As you undoubtably know, yesterday in a neighborhood supermarket in Buffalo, N.Y., an 18-year-old gunman shot 13 people, killing 10 of them. Eleven of his victims were Black. As you also probably know from the news reports that we have all received, the gunman responsible for yesterday’s carnage spent months meticulously planning his attack, and posted a racist manifesto online, the content of which makes it clear that white supremacist ideology was his motivation for the murders.

Sadly, yesterday’s heinous killings were part of an alarming and sickening pattern: Black people continue to be murdered because of the color of their skin. This pattern reminds us (as if we needed to be reminded yet again) that racism continues to find a home in America. (Another way of saying that is to point out that our national original sin (slavery) has not been eradicated.) As a priest, I am expected to say something to calm and reassure those who are afraid and in pain. I must confess, however, that I find it impossible to look a Black person in the eye and say either “be not afraid,” or “things will be different and better in the future” if, as happened in Buffalo yesterday, a person can be shot dead while doing something as common as shopping for groceries.

Since I lived and taught in Buffalo when I was a young Jesuit, I must tell you that I wish that I could be there today to stand with the members of the city’s Black community in this moment of unspeakable sadness and loss, but I can’t. Like you, I can only mourn with and pray for the Black community of Buffalo from a distance. I know that you join me in grieving for those who died in yesterday’s attack. I also know that you, too, weep for their families.

In the wake of yesterday’s carnage, I would like to say this to our Black students, faculty, and staff: you are loved. You belong here. You are wanted here. We will do everything in our power to keep you safe, and to show you (both by word and gesture) that you are beloved members of the Fordham family.

I would also like to ask all of the members of the Fordham family to be gentle with and supportive of one another as we all process this horrific incident.

I am praying for all of you today, and indeed for our nation.

Prayers and blessings,

Joseph M. McShane, S.J.

Community Resources

Counseling and Psychological Services

Lincoln Center

140 West 62nd Street, Room G-02

Phone: (212) 636-6225

Rose Hill

O’Hare Hall, Basement

Phone: (718) 817-3725

Campus Ministry

Rose Hill

Campus Center | CMCE Suite 215

441 E. Fordham Rd.

Bronx, NY 10458

Phone: (718) 817-4500

[email protected]

Lincoln Center

Lowenstein 217

New York, NY 10023

Phone: (212) 636-6267

[email protected]

University Health Services

[email protected]

Lincoln Center: (212) 636-7160

Rose Hill: (718) 817-4160

Any member of the campus community who needs help can also call Public Safety at (718) 817-2222: the phone is staffed 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

]]>Yip has explored the human relationship with ethnic identity in more than 50 peer-reviewed papers. Her research specifically focuses on ethnic identity development among underrepresented populations, the association between ethnic identity and psychological adjustment, and the impact of ethnic-specific and general stressors on people’s well-being. Her work on racial and ethnic identity was featured in a 2019 Fordham News Q&A.

]]> Kelly Schmidt, Ph.D., was disturbed by racism from a very young age.

Kelly Schmidt, Ph.D., was disturbed by racism from a very young age.

“I don’t quite remember where I had learned about prejudice and discrimination for the first time, but I didn’t understand it and I kept asking my mom, ‘Why do people treat people differently because of the way they look?’” she said, “And she couldn’t give me the answers.”

“What she did was, she kept supplying me with books, so I was reading biographies of Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth, and all kinds of people who have experienced prejudice and oppression and fought to overcome it. That really stuck with me.”

In April, Fordham’s Curran Center for American Catholic Studies chose Schmidt, a 2021 graduate of Loyola University, as the second winner of its New Scholars essay contest. For her paper “’Regulations for Our Black People’: Reconstructing the Experiences of Enslaved People in the United States through Jesuit Records” (International Symposium on Jesuit Studies, March 2021), Schmidt was awarded a $1,500 cash prize.

“It’s quite an honor for my work to be recognized in this way. It’s so important that this award is promoting new scholarship that focuses on underrepresented and marginalized groups in Catholic history,” said Schmidt, who is the research coordinator for the Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation Project, a joint initiative of the Society of Jesus and St. Louis University.

The research is in some ways the pinnacle of an academic career that began with the books her mother gave her. In high school, Schmidt worked as a volunteer and employee at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati and served as a community-engaged fellow at Xavier University as an undergraduate.

After completing her bachelor’s degree in history and classics, she knew she wanted to be a historian of slavery and African American history, and went on to earn a master’s degree and Ph.D. in public history. The Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation Project, which was created in 2016 as a way to explore the Jesuits’ connections to slavery, was a natural fit, she said.

“Knowing how much the Jesuits had shaped me, I knew I needed to understand more. I had to understand what enslaved people’s lives were like with the Jesuits, and how the Jesuits justified holding people in slavery in their religious context and their mission,” she said.

John Seitz, Ph.D., an associate professor of theology at Fordham, said what made Schmidt’s work stand out was the way she expanded the scope of sources to tell the story of enslaved people.

“The great thing about this work is not only that it exposes a world that we’ve had a very difficult time seeing through the historical record,” he said. “But it’s also such a meticulous and creative way of reading records [bills of sale, sacramental records, correspondence between Jesuits]that ostensibly don’t really have anything to do with what she’s interested in exploring, which is the lives of enslaved Catholics people.”

Seitz noted that Schmidt’s research is in keeping with a broader national reckoning.

“With the rest of the country, Jesuit institutions more broadly are having a movement when more and more people are agreeing that it’s time to come to terms more honestly and in a more transparent way with painful histories, including Jesuit ownership of slaves. Kelly’s work is remarkable in helping this effort,” he said.

“She provides a foundation for the kinds of work that needs to be done for reconciliation, healing, and reparation, which is a long road.”

In addition, he said that Schmidt exhibited a spirit of generosity in the paper by laying out a roadmap for future scholars who might want to replicate the research.

“She’s been through all these many, many layers of papers that are scattered and diffuse. She doesn’t just hide that; she talks about the process in this essay, and in talking about the process, she provides a great gift to her fellow scholars in the future who may want to do something similar, to recreate this hidden world,” he said.

For Schmidt, the process of researching the lives of those enslaved by Jesuits in the South and Midwest was both challenging and inspiring.

“I felt challenged in my faith, seeing exploitation that happened to people through the church, but then, as I learned more and more about the enslaved people I was studying, I was just continuously blown away by how resilient they were in their faith, and how even their enslavement to Catholic slaveholders didn’t stop them,” she said.

“They were so committed to their faith and using it to uplift themselves and push for the way things ought to be.”

The larger lesson, she said, is that all history is interconnected, and one can’t simply go to the archives and find one box labeled “slavery” and learn the full story of the past.

“We have to look far and wide to piece together the story, and we have to look past different dioceses and religious orders. Slavery wasn’t isolated to one institution, so you have to look through state records, local records,” she said.

“Doing it, we pieced together the lived experiences of enslaved people whose stories haven’t been told.”

]]>

Though a truce is in effect between Israel and Hamas, the conflict has provoked anti-Semitic and anti-Islamic attacks globally, including one in Times Square on Thursday, in which a Jewish man was beaten by protesters. He survived yet suffered injuries.

The victim, Joseph Borgen, said he was surprised at the level of hate against him, and said that there is a larger issue with hate against minorities in the city: “I have coworkers of Asian ethnicity who are afraid to go on the subway at night because you know, they are afraid they are going to get attacked on the subway. The amount of hate that is taking place these days is just mind-boggling to me. I mean, that shouldn’t happen to anyone in New York City.”

To which I say, it should not happen to anyone, anywhere, and especially not among the family of People of the Book. We owe our Jewish and Muslim cousins the same respect and love that we desire as Catholics. An attack against one of us is an attack against all of us, and violence inspired by anti-Semitism (as is apparently the case with Mr. Borgen), or because of any kind of racial or religious hatred, is especially appalling.

This weekend we pray for an enduring peace in the Middle East, and a cooling of ethnic and religious hatred here and around the world. I know you all join me in opposing the violent actions of mobs inspired by the current conflict in Israel and Gaza, and in working toward a world in which justice and understanding prevails among the warring factions.

Sincerely,

Joseph M. McShane, S.J.

Counseling and Psychological Services

Lincoln Center

140 West 62nd Street, Room G-02

Phone: (212) 636-6225

Rose Hill

O’Hare Hall, Basement

Phone: (718) 817-3725

Campus Ministry

Rose Hill

McGinley Center 102

441 E. Fordham Rd.

Bronx, NY 10458

Phone: (718) 817-4500

[email protected]

Lincoln Center

Lowenstein 217

New York, NY 10023

Phone: (212) 636-6267

[email protected]

University Health Services

[email protected]

Lincoln Center: (212) 636-7160

Rose Hill: (718) 817-4160

Office of Multicultural Affairs

https://www.fordham.edu/info/

Office of the Chief Diversity Officer

https://www.fordham.edu/info/

Department of Public Safety

(718) 817-2222

Jesuit Resources on Racism

https://ignatiansolidarity.

###

]]>At a Nov. 11 virtual event sponsored by Fordham and The Bronx Is Reading, which puts on the annual Bronx Book Festival, Rankine spoke about her new book Just Us: An American Conversation with Laurie Lambert, Ph.D., Fordham associate professor of African and African American Studies.

Through Just Us, Rankine narrates her personal experiences related to race and racism with white friends and acquaintances—and, in some cases, their own rebuttal to her stories.

“The book’s intention was to slow down these interactions so that we could live in them and see that we are just in fact interacting with another person, and that there are ways to maneuver these moments and to take them apart—to stand up for ourselves, to understand the dynamic as a repeating dynamic for many Black people, white people, Latinx people, and Asian people,” said Rankine, a Jamaica native who grew up in the Bronx.

Rankine has authored several books, plays, and anthologies, including Citizen: An American Lyric, which won the 2016 Rebekah Johnson National Prize for Poetry. Her other awards and honors include the 2016 MacArthur Fellowship, 2014 Jackson Poetry Prize, and fellowships from the Lannan Foundation and the National Endowment of the Arts. She currently serves as a chancellor for the Academy of American Poets and a professor at Yale University.

A Portal to Reflect on Your Own Life

At the evening event, Rankine said she wants her readers to use her as a portal to reflect on their own experiences and assess them, rather than simply live them. Reading Rankine’s stories can also serve as a restorative experience for some readers, particularly Black women, said Lambert.

“As a reader, I felt like I was being guided through these situations by a narrator I could trust—a narrator who understood a lot of my experiences as a Black person,” Lambert said to Rankine.

Naming ‘Whiteness’

The acknowledgement of a person’s “whiteness” can be perceived as threatening because it sounds similar to white nationalism and the violence associated with it, said Rankine. But “whiteness” is a necessary term when talking about race.

“The kind of clever thing that was done by white culture is the naming of white people as people. They are allowed to hide behind the generality of that statement. They are people and we are African Americans, Caribbean Americans, Latinx Americans, Native Americans,” Rankine said. “That’s how white people have negotiated their lives: We are just neutral people living our lives, and you all are people of color.”

This centralization of whiteness still stands in many places today, Rankine said. She cited the example of students and other people telling her they have received recruitment calls from white people who say they have perfect jobs for them, but they’re being “forced” to hire Black people to diversify their departments. This strategy to create equity is being falsely framed as something that takes something away from white people, said Rankine, who spoke at Fordham in 2016.

‘It Gives Me Hope’

Rankine acknowledged that it’s hard to confront covert racism. She’s had to train herself not to let things go—to stop saying she’s tired, that it will stop the conversation, that somebody else in the room should say something instead of her. It’s essential, she said, to hold people accountable because they make critical decisions with long-term effects on places like juries, boardrooms, tenure committees, and dissertation evaluation committees.

“We have been socialized so much towards silence and stability and not speaking up. And that’s what’s so amazing about the young people now—this new generation of high school students and college students,” Rankine said. “They are speaking up before things even get said. It gives me hope.”

Listen to the full conversation here.

]]>“It was America’s dead babies. I was trying to get my head around why so many babies, about seven out of 1,000 born, die before they turn 1,” said the New York Times columnist in an online conversation on Oct. 29.

Even though scientific achievements made over the last 50 years have dramatically increased the mortality of children born after 32 weeks, the mortality rate in the United States is almost double the rate in Korea, three times the rate in Japan, and six times the rate in Iceland, he said. Most of the U.S. babies who die young are also born to mothers who are poor and Black.

“The U.S. may be the richest country in the world, so the question is, why don’t we behave like one? It’s racial conflict,” he said.

In an online conversation hosted by Fordham’s departments of American Studies, Latin American and Latino Studies, and Sociology and Anthropology, Porter laid out the premise of American Poison: How Racial Hostility Destroyed Our Promise (Penguin Random House, 2020), which is that racism weakens American’s belief in one of the most critical components of a modern, functioning society: public goods.

“One of my core arguments is that Americans decided that if public goods must be shared across lines of race and ethnicity, they would rather do without them,” he said.

In his talk, which was followed by a response from Janice Berry, Ph.D., associate professor of economics, and a lengthy question and answer period, Porter said that although President Franklin Delano Roosevelt is lionized by liberals, his New Deal was colored by the stain of racial hostility. To win the support of white southern Democrats in the Senate, Roosevelt made sure that major parts of the legislation excluded anyone who was not white.

Porter cited several examples:, a major component of the New Deal that is credited with increasing homeownership, was a big contributor to redlining, a process by which predominantly black neighborhoods were declared blighted. The Civilian Conservation Corps, a work relief program created in 1933 that employed hundreds of thousands of young men, housed them in camps that were segregated by race. And when it was first created, Social Security excluded domestic and farm workers, the majority of whom were black

“This may offend those believers in the grand alliance of working men and women, immigrants, and racial minorities coming together to confront corporate leviathans, but that is what happened. Racism stymied the great liberal leap in American policymaking,” Porter said.

The civil rights movement provoked a backlash of the white majority against the idea of a society wrapped together by a common safety net, he said, adding that it was not a coincidence that Medicare and Medicaid, the last programs inspired by that ethos, were signed into law in 1965, one year after the Civil Rights Act. After that, he said, white Americans resisted the creation of additional social welfare programs.

“That same year, President Lyndon Johnson presented Americans with a ‘War on Crime,’ and a few years later, Richard Nixon offered this war as the new lodestar for American social policy,” he said, noting that for the next five decades, prison became the country’s preferred tool of social management.

Today, the country is considerably less healthy than its peers as a result, as measured by metrics such as the number of Americans living below the poverty line. And although technology advances and globalization are often blamed for the decline, Porter noted that countries such as France, Germany, and Canada have faced the same challenges.

“So when the good jobs went away, and wages stagnated, the bedraggled American safety net just could not hold the line. America’s dead babies, its bloated prisons, its idle men, its single mothers can all be traced to this exceptional fact: Americans chose to let those sinking sink,” he said.

“Why? Because a lot of those people sinking were people of color.”

Ironically, he said, these attitudes have betrayed white Americans as well.

“That part of white America that’s addled by opioids, ravaged by suicide, and despairing of a future is also a victim of a nation that refuses to care,” he said.

There is some hope that change is coming, he said, as the American population is growing more diverse. While three out of four Baby Boomers are white and non-Hispanic, only 55 percent of Americans born between 1981 and 1996 fall into that group. Eventually, Porter said, color lines are going to blur, and that the Black-white divide that has defined racial relationships for hundreds of years will soften.

Porter confessed that he is not very optimistic though.

“Minorities might eventually reshape American attitudes, but I would not discount the political clout of white voters trying to delay their decline from power,” he said.

The problem, he said, is that white voters in rural areas don’t interact with minorities, but they understand that minorities will eventually be moving into their towns, and it scares them.

“Conquering this fear, to my mind, is America’s most immediate challenge. The task of progressive politicians is to construct a public discourse that embraces America’s multiplicity of people,” he said.

“They must convince Americans to invite solidarity across lines of identity.”

To watch Porter’s lecture and Q&A, click here.

]]>With that, the issue of housing in American suburbs became an issue in the 2020 presidential campaign. Although the suburbs of today bear little resemblance to their cookie-cutter predecessors like Levittown, Long Island, they are still, in important ways, resistant to diversity and change.

To explore why that is, and how it happened in the first place, we sat down with Roger Panetta Ph.D., a recently retired professor of history and the author of Westchester: The American Suburb (Fordham University Press, 2006) and The Tappan Zee Bridge and the Forging of the Rockland Suburb (The Historical Society of Rockland County, 2010). He also co-wrote Kingston: The IBM Years (Black Dome Press, 2014).

Full Transcript Below:

Roger Panetta: How have I, as a white suburban resident, a former white suburban resident, contributed to this at the same time I espouse very liberal ideas about redistributive justice, about economic opportunity, about integration?

Patrick Verel: On July 29th of this year, President Trump shared this message with the world on Twitter, “I am happy to inform all the people living in their suburban lifestyle dream that you will no longer be bothered or financially hurt by having low-income housing built in your neighborhood. Your housing prices will go up based on the market, and crime will go down. I have rescinded the Obama-Biden AFFH rule. Enjoy.”

And just like that, the issue of housing in American suburbs shifted to the foreground of the 2020 presidential campaign. And although the suburbs of today bear little resemblance to their cookie-cutter predecessors like Levittown, Long Island, they are still, in important ways, resistant to diversity and change.

To explore why that is and how it happened in the first place, we sat down with Roger Panetta, a recently retired professor of history at Fordham and the author of Westchester: The American Suburb, and the Tappan Zee Bridge and the Forging of the Rockland Suburb. He also wrote Kingston: The IBM Years, which came out in 2014. I’m Patrick Verel, and this is Fordham News.

What is the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing or AFFH rule? And why is Trump so eager to advertise that he’s getting rid of it?

RP: Your opening statement about Trump saying how happy we should be because he is eliminating this rule is a wonderful example of his political genius. Fact-checking his statement, of course, gives us the general pattern of a pile of errors. The rule does not enforce any construction, any zoning law changes. In fact, the Fair Housing Assessment rule simply implies study. And it was meant to be a tool in order to enable the Fair Housing and the Affirmative Furthering Program to find ways to know and assess, by community, whether or not they were complying with fair housing rules. And deliberately and specifically, it required no actions by communities without public approval. So it did not threaten to build public housing, it did not threaten to build multiunit housing. In fact, it promised no change. It simply required an assessment of whether or not that community was complying with the fair housing regulations. That’s all it did.

So he very cleverly has escalated that. I think what he has done is struck a nerve, and a very important nerve, and that nerve is my house, my home, my community where I live. And that’s why it’s incredibly politically shrewd. He’s cut to the chase. Right to the heart of what it means to live in the suburbs, to own your house, your principal lifetime economic investment. And he has promised not to endanger that.

PV: As I understand that this Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule, which just really rolls right off the tongue, this came out of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which made it illegal to discriminate against people in housing. So this was an update to that 1968 act. Why would that be necessary? Why would there need to be an update?

RP: I think for about 40 to 50 years, the Fair Housing Act has not been able to successfully grapple with the issues of suburban housing and the segregation of suburban housing. So in order to try to give it some teeth without legislating the construction or the planning of those units, what it did is decided, let’s have communities do an inventory, assess where they are on the fair housing continuum, and tell us where they are and then suggest to us remedies they would make, that they would take, in order to create a more fair housing community where they were residing. So that’s all. And Obama was very careful, specifically implied there would be no imposed housing construction. So Trump’s saying there’s going to be public housing because of this action is absolutely inaccurate. I don’t think that matters. And I think to quarrel with him over the inaccuracies over this or whether or not the statements are fair misses the point. He’s striking a nerve.

PV: Besides legalized discrimination, which is what the 1968 act was meant to prevent, what were some of the other ways that suburbs were historically kept segregated?

RP: Now what Scarsdale and other communities had been doing for years is using restricted covenants. That is a group of community homeowners would agree, in writing sometimes, by specificity, naming the group, no Jews allowed, who could buy and purchase a home in that community. Some of those covenants actually got legal standing. It took a long time for the courts to overturn them, so community residents had formal written documents prescribing who could buy a home in that suburban community. And that expresses a fundamental problem here that people living in the suburbs want to live in a community of sameness. And that’s sameness is broad-based, it’s class, it’s ethnicity, it’s race, it’s probably political preference. It’s all of those things. And that they define as both comfort and safety. Those are the hallmarks of the suburb. And I think they’re very powerful and deeply embedded in the popular culture. Very hard to remove that.

And the long battle of Westchester, which Trump points to as ground zero, is very interesting. For almost a decade, they resisted the requirements of the Fair Housing Act to create more dense, racially mixed housing units throughout Westchester. And that was a bloodbath. It’s recently that they have conformed to that. And they’ve gone to introduce some community construction, but that bow is very interesting as a telltale marker about the way in which suburban communities resisted, politically, the notion of equal distribution of fair housing.

PV: Did you see the movie that they did on the guy in Yonkers? It’s like We Need a Hero, or something like that?

RP: Yes, so for a while I lived in Yonkers and there was a great diversity. And I remember a terrible, terrible story in my life. I lived in an apartment building that was racially integrated, 50% black, 50% white, and my wife were very committed to staying. And you could see it beginning to tip. You could see whites leaving in faster numbers. And there was a fire in the building one day and I had a two-year-old child and a fireman came up to me in the hallway. The fire was in our hall in the incinerators. And he said, “You know, those fires are caused by the super. He’s throwing paint rags down the incinerator, and you’re going to have an explosion.” And then he grabbed me by the throat and he said, “When are you getting out of this building?”

PV: Oh my God, really?

RP: Yes, he said, “When are you getting out of this building? What are you doing here? Why are you still here?” And he never said, of course, he meant, “Why are you as a white person are still here?”

PV: Wow.

RP: And that stayed in my head. And then we moved to Hastings. And when we moved to Hastings, my five-year-old daughter at that point said, “Where have all the black people gone?”

PV: I read that a 2018 survey experiment found that even politically liberal homeowners tend to oppose increasing development in their communities, even when they’re told that such development helps the disadvantaged. Any thoughts on how to counter that?

RP: Patrick, I thought that’s why your opening quote and the whole idea of this was so on target. It really gets to the very core of this issue we’re in now with Black Lives Matter. I wrote a letter to the president of the university and to the Bishop of the Episcopal church where I’m a member. And I said, “Really, I think what’s called upon now is for me to acknowledge my role in the patterns of racism. The blind privilege I have, and the advantages I have had as a white, professional, educated person.” I need to acknowledge those. And I think before I do anything else, I must create consciousness of how I fit in this in ways I do not see.

That’s exactly what you’re asking me here. How have I, as a white suburban resident, a former white suburban resident, contributed to this at the same time I espouse very liberal ideas about redistributive justice, about economic opportunity, about integration. But when it comes near my house, when you want to put multiple units in my community, when you want to put low-income housing, or fair housing in my community, you threaten the cost and the value of my primary life investment.

And when you do that, all of my political liberalism goes out the window. We need to confront that. And the studies you talk about raise another interesting issue, how and why do we not as a public know that about ourselves? So part of this question you’re asking is our sense of self-consciousness and self-awareness, do I understand what’s going on here? And I know what I feel. And it doesn’t matter to me if one black professional person moves next door to me, because that person somehow seems like me in some ways. It’s the notion of multiple units. It’s the notion of people I don’t know. So we’re prepared to allow slow accretions of blacks in the suburbs, but we’re not prepared for an open acknowledgment that the fundamental imbalance of that racially, and building the kind of multiple units in the centers, that we need to correct that. It’s a remarkable area of blindness, if not self-delusion.

PV: Do you think about this when you think about the ways that you… You were just telling me about how you moved from Yonkers to Hastings, which are very different places within Westchester. Do you think about that much now?

RP: Yes, I don’t know why. I think that was an important experience at Yonkers for my wife and I. I think we were very committed to that integrated living. We had terrific pangs of guilt when we left about what we had done. It was a matter of conscience, but that fireman shaking me by the neck, scared the wits out of me. And he pointed to my child and he said, “How could you be living here with your child? Are you a responsible father?” And I thought, “Gulp.” So it was a blow. It was a belly blow. And we continued to think about that. And so now, wherever I am, I tend to look around and see whether this place is white or black. Is this a mixed community? I can go four or five days and not see a black person? And that question always comes to my mind. I never want to let that go.

PV: Are there any suburbs that you’ve come across that have really embraced housing pattern changes that can be looked to as a model?

RP: There was a book recently done in 2019 by Amanda Hurley called Radical Suburbs. And what she did is she went back to the thirties and fifties and found experimental community developments in the suburbs that were based on more communitarian values, that were racially integrated, that had fair housing, inexpensive housing units, that really attempted to create and live up to the fair housing law before there was a Fair Housing Act. And that we have a history of that. That’s the irony. It’s not something we just need to look at places like Portland, where they have done a good deal of work creating more fair residential communities in the suburbs, but we have a history of it. And, again, it’s my deep feeling about our needing to come into contact with that information to realize about what were they trying to do, who were these places?

And, by the way, this also raises for me the other issue of the need to begin to study in our curriculums at the university level, the real estate history of the state, and the city, if not the country. Because in that real estate history, we have one of the fundamental issues of civil rights. American historians have been negligent in examining the place of real estate. And we live in a city that is governed and held by real estate. And we have a president whose reputation and power is rooted in real estate.

PV: Do you think we’re painting suburbanites with too broad a brush? Are there more progressives in the suburbs than we realize when it comes to this particular thing?

RP: Yes, and I think too broad a brush and really tells us about the power of popular culture in shaping our views of the world. I think we need to take a much more critical posture to how we know what we know and whether we think we know that. And so if I look at the white picket fence, the sort of house with a little backyard, all those images that really… The community of common people sharing common views. All of those very powerful images are stuck in our minds as what the suburb looks like. Tom Sugrue at NYU has done a lot of work in the last couple of years in trying to show us that the suburb is much more diversified than we think. And he has outlined a kind of phases of suburbs. For me, the easiest way to manage that, and for your audience, is to think of a series of concentric circles.

That series of concentric circles was first used in the 1920s at the University of Chicago to describe the development of cities. You can still use that now, and it’s very helpful to understand the suburbs. The suburbs have a series of concentric circles, not exactly, but it’s a helpful visualization. At the center of that may be the diverse suburb. And there are increasing numbers of those that Sugrue points out. Places like Yonkers, and the communities around Yonkers in lower Westchester. Indeed, lower Westchester is a good example of a diverse community that has a balance between, and the numbers fluctuate, between blacks, whites, and brown or Latinos. Those numbers also use the older housing stock to attract whites. So whites looking to buy houses find some of the old houses in Yonkers extremely attractive and affordable. So they buy them.

The end result of that process is to create a mixed suburban community. Now, the difficulties are those communities, those mixed communities, is they have a hard time holding the line. They slowly slide into segregated communities, which is a second form of suburban community. And that’s very old. We have black suburbs going back to the 19th century. And then in the third phase of the third circle of our concentric circles, we have communities that are mostly white. And then in the fourth circle, what we call the ex-urb, we have almost fundamentally white communities. That’s the Trump stronghold. So the profile is much more mixed than we tend to look and really has a much more politically diverse looking model for us.

PV: Yeah, it’s interesting. He should have been pitching not to suburban voters, but to ex-urban voters. It’s a whole different class.

RP: The point he’s also trying to make is that, and I’m fascinated by it, and I don’t know an answer to this, is this tipping point. When those diverse suburbs get too black or brown, and I don’t know what that number is, whites begin to leave and eventually diverse suburbs become segregated suburbs. It’s hard to hold on to them, their diversity. Now the question is why? What makes whites think, “This is going. I can feel it, and I have to flee?” And is there a way that we could subsidize those home values to stabilize those communities? We do not, I do not, you do not, we do not have experience of living with, working with African-Americans and browns the way we should. They remain, in our minds, the creatures of popular culture. So when my neighborhood increasingly becomes black, I think, “What do I know?” I go back to popular culture and it tells me what’s going to happen. Can we counter that? If we can’t, diverse suburbs all will eventually evolve or devolve into segregated suburbs.

PV: Why does red lining matter so much when it comes to the racial makeup of places like the New York metropolitan area?

RP: It’s a very good question because it gets behind the issue. It asks, what is the process by which these communities have been segregated and the way in which communities are shaped? And redlining is also a very good word, because it’s the actual red line that you would see on real estate maps. It’s the actual redline. And in historic documents, when we found those maps from banks, or communities, and you saw the red line, people said, “What was that?” And slowly they figured out it was used by banks to determine the value of property and where they would and would not grant mortgages. So redlining meant, if you were inside that red line, you were not going to get a mortgage. Indeed, the value difference between redlining and outside the red lining is about one half. So houses redlined were devalued by one-half houses not redlined.

PV: Wow, is that dramatic.

RP: Very dramatic. And then of course the difficulty is the banks think, “You’re asking for $150,000, but I valued your house only at $25,000. I can’t do that.” But I’ve made that number because I’ve redlined. And redlining is… And this is a word I want to hold on to. This is so pernicious. It’s hidden. People don’t see it, it’s subtle. It took a very long time from the 1930s to the 1970s to really outlaw the practice. And it still goes on. It goes on in other kinds of loans, it goes on and other kinds of banking procedures, it goes on in credit cards. It goes on in a whole series of things because I use those measures to determine whether you’re loan worthy.

PV: It reminds me of the conversations that you hear about race in the sense that racism hasn’t gone away, per se, it’s just that we’re better about using euphemisms to cloak it. So like when you think about a neighborhood you’re not talking about, “Okay, we’re not going to come out and say, ‘We don’t want a multiple dwelling apartment building because we don’t want poor people.'” You’ll say things like, “It’s going to ruin the character of the town.”

RP: What you’re talking about is the subtlety and sophistication of racism now. In a lot of communities where there have been proposals for multiunit housing, the very liberal community members respond to that by pointing to the environmental impact. So, “We’re not arguing about the unit, the numbers, or who. That building is going to damage our environment. And that has nothing to do with the race.”

PV: What gives you hope that things will change for the better?

RP: I don’t want to be a Pollyanna. And I don’t want to say I’m filled with hope. Because my first feeling about this problem is there’s something about it that’s intransigent. The government, political leaders, have had a crack at it for several decades and we have not moved the needle very far. It’s a problem that I think the public has found ways to dodge, to hide. And I think the word I keep coming back to how insidious this is. There is a battle here about whether this is a class or race issue, and suburbanites like to say, “I’ll let you into the suburb if you can really meet the economic level of life here.” So that’s a class issue. I don’t object to you based on race. We know from recent studies that the black incomes in the United States are going up, black professional incomes are going up.

The number of blacks with advanced degrees is going up. And the general economic condition, and the number of blacks in suburbs is going up. So all of those hallmarks tend to show that they’re beginning to have the badges that we have required for entrance into the suburb. So I tend to think that may be a method of change more readily than the way in which we tried to do this through the law.

As a matter of fact, this is a very good question, that people will qualify for what you think is the standard. And, again, “I’m going to let you in one by one, not in 25 units.” So the pace of this is abhorrent, but that’s where the change is coming. It’s very difficult, based on all the evidence and what you’ve said, to get communities to openly acknowledge, “We have been wrong here. We have to figure out a way how to change this.” I have a hard time seeing that change of consciousness unless I admit that I am part of the problem. And the first way the response, for me, to Black Lives Matter is to think, how have I contributed to this, and how do I change? I need to find ways to publicly say to my community, we need to open this up now. No matter what the danger is to what we think is our primary asset, our home value.

]]>That same year, he joined the faculty of the Gabelli School of Business as a lecturer in communications and media management, and in addition to teaching communications theory and corporate communications, he has worked as the college’s interim director of diversity, equity, and inclusion. We recently sat down—virtually, of course—with Ball, an award-winning competitive speaker, and speech coach, to talk about we can better understand each other during these turbulent times.

Listen below:

Full transcript below:

Clarence Ball III: I do not think that solving interpersonal racism, A, is possible within our lifetime. I also don’t think it’s necessary. We should really be trying to solve structural inequities or systemic racism because then we can attack the policies and not the people.

Patrick Verel: Of all the honors a business professor might snag, an Emmy would seem to be the least likely, but Clarence Ball III did just that in 2014 when he won one for the documentary, Looking Over Jordan: African Americans and the War. That same year, he joined the faculty of the Gabelli School of Business as a lecturer in communications and media management. And in addition to teaching communications theory and corporate communications, he has worked as the college’s interim director of diversity, equity and inclusion. We recently sat down, virtually of course, with Ball, an award-winning competitive speaker and speech coach, to talk about how we can better understand each other during these turbulent times. I’m Patrick Verel, and this is Fordham News.

In the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the worldwide protests that followed, people are having conversations about race issues in ways that they haven’t before. And I know many are struggling with how to proceed. How can we have productive conversations, especially since we can’t have them in person for the foreseeable future?

CB: That’s a really good question, Patrick. I think a lot of the allies at Fordham have been reaching out to me directly, some people that I know very well because we worked together a lot, and then other people that I’ve seen in passing, we work around the office together, just trying to stay connected. And what I’ve noticed from the allies is that there are some that are interested in other people seeing them doing the work, and there are some that are interested in doing the work privately. I don’t think either one is better or worse than the other, I think we just need to have the conversation.

But the people that have reached out to me privately, we’ve been able to have some more robust discussions. So I think if you know people that might be experiencing trauma from these issues, you might reach out to them directly and have more in-depth conversations before you go public with your thoughts.

PV: One of the things that seems to be key to the conversations about race is this idea that you can take a hate the sin, not the sinner approach. Do you agree with that and can you expand a little bit upon that?

CB: Yeah, I absolutely do agree with that. I agree because racism was done to all of us, right? It’s not just the people of color that have been victimized by racism. There are people that really do believe in supremacy that are of all colors, and that’s detrimental to all people.

So seeing that racism is something that was done to us through a series of laws and policies, right? Some people walked away from those laws and policies believing that they were better than other people. Other people walked away from those laws and policies feeling like they were less than other people. I don’t think that any of it is true. We’re all human, right?

And so I think when you go into the history of it and you look at indentured servitude, as opposed to slavery, you will see that many of the immigrants, I think two-thirds of all of the immigrants, arrived to British America under indentures, and that did not have respect of race. And you didn’t see race distinction in indentured servitude until the 1600s. So there was a case, John Casor, I believe against Virginia. And it was decided that because he was Black, his indenture would be for life. And from that case on, you see race kind of having this difference in regard to policies and how they treat us.

PV: You mentioned this idea of having these conversations kind of one-on-one, personal conversations as being more productive. Suppose you’ve reached that point now where you know you want to have that conversation with somebody about it. Any thoughts on how to go about starting that conversation?

CB: Yeah. I really think that you should begin having a conversation like that with a person that is ready to have the conversation. I do not think it is wise to force really difficult topics like race, structural inequities. I don’t think you should force conversations like that on people, but rather wait until they’re ready to have them.

Two things I want to add to this. Most of the times when people are having these conversations, it’s really to combat interpersonal racism. Interpersonal racism is when you have two people and, interpersonally, they don’t relate to each other until you’ve got these microaggressions and so on and so forth. And for whatever reason, people, their feelings, their emotions, they kind of want to sift through these issues. I do not think that solving interpersonal racism, A, is possible within our lifetime. I also don’t think it’s necessary. We should really be trying to solve structural inequities or systemic racism because then we can attack the policies and not the people.

PV: Talk to me about these summer workshops that you’ve been involved with at the Gabelli School. I understand you’ve been working with both undergraduate and graduate-level students. Can you tell me why is it so important to have these conversations about how to be an anti-racist now and what’s involved in these workshops in particular?

CB: So the Gabelli school is doing a lot of trainings. We’re doing a lot of lunch and learns, panel sessions, like you said. The impetus, I’ll share a few of them with you. We had a talk with the chief diversity officer, Raphael Zapata, and myself about a few weeks ago. And then from that talk, we just unpacked the different police cases that have been in the news lately. We shared some thoughts about that. We talked about structural and systemic racism, and we talked about the problem of interpersonal racism versus structural racism.

Recently last week, we had a different session, and this was with Gabelli Forward, which is under the programmatic umbrella of the graduate school. So at the graduate school, it’s really for our prospective students, which, in that case, would be people that have 10 to 15 years of work experience under their belt before we get them as students. And so what we tried to do was to have a discussion about being anti-racist in the 21st century, but gear it toward not only what we do at the university, but what might you encounter in the workspace.

The last thing is we’ve got these initiatives with Gabelli Launch, which is also under the graduate school’s programmatic umbrella. And Launch, this is for students that have already been admitted. And we have two programs. We’ve got one for executive MBAs. Again, this is our population. They’ve got 10 to 15 years of work experience. And so we’re going to have a more corporate discussion with them. We’ll take them through conflict personas, so on and so forth.

The other is for our Master’s of Science programs, which, demographically, have more international students than domestic students in our Master’s of Science programs. So that’s a different conversation that we’d like to have with them because they will come into the classroom here without the context of what racism is, particularly coming from where they come from. So we kind of give them a crash course of what racism looks like in America and why people on both sides are so emotional.

PV: Any surprises come out of it so far?

CB: Surprises? I was really surprised… We had a psychologist on the Gabelli Forward panel, and her research interests are in trauma that is related to racism. And so, listening to some of her findings from her dissertation and some of her research work that she does with Fordham, I found out that I’ve been traumatized and that there’s trauma like living in different places in my body, and that we all have trauma. It’s why we get so emotional if things don’t quite go the way that they should, and it’s a constant struggle between history and the things that you were taught and the things that you’ve seen, and then juxtaposing that with the move that the world is going into.

It’s a really emotional thing to do and I learned a lot academically from her during that panel that I don’t think I would have learned because I’m not sitting on a couch as much as I should.

PV: Right now, we’re talking in particular about these workshops, but is there anything else that you’ve picked up along the way since all this began that it’s kind of resonated with you?

CB: Yeah. I have a friend and she’s a history professor at Columbia. And her research is kind of like antebellum, postbellum reconstruction. And I’ve just been learning from her that the history lessons that I was taught in K through 12 were borderline inaccurate, and then, at best, omissive. Like there’s just so much that’s not there. And it is also structured in such a way where it really promotes a supremacy.

I am now unlearning so much, which is important, and we all will have to do some of that work in the midst of all of this, but I’m unlearning a lot. And then I’m going to find actual research, scholarly articles, to kind of reinforce a lot of the things that I missed in K through 12. And it’s helping me to get to know myself better.

PV: I felt that way when I was in grad school and I learned about redlining for the first time. I felt like I should have known about that way earlier in my life, given that I grew up in the New York City area. Yeah. Yeah, that’s interesting, the idea of unlearning things.

CB: I agree.

PV: Yeah, never too late to unlearn stuff, right?

CB: Never too late to unlearn. This is related, but not related. We’ve got a summer program right now and the kids are doing a project on redlining. And they’re finding out that New York, although it’s one of the most diverse places in the country, is also one of the most segregated when people go home to their neighborhoods.

PV: I guess it gets the reputation because everybody gets mixed up in the subway-

CB: Yes.

PV: And then when they go to work. But yeah, when they go home, not so much.

CB: Not so much.

PV: Yeah. Well speaking of New York City, you’ve been involved for the past two years with a partnership with Cardinal Hayes High School and Aquinas High School where you mentor Hispanic and Black students. How’s that gone so far?

CB: The program at Hayes and Aquinas has been pretty awesome for the Gabelli School. I mean, it does two things for us. First, it is a pipeline program. Historically at Fordham, students of color have been underrepresented. Let’s put it that way, right? And they’ve been underrepresented in such a way where now the university is trying to recruit students, right, that have the academic ability to survive in an environment like Fordham. It is a recruitment program.

So we work with the honors program at Hayes. These are very high achieving high school students with good test scores and good GPAs. And they are already interested or have been in conversations with Ivys and other really large institutions, research 1 institutions within the US. And yet, they really weren’t considering Fordham before this program. And so we’ve been able to go to the school as the Gabelli School of Business, teach them things about business principles like finance and marketing and strategy and operations, and then give them a project that is very closely related to the capstone of the sophomore year at Gabelli. And they learn it. And then they do this pitch proposal competition.

And in the midst of all of that, we’ve got Fordham students, which is, this is the other side of the coin, it’s a recruitment pipeline, and it’s also a community gaze learning initiative for our college students. So they are the college mentors that are in the classroom with the high school students walking them through the college assignments. And it helps the high school students, but it really reinforces the learning for the Fordham students, so that when they come into the class, they have reinforced their learnings about finance and marketing strategy, so on and so forth.

From the program, I think we’ve admitted about 10 students between Fordham College, GSB, and the Fordham College Lincoln Center at Rose Hill. And now, yeah, we’re going into year three of the program and we are looking to add a third institution, depending on whether or not we can do so virtually.

PV: Given that your expertise is in communication. Is there anything that you’ve kind of taken note of in the last two months that’s really made you hopeful for things to come?

CB: At the business college, a lot of the professors’ researched interests in various fields has some cross-pollination with conflict resolution. Even in management, they’ve got these organizational dynamics things that they do. And so what I’ve learned in the midst of all of this, is that serious conversations about race and inequities really involved critical conflict resolution principles. First thing, you’ve got to be willing to resolve the conflict, right? A lot of people come to the table for this particular conversation interested in learning, but not necessarily interested in resolving anything.

So you’ve got to come to the table ready to resolve conflict. And then when you do, you’ve got to really use best practices around listening and making sure that the other person is understood, and not using a hot button language or terms, so on and so forth. So that’s what I learned from this. And I know that it’s something that a lot of other professors at the Gabelli School are dealing with.

PV: Anything else you want to add before I let you go?

CB: The only thing that I’m thinking about within the context of Fordham in this conversation is it’s time for us to put our Jesuit values to work.

]]>“[George Floyd’s death] really puts us in position to look at something else that rears its ugly head all too often—not just in a macro sense, but in a micro sense at Fordham University, [in] corporate America—and it’s called racism,” said Carter, who retired as vice president for global diversity & inclusion and chief diversity officer for Johnson & Johnson in 2015. “We have to call it what it is, and we have to understand we all are affected and afflicted by this sin called racism. And we have to come together collectively to do something about it.”

A frequent lecturer and writer on the topics of diversity, inclusion, and social justice, Carter was a member of Fordham’s Diversity Task Force in 2015 and supports the University’s CSTEP program. He grew up in the South Bronx in a family of 10 children. His son Dayne is a 2015 Fordham graduate.

In part of the June 18 interview, Carter reflected on how his Fordham baseball cap helps protect him from people who may misjudge his identity and “take a cheap shot” at him.

“Outside of what we do, we still have to find ways to protect who we are,” Carter said. “I often use [this] example. I have a white cap, and it has a beautiful Fordham emblem on the front of it, and on the back of it, it says Board of Trustees. And I put that hat on like every other trustee with a sense of pride … But I also put that hat on for protection. I put that hat on because I don’t want anybody to misjudge who I am and take a cheap shot at me. Because absent that hat, I could be set up in circumstances that are unfortunate simply because of the color of my skin.”

In his role at Fordham, Zapata focuses on the support and strategic development of practices that promote racial justice, gender equity, disability access, and full participation in the life of the University among all members of the community. He’s a native New Yorker of Puerto Rican descent who grew up in the Chelsea public housing projects and attended Rice High School in Harlem.

Along with Carter, Zapata spoke about how Fordham is working on addressing racism within its ranks.

“At Fordham, we have … one of the oldest and widely respected African and African American history programs in the country … But not everybody’s going to be an African and African American studies major,” said Zapata. “What we’re trying to do at Fordham is [figure out]how do we integrate substantively and authentically issues of race throughout the curriculum in introductory classes? It can’t be an extra class, a one-credit class, or a zero-credit class. It has to be integrated into the curriculum.”

Achieving meaningful change is a process, said Zapata.

“What people think are the solutions are usually just the beginnings, and that includes hiring a chief diversity officer. That includes even getting a diverse student body, which we have not achieved yet. We’re still working on diversifying the faculty and administration and staff, which we’re working on. It’s a slower process. But we can’t pat ourselves on the back,” said Zapata. “We’re not there yet. And we have a long way to go.”

Watch Carter and Zapata’s full conversation in the video above.

]]>“Think about that question,” said Father Massingale, the James and Nancy Buckman Chair in Applied Christian Ethics at Fordham. “Why is it that the only group that’s never supposed to feel uncomfortable in discussions about race are white people? … We have to face the fact—and this is what I try to get at in my essay,” he said, referencing his recent op-ed in the National Catholic Reporter, “is that the only reason why racism still exists is because it benefits white people, and there is no comfortable way of saying that.”

In an hourlong online conversation on June 4—amid national protests against police brutality and racial injustice following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police—Father Massingale spoke with Olga Segura, a 2011 graduate of Fordham College at Rose Hill and former associate editor of America Media, on how systemic racism impacts the church and how fellow Catholics can help dismantle it. John Gehring, the Catholic program director of Faith in Public Life, a national network of nearly 50,000 clergy and faith leaders, moderated the discussion.

In his book Racial Justice and the Catholic Church (Orbis Books, 2010), Father Massingale reviews and analyzes the major statements on race that the church has made since the 1950s and offers recommendations to improve Catholic engagement in racial justice.

“It’s not true to say the Catholic Church has said nothing and done nothing. But what the Catholic Church has said and done is always predicated upon the comfort of white people and not to disturb white Catholics. And if you make that your overriding presumption and goal, then there are going to be difficult truths that will never be spoken, and we will never have an honest conversation,” said Father Massingale, who teaches theological and social ethics at Fordham.

The online forum began with a recollection of recent events, including not only the killing of George Floyd but also the recent death of another Black man, Ahmaud Arbery, who was shot and killed while jogging through a Georgia neighborhood, and an incident in Central Park in which a white woman called 911 to report that an unarmed “African American man” who had asked her to comply with the park’s rules to keep her dog on a leash was “threatening” her life.

“That all moved me to the sense of, how long, how long do we have to continue to endure the humiliations and the terror that come with being Black, brown, other in America?” said Father Massingale.

These are things that are especially important for white people to hear, said Gehring.

“Part of white privilege, as you all know so well, is the ability not to have to think about this. I’m someone who’s tried to learn as much as I can about the history of the United States, but I will never know what it means to be a person of color in this country,” he said.

In their conversation with Gehring, Segura and Father Massingale made several points about how Catholics and others can acknowledge white privilege and confront racism on a personal and institutional level.

Racial injustice is a pro-life issue. In a recent statement, Pope Francis said Catholics cannot “tolerate or turn a blind eye to racism and exclusion in any form and yet claim to defend the sacredness of every human life.”

When asked to comment on the pope’s statement, Father Massingale said, “At last, someone in high authority has been saying what people of color again in the Catholic Church have been saying for a long time—that racism is a life issue.”

For too long, “we’ve framed concerns of pro-life around a very narrow meaning of being anti-abortion,” said Father Massingale. But it is impossible to support policies—in education, health care, and criminal justice, for example—that are “detrimental to the lives of people of color, and yet call ourselves pro-life,” he said. Segura agreed.

“As Catholics, we’re doing a disservice to ourselves and our church when we say we’re pro-life, but are unwilling to sit with the most significant civil rights movement since the ’60s,” said Segura, who is writing a book on the Black Lives Matter movement and the Catholic Church.

Racism is a religious and spiritual challenge—not just a political issue. The civil rights movement was successful because it spoke with moral authority, said Father Massingale. To show their support for racial justice and solidarity with people of color, Catholic bishops could visit “shrines that we’ve erected where Black lives and bodies have fallen and lead a rosary there,” he said. And Catholics don’t need to wait for bishops to act. Bishops “bear a unique symbolism and responsibility,” but lay activists and leaders should participate, too. By bearing witness and walking with their Black brothers and sisters, they can send the message that “you cannot be a good Catholic and not be concerned about what’s happening here,” he added.

Put yourself in another person’s shoes—and ask your friends and family to do the same. A good way to do this is through Ignatian spirituality, said Father Massingale. “If we use the tools of our contemplative traditions, whether it’s Ignatian or Carmelite or whatever, and have people dwell there, that’s when you have affect and faith meeting. And that gives us the tools, the possibility for a breakthrough—a breakthrough that won’t happen if you try to engage in talking points,” he said.

One example is to imagine what it’s like to lose your child in a retail store, said Father Massingale, who once worked in retail store security. “Parents would come to us in a panic,” he recalled. “The joy, the relief … you could see people begin to breathe again when you’d reunite them with their kid. … And the kid was only gone for a matter of minutes.” He urged the audience to ask their family members to imagine another situation: what it’s like to have your child shipped out of the country, with no idea where they are.

“To just sit in that agony, to sit in that desolation … I can’t imagine what it’s like to be a parent and to even contemplate that,” he said.

Be careful of polarizing people, but hold them accountable. Segura said she has seen lists that separated Catholic parishes into those have either recently addressed or not addressed racism. She urged people to publicly speak about where parishes have succeeded and failed. “If you see that your priest has not mentioned race once this month or in May, talk to him about it,” said Segura.

Our national policing culture is broken. “We need to make a crucial distinction between supporting police officers and reforming the culture of policing. Too often we get distracted by saying that if we criticize the police, then we’re denigrating the good, law-abiding officers,” said Father Massingale. “We need better guidelines to train our officers on the appropriateness of lethal force, when it’s appropriate to use it, how to train people on de-escalation procedures, but then also create those mechanisms that can hold officers responsible when they abuse [their power].”

To fight against police brutality, we also need to educate ourselves and demand that our local leaders are transparent about the funding behind police departments, added Segura.

Listen to people’s sadness and grief. “We, as persons of color, we have marched, we have demonstrated, we have petitioned, we have boycotted, we’ve voted, we’ve written op-eds. We’ve bled, we’ve prayed, we’ve begged, we’ve pleaded, and we’ve done that for years, for decades, for centuries,” said Father Massingdale, “and still we’re in a country where a Black man can’t go jogging without being stalked and killed.” He stressed that he doesn’t advocate violence. But he added that not all of the violence done by protestors has been “done by people of color,” and in some places, there is more concern about violence done to buildings than violence “that’s been inflicted on Black and brown bodies and Black and brown communities for so, so long.”

The pandemic also makes it more difficult to grieve, especially for people of color who have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic, Segura said.

“Many of us have been reporting and talking about [racial injustice] for years, but this is the first time where I’m forced to try to reconcile with what it means to privately grieve with my community, privately grieve with my family at a time when we cannot physically be together,” she said. “We have to rely on phone [and video] calls. Black and brown Catholics are very much about being in physical community with each other. So what does it mean for me to try to grieve everything that’s happening at a time when we can’t be together?”

To enact change, we must engage in a relay race. Segura said she has been inspired by Father Massingale’s work, particularly Racial Justice and the Catholic Church, which she said helped shape her faith and her understanding of what it means to care about racial justice in the church.

“If you hadn’t written your book, I would’ve found it very hard to write my book in 2020,” she said to him over the live video chat.

Father Massingale said it is wonderful to see someone so young and energetic add her voice to their ongoing struggle.

“I’m not going to live forever. … I’m probably going to pass on before we reach whatever racial promised land we’re coming to,” said Father Massingale, who is 63 years old. “But I do what I do for the sake of those who both were ahead of me, to honor their work, and for those who are coming up behind me—people like Olga and so many others. … It’s going to be an intergenerational process. But we have to start now.”

The full recording of their discussion can be viewed on Facebook.

]]>

Khan, who goes by the pronouns they, their, and them, began their Jan. 23 talk by telling a travel story that illustrates how embedded racism and bias can impact day-to-day interactions.

“I am late for a connecting flight, and I’m rushing through the airport and I get there and I just happen to be in first [class]this time,” Khan, who is now based in Los Angeles, said to a standing-room-only crowd of students, faculty, and community members in a Fordham Law lecture room. The event was part of Fordham’s week of programming in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“And right above my head the overhead space is full. So I look behind and there’s one, there’s an empty space, and I’m late enough where everyone is settled in. And as I’m about to, in a very practiced way, swing my bag up there, an older man pops up and he goes, ‘Uh, I’m sorry, ’scuse me, do you belong here?'”

Khan said that they paused for a few seconds and stared back at the man who they said didn’t have “a malicious bone” in his body.

“You know it’s funny … I’ve read all the books, I’ve had all the conversations, I’ve been on the frontlines … I have had all the debates that you could possibly imagine, and still there’s never a way to respond to these things,” Khan said. “There’s no set way to know how to unpack this exchange that’s happening between us in 10, 15, 30 seconds, and so I just stare at him.”

Khan said that they saw something happen on the man’s face and he quickly apologized, lifted the carry-on onto the rack, and retrieved it after the plane landed.

“I tell this story because the word ‘belonging’ is something that keeps coming up for me and in this work,” they said.

Khan was the keynote speaker for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. week, which aimed to honor King’s legacy and explore the impact of his work—and that of the civil rights movement—on today’s civil and human rights agenda.

They said that they told the story from the plane because it embodies their work on pushing for equality and justice for people of color, those who are LGBTQ+, those who some consider “outsiders.”

“It was in that moment that so many other things make sense—a black kid selling lemonade on the corner who gets the police called on them, a black man walking down the street who has the police called on him, a cookout with a group of black people and they have the police called on them,” they said. “We come up with these amazing memes and they’re so funny—BBQ Becky and all that—but ultimately there is a reason why these people feel like they need to regulate space. When you are taught to believe that you have more ownership of a space, of a society, of a country, of an institution, whatever it is, then it becomes your job to keep those who don’t belong out.”

Khan called on those in the audience to actively seek to build bridges to others who are different, as a way to combat supremacy.

Khan called on those in the audience to actively seek to build bridges to others who are different, as a way to combat supremacy.

“If you don’t seek me out, and I don’t seek you, we have accepted the terms of white supremacy in this country,” they said. “We have accepted its conditions. We have accepted its parameters. When you decide that my life is of lesser value than yours, when we do not take personally the things that are happening to the populations of other people, understanding that if they’re coming for me tonight, they most assuredly will be coming for you tomorrow morning, if we aren’t beginning to take these things personally, we aren’t going to win.”

The office of Rafael Zapata, Fordham’s chief diversity officer, sponsored the lecture and the rest of the week’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. events. Zapata said that Khan “embodied this spirit” of King, which included pushing back on “norms” that are wrong and fighting for social justice and equality.

“When the movement went from the Deep South, and the unambiguous repudiation of racist acts and hatred, to systemic racism in the North and segregation, he lost many friends and I think that courage and that evolution is lost,” he said.

Zapata said that activists like Khan have helped to keep the movement alive and the work ongoing. “When I read some of the writings of Janaya Khan, I think of Black Lives Matter in that longer trajectory of slave rebellions, of abolitionist movements, of post-reconstruction communities, of literary movements—W.E.B. DuBois, Ella Baker, Audre Lorde, and so many nameless others—and we’re thankful that they’re here today.”

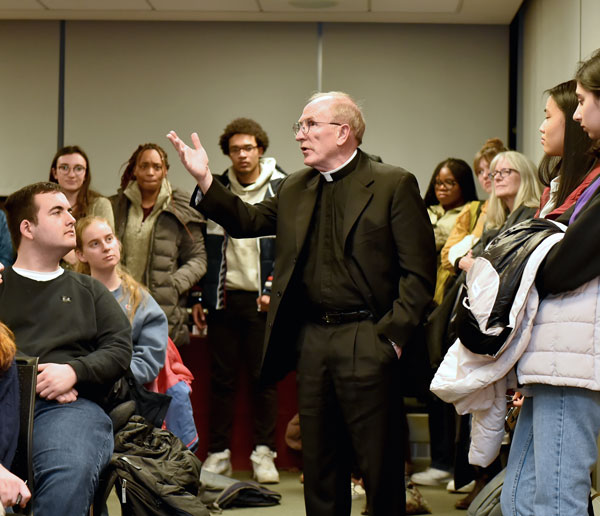

Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, said that Khan’s speech, which also included a call for economic justice, as well as social justice, encouraged those in attendance to examine their own selves and work for change they want to see in the world.

“It’s an invitation rather than a lecture,” Father McShane said. “You took us through one of the difficult conversations, which is a necessary conversation, and it’s necessary because it’s a prophetic conversation and you did it in a masterful way. I can’t tell you how moved I was by what you did.”

]]>