|

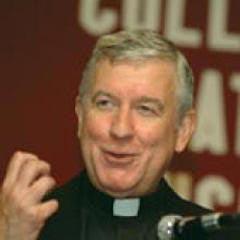

Father McShane served as the 32nd president of Fordham from 2003 to 2022. At the awards banquet, he was given the 2024 Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, Award, named in honor of an American priest and civil rights advocate who earned the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Medal of Freedom.

In a tribute video played at the ceremony, Father McShane thanked his colleagues for their service and dedication to their collective work.

“I want to shine the spotlight on you: the scores of women and men religious and the hundreds of talented devoted laywomen and laymen who have led and continue to lead our member institutions with discerning wisdom, deep love, and great effectiveness,” he said. “You keep our sacred and noble mission alive.”

“He was like another dad to me. He befriended, loved, kept up with, and supported me,” said Catherine McGovern, FCRH ’81, echoing the sentiments of alumni of many generations.

Father Daly served as director of Campus Ministry at Fordham from 1980 to 1987. Later, he became assistant alumni chaplain, providing pastoral support to Fordham’s global community of more than 200,000 alumni from 2015 to 2019. This included attending alumni receptions and retreats, as well as writing seasonal prayers to alumni, often with a personal and poignant touch. He also served as chaplain to the women’s basketball team from 2017 to 2019, earning recognition from Fordham Athletics for his work. (Fun fact: His old Campus Ministry office served as the office of the fictional Father Damien Karras in the movie The Exorcist, said Beth Tarpey Evans, FCRH ’84, who once worked in Father Daly’s office. “He was so proud of that! He left that nameplate on the door,” Evans said.)

A Second Father

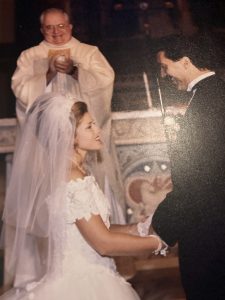

What alumni remember most about Father Daly is the way he cared for them in the same spirit as a father, comforting them during difficult times and rejoicing with them during the most important moments of their lives, said those who knew him. He was a gregarious, fun, witty, and kind priest who took great pride in their accomplishments, said McGovern, who is part of a circle of women that fondly refer to themselves as “Leo’s Ladies.”

He traveled across the country, marrying, baptizing, and blessing thousands of people—sometimes multiple generations in a single family, said his niece, Elizabeth Shortal Aptilon, FCLC ’85, GABELLI ’90.

“You don’t meet that many people who are genuinely good people. There aren’t that many people that stay in touch with you for decades. But my uncle was someone who really maintained lifelong friends,” said Aptilon.

An Advocate at Home and Abroad

Father Daly was born on July 29, 1930, in Brooklyn, New York, to Joseph Daly, a salesman, and Margaret McGowan Daly, a homemaker, both of whom had Irish heritage. He graduated from Brooklyn Preparatory High School, a Jesuit school in his home borough. He went on to earn a Master of Arts degree from Fordham’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and a degree in counseling psychology from Columbia University.

Father Daly entered the Society of Jesus in 1948 and was ordained a priest at the Fordham University Church in 1961. He served his fellow New Yorkers in many roles, including assistant principal at St. Peter’s Prep in Jersey City; administrator at Loyola Seminary in Shrub Oak, New York; high school counselor at Regis High School and Xavier High School in Manhattan; community superior at Xavier High School; and assistant to the rector of the Jesuit community at St. Peter’s College in Jersey City. He conducted retreat work as a staff member and director at St. Ignatius Retreat House on Long Island before it closed in 2012. Father Daly also served communities abroad, as campus minister at the University of Guam and as a chaplain at a U.S. Army missile range in the Marshall Islands.

Father Daly was a great storyteller who treasured time with family and friends, said his niece. In his spare time, he loved listening to jazz music and playing golf, she said.

His friend and former colleague Daniel J. Gatti, S.J, who used to serve as Fordham’s alumni chaplain, recalled the time Father Daly nearly made a 165-yard hole in a single shot—and almost won a free car in the process.

“Leo was about eight inches [away],” said Father Gatti, who had attended a Fordham Gridiron Golf Outing with Father Daly and two other Jesuits. “The whole day, no one won the car. … But Leo, I think, was the closest,” he said, chuckling.

‘He Served God’s People Well’

Four years ago, he was diagnosed with a parotid gland tumor, said McGovern, an OB-GYN whom Father Daly jokingly called his “personal obstetrician.” Despite dealing with serious illness during his final years—surgeries, radiation, immunotherapy, and partial loss of vision and hearing—Father Daly remained cheerful and involved with his Jesuit community and those he loved, said those who knew him.

“Throughout his long life, he served God’s people well,” Father Gatti said.

Father Daly is survived by his niece; grandnephew Brandon Craig Aptilon, GABELLI ’22; grandnephew Bradley Edward Aptilon; and nephew, James P. Shortal, his wife, Denise, and their daughter, Kristin. He is predeceased by his sister, Helen Shortal, née Daly, GSE ’49. His wake will be held at Murray-Weigel Hall on Jan. 19 from 3 to 8 p.m. The funeral Mass will be held the next day at the University Church at 11 a.m. and livestreamed on Campus Ministry’s website. Father Daly will be buried at the Jesuit Cemetery in Auriesville, New York. Gifts in his name may be made to the Leo Daly, S.J., Scholarship Fund.

“There is no conflict between science and religious belief,” he once told a television interviewer. “My faith is enriched by my science, and my science enriches my faith.”

Father Coyne rejected the view that science is the only way to true and certain knowledge, but he also challenged religious fundamentalists and proponents of the intelligent design movement, which he said reduces God to a “dictator God … who made the universe as a watch that ticks along regularly.”

In 2005, he published an essay, “God’s Chance Creation,” in the Catholic magazine The Tablet in response to a New York Times op-ed by Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, a prominent proponent of intelligent design.

“God in his infinite freedom continuously creates a world that reflects that freedom at all levels of the evolutionary process to greater and greater complexity,” Father Coyne countered. In an evolutionary universe, he wrote, God, like a loving parent, “is not continually intervening, but rather allows, participates, loves.”

Similarly, he challenged his friend Stephen Hawking, the Cambridge University physicist who wrote in A Brief History of Time that when scientists finally come to understand the formation of the universe, “it would be the ultimate triumph of human reason—for then we would know the mind of God.”

Father Coyne described Hawking’s concept of God as “something we need to explain parts of the universe we don’t understand. I tell him, ‘Stephen, I’m sorry, but God is a God of love. He’s not a being I haul in to explain things when I can’t explain them myself.”

George V. Coyne was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1933. After attending Loyola Blakefield, a Jesuit high school in Towson, Maryland, he entered the Society of Jesus in 1951. “They threw out the fishing net,” he once joked, “and I didn’t know any better.”

At the Jesuit novitiate in Wernersville, Pennsylvania, a professor of ancient Greek and Latin literature helped turn him on to astronomy, providing him with books on the subject and a flashlight so he could read them in bed after lights out. “It was forbidden fruit,” Father Coyne told The Catholic Sun in 2012, “but it was good fruit!”

He continued his studies at Fordham, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and a licentiate in philosophy in 1957. Five years later, he earned a doctorate in astronomy at Georgetown, where he studied the chemical composition of the moon. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1965 and soon after that joined a team of researchers at the University of Arizona who were mapping the surface of the moon—something Jesuit scientists had been doing since the mid-17th century. Their research helped guide NASA as it planned the Ranger missions and Apollo crewed missions to the moon during the 1960s.

Father Coyne later focused his research on the life and death of stars, especially binary stars, and the evolution of protoplanetary discs, among other topics. He published more than 100 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals. In 2009, he received the George Van Biesbroeck Prize from the American Astronomical Society, and an asteroid—14429 Coyne—was named after him.

Brother Guy Consolmagno, S.J., the current director of the Vatican Observatory and a former Loyola Chair in Physics and Astronomy at Fordham University, was a graduate student at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Lab in the 1970s when he first met Father Coyne. They later worked together at the Vatican Observatory.

“His instructions to each of us upon arriving at the observatory [were] simply: ‘Do good science,’” Consolmagno said at the funeral Mass for Father Coyne, held on Feb. 17 at LeMoyne College. “The science itself was the goal. And he gave us the space to make it happen.”

Under Father Coyne’s leadership, the Vatican Observatory expanded from its traditional base at Castel Gandolfo south of Rome to a second site on Mount Graham in Arizona, where in the early 1990s he presided over the installation of the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope, or VATT. He founded the Vatican Observatory Summer School, a research academy for graduate students, creating opportunities for women to become affiliated with the observatory research staff for the first time.

From 2006 to 2011, he served as president of the Vatican Observatory Foundation, and for the past eight years he held the McDevitt chairs in religious philosophy and physics at LeMoyne College, where he taught courses in astronomy, cosmology, and the relationship between science and religion.

Father Coyne often described parallels between science and religion while maintaining that they are independent pursuits. The Bible, he often noted, predates modern science, which he saw as neutral, a discipline that doesn’t have theistic of atheistic implications in itself.

In a 2010, Father Coyne and Consolmagno were interviewed by Krista Tippett, host of the NPR show On Being. Father Coyne spoke about the temptation to imagine a “God of the gaps.”

“We tend to want to bring in God as a God of explanation, a God of the gaps. … Newton did it,” he said. “If we’re religious believers, we’re constantly tempted to do that. And every time we do it, we’re diminishing God and we’re diminishing science. Every time we do it.”

He said that his belief in God and his scientific knowledge led him to consider, “What kind of God would make a universe like this?”

“I marvel at this magnificent God,” Father Coyne said. “He made a universe that I know as a scientist that has a dynamism to it, it has a future that’s not completely determined. … This is a magnificent feature of the universe.”

“My knowledge of the life and death of stars,” he added, “leads me also to know that there’s a unity, a whole universe with respect to life and death. If stars were not being born and dying, we would not be here. The sun is a third-generation star. It was only after three generations of stars that we had the chemical abundance to make an amoeba, to make primitive life forms, and through that to come to ourselves.”

He said his religious faith, like science, is something that he worked at constantly.

“Every morning I wake up, I have my doubts, I have my uncertainties, I have to struggle to help my faith grow, because faith is love,” he said, and “love in marriage, love with friends and brothers and sisters is not something that’s there once and for all, and always kind a rock that gives us support. And so what I want to say is ignorance in doing science creates the excitement in doing science, and anyone who does it knows that discoveries lead to a further ignorance.”

Ultimately, he said, “Doing science to me is a search for God, and I’ll never have the final answers, because the universe participates in the mystery of God. If we knew it all, I’d sit under a palm tree with my gin and tonic and just let the world go by.”

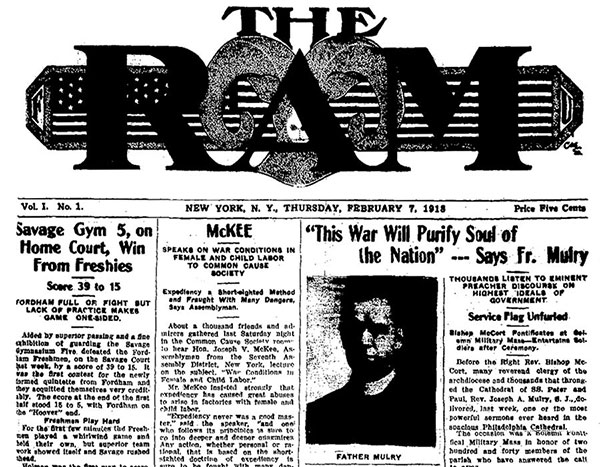

]]>Ringing the room were enlargements of front pages. They conveyed the scope of events covered by the paper across the decades: world wars, McCarthyism, civil rights, student protests, Watergate, 9/11, and more.

Then there was the front page of the very first issue of The Ram, published on February 7, 1918. The layout is crisp and the tone is serious. Alas, the viewpoint expressed by the lead headline reveals the perils of composing first drafts of history. It quotes Joseph A. Mulry, S.J., then president of Fordham, who had a reputation for fiery sermons on patriotic themes: “This War Will Purify Soul of the Nation.”

Father Mulry was referring to World War I, then deep into its fourth year, which was time enough to have figured out that rather than a rite of purification, the stalemate in Europe was more like mindlessly mechanized slaughter, an exercise in futility and stupidity. With hindsight we might forgive Father Mulry, especially given that his underlying thesis was that “no part of the body politic shall oppress another.”

Practicing the Discipline of Verification

The Ram‘s first editors were trying to speak to a cause then vital to Fordham students, some hundreds of whom were serving on or near the front and whose need for news from campus was the reason for founding a weekly in the first place. (That’s right, The Ram began as a chronicle for troops overseas of academic doings in the rural northeast Bronx.) But as any journalist will tell you, it’s often difficult to interpret events in the midst of their unfolding.

“If you’re a news reporter, you need to hope for humility,” said former Ram editor-in-chief Jim Dwyer, FCRH ’79, to more than 100 guests at the paper’s centennial dinner. “And own your own mistakes.”

Dwyer is a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and a columnist for The New York Times who has written on everything from the Byzantine machinations of the MTA to improving care for HIV-positive pregnant women. If anyone could get away with tossing bouquets of self-congratulation, it’d be this guy on this night. Instead he extolled “the journalism of verification, where you can see the structures that hold up the stories, where sources are named and facts are corroborated.”

Journalists have a phrase for such high standards: a pain in the rear. But insofar as journalists practice them, even revere them, it’s because they came across someone early on who insisted they be followed in their novice attempts at editing and reporting—or in managing a newspaper, as slapstick and earnest an enterprise as humans have devised. For the people in Bepler Commons, that formative education would’ve occurred while scrambling on deadline to put out The Ram.

Dwyer also name-checked his former professor and long-time mentor, Ray Schroth, S.J. Beginning in the late 1960s, Father Schroth taught journalism at Fordham and other Jesuit colleges for almost 50 years. A kind of anti-Mulry, Father Schroth instructed students to question official statements from powerful people in justification of their actions—on issues ranging from potholes to low-level weed arrests to war. Not that these explanations are always wrong, just that they need to be checked.

One way journalists do this is by examining a policy’s concrete effect on the lives of non-powerful people, and then amplifying the voices of these people in the press—after checking their claims, too.

Calling Out Untruths, Winning Trust

That was a theme of the speech by Louis D. Boccardi, FCRH ’58. He’s a Ram alumnus and former president and CEO of the Associated Press, the world’s largest news organization. Boccardi started his career when newsrooms racketed with the sound of manual typewriters and ended it by transitioning AP into the internet age.

“’Fairness and accuracy’ is a piety, but it’s the start of what we do,” he said. “And when we find an untruth, we should label it clearly so. In the end, our only claim on the reader’s or viewer’s attention, and on their support for what we do, is that they trust what we say.”

The value of telling the truth against all obstacles was another theme of the night. Solid reporting requires familiarity with the methods of pursuing truth. That’s where The Ram and its equivalents come in. Students sign up to practice the full menu of journalistic skills, from rapid fact-gathering to investigative techniques. Students then put their stories out into the world, where sometimes they stand up to scrutiny and sometimes they don’t. Either way, lessons learned.

The result can be high honors. Besides Jim Dwyer, two other Ram editors went on to earn a Pulitzer Prize: Arthur Daley, FCRH ’26, for sports reporting at The Times, and Loretta Tofani, FCRH ’75, for her Washington Post series “Rape in the County Jail.” Tofani was one of the first women to serve as editor-in-chief of The Ram. Many women have since followed her in the role.

The latest is Theresa Schliep, a 21-year-old Fordham senior and editor of The Ram’s 100th edition. Schliep presides over more than a physical newspaper. She manages a multimedia platform that, more often than not, lives up to the standard of pain-in the-rear reporting.

When asked why she goes to the trouble, she says, “It’s our right as Americans, and as people, to say what we want to say—factually and accurately.”

There it is: evidence that a new generation has submitted to the practice of digging up and offering the journalistic truth, of winning trust through verification, corroboration, and clear prose. In closing, a benediction: May they prosper as they make their mistakes and publicly correct them, and as they doggedly call the powerful to account. It’s an especially hostile time to aspire to be a journalist. God bless those who would do it.

—Jim O’Grady, FCRH ’82, a former Ram reporter and editor, is a features reporter at WNYC.

UPDATE: In December and January, several New York elected officials—from Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz Jr. and Mayor Bill de Blasio to Governor Andrew Cuomo (FCRH ’79), U.S. Rep. José E. Serrano, and Senators Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand—saluted The Ram on its 100th anniversary. Congressman Serrano’s message was published in the Congressional Record on December 20.

[doptg id=”134″]Note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Loretta Tofani as the first woman to serve as editor-in-chief of The Ram. She was preceded by Mary Anne Leonard, TMC ’70, who achieved that distinction in 1969.

]]>“It was not meant to be,” said Simpson, a 1970 graduate of Fordham College at Rose Hill.

Since then, however, he’s found his way to another role in the space race, an earthbound occupation with responsibilities that show just how complex—and potentially fraught—the exploration of the final frontier has become since his youth.

As executive director of the Colorado-based Secure World Foundation for the past seven years, he has worked with all the governments and private companies that have joined the space age since the days when the U.S. and the Soviet Union were the only two players. The foundation works for peaceful, sustainable use of outer space, taking on a whole universe of concerns as well as opportunities.

After retiring from the foundation on Oct. 1, he plans to stay engaged with the space-related initiatives it has helped advance around the world. “People are beginning to realize that there’s some real down-to-earth impact, for better and for worse, from space technology, and that’s the future,” he said.

A Career Launches

Simpson was interested in science from an early age, and edited a science newspaper as a student at Edgemont High School in Westchester County, New York. As an honors student at Fordham, he took to political science, an interest that was fueled when political science chairman James C. Finlay, S.J.—later president of Fordham—got him an internship at the New York state constitutional convention in 1967.

“How he pulled that off, I don’t know,” Simpson said. “It was mostly graduate students and seniors, and there I am, a rising sophomore, trying to figure things out.”

He later earned several advanced degrees, including a doctorate from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, and embarked on an academic career, serving as president of Utica College, the American University of Paris, and the International Space University in France before joining the Secure World Foundation in 2011.

The foundation has offices in Broomfield, Colorado, and Washington, D.C. It was established in 2002 with philanthropic funding from husband-and-wife entrepreneurs Marcel Arsenault and Cynda Collins Arsenault to bring governments, industry, and various organizations together on potentially fractious space-related issues.

One of these issues is space junk. As unbelievable as it may seem, the vastness just beyond Earth is growing crowded. “We’re at the point where we can’t any longer just sit back and say, ‘Hey, space is big, go do what you want to, you’ll be OK,’” Simpson said.

There are probably 2,000 defunct spacecraft in orbit, along with about 20,000 pieces of detectable debris—the size of a softball or bigger—because of accidents like the collision between a derelict Soviet-era satellite and a privately launched American communications satellite in 2009, Simpson said. “There may be a million pieces that are smaller than a golf ball,” he said. “Maybe pretty soon, we’re going to need a system for traffic management in space” because debris is both dangerous and hard to manage, he said.

“On Earth, we can clean up a mess because it stays in one place. In orbit, it doesn’t stay in one place. It moves, and it’s moving at 17,500 miles per hour,” he said.

Setting up a system for governments to track and mitigate the problem of debris is part of the foundation’s work with the U.N. Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. “There’s still a fair amount of trust-building that has to go on to get people to agree that this is not world government trying to take away their chance to be involved in an exciting industry,” Simpson said.

The foundation offers nonaligned expertise that can help nations work through space security issues, said Asif Siddiqi, Ph.D., a Fordham space historian who has worked with the foundation. “I think what they’re providing is a kind of nongovernmental, noncorporate perspective on space security, which is really important, and they have really good people working there who are experts in their particular fields,” he said.

The foundation’s work intersects with military issues at times, as shown by a 2017 initiative to promote greater public study of the weapons that nations are developing to disrupt or destroy satellites and other space technologies.

“Space is not the sole domain of militaries and intelligence services,” the foundation said in a statement. “Our global society and economy is increasingly dependent on space capabilities, and a future conflict in space could have massive, long-term negative repercussions that are felt here on Earth.”

Responding to Incoming Threats

Other security issues relate to incoming asteroids, and not just because of the damage they could cause, Simpson said. He noted that an asteroid burst over the Mediterranean in 2002 with the force of a nuclear bomb; if it had arrived a few hours earlier, it could have burst over the border between India and Pakistan during a military standoff between the two nuclear-armed rivals, he said. “I’m not sure that people would have been rational enough to say, ‘This wasn’t a nuclear weapon,’” Simpson said.

Since then, the foundation helped establish the International Asteroid Warning Network to help prevent such mistakes, and also has its eye on other potentially dangerous scenarios—such as, for instance, one nation intimidating and alarming other nations to the point of crisis by firing a nuclear weapon at an incoming rock.

The foundation works through the U.N. to try to set guidelines for nations’ responses and has brought experts together to talk about how to alert the public to a threat without sparking panic, Simpson said. The foundation’s Broomfield Hazard Scale provides a uniform guide for the threat posed by an asteroid.

“Governance, in effect, is the key thread that I think ties together a lot of our work,” Simpson said. For instance, he said, “if there were no plan for dealing with car accidents, there would probably be a lot more fights around [them]. Most folks, at least, don’t reach in the glove box for a firearm, we reach in for a document. We have a process, know what we’re supposed to do, don’t have to invent it after a challenge occurs. That’s what we’re trying to do with space.”

The foundation works on a wide portfolio of issues, including—recently—an effort to come up with basic rules covering the mining of asteroids and near-Earth objects, Simpson said. In early 2018, he went to the Vatican Observatory for meetings about how to link the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals to Space 2030, the emerging global agenda for space activity.

Boundless Opportunities

Space activity remains Simpson’s passion not so much for the science but for its impact on people, an outlook rooted in his political science studies at Fordham—“politics has rules, but people are at the core,” as he put it.

He noted that space has fostered medical advances; the weightlessness of space has shed light on the role of weight-bearing exercise in staving off osteoporosis, he said. Developing nations have used GPS satellites to synchronize their cell towers, expanding cell service without having to set up their own synchronization systems. And crop disease can be detected from satellites, thanks to spectrographic technology that can spot color changes associated with blight.

In other words, all the security worries surrounding space technology are mixed with new possibilities for improving life on Earth.

“It’s mind-boggling. You’d think that the time would come when you cease being amazed by what people are doing,” he said. “[I] really enjoy not only having entered the space sector but the opportunity to continue to work with it, because it just keeps solving problems for people.”

After stepping down as executive director of the foundation, he’ll keep working with various groups devoted to space-related issues. His first stop will be the 69th International Astronautical Congress in Bremen, Germany, where he’ll present a paper on the role of NGOs in the development of international space policy. “Life shows no signs of slowing down,” he said.

]]>

Known for integrating prayer with art, Father Gilroy believed that spirituality could be manifested through creative practices like painting. He launched the website, Prayer Windows, more than a decade ago to offer guidance on how to encounter God through the arts.

“Through art, we co-create with God,” he wrote in an article published in the National Christian Life Community of United States’ Harvest magazine in 2000.

Most recently, Father Gilroy, who lived at an infirmary at Murray-Weigel Hall, worked with Campus Ministry to offer spiritual direction. He led retreats and talks focused on art and spirituality at the Westchester campus, where he also had a part-time art studio.

“These [retreats] were well-received by participants,” said José Luis Salazar, S.J., executive director of Campus Ministry.

Before his death, Father Gilroy was slated to do a number of lunchtime talks on Ignatian spirituality and art at the University, as well as an art and yoga retreat in December at the Goshen Center.

Carol Gibney, associate director of Campus Ministry and for spiritual and pastoral ministry at Rose Hill, worked with Father Gilroy on a Lenten art and yoga retreat this past March.

“He was really gifted at sharing his love and passion for art, and using art as a portal into the sacred to allow us to pause and reflect,” she said.

Though Father Gilroy, who struggled with diabetes, was new to Fordham, Gibney said his energy was magnetic—as was his cheerful laugh.

“He laughed with his whole body,” she said. “It was really joyful. He had what I desired for others and myself—an interior freedom. He allowed God’s light to shine through him.”

In a Facebook post, James Martin, S.J., acclaimed author and editor at large at America magazine, described Father Gilroy as “an amazing friend and Jesuit brother” who was “supportive, interested, generous, thoughtful, caring, funny, wise, and challenging when he needed to be.”

“I’ll miss that irrepressible laugh; I’ll miss his wisdom; I’ll miss his art; I’ll miss his counsel; I’ll miss his gentle presence in the world,” he wrote.

]]>

Horrors of War: From Goya to Nachtwey showcases the classic work of 18th-century painter Francisco de Goya y Lucientes aside modern-day photographer James Nachtwey. The work will be on display in in Canisius Hall through the end of the fall semester.

“In these photographs and in the face of isolation, there is presence and compassion,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “That is what the institute is about.”

Nachtwey said he was honored to place his photographs alongside the work of the painter Goya, who he called the “first war photographer.” Together, the works highlight both the darkness and the hope found in the tragedies of war.

Goya’s work is from his Los desastres de la guerra [The Disasters of War] series. The series consists of 82 prints created between 1810 and 1820 showcasing the conflict between Spain and France. Seventeen out of the 82 prints were reproduced from originals that are held in The Hispanic Society Museum and Library.

Nachtwey’s work captures scenes through the eyes of humanitarian crisis workers and their subjects. Among the images in Horrors of War are a mother clutching her child amidst a debris-strewn landscape; a young woman lying in a hospital bed; and a man, who’d lost a leg in conflict, attempting to mount a surfboard.

“These are not easy to look at and yet difficult to look away from,” said IIHA Executive Director Brendan Cahill.

“A lot of times humanitarian workers are unable to process what they see on a daily basis, so these images bring their reality to life for someone who may never find themselves in that circumstance,” said Angela Wells, IIHA communications officer.

The exhibition is open Monday to Friday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

-Veronika Kero

]]>

Leonard Cassuto, Ph.D., professor of English and American Studies and author of The Graduate School Mess: What Caused It and How We Can Fix It (Harvard, 2015)

Leonard Cassuto, Ph.D., professor of English and American Studies and author of The Graduate School Mess: What Caused It and How We Can Fix It (Harvard, 2015)

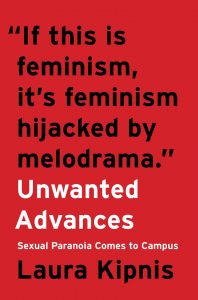

“At the top of my summer book stack is Laura Kipnis’ new book, Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to Campus (Harper, 2017). Kipnis’ investigation of the Title IX excesses on many American campuses has a personal side: When she wrote an article about a Title IX investigation at her own university, she found herself the subject of an investigation, too–and that inquiry helped to inspire this book. This is a book about current events, indeed.”

Bill Baker, Ph.D., director of the Bernard L. Schwartz Center for Media, Public Policy, and Education

Bill Baker, Ph.D., director of the Bernard L. Schwartz Center for Media, Public Policy, and Education

“My summer reading gets a double dip as I read sitting in the lantern room of a lighthouse we care for in Nova Scotia (Henry Island). This year I’ll be reading Enough Said (St. Martin’s Press, 2016) by Mark Thompson, the New York Times Company president and former BBC Director General. He has written a powerful book about what’s gone wrong with the language of politics. I’ll also be reading The Naked Now (The Crossroad Publishing Company, 2009) by Richard Rohr, a Franciscan friar who writes some of the most powerful meditative philosophy I’ve ever read. A lighthouse is a good place to read about God and the spiritual light.”

James McCartin, Ph.D., associate professor of theology

James McCartin, Ph.D., associate professor of theology

“As a father of three young kids, I’ve grown to appreciate books that offer a window into how children see the world–maybe in an effort to figure out my own kids. Therefore, my summer reading season begins with two childhood memoirs. The first is Maurice O’Sullivan’s Twenty Years a-Growing (J.S. Sanders Books, 1998), set on a remote island in the southwest of Ireland a century ago, and the second will be Carlos Eire’s Waiting for Snow in Havana (Free Press, 2004) which narrates his story as an immigrant growing up between Cuba and the United States in the 1960s. Then, I’ll pick up a book I started last summer but put down as the school year began, Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. As to Dostoyevsky, I’ve long been embarrassed to say that I’ve never read him, so now’s my chance to put the embarrassment behind me.”

Heather Dubrow, Ph.D., John D. Boyd, S.J. Chair in Poetic Imagination and the director of Poets Out Loud

Heather Dubrow, Ph.D., John D. Boyd, S.J. Chair in Poetic Imagination and the director of Poets Out Loud

“A growing pile of books in my field has been staring at me balefully from my night table for some time, and before they topple over I hope particularly to read more sections of two of them that I have dipped into only briefly before: Brian Cummings’ The Literary Culture of the Reformation (Oxford, 2002) and Reuben Brower’s Fields of Light (Greenwood Press, 1980). I am in the middle of an extraordinary magical realist novel, George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo (Random House, 2017), as well as some volumes of poetry, such as Alicia Ostriker’s latest, Waiting for the Light (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017).

Christina M. Greer, Ph.D., associate professor and associate chair of the political science department

Christina M. Greer, Ph.D., associate professor and associate chair of the political science department

“Since I am preparing to write a lot this summer, I tend to read fiction to help me ‘hear’ language better. Right now I am finishing a series of short stories by Mia Alvar, In the Country (Oneworld Publications, 2016) about Filipino migrations and relationships. I plan on finishing Luther Campbell’s’ memoir The Book of Luke: My Fight for Truth, Justice, and Liberty City (HarperCollins, 2015) about Liberty City, Miami, Florida. He’s a controversial figure, but his analysis of residential racism and segregation in Miami is fascinating. I am also going to read Underground Airlines (Random House, 2016) by Ben Winters, an alternative history of life in the U.S. had the Civil War never happened. [And] since I am teaching Congress in the fall, I’ll likely begin rereading Robert Caro’s Master of the Senate (Vintage Books, 2003), about my favorite president and brilliant congressman, LBJ.”

Barbara Mundy, Ph.D., professor of art history

Barbara Mundy, Ph.D., professor of art history

“My summer reading list is heavy with books on cities, a topic I’ve written a lot about. At the top is Jennifer Egan’s Manhattan Beach (Simon & Schuster, 2017), a novel set in New York in the 1940s, and I’m getting ready to devour it as soon as I get through my end-of-year reports. David Lida is a Mexico-City-based writer; I can dip into his book of short essays, Las llaves de la ciudad (Sexto Piso, 2008) [Keys to the City], whenever I need to be transported to one of my favorite cities in the world. And then there’s Small Spaces, Beautiful Kitchens (Rockport Publishers, 2003) by Tara McLellan; I’m downsizing to an apartment and trying to figure out how to cram all my cooking gear (fermentation is much on my mind) into a smaller space.”

Robert Grimes, S.J., dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center

Robert Grimes, S.J., dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center

“The number one book on my summer reading list is Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved By Beauty (Scriber, 2017), by Dorothy Day’s granddaughter Kate Hennessy. When I was a high school student at Xavier, we sometimes went to the Catholic Worker House on the Lower East Side, and I had the honor to meet Dorothy Day a couple of times. When Kate Hennessy spoke at the Fordham Rose Hill campus this year, I was unable to attend, so I’ll make up for missing that event with reading her book.”

Laura Wernick, Ph.D., professor of social work in the Graduate School of Social Service

Laura Wernick, Ph.D., professor of social work in the Graduate School of Social Service

“Given our political climate and the rise of the alt-right, coupled with ongoing investigations and hearings surrounding Russia and Donald Trump’s campaign, my reading list is focused upon understanding this context and history. Having just read Dark Money and Trump Revealed (Doubleday, 2016), my summer reading list has included All the President’s Men (Pocket Books, 2005) and The Final Days (Simon & Schuster, 2005), along with Masha Gessen’s The Man Without a Face (Riverhead Books, 2012), a critical read to understand the rise and power of Putin. I plan on following this with a series of edited volumes about hope and moving forward from the resistance movement.”

Mary Beth Werdel, Ph.D., associate professor of pastoral counseling and director of the Pastoral Care and Counseling program at the Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education

Mary Beth Werdel, Ph.D., associate professor of pastoral counseling and director of the Pastoral Care and Counseling program at the Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education

“I will be reading The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015) by Bessel van der Kolk. The book examines holistic approaches to trauma work. I’m interested in the way that spirituality relates to stress related growth, which is the examination of positive psychological consequences of moving through stress. I have a book contract related to the topic. This book touches on related themes of trauma and whole body healing.”

–Veronika Kero

]]>

Donna Rapaccioli, Ph.D., dean of the Gabelli School (GABELLI), recalled gestures both large and small that helped her develop personally and professionally. Her grandmother, she said, always reserved a quiet space at her house for Rapaccioli to study, while cooking her nurturing meals.

“Her potato-and-egg omelets, Eggplant Rollatini, and Sunday gravy, which I ate all week, fueled my scholastic career,” she said.

When Rapaccioli was completing her dissertation and needed technical help on the computer, she said, her father, who never went to college, managed to find her a programmer—“and this was waaay before Google!”

The dean mentioned support and inspiration from two others: Associate Professor Frank Werner, Ph.D., one of her teachers, and the school’s benefactor Mario Gabelli, GABELLI ‘65, who often “peppered” her with questions, and took an interest in her career.

“If you’d told me 30 years ago that I’d have a billionaire mentor, I would have called you crazy,” she joked. “But he is a true supporter. Mario exemplifies giving back. And he reminds us that to envision the future, we must look to the contributions of young people.”

She encouraged the graduating class to “remember your helpers, aim high, and always be humble and kind.”

Class valedictorian John Witkowski recalled freshman orientation four years earlier, when he and his follow students were welcomed by Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. Father McShane, he said, told the students that they were the “smartest class to enter Fordham.” Witkowski said that the graduating class shouldn’t misconstrue the truth behind the remark.

The Smartest Class

“We shouldn’t have interpreted being called the ‘smartest class’ as an homage to our success—credit belongs to the classes who had come before us,” he said. “It was their work that transformed Fordham over the years and convinced us to enroll.”

He then congratulated his fellow classmates on contributing to the legacy, and welcomed the next “smartest class.”

The Alumna of the Year award went to Christine Lowney, GABELLI ’98, partner at Ernst & Young. Lowney said that even though commencement weekend was a time for looking forward, students should carve out time in their future to come back and contribute to the school’s legacy.

“You as alumni can now play an active role in supporting your alma mater; I would dare to say you have an obligation,” she said.

In addition to recognizing student achievements, the awards event also celebrated faculty contributions. The Dean’s Award for Teaching Excellence for full-time faculty went to Kevin Mirabile, D.P.S., clinical assistant professor; the Dean’s Award for Teaching Excellence for adjunct faculty went to Joe Lizza; the Faculty Cura Personalis Award went to Clarence Ball, clinical assistant professor; and the Faculty Magis Award went to Mario DiFiore, the assistant dean for seniors.

]]>“Why? Because we kicked them under the bus in 1863,” Cummings said, noting the year slavery ended. “Do we have a moral responsibility? Jesus Christ says so. Don’t you think so?”

Moreover, Cummings wants to know “What are [we]going to do about it?”

Cummings will be the keynote speaker at an April 1 symposium to be held at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus titled, “Slavery on the Cross: Catholics and the ‘Peculiar Institution,’ Praxis and Practice.” He said he will discuss the same question with academics and activists sitting on three separate panels.

Bentley Anderson, S.J., associate professor of history and associate chair of the Department of African and African American Studies, which is co-hosting the event, said that the keynote talk will be preceded by two morning panels that will contextualize the topic, and followed by an afternoon panel that will address its legacy.

“We’ve invited scholars who deal with questions of race and religion from the past and into the present,” he said. “And we’ll have folks from the New York region who are actually putting their faith into practice by addressing issues of systemic racism.”

For Cummings, addressing the legacy of racism has become the culmination of a life’s work. After earning a law degree from Loyola University New Orleans and practicing for several years, he purchased a sugar cane plantation near New Orleans as an investment. But as he began to delve into the plantation’s history, he said he was shocked by his own ignorance of the institution of slavery.

Today, the Whitney Plantation is the nation’s first museum fully dedicated to the history of slavery, said Cummings. The plantation now celebrates the strength of the men and women who toiled in its fields, and it displays a wide variety historic items relating to slavery.

An Irish Catholic who had a modest upbringing in New Orleans, Cummings said his own working class family has no direct lineage to slave owners. But he believes all Americans must contend with the legacy.

“We’re all recovering racists because we were raised in this place,” he said.

Father Anderson, who also grew up in New Orleans, said he met Cummings when he toured the plantation with his parents. The two began a discussion about the church’s history with slavery, in which Father Anderson said Cummings did indeed ask him “What are you going to do about it?”

The April 1 symposium evolved from that conversation, said Father Anderson.

“He challenged me on a faith level and academic level, and what I can do is bring people together to discuss, reflect, and act,” said Father Anderson.

Cummings said he struggles on a personal level with the moral conundrum of the church’s role in slavery. He hopes the symposium will raise consciousness among contemporary Americans that, although they may not bear the responsibility for slavery, they must take responsibility for its legacy.

“We have put slavery in the rearview mirror,” he said. “It was done on someone else’s watch—not so far back we can’t see it—but we have to look forward and find out what our obligation is to its descendants.”

The event will be held from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. at the Corrigan Conference Center.

Participants:

Thomas Murphy, S.J., Seattle University

M. Shawn Copeland, Ph.D., Boston College

Bryan Massingale, S.T.D., Fordham University

James O’Toole, Ph.D., Boston College

John Cummings, Whitney Plantation Museum

Albert Holtz, O.S.B., Newark Abbey – Newak, NJ

Gregory Chisholm, S.J., St. Charles Borromeo – Harlem, NY

Maurice Nutt, C.Ss.R., Xavier University of Louisiana Institute

Jeannine Hill Fletcher, Ph.D., Fordham University

Co-sponsored by: Theology Dept., Political Science Dept., Philosophy Dept., Communication and Media Studies, Curran Center for American Catholic Studies, The Jesuits of Fordham University.

]]>