“Carol Robles was a dynamo her entire life,” U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor said in a statement. “She devoted herself to public service and made a noteworthy difference both in the lives of Latinos and all New Yorkers. Her passing is a tragedy for her family and all of us.”

A 1983 graduate of Fordham College at Lincoln Center, Robles-Román served as deputy mayor for legal affairs during Michael R. Bloomberg’s three-term tenure as mayor, from 2002 through 2013. She was the highest-ranking Latina in city government at that time and the first woman ever to serve as counsel to a New York City mayor.

From City Hall, she oversaw more than a dozen agencies. Her accomplishments include launching the city’s Family Justice Centers to provide free, confidential, and comprehensive assistance to survivors of domestic violence. She also expanded the city’s language-translation services to better meet the needs of non-native English speakers. And she was instrumental in creating the Latin Media and Entertainment Commission to help “bring the best in Latin media and entertainment productions, businesses, and jobs” to the city.

After serving in the Bloomberg administration, she led two national civil rights organizations: Legal Momentum—the Women’s Legal Defense and Education Fund, and the Equal Rights Amendment Coalition/Fund for Women’s Equality. In recent years, she had been general counsel and dean of faculty at Hunter College. She also was a longtime member of the City University of New York Board of Trustees.

“Carol Robles-Román dedicated her life to public service and to making our city and country more equal and just,” Bloomberg wrote in a statement, citing her “groundbreaking work to make the city more accessible to our … immigrant and disabled communities, and to stop domestic violence and human trafficking.”

In a 2015 profile in Fordham Magazine, Robles-Román described her approach to identifying societal problems and mobilizing both the political will and the means to fix them.

“Part of my ethos is being a disruptor—in a nice, good way,” she said. “It’s about creating strategic partnerships to make change happen.”

‘Women Can Have a Powerful Voice’

Robles-Román was born in East New York, Brooklyn, on August 27, 1962. Her parents, Emilio and Inéz Robles, owned an insurance brokerage and travel agency, and they were engaged with multiple local civic groups focused on voter registration, housing, and health care, among other issues. They had migrated to New York City from their native Puerto Rico in the mid-1950s, and in the early 1970s, they moved the family to Howard Beach, Queens.

“My mother raised six children—five girls—so it was particularly important to her to teach us, as women of color, that women can have a voice and can have a powerful voice,” Robles-Román once said. “Many women never learn that. That’s the gift she gave me.”

A Puerto Rican Power Couple

After graduating from Stella Maris High School in 1979, Robles-Román enrolled at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, where she majored in political science and media studies.

“I felt very, very comfortable speaking in my own voice and being assertive, and in pursuing my joint passions: civics issues and writing,” she told Fordham Magazine in 2002.

In an international law class, she introduced herself to Nelson Román, FCRH ’84, a fellow student of Puerto Rican descent who would become her husband in 1991. Román, who is now a federal judge in the Southern District of New York, worked as a police officer in the Bronx while he was enrolled at Fordham. He told her what he witnessed while responding to domestic violence calls, and the stories he shared left her bothered but determined to help. She researched best practices for handling such incidents and published her work in a Fordham pre-law journal.

“Ever since then, domestic violence and the treatment of women has been an issue that she’s held very close to her soul,” Román told Fordham Magazine in 2015.

A Champion of Sonia Sotomayor

After graduating from Fordham, Robles-Román worked as a paralegal and eventually earned a J.D. from New York University. In the mid-1990s, she met Sonia Sotomayor, then a federal district court judge, through the Puerto Rican Bar Association. Like many young lawyers in the bar association at the time, she came to regard Sotomayor as a mentor.

“She’s a very warm woman, she’s a very nurturing woman, and she also shared her substantive legal intellect with us very early on,” Robles-Román told CNN in 2013.

In the late 1990s, when Nelson Román was president of the Puerto Rican Bar Association, he and Robles-Román helped lead a grassroots campaign to get a Latino justice on the Supreme Court. Sotomayor was on their short list.

A decade later, in May 2009, when President Barack Obama nominated Sotomayor to serve on the nation’s highest court, Robles-Román helped prepare Bloomberg to speak at a congressional hearing in support of her nomination. Three months later, she became the first Latina Supreme Court justice in U.S. history.

“I felt like this is the message Judge Román and I had been sending our whole lives,” Robles-Román said in 2010. “We have excellent Hispanic judges and attorneys, and it feels like it’s been our job to shine a light on that.”

Prior to joining the Bloomberg administration, Robles-Román served as a senior attorney to a family court judge and as special counsel and eventually director of public affairs for the New York State Unified Court System, where she focused on bias matters, among other issues. She also served as a New York state assistant attorney general in the state’s civil rights bureau.

A Mentor to Young People

During her tenure as deputy mayor of New York City, Robles-Román created what she called her Girl Power School talk, which she presented primarily to middle and high schoolers. She encouraged them to focus on the steps—like writing a resume, finding mentors, and developing a network—that will lead them from the classroom to careers of influence.

“Many young women think that people walk around with tags on them that say, ‘I’ll be your mentor.’ I help them empower themselves to say, ‘Hey, I like that teacher. … I’m going to make an appointment and ask that teacher to mentor me … and to give me advice and to help me as my career proceeds,” she told CNN.

In the 2015 Fordham Magazine interview, she added another piece of advice she often shared with young people: “Don’t be shy,” she said. “Do. Not. Be. Shy.”

Robles-Román is survived by her husband, Nelson; their two children, Ariana and Andrés; four sisters; and four nieces and nephews.

]]>

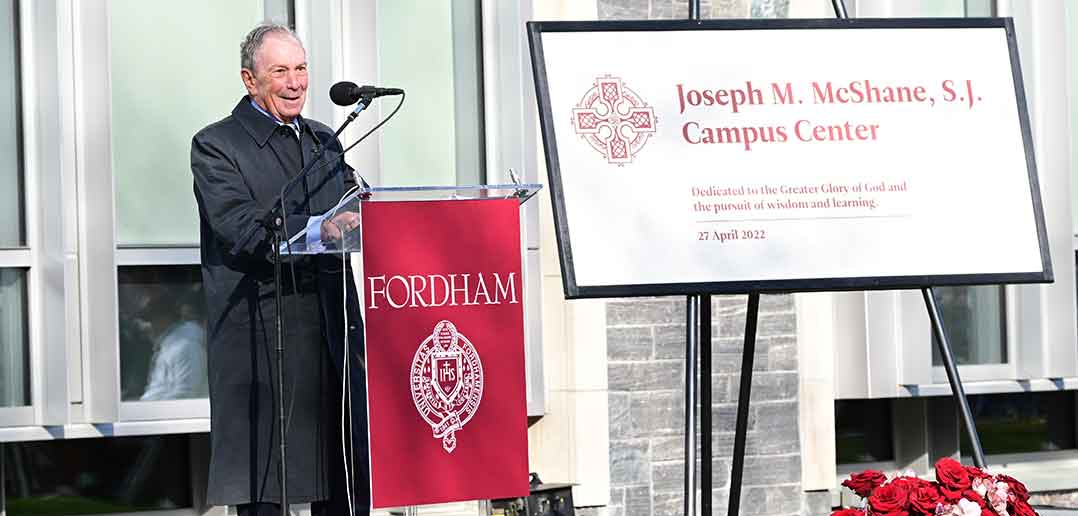

On April 27, Fordham honored outgoing president Joseph M. McShane, S.J., with a ceremonial naming of the Rose Hill campus’ newly renovated campus center.

On April 27, Fordham honored outgoing president Joseph M. McShane, S.J., with a ceremonial naming of the Rose Hill campus’ newly renovated campus center.

The outdoor dedication ceremony, held in front of the gleaming four-story addition that opened in February, drew hundreds of students, faculty, staff, and friends to the official ribbon cutting of the newly christened Joseph M. McShane S.J., Campus Center.

David Ushery, anchor at NBC 4 New York and a 2019 Fordham honorary degree recipient, emceed the ceremony, which included special guests Michael Bloomberg, former mayor of New York, the Honorable Nathalia Fernandez of the New York State Assembly, and His Eminence Archbishop Elpidophoros of America, Primate of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America.

‘Only in New York’

Bloomberg reflected on how he met Father McShane shortly after he was elected mayor in 2001.

“I came to see what an exceptional leader Joe really is. His mind is always racing, his drive is always relentless, his compassion is always boundless, and his Irish wit is always on,” said Bloomberg, who also spoke at the ribbon-cutting for Fordham’s Law School building in 2014.

Speaking from the podium on Wednesday as the wind howled, he joked that ‘Only in New York could a Jewish guy around the corner from a building honoring an Italian football coach celebrate an Irish priest.”

He said he was grateful for his contributions that extended beyond the campus gates. When Bloomberg formed a committee to consider revisions to the city charter, Father McShane accepted his invitation to join, he said. When he launched Bloomberg Philanthropies, Father McShane was one of the first people he approached to join the board. And when Bloomberg Philanthropies launched the American Talent Initiative to push top universities to recruit more students from lower-income families, Father McShane served on the steering committee.

“The common denominator in everything Joe does can be summed up in one single word, and that is service, especially to young people. This wonderful new campus center, rightly named in his honor, certainly testifies to that.”

A Legacy of Transformation

In his 19 years as president, Father McShane is credited with overseeing the investment of $1 billion in infrastructure and raising more than $1 billion in funds for the university.

In addition to the campus center, other capital projects that are part of his legacy include Hughes Hall, the Rose Hill home of the Gabelli School of Business; Campbell, Salice and Conley residence halls; and the Museum of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Art in Walsh Family Library. At Lincoln Center, he led the creation of the dramatic 22-story Fordham Law School and residence hall, which opened in 2014.

During his tenure, the University also established the Fordham London campus, increased financial aid from $78.3 million to $315.1 million, increased the number of endowed faculty chairs from 23 to 71, and this past year, recruited the largest, most diverse class in its history.

Robert Daleo, chair of Fordham’s Board of Trustees, opened the ceremony with a reading of a letter from President Joseph Biden, who hailed Father McShane for having “led the university with faith, dedication, and love through unprecedented challenges and an ever-changing world.”

‘The Modern Heart of University Life’

Daleo noted that it was fitting that the University should name the center, which was originally constructed in 1959, after Father McShane.

“The McGinley Center was a structure that was sturdy, functional, and met the needs of its time, but has now been transformed into the beautiful, modern, heart of University life, and a fitting place for our stellar students, faculty, and staff to gather, eat, play, and learn,” he said.

The ceremony also featured two graduating students, Thomas Reuter, the president of the United Student Government at Rose Hill, and Patricia Santos, vice president of the Commuting Student Association at Rose Hill.

Reuter highlighted the building’s Career Center, Campus Ministry offices, and areas for student involvement. He also noted that the Ram Fit Center showcases the importance of holistic health, while spaces such as the lounge are now filled with laughter, reflection, and the occasional game of pool.

“The space allows us to become what Father McShane envisioned for us: to be people for others, students interested in seeking the magis, understanding and celebrating diversity, developing more informed perspectives, and becoming people of character, formed by the Jesuit tradition,” he said.

Santos said that for commuters, the center is not just a physical structure, but a home for “an intentional community that sets the highest standards of academic, social, moral, and spiritual excellence. “

From the top floor, she said, one can reflect on both Fordham’s Catholic identity and its connections to New York City, thanks to its depiction of the Stations of the Cross and its views of the surrounding area.

“It reminds us that we are blessed with opportunities to learn from our neighbors and contribute to their well-being. Today, the campus center serves as a unifying force in the life of a university that honors each individual and values diversity,” she said.

A Mass of Thanksgiving

The afternoon began with a Mass of Thanksgiving at the University Church led by John J. Cecero, S.J., vice president for mission integration and ministry. Father McShane served as a co-celebrant, along with Thomas J. Regan, S.J., GSAS ’82, ’84, superior of the Fordham Jesuit Community, and fellow Fordham Jesuits. Monsignor Thomas J. Shelley, Ph.D., professor emeritus of theology, served as homilist and Archbishop Elpidophoros presided.

In his homily, Monsignor Shelley, author of Fordham, A History of the Jesuit University of New York: 1841–2003 (Fordham University Press, 2016), credited Father McShane with personifying the idea of cura personalis, or care for the whole person.

“If you’re looking for a monument to Joseph McShane, look around you,” he said.

‘A Dream Machine’

Before leading a group in a ribbon-cutting, Father McShane insisted that the focus of the celebration be on the whole community.

“This is about Fordham, a place that is an extraordinary place, where miracles happen every day, a place where character is formed, hopes are born, and talent is challenged,” he said.

“That is what we are about. We’re a dream machine, in a certain sense, and we unleash great people in an unsuspecting world, people who know to ask the right questions. That’s our gift to the world.”

Watch the whole dedication ceremony here. Read tributes submitted in honor of Father McShane here, and watch a tribute video for him below.

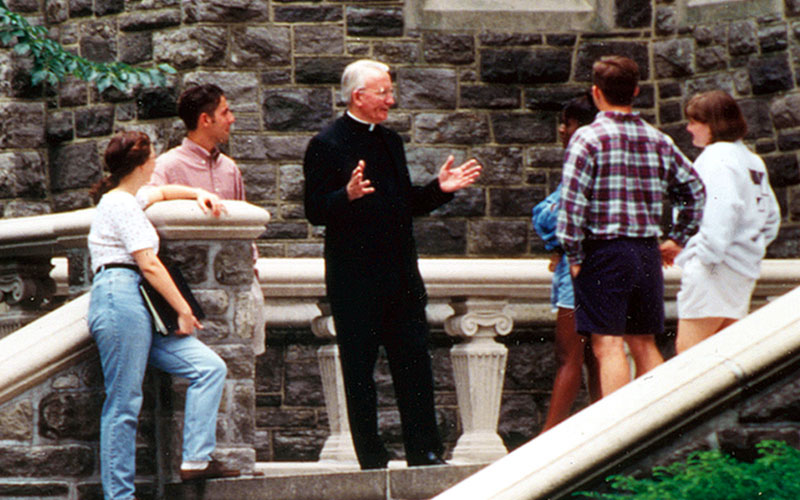

]]>Father O’Hare succeeded James C. Finlay, S.J., on July 1, 1984, to become the 31st president of Fordham University. He held that position for 19 years, making him the longest-serving president in Fordham’s history when he stepped down on June 30, 2003. His tenure marked a period of dramatic growth for Fordham: Applications soared in number; the student body grew academically stronger and more diverse; residential and academic space expanded; and the University exceeded the goal of its first comprehensive fundraising campaign, the crowning achievement of which was the creation of the William D. Walsh Family Library on the Rose Hill campus.

“Having served as Fordham’s president for some time—though not as long as Father O’Hare—I have some insight into, and a deep appreciation for, how gifted he was as a leader, a communicator, and a pastor,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., who succeeded Father O’Hare as president of Fordham. “He placed all of his considerable intellect, integrity, and vision in service of the University, and in doing so transformed Fordham into a powerhouse of Jesuit education. We will miss his wisdom, steady counsel, and warm wit.”

Robert D. Daleo, GABELLI ’72, chair of the University’s Board of Trustees, said the Fordham community owes Father O’Hare “a debt of gratitude for his long and singular service.”

“Father O’Hare led the University for 19 years, and despite some tough financial times, began Fordham’s rebirth as a national university,” he said.

Bronx Roots

A bit of an outsider to academia, Father O’Hare was working as the editor in chief of America, the Jesuit journal of opinion, when he was recruited for the presidency by Fordham’s Board of Trustees.

But the son of first-generation Irish Americans was hardly an outsider to Fordham, the Bronx, or to Catholic education. He was born on February 12, 1931, to Joseph, a New York City mounted police officer, and Marie, a schoolteacher, who raised their family in the close-knit Irish community of Tremont, just two miles from the Rose Hill campus. He attended Regis High School in Manhattan.

In a video tribute to Father O’Hare when he received the Fordham Founder’s Award in 2003, friends, teachers, and siblings recalled the young Joe O’Hare as a well-loved classmate with an easy demeanor, a straight-A student, and a natural storyteller. Although his exploratory forays into theater and basketball at Regis met with success, it was the priesthood that ultimately called to him: Upon graduating from high school in 1948, he joined the Society of Jesus.

Jesuit Formation

That decision, Father O’Hare told The New York Times, was largely inspired by the work of John Corridan, S.J., and the labor priests of the 1940s New York waterfront. “It’s not an otherworldly kind of spirituality,” Father O’Hare said of the Jesuits’ active faith. “It’s the kind very geared to involvement in the present time.”

The young Jesuit-in-training was sent to the Philippines, where he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Berchmans College in Cebu City. From 1955 to 1958 and again from 1967 to 1972, he served on the faculty at Ateneo de Manila University.

Edmundo Martinez, S.J., recalled being a student of Father O’Hare’s in the 1950s.

‘Those were heady days of youth’s idealism for the search of truth, and goodness, and beauty—ideals that rubbed off on us principally, for myself at least, from Joe O’Hare,” said Father Martinez, co-founder, chaplain, and teacher at the Ingenium School in the Philippines. “Like Socrates and his friends, we would sit around in class and discuss such topics as the medieval universities, with Joe leading us on to ever deeper levels and ever wider ranges of meaning.”

Between teaching posts, Father O’Hare returned to the United States, earning licentiate degrees in philosophy and theology in the early 1960s from Woodstock College in Maryland and a doctorate in philosophy from Fordham in 1968. He was ordained a Roman Catholic priest in 1961 in the Fordham University Church.

Fordham Presidency

Sixteen years after his doctoral studies, he left his post at America and was back at Fordham—this time in the Office of the President.

“He made the transition seamlessly,” said Leo O’Donovan, S.J., president emeritus of Georgetown University. “At a time of major discussion between the Vatican and American Catholic universities on the mission of Catholic education,” he said, “he was one of the foremost advocates of fidelity to both true Catholicity and true university freedom of thought and research.”

His presidency took shape just as the Bronx itself was undergoing an economic and cultural comeback from its worst period of blight. Under Father O’Hare’s leadership, Fordham experienced a comeback too. In two decades, the school’s growth exceeded national trends, moving from a school largely attended by commuters to a university with a vibrant campus life and an increasingly national and diverse student body. The number of undergraduate applicants tripled.

The school’s endowment rose from $36.5 million to $271.6 million, enabling the addition of approximately 1.1 million square feet of academic and residential space, and the renovation of more than 1 million square feet of existing space on the Lincoln Center and Rose Hill campuses. Four new residence halls were built at Rose Hill, including Millennium Hall, opened in 2000 and later renamed O’Hare Hall. The Lincoln Center campus saw the addition of its first residence—the 20-story McMahon Hall—in 1993.

In 1991, the University’s sesquicentennial year, Father O’Hare announced the launch of a $150 million fundraising campaign—the largest of its kind at the time for a Jesuit university. Nearly one-quarter of all alumni contributed, and more than two-thirds of funds raised came from individuals, many of whom had no previous connection to the University. The campaign helped to create 170 endowed scholarships as well as several new faculty chairs. Fordham surpassed its goal by $5.6 million.

One of the campaign’s many successes—and one of Father O’Hare’s outstanding legacies—was the construction of the Walsh Family Library, a world-class facility that opened in 1997 at Rose Hill and was subsequently ranked No. 6 in the country in the Princeton Review.

Robert Campbell, GABELLI ’55, former vice chairman of Johnson & Johnson who served as Fordham’s board chair during much of the 1990s, said that as a leader, Father O’Hare showed a “willingness to take risks.” He recalled Father O’Hare telling him that Fordham had been talking about building a new library for 50 years.

“He went to the board with it and they went along,” he said. “It was very symbolic, because it was tied to a major campaign and because it said Fordham’s on the move. New York was a tough place, and we were there to compete with anyone.”

Campbell said Father O’Hare’s determination was complemented by “his sincerity and his sense of humor that always came through.”

As a native New Yorker and a Jesuit committed to social justice, Father O’Hare saw great potential in a stronger unification of Fordham’s two New York City campuses, which he helped achieve through the restructuring of faculty and adoption of a shared core curriculum. He felt that each location had much to teach students.

“Fordham men and women have found in the city rich cultural resources, but also daunting moral and social challenges, soaring celebrations of the human spirit here at Lincoln Center, but also a summons to service in the neighborhoods of the Bronx. These different faces of the city engage the classical Renaissance humanism of Jesuit education, but also the new Jesuit humanism that adds to this classic ideal the urgency of education for justice,” he said at Fordham’s 160th Anniversary Dinner at the New York State Theater in 2002.

Influence and Reach

Father O’Hare’s influence extended far beyond Fordham and New York City in many ways, not least of which are the accomplishments of those who worked for him.

“In his 19 years as president, he helped mentor many Fordham colleagues into their own presidencies, including me,” said Fordham Trustee Donna Carroll, Ph.D., University secretary under Father O’Hare and current president of Dominican University in Chicago. “He said something to me once that guides me still: ‘You choose to see the limits or the possibility in Catholic higher education. What you choose determines how you lead.’”

Demonstrating a commitment to Fordham’s many Catholic traditions, Father O’Hare helped establish Fordham’s Center for American Catholic Studies, the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs, and the Laurence J. McGinley Chair in Religion and Society, for which he recruited Avery Dulles, S.J. (before he was elevated to cardinal). He made many international trips in service to Fordham and the Jesuits, traveling to 26 countries during his presidency.

Principled Civic Leadership

Father O’Hare devoted equal time to forging Fordham’s relationships with New York City. In 1988, Mayor Edward I. Koch made him the founding chair of the New York City Campaign Finance Board, one of the nation’s groundbreaking models for campaign finance reform. So ethical was Father O’Hare’s leadership, said Mayor Koch, that the board even fined his mayoral staff for errors made in campaign contribution reporting. Father O’Hare held the position for 15 years. In late 1993, Mayor David N. Dinkins refused to reappoint Father O’Hare after the board fined the Dinkins campaign $320,000. But Mayor Rudolph Giuliani reappointed him when he took office in 1994.

“It could’ve been a nothing job if it didn’t have a superb leader willing to take on every person in politics,” said Mayor Koch. “He made the job.”

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor worked with Father O’Hare as one of the Campaign Finance Board’s founding appointees.

“Father O’Hare is one of my heroes,” said Sotomayor, a Bronx native who has remained close to Fordham, receiving an honorary degree at 2014’s commencement and attending many University events. “Brilliant, witty, kind, gentle but firm, he lived his life caring and giving to so many. The nation, the city of New York, and the Bronx have lost a great man. I have lost a friend I greatly admired but whose principles continue to guide my life.”

Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg praised Father O’Hare for his integrity.

“Father O’Hare not only began a renaissance at Fordham, he helped clean up corruption in city politics as the founding chair of the Campaign Finance Board,” Bloomberg said. “Appointing him to that post was one of Mayor Koch’s best decisions. He was scrupulously honest, fiercely independent, and never afraid to speak his mind, even when it rubbed elected officials the wrong way. Thanks to him, the city’s public matching funds program, which I was glad to expand, became a national model. In a city of legendary Irish pols, one of the very best never ran for office—but he left a mark on politics like no other.”

Mayor Koch joined several celebrities, religious leaders, and alumni to pay tribute to Father O’Hare when he received the 2003 Fordham Founder’s Award. Present were Cardinal Edward Egan; Cardinal Dulles; best-selling author and Fordham alumna Mary Higgins Clark; CBS newsman and Fordham alumnus Charles Osgood; and Fordham’s incoming 32nd president, Father McShane.

Accepting the award, Father O’Hare—a proud Irishman and humorist—characterized the ceremony.

“It’s something like an Irish wake,” he joked. “Everybody should have one before they die.”

Fordham’s Pastor

Father O’Hare was more than the University president; he was Fordham’s chief pastor and storyteller. During his tenure, he celebrated more than 7,000 Masses, including a Mass of Remembrance and Hope following the attacks on September 11, 2001, which killed three Fordham students and 36 alumni. He performed countless nuptials, burials, and baptisms for members of the Fordham community. He awarded more than 60,000 diplomas and cheered at more than 900 athletics events.

John Feerick, dean emeritus of Fordham Law, recalled Father O’Hare’s pastoral and professional support.

“Father O’Hare meant everything to me when I served as dean of the Law School. He supported me in difficult moments and was always a wise counselor on academic issues and public service undertakings. We owe much to him for the success the school enjoys today,” Feerick said.

“More personally, I will always remember that he was on the altar when my parents died and 10 years later when my brother Donald died. And how can I forget the many times we walked alongside each other in St. Patrick’s Day parades? I watched people wave and call out to him as he waved back with a smile, all while maintaining his quick stride. In everything he was insightful and brought to every occasion a wonderful sense of humor. I will greatly miss him as I had no other friend like him.”

After he stepped down as president in 2003, Father O’Hare served for one year as president of Regis High School, his alma mater. He then returned to the staff of America as associate editor, retiring in 2009. In 2015, with Fordham as a co-sponsor, the magazine established the Joseph A. O’Hare, S.J., Postgraduate Media Fellowship in his honor.

Father O’Hare was the recipient of 11 honorary degrees, including one from Fordham. He served as chairman of both the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities and the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities, a trustee of the Asia Society, and a member of the Charter Revision Commission of the City of New York, among other appointments. For his contributions to the city, he received the 1992 Civil Leadership Award from the Citizens Union of New York. Legendary New York Post columnist Jack Newfield called Father O’Hare “the conscience of campaign finance reform and walking gravitas,” ranking him 44th on a list of “New York’s 50 Most Powerful People” in 1997.

A few years before he left his post as president, Father O’Hare spoke to radio listeners about St. Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuits: “I have always preferred the image of Ignatius the Pilgrim to Ignatius the Soldier,” he said on WFUV’s Fordham Focus on July 30, 2000. “Ignatius the Pilgrim undertook a journey to seek the will of God, searching to discern what the greater glory of God demanded of him and his companions. Such a search, of course, will always challenge the status quo. What has been and what is can never exhaust the vision of what could be and what should be.”

Father O’Hare was preceded in death by his parents; his brother, Gerard O’Hare; and his sister, Marie Scesney. He is survived by nine nieces and nephews and several great-nieces and nephews. A private burial will be held in Jesuit Cemetery, Auriesville, New York. Once the present health crisis has passed, a memorial Mass for Father O’Hare will be celebrated in the University Church. Contributions in his honor may be made to the Joseph A. O’Hare Endowed Scholarship Fund at Fordham. Notes of condolence may be mailed to his niece Claire Scesney Lundahl at 247 East 77 Street, Apt. 5C, New York, NY 10075.

Additional Tributes to Father O’Hare

The Rev. Edward A. “Monk” Molloy, C.S.C., President Emeritus, Notre Dame

Joe O’Hare was a multifaceted leader—as priest, editor, writer, and teacher. Blessed with a great sense of humor, he was a person of vision with a strong international perspective and a deep commitment to Gospel values and human rights. He and I had some wonderful adventures together. He will be deeply missed.

The Rev. John Cecero, S.J., Provincial of the Jesuits’ USA Northeast Province

Father O’Hare was president of Fordham when I began my tenure as an assistant professor of psychology at the University. I had only known him previously through his work as editor in chief of America magazine, and despite his lofty pedigree as a widely respected intellectual, institutional chief executive, and civic leader in New York City campaign reform, he humbly and graciously welcomed me as a new Fordham Jesuit to meet with him to discuss my preliminary research interests and even to solicit some funding to support them! Joe led with insight, wit, and uncompromising loyalty to the Society of Jesus and our mission in higher education, and I will always be grateful for the inspiration that he imparted to me and to so many other Jesuits and lay colleagues at Fordham University.

Paul Guenther, FCRH ’62, Former President of Paine Webber, Former Chairman of the New York Philharmonic, and Former Chair of Fordham’s Board of Trustees

Whenever Joe O’Hare was present, there was an aura which everyone felt. He was an iconic New Yorker, a pastor, and a friend.

Tom Kane, GABELLI ’61, Retired Investment Banker, Former Fordham Board Chair

My long friendship with Father Joe O’Hare began when I joined the Fordham board as a trustee in 1986. We kept a friendly banter going between our two alma maters, Regis and Xavier high schools, throughout our time together.

In 1986, after joining the board, my wife, Judy, and I traveled to Manila for a reception hosted by a fellow trustee, Jose Fernandez, who at the time was minister of finance for the Philippines. The high point of the visit was an audience with the new president, Cory Aquino. Father Joe had been ordained at the Ateneo de Manila and so was friendly with her. (Yes, after the meeting, we did get a Cook’s tour of the shoe collection of Imelda Marcos.)

During the visit, Father O’Hare issued an invitation for President Aquino to visit Fordham while in New York for the opening of the U.N. in September. She graciously accepted.

With the ascension of Mrs. Aquino to the presidency, Philippine nationalism in the world became renowned. On September 22, 1986, Fordham held a special convocation in honor of President Aquino’s visit to Rose Hill. She was presented with an honorary doctorate.

Edwards Parade was packed with Filipinos and Filipino Americans numbering in the thousands and bedecked with yellow ribbons and scarves. The press estimated the crowd at 5,000. When they spotted President Aquino, they went wild with celebration and chanted her name—Cory, Cory! The air was electric.

Gathering himself for a few moments, Father O’Hare then began his remarks in fluent Tagalog, and spoke for over five minutes before switching over to English. To say the crowd went wild with emotion at Joe’s linguistic gesture would be a massive understatement.

Jeffrey Gray, Fordham’s Senior Vice President for Student Affairs

Tall with broad shoulders and a gray mane, regal and striking in appearance, Father O’Hare was a towering figure on campus, in the world of New York City politics, and in the Society of Jesus globally. Anyone who met Joe O’Hare was left with the impression that he could carry the world on his shoulders. A man of unmatched intellect, and personal and professional substance and depth, he was a confident, independent, deep-thinking, and fearless leader who never backed down from a challenge or a challenger. He was a proud New Yorker and man of great loyalty, with a mischievous streak and well developed, wry sense of humor.

Brian Byrne, Former Vice President for Fordham’s Lincoln Center Campus

Father O’Hare grew in his role as University president over his long tenure and in turn grew those who worked closely with him. He had an astonishingly flexible intellect, mastering not only the nuances of the academic world but also the game of politics in his tenure as the first chair of the New York City Campaign Finance Board and president of the Commission of Independent Colleges and Universities.

As a Jesuit priest, however, he always kept his priorities in order. I remember a critical visit to the Albany power brokers with other university presidents which was delayed because Father O’Hare had promised to say Mass in a local parish. He was a student of the ironic in life, frequently noting his tendency to tell the world how it should behave yet remaining firm in his commitment to advance fairness and civility.

Bruno M. Santonocito, Former Fordham Vice President for Development and University Relations

Father O’Hare’s 19-year presidency set in motion some of the foundational steps that have led to the extraordinary success Fordham University enjoys today. He revitalized and reengaged the alumni community’s commitment to Fordham. He spent numerous hours with alumni either individually or at small gatherings or when giving his state of the University message to the various alumni chapters around the country and abroad. Through these activities, Father was able to recruit an active and involved Board of Trustees who were critical to the successful completion of the Fordham University Campaign in our sesquicentennial year.

He loved rubbing shoulders with our graduates who talked about him affectionately as “the priest from central casting.” And when he was with our alumni what was always on display was his charm and graciousness, his warmth, quick wit, sense of humor and mastery of the good joke and the good story. Father had style, delivery, and timing!

Finally, he had loyalty to and affection for all his vice presidents. In spite of that, he could not resist telling alumni that like a herd of elephants or a gaggle of geese, he had a “confusion” of vice presidents.

Simply put, Father O’Hare was the right man at the right time for Fordham and I feel privileged to have shared a good part of his tenure at his side.

Dorothy Marinucci, Associate Vice President for Presidential Operations

There was a brilliant Jesuit, Father John Donohue, S.J., who worked for many years as an associate editor at America magazine. He was a good friend of Father O’Hare. Whenever you visited Father Donohue as you were leaving he would say, “safe home.” I know Father O’Hare particularly liked this phrase. I know no more fitting tribute than to quote Father Donohue and say, “Safe home, JO’H.”

Nicole A. Gordon, Faculty Director of the CUNY Baruch College Executive M.P.A. program and Distinguished Lecturer of Public Affairs; Founding Executive Director of New York City’s Campaign Finance Board

Father O’Hare was the inspired choice of Mayor Ed Koch to be the founding chair of the pioneer New York City Campaign Finance Board in 1988.

The public record truly speaks for itself, including the many times when our board chair had to face off against powerful interests. Each time, Father O’Hare challenged efforts to intimidate and undermine the board, and in each instance, he prevailed. These occasions included attempts by elected officials to replace him as chair, to move the board’s offices to uninhabitable quarters, to stop valid matching funds checks to candidates, and to stack the board with a new member in the midst of public hearings on apparent (and, later, confirmed) substantial violations of the campaign finance law.

One wonderful exchange–among many on TV–was aired when a candidate’s spokesperson described how he had hired the most prominent law firm in the City to fight the CFB. Father O’Hare responded, “So, sue me!”.

Working closely with him, as I was privileged to do for some 15 years, was an experience next to none. As a leader of troops, Father O’Hare’s sharp intelligence, political acumen, crushing wit, unquestionable loyalty, and (literally) priestly status gave us daily lessons on how to operate in public and in private, especially when the job is to be independent and fair in a volatile arena and without natural allies.

Would that we had him with us now.

]]>

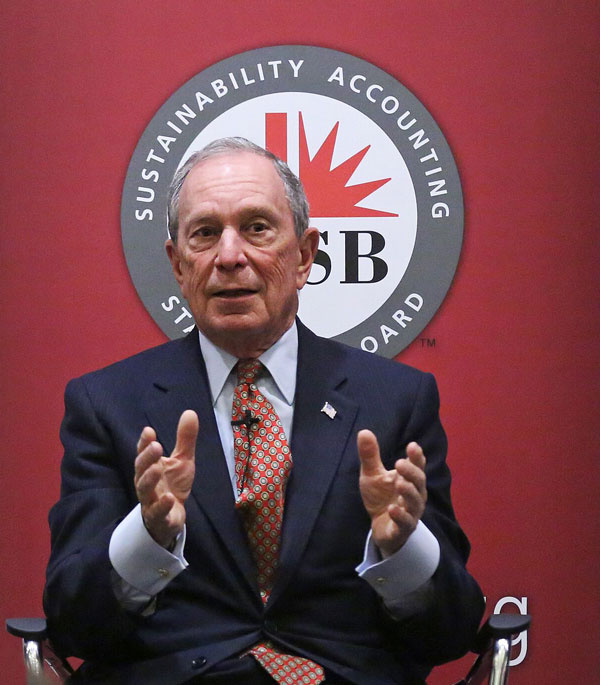

At a keynote discussion on Nov. 30 at the Lincoln Center campus, the media mogul argued that social, environmental, and governance issues like population growth, climate change, and technological advances can influence stock price performance and a corporation’s value in the long run.

“[Sustainability] is in the world’s interest and the companies’ interests,” he said. Bloomberg, who has been a global leader on climate action for the business community and local governments, pointed out that long-term oriented investors tend to align with companies that are the “most resilient to catastrophe and efficiently-run.”

The panel discussion, moderated by Mary Schapiro, former chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), also featured William McNabb, chairman and CEO of the mutual fund giant Vanguard. It was part of the 2017 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) Symposium, which was hosted by the Center for Professional Accounting Practices of the Gabelli School of Business. Focusing on market forces at work, the daylong event offered industry observations on sustainability disclosure, market standards, and investor demands from leaders of top companies such as JetBlue, UPS, Goldman Sachs, and Bank of America.

As head of a company that represents more than 20 million investors worldwide, McNabb penned an open letter this past August to directors of global public companies in Vanguard’s portfolio, in which he said that companies must stay abreast of risks and opportunities because they help boost shareholder value.

“If one company is doing a really good job of disclosing risks—whatever the risks may be—it allows you as an investor to have a much better perspective on what that company might be worth going forward,” he said. “I think as an investor that’s what you want to be doing.”

But investors aren’t the only ones paying attention. Bloomberg, who serves as the U.N’s Special Envoy for Cities and Climate Change as well as chairman of the SASB Foundation board in addition to a host of other environmental organizations, said more people are gravitating toward companies that are making sustainability a priority—from prospective employees to new customers.

“In this day and age, when you’re recruiting young people out of college, they are interviewing you,” he said. “And they’ll say, for example, what are you doing in the climate area? So, it’s a real competitive thing to do well, and we keep trying to point that out to companies.”

To help companies improve sustainability disclosures in SEC filings, SASB has developed industry-specific sustainability accounting standards. According to Bloomberg and McNabb, this creates transparency and gives companies a competitive edge.

“We’ve always had a saying at Bloomberg that ‘if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it,’” Bloomberg said. “So, if investors want to look at what companies are doing, we make it easier for them to do it.”

The finance giants project that the marketplace, and not regulators, will be the most influential in bringing sustainability standards closer to the forefront. Bloomberg said that this is because, “it’s almost impossible to write one law that covers everything.”

For McNabb and Vanguard, the goal is for the market to coalesce around a framework that encourages companies to provide consistent and comparable disclosure.

“It’s pretty hard to argue that being well-governed is going to hurt your value,” he said.

]]> Few would dispute that an educated public makes for a competitive and industrious nation. But in any given year, at least 50,000 low- and moderate-income students at the top of their class do not enroll in one of the nation’s top-performing institutions.

Few would dispute that an educated public makes for a competitive and industrious nation. But in any given year, at least 50,000 low- and moderate-income students at the top of their class do not enroll in one of the nation’s top-performing institutions.

Now Fordham is joining a coalition of prestigious universities nationwide with a stated goal of educating, by 2025, some 50,000 additional high-achieving, lower-income students at the 270 colleges and universities with the highest graduation rates.

Known as the American Talent Initiative (ATI), the coalition was formed last year with the support of Bloomberg Philanthropies, to enhance coordination among top colleges in identifying and recruiting these lower-income students.

Of the 270 colleges with highest graduation rates, 68 have committed to the program, with Fordham joining 38 new members this year, along with Columbia and New York Universities.

“Too many students from low-income families are missing out on opportunities to attend top colleges because they think those colleges aren’t affordable–when most often, they are,” former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg said in a statement.

“Too many students from low-income families are missing out on opportunities to attend top colleges because they think those colleges aren’t affordable–when most often, they are,” former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg said in a statement.

According to recent studies, at least 12,500 high school seniors per year have SAT scores in the top 10 percent, with 3.7 grade point averages or higher, but still do not attend top tier colleges because they lack information about their options, confusion about costs, and inadequate financial aid.

“We’re aiming to help all ATI members enhance their own efforts to recruit, enroll, and support lower-income students, learn from each other, and contribute to research that will help other top colleges and universities expand opportunity,” said Martin Kurzweil, director of the Educational Transformation Program at Ithaka S+R, which is co-coordinating the program with the Aspen Institute’s College Excellence Program.

The co-coordinators will help member universities share institutional data to be published annually and track members’ progress toward meeting the 2025 goal. Colleges and universities participating also use their shared data toward best practices that ensure those students graduate.

]]>The session will also feature Seth Pinsky, former president of the NYC Economic Development Corporation. Richard Schwartz, former editorial page editor and columnist at NY Daily News, will moderate the discussion.

The event will mark the fourth in a series that began in November 2014 with a Fordham-sponsored conference on New York City’s Bloomberg era. The morning will include the special interview session and a complimentary breakfast.

The event is free and open to the public. RSVP by email or call (718) 817-0180.

]]>He stressed the vigilance needed to prevent future attacks, calling cyberterrorism something “we have to be very much concerned about,” and also touched on some of the controversial moments of his 12 years as commissioner under Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Kelly was interviewed by William F. Baker, PhD—Journalist in Residence and Claudio Aquaviva Chair at Fordham—about many topics featured in his just-published memoir, Vigilance: My Life Serving America and Protecting its Empire City (Hachette Books, 2015). The interview was part of the University’s Oral Archive on Governance in New York City: The Bloomberg Years.

Kelly served as commissioner from 1992 to 1994 and again from 2002 to 2013, the longest-ever tenure in the job. Discussing the 16 terrorist attacks thwarted on his watch, he said some were stopped by “sheer luck,” like the attempted Times Square bombing in 2010 that fizzled because the would-be bomber, Faisal Shahzad, bought weaker components than he needed.

Citizens still need to be vigilant to help stop attacks, though.

“The further we get away from a terrorist event, the less concerned people are,” he said.

In response to a question about the department’s so-called “stop and frisk” policy, he defended it by noting it’s backed up by common law and the U.S. Supreme Court. Officers in “every state in the union” are authorized to intervene when they see something they reasonably believe indicates a possible crime, he said.

“It is a valuable tool that police officers need to hold onto,” he said, adding that he knows it’s not a panacea or “cure-all.”

Asked about the drop in crime during his tenure and the recent uptick in shootings and homicides, Kelly said, “In my judgment, it’s up because police are hesitating.” He pointed to new oversight measures like an outside monitor mandated by a federal court ruling, which stemmed from a lawsuit alleging racial profiling by police. That and other measures send police “a message to do less,” he said.

He noted the department is “by far the most diverse” in America, with officers born in 106 countries.

When an audience member asked about how to prevent shootings in the city, Kelly described one initiative from 2012 and 2013 that led to the city’s lowest annual number of shootings, murders, and shootings by police ever recorded.

After finding that 30 percent of shootings and murders were originating with loosely organized “crews,” or gangs, the department expanded its anti-gang unit and tracked the signals that crew members were sending on social media, among other measures, leading to 25 major investigations and 450 indictments.

“That proactive approach to these types of gangs, or crews, worked for us,” he said.

He said he supports body cameras for police. In addition to deterring misconduct, he said, “they will show the great work that police do, really throughout the country—heroic work, beneficial work, good work—but also show events that happen, ideally, from start to the end, as opposed to seeing a YouTube video that starts in the middle of something.”

]]>

For almost every New Yorker, 9/11 became a defining moment that changed the course of the city as a whole and individual lives as well, including that of former Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Participating in an ongoing video series focusing on the former mayor’s legacy, William Cunningham, his former communications director, said that the tragedy added an urgency to win the 2001 campaign.

Cunningham was joined by Haeda Mihaltses, FCRH ’86, GSAS ’94, former director of intergovernmental affairs. The May 28 conversation took place at the Lincoln Center campus. William Baker, PhD, the Claudio Acquaviva Chair in the Graduate School of Education, moderated.

Cunningham said that Bloomberg, a licensed pilot, knew instantly that the plane crashes were an attack even as others debated radar malfunction.

“He immediately cut to the big problem,” said Cunningham. “That’s his nature: What’s the problem and what do we do about it?”

For the then-candidate, that meant winning the election in order to help the city rebuild. But first he had to win. As 9/11 occurred on primary day, voting and campaigning were suspended for another two weeks while the city grieved.

Bloomberg re-approached the campaign with sensitivity, said Cunningham. His first speech after the attacks was held in Queens, with midtown skyscrapers serving as backdrop so as to not appear to be capitalizing on the void left in the downtown skyline.

Before the attacks, political veteran Mark Green was the front-runner. But after the attacks, the Bloomberg campaign focused voter attention on their candidate’s business expertise.

“Green knew the politics, but now the question was who can manage a multi-billion dollar enterprise that theoretically could collapse around you,” said Cunningham. “New York needed a mayor who could talk to the people that make those decisions.”

Cunningham reminded the audience that with the financial district still smoldering, leaders in Washington were beginning to argue that the financial sector shouldn’t be so centralized in one place and on the same grid.

“Chicago and New Jersey were making a bid for finance,” he said.

Former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s endorsement was key to the win. The endorsement was quietly cultivated out of the spotlight, said Cunningham. The campaign allowed Giuliani to pick the endorsement date and time, which happened to be on a Saturday at 4 p.m.—not exactly the ideal time for Sunday newspaper deadlines. But behind the scenes, the campaign already had commercials featuring Giuliani’s endorsement shot and they were scheduled for the Sunday morning talk shows.

The strategy worked, he said. The unlikely billionaire candidate became the 108th mayor of New York City.

On arriving at City Hall, the mayor asked his staff to call him Mike, a request that they politely denied, said Mihaltses. It would be the first of many disagreements that the mayor would have—indeed encourage—from his deputies.

“We told him, ‘With all due respect you are the mayor of the City of New York,” said Mihaltses, who was part of the team that gave Bloomberg his crash course on city government.

Mihaltses described an engaged management style that was kind, “sometimes to a fault.”

“He wasn’t a micromanager,” she said. “He let managers do their jobs but he watched and made sure that he was part of the decision making.”

She described a challenging first year that included an 18.5 percent tax hike, followed by across-the-board budget cuts. She said an economic downturn coupled with the 9/11 attacks meant the city needed the revenue. The tax hikes were quickly followed by the smoking ban and mayoral control of the school system.

“That’s a pretty good first year,” said Cunningham.

Mihaltses and Cunningham said that almost all of the gains, whether they were accomplished in Albany or in City Hall, could be attributed to tight team coordination and the mayor’s willingness to meet repeatedly one-on-one with state legislators and city council members.

“He went to Albany again and again, he made the case with editorial boards and columnists,” said Cunningham. “He was very good about getting back to the legislators.”

The two discussed rezoning the city, overturning term limits for the mayor’s third term, and public safety. But ultimately, while the timing of the video series is good for fresh memories, they said that many of the mayor’s real accomplishments may not be realized for years to come. Mihaltses noted that the rezoned development at Hudson Yards and Coney Island is far from done. And Cunningham said that the data on the effects of the smoking ban is just beginning to accumulate.

“It wasn’t until the Giuliani administration that we realized the [value of the]housing plan that Ed Koch had accomplished,” he said. “There are many things we wont know until 20 years from now. And the longer view will be better.”

The discussion was part of the University’s Oral Archive on Governance in New York City: The Bloomberg Years.

]]>

Those and other questions were put to Howard Wolfson, Bloomberg’s former deputy mayor for government affairs and communications, on March 26 in an interview launching Fordham’s Oral Archive on Governance in New York City: The Bloomberg Years.

Wolfson was interviewed by Costas Panagopoulos, PhD, professor of political science and director of Fordham’s Center for Electoral Politics and Democracy. Wolfson offered an insider’s glimpse of the former mayor as person, policymaker, and visionary.

He said that, contrary to Bloomberg’s media image as billionaire technocrat, the businessman-turned-mayor was adept at wearing a politician’s hat and enjoyed mingling with the public during campaigns and other public events.

“People forget that the skills he brought to Bloomberg Industries were the skills of a salesman,” said Wolfson, who still works with Bloomberg on his philanthropic endeavors. “He knows how to sell a vision, a concept,” something he has done since he was designing and creating financial information terminals as an entrepreneur.

Nevertheless, Wolfson said that Bloomberg’s foremost talent—in fact, “his calling”—is in bullpen-style management and in the running of a complex organization. It was that aspect of being mayor that Bloomberg enjoyed the most.

Another asset was Bloomberg’s lack of political experience prior to his election—a plus because he didn’t know what “couldn’t be done.”

“He hadn’t spent 20 years in politics learning the ‘rules of the road,’ which tend to narrow people’s sense of what is possible,” said Wolfson. “It was easier for him to see his way toward ‘yes.’”

That Bloomberg vision, coupled with his willingness to push unpopular public policies, resulted in political wins, such as his citywide smoking ban, but also failures, such as congestion pricing and a ban on large sugary drinks.

Even then, said Wolfson, Bloomberg saw success in his attempt to pass regulations on sugar intake, because it inspired a closer look at the issue.

“What we tried to do with sugary drinks in New York changed the debate nationally,” he said. “Sometimes what one person might call a failure he would consider a success: Okay, the court struck it down but we changed the conversation.”

As a manager, Bloomberg showed fierce loyalty to staff, said Wolfson. Under his tenure, it was frowned upon to be unsupportive of a colleague; Bloomberg once told him that “the day that newspapers are going after you, that’s the day I walk around with my arm around you.” When questioned by news media, Bloomberg has refused to criticize the current mayor, Bill de Blasio–which Wolfson sayshe does out of respect for the office in which they both have served.

Those areas in which the Bloomberg administration faced public criticism— stop-and-frisk, low-income housing, income inequality, the disastrous school chancellor appointment of Cathie Black—were also raised.

Regarding Black, Wolfson said that Bloomberg would never use the word “sorry” with regard to the appointment, but acknowledges that she was not the right fit. As to poverty and income inequality, Wolfson said the mayor would not view himself as the “great leveler,” rather he sought to create opportunities for poor and middle-class New Yorkers, who he said fared better than the poor in other cities during economic downturns. In fact, he welcomed the rich as a means of strengthening the city’s tax base in order to redistribute monies to those in need.

Bloomberg took office in 2002, immediately following the single most tragic event in the history of the city. Wolfson speculated that he will be remembered as “the guy who came in after 9/11” and created the memorial museum to honor those who died. The larger legacy, however, will be the mayor’s vision for rebuilding an economically collapsed, spiritually broken city.

“At a time of enormous difficulty in the city’s history, he was able to assume leadership [and]give people confidence in New York,” he said. “He believed in the promise and the future of New York. [Even today] he sees it as a gateway to opportunity.”

— Janet Sassi

]]>An overarching theme, members of his administration suggested on Nov. 27, will be helping New Yorkers live longer, more enjoyable lives.

“He thinks that if we have extended the lives of New Yorkers, giving them an opportunity for a long and healthy life, then he’s done a good job as mayor,” said the Hon. Thomas Farley, New York City commissioner of health and mental health.

Farley was one of five experts from the fields of law, public health, and policy to weigh in on the mayor’s legacy at “The Bloomberg Administration’s Legal Legacy,” a two-night symposium co-sponsored by Fordham Law School and the New York City Bar Association.

Panels on safety and public health were part of the symposium, the inaugural event of the new Fordham Urban Law Center.

Farley discussed the range of high-profile public health initiatives the administration has implemented, including bans on smoking and trans fats, calorie labeling requirements, and the recent prohibition on the sale of large sugary drinks.

Referencing changes in health and social norms particularly with regard to smoking, Farley said the policies have been both socially and economically beneficial for the city.

“This is the perfect example of how policy can be effective, but also cost effective,” he said.

But Peter Zimroth, partner at Arnold & Porter LLP, who represented the restaurant industry in its battle against New York City’s calorie count requirement, challenged Farley on the efficacy of the Bloomberg health initiatives related to obesity.

“There’s a serious cost to be paid with initiatives like calorie labeling if, in the long run, they don’t work. There’s a limited amount of capital that government has to engage in coercive measures,” Zimroth said.

While the use of policy to affect public health is nothing new, Farley said that the mayor has been particularly innovative in using it to address obesity.

“The biggest legacy of the Bloomberg administration is the use of laws and policies to promote health in a modern era when …our biggest killers are things that can be seen as specific behavioral choices,” Farley said.

Nestor Davidson, professor of law and director of the newly launched center at Fordham Law, said the school created it to coalesce the already strong urban law resources in place at Fordham.

“It is our hope that the center will help foster conversation about the role of law across a range of policy questions that cities are grappling with,” Davidson said.

The symposium continues on Dec. 4 with panels focusing on education and land use and sustainability.

— Jennifer Spencer

An overarching theme, members of his administration suggested on Nov. 27, will be helping New Yorkers live longer, more enjoyable lives.

“He thinks that if we have extended the lives of New Yorkers, giving them an opportunity for a long and healthy life, then he’s done a good job as mayor,” said the Hon. Thomas Farley, New York City commissioner of health and mental health.

Farley was one of five experts from the fields of law, public health, and policy to weigh in on the mayor’s legacy at “The Bloomberg Administration’s Legal Legacy,” a two-night symposium co-sponsored by Fordham Law School and the New York City Bar Association. Panels on safety and public health were part of the symposium, the inaugural event of the new Fordham Urban Law Center. (story continued below)

Farley discussed the range of high-profile public health initiatives the administration has implemented, including bans on smoking and trans fats, calorie labeling requirements, and the recent prohibition on the sale of large sugary drinks. Referencing changes in health and social norms particularly with regard to smoking, Farley said the policies have been both socially and economically beneficial for the city.

“This is the perfect example of how policy can be effective, but also cost effective,” he said.

But Peter Zimroth, partner at Arnold & Porter LLP, who represented the restaurant industry in its battle against New York City’s calorie count requirement, challenged Farley on the efficacy of the Bloomberg health initiatives related to obesity.

“There’s a serious cost to be paid with initiatives like calorie labeling if, in the long run, they don’t work. There’s a limited amount of capital that government has to engage in coercive measures,” Zimroth said.

While the use of policy to affect public health is nothing new, Farley said that the mayor has been particularly innovative in using it to address obesity.

“The biggest legacy of the Bloomberg administration is the use of laws and policies to promote health in a modern era when … our biggest killers are things that can be seen as specific behavioral choices,” Farley said.

Nestor Davidson, professor of law and director of the newly launched center at

Fordham Law, said the school created it to coalesce the already strong urban law

resources in place at Fordham.

“It is our hope that the center will help foster conversation about the role of law across a range of policy questions that cities are grappling with,” Davidson said.

The symposium continues on Dec. 4 with panels focusing on education and land use and sustainability.

– Jennifer Spencer

]]>