gaps increased with development—something that had been long hypothesized but not tested on a large scale.

Eager to explore this question, Lewis made it her summer project. Her interest in the disability gap had been sparked during one of Mitra’s classes, at a time when she was looking for a way to get involved in undergraduate research.

“Seeing examples of how different researchers are approaching these questions was really interesting, and got me excited about how I could design this project for myself,” she said.

It was a big project—and a summer research grant gave her the means to spend the required time on it.

Help from a Fordham Benefactor

This and other grants to students were made possible by an alumni benefactor who has long funded undergraduate research—Boniface “Buzz” Zaino, FCRH ’65, whose long career in the investment world exposed him to the joys of researching and learning about new industries. “Once I got into it, it just opened the world, because you do get to explore and focus on areas that become very interesting,” he said.

He has funded students’ research for years, energized by the students’ enthusiasm for their projects, by what their projects have taught him about the world, and by the benefits to the student researchers themselves.

The research process, with its wide reading and focused inquiries, gives students a base for developing their interests and learning about new things over the long term, he said. “The University provides a student with the opportunity to develop a research process, and that’s got to be very helpful for them going forward, no matter what they do in life,” he said.

The Disability and Development Gap

Lewis met weekly with Mitra over the summer to design and carry out the project, examining 40 countries that have comparable data on peoples’ self-reported difficulties with seeing, hearing, walking, cognition, self-care, and communication.

Working on the Disability Data Initiative, they had already gotten glimpses of a wider disability gap in wealthier countries.

For instance, in low-income nation of Cambodia, 75% of adults with any kind of difficulty caused by disability were employed, just shy of the 79% for those without disability. But in economically booming Mauritius, an island nation in the Indian Ocean, the gulf is far wider, with just 15% employment for those with any difficulty, compared to 56% for those without.

To see if such disparities represented a trend, Lewis crunched a big data set including lots of variables—levels of disability, gender, age, and urban versus rural location, as well as a nation’s place on Human Development Index, or HDI, a UN indicator of nations’ wealth and overall development.

She found that for many standard-of-living indicators, like adequate housing and access to electricity, there was little difference in the disability gap between richer and poorer countries.

But the story was different in three areas: education levels, employment rate, and a multidimensional measure of poverty. Gaps in all three increased as countries’ HDI increased. The results held up when Lewis looked at the data a few different ways, such as focusing on different development measures or population subgroups.

The results, the co-authors wrote, “suggest that as a country develops, policies, specifically in relation to education and employment, need to be implemented to narrow and, eventually, close the gaps between persons with and without disabilities.”

The research shows that while disparities may be greater in wealthier nations, disability inequalities aren’t just a problem in rich countries with older populations, Mitra said. Low-income countries have them too, even if they’re less pronounced.

“Even when almost everyone is poor, well, people with disabilities seem to be even poorer,” she said.

Lewis found it exciting to be involved in the research process and see it through from start to finish—figuring out the approach, changing direction as needed, and working independently. “[It’s] something I consider myself really lucky to have been involved in,” said Lewis, who was planning to work as a project assistant at a New York law firm after graduation to explore her interest in law school.

Mitra said that undergraduate research not only teaches students valuable skills but also gives them an inside look at how knowledge is produced, as well as all the caveats and limitations that come with it—an awareness that will serve them well in whatever field they pursue.

The University’s research grant program for undergraduates is “a unique opportunity for students, but also for as faculty,” Mitra said. “So I hope it does continue to attract the generosity of donors.”

To inquire about giving in support of student-faculty research or another area of the University, please contact Michael Boyd, senior associate vice president for development and university relations, at 212-636-6525 or [email protected]. Learn more about Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, our campaign to reinvest in every aspect of the Fordham student experience.

]]>These are some of the key findings from a new report and database called “The Disability Data Initiative,” released in June at the United Nations’ 14th Conference of the States Parties to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

The project was spearheaded by Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., professor of economics, co-director of the disability studies minor, and founding director of the Research Consortium on Disability, together with a team of seven undergraduate and graduate students. The initiative was supported by Fordham University, Wellspring Philanthropic Fund, and the World Bank’s Trust Fund for Statistical Capacity Building.

The Disability Data Initiative is one of the first of its kind to review and analyze comparable data on disability and inequalities across countries, Mitra said.

The idea for the project stemmed from the fact that more than 180 countries ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities since 2006, but there has been scattered and incomplete data around those with disabilities, which “prevents the development of appropriate and effective disability-inclusive policy,” according to the report.

Lack of Disability Data

Mitra and her team of students reviewed census and survey data from 2009 to 2018 for 180 countries across the world. They found that disability-related questions were missing from 24% of countries.

“It was quite shocking to see that one in four countries do not have disability questions of any kind in their censuses or national surveys,” Mitra said. “In many countries, people with disabilities continue to be invisible. We have no way of figuring out how they are doing from national statistics.”

If people with disabilities aren’t accounted for, their needs are easier to ignore, Mitra said.

“If they’re not captured, they definitely get less attention … and it’s going to be very hard for them to argue that their situation needs improvement,” Mitra said. “Policymakers can say, ‘well, they’re such a small minority, we have other groups to worry about.’”

Their analysis found that people with disabilities are a sizable group as people in “more than one in four households have a functional difficulty,” such as difficulty seeing or walking, Mitra said.

The main question related to disabilities that the team found on many censuses and surveys was “Do you have a disability?” which doesn’t allow for clear and comparable data, according to Sophia Pirozzi, FCRH ’21, who was an undergraduate student on the initiative and was responsible for collecting data from more than 1,000 surveys in 180 countries.

“Disability itself is a concept that only recently has been embraced as a socio-political [notion], as opposed to a medical deficit,” Pirozzi said. “So if we’re looking at international comparisons, a lot of the time the way the disability is defined varies greatly.”

Mitra said there is often stigma attached to the question, so people don’t always answer honestly.

“They may only think of very severe situations to qualify under the word disability,” she said. “If disability in general is stigmatized in society, they think that, ‘well, perhaps I do have a disability, but I don’t feel comfortable answering yes.’ It doesn’t produce useful data—it produces very small prevalence rates, and only captures the most extreme disabilities.”

Disparities for People with Disabilities

The team closely analyzed data from 41 countries who had comparable questions, usually based on questions from the Washington Group Short Set (WGSS) that have become the “gold standard” of surveying people about their level of disability. The questions cover topics such as mobility, seeing, hearing, communication, and cognition, and allow people to respond with a range of answers. Mitra and her team said that they would like the WGSS to be adopted and used by more countries.

“A lot of these were where we were able to compare persons who said, ‘I have no difficulty,’ or ‘I have a lot of difficulty,’ or a little bit. And that’s really useful information for us,” said Pirozzi, an English major and disabilities studies and sociology minor, who is currently interning at the United Nations in the department of economic and social affairs.

Mitra noted that this was “one of the first international efforts to document functional difficulty prevalence and education, work, health, standard of living and multidimensional poverty indicators for adults with and without functional difficulties.”

The analysis found that there was “a disability gap” in terms of quality of life between people with disabilities and those without This was true across countries in areas including educational attainment, literacy, food insecurity, and health expenditures.

For example, in Indonesia, 93% of respondents with no difficulties said that they had attended school, compared to 74% of those with some difficulty, and just 57% of those with a lot of difficulty. In South Africa, 45% of people with no difficulties reported being employed, compared to 40% of those with some difficulty, and 18% of those with a lot of difficulty.

Mitra said that this gradient of disparities from those with no difficulty to those with a lot of difficulty was one of their biggest findings.

“The degree of functional difficulties is associated with the degree of disadvantage, at least in education, in employment, and in some of these standard of living indicators, so that’s an important finding,” Mitra said. “That hasn’t been shown before.”

She said that this gradient shows the importance of not asking a “yes or no” question when it comes to disabilities.

“It implies that it’s important to measure inequalities for people on the spectrum [of disability],” she said.

Jaclyn Yap, a doctoral student in economics, who served as the data analyst for the initiative, said that understanding the varying needs of people with different levels of disabilities could help inform policy and resource decisions. The focus has always been on people with “a lot” of disability, she said, and while they study found that those people are struggling more, people with moderate disabilities still need services.

“They shouldn’t be taken for granted,” she said.

Putting the Work into Action

Mitra and her students said that they hope their work can be used by policymakers, researchers, and advocates to provide more resources and support for people with disabilities.

“We wanted it to be useful outside academia. And although we wanted it to be rigorous and scientific, we also took into consideration the general readers, which we’re hoping will advocate for persons with disability,” Yap said. “And also policymakers—they could use this as a means to help push for either laws or more budget for persons with disabilities.”

Funding for the project runs at least for another year, so Mitra said that they will include a new comparative analysis next year with different countries, including the United States.

“I’m hoping this will grow, because I’m hoping the data sets will become better and better, especially with the round of 2020 censuses,” Mitra said. “It’s starting with myself and seven students, and I hope it will grow into an international partnership among multiple universities.”

The Disability Data Initiative can be found at disabilitydata.ace.fordham.edu.

]]>“Today’s events are designed for recognition, celebration, and appreciation of the numerous contributors to Fordham’s research accomplishments in the past two years,” said George Hong, Ph.D., chief research officer and associate vice president for academic affairs.

Hong said that Fordham has received about $16 million in faculty grants over the past nine months, which is an increase of 50.3% compared to the same period last year.

“As a research university, Fordham is committed to excellence in the creation of knowledge and is in constant pursuit of new lines of inquiry,” said Joseph McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, said during the virtual celebration. “Our faculty continue to distinguish themselves in this area. Today, today we highlight the truly extraordinary breadth and depth of their work.”

Earning Honors

Ten faculty members, representing two years of winners due to cancellations last year from the COVID-19 pandemic, were recognized with distinguished research awards.

“The distinguished research awards provide us with an opportunity to shine a spotlight on some of our most prolific colleagues, give visibility to the research achievements, and inspire others to follow in their footsteps,” Provost Dennis Jacobs said.

Recipients included Yuko Miki, associate professor of history and associate director of Latin American and Latinx Studies (LALSI), whose work focuses on Black and indigenous people in Brazil and the wider Atlantic world in the 19th century; David Budescu, Ph.D., Anne Anastasi Professor of Psychometrics and Quantitative Psychology, whose work has been on quantifying, judging, and communicating uncertainty; and, in the junior faculty category, Santiago Mejia, Ph.D., assistant professor of law and ethics in the Gabelli School of Business, whose work examines shareholder primacy and Socratic ignorance and its implications to applied ethics. (See below for a full list of recipients).

Diving Deeper

Eleven other faculty members presented in their recently published work in the humanities, social sciences, and interdisciplinary studies.

Jews and New York: ‘Virtually Identical’

Images of Jewish people and New York are inextricably tied together, according to Daniel Soyer, Ph.D., professor of history and co-author of Jewish New York: The Remarkable Story of a City and a People (NYU Press, 2017).

“The popular imagination associated Jews with New York—food names like deli and bagels … attitudes and manner, like speed, brusqueness, irony, and sarcasm; with certain industries—the garment industry, banking, or entertainment,” he said. “

Soyer quoted comedian Lenny Bruce, who joked, “the Jewish and New York essences are virtually identical, right?”

Soyer’s book examines the history of Jewish people in New York and their relationship to the city from 1654 to the current day. Other presentations included S. Elizabeth Penry, Ph.D., associate professor of history, on her book The People Are King: The Making of an Indigenous Andean Politics (Oxford University Press, 2019), and Kirk Bingaman, Ph.D., professor of pastoral mental health counseling in the Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education, on his book Pastoral and Spiritual Care in a Digital Age: The Future Is Now (Lexington Books, 2018).

Focus on Cities: The Reality Beyond the Politics

Annika Hinze, Ph.D, associate professor of political science and director of the Urban Studies Program, talked about her most recent work on the 10th and 11th editions of City Politics: The Political Economy of Urban America (Routledge, 11th edition forthcoming). She focused on how cities were portrayed by the Trump Administration versus what was happening on the ground.

“The realities of cities are really quite different—we’re not really talking about inner cities anymore,” she said. “Cities are, in many ways, mosaics of rich and poor. And yes, there are stark wealth discrepancies, growing pockets of poverty in cities, but there are also enormous oases of wealth in cities.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Hinze’s latest edition will show how urban density did not contribute to the spread of COVID-19, as many people thought, but rather it was overcrowding and concentrated poverty in cities that led to accelerated spread..

Other presentations included Nicholas Tampio, Ph.D., professor of political science, on his book Common Core: National Education Standards and the Threat to Democracy (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018); Margo Jackson, Ph.D., professor and chair of the division of psychological and educational services in the Graduate School of Education on her book Career Development Interventions for Social Justice: Addressing Needs Across the Lifespan in Educational, Community, and Employment Contexts (Rowman and Littlefield, 2019); and Clara Rodriguez, Ph.D., professor of sociology on her book America, As Seen on TV: How Television Shapes Immigrant Expectations Around the Globe (NYU Press, 2018).

A Look into Migration

In her book Migration Crises and the Structure of International Cooperation (University of Georgia Press, 2019), Sarah Lockhart, Ph.D. assistant professor of political science, examined how countries often have agreements in place to manage the flow of trade, capital, and communication, but not people. While her work in this book specifically focused on voluntary migration, it also had implications for the impacts on forced migration and the lack of cooperation among nations .

“I actually have really serious concerns about the extent of cooperation … on measures of control, and what that means for the future, when states are better and better at controlling their borders, especially in the developing world,” she said. “And what does that mean for people when there are crises and there needs to be that kind of release valve of movement?”

Other presentations included: Tina Maschi, Ph.D., professor in the Graduate School of Social Service, on her book Forensic Social Work: A Psychosocial Legal Approach to Diverse Criminal Justice Populations and Settings (Springer Publishing Company, 2017), and Tanya Hernández, J.D., professor of law on her book Multiracials and Civil Rights: Mixed-Race Stories of Discrimination (NYU Press, 2018).

Sharing Reflections

The day’s keynote speakers—Daniel Alexander Jones, professor of theatre and 2019 Guggenheim Foundation Fellow, and Tony Award winner Clint Ramos, head of design and production and assistant professor of design—shared personal reflections on how the year’s events have shaped their lives, particularly their performance and creativity.

For Jones, breathing has always been an essential part of his work after one of his earliest teachers “initiated me into the work of aligning my breath to the cyclone of emotions I felt within.” However, seeing another Black man killed recently, he said, left him unable to “take a deep breath this morning without feeling the knot in my stomach at the killing of Daunte Wright by a police officer in Minnesota.”

Jones said the work of theatre teachers and performers is affected by their lived experiences and it’s up to them to share genuine stories for their audience.

“Our concern, as theater educators, encompasses whether or not in our real-time lived experiences, we are able to enact our wholeness as human beings, whether or not we are able to breathe fully and freely as independent beings in community and as citizens in a broad and complex society,” he said.

Ramos said that he feels his ability to be fully free has been constrained by his own desire to be accepted and understood, and that’s in addition to feeling like an outsider since he immigrated here.

“I actually don’t know who I am if I don’t anchor my self-identity with being an outsider,” he said. “There isn’t a day where I am not hyper-conscious of my existence in a space that contains me. And what that container looks like. These thoughts preface every single process that informs my actions and my decisions in this country.”

Interdisciplinary Future

Both keynote speakers said that their work is often interdisciplinary, bringing other fields into theatre education. Jones said he brings history into his teaching when he makes his students study the origins of words and phrases, and that they incorporate biology when they talk about emotions and rushes of feelings, like adrenaline.

That message of interdisciplinary connections summed up the day, according to Jonathan Crystal, vice provost.

“Another important purpose was really to hear what one another is working on and what they’re doing research on,” he said. “And it’s really great to have a place to come listen to colleagues talk about their research and find out that there are these points of overlap, and hopefully, it will result in some interdisciplinary activity over the next year.”

Distinguished Research Award Recipients

Humanities

2020: Kathryn Reklis, Ph.D., associate professor of theology, whose work included a project sponsored by the Henry Luce Foundation on Shaker art, design, and religion.

2021: Yuko Miki, Ph.D., associate professor of history and associate director of Latin American and Latinx Studies (LALSI), whose work is on Black and indigenous people in Brazil and the wider Atlantic world in the 19th century.

Interdisciplinary Studies

2020: Yi Ding, Ph.D., professor of school psychology in the Graduate School of Education, who received a $1.2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education for a training program for school psychologists and early childhood special education teachers.

2021: Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., professor of Economics and co-director of the Disability Studies Minor, whose recent work includes documenting and understanding economic insecurity and identifying policies that combat it.

Sciences and Mathematics

2020: Thaier Hayajneh, Ph.D., professor of computer and information sciences and founder director of Fordham Center of Cybersecurity, whose $3 million grant from the National Security Agency will allow Fordham to help Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Minority-Serving Institutions build their own cybersecurity programs.

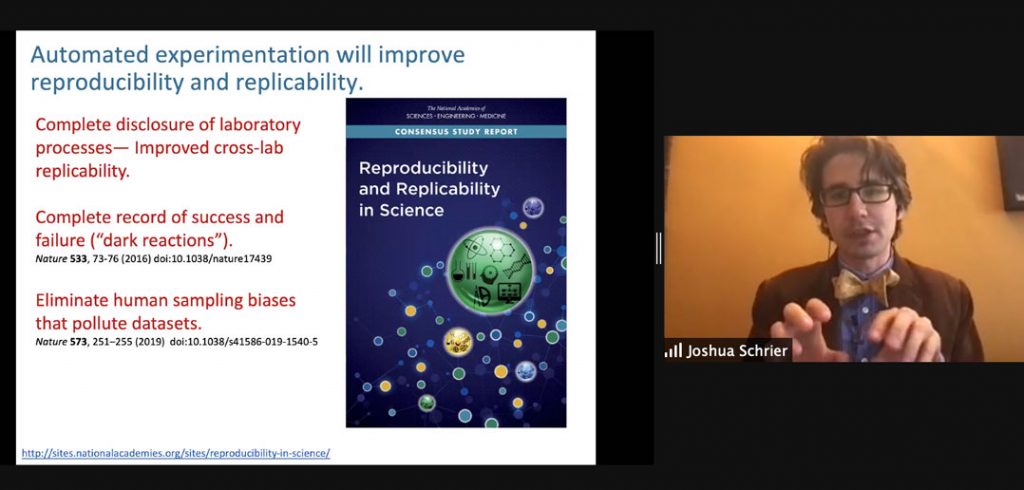

2021: Joshua Schrier, Ph.D., Kim B. and Stephen E. Bepler Chair and professor of chemistry, who highlighted his $7.4 million project funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency on perovskites.

Social Sciences

2020: Iftekhar Hasan, Ph.D., university professor and E. Gerald Corrigan Chair in International Business and Finance, whose recent work has included the examination of the role of female leadership in mayoral positions and resilience of local societies to crises.

2021: David Budescu, Ph.D., Anne Anastasi Professor of Psychometrics and Quantitative Psychology, whose work has been on quantifying, judging, and communicating uncertainty.

Junior Faculty

2020: Asato Ikeda, Ph.D., associate professor of art history, who published The Politics of Painting, Facism, and Japanese Art During WWII.

2021: Santiago Mejia, Ph.D., assistant professor of law and ethics in the Gabelli School of Business, whose work focuses on shareholder primacy and Socratic ignorance and its implications to applied ethics.

“Racism, sexism, and other ‘isms’ are not simply irrational prejudices, but long-leveraged, strategic mechanisms for exploitation that have benefited some at the expense of others,” he said.

Hamilton, the Henry Cohen Professor of Economics and Urban Policy and founding director of the Institute on Race and Political Economy at The New School, noted that in a just world, one’s race, gender, or ethnicity “would have no transactional value as it relates to material outcomes.” The pandemic made it abundantly clear that is not the case.

“We should recognize that the biggest pre-existing condition of them all is wealth itself,” he said.

Hamilton’s lecture, “A Moral Responsibility for Economists: Anti-Racist Policy Regimes that Neuter White Supremacy and Establish Economic Security for All,” was the second distinguished economics lecture, which was launched last year by the economics department’s climate committee as a way to enhance diversity and inclusion.

‘Dysfunctional Concentration of Wealth and Power’

Hamilton began by pointing out that even before the pandemic, the United States was afflicted by an “obscene, undemocratic, dysfunctional concentration of wealth and power.” Currently, the top .1% of earners in this country—defined as those earning $1.5 million a year—own as much of the nation’s wealth as the bottom 90 percent of earners. The bottom 50 percent of earners own 1% of the nation’s wealth, he said.

This has affected Black people and other people of color disproportionately, as they’ve been denied economic opportunity through official policies such as redlining in the 1950s and events such as the Tulsa Race Massacre in 1921. But the narrative of why Black Americans have been unable to attain wealth has not reflected this history, he said.

The Narrative is Wrong

“Much of the framing around the racial wealth gap, including the use of alternative financial service products, focuses on poor financial choices and decision-making on the part of largely Black, Latino, and poor borrowers. The framing is often tied to and derived from a culture of poverty thesis, in which Blacks are presumed to have a low value for and desire for education,” he said.

“The framing is wrong; the directional emphasis is wrong.”

The idea that education alone is the path to prosperity is itself belied by what Hamilton called the “property rights,” which are the advantages that whites have been granted through history by the government.

Disparities in Education and Health

Black college students today are saddled with an average of $53,000 in debt, while white students graduate with an average debt of $33,000. Black college graduates are actually overrepresented in graduate education, relative to their share in the population, he said, but this is not enough. On average, a Black family with a head of the household who dropped out of college still has less wealth than a white family where the head dropped out of high school, he said.

“The fact that a Black expectant mother with a college degree has a greater likelihood of an infant death than a white expectant mother who dropped out of high school, and a Black man with a college degree is three times more likely to die from a stroke than a white man who dropped out of high school—these are all examples of property rights in whiteness,” he said.

Hamilton said that reparations are a necessary remedy but would only be a start. Only by implementing a program such as baby bonds, where government creates investment accounts for infants that give them access to capital when they turn 18, would we get the bold, transformative, anti-racist, anti-sexist policies that are long overdue.

“We need a deeper understanding of how devaluing, or othering, individuals based on social identities like race relates to political notions of deserving and undeserving,” he said.

“The structures of our political economy and race go well beyond individual bigotry as a matter of course.”

Eye-Opening for Students

Andrew Souther, a senior majoring in economics and math at Fordham College at Rose Hill, said that the talk was eye-opening for him, as his senior thesis is focused on behavioral economics, where biases and discrimination are key concepts.

“The language that Dr. Hamilton used in basically describing racism as this very strategic collective investment, as one group strategically investing in this identity of whiteness which has a return and also extracts from other people—that is a really, really powerful concept,” he said.

“It really cuts at something much deeper and much more radical than just conversations about behavioral biases, which of course are important too.”

Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., a professor of economics, said Hamilton’s perspective was an example of a topic students at Fordham might not otherwise be exposed to in the course of their studies, a key goal of the series.

“At a time of extreme polarization in the United States, Dr. Hamilton’s scholarship and anti-racist policy proposals are more important than ever,” she said.

“He powerfully prompted us to think about the need to move from an economy centered on markets and firms to a sustainable moral economy, an economy with, at its core, economic rights, inclusion, and social engagement.”

The full lecture can be viewed here.

]]>

“Disabilities are often perceived as a small minority issue—something that affects a mere 1%. That’s not the case,” said Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., co-director of the minor program, founding director of the Research Consortium on Disability, and professor of economics.”

Around one billion people worldwide live with a disability, according to the United Nations, including one in four adults in the U.S. alone, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since the minor started in January 2019, students in the program have learned how disability and normality are understood and represented in different contexts, from literature to architecture to fashion. The curriculum also helps bring awareness to issues of access on Fordham’s campus and beyond.

“Our minor program gets students to think about what it means to have a disability and what the consequences of having a disability might be in society,” Mitra said. “It’s an essential part of thinking about inclusion and what it means to be an inclusive society—and yet, it’s a dimension of inclusion that we sometimes forget about.”

The program is designed to show undergraduates how to create more accessible physical and social environments and help them pursue careers in a range of fields, including human rights, medicine and allied health, psychology, public policy, education, social work, and law.

Among these students is Sophia Pirozzi, an English major and disability studies minor at Fordham College at Rose Hill.

“The biggest thing that I’ve taken away is that when minority rights are compromised, so are the majority … And I think when we elevate that voice and that experience, we come a little bit closer to taking into consideration that the only way to help ourselves is to help other people,” said Pirozzi, who has supervised teenagers with intellectual and physical disabilities as head counselor at a summer camp in Rockville, Maryland. After she graduates from Fordham in 2021, she said she wants to become a writer who helps build access for the disability community.

Now, in addition to the minor program, Fordham has a Research Consortium on Disability, a growing team of faculty and graduate students across six schools—the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the Graduate School of Education, the Graduate School of Social Service, the Gabelli School of Business, the Law School, and the Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education—who conduct and coordinate disability-related research at at the University.

Since this past October, the consortium has created new opportunities to connect faculty and graduate students working on disability-related research across the University and in the broader New York City area, including lunch meetings and new research studies. This month, it launched its new website. The consortium is planning its first symposium on social policy this November and another symposium on disability and spirituality in April 2021.

The consortium is a “central portal” for interdisciplinary research that can help scholars beyond Fordham, said Falguni Sen, Ph.D., professor and area chair in strategy and statistics, who co-directs the consortium with Rebecca Sanchez, Ph.D., an associate professor in English. That includes research on how accessible New York City hospitals are for people with disabilities, particularly in the COVID-19 pandemic.

“What has come to light very acutely is the whole notion of how vulnerable populations have been differentially affected in this COVID-19 [pandemic],” Sen said. “The emergency responses to that population have not necessarily been as sensitive or as broad in terms of access as we would like it to be … And we were already thinking about issues of crisis because of what happened in 9/11.”

The minor and the Research Consortium on Disability build upon the work of the Faculty Working Group on Disability: a university-wide interdisciplinary faculty group that has organized activities and initiatives around disability on campus over the past five years. The group has hosted the annual Fordham Distinguished Lecture on Disability and several events, including a 2017 talk by the commissioner for the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities.

“Fordham is known for community-engaged learning and how its work, both the research that we do and others, have relevance directly in people’s lives,” said Sen. “And that’s what we are trying to do.”

]]>At Fordham, about one-third of both undergraduate economics majors and economics faculty are women, while the graduate economics population is made up of about 50% women, according to Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., professor of economics at Fordham and co-director of the disabilities studies minor.

Despite the fact that the University is slightly above the national average in both of those areas, the economics department launched a “climate committee” in 2018 to examine these issues related to underrepresentation and develop resources to “enhance diversity and inclusion in economics at Fordham,” Mitra said.

One of their first initiatives is the “Inaugural Distinguished Lecture in Economics,” featuring Janet Currie, Ph.D., the Henry Putnam Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at Princeton University and co-director of Princeton’s center for health and wellbeing. The event will take place on Thursday, Dec. 5 from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. at the McNally Amphitheater at the Gabelli School of Business. The talk will be followed by a question-and-answer session and a reception.

The event was sponsored by the economics department, the Office of the Chief Diversity Officer, the faculty of arts and sciences deans, the Economics Society, and the faculty working group on disability. Funding was provided through the economics department, Chief Diversity Officer, and the faculty of arts and sciences deans.

Mitra said they wanted to bring in Currie because her research “goes beyond this narrow and misleading understanding of what economics is about.”

“Currie is a scholar whose work spans labor, public, and health economics,” she said. “She has made fundamental contributions in many areas and is best known for her work on public policy issues affecting child health and well-being. Through this lecture, we would like students to get a taste of the breadth of her illuminating research.”

That’s also why the focus of the lecture, “Child Health and Human Capital,” does not fit with what is often perceived as an economics topic.”

“There is the commonly held notion out there that economics is about money, business, or material resources,” she said. “Economics is a social science that provides ways to understand human behaviors and can pay attention to ethics. It can help contribute to solving a variety of issues, such as improving child health by considering the sorts of economic arrangements and public policies that serve to improve child health.”

Mitra said that the goal is to make this the first in a series of lectures that will feature a “diverse set of scholars that undergraduate students may not hear about” and “scholars that use a variety of approaches and paradigms.”

In addition to offering events, Mitra said that the climate committee is also working to attract potential students who might not have thought about majoring in economics.

“One focus of this committee is to develop initiatives and resources that may help more diverse candidates study economics or at least consider studying economics at the undergraduate level,” she said. “We are considering new course offerings to that end as well as events.”

While the event is open to the entire Fordham community, the program is specifically geared towards undergraduate students who are just starting out in economics.

“Our main purpose is to expose students to a topic and a scholar that they might not typically study in the introductory courses in economics,” Mitra said.

To RSVP, please visit www.curiefordham.eventbrite.com. To learn more about the event, visit www.fordham.edu/info/20930/economics.

]]>A research analyst works to improve the criminal justice system

Whether she’s studying incarcerated people or people with disabilities—or both—Navena Chaitoo tries to shed light on the many dimensions and nuances of large systemic problems.

Chaitoo works as a research analyst in the Center on Sentencing and Corrections at the Vera Institute of Justice, a national nonprofit that seeks to drive change in the justice system. Specifically, she analyzes data and works with prison jurisdictions—at their request—to reduce the use of solitary confinement.

“If you really think about solitary confinement—you’re alone in a cell, you have no access to programming, to other individuals … what does that do to your mental health? When we talk with people who have been through solitary, one of the things that comes out of it is just how deeply traumatic it is,” she says, adding that it does not help rehabilitate prisoners. “What leads to rehabilitation is pro-social behavior.”

She also researches the level of confinement of prisoners with disabilities and their access to services, expanding on a theme that has run through her work since her college days. As a person with profound hearing loss, Chaitoo has had to work to get the accommodations she needs—including at Fordham, where she went a semester without stenography services in her classes.That experience led to her work on a research paper that she began at Fordham in which she examined disability and multidimensional poverty in America.

“Currently, poverty is measured by what you have in your pocket—how much income you have … it’s not about your capabilities,” she said. The paper, co-authored with Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., associate professor of economics at Fordham, among others, looked at how a person’s disability might impact their ability to earn a living wage and their access to food, education, and participation in the political process.

While at Fordham, Chaitoo won a highly competitive graduate fellowship award from the National Science Foundation, which fully funded her graduate studies at Carnegie Mellon University, where she earned a master’s degree in public policy and management.

After graduate school, she got a job as a researcher with the Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services, where she assisted with the research and development of the Manhattan Supervised Release Program—an alternative to pre-trial detention for those who can’t make bail.

“I ended up loving it, and wanting to get more out of the research behind it. So I transferred to Vera,” Chaitoo says. That concept of more—or magis in Jesuit terms—is one she reflected on in college. “When you really think about living the Fordham mission,” she says, “it’s about how can I do this better, how can I serve people better?”

]]>At Fordham, the celebration began a day early with an interdisciplinary symposium spotlighting faculty and students research focused on disability. The Dec. 2 event, “Diversity and Disability: A Celebration of Disability Scholarship at Fordham,” also marked the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Matthew Diller, dean of Fordham School of Law and the Paul Fuller Professor of Law, discussed how disability law influences people’s participation in the workforce. This participation, Diller said, is socially as well as economically important, because work signifies social status.

“Work is central to how we think about people, their role in society, and whether they are successful members of that society,” Diller said. “There is a social expectation that you should be in the workforce, and if you’re not, then you’re an underperforming member.”

Not everyone can fulfill that expectation, Diller said, so the law allows for some people to be excused from work owing to certain situations or conditions, such as a disability. Some people, however—including people with disabilities—are excluded from work altogether as the result of prejudice, discrimination, or other barriers that prevent them from fully participating in society.

“If we judge social worth by whether someone works, but then exclude some people from the workforce, then we’re inherently denigrating their social worth,” he said.

The value of the ADA, Diller said, is that it focuses on creating systems that integrate people with disabilities into the workforce, thereby restoring their right to work.

However, there remains room for improvement, Diller said. For instance, up until Congress substantially amended the law in 2008, courts regularly impeded the ADA’s enforcement by making the definition of disability extremely narrow. Many plaintiffs seeking excusal from or accommodations for work lost their cases on the grounds they were not disabled—an approach Diller said was “misguided.”

Photo by Dana Maxson

Christine Fountain, PhD, assistant professor of sociology, and Rebecca Sanchez, PhD, assistant professor of English, also presented.

Fountain is doing research with scientists from Columbia University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the sociological aspects of autism, particularly how a noncontagious illness has reached epidemic proportions and who is being most severely affected by it.

Autism, the group has found, is more prevalent in children of wealthy and well-educated parents, and that wealth and education play a role in how quickly and to what extent an autistic child improves developmentally.

Sanchez discussed her new book Deafening Modernism: Embodied Language and Visual Poetics in American Literature (New York University Press, 2015), which argues that “deaf insight,” that is, the “embodied and cultural knowledge of deaf people,” is not an impairment, but an alternative way of thinking and communicating.

She offered the example of Charlie Chaplin’s 1936 silent film Modern Times. Chaplin, Sanchez said, deliberately chose to avoid the new “talkie” technology because silent pictures allowed for “a universal means of expression.” The plot of the film itself, she said, bespeaks the dangers of forcing people to express themselves in homogenized ways.

The event also included poster presentations by two doctoral students, Xiaoming Liu and Rachel Podd, and Navena Chaitoo, FCRH ’13.

Photo by Dana Maxson

Elizabeth Emens, PhD, the Isidor and Seville Sulzbacher Professor of Law at Columbia Law School, offered the keynote presentation, “Disability Law Futures: Moving Beyond Compliance.”

The event was sponsored by the Office of Research and by the Faculty Working Group on Disability, led by Sophie Mitra, PhD, associate professor of economics. The group connects Fordham faculty who are researching some aspect of disability.

]]>

Photo by Angie Chen

In the face of many disparate initiatives, ultimately it falls upon the central government to develop policy and monitor the activities of NGOs, said Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Economics and Fordham’s Center for International Policy Studies.

“The earthquake led to injuries and trauma, leading to more physical and mental disabilities,” said Mitra.

In an attempt to address the needs of the disabled, Gerald Oriol, Jr. was appointed Haiti’s secretary of state for the integration of persons with disabilities in 2011. Oriol, who has a disability, promptly set about redefining perceptions and collecting new data on disability via the country’s official census, set to take place later this year.

The secretary has tapped Mitra, a specialist in the economics of disability, to help hone the census questionnaire and advise on policy.

Mitra has advised that language thus far drafted in the census, which before framed disabilities as “impairments,” to be recast as “limitations on functionings.”

She has been involved in the drafting of new questions based on research from the Washington Group on Disability Statistics. A question like “Do you have difficulty seeing, even if wearing glasses?” could be answered with, “No – no difficulty,” “Yes – some difficulty,” “Yes – a lot of difficulty,” or “Cannot do at all.” The more nuanced a survey is, she said, the greater assurance that more than just the extreme cases make it into the record.

Mitra said that disability biases are not limited to Haiti.

“Whether in high- or low-income countries, negative attitudes with respect to what people with disabilities can do are still common. But in high income countries, progress has been made on the physical aspects of integration,” she said.

While cities like New York have highly visible accommodations for persons with disabilities, developing countries have more limited resources to adapt their infrastructure.

“There are the physical aspects of integration and accessibility, but then there are the social attitudes that act as barriers,” said Mitra. “Fighting the biases will affect people’s likelihood of being successful. It needs to be about physical access and social access.”

Mitra’s Haiti experiences will find their way back into Fordham’s classrooms.

“My work so far has been primarily in producing research and this is a good way to show students how research can practically influence policy,” said Mitra.

]]>

As Haiti passes the third anniversary of the earthquake, thousands of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have been motivated to help solve Haiti’s many recovery problems, including how to best serve its disabled community.

In the face of many disparate initiatives, ultimately it falls the central government to develop policy and monitor the activities of NGOs, said Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Economics and Fordham’s Center for International Policy Studies.

“The earthquake led to injuries and trauma, leading to more physical and mental disabilities,” said Mitra.

In an attempt to address the needs of the disabled, Gerald Oriol, Jr., was appointed Haiti’s secretary of state for the integration of persons with disabilities in 2011. Oriol, who has a disability, promptly set about redefining perceptions and collecting new data on disability via the country’s official census, set to take place later this year.

The secretary has tapped Mitra, a specialist in the economics of disability, to help hone the census questionnaire and advise on policy.

Mitra has advised that language thus far drafted in the census, which before framed disabilities as “impairments,” to be recast as “limitations on functionings.”

She has been involved in the drafting of new questions based on research from the Washington Group on Disability Statistics. A question like “Do you have difficulty seeing, even if wearing glasses?” could be answered with, “No – no difficulty,” “Yes – some difficulty,” “Yes – a lot of difficulty,” or “Cannot do at all.” The more nuanced a survey is, she said, the greater assurance that more than just the extreme cases make it onto the record.

Mitra said that disability biases are not limited to Haiti.

“Whether in high or low income countries, negative attitudes with respect to what people with disabilities can do are still common. But in high income countries, progress has been made on the physical aspects of integration,” she said.

While cities like New York have highly visible accommodations for persons with disabilities, developing countries have more limited resources to adapt infrastructure.

“There are the physical aspects of integration and accessibility, but then there are the social attitudes that act as barriers,” said Mitra. “Fighting the biases will affect people’s likelihood of being successful. It needs to be about physical access and social access.”

Mitra’s Haiti experiences will find their way back into Fordham’s classrooms.

“My work so far has been primarily in producing research and this is a good way to show students how research can practically influence policy,” said Mitra.

]]>

Photo by Angie Chen

According to the latest U.S. Census projection, people with disabilities accounted for 19.3 percent of the American population. In India, the estimate was 2.1 percent, and in South Africa, it was 4.3 percent.

To Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., assistant professor of economics, such statistics were beguiling; logic would dictate that an industrialized, affluent nation should show fewer, not more, people with disabilities (PWDs).

But Mitra soon discovered that people with disabilities were there, all right: they just weren’t being counted. They constituted, in effect, an invisible minority.

“There is a lack of awareness for how big this group really is,” said Mitra, a native of France who worked with the World Bank and the Overseas Development Institute before coming to the United States to do post-doctoral analysis in labor economics. “When I decided to research disability in developing countries, I discovered that it is very hard to find quality data.

“We are talking about the poorest of the poor, those often shut out of employment opportunities. Because they are not visible in society, there is little awareness that this group needs to be studied.”

PWDs include those with limited vision, hearing impairment, mental retardation or mental illness, difficulty with physical activities such as walking or carrying, and difficulty in school, housework or other daily activities.

In the past six years, Mitra, a specialist in developing economies, has made use of new data sources to study the invisible minority in developing nations. As a microeconomist, her research is data-based and impartial. As a human being, Mitra hopes that the results of her research will help empower groups who are socially and economically ostracized from opportunities to be productive.

In South Africa, Mitra looked at how a social pension program, the Disability Grant (DG) for working-age people who could not work due to a disability, was affecting its intended group and the nation’s workforce. Between 2001 and 2004, some South African provinces eased their screening rules for the DG, and the number of beneficiaries tripled. By 2005, close to 4 percent of the population was on DG.

“Some observers said that this was one of the worst social assistance programs ever, that anybody could get on disability,” Mitra said.

Comparing several provinces with lenient screening practices against one retaining the original screening test, Mitra discovered that there was little evidence that the new set of rules spawned program dependency. Labor market behaviors remained largely unchanged and the program was well-targeted, Mitra said, compared to other disability programs around the world.

However, her data revealed a decrease in the employment of one group—working-age PWDs who could work. Given increased access to DG, some may have chosen not to work, or even to look for work.

The findings, Mitra said, can help grassroots NGOs target services to encourage people with disabilities who can still work, to rejoin the labor force.

“While it is great to have a social grant available if people are poor and have no ability to work, you also want to empower people to be independent,” said Mitra.

India has experienced tremendous economic growth in the last decade, yet, according to Mitra, the nation had scant raw data on the economic well-being of people with disabilities.

Mitra collaborated with the World Bank and some NGOs to conduct a household survey in rural areas of the Tamil Nadu province—one of India’s most productive areas—that would explore employment among male PWDs.

Mitra noted that in the U.S., Great Britain and Sweden, there is evidence that the wages of PWDs are about 30 percent lower than those of people without disabilities. In India, however, Mitra discovered that PWDs in the Tamil Nadu work force faced little, if any, wage discrimination.

“In an Indian village labor market, wages are pretty rigid,” said Mitra.

While the wage gap was minimal, however, the employment gap was huge. The study revealed strong negative attitudes toward PWDs’ employment potential. The negative attitudes, said Mitra, contribute to the low employment rate among the PWDs.

Although India’s Disability Act of 1995 offers incentives to employers who hire PWDs for a percentage of their work force, most employers have not climbed on board. And Mitra’s previous research has revealed that most new programs promoting employment for the disabled are urban-centric.

“The attitude of the government has often been, ‘We have so many problems, we can’t deal with these vulnerable groups; we have too much to handle with the overall economy,’” Mitra said.

Both studies, Mitra said, will bring more visibility to a population that is up to five times larger than previously thought. The India study, which recommends more educational efforts to reduce the stigma against PWDs, has already been incorporated in a new governmental plan.

“The driving force to my research is that it produces knowledge that informs policy and program development for vulnerable groups,” she said. “That is my hope.”

– Janet Sassi

]]>