John McDonagh, director of facilities operations at Lincoln Center, said Higgins was a natural-born leader who possessed a broad, expansive knowledge of the construction trades that he eagerly shared with others.

“He always took control of a situation—emergencies, anything. If you had an issue, you called him, and he’d get it taken care of,” he said.

“The guy knew everything from carpentry and plumbing to electrical and welding. His skill set was unrivaled.”

Higgins was born on October 27, 1970, to Tom and Gail Higgins and grew up in the shadow of the Throgs Neck Bridge in the Bronx neighborhood of Silver Beach. He graduated from Monsignor Scanlan High School in Throgs Neck in 1988.

He trained as a plumber and worked in maintenance and facilities positions for Maritime College and Mill Neck Manor School for the Deaf. He came to Fordham in 2016 after two years working as a plumber mechanic for the Hicksville School District in Long Island.

Just three years later, he was honored with a Sursum Corda award at the University’s annual convocation. He was lauded as one of the most valued members of the Facilities Department “because of his energetic approach to sharing his skills and knowledge with his colleagues.”

“Over the past few years, Jimmy has been at the forefront of several significant and unforeseen plumbing incidents, and it was his problem-solving abilities that were instrumental in helping the department in resolving those events,” his citation read.

Higgins met his wife, Christine, a teacher at Mill Neck Manor, while supervising the construction of a new building there. She said she was attracted to him because of his troubleshooting skills, his sense of humor, and his “honest, true love of kids and people.”

“He was a quiet genius when it came to fixing and building anything imaginable,” she said. “He was always kind, always helpful, and went out of his way for others.”

True to his maritime roots, Christine said he enjoyed fishing and relaxing with friends and family on boats, as well as bow hunting. Colleagues might not know that he was also an avid reader, she said.

She said she’d always treasure their time trekking up to a cabin in knee-deep snow in Hancock, New York, listening to Irish music on Sundays on WFUV’s Ceol na nGael, and listening to John Denver.

“He was a mentor to so many people without realizing it,” she said.

McDonagh, who attended high school with Higgins’s older brother Tom, considered him a friend for the past 30 years. He said he will miss the daily morning meetings where they’d discuss how to tackle the pressing project of the day on campus.

“Jimmy was a person who I could walk through campus and bounce technical ideas off of him,” he said.

“In our field, it’s a very precious thing to be able to trust somebody and have these conversations. That is something I’ll miss more than anything. I looked forward to those sessions every day.”

Higgins is survived by his wife, Christine, his first wife Karen, his brother Tom, his sister Ellen, and his children James and Jamie.

A wake will be held on Thursday, Jan. 16, from 3 to 7 p.m. at Schuyler Hill Funeral Home, 3535 E. Tremont Avenue in the Bronx. A funeral Mass will be held on Friday, Jan. 17, at 10 a.m. at St. Frances de Chantel Church, 90 Hollywood Avenue.

]]>In Trevithick’s undergraduate courses, including Taboo: the Anthropology of the Forbidden and Human Sexuality in Cross-Cultural Perspective, he often revealed how similar humans are in their attractions and aversions.

“We exchanged ideas on which courses might appeal to students and what course names would be most appropriate,” said Anthropology Professor Allan S. Gilbert, Ph.D., the department chair at the time of Trevitheck’s hiring in 2007. Since many of Fordham’s anthropology courses were designed in the 1960s and 1970s, they needed to bring the content and terminology up to date in a way that would also attract students. “Alan was very good at that,” said Gilbert. “He was also an excellent teacher and influenced numerous students to major in anthropology over the years.”

Recent graduate Ellen Sweeney, FCRH ‘23, recalled the compelling discussions she had in two of Trevithick’s classes, even through Zoom during the 2020–2021 academic year.

“I always walked out of his classrooms—virtual and in person—with a smile on my face, musing about all that we had discussed,” she said. “I practically re-taught his lectures to my friends because they were so interesting.”

It may have helped that he often taught his remote classes during the pandemic with his blue parrotlet Giuseppe Celestiano DiForpini—Pino for short—on his shoulder. “Seeing his love for the bird and care for teaching us helped me stay engaged during the semester, and I think it helped me stay on track through that whole difficult year,” said Sweeney.

Born on November 11, 1952, in Washington, D.C., Trevithick was raised by parents who inspired his lifelong intellectual curiosity and wanderlust. His father, John Trevithick, worked for the U.S. mission to the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna, where Trevithick spent several of his childhood years. His mother taught high school and college level English.

Trevithick lived abroad again in his 30s, after earning a bachelor’s in history of religion from George Washington University, a master’s in South Asian studies from the University of Wisconsin, and a Ph.D. in social anthropology from Harvard University. His doctoral research brought him to India for two years as a Fulbright Scholar. It culminated in his research monograph about one of the world’s largest pilgrimage sites, Bodh Gaya.

In the 1990s, Trevithick met his wife, Fordham Mathematics Professor Melkana Brakalova-Trevithick, Ph.D., while the two were teaching at the American University in Bulgaria.

“He just fell in love with the country, and appreciated its complex, ancient history and culture. The Bulgarians are very appreciative of intellectual strengths … and of rich creative inner lives.” Trevithick could relate: he was a musician, an artist, and a writer—he later penned a weekly column for a local Connecticut paper he edited, The Voice, and before he died was hard at work on a comic sci-fi novel, Raise the City, which draws from his Cornish heritage that stretches back to the English inventor of the steam locomotive, Richard Trevithick.

“He was always bubbling with creativity and abilities—whether it was playing jazz on the keyboard, creating paper mâché inspired by mathematical fractals, or spending hours writing his book,” his wife said.

At Fordham, he was instrumental in the unionization efforts for adjunct and contingent faculty. He continued his activism through the Unitarian Universalist Congregation, where he served on their Social Justice Committee.

“His kindness, optimism, and intellect were unmatched,” said Brakalova-Trevithick. “Many people say he was one in a million. I am saying one in infinity.”

Trevithick cherished time with his sons, Joe and Alex, sharing in their pursuits, whether fishing in Connecticut lakes or traveling to the Black Sea. In addition to his wife and sons, Trevithick is survived by his brother, John; daughter-in-law, Kelly; granddaughter, Molly; and many other family members and friends.

A celebration of life service will be held on Nov. 24, at 2 p.m. at the Community Unitarian Universalist Congregation in White Plains, New York, with an option to attend via Zoom. For details, please email [email protected]. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to a charity of your choice or to support the publication of Raise the City.

]]>Hoffman was widely respected at Fordham for her interdisciplinary expertise and collaborative spirit.

Elizabeth Stone, Ph.D., a professor of English, said that despite their different fields of study, they grew to be fast friends.

“I always knew we spoke the same language. Decade after decade, our conversations about one another’s work were immensely gratifying,” she said.

Magda Teter, Ph.D., the Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies at Fordham, called Hoffman “a beloved member of Fordham’s Jewish Studies community” and said her work was marked by “great erudition and disciplinary depth.”

“In her 1991 work on the Hebrew writer and Nobel Prize laureate S.Y. Agnon, she deployed a wide range of theoretical tools, ranging from psychoanalysis to feminist theory,” Teter said.

“She placed Agnon in conversation with other writers, such as James Joyce, Kafka, and Thomas Mann. … She was able to handle, with equal care and knowledge, traditional Jewish text and modern philosophy.

Hoffman was born on June 19, 1946, in New York City and grew up, along with her younger brother, David, in Brooklyn. She earned a bachelor’s in English and Comparative Literature from Cornell University and a master’s and Ph.D. in English and Comparative Literature from Columbia University. She was a special member of Columbia’s Association for Psychoanalytic Medicine.

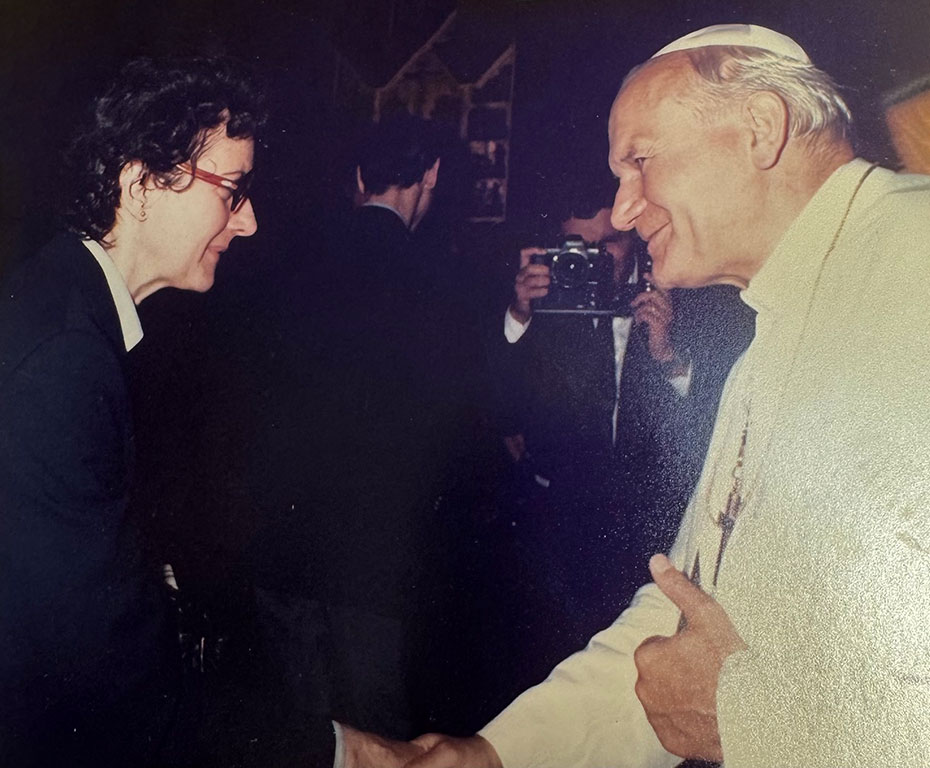

She joined Fordham in 1979 and taught courses in Israeli literature and film as part of Fordham’s Middle East Studies program. In 1992, she created the annual Nostra Aetate Dialogue series, which brought together Jewish and Christian scholars to address questions pertinent to Jewish-Catholic reconciliation. In 2002, she also helped found Fordham’s Jewish Texts Reading Group, which still meets today.

Hoffman was an accomplished painter. In 2015, she opened up about her creative process in a lecture at the Walsh Library. Last November, her art was displayed at Fordham’s Butler Gallery.

Hoffman was known at Fordham as a skilled instructor and generous mentor. Fordham professor of biology Jason Morris, Ph.D., said she taught him how to be a better teacher.

“I learned so much from teaching with Anne. She appreciated nuance: she had a deep mistrust of facile answers and sharply drawn lines,” he wrote in an email.

“Her integrity and her empathy (and despite what she said, her expertise) came across in everything she said and did.”

In 2003, she was honored with Fordham’s Outstanding Teaching in the Humanities Award, and in 2019, she was recognized for 40 years of service at Fordham. She retired in 2023 and was named professor emerita.

Nikolas Oktaba, a 2015 graduate, took a class with Hoffman, and like many students, he kept in touch with her after graduation. He called her a “fount of tranquil wisdom.”

“Not only did she put her students first, but she did so in a way that allowed them to see the perseverance, resilience, and strength that they already held within them,” he said.

At the time of her death, in addition to her painting, she was teaching writing skills at the Fortune Society, teaching Freud at the New York Psychoanalytic Institute, and conducting friendship-focused writing groups at the Asian University for Women (AUW) in Bangladesh via Zoom.

Leon Hoffman, M.D., Anne’s husband of 57 years, said that he would forever hold onto a memory of the two of them walking together when she was an undergraduate and he was attending medical school.

“We had one of those adolescent discussions of the time: would we marry someone who was not Jewish? I responded very quickly, ‘That is an academic discussion because I am going to marry you.’ She was shocked, but the rest is history,” he said.

“We were not tied at the hip, but we were tied with our brains and our love.”

In an interview last year, Hoffman recalled what her late father-in-law said when she received her first summer grant to travel to Israel to explore Agnon’s archive.

“He observed that it truly is the ‘goldeneh medineh’ (a Yiddish term referring to the U.S. as the golden land) when a Catholic university gives a Jewish girl money to go to Israel to work on Agnon,” she said.

“Even more than the material support, his remark captures something of the openness and generosity that have been my experience of this university, my academic home for over 40 years.”

Hoffman is survived by her husband, Leon Hoffman, M.D.; her children, Miriam Hoffman, M.D. (Steven Kleiner, M.D.) and Liora Hoffman, Ph.D. (Rob Yalen); her brother, David Golomb; her niece, Danielle Golomb, M.D.; her nephew, Jesse Golomb; and her grandchildren Shoshana, Elisheva, and Hillel Hoffman Kleiner and Greta and Max Yalen.

A memorial service open to the University community will be announced at a later date.

]]>An expert on Russia and the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, Rosenthal published numerous books and articles, including New Myth, New World: From Nietzsche to Stalinism (Penn State U. Press, 2002)—seen as an authoritative study of Nietzsche’s influence in Russia. Her work was cited repeatedly by scholars around the globe.

She joined the faculty of Fordham in 1970 and taught undergraduate and graduate students for 45 years. In 1990, she became the first woman promoted to full professor in the history department.

In 2010, at a ceremony where she was honored for 40 years of service at Fordham, Rosenthal was lauded for having “earned a place in the star-studded pantheon of European historians.”

Maryanne Kowaleski, Ph.D., the Joseph Fitzpatrick S.J. Distinguished Professor Emerita of History and Medieval Studies at Fordham, said that when she arrived on campus in 1982, Rosenthal was part of a faculty group called Women at Rose Hill that advocated for issues such as fair pay.

“It was a huge influence during my first years, not only because it allowed me to meet many of the other female faculty at the University but also because of the supportive community it provided at the time,” she said.

She also taught courses focused on Tsarist and 20th-century Russia, European intellectual history, and religion and revolution. Among students, Rosenthal was also known for her classes on the history of food, women in modern European history, and the occult. She was often sought after as an expert on the Soviet Union; she appeared on television a show on Ivan the Terrible for A&E’s Biography Series.

Rosenthal was born on March 24, 1938, in New York City and grew up, along with her brother Bernard, in the South Bronx. She earned a bachelor’s degree in history from City College of New York, a master’s degree in history from the University of Chicago, and in 1970, a Ph.D. in history from the University of California, Berkeley.

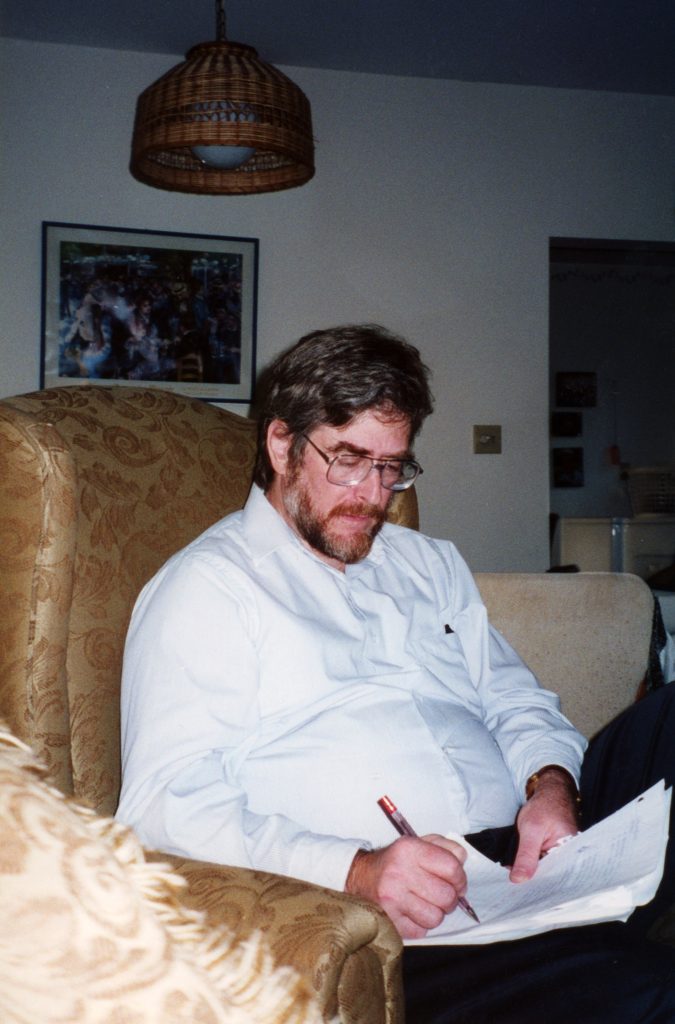

Her daughter Lara said some of her most vivid memories of her mother include her sitting in a black leather reclining chair with a book and a yellow notepad. When Lara was 8, her friends visited for a sleepover, and instead of playing games, she said, they tried to count how many books her mother had on the wall.

“In high school, sometimes I would leave one of my books from English class or a history class on the coffee table, and when I came home from school, she would have read the whole thing, cover to cover in one day,” she said.

“Her superhuman reading speed astounded and completely annoyed me, as I was just a mere mortal in my reading speed.”

Although Parkinson’s Disease took a toll on her mother, Lara said as her body got weaker, her spirit grew stronger, and they grew closer.

“Many years ago, Bernice said she wanted the words Eshet Chayil, which is Hebrew for ‘a woman of valor,’ on her headstone. At that time, I was annoyed at her and just said something along the lines of ‘Ok, fine,’” she said.

“These last few years, we were able to have some very honest and healing conversations that were not possible earlier in her life, and this meant the world to me. She has earned her Eshet Chayil and it will be on her headstone with my love and my blessing.”

Rosenthal is survived by her daughter and her brother Bernard. A funeral was held on June 9.

]]>“He was a great scientist and a remarkable thinker. He loved every aspect of chemistry,” said his colleague Shahrokh Saba, Ph.D., a current chemistry professor who taught with Clarke for more than four decades. “Even a week or so before he passed, he was asking me to do something related to chemistry for him.”

Clarke served as chair of the chemistry department for six years. His collective research in biochemistry and neurochemistry led to more than 100 published articles and book chapters. Some of his research led to the creation of drug treatments, including one that he personally benefited from when he had a case of shingles. At Fordham, he helped to establish the University’s nuclear magnetic resonance facility, where faculty and students study the molecular structure of substances, said Saba.

‘I Never Dreamed of the Possibility’

Clarke was born in Kingston, Jamaica, on March 20, 1930, to Izzet Dudley Clarke and Ivy Clarke, née Burrows. He was a “rising star,” said Peter, but it was difficult for him to pursue his passions at home.

In 2017, Clarke spoke to Fordham News about his educational journey.

“I was the eldest of four children and the first in my immediate family to attend high school. There was no university in Jamaica at that time, and my parents couldn’t afford to send me abroad for higher education,” he recalled.

Clarke’s adviser at St. George’s College, a Jesuit high school, reached out to Fordham for help.

The University’s president at the time, Robert Gannon, S.J., offered Clarke a scholarship. He earned his bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1950 and continued at the University as a chemistry department assistant. He went on to complete his master’s degree in 1951 and his Ph.D. in 1955 from Fordham.

“I never dreamed of the possibility of such accomplishments as I was growing up,” Clarke said.

‘A New Life’ as a Chemist and Bronxite

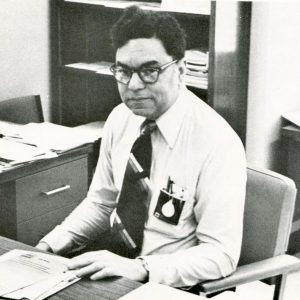

In 1962, he returned to Fordham as an associate professor of chemistry. He was promoted to full professor in 1970, later serving as department chair from 1978 to 1984.

“Don Clarke’s calm, kindly disposition provides an interesting contrast to his fierce love of learning and his intense dedication to his field of biochemistry,” reads his citation from Fordham’s 2022 Convocation, where he received a standing ovation for his longtime service.

Clarke was a fellow of the American Chemical Society, where he also served as chair and councilor of the New York section. Before joining Fordham’s faculty, he held research positions at the University of Toronto, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York Psychiatric Institute, and Columbia University, continuing his work with the Mount Sinai School of Medicine while working at Fordham.

“He was a stream of references, papers, educational techniques, lab procedures, and amazing insight into the fundamentals of academic chemistry,” said Frank Sena, Ph.D., an adjunct professor who first met Clarke when Clarke was a young faculty member and Sena was a chemistry doctoral student. “Very recently when this semester began, I wrote to him expressing how strange it was without him on Thursday afternoons. … [John Mulcahy Hall] will be emptier without him.”

Clarke retired from Fordham last year, concluding nearly 70 years at the University—as both a faculty member and a three-time Ram.

“The fact that he had gotten the president’s scholarship in 1948, there was always [this sense of]payback, I think, on some level,” said his son Peter, adding that Fordham became his father’s second home. “It was the thing that helped him leave Jamaica and start a new life. Fordham treated him well, so he treated Fordham well.”

For more than 50 years, Clarke lived in a Bronx house that was about a mile from the Rose Hill campus, said his son. He walked across Fordham Road to campus every day, carrying his briefcase, until it became difficult for him to walk. (Instead, he took the bus.)

In his spare time, Clarke was an avid puzzle solver who worked on The New York Times crossword puzzle every day, according to his family obituary. He inspired his great-grandchildren to play Sudoku.

Clarke is predeceased by his parents and his wife, Marie Clarke, née Burrowes; daughter Carol Halper; sons Stephen Clarke and Ian Clarke; and daughter-in-law Dawn. He is survived by his children Paula Clarke, David Clarke, Sylvia Clarke, and Peter Clarke; seven grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

A funeral Mass for Clarke was held at the Church of the Holy Spirit in Stamford, Connecticut, on Feb. 29, directly followed by his burial at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York. A Fordham memorial service will be held at the University Church on April 6 at 11 a.m., followed by a reception. Gifts in Clarke’s name may be made to Fordham University or the Exchange Club of Stamford.

“We pray hard for Luke’s family and friends who are grieving right now at this terrible tragedy,” wrote Tania Tetlow, president of Fordham, in a message to the University community. “We will forever hold Luke’s memory in our hearts.”

A Man for Others

Santos immersed himself in politics at a young age. He became involved in political campaigns when he was 14, working for well-known elected officials and campaign staff across Massachusetts and beyond. When he moved to New York City and became a Fordham student, he balanced his coursework with bolstering the New York City Council campaigns for Julie Won, Yusef Salaam, and Christopher Bae. Most recently, he served as a wealth management intern for The Taylor Group at Morgan Stanley.

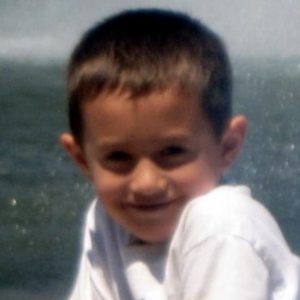

Santos was born on April 4, 2003, in Newton, Massachusetts. He graduated from Cambridge Rindge and Latin School, a public high school, where he was a member of the National Honor Society.

Santos became interested in politics after an 8th-grade field trip to the Massachusetts State House. He soon printed his own business cards, donned his suit and tie, and returned to the state house on his own to introduce himself to whomever he could, according to an obituary written by his family.

As a high school student, he provided support for several election campaigns, managing staff and budgets and canvassing local neighborhoods, according to his LinkedIn profile. At 15 years old, he even called into C-SPAN to share his thoughts on the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Later, he helped plan the 2018 Democratic State Convention in Massachusetts and the statewide coordinated campaign. He played a role in the campaigns of many candidates, including Joe Kennedy III’s run for U.S. Congress and Elizabeth Warren’s bids for U.S. Senate and president.

Santos was most passionate about affordable housing and social justice. When he was a junior in high school, he founded the Mask Up Project, a student group that distributed more than 800 homemade masks to those in need. Santos told his high school newspaper that he wanted to help “vulnerable communities such as our homeless population, who don’t have the luxury of socially distancing.”

‘Make Sure Every Single Voice Matters Just As Much As Mine’

Santos often shared his passion for politics on social media, including one post about the day he officially joined the Democratic Party.

“My grandpa grew up in public housing in New York, and my grandma was a school teacher who came from a family of immigrants and janitors. Today, their grandson (pre)registered as a Democrat. … I’m blown away that I actually have a chance for my voice to matter,” Santos posted on his Facebook profile in 2019. “And I’m gonna use this vote and fight like hell to make sure every single voice matters just as much as mine.”

Despite his own view on politics, he supported camaraderie among parties. In 2017, he posted a photo from a Youth Action March, noting “it was an inspiring moment when young Democrats and Republicans joined together to say we are the voice of America.”

In his spare time, Santos enjoyed traveling, skiing, fishing, and summering on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean with his family. He embraced his Filipino heritage through food, often introducing his friends to Filipino dishes in New York City and sharing his foodie adventures with his father.

“Luke brought joy to so many that were fortunate enough to have known him and will always be remembered for his independent spirit, love of nature, sharp analytical mind, boundless curiosity, and inspiring ambition,” Santos’s family wrote in his obituary.

Santos is survived by his mother, Allison Bailey; father, Albertino Santos; stepfather, Joseph Audette; siblings Grace Mary Audette and Samuel Lancaster Audette; grandparents Rita and Gary Bailey and Alicia Santos; and many other aunts, uncles, cousins, and friends.

A University memorial service will be held for Santos at the Rose Hill campus on Feb. 28 in Sacred Heart Chapel, Dealy Hall, at 12:45 p.m. His wake will be held on March 1 from 9:30 to 11 a.m. at Saint Cecilia Parish at 18 Belvidere Street, Boston, MA 02115. A funeral Mass will directly follow at the same location. Gifts in his name may be made to the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals-Angell Animal Medical Center.

]]>He was buried alongside his wife Susan Rogler, who died in 2011, and his mother, Carmen Canino, at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Tarrytown, New York.

Rogler, a native of Puerto Rico who moved to the United States when he was 11, joined the Fordham sociology department in 1974. He had just moved to the Bronx from Cleveland, where he was a professor at Case Western University. In 1977, he founded the Hispanic Research Center, which he directed until 1990.

Rogler’s area of expertise was in qualitative research on the social and mental health of families in Puerto Rico, the United States, and several Latin American countries.

He published extensively on the topic, from Migrant in the City: The Life of a Puerto Rican Action Group (Basic Books, 1972) to Barrio Professors: Tales of Naturalistic Research (Left Coast Press, 2008), which was his first work of fiction.

He was adept at securing grants for funding, such as “Help Patterns in Intergenerational Puerto Rican Families,” a three-year grant from the National Institute of Mental Health in 1976. He was sought after for his perspective; in 1985, for instance, he was appointed by New York City Mayor Ed Koch to the Mayor’s Commission on Hispanic Concerns.

Mary Powers, Ph.D., a professor emerita of sociology who was chair of the department when Rogler joined the faculty, said that Rogler was key to the department’s securing of the Schweitzer Chair, which was created in 1964 by the New York State Legislature to entice scholars to universities in the state.

“We were becoming a slightly more national university at the time, and he came as part of our interest in collaborating with Fordham and the University of Puerto Rico,” she said.

“He was delighted to come, and he worked hard at keeping the relationship between the two universities open.”

James R. Kelly, Ph.D., a professor emeritus of sociology who started two years before Rogler, fondly remembers playing squash with Rogler every week and beating him every time.

“Lloyd would always say, ‘Alright, Jim, you got me this time, but I’ll get you next time.’ He would never quit, and he just loved playing, and he never gave up on himself,” he said.

Kelly said that Rogler was a pioneer when it came to combining his own experience as an immigrant with his research.

Rogler’s son, Lloyd Rogler, said his father was driven in part by the fact that his grandfather was also a sociology professor. He was focused on the toll that immigration took on people’s psyches.

“He used to give grand rounds to psychiatrists about culturally sensitive therapy. For example, we might say, ‘Oh, I feel blue.’ But in Spanish, you don’t say, ‘Me siento azul.’ You have to have someone familiar with the culture of the person they are helping,” he said.

“My father was a scholar, an athlete, and intellectually curious about many things. I miss him every day.”

Rogler is survived by his daughter, Lynn Rogler Simonson; his son, Lloyd; stepsons Daniel Kim-Shapiro and David Shapiro-Ilan; grandsons Soleil, Mica, and Shai Kim-Shapiro, Teva Shapiro, and Amitai Ilan; great-granddaughter Chaya Mushka Shapiro; and his beloved caregiver Carmen Pilar Sierra.

]]>‘The Voice of Reason in an Often Unreasonable World’

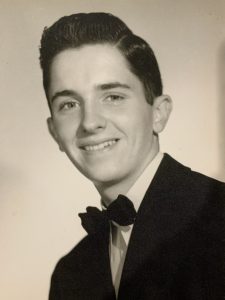

In a nearly five-decade career at CBS, the 1954 Fordham graduate was known for his distinctive voice and style, his intellect and sense of humor, and a warm, measured tone. He had a predilection for bow ties and a penchant for rhyme that earned him a reputation as CBS News’ “poet in residence.”

A master communicator, he was also a bestselling author of several books, a lyricist who scored an improbable hit in 1967, and a talented musician who played banjo with the Boston Pops and piano with the New York Pops. He could cover hard news “as straight as a string,” as he once put it, and deliver poignant human-interest stories with a wit and authenticity that endeared him to generations of listeners and viewers—both on Sunday Morning and on his syndicated radio show, The Osgood File.

“Charles Osgood has been a presence in all of our lives for decades,” said Tania Tetlow, president of Fordham. “His gentle and poetic delivery of the news, the wisdom of his observations—everything about him spoke of steadiness and integrity. He was the voice of reason in an often unreasonable world. We will all miss him terribly.”

‘The Theater of the Mind’

Born in the Bronx in 1933, Charles Osgood Wood III moved to Baltimore with his family in 1939 and grew up in the city’s Liberty Heights neighborhood, an experience he recalled in his 2004 memoir, Defending Baltimore Against Enemy Attack: A Boyhood Year During World War II. The year was 1942, and it was “the best of times and the worst of times,” he wrote, as he was surrounded by siblings, friends, and baseball—but against the backdrop of the Great Depression and World War II.

“Although memory has a built-in sugarcoater, and childhood is seen through the cotton candy of time, I have always been certain that there was a genuine sweetness to the days when I was nine years old and the country was united in winning the last good war, if there could have been such a thing,” he wrote.

It was also a time when he developed his love for radio, which he called the “Theater of the Mind” and “the greatest show on earth.”

An Education in the ‘Process of Orderly Thinking’

Osgood moved back north in 1946 to attend St. Cecilia High School in Englewood, New Jersey, before returning to the borough of his birth as a student at Fordham College at Rose Hill. He majored in economics—“not communication arts or journalism, as some might think,” he told Fordham Magazine in 1980.

“In those days at Fordham we also studied such arcane subjects as epistemology, cosmology, and ontology. It didn’t seem possible that I’d even make a living from them, but I swear I am! That’s because they developed in me the process of orderly thinking—the methodology of going from one step to another,” he said.

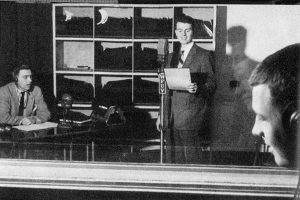

Osgood honed his broadcasting craft working at WFUV, Fordham’s public media station, during his years at Rose Hill. The station, founded in 1947, was just a few years old when he started. He eventually hosted his own show, No Soap Opera, and worked alongside other future luminaries including Alan Alda, FCRH ’56. “When I wasn’t on duty there I would just stay around because I enjoyed it so much,” he said.

After graduating in 1954 with that radio experience, Osgood was hired as an announcer by WGMS, a classical music station based in Washington, D.C. Soon after, though, he joined the military as an announcer for the United States Army Band, a role that he held until 1957. While serving near the Arlington National Cemetery, Osgood took on jobs at several Washington, D.C.-area radio stations under pseudonyms, and in the book Kilroy Was Here: The Best American Humor from World War II, he tells the story of being tasked with DJing a closed circuit radio broadcast for President Dwight D. Eisenhower while the commander in chief recovered from a heart attack in Colorado in 1955.

“I was put into a studio with a stack of records that had all been chosen as his favorites,” Osgood recalled. “And I spent most of the day playing records for Eisenhower.”

During his stint with the Army Band, he also “got to write some lyrics for the band and chorus,” he said in the 1980 Fordham story. “That’s when I really began versifying.”

From the Army, Osgood returned to WGMS until 1962, when he got his first job in television as the general manager of WHCT in Hartford, Connecticut. When the station ran into budget issues and Osgood was fired in 1963, he got his next break thanks in part to a fellow Fordham graduate, Frank Maguire, FCRH ’56, who was in charge of program development at ABC in New York at the time. Osgood joined ABC Radio as a writer and co-host of Flair Reports, which featured human interest stories.

“It had been years since he had seen me work, but he had enough faith to recommend me for the job,” Osgood said of Maguire. It was at ABC that he decided to change his professional name. “My own name was Charles Wood, but since there was another fellow in broadcasting [at ABC] named Charles Woods, I decided to use my middle name, Osgood.”

Beginning a Long Tenure at CBS

In 1967, he began working for CBS, where he would spend the rest of his career. Starting as a radio reporter for WCBS, he moved to the television news division in 1971, the same year he began hosting what would eventually become The Osgood File, short radio segments broadcast on stations across the country multiple times a day, four days a week.

On television, he started as a reporter and became an anchor of CBS Sunday Night News in 1981, followed by stints as a co-anchor of CBS Morning News, a news reader on CBS This Morning, and an anchor of CBS Afternoon News and CBS Evening News with Dan Rather.

It was his next role at CBS for which Osgood became best known: In 1994, he succeeded Charles Kuralt as host of Sunday Morning, where his trademark style as a calm, upbeat presence gave viewers a relaxing alternative to other Sunday morning programming.

“We accentuate the positive and don’t try to shock,” Osgood once told a reporter. ”I think there’s a growing appetite for that. We’re surrounded by shock.”

He hosted his last episode of the program on September 25, 2016, signing off with his signature “I’ll see you on the radio,” before thanking his viewers and the staff of the show. He continued to host episodes of The Osgood File until December 2017.

Osgood received numerous honors throughout his career. He was inducted into the National Association of Broadcasters Hall of Fame in 1990, earned a lifetime Emmy Award in 2018, and received many other accolades, including the Walter Cronkite Award for Excellence in Journalism, the Radio Television Digital News Association’s Paul White Award, four other Emmy Awards, and three Peabody Awards.

The Patron Saint of WFUV News

In 2008, WFUV honored Osgood alongside Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully, FCRH ’49, one of the first student voices on the station, with lifetime achievement awards in news and sports broadcasting, respectively. The awards, subsequently renamed in their honor, are presented annually to journalists who reflect Osgood’s and Scully’s standard of excellence.

“All of us at the station are saddened by Charles Osgood’s passing,” said Chuck Singleton, general manager of WFUV. “He was the patron saint of WFUV News, a mentor to our young journalists, and a distinguished link to the station’s founding generation of news professionals. Charles liked to say, ‘I went to the University of WFUV.’”

Osgood stayed extremely engaged with his alma mater and WFUV throughout his life. He was a Fordham trustee fellow and an emcee at numerous Fordham events, including the annual Fordham Founder’s Dinner, where he was among the honorees in 2005. Fordham also honored him in 2010, when he was inducted into the University’s Hall of Honor. He received an honorary degree from Fordham and delivered the commencement address to the Class of 1988, encouraging them to “stand for the values that shaped you here at Fordham.”

He occasionally returned to WFUV and was a frequent attendee of the station’s annual On the Record gala, at which other broadcasting legends—including Ted Koppel, a friend who started at ABC on the same day as Osgood in 1963, and Jane Pauley, who succeed him as host of Sunday Morning—received the Charles Osgood Lifetime Achievement Award.

“Everything I learned in my career, I learned at FUV,” Osgood said at the station’s 60th anniversary celebration in 2007. And while he thought the station’s new-at-the-time broadcast center on the lower level of Keating Hall was “better than CBS,” he reminded the audience that “it’s not equipment that teaches you. The most important equipment is not in a box, but what goes on in your own brain and your own heart.”

A Mentor to Fordham Students and Alumni

That lesson is one he conveyed to generations of Fordham graduates, including Emmy Award-winning producer Sara Kugel, FCRH ’11, who started working at Sunday Morning as a broadcast associate in 2012.

“I grew up watching Sunday Morning, and that was just a routine we had in our household. It was the only show my family really watched together,” she recalled, noting that she was “very much drawn” to Osgood’s warmth, gravitas, and intelligence.

“I wasn’t sure if I wanted to go into journalism then, but … once I started looking at Fordham, the fact that WFUV existed on campus, and that it had produced Charles Osgood? You can’t get it better. There’s nothing more inspiring than that.”

Over the years, the two bonded over their shared Fordham connection. Kugel recalls listening to a WFUV livestream of a Fordham football game with him one Saturday afternoon. “Of all the people I’ve met, I would say I found him to be very authentic,” she said. “Who he was on camera, really, it matched who he was in person.”

CBS New York’s Alice Gainer, FCRH ’04, echoed that sentiment. Following her Tuesday evening segment on Osgood’s life and legacy, the award-winning anchor and reporter shared some personal thoughts about Osgood with viewers, noting that in 2013, she “had the privilege of sitting on a journalism panel with him, since we’re both Fordham and WFUV alums.”

“What stood out to me was just how sharp he was—everything about him was so distinctive: his voice, his style. You know, you turn on the TV now, you see a lot of the same. He truly stood out. He leaves quite a legacy. And I have to point out, I’m sitting there thinking, ‘What am I doing on a panel with Charles Osgood?’ But he didn’t treat me that way. He treated me like a peer, and that meant so much. And he, you know, he’s still inspiring so many journalists to this day.”

A Fordham Family

The Fordham connection extended to his family. His wife, Jean Crofton, graduated from Fordham College at Lincoln Center in 2002, and two of their sons, Kenneth Winston Wood, FCLC ’98, and Jamie Wood, FCLC ’05, are Fordham alumni.

Fordham was “the first place where he was given a voice and the ability to tell stories on a platform when there were not as many platforms to be able to captivate an audience,” Jamie Wood said. “I think he always felt a great deal of gratitude and indebtedness to the Fordham community for creating the conditions that allowed that to happen.”

Wood added that his father’s disposition and personality on TV and radio reflected his personality at home.

“There was not really much of a performance element to it just because it’s just who he was,” he said. “He was the single most optimistic person that I’ve ever known. I think that he had an ability to see the inherent goodness of anyone and led with any storytelling or any interaction with that baseline assumption, that there’s fundamental good in every person that he is talking to, that he’s engaging in some way, and I think that that’s one of the things that made him beloved and endeared by so many.”

A Life Filled with Music and Community

While Osgood was known most widely for his talking and writing, many will also remember him as an enthusiastic singer, musician, and composer—who not only loved to perform for friends and family but who wrote the lyrics to two songs that achieved some level of wider success, “Gallant Men” and “Black is Beautiful.”

“I will always treasure being on set when Charlie would play the piano and sing,” Kugel said. “Witnessing Charles Osgood play ‘I’ll be Home for Christmas’ on the Sunday Morning set was pure magic. Only a few people would be in the studio during those tapings, but it seemed there wasn’t a dry eye in the room. We all knew we had witnessed something very special. It felt like heaven.”

In his final radio segment, broadcast on December 29, 2017, Osgood gave a brief history of Robert Burns’ familiar poem “Auld Lang Syne” and recited a version of his own, over the sound of pensive bagpipes, as a farewell to his listeners:

“The memories of days gone by—old times, old friends, and all—

faces, voices of the past our minds can still recall.

They live still in your memory, as they still live in mine,

as we lift a cup this Sunday eve for Auld Lang Syne.”

Osgood is survived by his wife, Jean Crofton; their five children, Kathleen Wood Griffis, Kenneth Winston Wood, Anne-E. Wood, Emily J. Wood, and Jamie Wood; two siblings; and six grandchildren.

“My dad above all loved other people’s company,” Jamie Wood said. “It wasn’t being a public figure, it wasn’t being a journalist. He just loved being around community, and so thank you for welcoming him into your homes and into your radios to be able to … share stories, to share the better parts of humanity. And he will see you on the radio.”

—Ryan Stellabotte contributed to this story.

]]>“Orlando was a quiet, thoughtful leader who was committed to the idea that we can keep each other safe and hold one another accountable without resorting to punishment,” said Professor of Sociology Jeanne Flavin, Ph.D. “He was someone who supported all students and his junior colleagues.”

A Symbolic Cup of Coffee

In 1987, Rodriguez joined Fordham as senior research associate at the University’s former Hispanic Research Center, where he studied mental health in Latinx communities. From 1990 to 1997, he served as the center’s director. Rodriguez also taught in the Sociology and Anthropology Department at Rose Hill, serving in several positions, including department chair, until his retirement in 2020.

He and his wife experienced a devastating loss during the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York City: the death of their son, Gregory, who worked on the 103rd floor of the World Trade Center. Four days later, they penned an open letter, “Not In Our Son’s Name,” asking the U.S. government to resist calls for military retaliation. Their letter was included in the book Voices of a People’s History of the United States (Seven Stories Press, 2004), inspiring a series of public readings on stages nationwide, as well as the 2009 film “The People Speak.” The story of their response to their son’s death was also spotlighted in the 2015 documentary “In Our Son’s Name,” aired on PBS.

Despite his pain, Rodriguez was resilient. “He would bring me a little cup of espresso in bed every morning before I got up,” said his wife, Phyllis Schafer Rodriguez, his partner of nearly six decades. “We both felt hopeless and devastated after Greg was killed. The next morning, after hardly sleeping … he walked in with two cups of espresso [for us]. That’s emblematic, in a quiet way, of who he was.”

At Fordham, Rodriguez turned his grief into action. With adjunct professor Kerry Sweet, he created and co-taught the course Terrorism and Society, profiled by The New York Times, which aimed to help students better understand terrorism. He was also instrumental in creating the Peace and Justice Studies minor program and the criminology course Harm and Justice, Crime and Punishment.

‘I Credit Him with the Person I Am Today’

Among his mentees was Tia Noelle Pratt, GSAS ’01, ’10, who said Rodriguez saved her career. He helped her to navigate a complex administrative issue, allowing her to finish her dissertation. And when she became temporarily homeless due to a fire, Rodriguez and his wife gave her a place to stay—their home.

“He taught me to keep going, even when it looks like you won’t get there,” said Pratt, who earned her master’s and doctorate degrees in sociology.

He championed scores of other students, including Stacy Torres, Ph.D., FCLC ’02, connecting her with life-changing opportunities, counseling her through personal issues, and helping her family deal with their post-9/11 grief, all while tending to his own.

“I credit him with the person I am today, and for helping me to reach my current position as a sociology professor myself,” said Torres, who now teaches at University of California, San Francisco.

Rodriguez was born in Havana, Cuba, on Feb. 22, 1942, to Marta Iglesias, a seamstress, and Jesus Rodriguez, a cracker salesman. When he was 13 years old, the family of three moved to New York City. Rodriguez graduated from Samuel J. Tilden High School in Brooklyn. He went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in sociology from City College of New York and a Ph.D. in sociology from Columbia University. Besides working at Fordham, where he spent most of his academic career, he taught at Brooklyn College and conducted research at the Vera Institute of Justice. He also taught sociology of religion at the Green Haven and Sing Sing correctional facilities in New York state as a volunteer at Rising Hope, a college-level certificate program.

In his day-to-day life, Rodriguez was a quiet man who spoke judiciously, while entertaining people with his dry sense of humor and witty one-liners, said those who knew him. He was also an avid reader of fiction, nonfiction, science fiction, and detective novels. He attended the Memorial United Methodist Church in White Plains, New York, and participated in Braver Angels, an organization that promotes civil conversations across political differences.

Rodriguez is survived by his wife; daughter, Julia E. Rodriguez and her husband, Charles B. Forcey; daughter-in-law, Elizabeth Soudant; and three grandchildren. He is predeceased by his son.

A private burial was held on Jan. 13 at White Plains Rural Cemetery. A public memorial service will be held this spring. Donations in his memory may be made to Rising Hope or Peaceful Tomorrows.

Watch the documentary trailer for “In Our Son’s Name” below.

]]>

“He was like another dad to me. He befriended, loved, kept up with, and supported me,” said Catherine McGovern, FCRH ’81, echoing the sentiments of alumni of many generations.

Father Daly served as director of Campus Ministry at Fordham from 1980 to 1987. Later, he became assistant alumni chaplain, providing pastoral support to Fordham’s global community of more than 200,000 alumni from 2015 to 2019. This included attending alumni receptions and retreats, as well as writing seasonal prayers to alumni, often with a personal and poignant touch. He also served as chaplain to the women’s basketball team from 2017 to 2019, earning recognition from Fordham Athletics for his work. (Fun fact: His old Campus Ministry office served as the office of the fictional Father Damien Karras in the movie The Exorcist, said Beth Tarpey Evans, FCRH ’84, who once worked in Father Daly’s office. “He was so proud of that! He left that nameplate on the door,” Evans said.)

A Second Father

What alumni remember most about Father Daly is the way he cared for them in the same spirit as a father, comforting them during difficult times and rejoicing with them during the most important moments of their lives, said those who knew him. He was a gregarious, fun, witty, and kind priest who took great pride in their accomplishments, said McGovern, who is part of a circle of women that fondly refer to themselves as “Leo’s Ladies.”

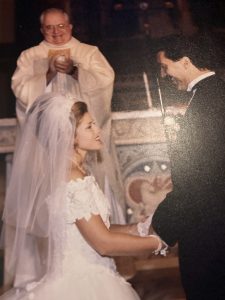

He traveled across the country, marrying, baptizing, and blessing thousands of people—sometimes multiple generations in a single family, said his niece, Elizabeth Shortal Aptilon, FCLC ’85, GABELLI ’90.

“You don’t meet that many people who are genuinely good people. There aren’t that many people that stay in touch with you for decades. But my uncle was someone who really maintained lifelong friends,” said Aptilon.

An Advocate at Home and Abroad

Father Daly was born on July 29, 1930, in Brooklyn, New York, to Joseph Daly, a salesman, and Margaret McGowan Daly, a homemaker, both of whom had Irish heritage. He graduated from Brooklyn Preparatory High School, a Jesuit school in his home borough. He went on to earn a Master of Arts degree from Fordham’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and a degree in counseling psychology from Columbia University.

Father Daly entered the Society of Jesus in 1948 and was ordained a priest at the Fordham University Church in 1961. He served his fellow New Yorkers in many roles, including assistant principal at St. Peter’s Prep in Jersey City; administrator at Loyola Seminary in Shrub Oak, New York; high school counselor at Regis High School and Xavier High School in Manhattan; community superior at Xavier High School; and assistant to the rector of the Jesuit community at St. Peter’s College in Jersey City. He conducted retreat work as a staff member and director at St. Ignatius Retreat House on Long Island before it closed in 2012. Father Daly also served communities abroad, as campus minister at the University of Guam and as a chaplain at a U.S. Army missile range in the Marshall Islands.

Father Daly was a great storyteller who treasured time with family and friends, said his niece. In his spare time, he loved listening to jazz music and playing golf, she said.

His friend and former colleague Daniel J. Gatti, S.J, who used to serve as Fordham’s alumni chaplain, recalled the time Father Daly nearly made a 165-yard hole in a single shot—and almost won a free car in the process.

“Leo was about eight inches [away],” said Father Gatti, who had attended a Fordham Gridiron Golf Outing with Father Daly and two other Jesuits. “The whole day, no one won the car. … But Leo, I think, was the closest,” he said, chuckling.

‘He Served God’s People Well’

Four years ago, he was diagnosed with a parotid gland tumor, said McGovern, an OB-GYN whom Father Daly jokingly called his “personal obstetrician.” Despite dealing with serious illness during his final years—surgeries, radiation, immunotherapy, and partial loss of vision and hearing—Father Daly remained cheerful and involved with his Jesuit community and those he loved, said those who knew him.

“Throughout his long life, he served God’s people well,” Father Gatti said.

Father Daly is survived by his niece; grandnephew Brandon Craig Aptilon, GABELLI ’22; grandnephew Bradley Edward Aptilon; and nephew, James P. Shortal, his wife, Denise, and their daughter, Kristin. He is predeceased by his sister, Helen Shortal, née Daly, GSE ’49. His wake will be held at Murray-Weigel Hall on Jan. 19 from 3 to 8 p.m. The funeral Mass will be held the next day at the University Church at 11 a.m. and livestreamed on Campus Ministry’s website. Father Daly will be buried at the Jesuit Cemetery in Auriesville, New York. Gifts in his name may be made to the Leo Daly, S.J., Scholarship Fund.

“[Ross’s] devil-may-care demeanor, hip Williamsburg filmmaker act could seem like armor. Underneath … was this mushy, soft sweetheart,” said Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock, head of Fordham’s visual arts program at the Lincoln Center campus. “He is the last person who would want to be put on a pedestal. But these characters who come into your life … they become your family, and it’s quite impossible to imagine a world where he’s not padding around [Fordham] in his Chuck Taylors.”

‘The Muse Was Life; the Medium Was Film’

McLaren taught film and media production to Fordham students as an artist in residence. His work, which has been described as “abstract,” “playful,” and “ironic,” has been featured in Fordham’s annual faculty show at the Ildiko Butler Gallery. McLaren often left interpretation of his art up to his viewers. “The kind of artwork I like [is]not nailed down by the artist’s definition,” he once said.

The art that he truly loved, said his colleague Joe Lawton, was experimental non-narrative independent cinematic film.

“He had great knowledge of Walt Disney cartoons, Hollywood films, et cetera, but his real passion was the descriptive and inherent equalities in the idea of film itself,” said Lawton, associate clinical professor of photography. “He was also curious about … life itself. The muse was life; the medium was film.”

Unconventionally Living Cura Personalis

As a faculty member, McLaren wasn’t keen on volunteering for administrative tasks, said Apicella-Hitchcock, but he never hesitated to help out his students.

“I would find him assisting a student one-on-one on how to load Super 8 film into a projector, way beyond his afternoon class. In an odd, quirky way, in his anti-establishment personality way, he embodied cura personalis,” Apicella-Hitchcock said.

McLaren was an “unconventional” professor who encouraged his students to challenge existing norms and think outside the box, said former student Luke Momo, FCLC ’19. He also helped his students improve their craft by pinpointing the deeper meaning behind their self-produced films, said Momo, who noted that’s just what McLaren did when he attended the premiere of Momo’s first feature film, Capsules, at a Manhattan film festival last year.

McLaren gave his students gifts beyond filmmaking, too. “When I was in undergrad, I wasn’t [able to laugh at myself]. I had a lot of pride,” Momo said. “Being more honest and vulnerable…some of those emotions are things that Professor Ross gave me.”

Other former students said McLaren’s vision of the world made them think.

“Ross said once, ‘How strange it is that we sit in dark rooms and watch shadows on the wall to find meaning within ourselves,’” a former student commented on a tribute post. “That always stuck with me.”

A ‘Goofy’ Friend with a Parrot and Two Turtles

McLaren was born on December 4, 1953, in Ontario, Canada. He earned his M.F.A. from Ontario College of Art and taught at many institutions, including Cooper Union and Pratt Institute. His work has been screened at institutions worldwide, including MoMA in New York City and the British Film Institute Southbank in London, and found a permanent home in many art institutions. He received multiple honors, including the Millennium Achievement Award for his contributions to the arts and education. In addition, he founded Funnel Film Theatre in Toronto, an underground film collective active in the 70s and 80s that one writer recently described as “the most important locale for experimental film in Canada.”

He lived in his loft apartment in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where he enjoyed growing plants on the rooftop; spending time with his beloved parrot, Fwankie; and sunbathing with his two turtles, Flotsam and Jetsam, who had the privilege of their own kiddie pool, said Apicella-Hitchcock. He was also a big hockey fan.

From a distance, you might have assumed he was a “goofy wisecracker, a little cynical and sarcastic,” said Apicella-Hitchcock, but at his core, McLaren was a “thoughtful, warm, and loyal friend.”

McLaren is survived by his brother, Gary McLaren, and his sister, Catherine McLaren. A memorial in McLaren’s honor will be held on Feb. 16, 2024, at 6 p.m. at the Lincoln Center campus’s Lipani Gallery, where several of his films will be screened. Contact [email protected] for more information.