“He was a great scientist and a remarkable thinker. He loved every aspect of chemistry,” said his colleague Shahrokh Saba, Ph.D., a current chemistry professor who taught with Clarke for more than four decades. “Even a week or so before he passed, he was asking me to do something related to chemistry for him.”

Clarke served as chair of the chemistry department for six years. His collective research in biochemistry and neurochemistry led to more than 100 published articles and book chapters. Some of his research led to the creation of drug treatments, including one that he personally benefited from when he had a case of shingles. At Fordham, he helped to establish the University’s nuclear magnetic resonance facility, where faculty and students study the molecular structure of substances, said Saba.

‘I Never Dreamed of the Possibility’

Clarke was born in Kingston, Jamaica, on March 20, 1930, to Izzet Dudley Clarke and Ivy Clarke, née Burrows. He was a “rising star,” said Peter, but it was difficult for him to pursue his passions at home.

In 2017, Clarke spoke to Fordham News about his educational journey.

“I was the eldest of four children and the first in my immediate family to attend high school. There was no university in Jamaica at that time, and my parents couldn’t afford to send me abroad for higher education,” he recalled.

Clarke’s adviser at St. George’s College, a Jesuit high school, reached out to Fordham for help.

The University’s president at the time, Robert Gannon, S.J., offered Clarke a scholarship. He earned his bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1950 and continued at the University as a chemistry department assistant. He went on to complete his master’s degree in 1951 and his Ph.D. in 1955 from Fordham.

“I never dreamed of the possibility of such accomplishments as I was growing up,” Clarke said.

‘A New Life’ as a Chemist and Bronxite

In 1962, he returned to Fordham as an associate professor of chemistry. He was promoted to full professor in 1970, later serving as department chair from 1978 to 1984.

“Don Clarke’s calm, kindly disposition provides an interesting contrast to his fierce love of learning and his intense dedication to his field of biochemistry,” reads his citation from Fordham’s 2022 Convocation, where he received a standing ovation for his longtime service.

Clarke was a fellow of the American Chemical Society, where he also served as chair and councilor of the New York section. Before joining Fordham’s faculty, he held research positions at the University of Toronto, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York Psychiatric Institute, and Columbia University, continuing his work with the Mount Sinai School of Medicine while working at Fordham.

“He was a stream of references, papers, educational techniques, lab procedures, and amazing insight into the fundamentals of academic chemistry,” said Frank Sena, Ph.D., an adjunct professor who first met Clarke when Clarke was a young faculty member and Sena was a chemistry doctoral student. “Very recently when this semester began, I wrote to him expressing how strange it was without him on Thursday afternoons. … [John Mulcahy Hall] will be emptier without him.”

Clarke retired from Fordham last year, concluding nearly 70 years at the University—as both a faculty member and a three-time Ram.

“The fact that he had gotten the president’s scholarship in 1948, there was always [this sense of]payback, I think, on some level,” said his son Peter, adding that Fordham became his father’s second home. “It was the thing that helped him leave Jamaica and start a new life. Fordham treated him well, so he treated Fordham well.”

For more than 50 years, Clarke lived in a Bronx house that was about a mile from the Rose Hill campus, said his son. He walked across Fordham Road to campus every day, carrying his briefcase, until it became difficult for him to walk. (Instead, he took the bus.)

In his spare time, Clarke was an avid puzzle solver who worked on The New York Times crossword puzzle every day, according to his family obituary. He inspired his great-grandchildren to play Sudoku.

Clarke is predeceased by his parents and his wife, Marie Clarke, née Burrowes; daughter Carol Halper; sons Stephen Clarke and Ian Clarke; and daughter-in-law Dawn. He is survived by his children Paula Clarke, David Clarke, Sylvia Clarke, and Peter Clarke; seven grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

A funeral Mass for Clarke was held at the Church of the Holy Spirit in Stamford, Connecticut, on Feb. 29, directly followed by his burial at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York. A Fordham memorial service will be held at the University Church on April 6 at 11 a.m., followed by a reception. Gifts in Clarke’s name may be made to Fordham University or the Exchange Club of Stamford.

“We pray hard for Luke’s family and friends who are grieving right now at this terrible tragedy,” wrote Tania Tetlow, president of Fordham, in a message to the University community. “We will forever hold Luke’s memory in our hearts.”

A Man for Others

Santos immersed himself in politics at a young age. He became involved in political campaigns when he was 14, working for well-known elected officials and campaign staff across Massachusetts and beyond. When he moved to New York City and became a Fordham student, he balanced his coursework with bolstering the New York City Council campaigns for Julie Won, Yusef Salaam, and Christopher Bae. Most recently, he served as a wealth management intern for The Taylor Group at Morgan Stanley.

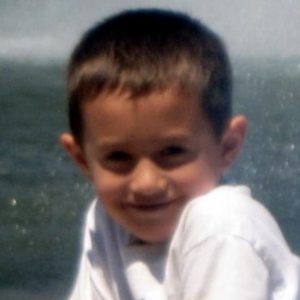

Santos was born on April 4, 2003, in Newton, Massachusetts. He graduated from Cambridge Rindge and Latin School, a public high school, where he was a member of the National Honor Society.

Santos became interested in politics after an 8th-grade field trip to the Massachusetts State House. He soon printed his own business cards, donned his suit and tie, and returned to the state house on his own to introduce himself to whomever he could, according to an obituary written by his family.

As a high school student, he provided support for several election campaigns, managing staff and budgets and canvassing local neighborhoods, according to his LinkedIn profile. At 15 years old, he even called into C-SPAN to share his thoughts on the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Later, he helped plan the 2018 Democratic State Convention in Massachusetts and the statewide coordinated campaign. He played a role in the campaigns of many candidates, including Joe Kennedy III’s run for U.S. Congress and Elizabeth Warren’s bids for U.S. Senate and president.

Santos was most passionate about affordable housing and social justice. When he was a junior in high school, he founded the Mask Up Project, a student group that distributed more than 800 homemade masks to those in need. Santos told his high school newspaper that he wanted to help “vulnerable communities such as our homeless population, who don’t have the luxury of socially distancing.”

‘Make Sure Every Single Voice Matters Just As Much As Mine’

Santos often shared his passion for politics on social media, including one post about the day he officially joined the Democratic Party.

“My grandpa grew up in public housing in New York, and my grandma was a school teacher who came from a family of immigrants and janitors. Today, their grandson (pre)registered as a Democrat. … I’m blown away that I actually have a chance for my voice to matter,” Santos posted on his Facebook profile in 2019. “And I’m gonna use this vote and fight like hell to make sure every single voice matters just as much as mine.”

Despite his own view on politics, he supported camaraderie among parties. In 2017, he posted a photo from a Youth Action March, noting “it was an inspiring moment when young Democrats and Republicans joined together to say we are the voice of America.”

In his spare time, Santos enjoyed traveling, skiing, fishing, and summering on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean with his family. He embraced his Filipino heritage through food, often introducing his friends to Filipino dishes in New York City and sharing his foodie adventures with his father.

“Luke brought joy to so many that were fortunate enough to have known him and will always be remembered for his independent spirit, love of nature, sharp analytical mind, boundless curiosity, and inspiring ambition,” Santos’s family wrote in his obituary.

Santos is survived by his mother, Allison Bailey; father, Albertino Santos; stepfather, Joseph Audette; siblings Grace Mary Audette and Samuel Lancaster Audette; grandparents Rita and Gary Bailey and Alicia Santos; and many other aunts, uncles, cousins, and friends.

A University memorial service will be held for Santos at the Rose Hill campus on Feb. 28 in Sacred Heart Chapel, Dealy Hall, at 12:45 p.m. His wake will be held on March 1 from 9:30 to 11 a.m. at Saint Cecilia Parish at 18 Belvidere Street, Boston, MA 02115. A funeral Mass will directly follow at the same location. Gifts in his name may be made to the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals-Angell Animal Medical Center.

“Orlando was a quiet, thoughtful leader who was committed to the idea that we can keep each other safe and hold one another accountable without resorting to punishment,” said Professor of Sociology Jeanne Flavin, Ph.D. “He was someone who supported all students and his junior colleagues.”

A Symbolic Cup of Coffee

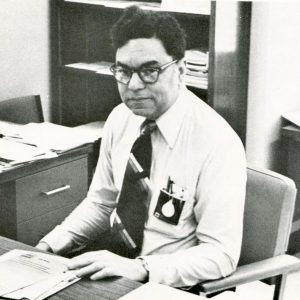

In 1987, Rodriguez joined Fordham as senior research associate at the University’s former Hispanic Research Center, where he studied mental health in Latinx communities. From 1990 to 1997, he served as the center’s director. Rodriguez also taught in the Sociology and Anthropology Department at Rose Hill, serving in several positions, including department chair, until his retirement in 2020.

He and his wife experienced a devastating loss during the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York City: the death of their son, Gregory, who worked on the 103rd floor of the World Trade Center. Four days later, they penned an open letter, “Not In Our Son’s Name,” asking the U.S. government to resist calls for military retaliation. Their letter was included in the book Voices of a People’s History of the United States (Seven Stories Press, 2004), inspiring a series of public readings on stages nationwide, as well as the 2009 film “The People Speak.” The story of their response to their son’s death was also spotlighted in the 2015 documentary “In Our Son’s Name,” aired on PBS.

Despite his pain, Rodriguez was resilient. “He would bring me a little cup of espresso in bed every morning before I got up,” said his wife, Phyllis Schafer Rodriguez, his partner of nearly six decades. “We both felt hopeless and devastated after Greg was killed. The next morning, after hardly sleeping … he walked in with two cups of espresso [for us]. That’s emblematic, in a quiet way, of who he was.”

At Fordham, Rodriguez turned his grief into action. With adjunct professor Kerry Sweet, he created and co-taught the course Terrorism and Society, profiled by The New York Times, which aimed to help students better understand terrorism. He was also instrumental in creating the Peace and Justice Studies minor program and the criminology course Harm and Justice, Crime and Punishment.

‘I Credit Him with the Person I Am Today’

Among his mentees was Tia Noelle Pratt, GSAS ’01, ’10, who said Rodriguez saved her career. He helped her to navigate a complex administrative issue, allowing her to finish her dissertation. And when she became temporarily homeless due to a fire, Rodriguez and his wife gave her a place to stay—their home.

“He taught me to keep going, even when it looks like you won’t get there,” said Pratt, who earned her master’s and doctorate degrees in sociology.

He championed scores of other students, including Stacy Torres, Ph.D., FCLC ’02, connecting her with life-changing opportunities, counseling her through personal issues, and helping her family deal with their post-9/11 grief, all while tending to his own.

“I credit him with the person I am today, and for helping me to reach my current position as a sociology professor myself,” said Torres, who now teaches at University of California, San Francisco.

Rodriguez was born in Havana, Cuba, on Feb. 22, 1942, to Marta Iglesias, a seamstress, and Jesus Rodriguez, a cracker salesman. When he was 13 years old, the family of three moved to New York City. Rodriguez graduated from Samuel J. Tilden High School in Brooklyn. He went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in sociology from City College of New York and a Ph.D. in sociology from Columbia University. Besides working at Fordham, where he spent most of his academic career, he taught at Brooklyn College and conducted research at the Vera Institute of Justice. He also taught sociology of religion at the Green Haven and Sing Sing correctional facilities in New York state as a volunteer at Rising Hope, a college-level certificate program.

In his day-to-day life, Rodriguez was a quiet man who spoke judiciously, while entertaining people with his dry sense of humor and witty one-liners, said those who knew him. He was also an avid reader of fiction, nonfiction, science fiction, and detective novels. He attended the Memorial United Methodist Church in White Plains, New York, and participated in Braver Angels, an organization that promotes civil conversations across political differences.

Rodriguez is survived by his wife; daughter, Julia E. Rodriguez and her husband, Charles B. Forcey; daughter-in-law, Elizabeth Soudant; and three grandchildren. He is predeceased by his son.

A private burial was held on Jan. 13 at White Plains Rural Cemetery. A public memorial service will be held this spring. Donations in his memory may be made to Rising Hope or Peaceful Tomorrows.

Watch the documentary trailer for “In Our Son’s Name” below.

]]>

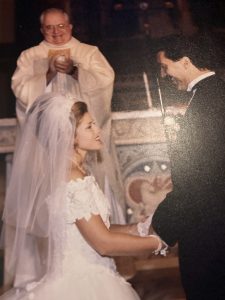

“He was like another dad to me. He befriended, loved, kept up with, and supported me,” said Catherine McGovern, FCRH ’81, echoing the sentiments of alumni of many generations.

Father Daly served as director of Campus Ministry at Fordham from 1980 to 1987. Later, he became assistant alumni chaplain, providing pastoral support to Fordham’s global community of more than 200,000 alumni from 2015 to 2019. This included attending alumni receptions and retreats, as well as writing seasonal prayers to alumni, often with a personal and poignant touch. He also served as chaplain to the women’s basketball team from 2017 to 2019, earning recognition from Fordham Athletics for his work. (Fun fact: His old Campus Ministry office served as the office of the fictional Father Damien Karras in the movie The Exorcist, said Beth Tarpey Evans, FCRH ’84, who once worked in Father Daly’s office. “He was so proud of that! He left that nameplate on the door,” Evans said.)

A Second Father

What alumni remember most about Father Daly is the way he cared for them in the same spirit as a father, comforting them during difficult times and rejoicing with them during the most important moments of their lives, said those who knew him. He was a gregarious, fun, witty, and kind priest who took great pride in their accomplishments, said McGovern, who is part of a circle of women that fondly refer to themselves as “Leo’s Ladies.”

He traveled across the country, marrying, baptizing, and blessing thousands of people—sometimes multiple generations in a single family, said his niece, Elizabeth Shortal Aptilon, FCLC ’85, GABELLI ’90.

“You don’t meet that many people who are genuinely good people. There aren’t that many people that stay in touch with you for decades. But my uncle was someone who really maintained lifelong friends,” said Aptilon.

An Advocate at Home and Abroad

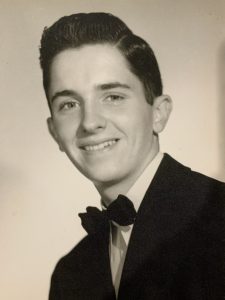

Father Daly was born on July 29, 1930, in Brooklyn, New York, to Joseph Daly, a salesman, and Margaret McGowan Daly, a homemaker, both of whom had Irish heritage. He graduated from Brooklyn Preparatory High School, a Jesuit school in his home borough. He went on to earn a Master of Arts degree from Fordham’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and a degree in counseling psychology from Columbia University.

Father Daly entered the Society of Jesus in 1948 and was ordained a priest at the Fordham University Church in 1961. He served his fellow New Yorkers in many roles, including assistant principal at St. Peter’s Prep in Jersey City; administrator at Loyola Seminary in Shrub Oak, New York; high school counselor at Regis High School and Xavier High School in Manhattan; community superior at Xavier High School; and assistant to the rector of the Jesuit community at St. Peter’s College in Jersey City. He conducted retreat work as a staff member and director at St. Ignatius Retreat House on Long Island before it closed in 2012. Father Daly also served communities abroad, as campus minister at the University of Guam and as a chaplain at a U.S. Army missile range in the Marshall Islands.

Father Daly was a great storyteller who treasured time with family and friends, said his niece. In his spare time, he loved listening to jazz music and playing golf, she said.

His friend and former colleague Daniel J. Gatti, S.J, who used to serve as Fordham’s alumni chaplain, recalled the time Father Daly nearly made a 165-yard hole in a single shot—and almost won a free car in the process.

“Leo was about eight inches [away],” said Father Gatti, who had attended a Fordham Gridiron Golf Outing with Father Daly and two other Jesuits. “The whole day, no one won the car. … But Leo, I think, was the closest,” he said, chuckling.

‘He Served God’s People Well’

Four years ago, he was diagnosed with a parotid gland tumor, said McGovern, an OB-GYN whom Father Daly jokingly called his “personal obstetrician.” Despite dealing with serious illness during his final years—surgeries, radiation, immunotherapy, and partial loss of vision and hearing—Father Daly remained cheerful and involved with his Jesuit community and those he loved, said those who knew him.

“Throughout his long life, he served God’s people well,” Father Gatti said.

Father Daly is survived by his niece; grandnephew Brandon Craig Aptilon, GABELLI ’22; grandnephew Bradley Edward Aptilon; and nephew, James P. Shortal, his wife, Denise, and their daughter, Kristin. He is predeceased by his sister, Helen Shortal, née Daly, GSE ’49. His wake will be held at Murray-Weigel Hall on Jan. 19 from 3 to 8 p.m. The funeral Mass will be held the next day at the University Church at 11 a.m. and livestreamed on Campus Ministry’s website. Father Daly will be buried at the Jesuit Cemetery in Auriesville, New York. Gifts in his name may be made to the Leo Daly, S.J., Scholarship Fund.

“[Ross’s] devil-may-care demeanor, hip Williamsburg filmmaker act could seem like armor. Underneath … was this mushy, soft sweetheart,” said Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock, head of Fordham’s visual arts program at the Lincoln Center campus. “He is the last person who would want to be put on a pedestal. But these characters who come into your life … they become your family, and it’s quite impossible to imagine a world where he’s not padding around [Fordham] in his Chuck Taylors.”

‘The Muse Was Life; the Medium Was Film’

McLaren taught film and media production to Fordham students as an artist in residence. His work, which has been described as “abstract,” “playful,” and “ironic,” has been featured in Fordham’s annual faculty show at the Ildiko Butler Gallery. McLaren often left interpretation of his art up to his viewers. “The kind of artwork I like [is]not nailed down by the artist’s definition,” he once said.

The art that he truly loved, said his colleague Joe Lawton, was experimental non-narrative independent cinematic film.

“He had great knowledge of Walt Disney cartoons, Hollywood films, et cetera, but his real passion was the descriptive and inherent equalities in the idea of film itself,” said Lawton, associate clinical professor of photography. “He was also curious about … life itself. The muse was life; the medium was film.”

Unconventionally Living Cura Personalis

As a faculty member, McLaren wasn’t keen on volunteering for administrative tasks, said Apicella-Hitchcock, but he never hesitated to help out his students.

“I would find him assisting a student one-on-one on how to load Super 8 film into a projector, way beyond his afternoon class. In an odd, quirky way, in his anti-establishment personality way, he embodied cura personalis,” Apicella-Hitchcock said.

McLaren was an “unconventional” professor who encouraged his students to challenge existing norms and think outside the box, said former student Luke Momo, FCLC ’19. He also helped his students improve their craft by pinpointing the deeper meaning behind their self-produced films, said Momo, who noted that’s just what McLaren did when he attended the premiere of Momo’s first feature film, Capsules, at a Manhattan film festival last year.

McLaren gave his students gifts beyond filmmaking, too. “When I was in undergrad, I wasn’t [able to laugh at myself]. I had a lot of pride,” Momo said. “Being more honest and vulnerable…some of those emotions are things that Professor Ross gave me.”

Other former students said McLaren’s vision of the world made them think.

“Ross said once, ‘How strange it is that we sit in dark rooms and watch shadows on the wall to find meaning within ourselves,’” a former student commented on a tribute post. “That always stuck with me.”

A ‘Goofy’ Friend with a Parrot and Two Turtles

McLaren was born on December 4, 1953, in Ontario, Canada. He earned his M.F.A. from Ontario College of Art and taught at many institutions, including Cooper Union and Pratt Institute. His work has been screened at institutions worldwide, including MoMA in New York City and the British Film Institute Southbank in London, and found a permanent home in many art institutions. He received multiple honors, including the Millennium Achievement Award for his contributions to the arts and education. In addition, he founded Funnel Film Theatre in Toronto, an underground film collective active in the 70s and 80s that one writer recently described as “the most important locale for experimental film in Canada.”

He lived in his loft apartment in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where he enjoyed growing plants on the rooftop; spending time with his beloved parrot, Fwankie; and sunbathing with his two turtles, Flotsam and Jetsam, who had the privilege of their own kiddie pool, said Apicella-Hitchcock. He was also a big hockey fan.

From a distance, you might have assumed he was a “goofy wisecracker, a little cynical and sarcastic,” said Apicella-Hitchcock, but at his core, McLaren was a “thoughtful, warm, and loyal friend.”

McLaren is survived by his brother, Gary McLaren, and his sister, Catherine McLaren. A memorial in McLaren’s honor will be held on Feb. 16, 2024, at 6 p.m. at the Lincoln Center campus’s Lipani Gallery, where several of his films will be screened. Contact [email protected] for more information.

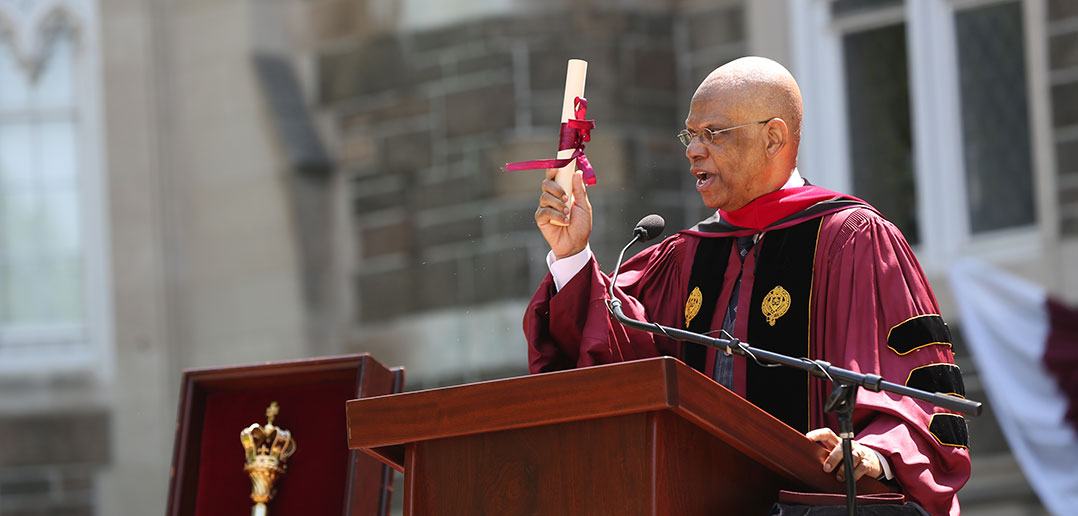

“Fordham joins the people of New York City, and especially the congregants of the Abyssinian Baptist Church, in mourning the passing of the Reverend Dr. Butts,” said Tania Tetlow, president of Fordham. “For more than three decades he was not just the pastor of Abyssinian, but a spiritual and moral leader for New Yorkers and people around the world. Dr. Butts leaves behind a lasting legacy of education, civil rights, and community building. The Fordham community offers its profound condolences to Dr. Butts’ family, friends, and the congregation of the Abyssinian Baptist Church.”

Dr. Butts occupied a special place within the Fordham community. When the University returned to an in-person commencement ceremony this May after a three-year COVID hiatus, it was Dr. Butts who spoke to the assembled crowd of 16,000. In a rousing address, he told graduates that their Fordham education is transformative—a tool to help turn them into leaders of great character.

“One of the great things about character is that it teaches us to nurture our love for beauty. It teaches us to endure to the end, it teaches us to have courtesy for the other,” said Butts, who received an honorary doctorate of divinity at the ceremony. “I don’t mean just opening a door and tipping your hat—I mean recognizing that all men and women are brothers and sisters in this world.”

Fordham’s relationship with Dr. Butts began in the 1970s when he joined the University as an adjunct professor who taught a course in the history of the Black church in America. In the fall of 2021, he was appointed a distinguished visiting professor in support of the Graduate School of Education’s Center for Catholic School Leadership and Faith-Based Education.

Fordham alumna Marlene Taylor-Ponterotto, a medical provider in Harlem, recalled taking Dr. Butts’ class on Black church history in 1975 and reflected on his influence on her throughout her career.

“As a freshman it was one of my first courses, and it inspired me to fully understand the importance of spirituality and how it impacted the lives of African Americans. This message has stayed with me always as I grew to understand how significant his words were,” said Taylor-Ponterotto, who graduated from Fordham College at Rose Hill in 1979. “I am an HIV specialist and when I saw his involvement in the village of Harlem, where I practice now, ensuring that funds and more were in place for these patients, I was again reminded of his wisdom. He will always be one of those professors who taught me valuable lessons which I use each day in my practice.”

Last June, at Dr. Butts’ invitation, Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president emeritus of Fordham, preached at Abyssinian. In his sermon, Father McShane called Dr. Butts “a man for whom the biblical statement ‘Behold, he does all things well’ seems to be tailor-made.”

“He is the kind of preacher whom other preachers don’t only listen to. No. They study the transcripts of his sermons, all of which are nothing less than master classes in the art and craft of preaching,” Father McShane said. “Dr. Butts never tires of reminding us rightly that faith and education together form a modern-day cradle of civilization and the true source of both liberation and redemption.”

Butts delivered powerful sermons for more than 30 years at Abyssinian, focusing on the church’s core values of worship, evangelism, service, and education. He founded and chaired the nonprofit Abyssinian Development Corporation, a community-based organization responsible for over $1 billion in housing and commercial development in Harlem, and was instrumental in establishing the Thurgood Marshall Academy for Learning and Social Change—a public, state-of-the-art, intermediate and high school in Harlem.

A native New Yorker, Dr. Butts graduated from Morehouse College in 1972 and earned his Master of Divinity and Doctor of Ministry degrees from Union Theological Seminary and Drew University, respectively.

From 1999 to 2020, he served as president of the State University of New York (SUNY) at Old Westbury, one of the most racially and ethnically diverse schools in the SUNY system. His leadership led to the college’s largest enrollment ever, the addition of full-time faculty, and the expansion of student support services. The school earned new accreditations and created its first-ever graduate programs during his presidency. He also oversaw the college’s investment of approximately $200 million in capital projects. During his tenure, SUNY at Old Westbury received the Higher Education Excellence in Diversity Award from INSIGHT Into Diversity magazine for 2018, 2019, and 2020.

Dr. Butts’ unshakable belief that education and faith are intertwined was evident when he spoke to the Fordham community from the Terrace of Presidents at Commencement; in his address, he declared that the two are “the Tigris and Euphrates of our redemption, twin rivers at the source of our liberation.”

“Education ought to improve your character, education ought to help you increase your knowledge, and education ought to help you earn a living,” he said.

And while Dr. Butts lamented that “earning and living on the top” has become more popular than “development of character,” he expressed hope that Fordham students will reverse the trend.

“We are tomorrow. You are tomorrow,” he said. He told the graduates that they were examples of those who put character first and that they “represent the hope for America.”

Despite the challenges faced in this country, he said, education is “the tool that will help you to press our nation forward: backward, never; forward, ever.”

]]>“It is heartbreaking to lose someone so young, and so full of joy for life,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “Tessa was what we hope every student to be: kind, intellectually curious, and self-aware. I know the Fordham community joins me in keeping Tessa’s family, loved ones, and friends in their thoughts and prayers.”

Originally from Charlottesville, Virginia, Burns moved with her family to Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Orlando, and Indiana. She attended Carmel High School, where she was a member of several student clubs, including Spanish Club, National Honor Society, and student government. As a member of the student government, she helped to organize fundraising events for a local children’s hospital—the same place where she was treated for her cancer. In one year, the high school students raised more than $453,000 to support pediatric care and research, she wrote in her college application to Fordham.

“I have had the chance to build relationships and mentor fellow patients who are feeling the same way I did and show them how to keep fighting,” Burns wrote. “These moments are times that I will cherish forever.”

Burns’ leukemia returned in October 2021. She underwent treatment from 2021 to 2022 at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan, and she was on medical leave for the spring semester.

“Tessa loved life, she loved meeting people,” said her mother, Jill Burns, adding that she was known to people as “Tessa.” “Every stranger was a friend she hadn’t met yet. She was looking forward to studying abroad in Paris in the spring semester.”

A Foodie Who Loved Sustainable Recipes

In her profile on WayUp, a job site for college students and recent graduates, she wrote about her passion for food culture. In high school, she created a health-food Instagram account, @therawalmond, to encourage herself to eat healthier. Her posts begin in fall of 2019, the same time she started school at Fordham. Over the next three years, she shared vibrant photos about her food adventures in New York City and beyond, including meals from new restaurants and recipes from other food bloggers. She also developed her own recipes, including vegan apple cinnamon tarts. It is clear from her Instagram feed that she loved baking. Her feed is flooded with photos of bread—most notably, pumpkin bread. Her final post, from March 17, features shakshuka from a bistro in Indiana.

Teaching Lessons on Acceptance and Gratitude

The goal of her food blog was to show her peers that it’s not hard to be healthy and that healthy food can be delicious, too, she told The Observer in 2020. But some of her posts take on a more personal tone.

In November 2020, she wrote about the importance of embracing your imperfections. She posted a photo of a discolored scar on her leg from a muscle infection, back when her immune system was weak from leukemia and the chemotherapy that treated her cancer.

“We all have things we dislike about ourselves, but we just gotta accept whatever those things are. … We all just need to look at the things we don’t like about ourselves and appreciate what they’ve taught us,” she wrote.

‘I Would Not Exchange Being Sick for a Blissful Life’

Burns was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia during her sophomore year of high school. Thanks to her support system at school and at home, she was able to graduate on time.

In her college application essay to Fordham, she wrote about her experience with cancer. In the spring of 2016, she was wheelchair-bound with a feeding tube in her nose. She experienced tough treatments, including chemotherapy. But during her cancer treatment, she said she met the most amazing people—“doctors, nurses, friends, strangers”—who inspired her and changed her outlook on life.

“I would not exchange being sick for a blissful life because I grew as a person immensely. The people I met helped me grow and realize that life is about the little things, laughter is the best medicine, you can do anything that you put your mind towards, and positivity changes everything,” she wrote in her personal essay. “Now, I am physically and mentally capable of anything.”

“Tessa loved Fordham,” her mother said. Burns majored in cultural anthropology and minored in fashion studies, according to her mother, who said her academic interests complemented one another. “She was interested in the way culture influenced fashion.”

Burns is survived by her mother, Jill; her father, Robert; sisters Sara and Ana; and brother Niall—she was the youngest sibling. The family will hold a celebration of life for Burns in Carmel, on July 10. Condolences may be sent to R. Cartland, Jill, Sara, Ana, and Niall Burns at 13534 Brentwood Lane, Carmel, I.N., 46033.

“People often take time for granted. We are so busy with our lives that we don’t open our eyes to how other people see the world. Personal experience has taught me that we have a given amount of time to make an impact or change in someone’s life,” Burns wrote in her college application essay. “We can learn so much from each other, we just have to seize our opportunity.”

—Bob Howe contributed reporting.

]]>“Patrick was a young man, and he was full of promise,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, in a statement emailed to the University. “He was a selfless, reliable member of the behind-the-scenes team that keeps the University running and enables the work of Jesuit education to continue, day by day.”

Howe started working at Fordham as a refrigeration engineer in 2014. He was responsible for installing and repairing heating, ventilation, air conditioning, and refrigeration systems at the Lincoln Center campus. But his knowledge of the facilities at Fordham extended beyond his usual job capacities, said his manager, Jedd Applebaum, chief engineer and associate director of facilities operations. Howe was a “jack of all trades” who could run any piece of equipment or building, said Applebaum, and one of the best engineers at Fordham.

“When I knew he was [here], it made my life 10 times easier. If I had something going on, even my boss would say, ‘Is Pat going to be there?’” Applebaum said. “The first person we would grab was Pat.”

Howe went above and beyond his responsibilities, said Applebaum.

“He was already an established engineer, but he was going to the next level of trying to learn the programming of our building management system, which is completely another step. He took advantage of online courses [outside of Fordham] to learn the actual programming,” Applebaum said, noting that he wanted to be able to move up at Fordham.

Howe was not only a hard worker but also a selfless colleague, said Applebaum. During the Christmas season, he signed up for work shifts so that his colleagues with children at home could spend the holidays together, said Applebaum. He was also a smart and confident engineer who taught new employees, but never put on any airs, said Applebaum. And during the height of the pandemic, he always came into work.

“Fordham lost someone who would be here until he retired. He loved this University,” Applebaum said. “I have a 12-year-old, and I hope he grows up like him.”

Howe was born on September 28, 1981, in Valley Stream, New York. He was raised by his parents, Patrick Howe Sr., a senior service technician who worked for a boiler control company, and Donna Howe, a retired bookkeeper, alongside his younger sister, Mary Levin. As a child, Howe was inquisitive, honest, kind, and funny, said his sister. He loved skateboarding so much that when he accidentally broke his wrist while skating, he continued to skate—and coincidentally broke his other wrist just two weeks later, said his father.

Howe was not a big fan of school, said his mother. The only book he loved was Fight Club, a 1996 novel that was later turned into an American film, she said. (His favorite quote from Fight Club was “The things you own end up owning you,” she added.) But he was still a curious child who wanted to know everything about the world.

“He was relentless with his questions. He would ask, ‘Why does it rain?’” his mother recalled. “Everything that he was interested in, he took to the nth degree.”

Howe matured into a devoted son, brother, uncle, and friend who loved to be surrounded by people, said his family. His two nephews loved to wrestle with him and jump on a trampoline together, and they jokingly called him “Uncle Poopypants,” said his sister.

His sense of humor translated to every part of his life, said his family. He was an excellent mimic who could retell stories with flawless facial expressions, and he had the ability to make people laugh, said his mother and sister.

As an adult, he took pride in personal fitness and his tattoos, including a large koi fish on his arm. Howe was also a film buff who loved “dark” and “action-oriented” movies, including the Godfather series and Marvel and DC Universe films, said his family. He recently said that if he hadn’t become an engineer, he would’ve been a movie critic, his mother recalled. “He knew the director, he knew the way it was filmed, he knew what the ambiance was, what they were trying to say,” she said. “He was a lot deeper than most people realized.”

Howe earned his associate’s degree in liberal arts and sciences and liberal studies from Nassau Community College in 2005. He graduated from the Turner Technical School in 2007, where he became certified in working as a refrigerating system operating engineer.

Before he joined Fordham, he held several jobs, including a licensed maintainer at the New York Public Library, where he maintained the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems.

“He stayed there for a number of years, and then he went to Fordham, which he absolutely loved. His job was very important to him,” said his mother, adding that he treasured the friendships he made there.

“He got along with everybody,” his sister said. “He didn’t see skin color or race or ethnicity or religion. He just saw people for people, and he loved everyone—and everyone loved him.”

Howe is survived by his mother, Donna Howe; father, Patrick Howe Sr.; younger sister, Mary Levin and her partner, David Levin; and two nephews, Dylan and Brayden. A wake will be held on Friday, April 15, at the Lieber Funeral Home located at 266 N. Central Ave., Valley Stream, New York, from 2 to 4 p.m. and 7 to 9 p.m.

—Chris Gosier contributed reporting.

]]>“He came to Fordham in July 2020, and during his too-brief tenure brought tremendous intellectual acumen, energy, and gravitas to the role. He was an experienced and capable administrator and a highly regarded historian and public intellectual with a fierce commitment to social justice and the advancement of minority scholars,” Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, wrote in an email to the University community. “We have lost a great soul in Tyler.”

Stovall was a longtime leader in higher education on both the East and West coasts. He started his career as a high school history teacher at the Nichols School in Buffalo, New York, in 1978. He worked his way up in various roles—teaching assistant, instructor, assistant professor, associate professor, professor, and provost—at universities in Wisconsin, Ohio, and California. His most recent positions before Fordham include dean of the Humanities Division and a distinguished professor of history at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and the dean of the Undergraduate Division of Letters and Science at the University of California, Berkeley.

Stovall was a respected historian who inspired scholars with his research and witty, accessible lectures. He was president of the American Historical Association, the oldest and largest society of historians and professors of history in the United States. He authored 10 books and numerous articles in the field of modern French history, and he was particularly interested in race and class, Blackness, postcolonial history, and transnational history. In his latest book, White Freedom: The Racial History of an Idea (Princeton University Press, 2021), which was published just before the Capitol riot of January 6, 2021, he reflected on how our ideas about freedom are shaped by our views of race. For Americans, freedom has always been nearly synonymous with whiteness, he said in a Fordham News interview about his book. In his final published piece—written for The Nation, the oldest weekly magazine in America that was founded by abolitionists in 1865—he wrote about the relationship between democracy and authoritarianism.

On his personal website, he wrote about the importance of history in shaping a better future.

“For me, history is the record not only of how things change, but how people make things change, how they act individually and collectively to create a better world,” he wrote.

In an announcement to the Fordham community, Provost Dennis Jacobs wrote about Stovall’s own place in history.

“Among the first African Americans in the U.S. to achieve prominence in European history, he has provided encouragement and mentorship for other minority scholars to follow in his stead,” Jacobs wrote when Stovall was appointed in 2020.

Stovall arrived at Fordham on July 1, 2020. As dean of GSAS, Stovall encouraged student-faculty collaboration and worked with alumni to strengthen career and mentorship networks. He enhanced existing programs, including GSAS Futures and Preparing Future Faculty, and developed new ones, including an alumni mentoring network, said Eva Badowska, Ph.D., dean of the faculty of arts and sciences and associate vice president for arts and sciences. In addition, he worked on strengthening the undergraduate and graduate 4+1 programs, in collaboration with the deans of Fordham College at Rose Hill and Fordham College at Lincoln Center.

When he first arrived at Fordham, he immediately focused on student needs, especially funding opportunities for students who were experiencing food insecurity and income scarcity during the pandemic, said Joanne Schwind, assistant dean of GSAS’s office of academic programs and support. Stovall also strived to make the University a more welcoming place, especially for students and alumni of color.

“I was literally hired the same week that George Floyd was murdered,” Stovall said in a 2020 online discussion with other deans about anti-racism efforts at Fordham. “For me, being an African American dean at Fordham has called up both opportunities and responsibilities. It has meant that I have to think about what other members of the African American community are experiencing and the ways in which my position can be an asset to that community and, through that community, an asset to Fordham as a whole.”

Seven months later at a follow-up forum, Stovall contributed to a conversation about changes in the curriculum, the recruitment of more faculty and students of color, and other efforts to address racism on campus. In addition, he helped to educate the Fordham community about the significance of Juneteenth in a short video and reflected on the value of diversity in a university community in another video last summer.

“People often talk about diversity as being important for marginalized communities … But I want to emphasize that certainly at Fordham University and I think in our society as a whole, diversity is something that benefits all of us. Being exposed to people from different backgrounds, being able to interact with people with different experiences is something that we all learn from and makes all of our lives better,” he said in the video.

Stovall worked closely with Rafael Zapata, Fordham’s chief diversity officer, on several anti-racism and diversity initiatives.

“We collaborated on co-hosting a University-wide Faculty of Color and Allies gathering last spring that had about 85 attendees and generated a great deal of excitement, with a planned follow up for late January 2022. We were also working on BIPOC administration and staff development within Arts and Sciences,” Zapata said.

“We were doing a lot, and I just remember him saying, ‘Whatever you need, count me in.'”

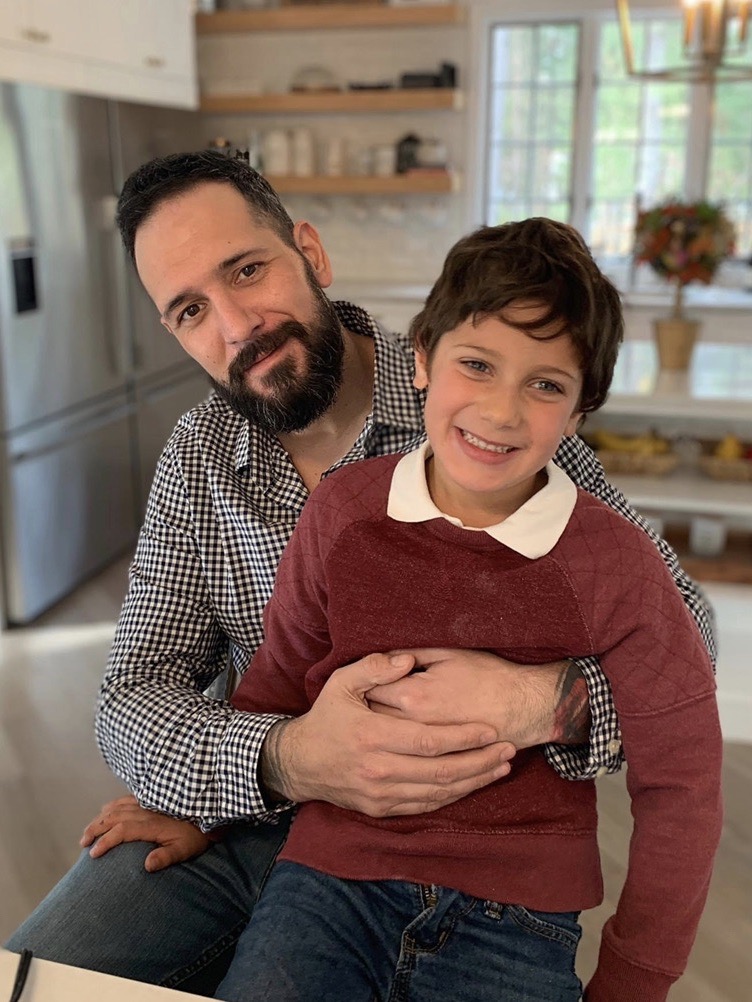

Zapata said he and Stovall become neighbors in Hamilton Heights and enjoyed numerous lunches and dinners together. “I even ran into him with his son, Justin, at a spot near City College I’d taken him to previously—the way you run into good people at your favorite spots.”

In one of Stovall’s last messages that was set to go out to the University community, he reflected on his time at Fordham.

“Having spent my first year at Fordham on a nearly deserted campus in 2020, it has been deeply gratifying to see life return to the classrooms, lawns, and buildings of Rose Hill and Lincoln Center. At the same time, however, this fall has made it abundantly clear that the coronavirus will not disappear so easily … In spite of these challenges, our GSAS students and alumni have continued to display the perseverance and innovation that so attracted me to Fordham,” Stovall wrote in an email to GSAS alumni this December. “We will always face challenges, but I am confident that the members of the GSAS community will play an important role in meeting and overcoming them, now and in the future.”

Stovall was born in Gallipolis, Ohio. His father, Tyler Edward Stovall, was a child psychologist; his mother, Barbara Fuller Stovall, was the director of the South Side Settlement House, a social and economic justice-focused community center. He earned a bachelor’s degree in history from Harvard University and two separate degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Madison—a master’s degree in European history and a Ph.D. in modern European/French history. In a well-detailed online biography, a former mentee chronicled the most telling details of Stovall’s life and said Stovall taught him that “history can and should be a political act, essential to our struggles to make the world a better place.”

His impact at Fordham is clear, said Schwind, although his time at the University was short.

“Tyler was a wonderful leader, boss, and dean who inspired his staff to pursue their goals with a focus on equity and inclusion, and a vision toward the future of GSAS and its students,” she said. “Even though his time with GSAS was brief, Tyler’s kindness and compassion toward his colleagues, staff, and students will have a long-lasting impact on us all.”

Stovall is survived by his wife, Denise Herd, their son, Justin, and a sister, Leslie Stovall. Information on services will be provided when available.

]]>“Jonathon was a caring and compassionate educator who had the kind of multilayered career that one can only marvel at,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, in an email to the University community. “He was thoughtful and creative, with a talent for drawing connections among disciplines.”

Appels taught in Fordham’s English, African and African American studies, anthropology, dance, history, communication and media studies, Middle East studies, theology, and visual arts departments, as well as the religious studies, comparative literature, and urban studies programs, from 1996 to 2002 and 2009 to 2021. He offered a colorful mix of courses, including “Madness and Literature” and “LGBT Arts and Spirituality: Mystics and Creators,” mostly at the Lincoln Center campus.

“His mind was eclectic and his education and curiosity was unmatched,” said Anne Fernald, Ph.D., professor of English and women, gender, and sexuality studies. “Endlessly curious, he always had a new story of the latest lecture or performance he had attended. He was a wonderful storyteller, with a rich laugh. He took me out to a vegan restaurant once, hoping to encourage me in more healthy habits. He was always cold and wandered the halls draped in wonderful scarves.”

Appels was a scholar, poet, musician, sculptor, and art critic who conducted research in 20 countries, largely in Europe; he was also a member of nine humanities associations.

“He had a very probing mind, and he was very good at connecting the dots between various disciplines and departments,” said his husband, David LaMarche. “He was a very animated and inquisitive person with strong opinions, but not rigid … a free spirit and sort of counterculture, since the time that we were born in, the early sixties, and a sensitive man who loved every branch of the arts.”

His First Love

But what most academics weren’t aware of, said his husband, was his love for dance.

“He loved teaching, but his first love was probably choreography,” LaMarche said.

Appels was a dancer and choreographer who founded his own dance company, Company Appels, in 1979. He performed across the country and the world, from the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City to international stages in France, Germany, and Portugal. He choreographed modern dances for scores of performers, principally graduates of the Juilliard School, SUNY Purchase, and North Carolina School of the Arts. One of his favorite courses he taught at Fordham was part of the Ailey/Fordham BFA Program in Dance, run jointly with the Ailey School, said his husband. Even off stage at more casual venues, you could find him dancing.

“He loved disco dancing and he loved to dance, even into his sixties. If we ever went to a gala party or something like that, he’d always be on the dance floor, wild,” said LaMarche, a pianist who first met Appels at a dance class in San Francisco.

Appels’ passion for the arts was recognized worldwide. In 1998, he was awarded a Fulbright to teach modern dance at the National Dance Academy in Hungary. (He received another Fulbright to study the archives of a famous philosopher in Belgium in 1991.) In addition, he received an artist fellowship from the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts and a William Como Award from the New York Foundation for the Arts.

In a 2014 reflection, a Fordham alumnus praised Appels for showing him the beauty of dancing through his course called Lincoln Center Arts.

“I never considered dance to be very interesting, running the other way when friends would suggest going to the ballet … I now found myself discussing Balanchine, Paul Taylor, and Dance Theater of Harlem with anyone who would listen,” wrote Jason McDonald, who took the course as a Ph.D. student.

‘Now Keep That Big Smile’

Appels was a thoughtful instructor who wanted his students to take away something meaningful from his classes, said Thomas O’Donnell, Ph.D., co-chair of Fordham’s comparative literature program and associate professor of English and medieval studies.

“Jon really wanted his students to become exposed to very different ideas. He was a very curious and open-minded person, and it seemed that his lessons as a result were full of that same spirit,” O’Donnell said. “He cared about his students very deeply. For every student that I would talk to him about, he had some story or insight about their biography and who they were. He really wanted to get to know the students so he could help them better.”

He loved speaking with students about their work over the phone, said LaMarche. Before their calls ended, he left them with a unique message.

“He ended almost every phone call with a student by saying, ‘Now keep that big smile,’ which I thought was so cute,” LaMarche said, chuckling. “You can’t see someone smile over the phone, but he would always say that to them.”

An ‘Off-the-Grid Educational Experience’

Appels was born on May 17, 1954, in Falfurrias, Texas. His father, Robert C. Robinson, was a sales executive for oil companies and a financial planner; his mother, Patricia Robinson, neé Hosley, was an elementary school teacher. When he was a child, his family frequently moved because of the nature of his father’s job, said LaMarche. He lived in Nigeria and Libya and later settled in California.

“He was exposed to a lot of different cultures as a youngster … He got his B.A. at Western Washington University at a college called Fairhaven College, which was a very experimental educational institution at that time,” said LaMarche. “That started his off-the grid educational experience.”

Appels earned a bachelor’s degree in art and society from Western Washington University, a master’s degree in music from Mills College, a master’s degree in poetry from Antioch University, and a Ph.D. in comparative literature from the City University of New York.

Outside of Fordham, he taught undergraduate and graduate students at Columbia University, Cornell University, Princeton University, Rutgers University, and his alma mater Western Washington University. He enjoyed yoga, pilates, gyrotonics, acupuncture, and other forms of Eastern medicine and healing. Instead of ironing his shirts and wearing a suit jacket like many professors, he preferred a loose and casual style, LaMarche said. He was a spiritual man who loved nature, especially walks through the woods and summers spent with LaMarche in Ithaca, where they swam in waterfalls, gorges, and lakes. He disliked technology, especially computers—in fact, he never owned one, said LaMarche, who managed his husband’s online accounts.

In addition to LaMarche, Appels is survived by his father, Robert; brother, Robert H. Robinson and his partner, Ilona Robinson; and his sister, Carol House, her husband Roger House, and their son Josiah. A memorial service will be held for Appels sometime early next year, said LaMarche.

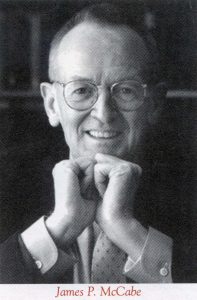

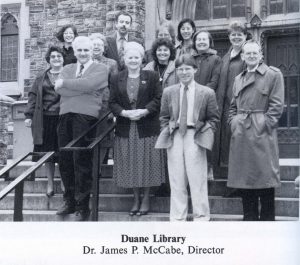

]]>“Jim was a dedicated University librarian and administrator whose can-do spirit served the University well during a period of expansion and growth,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “He brought Fordham from an era of card catalogs to the full splendor of the information age. Thanks to his efforts, our students and faculty may draw from a far deeper well of information in pursuit of learning and scholarship.”

McCabe became the director of libraries on August 13, 1990. Until he retired in 2012, he helped Fordham libraries reach new heights—literally. He was an integral part of the design and construction process for the William D. Walsh Library, a five-floor modern Gothic style building that has housed more than 1,000,000 volumes since it was completed in 1997. The building was classified as the fourth largest library in New York in 2013 and featured in The New York Times.

“Jim McCabe’s strong vision for the future combined with his deep knowledge and respect for traditional practices made him the perfect person to lead the Fordham libraries into the 21st century. But Jim was much more than that,” said Linda LoSchiavo, director of libraries at Fordham, who succeeded McCabe. “A gentle, gracious man, with a quick sense of humor, he was esteemed and admired by his staff, his colleagues at Fordham, and by the academic library community as a whole. The University has lost a quiet hero, and those of us fortunate enough to work closely with him have lost a friend.”

Maryanne Kowaleski, Ph.D., retired Joseph Fitzpatrick, S.J. distinguished professor emerita of history and medieval studies, recalled McCabe’s leadership when Fordham moved its collections from Duane Library, which used to be the main library for the Rose Hill campus.

“Jim McCabe came to Fordham at a crucial juncture, when he oversaw the complicated move to the new Walsh Library and facilitated the transition to electronic resources that we take for granted today,” Kowaleski said. “He was a kind and gentle man who led by example, taking his turn in the labor involved in moving the collection. He also went out of his way to meet and socialize with faculty, working to open up fruitful lines of communication between Fordham’s teachers and librarians.”

‘Let’s Do It’: A Librarian and Leader in the Digital Age

McCabe was a leader in the university library community during a time when technology began to dramatically change the ways libraries worked. At the beginning of the new millennium, he introduced the complete automation system to Fordham’s libraries, which included the electronic catalogue system and the library’s back-office operations. This helped librarians work more efficiently and gave students quicker access to resources. In addition, he helped promote one of the library’s most popular services, the electronic reserve room software. Similar to the BlackBoard Learn system currently used by faculty and staff, the electronic reserve room software was used to help faculty create course pages and upload resources for their students.

“The immediate, enthusiastic acceptance of electronic reserves is proof that it is a program whose time had come. It is a fine example of how the Internet can make our lives and work a little easier, and save time and energy,” he wrote in a 2000 piece for Inside Fordham Libraries.

In addition, he served as a link between Fordham and New York Libraries in his role as president of two local library organizations. He served on the Metropolitan New York Library Council’s Board of Trustees, where he helped foster conversations about important library and information issues, and on the Historical Preservation Commission for Westfield, New Jersey, where he helped to preserve the town’s historical sites and landmarks.

McCabe was not only a librarian, but also an author. He wrote Critical Guide to Catholic Reference Books (Libraries Unlimited, 1971), a series of annotated entries on topics related to the Catholic Church, including liturgy, social sciences, and literature.

“[He brought] digital resources of bewildering variety to library users within and without our library buildings. He has done this while substantially increasing the size and scope of our print collections, improving staff morale, increasing the hours and quality of library service to library users, and winning the respect, admiration, and affection of the Fordham community,” read a citation in a 2010 convocation booklet that recognized 20 years of his service to Fordham. “Whenever he encounters an opportunity to provide a new service or improve an old one, his reaction has been, ‘let’s do it.’”

In the early 2000s, he named two hawks that once frequented the Rose Hill campus and the New York Botanical Garden. The first hawk was named Rose after the Rose Hill campus; the second hawk was named Hawkeye Pierce, in honor of the character played by Fordham alumnus Alan Alda on the M.A.S.H. television series.

‘It Isn’t Raining in Our Hearts’

McCabe was born on May 24, 1937 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Felix and Josephine McCabe. His father was a lineman for a telephone company and his mother was a nurse. He graduated summa cum laude from Niagara University in 1963 and earned three graduate degrees at the University of Michigan: a master’s in English literature, a master’s in library science, and a doctorate. For more than two decades, he served as library director at Allentown College of St. Francis de Sales in Pennsylvania, now known as DeSales University, where he oversaw the conceptualization and construction of a new library facility. Right before his appointment to Fordham, he served as the acting library director for Muhlenberg-Cedar Crest Colleges Libraries in Pennsylvania.

His friend for nearly 40 years, Romain Frugé, said McCabe was a beloved member of the theatre community at DeSales University, where he manned the lighting booths during shows and served as an academic mentor and confidant for students. McCabe was also a staunch supporter of students’ work. He flew to London and Japan to watch Frugé perform in several musicals, said Frugé. And no matter where he went, McCabe had a positive outlook on life.

“Whenever it was raining, Jim would say, ‘Well, it isn’t raining in our hearts,’” said Frugé, who was a student at DeSales University, where McCabe worked as library director. “He was always a real positive force.”

McCabe never had children of his own, but he was close to his four siblings and their children. For many years, he spearheaded an annual family picnic in Manhattan, said his niece Jennifer Carlin. He loved everything about the city, especially cheap tickets to Broadway shows, and he walked like a classic New Yorker at 10 miles per hour, said his nephew Felix Carroll. And he always appreciated the little things.

“He gave me a really great piece of advice when I was in my early 20s,” Carroll said. “I was moving all over the place, and I couldn’t settle on anything … He told me to stop and take delight in the world. We can be worried, but we’re supposed to find joy, too, and that’s found in everyday things.”

McCabe is survived by two siblings, Aileen McClure and John McCabe, and numerous nieces and nephews; he is predeceased by two siblings, Francis McCabe and Ann Carroll. A funeral Mass will be held on Sept. 24 at 11 a.m. at St. Ephrem Catholic Church located at 5400 Hulmeville Road, Bensalem, Pennsylvania, 19020. The Mass begins at 11 a.m., but family and friends are invited to gather at the church an hour earlier. Interment will follow at Resurrection Cemetery.

The funeral service will also be streamed, beginning at 10 a.m. on Sept. 24. To obtain the link to view the service, contact Jean Walsh, senior executive secretary at the Walsh Library, at [email protected] by Sept. 23 at 5 p.m., latest. You can view live or at your own convenience.

In lieu of flowers, donations in McCabe’s honor may be made to the book fund at Fordham University Library.

By check: Payable to Fordham University Library

Attn. Linda LoSchiavo

Director of Libraries

Walsh Library, Suite 219

441 East Fordham Road

Bronx, NY 10458

Online: www.fordham.edu/give. Several funds are listed. Click OTHER, then indicate “Fordham University Library, in honor of James McCabe.”

]]>