Brian Lyman, who has been immersed in Alabama state politics as a reporter for nearly two decades, was named a 2024 Pulitzer Prize finalist for his “brave, clear, and pointed columns that challenge ever-more-repressive state policies flouting democratic norms and targeting vulnerable populations.”

For Lyman, a 1999 Fordham graduate, it was the latest milestone in a journey that began at the University’s Rose Hill campus a quarter century ago, when he was the opinion editor of The Fordham Ram.

He previously worked at the Montgomery Advertiser, the Press-Register, and the Anniston Star—and last year, he became the founding editor of the Alabama Reflector, a nonprofit outlet that’s part of States Newsroom, a group that aims to bolster state-level reporting across the country.

What was it like finding out you were a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize?

We have this huge story running, and I’ve been deep in editing it, so I was not actually listening to the Pulitzer announcements. A friend who’s working in Nashville texted me, “Congratulations on the Pulitzer!” And I texted her back, “Wait, what?” Then my colleagues ran in telling me, so I may have been the last person to find out.

In your commentary you focus a lot on major issues—crime, the death penalty, transgender youth. How do you pick the topics you want to dive into?

The transgender issue has been going on for almost three years now in Alabama, but the column [cited by the Pulitzer board] was [published in April], when the latest [transgender sports] ban was moving toward passage. It just felt like it was something we needed to let people know. “Oh, by the way, this extremely small, extremely vulnerable group is being targeted by your lawmakers, and we need to pay attention to this.”

Some issues, like the column I did about prisons, legislators aren’t really talking about, because it’s not an issue that wins votes, and it’s something they would rather not deal with. But I’ve been inside those prisons. You don’t need to read the Department of Justice reports on the violence within those prisons to be horrified. So, it was just a way of trying to remind people there’s a huge humanitarian crisis that the state government is not dealing with.

And sometimes it’s both an issue in the news and something that happened in real life. My column about the libraries (“The most dangerous idea in a library? Empathy”) was provoked by my daughter just asking me about the value of reading.

Those issues are at the center of a lot of national conversations too. How do you see your role in covering them in Alabama as they go beyond your state?

I said in the opening column when we launched the Reflector, Alabama is the place where America confronts itself. This is where we see the very best and the very worst of the American character.

Let’s talk about the negative side: We still work under a state constitution passed in 1901 that was framed deliberately to disenfranchise Black Alabamians and poor white [people]. You have a government that’s habitually uninterested in really helping address issues of poverty, which are rampant in Alabama. It’s a government that constantly jumps at moral crises that really don’t have any impact on the day-to-day lives of people.

On the positive side of things, almost every major Civil Rights event that took place between 1955 and 1968 came from Alabama. It’s not just Rosa Parks. It’s not just Martin Luther King. It’s school funding issues, it’s voting issues. New York Times versus Sullivan came out of Montgomery. There are brave men and women in this state who constantly demand better. When they demand more, they lead to these great decisions that have, sometimes slowly, pulled Alabama forward. I feel like our role is just to make sure that all these good people in Alabama know what their state government is doing so they can take the appropriate action to support it or, more often, oppose it.

Thinking back to your time at Fordham, do you have things you learned here that you still use today?

It’s been 25 years since I graduated from Fordham, but I feel like everything I do is basically what I did at The Ram, just more—short ledes, hitting deadlines, making as many phone calls as possible. We learned from our older colleagues, and then we passed it on to our younger colleagues. And we did some great things. One editorial sticks out. An LGBTQ group applied for club status and was denied for whatever reason—this is 1997, I think—and we wrote a very lengthy editorial blasting that decision. I was always very proud that we did that.

Now, on the other hand, it’s obviously a student newspaper, so we had some mistakes. It was fall of 1998, and I think it was Daniel Berrigan who taught a class called Poems by Poets in Torment. It’s the end of the semester, and this ends up on our front page. And this story, I swear goes through six pairs of eyes, including my own, and none of us notice that we have named the class Poems by Pets in Torment. I did not hear the end of that for months.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Kelly Prinz, FCRH ’15.

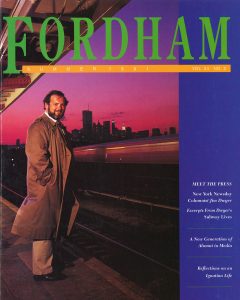

]]>“The angels have a bard. Fordham, and New York City, mourn the death of Jim Dwyer, who was truly the voice of average New Yorkers,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “One could write a book of several volumes extolling Jim’s virtues and his contributions to the city he loved and chronicled. He was a true son of Fordham, and of New York. Our hearts go out to Jim’s wife, Cathy, their daughters, Maura and Catherine, and their loved ones. I know the Fordham family joins me in prayer for them as they grieve Jim’s loss.”

Over more than four decades in journalism, Dwyer sought to tell the stories of everyday New Yorkers and give voice to those on society’s margins, including working-class immigrants, racial and ethnic minorities, and people convicted of crimes they did not commit. Through his reporting and writing, he worked to help the public understand the impact of major issues and events, most notably 9/11, as well as the inner workings of government agencies and how their decisions affect people’s lives.

“Dwyer had boundless energy, tremendous muscular intellect, and always great empathy for people,” said Thomas Maier, FCRH ’78, an award-winning journalist and author who worked with Dwyer at The Fordham Ram and New York Newsday. “He had a lot of brain, but he had an even bigger heart.”

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, FCRH ’79, one of Dwyer’s Fordham classmates, said his passing was “a great loss” for journalism and for the people of New York.

“He was … a great New Yorker and a powerful voice for many, many years,” Cuomo said. “Jim Dwyer was about the discovery of the truth, and he was brilliant. He was hard working. He also was a poet. He had … the ability to connect with New Yorkers, to take complicated subjects, find the truth, and then communicate it to New Yorkers in a way they understood.”

Covering the Coronavirus

Last spring, in his final columns for The New York Times, Dwyer wrote about the coronavirus pandemic. In one piece, he illustrated how at the height of the pandemic in March, Elmhurst Hospital in Queens was overwhelmed, while “3,500 beds were free in other New York hospitals, some no more than 20 minutes from Elmhurst, according to state records.” In another piece, he delivered a farewell to an Upper Manhattan bar forced to shut its doors permanently: “Coogan’s was the promise of New York incarnate: multiethnic, friendly, welcoming, smart,” he wrote. “The premise of the business was the opposite of social distancing.”

And in a poetic final column, he wove together a tale of his own family history during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic with a chronicle of the thoughts and experiences of three New York City hospital workers responsible for feeding patients during the coronavirus pandemic. He related their ministrations to those of his great-grandmother Julia Neill Sullivan, who in her early 70s “marched pots of food from her hearth across a stony field on a remote peninsula along the west coast of Ireland” to keep her family alive when they were too sick to feed themselves.

“In times to come,” Dwyer wrote, “when we are all gone, people not yet born will walk in the sunshine of their own days because of what women and men did at this hour to feed the sick, to heal and to comfort.”

The Birth of a Big-City Journalist

Jim Dwyer was born and raised in Manhattan, the second of four sons of Irish immigrant parents. His mother, Mary, was a registered nurse at Bellevue Hospital, and his father, Philip, was a custodian in the New York City public school system.

His upbringing and education instilled in him a sense of justice from when he was young, his brother Patrick Dwyer, FCRH ’75, GSAS ’77, LAW ’80, said.

“I do credit Catholic school education for [his sense of justice],” he said. “He had a real conscience [and] he poked everybody else’s conscience. If you didn’t have a voice, he would figure out a way to make your story important to other people.”

He attended Loyola School, a Jesuit high school on the Upper East Side, where Patrick Dwyer said he got a taste for journalism, helping revive the student newspaper there. He said he recently received a call from the president of the Loyola School, who shared a story about a former president who complained about “what a pain” Jim Dwyer was for his work with the newspaper.

“Once a week, you know, [he would] get something out that was complaining about this injustice or that injustice, and what was a pretty fine prep school,” Patrick Dwyer said with a laugh.

He earned a full academic scholarship to Fordham, and initially intended to become a doctor.

In 1976, however, an encounter on Fordham Road changed the path of his life. Dwyer was driving when he witnessed a man having a seizure on the sidewalk. He and a few others stayed with the man and learned that he was a Vietnam veteran who had been having seizures since returning from the war.

Dwyer wrote about the experience for The Fordham Ram, and the article won a national award from the Society of Professional Journalists, due in part to his captivating lead paragraph: “Charlie Martinez, whoever he was, lay on the cold sidewalk in front of Dick Gidron’s used Cadillac place on Fordham Road. He had picked a fine afternoon to go into convulsions: the sky was sharp and cool, a fall day that made even Fordham Road look good.”

Bitten by the storytelling bug, Dwyer was helped along the path to a career in journalism by Raymond A. “Ray” Schroth, S.J., a communications professor at Fordham who became a lifelong mentor and friend, and even served as the family’s priest, presiding over weddings, baptisms, and funerals. Father Schroth, who died earlier this year, helped connect Dwyer with Maier, who was then an editor with the student newspaper.

“I would say it was probably my personal biggest contribution to journalism, getting Jim Dwyer onto The Fordham Ram,” Maier said with a laugh.

By his senior year, Dwyer was editor-in-chief of The Ram.

“I lead a double life,” he said in a 1979 Fordham marketing brochure for prospective students. “I edit The Ram and I’m majoring in science. The newspaper takes 50 hours a week of my time, so if you ask me how I manage to survive academically, I couldn’t tell you.”

Jim O’Grady, FCRH ’82, a reporter, host, and editor at WNYC, joined The Ram as a staff writer during Dwyer’s senior year.

“I remember walking into the composing room for the newspaper—back then it was made by hand, and the strips of copy that would become columns in the newspaper were hanging on the wall, because they had to dry before they could be pasted onto the board,” he said. “So you can see people’s writing styles next to each other in these strips of paper. And we were all novices, so our writing styles ranged from inept to largely overwritten. But then you saw Dwyer’s strip of writing. And it was just different. It was crisp. It was polished. It was authoritative. And you knew this guy was going on to something big. This guy already got it.”

As an undergraduate, Dwyer began dating a Fordham College at Rose Hill classmate, Cathy Muir, and they were married at the University Church in 1981, with Father Schroth presiding. The year prior, Dwyer had earned a master’s degree from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, where he said he truly knew journalism was his calling.

“I would come back from an assignment, my notebooks full, ready to write, and a little smile would break across my lips,” he told Fordham Magazine in 1991.

Finding His Voice Underground

Dwyer got his professional start in journalism in New Jersey, working at The Hudson Dispatch, Elizabeth Daily Journal, and The Bergen Record before taking a job at New York Newsday, where he made the most of a new assignment—subway columnist. His goal was to tell stories of everyday people and how they were affected by the world’s largest transit system, and before long, the paper was billing him as “New York’s real transit authority.”

He won a Pulitzer Prize in 1995 for “his compelling and compassionate columns about New York City.” He had also been part of a team that won the “spot news reporting” Pulitzer for its coverage of a 1991 Union Square subway derailment that killed five people.

Maier, a colleague of Dwyer’s at New York Newsday, said Dwyer’s reporting helped determine what really caused the derailment.

“It was Jim who had the sources and found out that the motorman had been drunk, and that was the front page of Newsday and that was what led to New York Newsday winning the Pulitzer Prize,” he said.

While at New York Newsday, Dwyer also became known for his work related to wrongful convictions, particularly the 1989 case of the Central Park Five, in which five Black and Latino teenagers were arrested for raping a white woman in the park. The teenagers confessed to committing the crime, but Dwyer pointed out that there was no forensic evidence linking them to the scene, and he questioned the police interrogation techniques that led to the confessions.

In one of his pieces on the case, referring to a police transcript, Dwyer wrote, “No New York jury is going to be convinced that this confession contains the language of a New York kid.” A jury convicted the teens, nonetheless. Four of them served more than six years in juvenile facilities, and one, tried as an adult, served more than 13 years in state prisons. In 2002, a convicted rapist confessed to committing the crime. DNA evidence linked him to the scene, and the teens’ convictions were ultimately vacated.

In the 2012 documentary film The Central Park Five, Dwyer reflected on the circumstances that led to the teens’ wrongful imprisonment. “This was a proxy war being fought,” he said. “And these young men were the proxies for all kinds of other agendas. And the truth and the reality and justice were not part of it.”

Patrick Dwyer said his brother pursued stories the same way he played sports in high school.

“As an athlete in high school, he was a bull,” he said. “And that’s pretty much the way he did his journalism. He would keep asking the questions until he got the truthful answer.”

Chronicling Personal Stories of Heroism and Lessons Learned from 9/11

After New York Newsday closed in 1995, Dwyer was a columnist for the Daily News, before joining The New York Times as a reporter in May 2001.

Four months later, he helped shape the paper’s coverage of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. He wrote a series of stories about objects from Ground Zero, like a squeegee a group of people used to escape from an elevator just before the south tower collapsed. And he worked with fellow reporter Kevin Flynn to chronicle in painstaking detail what happened in the twin towers from the moment the first plane hit the north tower until both towers had fallen. Their work, based on hundreds of interviews with survivors, was published as 102 Minutes: The Unforgettable Story of the Fight to Survive Inside the Twin Towers (Times Books, 2005), one of six books he would author or co-author.

In 102 Minutes, Dwyer and Flynn “stitched together a narrative that’s as compelling and suspenseful as it is excruciatingly sad,” Fordham Magazine wrote in 2005. They also documented failures of communication and missteps made by the city and the towers’ developers that came at a terrible cost on that tragic day.

Dwyer credited his science studies at Fordham with helping him tell stories that combined an understanding of technical concepts with a profound sense of human drama.

“If you’re not interested in the engineering of things … you become a servant of whatever people tell you is going on,” he told Fordham Magazine in 2015. “You’re at the mercy of experts.”

Beth Knobel, Ph.D., associate professor and associate chair for graduate studies in the communication and media studies department at Fordham, said that one of Dwyer’s biggest assets as a journalist was an ability to keep his subjects as the focus of his stories.

“He managed to keep himself almost invisible. While so many journalists sometimes make stories about themselves, Jim always kept his focus on the subject,” she said. “The way he used language and imagery spawned a lot of admiration and more than a little jealousy. I wish I had a dollar for every time I read something he wrote and thought, ‘Wow, how does someone put words together like that, with such precision and power?’”

A Commitment to Journalism That Saves and Salvages Lives

Kevin Doyle, FCRH ’78, met Dwyer when the two were undergraduates at Fordham, and they became lifelong friends, each eventually asking the other to serve as godfather to one of their children. “I was a dabbler in journalism [at Fordham]; he was a master of it even then,” said Doyle, a lawyer who has defended death-row inmates in Alabama and who led New York’s Capital Defender Office from 1995 to 2007, when the death penalty was abolished in the state.

He said that Dwyer used the “About New York” column in The Times as a platform to elevate people and causes that he felt needed attention.

“He understood the power that he had, by dint of his journalistic charge, but it never went to his head,” Doyle said. “It was always a tool rather than a prize for him.”

Doyle pointed to Dwyer’s 2012 story about Rory Staunton, a 12-year-old boy who died of sepsis, as an example of journalism that saved “thousands of lives.” Staunton went to NYU Langone Medical Center a few days after diving for a basketball and cutting his arm on a gym floor. He was feverish and vomiting, and he was discharged without being tested for sepsis. Within three days, he died. His parents, in part through sharing their son’s story with Dwyer, embarked on a campaign that eventually led New York to order hospitals “to quickly identify signs of sepsis and begin treatment.”

Five years after the initial story, Dwyer followed up and found that from 2011, before the regulations were implemented, to 2015, 4,727 fewer people died from sepsis.

“Jim wrote about this and as a result now they do [early testing], and you know, it’s saved many, many lives,” Doyle said. “He both saved lives and he salvaged lives with exoneration work.”

In late 2018, Dwyer returned to Fordham to celebrate the 100th anniversary of The Fordham Ram. The editors of the paper had invited him to serve as the keynote speaker at a centennial dinner held in Bepler Commons on the Rose Hill campus.

“If you’re a news reporter, you need to hope for humility,” Dwyer said that night. “And own your own mistakes.”

Knobel said that Dwyer’s address that night was a “love letter” to journalism.

“As in his reporting and column, Jim made it clear to the alums and young reporters there that journalism is really about telling other people’s stories and is one of the greatest ways to spend one’s life,” she said. “The talk was charming and self-effacing and powerful, just like Jim’s work.”

A Generous Colleague, Friend, and Mentor

Maier said that Dwyer was willing to help fellow journalists, whether by recommending a source for a story or even sending a story their way. He recalled that about two years ago, he got a call from an attorney representing a man named Keith Bush, who had been convicted of the murder of a Long Island teen in 1976, but always said he was innocent.

Maier worked on the story for about a year, publishing a 16,000-word investigative report on the case and putting together a documentary on it—all without telling Dwyer, because he didn’t want his friend and former colleague to write about it first.

“I reported out the whole story, that’s almost an entire year, fearful that Dwyer would scoop me on the story for The New York Times,” he said.

Only after Bush was exonerated, on May 22, 2019, did Maier find out that Dwyer was the one who told the lawyer to call him.

Doyle said that outside of work, Dwyer was also known as a loyal, caring, dedicated friend.

“He was always eager to help—he’d drop whatever he was doing. He was a problem solver, inside his family and to his friends,” Doyle said.

O’Grady said that while Dwyer’s passing is a loss for journalism and Fordham, his work and teaching live on in the young journalists he mentored.

“We’re losing a legendary reporter, who was still in his prime, but who spent countless hours mentoring future generations of journalists,” he said. “He’s still with us in the many Fordham students he spoke to and inspired, and people all across the profession who he helped and encouraged.”

Patrick Dwyer said that his brother and his voice will be missed.

“We were extraordinarily proud of him,” he said. “I spoke to a friend yesterday … and I said, ‘You know what, I actually feel that we got it right. The esteem we held him in was apparently shared by everybody else.’”

He is survived by his wife, Cathy Dwyer, FCRH ’79; his two daughters, Maura Dwyer and Catherine Elizabeth Dwyer; and his three brothers, Patrick Dwyer, Phil Dwyer, FCRH ’80, and John Dwyer.

]]>

Photo by Janet Sassi

In the 19th century, the central moral challenge was slavery; in the 20th century, it was totalitarianism; but in this century the issue dominating moral debate is gender inequity, journalist Nicholas Kristof said at Fordham Law School on Feb. 22.

At an event sponsored by Fordham’s Leitner Center for International Law and Justice, Kristof and his wife, Sheryl WuDunn, showed slides of extraordinary women from developing countries who have transformed their lives through international aid and intervention. The Puliter-prize-winning pair have traveled around the world to uncover and publicize human rights abuses. Recently they collaborated on Half The Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide (Knopf, 2009), a series of first-hand accounts of women they have encountered in their research.

One story involved 13-year-old Cambodian Long Pross, sold into sex slavery, her left eye mutilated by the brothel owner when she would not have sex following a forced abortion. Pross, however, was rescued by a trafficking survivor who had herself been rescued by a survivor.

Another teenager, Srey Neth, was bought out of sex slavery by Kristof for just $150 and returned to her family; she went on to become a successful grocery store owner in her village.

WuDunn relayed the plight of 14-year-old Ethiopian Mahabouba Muhammad, whose obstructed labor from a rape left her incontinent, and thus ostracized from her village. The homeless teen was rescued by a missionary after she was attacked by hyenas. Today, she is a nurses’ aide at Adis Ababa Fistula Hospital.

These accounts and others, Kristof said, are examples of “the brutality inflicted routinely on women and girls,” particularly in developing nations. He offered staggering statistics on women and mortality: while the ratio of men to women appears to be higher in many nations (107 men to 100 women in China; 111 men to 100 women in Pakistan), it is because more women are allowed to die or are killed. In India alone, Kristof said, by age five girls experience a 50 percent higher mortality rate than boys.

“In much of the world, [gender]discrimination is legal,” said Kristof, “If you don’t have enough food, you starve your daughter and you feed your son. If a son is sick, you get a doctor; if your daughter is sick, you feel her forehead and say we’ll see how you do tomorrow.”

And yet, he said, investing in women pays off in both generational and economic capital because women are more likely than men to share earned wealth with their communities and to invest in the well-being of children.

“A dirty little secret is that an awful lot of suffering is caused by bad investment decisions,” said Kristof, who cited statistics showing that in some countries male-controlled household spending results in only two percent of income going to education, compared to 20 percent on disposable items such as alcohol, tobacco or prostitution.

An increase in both education and in microlending to women in developing nations, he said, is already helping fight poverty and discriminatory practices.

“The greatest unexploited resources that poor countries have aren’t gold or diamond mines,” he said. “It’s their female population and female enterprise.”

Following the event, the authors chatted with attendees and signed copies of their books, which had been purchased and donated in advance for students by James Leitner (LAW, ’82).

Kristof and WuDunn received a Pulitzer Prize for international reporting in 1990 for their coverage of student protests in China’s Tiananmen Square. Kristof received a second Pulitzer in 2006 for his New York Times columns.

]]>

The book traces the life and career of the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist, famous for his World War II cartoons featuring the archetypal soldiers “Willie” and “Joe.” Their experiences of infantry life on the field were followed by millions of Americans during the war. Mauldin himself served in the 45th Infantry Division, drawing six cartoons a week for Stars and Stripes while on his tour of duty. At age 23, he was awarded the Pulitzer in 1945 for his collection from the front lines, Up Front, and he received the award again in 1959 for his editorial cartoons.

The Sperber award is given annually by Fordham to an author of a biography or autobiography of a journalist or other media figure. The award was established by a gift from Liselotte Sperber, in memory of her daughter Ann M. Sperber, who wrote the Pulitzer Prize-nominated biography of Edward R. Murrow, Murrow: His Life and Times (Fordham University Press, 1998).

Al Auster, Ph.D., associate professor of media and communications and one of six judges, called DePastino’s book “a superb biography and welcome addition to the literature of how political cartooning has developed in the United States.”

DePastino will receive the award on Nov. 23 at 6:30 p.m. in the 12th Floor Lounge of Lowenstein center, Lincoln Center campus.

Previous recipients of the award include Victor Navasky, Arthur Gelb, Myra MacPherson and David Nasaw.

]]>

“It takes me a long time to produce anything,” Diaz said on April 15 at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus. “It takes me two to three years to write a short story. If I were a quitter, I wouldn’t be doing this.”

Born in the Dominican Republic and raised in Parlin, N.J., Diaz immersed himself in books from a young age. Later, he worked full time at a steel plant to support his studies at Rutgers University.

“It gave me strength of character,” said Diaz, an associate professor of writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “Going to school and working a very physically demanding job made me realize, ‘If I can do this, I’m capable of almost anything.'”

That includes winning the nation’s most-esteemed writing award.

Diaz, who is the author of the critically acclaimed short story collection, Drown(Riverhead, 1996), went on to pen The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (Riverhead, 2007), which won the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

Wao is an epic love story narrated by Yunior de Las Casas, the protagonist of Drown. It chronicles the life of Oscar Cabral, an overweight and atypical Dominican boy growing up in Paterson, N.J., obsessed with science fiction and fantasy novels and with falling in love. The book tells the story of a curse that has plagued Oscar’s family for generations, and life in the Caribbean since colonization and slavery.

The novel also deals heavily with the lives of Oscar’s runaway sister, Lola, his mother, Hypatia “Belicia” Cabral, and his grandfather, Abelard, under the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo, who fiercely ruled the Dominican Republic from 1930 until his assassination in 1961.

So what kind of feedback did Diaz get from Dominicans, or any Latino group for that matter?

“I’ve been called a genius, a fraud and a token,” Diaz said, “but none of it matters.”

“You don’t do this because approval is important to you,” he said. “As an artist, approval is a way to deform your art.”

That is why Diaz chose to write a novel as opposed to non-fiction, even though Oscar Wao is rife with scathing editorials about the way Trujillo, also known as “El Jefe,” ruled the island.

“Don’t think any part of this novel is biographical. It’s a completely made up book,” he said. “When the novel works, it creates a profound relation between the reader and material. It’s the power of art.”

Diaz said he wrote the novel because he felt it needed to be written.

“We’re talking about a traumatized society, the Dominican Republic,” he said. “For the most part, the conversation is just not being had. You really think that the elite wants anyone to do an accounting about who did what to whom during all of those years? Societies are poorly organized to have the will to confront their greatest wounds.”

Though the novel touches profoundly on the struggle Dominican people had on the island, and as immigrants who came to the United States en masse beginning in the 1960s, Diaz is careful to point out that his work will not “explain Dominicans.”

“Nor will it ever attempt to,” he said. “It’s an attempt to explain one made up life.”

Diaz’ talk was sponsored by the creative writing program in the Department of English. Hosted by Daniel Contreras, Ph.D., assistant professor of English, Diaz also gave a reading and lecture at Fordham’s Rose Hill campus on April 15.

]]>DATE: WEDNESDAY, JUNE 13

TIME: 6:30 P.M. COCKTAILS, 7:15 P.M. AWARDS

PLACE: MCNALLY AMPHITHEATRE

LINCOLN CENTER CAMPUS

140 W. 62nd ST., NEW YORK, N.Y.

This year the Blackboard Awards sponsors pay tribute to city teachers who make all the difference in their students’ lives. Award winners are chosen by polling parents, students and educators, and by soliciting nominations via the Blackboard Awards website. Manhattan Media created the awards in 2002 to highlight notable achievements by schools across all of New York’s educational systems.

McCourt, the evening’s master of ceremonies, is the author ofAngela’s Ashes (Harper Perennial, 2005) and Teacher Man (Simon & Schuster, 2005), and taught for 27 years in New York City public schools. Angela’s Ashes won the National Book Critics Circle Award, theLos Angeles Times Book Award, the ABBY Award and the Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

Manhattan Media publishes the community newspapers Our Town, Our Town Downtown, City Hall, The West Side Spirit, Chelsea Clinton News and The Westsider. In addition to Manhattan Media and Fordham University, the Blackboard Awards for Teachers are co-sponsored by BrainPOP, the City University of New York, the United Federation of Teachers and World-Wide Holdings.

For more information on the awards, contact Stephanie Musso at (212) 894-5441,[email protected], or visit www.blackboardawards.com.

]]>White, an English major at Fordham, previously appeared in a production of Wendy Wasserstein’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play,The Heidi Chronicles. White had a supporting role on the ABC sitcom Grace Under Fire, and has had guest appearances on a number of television shows, including HBO’s Six Feet Under, NBC’s Law & Order: Special Victims Unit and ABC’s Desperate Housewives.

Kennedy received the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for Ironweed(Viking, 1983), one of his “Albany Cycle” of novels inspired by his upstate birthplace and current home. The authors will participate in a panel discussion moderated by George W. Hunt, S.J., director of Fordham’s Archbishop Hughes Institute of Religion and Culture, and former editor-in-chief of America magazine.

The Russo lecture series is sponsored by the insititute, through an endowment created by Dr. and Mrs. Robert D. Russo, Sr., (FCRH ’39) and Dr. and Mrs. Robert D. Russo Jr. (FCRH ’69).

Sister Prejean cited polls that show a decline in support for the death penalty and pointed to the re-examination of capital punishment laws in New Mexico, New Jersey and New York, as evidence of the nation’s changing views.

“It is not a moral peripheral issue; it’s at the heart of our society,” said Sister Prejean. “We have to look at our society [and ask]what kind of justice is this … what kind of healing is this?”

Sister Prejean came face to face with those questions while serving as the spiritual adviser during the early 1980s to Patrick Sonnier, a death-row inmate in Louisiana. Since then, she has made it her life’s mission to speak out about what she saw and felt the night of his execution in hopes of convincing others to work for the abolition of the death penalty. In 1993, she published Dead Man Walking , a firsthand account of her experiences with Sonnier while he was on death row.

“A book is a special way of having discourse,” said Sister Prejean. “You’re using your imagination and emotions to take a spiritual journey to get closer to the issue.”

That spiritual journey led Sister Prejean into collaboration with Tim Robbins, who in 1995 wrote and directed a major motion picture based on her book. The film version of Dead Man Walking garnered several Academy Award nominations, and Susan Sarandon won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her portrayal of Sister Prejean.

“It’s all about the discourse,” said Sister Prejean, noting that 1.3 billion people watched Sarandon receive her award and that the book became a national bestseller after the movie was released.

Sister Prejean’s visit to Fordham coincided with the Fordham University theatre department’s production of Tim Robbins’ new theatrical adaptation of Dead Man Walking . The production was part of a yearlong project whereby Robbins invited select schools throughout the United States to stage the play. Sister Prejean and Robbins attended the April 23 performance in Pope Auditorium and later spoke with the cast and crew.

“Anyone performing this play will be reflecting on the issue of the death penalty, and anyone seeing it performed will also be reflecting on it,” said Sister Prejean.

Connor Murphy, a Fordham College at Rose Hill freshman and a member of the Progressive Students for Justice’s prison reform committee, said he felt more confident talking about the complex moral and legal issues surrounding capital punishment after attending Sister Prejean’s lecture and later meeting with her.

“My views against the death penalty are as firm as they have ever been,” he said. “But now I feel less isolated in trying to address the issue.”

]]>