“Here you have on display the greatness of Fordham,” Father McShane said at the June 4 induction ceremony, part of the 2022 Jubilee reunion festivities. “This is something that Fordham rejoices in.”

Turning to the inductees, he added: “We will point to you when we want to tell students who we want them to imitate, what we want them to become.”

Established in 2008, the Hall of Honor recognizes members of the Fordham community who have exemplified and brought recognition to the ideals to which the University is devoted. The 2022 inductees are

- Reginald Brewster, LAW ’50, a Tuskegee Airman and World War II veteran who fought against racism and inequality, earning a Fordham Law degree after the war and practicing civil law for six decades

- Elizabeth A. Johnson, C.S.J., one of the world’s most prominent and influential Catholic theologians, who served as a distinguished professor of theology at Fordham for 27 years and is a former president of the Catholic Theological Society of America

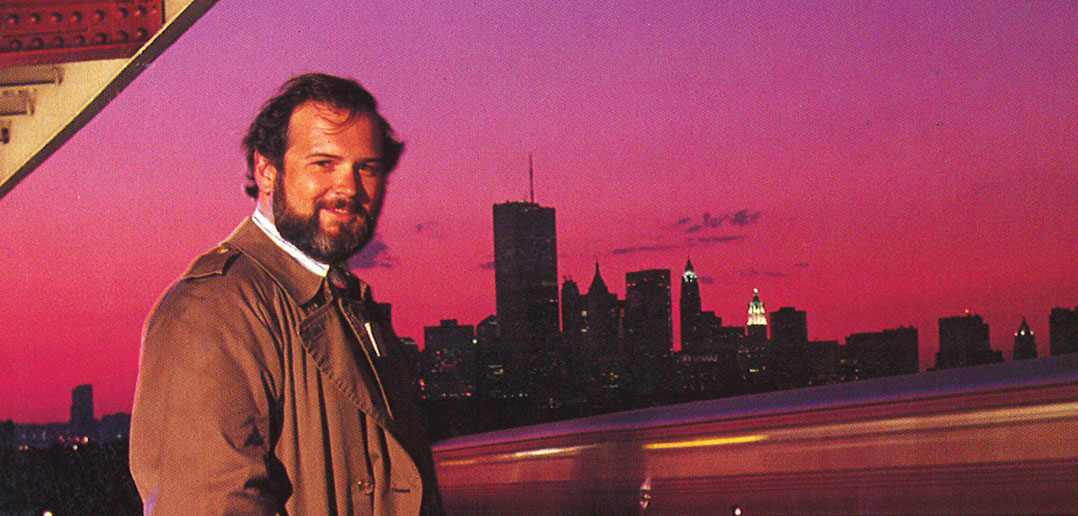

- Jim Dwyer, FCRH ’79, a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who through his writing was both a critical conscience of New York City and a passionate celebrant of its residents, skilled at drawing public attention to wrongful convictions and the mistreatment of society’s most marginalized people

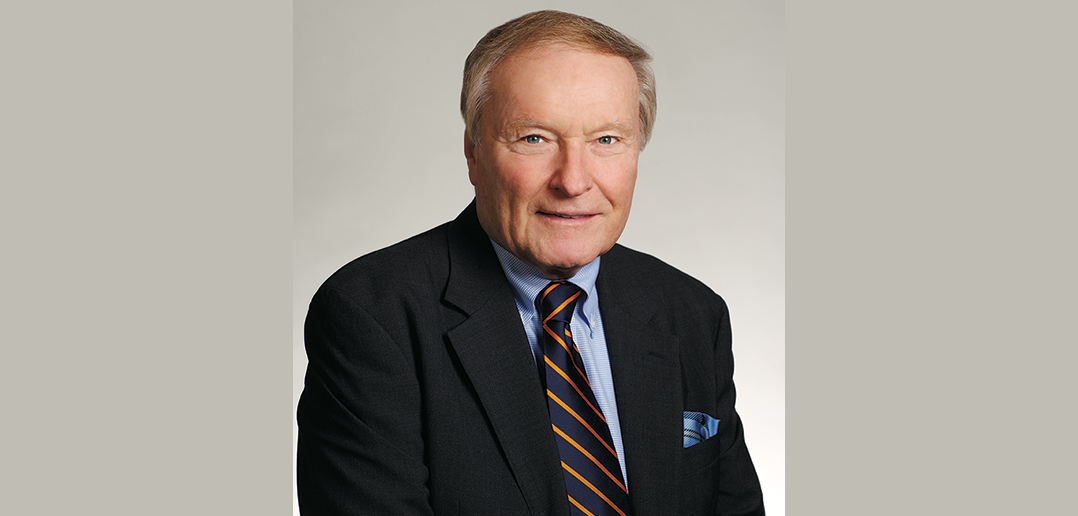

- Herb Granath, FCRH ’54, GSAS ’55, a former Fordham trustee and an Emmy Award-winning ABC executive who helped guide the television network’s expansion, developing flagship stations including ESPN and the History Channel

- Jack Keane, GABELLI ’66, a retired four-star general, former vice chief of staff of the U.S. Army, and 2020 recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, who began his military career as an ROTC cadet at Fordham

- Joe Moglia, FCRH ’71, who has excelled in business and football, as CEO and chairman of TD Ameritrade and as head football coach at Coastal Carolina University, where he currently serves as the executive director for football and executive advisor to the president

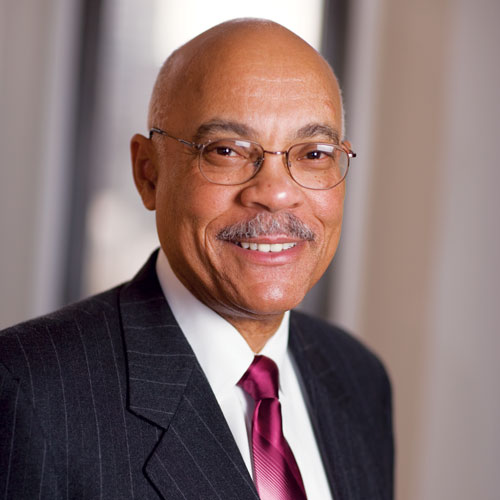

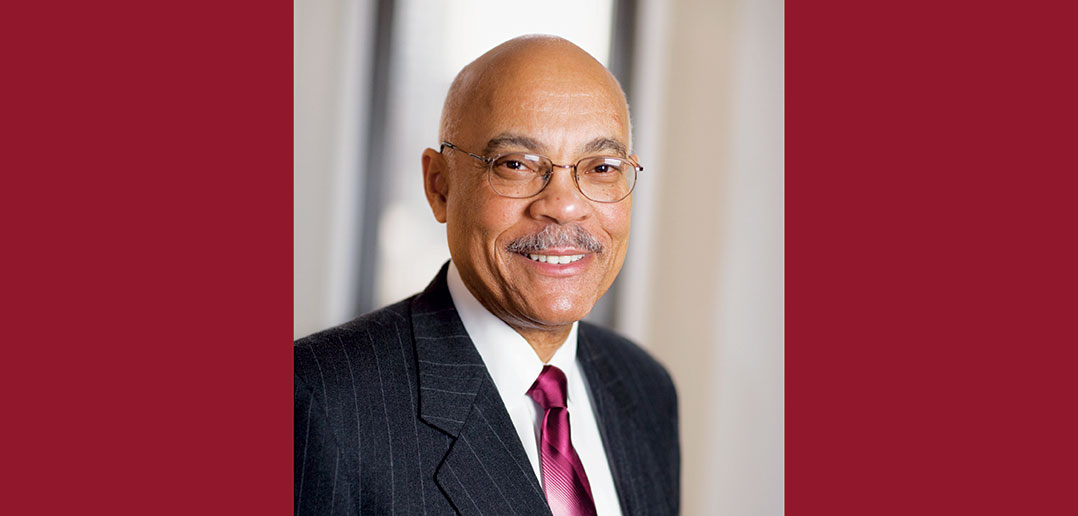

- Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., a decorated Vietnam War veteran and pioneer in the field of social work who served for 13 years, from 2000 to 2013, as dean of Fordham’s Graduate School of Social Service

“This year’s class, each person that has been inducted, represents really the best about Fordham, and they enrich Fordham,” Father McShane said. “Think about it. Very, very diverse backgrounds, very diverse interests. Excellence in all things.”

Three of the inductees—Brewster, Dwyer, and Granath—were honored posthumously at the ceremony, which took place on the lawn outside of Cunniffe House, the Rose Hill home of the Hall of Honor.

Sister Johnson, who retired from the Fordham faculty in 2018, said returning to Rose Hill to be honored at Jubilee felt “awesome, humbling, and beyond imagination.”

Father McShane called her the “most important feminist pioneer theologian in the United States.”

“She changed the way in which we thought about God, and therefore the way we can encounter God,” he said. “I said years ago, when she was honored before, that she dances with questions and she delights in the dance, and she teaches her students to do the same.”

Father McShane described Moglia as someone who “takes great delight in shattering expectations and stereotypes.”

“He is as much at home on the gridiron as he is in the boardroom, and that says a lot,” he said, calling him “a natural-born leader” who “leads with authority.”

The honor put Moglia in an especially select group: He is now only the fourth person in Fordham history—after Wellington Mara, William D. Walsh, and Joseph A. O’Hare, S.J.—to have received the Founder’s Award and been inducted into both the Fordham University Athletics Hall of Fame and the Hall of Honor.

“I give Fordham a lot of credit for any of the things that I’ve done in my life—whether it’s my personal life or professional life, whether as a football coach or in the business world—and so to be ultimately inducted into the Hall of Honor is something that’s very, very special to me,” Moglia said.

Peter Vaughan is “one of my greatest heroes,” Father McShane told the audience, describing him as “ an extraordinarily effective dean” and “a recognized authority that everyone in the profession looked to for wisdom—not only wisdom but heartfelt wisdom, as Peter is somebody who has always balanced heart and mind.”

Speaking of General Keane, Father McShane said that one of his greatest qualities is the care and understanding he has demonstrated for members of the military.

“This man, who was a Fordham ROTC cadet, is looked up to—wisely and rightly—by graduates of West Point, who recognized his wisdom, his courage,” he said.

Father McShane called Dwyer, who died in October 2020 at the age of 63, “the master of the written word” and “the master of his craft.”

“His great gift was seeing the grace and glory and goodness in the moment—the sacrament of the moment and the saint of the moment,” he said. “His last, last columns, they were simply extraordinary because they took the people of the city seriously and raised them to heroic heights, because in Jim’s heart, that’s what they deserved.”

Two of Dwyer’s three brothers, Patrick and Phil, attended the ceremony. For a time in the 1970s, each of them was enrolled at Fordham: Patrick graduated from Fordham College at Rose Hill in 1975 and went on to earn a master’s degree from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences two years later and a Fordham Law degree in 1980. Phil graduated from Fordham College at Rose Hill in 1980, one year after Jim, who was editor-in-chief of The Fordham Ram.

“Fordham was a great experience for all of us—and for Jim especially,” Phil said. “He did so well here, and he continued on to help a lot of people in a lot of different ways, so it’s nice to see that recognized.”

]]>The induction ceremony will be held at Cunniffe House at 5:30 p.m. on Saturday, June 4, just prior to the Jubilee gala.

Established in 2008, the Hall of Honor recognizes members of the Fordham community who have exemplified the ideals to which the University is devoted. This year’s inductees include a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, a world-renowned theologian, and a retired four-star general and recipient of the Medal of Freedom.

Reginald T. Brewster served as a Tuskegee Airman during World War II, a group that included the first Black military aviators in the U.S. Armed Forces. In many ways, the Airmen were fighting two wars, he told Fordham News in 2018: one abroad and one at home. “The discrimination [in the United States] was sharp,” he said. “It was very critical and sometimes it was even hurtful.”

Reginald T. Brewster served as a Tuskegee Airman during World War II, a group that included the first Black military aviators in the U.S. Armed Forces. In many ways, the Airmen were fighting two wars, he told Fordham News in 2018: one abroad and one at home. “The discrimination [in the United States] was sharp,” he said. “It was very critical and sometimes it was even hurtful.”

Upon returning to the U.S., he studied government and math at Fordham College before earning a J.D. from Fordham Law School in 1950 and embarking on a five-decade career as an attorney. When he died in 2020 at the age of 103, the Black Law Students Association at Fordham Law School said that through “his groundbreaking efforts,” he “served as a trailblazer for all Black students who attend Fordham today.”

Sister Elizabeth A. Johnson, C.S.J., who retired in 2018 after 27 years as a distinguished professor at Fordham, is a beloved teacher and one of the most influential Catholic theologians in the world, internationally known for her work in systematic, feminist, and ecological theology, among other fields.

Sister Elizabeth A. Johnson, C.S.J., who retired in 2018 after 27 years as a distinguished professor at Fordham, is a beloved teacher and one of the most influential Catholic theologians in the world, internationally known for her work in systematic, feminist, and ecological theology, among other fields.

In her particularly influential 2007 book, Quest for the Living God: Mapping Frontiers in the Theology of God, she examined how God is understood differently by men, women, poor and oppressed people, Holocaust victims, and people of a variety of faiths. “Faith,” she once said, “is hope that the world is good and that our efforts can make a difference.”

Jim Dwyer, who died in October 2020 at the age of 63, chronicled the life of New York City with conscience and compassion in a four-decade career as a journalist and author. A 1979 graduate of Fordham College at Rose Hill, he sought to tell the stories of everyday New Yorkers and give voice to those on society’s margins, including working-class immigrants, racial and ethnic minorities, and people convicted of crimes they did not commit.

Jim Dwyer, who died in October 2020 at the age of 63, chronicled the life of New York City with conscience and compassion in a four-decade career as a journalist and author. A 1979 graduate of Fordham College at Rose Hill, he sought to tell the stories of everyday New Yorkers and give voice to those on society’s margins, including working-class immigrants, racial and ethnic minorities, and people convicted of crimes they did not commit.

Through his reporting and writing—for New York Newsday, the Daily News, and The New York Times—he worked to help the public understand the impact of major issues and events, most notably 9/11, as well as the inner workings of government agencies and how their decisions affect people’s lives. He won two Pulitzer Prizes for his work and was widely regarded as a generous colleague, friend, and mentor.

Herb Granath, a two-time Fordham graduate and trustee emeritus, was a pioneering force in cable television. A former president of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, he started his career as an NBC page while he studying physics at Fordham. After graduating in 1954, he enrolled at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, earning a master’s degree in communication arts one year later. He steadily climbed the ranks of entertainment juggernauts, moving from NBC to ABC to ESPN and the Broadway stage. He became chairman of the board of ESPN after ABC purchased the cable channel in 1984, and he was responsible for the creation of several channels that are now household names, including A&E, the History Channel, Lifetime, and the Hallmark Channel.

Herb Granath, a two-time Fordham graduate and trustee emeritus, was a pioneering force in cable television. A former president of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, he started his career as an NBC page while he studying physics at Fordham. After graduating in 1954, he enrolled at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, earning a master’s degree in communication arts one year later. He steadily climbed the ranks of entertainment juggernauts, moving from NBC to ABC to ESPN and the Broadway stage. He became chairman of the board of ESPN after ABC purchased the cable channel in 1984, and he was responsible for the creation of several channels that are now household names, including A&E, the History Channel, Lifetime, and the Hallmark Channel.

Granath, who died in November 2019 at the age of 91, earned numerous awards, including two Tonys, an Emmy for lifetime achievement in international TV, and an Emmy for lifetime achievement in sports. He often spoke about the value of his Fordham education, noting that a course in logic was among the most influential he ever took. “It is amazing to me in American business how little a role logic plays,” he told Fordham Magazine in 2007. “It has been a hallmark of the way I approach business.”

Jack Keane, a retired four-star general and former vice chief of staff of the U.S. Army, grew up in a housing project on Manhattan’s Lower East Side and was the first member of his family to attend college. He began his military career at Fordham as a cadet in the University’s ROTC program. After graduating in 1966 with a bachelor’s degree in accounting, he served as a platoon leader and company commander during the Vietnam War, where he was decorated for valor. A career paratrooper, he rose to command the 101st Airborne Division and the 18th Airborne Corps before he was named vice chief of staff of the Army in 1999.

Jack Keane, a retired four-star general and former vice chief of staff of the U.S. Army, grew up in a housing project on Manhattan’s Lower East Side and was the first member of his family to attend college. He began his military career at Fordham as a cadet in the University’s ROTC program. After graduating in 1966 with a bachelor’s degree in accounting, he served as a platoon leader and company commander during the Vietnam War, where he was decorated for valor. A career paratrooper, he rose to command the 101st Airborne Division and the 18th Airborne Corps before he was named vice chief of staff of the Army in 1999.

Since retiring from the military in 2003, Keane has been an influential adviser, often testifying before Congress on matters of foreign policy and national security. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2020, becoming the sixth Fordham graduate to receive the nation’s highest civilian honor. In a 2017 interview with Fordham Magazine, he described the Jesuit education he received at Fordham as a transformational experience. “The whole learning process was about your own growth and development as a human being—not just intellectually but also morally and emotionally. I don’t think I would have been as successful as a military officer if my path didn’t go through Fordham University.”

Joe Moglia coached both high school and college football after graduating from Fordham College at Rose Hill in 1971, but in 1984, the New York native made a career change to finance, blazing a trail of ascent at Merrill Lynch and then at the helm of TD Ameritrade over 24 years. He returned to coaching in 2009, finishing his career with six seasons as the head coach at Coastal Carolina University, where he led the team to a 56-22 cumulative record and three Big South Conference titles before stepping down in 2019.

Joe Moglia coached both high school and college football after graduating from Fordham College at Rose Hill in 1971, but in 1984, the New York native made a career change to finance, blazing a trail of ascent at Merrill Lynch and then at the helm of TD Ameritrade over 24 years. He returned to coaching in 2009, finishing his career with six seasons as the head coach at Coastal Carolina University, where he led the team to a 56-22 cumulative record and three Big South Conference titles before stepping down in 2019.

He is currently executive director for football and executive advisor to the president at Coastal Carolina and is chairman of Fundamental Global and Capital Wealth Advisors. Last year, he was inducted into the Fordham Athletic Hall of Fame, and in November, he was honored with a Fordham Founder’s Award. His career is the subject of the 2012 book by Monte Burke titled 4th & Goal: One Man’s Quest to Recapture His Dream. And Moglia has authored books on both coaching and investing—The Perimeter Attack Offense: The Key to Winning Football in 1982 and Coach Yourself to Success: Winning the Investment Game in 2005.

Peter B. Vaughan, Ph.D., served as dean of Fordham’s Graduate School of Social Service for 13 years. When he stepped down in 2013, he received the President’s Medal for “his collaborative and visionary leadership as an educator, and for his lasting impact on the University’s ability to lead well and serve wisely in the years ahead.”

Peter B. Vaughan, Ph.D., served as dean of Fordham’s Graduate School of Social Service for 13 years. When he stepped down in 2013, he received the President’s Medal for “his collaborative and visionary leadership as an educator, and for his lasting impact on the University’s ability to lead well and serve wisely in the years ahead.”

Vaughan’s distinguished social work career is rooted in his undergraduate days at Temple University, when during the civil rights movement he was involved in court watching and voter registration efforts. He later served in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War and found himself tending to the mental health needs of soldiers on the front lines. For much of his career, Vaughan worked with communities of color, focusing especially on the health of African American boys. He was a professor at Wayne State University in Detroit and later became acting dean of the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Work before he came to Fordham.

In 2012, the National Association of Social Workers presented him with its Knee/Wittman Lifetime Achievement Award. “Ours is a profession of hope, and I never miss a chance to pass it on to students when I am able to,” Vaughan told Fordham graduates at the Graduate School of Social Service diploma ceremony in 2013. “As you leave today to begin meaningful and illustrious careers, I hope you will live every day to make the world a better place—and keep hope alive.”

Jubilee 2022 will be held on the Rose Hill campus from June 3 to 5. Learn more and register today.

]]>Rose Hill

Tuesday, March 8 at 4:30 p.m. in Tognino Hall, Duane Library

Wednesday, March 9 at 10 a.m. in the Campbell Hall Multipurpose Room

Lincoln Center

Thursday, March 10 at 12:30 p.m. in the 12th-Floor Lounge, Lowenstein Center

(The Task Force will also schedule a meeting at the Westchester campus in the coming weeks.)

At the meetings, members of the Task Force will discuss the charge of the group, how it will proceed, and answer some questions about the group.

The Task Force members would like to gather your questions and comments prior to the meetings. Kindly submit your questions and comments online (due to time constraints, not all questions may be addressed).

If you would like to share further (or more detailed) feedback, you may also email [email protected].

]]>“If you strip away the pieces of fundraising that are industry specific, at the end of the day it boils down to how well you communicate what you are doing,” said Lauri Goldkind, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS). “If can’t communicate why your program is special, then it is sunk.”

Communications, public relations, and fundraising have become an integral component of executive leadership at human services organizations (HSOs). In his final lecture at Fordham as dean of GSS, Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., reiterated the need for leaders to sharpen their communication skills.

“Simply put, we are challenged by bad press,” he said.

The field’s relatively recent emphasis on communication takes place amid an increasingly competitive race for philanthropic dollars and a revolution in communications, particularly as it relates to social media. Goldkind’s most recent scholarship hones in on how executives utilize social media to change policy and raise money.

To conduct the study, Goldkind received a faculty research grant from the University, which eventually led to a two-year grant from the Kresge Foundation in partnership with the Center for Philanthropy at Indiana University. Both organizations are interested in civic engagement issues. In order to understand how human service organizations use electronic media to promote policy change and raise funds, Goldkind surveyed 260 human service organizations and collected data from 25 executive leaders.

In her project summery, Goldkind wrote that HSOs have been slow to adapt to technological advances, yet increasingly an organization’s survival depends on a leader’s ability to adapt to evolving technological strategies.

Even though the data is still being analyzed, a few trends have emerged on how effective electronic outreach works. Goldkind has found that the way leaders think about social media dictates how efficiently it gets used and that the most successful executives delegate their social media profile. Successful use of Twitter alone requires constant use, which requires time your average HSO director does not have. To properly exploit the media, executives must hand over their “voice” to someone else.

Goldkind cited one of the more sophisticated media users from her survey who told her that while he prioritizes high-quality writing, if he wanted his staff to fully engage with the agency’s constituency, then he needed “to loosen the reigns a little bit.”

Another communication challenge facing HSO executives is that their constituencies may not necessarily relate to them. In a soon-to-be-published article in Advances in Social Work, titled “Social Workers as Senior Executives: Does Academic Training Dictate Leadership Style,” Goldkind cited literature that found that 82 percent of the nonprofit executive directors were white, even though the organizations primarily serve people of color.

Further distancing HSO executives from the people they serve is that when leadership positions need to be filled, business experience often trumps on-the-ground experience.

“The perception among people who are hiring those leaders is that social workers don’t have the financial chops to run organizations,” said Goldkind.

Nevertheless, Goldkind found only marginal differences between social workers and leaders from different disciplines; yet few make it to the boardroom. Despite the lack of advancement, Goldkind said that academic training often skews toward clinical roles rather than administrative.

“If you are in an agency setting and you want to be a senior leader, you’re competing against a J.D., an M.B.A., or you’re competing against a master of public administration,” said Goldkind. “Social workers will need to have a place at the table in an economic context and policy context if they’re really going to make a difference.”

There remains a schism within the profession, she said, with many social workers skeptical of the emphasis on leadership and philanthropy. Most students come to the profession with a sense of mission, seeing themselves as hands-on social workers rather than administrators.

“If social work is about change, then we need to move away from an individual-level change model to an agency change, to a community change, and expand the scope of what that change should look like,” she said.

Goldkind argued that today’s social work student should leave the university understanding how to recruit and retain talent, how financial resources flow through an agency, how to evaluate their program, how to write grants, and how to fundraise.

The tide may be changing, however. Goldkind’s course, Leadership and Macro Practice, has been filled, and GSS has partnered with the Graduate School of Business Administration to offer a master of science in nonprofit leadership.

]]>

Photo by Michael Dames

In his outgoing lecture, Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., the dean of the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS) outlined two significant challenges facing the field of social work: enhancing public relations and creating diversity within the ranks.

“Simply put, we are challenged by bad press,” said Vaughan, who will retire this summer after serving more than a decade as GSS dean.

He said that both the taxpaying public and the recipients of services tend to be critical of the often-unenviable work of social workers. Taxpayers resent having to help those who have “not met the self-sufficiency criterion of what many consider the American ‘ideal.’” And clients resent having to be told how to best handle their social problems.

“In other words, social workers frequently represent an unpopular cause for unpopular people,” he said.

This uphill public relations battle is exacerbated each time a child in the child welfare system is hurt, whenever a parolee commits a crime, or whenever a patient with dementia wanders away from a mental health facility. Such bad press allows others to define the profession—a task that Vaughan argued should be owned by the social workers themselves.

“We cannot and must not leave the telling of our stories to others,” he said. And while client confidentiality must remain a priority, holding back stories of the good work of social workers means that the importance of the work can be minimized or distorted by others.

On diversity, Vaughan said that it is integral to “ensure that each of us is welcome to eat at the table of good will.” He explained the importance of “starting where the client is,” adding that workers must be physically and psychologically available to those seeking help; thus, the workforce should reflect client diversity.

“If inclusion of a diverse staff and management that reflects the buying public makes business sense to Macy’s, then it should make good business sense in social service organizations,” he said.

For those who claim that hiring a diverse well-trained staff is impossible, Vaughan argued that sufficient support is needed to mine diverse talent. If that talent can’t be found, it should be cultivated through “resources to look for them.”

After more than a decade at the helm at GSS, Vaughan recalled the early days of his own career when he was still “one of those in-your-face-do-gooders.”

“I was convinced, as I stood beside the reflecting pool of the Lincoln Memorial on a hot August day in 1963 and listening to the speeches about hope, that I could make a difference for the common good as a member of the social work profession,” he said. “I still believe deeply in the good work we do and in our potential to do even more.”

Under Vaughan’s decade of leadership, the GSS has increased its focus on human rights and social justice in its curriculum and has risen in college ranks to its current place of 11th in U.S. News & World Report for graduate schools of social work. It is Fordham’s highest-ranking school.

Dean Vaughan Receives Fordham’s Highest Honor

Fordham University bestowed its highest honor, the President’s Medal, on Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., outgoing dean of the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS).

Fordham University bestowed its highest honor, the President’s Medal, on Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., outgoing dean of the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS).

Joseph M. McShane, S.J. president of Fordham, presented Vaughan with the medal at the GSS diploma ceremony on May 20, calling him a “wise, patient, and loving patron saint.”

Admitting that the day was a bittersweet one, GSS faculty and administrators lauded Vaughan for his exceptional service to the school. Under Vaughan’s tenure, GSS jumped to No. 11 in U.S. News & World Report national rankings, the highest in the school’s history. Its online MSW program is ranked No. 1 in the nation.

“These achievements are primarily due to Peter,” said Sandra G. Turner, Ph.D., associate dean of GSS. “He is a visionary. He has always looked at what could be rather than what is.”

-Joanna Klimaski

]]>

In his outgoing lecture, Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., the dean of the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS) outlined two significant challenges facing the field of social work: enhancing public relations and creating diversity within the ranks.

“Simply put, we are challenged by bad press,” said Vaughan, who will retire this summer after serving more than a decade as GSS dean.

He said that both the taxpaying public and the recipients of services tend to be critical of the often-unenviable work of social workers. Taxpayers resent having to help those who have “not met the self-sufficiency criterion of what many consider the American ‘ideal.’” And clients resent having to be told how to best handle their social problems.

“In other words, social workers frequently represent an unpopular cause for unpopular people,” he said.

This uphill public relations battle is exacerbated each time a child in the child welfare system is hurt, whenever a parolee commits a crime, or whenever a patient with dementia wanders away from a mental health facility. Such bad press allows others to define the profession—a task that Vaughan argued should be owned by the social workers themselves.

“We cannot and must not leave the telling of our stories to others,” he said. And while client confidentiality must remain a priority, holding back stories of the good work of social workers means that the importance of the work can be minimized or distorted by others.

On diversity, Vaughan said that it is integral to “ensure that each of us is welcome to eat at the table of good will.” He explained the importance of “starting where the client is,” adding that workers must be physically and psychologically available to those seeking help; thus, the workforce should reflect client diversity.

“If inclusion of a diverse staff and management that reflects the buying public makes business sense to Macy’s, then it should make good business sense in social service organizations,” he said.

For those who claim that hiring a diverse well-trained staff is impossible, Vaughan argued that sufficient support is needed to mine diverse talent. If that talent can’t be found, it should be cultivated through “resources to look for them.”

After more than a decade at the helm at GSS, Vaughan recalled the early days of his own career when he was still “one of those in-your-face-do-gooders.”

“I was convinced, as I stood beside the reflecting pool of the Lincoln Memorial on a hot August day in 1963 and listening to the speeches about hope, that I could make a difference for the common good as a member of the social work profession,” he said. “I still believe deeply in the good work we do and in our potential to do even more.”

Under Vaughan’s decade of leadership, the GSS has increased its focus on human rights and social justice in its curriculum and has risen in college ranks to its current place of 11th in U.S. News & World Report for graduate schools of social work. It is Fordham’s highest-ranking school.

Dean Vaughan Receives Fordham’s Highest Honor

Fordham University bestowed its highest honor, the President’s Medal, on Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., outgoing dean of the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS).

Joseph M. McShane, S.J. president of Fordham, presented Vaughan with the medal at the GSS diploma ceremony on May 20, calling him a “wise, patient, and loving patron saint.”

Admitting that the day was a bittersweet one, GSS faculty and administrators lauded Vaughan for his exceptional service to the school. Under Vaughan’s tenure, GSS jumped to No. 11 in U.S. News & World Report national rankings, the highest in the school’s history. Its online MSW program is ranked No. 1 in the nation.

“These achievements are primarily due to Peter,” said Sandra G. Turner, Ph.D., associate dean of GSS. “He is a visionary. He has always looked at what could be rather than what is.”

]]>

Fordham University has bestowed its highest honor, the prestigious President’s Medal, on Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., outgoing dean of the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS). Vaughan is retiring after 13 years as dean.

Joseph M. McShane, S.J. president of Fordham, presented Vaughan with the medal at the GSS diploma ceremony on May 20, calling him a “wise, patient, and loving patron saint.”

Faculty and administrators of GSS lauded Vaughan for his exceptional service to the school, admitting that the day was a bittersweet one for GSS. Under Vaughan’s tenure, GSS jumped to No. 11 in U.S. News & World Report national rankings, the highest in the school’s history. Its online MSW program is ranked No. 1 in the nation.

“These achievements are primarily due to Peter,” said Sandra G. Turner, Ph.D., associate dean of GSS. “He is a visionary. He has always looked at what could be rather than what is.”

Vaughan’s distinguished social work career is rooted in his undergraduate days at Temple University, when during the Civil Rights movement he was involved in court watching and voter registration efforts. He later served in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War and found himself tending to the mental health needs of soldiers on the front lines.

For much of his career, Vaughan worked with communities of color, focusing especially on the health of African-American boys. He was a professor at Wayne State University in Detroit and later became acting dean of the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Work before he came to Fordham.

In 2012, the National Association of Social Workers presented him with its Knee/Wittman Lifetime Achievement Award.

“Ours is a profession of hope, and I never miss a chance to pass it on to students when I am able to,” Vaughan said at the GSS diploma ceremony, for which he served as commencement speaker.

“As you leave today to begin meaningful and illustrious careers, I hope you will live every day to make the world a better place—and keep hope alive.”

The President’s Medal is the highest honor that a president can bestow. Past recipients of the medal include the late Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., the former Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society at Fordham.

Founded in 1841, Fordham is the Jesuit University of New York, offering exceptional education distinguished by the Jesuit tradition to more than 15,100 students in its four undergraduate colleges and its six graduate and professional schools. It has residential campuses in the Bronx and Manhattan, a campus in West Harrison, N.Y., the Louis Calder Center Biological Field Station in Armonk, N.Y., and the London Centre at Heythrop College, University of London, in the United Kingdom.

]]>

In his outgoing lecture, Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., the dean of the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS) outlined two significant challenges facing the field of social work: enhancing public relations and creating diversity within the ranks.

“Simply put, we are challenged by bad press,” said Vaughan, who will retire this summer after serving more than a decade as GSS dean.

He said that both the taxpaying public and the recipients of services tend to be critical of the often-unenviable work of social workers. Taxpayers resent having to help those who have “not met the self-sufficiency criterion of what many consider the American ‘ideal.'” And clients resent having to be told how to best handle their social problems.

“In other words, social workers frequently represent an unpopular cause for unpopular people,” he said.

This uphill public relations battle is exacerbated each time a child in the child welfare system is hurt, whenever a parolee commits a crime, or whenever a patient with dementia wanders away from a mental health facility. Such bad press allows others to define the profession—a task that Vaughan argued should be owned by the social workers themselves.

“We cannot and must not leave the telling of our stories to others,” he said. And while client confidentiality must remain a priority, holding back stories of the good work of social workers means that the importance of the work can be minimized or distorted by others.

On diversity, Vaughan said that it is integral to “ensure that each of us is welcome to eat at the table of good will.” He explained the importance of “starting where the client is,” adding that workers must be physically and psychologically available to those seeking help; thus, the workforce should be reflective of client diversity.

“If inclusion of a diverse staff and management that reflects the buying public makes business sense to Macy’s, then it should make good business sense in social service organizations,” he said.

For those who claim that hiring a diverse well-trained staff is impossible, Vaughan argued that sufficient support is needed to mine diverse talent. If that talent can’t be found, it should be cultivated through “resources to look for them.”

After more than a decade at the helm at GSS, Vaughan recalled the early days of his own career when he was still “one of those in-your-face-do-gooders.”

“I was convinced, as I stood beside the reflecting pool of the Lincoln Memorial on a hot August day in 1963 and listening to the speeches about hope, that I could make a difference for the common good as a member of the social work profession,” he said. “I still believe deeply in the good work we do and in our potential to do even more.”

Under Vaughan’s decade of leadership, the GSS has increased its focus on human rights and social justice in its curriculum and has risen in college ranks to its current place of 11th in U.S. News & World Report for graduate schools of social work. It is Fordham’s highest-ranking school.

]]> Fordham University has announced the appointment of Debra M. McPhee, Ph.D., as the new dean of the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS). She will replace Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., who will retire at the end of this academic year.

Fordham University has announced the appointment of Debra M. McPhee, Ph.D., as the new dean of the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS). She will replace Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., who will retire at the end of this academic year.

McPhee brings extensive professional experience to her new post, having served for more than a decade in various clinical, academic, and administrative roles. She worked for the last two years as chief operating officer for the Palo Alto-based Planet Hope/Liiv.com, a firm that specializes in online health education and technology.

From 2005 to 2010, McPhee was dean of the School of Social Work at Barry University in Miami Shores, Fla. Before becoming dean, McPhee served for three years as associate dean and had been a faculty member since 1997. An award-winning educator, she taught a variety of courses, from introductory social work practice at the undergraduate level to graduate courses on social policy issues in family and children’s services.

She earned her doctorate in 1998 from the Faculty of Social Work at the University of Toronto, her master’s degree from the School of Social Work at Columbia University in 1989, and a bachelor’s degree in psychology from St. Mary’s University in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1986.

Her primary areas of research, in which she has published widely, include international health care policy, child abuse and neglect, women and welfare reform, public policy analysis, and professional practice and service delivery.

“In Debra, we have an outstanding new dean who is committed to working closely with the faculty, students, and staff of the Graduate School of Social Service. Together, they will sustain and advance the school’s long tradition of national preeminence in educating skilled, compassionate social workers to serve the human family,” said Stephen Freedman, Ph.D., provost of the University and professor of ecology and evolutionary biology.

— Joanna Klimaski

]]>Yet the directors of each program are quick to say that what they do is not much helping the problem of hunger.

On May 2, the program directors joined members of the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS) at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus to premiere the documentary Our Daily Bread: Feeding the Hungry in New York City, which was followed by a panel discussion about the film.

Moderated by Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., dean of GSS, the panel featured film director Dale Lindquist, D.Min., managing director of the Beck Institute, and the directors of the three emergency feeding programs featured in the film: Anthony Butler, of St. John’s Bread and Life in Bedford-Stuyvesant; the Rev. Elizabeth G. Maxwell, of Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen in the Chelsea section of Manhattan; and Doreen Wohl, of the West Side Campaign Against Hunger, run out of the Church of St. Paul and St. Anthony in Manhattan.

Each program began with someone knocking on the church doors asking for something to eat, and has since grown to include daily soup kitchens and mobile kitchens, food pantries, and local hubs that connect people with social services.

The fact that they have grown so dramatically, though, is alarming, program directors said. When Lindquist began filming the documentary in 2010, the West Side Campaign Against Hunger fed 34,000 families and provided food for 800,000 meals. Today, Wohl said, the organization serves 45,000 households and provides food for more than 1 million meals.

“I never let a group of volunteers come into [our organization]and leave thinking that we’re the right solution,” Wohl said. “I shock them by saying I think it’s terrible that we have to do this—that it’s not acceptable this day in age.”

Despite their comprehensive outreach efforts, these programs are not enough, Butler said. There must also be a robust political response that can chip away at the real problem, of which hunger is merely a symptom.

“Poverty is the problem, and the answer is justice,” Butler said. “We need to change the conversation. It’s not about throwing a few crumbs at people, or rescuing thrown-away food. There’s plenty of food. What there’s not enough of are jobs or fair housing.”

The solution must come from several angles, said Rev. Maxwell, because poverty is bound up with other national issues, such as an overcrowded prison industry, failing schools, and dwindling access to healthcare.

“It’s about how we spend our resources,” she said. “We need more than the response of the religious community—we need the political will to respond to this crisis.”

In addition to shedding light on the realities of hunger in New York City, Lindquist said that the film is meant to challenge societal prejudices against the poor, for instance, the notion that the poor do not make sufficient efforts to get out of poverty.

“There’s an assumption about who these people are, so I’m hoping this film will change assumptions,” Lindquist said.

The film features several firsthand accounts from visitors to the soup kitchens and food pantries, including a worker in St. John’s Bread and Life program, who had spent 25 years as one of the city’s homeless. One morning, while he was sleeping outside the church, a Bread and Life worker asked if he would like to help in the pantry. He now works as one of the managers.

His story, Lindquist said, is meant to show the inherent dignity of those who are usually the invisible members of society.

“We need to ask, ‘Who is my neighbor? Who is valuable?’ That’s the conversation we need to have,” Butler said.

(Watch a trailer from Our Daily Bread below)

]]>Pope Auditorium | Lowenstein Center | 113 W. 60th St. | New York City

1 in 5 New York City residents uses soup kitchens and food pantries each year.

This 45-minute documentary portrays the ground breaking, innovative work of three faith-based—and largest—emergency food programs in New York City, serving more than one million New Yorkers each year.

Each program began with someone knocking at the door of a neighborhood house of worship.

A panel conversation, moderated by Graduate School of Social Service Dean Peter Vaughan, Ph.D., will follow with the film director and agency directors on what is being done and the work that remains ahead.

For more information, contact Dale Lindquist, D.Min., at 914-367-3438 or [email protected].

]]>