]]>The Fordham University historian Magda Teter follows the spread of these deadly allegations, which exploded after the successful Trent prosecution, in her 2020 book, Blood Libel: On the Trail of an Antisemitic Myth. The work’s accompanying maps trace more than 100 such accusations, delineating them by criteria such as whether there were “legal proceedings” (73 yes, 30 no) or “Jews killed” (31 yes, 55 no, 13 unknown).

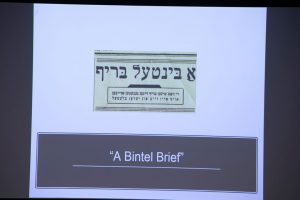

Ayelet Brinn, Ph.D., Rabin-Shvidler Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, posed these questions to the audience in her lecture about the American Yiddish press at Lincoln Center on Feb. 13.

Brinn, who was introduced by Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies and professor of history Magda Teter, Ph.D., said that before talking about the significance of advice columns in Yiddish newspapers, it was important that the audience “think about the various ways people read and interact with advice columns and the fact that this is a media that is set up to be read by different readers in different ways.”

The Rise of the Yiddish Press in America

Yiddish speakers in the United States increased significantly in the second half of the 19th century with a wave of mass immigration from Eastern Europe, and by the 1920s, Yiddish newspapers were a popular option for immigrants seeking guidance in their new home. Many Jewish immigrants never read newspapers before coming to America, said Brinn, but they began to see them as an indispensable part of their lives for three reasons.

First, they helped acclimate readers to American life. Second, they created a sense of community by binding Yiddish readers to each other based on what they read. Lastly, they taught people who didn’t normally read newspapers that they could be informational and provide guidance on how to navigate their daily lives.

A good example, she said, is A Bintel Brief, which was one of the most popular advice columns of its time. Abraham Cahan, the longtime editor of the Forward, the most popular Yiddish daily, introduced A Bintel Brief to the paper in 1906, after asking readers to write to the paper with stories from their lives in the hopes of encouraging their relationship with the newspaper.

One letter in particular peaked Cahan’s interest, Brinn said. Written by a housewife, the letter sought the paper’s advice on how to confront her neighbor, who she suspected had stolen and pawned her husband’s watch. Interestingly, the woman was not upset, but “described her empathy for the poverty that drove her neighbor to steal, recognizing that this neighbor was also a poor worker,” she said.

Cahan was excited by this letter because it was written by an underserved demographic that he wanted to attract to the paper, and the emotional aspect of it was exactly the type of content he was looking for to better model his paper after American papers.

Success Brings Controversy

As A Bintel Brief began to increase in popularity, the authenticity of its letters was called into question. “Many Yiddish journalists, especially his loudest critics, assumed that the improvements editors made to Bintel submissions went beyond the correction of language and extended either to rewriting submissions or even fabricating letters when the Forward did not receive letters that fit the themes Cahan or his staff wanted to explore,” Brinn explained.

Since not all submissions were printed and the submissions were never kept in records by the Forward, there isn’t enough evidence to support either claim that the letters were real or fake.

“I’m inclined to believe that the truth lies somewhere between these extremes,” Brinn said. “Some letters were fabricated, some were real, and most letters that were real were significantly edited by the Forward staff.”

During a Q&A session after the presentation, an audience member confirmed that they had friends who actually read columns such as A Bintel Brief, and noted that “it didn’t really matter to those people if the letters were true or if they weren’t true. The advice didn’t matter either. It was really entertainment.”

Brinn heartily agreed.

“I think that one of the really important things about advice columns is that people could read them in all of these different ways,” she said.

“They did offer people advice that they could use in their lives, but other people could read these same columns for entertainment purposes.”

The exhibition, which was unveiled at an open house on April 16 in the O’Hare Special Collections Library, will run through the end of May. A second open house will be held on May 7 at 6 p.m.

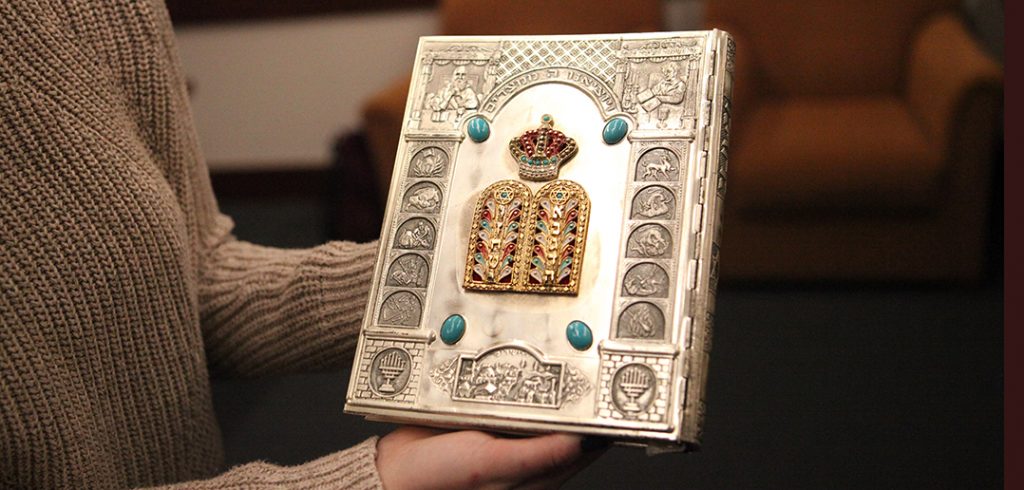

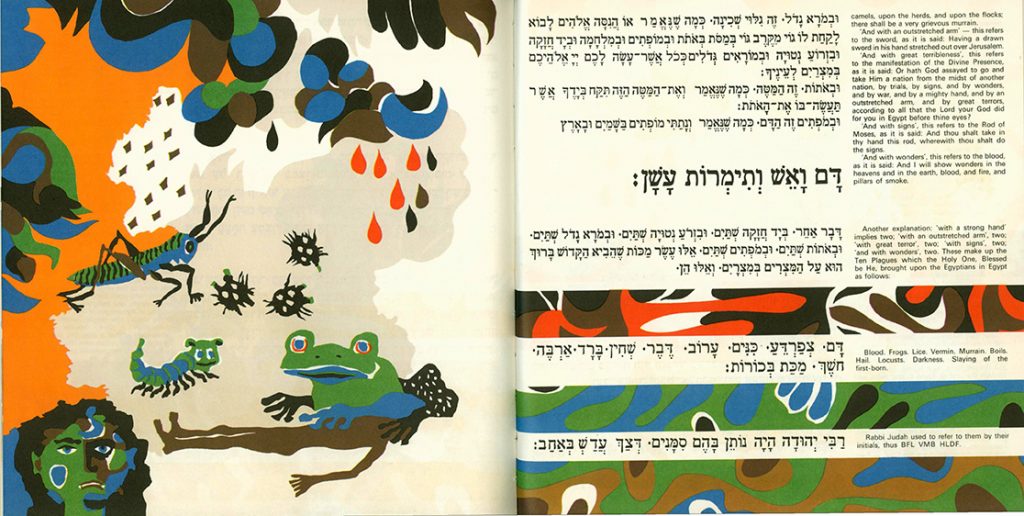

Teter has been growing Fordham’s collection of Hebrew texts for some time now, and the Haggadot (plural of Haggadah) reflect an overall curatorial vision of mixing the common household texts with high-quality facsimiles of The Barcelona Haggadah and from the Rothschild Miscellany, donated by longtime library patron James Leach, M.D. As in years past, the Maxwell House Coffee Haggadah, a common sight in many a middle-class Jewish home, sits near rare 18th-century versions.

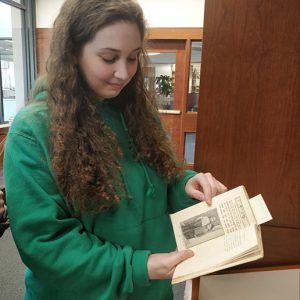

The exhibit was co-curated with Rose Hill seniors Emma Fingleton and Zowie Kemery, both Jewish studies minors, and sophomore Margaret Keiley. The project began at the start of the semester in early February. The students met with Teter to see and, more importantly, handle the texts.

“It’s not behind a glass plane; it’s right in front of you and you can touch it,” Fingleton said of one of the texts at the time.

Indeed, as Fingleton and Keiley grazed their hands across the paper, they remarked on the impressions left behind by an 18th-century letterpress.

“People actually use these objects, it’s very different from reading it online on a PDF,” said Keiley.

This year’s exhibition differs from the 2016 show, which expanded on Jewish-Christian relations. Instead, this show takes visitors on a world tour through nations and time. There were plenty of texts to choose from. The collection includes Haggadot from Egypt, Ethiopia, Sweden, Germany, and Holland. There is a vegetarian-focused Haggadah called The Liberated Lamb. There are Haggadot that were distributed at displacement camps just after World War II. And there are two from the same publisher that seem exactly the same except for one detail on the title page: One was printed in Palestine in 1948, just before the State of Israel was created; the other was printed in the exact same geographical place in 1953, when it was Israel.

“It’s a global story told in different languages, but the same culture,” said Teter.

Some of the pages come alive with past use. In particular, there are the pages with wine stains, which represent a moment during the Seder when the plagues are mentioned and “you put a finger in the glass of wine and sprinkle it on the text,” said Teter. It was a particularly moving gesture to the students.

“It all resonates in ways that remind me of archeology. It brings you to their perspective, even if it’s something as simple as a wine stain,” said Fingleton. “I feel more open towards the value these things have. It really impacts your view.”

]]>

“It’s very exciting and it strengthens our connection with another major cultural institution,” said Magda Teter, Ph.D., Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies and professor of history.

The Fordham-NYPL Fellowship Program in Jewish Studies is made possible by the Eugene Shvidler Gift Fund and additional gift funds to Jewish studies.

“The library has quite a number of fellowships, but there’s not something special for the Dorot Division,” said Stephen D. Corrsin, Ph.D., curator of both the Dorot Jewish Division and the Slavic, Baltic, and East European Collections.

The Dorot Division was formed two years after the library was founded in 1895 and was the library’s first special collection, he said. With over 300,000 books and serials, it stands as one of the most significant collections of Judaica in North America.

“I know that scholars will find all sort of things here. Sometimes it’s serendipitous, sometimes they’re looking for something specific,” he said.

From a collection of 15th-century books published at the dawn of the printing press called incunables to microfilms of 20th-century Jewish newspapers from around the globe, the library presents a rare chance for scholars to study materials that have yet to be digitized, Corrsin said.

“We get people dropping by who just want to see something unusual, and if we have a facsimile we’ll bring it out,” he said. “But we wouldn’t bring out an incunable for a tourist. The scholar has a presumed need for the original item.”

Teter said that while Fordham Libraries’ Archives and Special Collections continues to grow its Judiaca collection, the library doesn’t yet have the resources to support the world class Jewish scholarship that the Dorot Division can provide. But Fordham can now facilitate visas for international scholars to gain access to the division; in turn, the University will then showcase their findings at lectures and faculty seminars.

“Research in the humanities and social sciences is underfunded and this program will enable scholars who we would love to come to New York City to come and share their research,” said Teter. “The New York Public Library will be their research lab and Fordham will be the place where their exciting conversations happen.”

In addition to the fellowship program, the University will host its first joint Fordham-NYPL program on March 29 with a talk by NYPL Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center Fellow Natan Meir, Ph.D., on “Stepchildren of the Shtetl: Destitute and Disabled Outcasts of East European Jewish Society, 1800-1939.”

“This is an innovative partnership between two institutions to share resources and promote Jewish scholarship,” said Magda Teter, Ph.D., the Eugene Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies and professor of history.

Teter said that the two universities were already collaborating at workshops focused on early modern Jewish history, where students from the two schools met at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus for scholarly discussion.

“This builds on that relationship and deepens the research,” she said.

Scholars in all fields of Jewish studies are encouraged to apply. Applicants must have a thorough command of Hebrew and have earned a doctoral degree sometime between June 2013 and June 2017.

Fellows will be expected to be in residence from September 2017 to May 2018, teach one undergraduate course per semester, give one lecture, and hold a faculty seminar.

This fellowship has been made possible by the Stanley A. and Barbara B. Rabin Postdoctoral Fellowship Fund at Columbia University and the Eugene Shvidler Gift Fund at Fordham University.

The application process is open through January 30, 2017 and can be accessed by writing to [email protected].

]]>

The program will seek to understand Jewish history and culture within the larger framework of Jews’ interaction with other religions, particularly among Jews and Christians. It will further strengthen Fordham’s commitment to the Jewish studies program, which came into its own after Eugene Shvilder made a generous gift to establish a named chair in 2013.

Magda Teter, PhD, the Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies and professor of history, described the new minor as “very robust.”

“’There are more than 10 members of the faculty who can cover all areas of Jewish history from antiquity to modern United States, Israel, and Europe,” said Teter.

Stephen Freedman, PhD, provost of the University, said what makes Fordham distinct among Jewish studies programs in New York City is “that we are a Jesuit institution.”

“Studying Jewish culture and Jewish themes is a way for all of us to understand our own traditions,” said Freedman. “In these explorations of differences you bring out the value and the similarities, and by exploring them you respect them.”

“There is so much shared tradition and an amazing amount of overlap.”

In another unique arrangement, all of the University’s Jewish studies students will have free access to the Jewish Museum of New York and the Museum of Jewish Heritage—A Living Memorial to the Holocaust. Many of the museums’ exhibitions and programs will be woven into the coursework, said Teter.

“We are honored to establish a partnership with Fordham and are excited about potential collaborative projects,” said Elizabeth Edelstein, director of education at the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

In addition to the new minor, Teter said that the Jewish studies program has received two grants from the American Academy for Jewish Research, where she was inducted as a fellow. The grants will support two collaborative projects between Fordham faculty and faculty from other New York City institutions.

One grant will support a working group, titled “Interdisciplinary Approaches to Jewish Orthodoxies, Society and Culture,” and will be led by Ayala Fader, PhD, associate professor of anthropology, and Isaac Bleaman, a doctoral candidate at New York University. The group is geared toward research on contemporary Jewish Orthodoxies, with an emphasis on North America, said Teter. The second grant will go toward an early modern workshop that will focus on working with primary sources via an interactive seminar format. Both groups will meet regularly at Fordham in the 2016-2017 academic year.

A series of public lectures on Jewish themes will be announced at summer’s end that will bring leading scholars from around the globe to campus.

“When we develop a minor such as this, it’s a first step to something broader and much more programmatic,” said Freedman. “Students will be able build out from these relationships, beyond the University and beyond New York.”

]]>

Magda Teter, PhD, the Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies, mounted the exhibition, her second this year, with Fordham Libraries in the O’Hare Special Collections Library at the Rose Hill campus.

In the exhibition, however, she said the sacred is counterbalanced by the profane, as it captures both the meaning the holidays have had for Jews and Christians, and displays their painful convergence through several items that depict nearly 600 years’ worth of anti-Jewish imagery.

Teter said that she didn’t want to gloss over the reality of the violence and hatred that Christians subjected Jews to during Easter and Passover festivals. Some of the materials in the show served as propaganda to stoke hatred of the Jews.

Some of the images are disturbing.

There are several depictions of a child being bled by Jews. A frequent anti-Semitic accusation against Jews was that they murdered Christians for their blood and used it in Passover rituals, an accusation known as the blood libel. Some of the images were inspired by the cult of Simon of Trent, a boy whose disappearance around Easter in 1475 was blamed on the Jews of this northern Italian town. Many Catholics venerated Simon, until in the aftermath of the Church’s Vatican II the cult of the boy was abolished.

Among the items on display are:

- engravings from two editions of the famous 15th century world chronicle that portray the bleeding of a child, with images of Jews as grotesque characters

- the Easter issue of an Italian magazine, La difesa della razza (The Defense of Race), from 1940 that once again return to the theme of blood libel;

- German currency from 1922 that celebrates burning Jews;

- an 1884 parody of the Haggadah by German artist Carl Maria Seyppel.

Teter noted that Fordham is an appropriate setting for the exhibition, as the Jesuits are not known for shying away from difficult issues.

What is disturbing is balanced by beauty, however, as precious facsimiles of the famous 14th-century Barcelona Haggadah, the Gradual of Gisela, and the magnificent 13th-century Biblia de San Luis are also on display. All are gifts of longtime library patron James Leach, MD. The books use contemporary color printing methods to achieve exacting color replications. The gold leaf, however, is applied by hand and can be found throughout both texts.

Although not an alumnus, Dr. Leach has developed a relationship with Fordham based on his love for the Church and for lifelong knowledge, he said. He remembers the first time he heard Mass in Latin at Holy Trinity Church in Passaic, New Jersey. From there his interest in medieval texts and manuscripts grew, he said.

“I think people say you see God in church architecture, and in the stained glass, but God is also in the illuminations alongside the printed word,” he said.

The aesthetic and intellectual intensity of the exhibit’s three main showcases are complemented with a display of ephemera as well. Some ephemera alongside the back wall of the special collections gallery includes Haggadot in many languages, including in Arabic and Amharic. There are also a few printed as commercial promotions for Streit’s Matzos and Maxwell House Coffee—which are ubiquitous to American Jewish households, said Teter, and which often became household keepsakes.

]]>The series features high-profile scholars from both the United States and abroad, including Israel and Poland, said Magda Teter, PhD, the Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies. There are two notable lectures in March to be held at Fordham Law.

.

“We’ll be covering a diverse range of topics—from north African Jewish communities to contemporary museum interpretations,” she said.

On Wed., March 2 at 6:30 p.m., award-winning authors Marc Epstein, PhD, professor of religion at Vassar College, and Sara Lipton, PhD, professor of history at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, will participate in “Jews in Medieval Art: A View From the Inside and Outside.” The scholars will look closely at the medieval origins of anti-Jewish iconography.

Lipton has researched how medieval Christians’ manner of worshiping the suffering Christ led to negative portrayals of Jews in art, said Teter. Epstein has studied how Jewish art and iconography are complicated because of an “ostensible biblical prohibition against visual representations.” Epstein’s work, like those of other scholars whose work focuses on Jewish art, contradicts the perception that Jews did not represent themselves in art.

On Mon., March 14, at 5:30 p.m., Moshe Rosman, PhD, professor of history at Bar Ilan University in Israel, will discuss how contemporary Jewish museums interpret the Jewish story in the age of smartphones and the trend at contemporary history museums to eschew artifacts in favor of multimedia, said Teter. In “How to Tell the Story: Jewish Museums, Jewish History, Jewish Metahistory,” Rosman will analyze five Jewish historical museums.

Teter said that Rosman has changed the study of Eastern European history in Poland by promoting the study of Jewish history in tandem with the nation’s economic history, as they are both “interdependent stories.”

He also revolutionized the study of Hasidism, she said. The scholarly field was solely dependent on Jewish sources until Rosman included research from the Polish state archive.

“He entirely changed the way we see how Hasidism is organized,” she said.

]]>The inaugural holder of Fordham’s Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies, Magda Teter, PhD, posed the provocative question at her installation on Nov. 17.

Teter assumed the chair earlier this year with the task of building Jewish Studies at Fordham. In her lecture, “From Alienation to Integration: Rethinking Jewish History,” she proceed to blur perceived historical divisions between Jewish and non-Jewish societies and histories, arguing that the perception of their separate histories was the result of 19th-century historians efforts to promoting newly formed national identities.

Jews, in fact, were far more integrated in the pre-modern Europe than has often been portrayed, she said. The idea of Jews being alienated and only recently integrated needed to be rethought.

“The theological concept of exile played a crucial role,” she said. “It implied that Jews were sojourners and foreigners in the lands they had lived in for centuries.”

She said that in Europe, the approaches to modernity emphasized Jewish integration, and yet the Jews remained marginal in general histories of the continent. History, she said, needs to be examined on its own terms without projecting contemporary views onto it. Such a reading would lead to an understanding that Jewish and Christian societies were interdependent. In light of such overlapping histories, she said, one history cannot be understood without the other.

For example, in 16th-century Strasburg, the presence of Jews changed the dynamic of the fraught relationship between Protestants and Catholics because the two religions had to make policy together as it related to the Jews.

In 17th-century Italy, Jews and Christians met in taverns where they would “sit, drink, argue, and sing,” she said. Eating, drinking, and dancing often led to sexual encounters and long term relationships.

“This caused more than a headache for Christian authorities as well,” said Teter, adding that such revelry triggered new legislation and new Jewish laws.

Among Jews, those enjoying the delights were not simply rebels disregarding the commandments, though they were indeed violating Jewish and Christian law.

Among Jews, those enjoying the delights were not simply rebels disregarding the commandments, though they were indeed violating Jewish and Christian law.

“Surely they disregarded commandments, defied existing laws, sometimes endangering their lives, and were indeed ‘abandoning themselves to physical pleasure,’” said Teter. “But this was because it was part of daily life—not a result of ‘freethinking behavior’ as such behavior would be interpreted later in the 18th century and beyond.”

Jews became “part of daily life” in an integrated fashion, a fact often overlooked by contemporary historians, she said. It underscores the difference between the pre-modern and modern Europe, she said, as well as much about what we know in Jews’ and Christians’ quotidian lives.

“There is no doubt that modern and pre-modern periods are different. But ‘integration’ as such can no longer be seen as ‘a basic criterion of the modern period.’ It is clear now that the traditional narrative of Jewish insularity, victimhood, and idealized piety, that was only to be shattered by modernity, no longer holds.”

In welcoming the audience to the lecture, Joseph M. McShane, SJ, president of Fordham, paused to remember the victims of weekend violence in Paris. He said the events inspired by religious differences placed the evening’s lecture in context, noting that Teter’s interfaith research is a step toward building “bridges of understanding.”

“Here at Fordham we . . . celebrate the human spirit, we seek to devote ourselves to the idea that life, not death, comes from faith in God,” he said.

“This is very important, especially in the aftermath of what happened in Paris.”

]]>On Nov. 10 and 11, Patrick Ryan, SJ, the Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society, made that brief document the focus of his fall McGinley lecture.

The document, 1,152 words in length, dedicated 433 words to the Jewish faith but only 133 words to Islam.

“Each section deserves careful analysis; each has a pre-history as well as a post-history with which we are living to the present day,” he said.

Father Ryan said some of the document’s pre-history included a tradition of anti-Semitic bias among Christians that cried out for “authoritative rejection” by the Church.

Father Ryan noted that one passage, in particular, repeated the early Church’s rejection of the teaching of the second-century heretic, Marcion of Sinope, who rejected everything that was Jewish in the Christian tradition. Paraphrasing St. Paul’s teaching that reaffirms God’s continuing love for the Jews, Father Ryan showed how the Council document rejects centuries of anti-Jewish hatred.

“[B]ut as regards election [the Jews]are beloved, for the sake of their ancestors; for the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable,” Father Ryan quoted from St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans.

“Nineteen centuries of Gentile-Christian hatred of the Jews as enemies of Jesus, himself a Jew, are here clearly renounced,” he said.

Father Ryan noted that the document’s short section on Muslims is not as detailed as the section about Jews. However, even the statement that the Church “regards Muslims with esteem” is an about-face in Church attitudes, very different from a prayer composed by the papacy just four decades earlier that asked God to “illuminate the minds of those still involved in the darkness of idolatry or of Islamism.”

“The document recognizes the centrality of Abraham to the faith of the Muslims,” he said, but it also acknowledges the long history of tension between Christians and Muslims that reached its apex during the Crusades.

“Nostra aetate, brief as it is, and especially its section on Muslims, marks a starting point for the process of dialogue between Christians and Muslims—perhaps even among Jews, Christians, and Muslims—that must be continued today and tomorrow for the sake of humankind and for the glory of God.”

The McGinley Lecture was followed with responses from Jewish and Muslim perspectives. This year’s Jewish response came from Magda Teter, PhD, the recently appointed Shvidler Professor of Judaic Studies.

Teter said the document represents both tradition and change in a complex way, and should be defined more by what followed it than by its actual content. It became a springboard for new dialogue between Jews and Christians. Still, she said the conciliatory voice was charged with facing down centuries of blame for the death of Christ.

“Jews lived this curse around the world,” she said.

Professor Hussein Rashid, PhD, a faculty member from Hofstra University, shared the Muslim point of view. He said that while Nostra aetate certainly spurred new conversations, it was burdened by a cultural memory that carries hope alongside stigma.

Rashid said he found hope in Pope Francis’ recent visit to the 9/11 memorial, where he said the stigma of the “cultural memory that Muslims are the violent Other” still lingers.

“Yet in listening to the words of Pope Francis spoken there, we understand that he saw the location as a transforming space in our relationship with each other,” said Rashid.

“It is in Pope Francis that we see the embodiment of Nostra aetate . . . the rejection of the worst in us and a commitment to the best in us, inspired by the vision of a more peaceful society, [and]the transformation through acts and a deep listening to each other that is our challenge for the next 50 years.”

]]>“You can’t escape noticing the absence of the former presence,” she said.

On Nov. 16, Teter will assume the newly endowed Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies at a ceremony at the Lincoln Center campus. The chair, housed in the Department of History, was created with a $3 million gift from Eugene Shvidler, GABELLI ’92.

At the installation, Teter will deliver a lecture, “Alienation to Integration: Rethinking Jewish History,” to which she will bring an intimate awareness of preserving knowledge inspired, in part, by her father. She said one of the things her father witnessed as a young child was the liquidation of the Jewish ghetto in his town. Later, he wandered into an abandoned synagogue and found sacred scrolls strewn about the floor.

“I don’t know how a five- or six-year-old child responds to that,” she said.

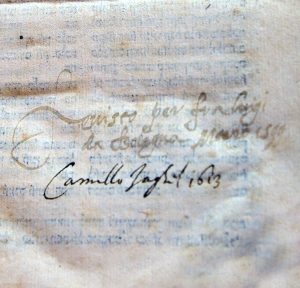

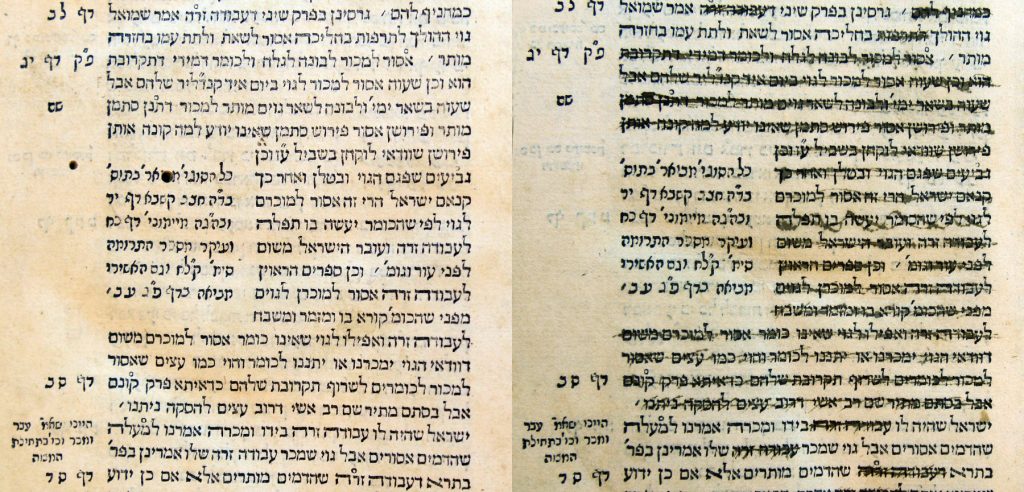

Teter has begun to assemble a new collection of rare Hebrew scrolls and books that will be housed at Fordham Libraries and used by students taking her courses.

“This is a tremendous acquisition,” said Linda LoSchiavo, director of Fordham Libraries. “The items will be incorporated into our special collections and we’ll be able to use them for exhibits.”

An important aspect of the collection is its usability, said Teter. While the books are valuable and rare, many are second and third editions, rather than first—chosen because Teter wants her digital-focused students to handle and use the old texts.

“My students are always shocked when I bring a 500-year-old book to class,” she said. “They’ve never touched something that old.”

While she applauded the accessibility afforded by digitalization, she said that scale is often lost in reproduction—to say nothing of the feel.

“On the screen everything is the same size, the physicality gets lost,” she said. “It’s important for this generation to feel where the font pressed against the page, to understand that every single letter was once a physical object that had been put there by someone, backwards and upside-down, and then pressed [to create an image].”

Teter said that it is fortuitous that the Shvidler chair has been established 50 years after Nostra aetate, the Vatican II declaration that changed the course of church relations with Jews by encouraging the study of Hebrew texts for mutual understanding.

“Jewish studies is extremely important for understanding the history of Christianity, especially Catholicism,” she said. “Teaching Jewish studies here will illuminate aspects of the Catholic history in ways that would not have been illuminated without thinking of Jews as being part of that mutual history.”

But not all of that history between Judaism and Catholicism is easy, she said. Church laws required Jews to bring their books to the church to be licensed—and sometimes the books were censored. Teter has purchased two copies of the same book published in Venice in 1547, one of which is expurgated and the other is not. Placed side-by-side, researchers can determine which content was blacked out.

“Anything that they found offensive or dangerous to the church they censored, expurgated, or banned,” said Teter.

“People who get exposed to this will see the sting of censorship in its raw form,” said Stephen Freedman, PhD, provost of the University. “This exposure will get students to think about the differences, and that is extremely important.”

Freedman said that the interreligious dialogue fits into the larger ecumenical context of the University. He said that the McGinley lecture series by Patrick Ryan, SJ, McGinley Professor of Religion and Science, has created an ongoing dialogue between Muslims, Jews, and Christians. And Fordham’s Orthodox Christian Studies Center’s Solon and Marianna Patterson Triennial Conference on Orthodox/Catholic Dialogue fosters a conversation between Catholics and Orthodox Christians.

“By exploring similarities and differences, you respect them,” he said.

Beginning on Nov. 16 the original books will be on display on the 4th floor of the Walsh Library, in O’Hare Special Collections, Mon. through Fri. 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Quinn Library at Lincoln Center will have a similar exhibit using photographs of the originals.

]]>