Hoffman was widely respected at Fordham for her interdisciplinary expertise and collaborative spirit.

Elizabeth Stone, Ph.D., a professor of English, said that despite their different fields of study, they grew to be fast friends.

“I always knew we spoke the same language. Decade after decade, our conversations about one another’s work were immensely gratifying,” she said.

Magda Teter, Ph.D., the Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies at Fordham, called Hoffman “a beloved member of Fordham’s Jewish Studies community” and said her work was marked by “great erudition and disciplinary depth.”

“In her 1991 work on the Hebrew writer and Nobel Prize laureate S.Y. Agnon, she deployed a wide range of theoretical tools, ranging from psychoanalysis to feminist theory,” Teter said.

“She placed Agnon in conversation with other writers, such as James Joyce, Kafka, and Thomas Mann. … She was able to handle, with equal care and knowledge, traditional Jewish text and modern philosophy.

Hoffman was born on June 19, 1946, in New York City and grew up, along with her younger brother, David, in Brooklyn. She earned a bachelor’s in English and Comparative Literature from Cornell University and a master’s and Ph.D. in English and Comparative Literature from Columbia University. She was a special member of Columbia’s Association for Psychoanalytic Medicine.

She joined Fordham in 1979 and taught courses in Israeli literature and film as part of Fordham’s Middle East Studies program. In 1992, she created the annual Nostra Aetate Dialogue series, which brought together Jewish and Christian scholars to address questions pertinent to Jewish-Catholic reconciliation. In 2002, she also helped found Fordham’s Jewish Texts Reading Group, which still meets today.

Hoffman was an accomplished painter. In 2015, she opened up about her creative process in a lecture at the Walsh Library. Last November, her art was displayed at Fordham’s Butler Gallery.

Hoffman was known at Fordham as a skilled instructor and generous mentor. Fordham professor of biology Jason Morris, Ph.D., said she taught him how to be a better teacher.

“I learned so much from teaching with Anne. She appreciated nuance: she had a deep mistrust of facile answers and sharply drawn lines,” he wrote in an email.

“Her integrity and her empathy (and despite what she said, her expertise) came across in everything she said and did.”

In 2003, she was honored with Fordham’s Outstanding Teaching in the Humanities Award, and in 2019, she was recognized for 40 years of service at Fordham. She retired in 2023 and was named professor emerita.

Nikolas Oktaba, a 2015 graduate, took a class with Hoffman, and like many students, he kept in touch with her after graduation. He called her a “fount of tranquil wisdom.”

“Not only did she put her students first, but she did so in a way that allowed them to see the perseverance, resilience, and strength that they already held within them,” he said.

At the time of her death, in addition to her painting, she was teaching writing skills at the Fortune Society, teaching Freud at the New York Psychoanalytic Institute, and conducting friendship-focused writing groups at the Asian University for Women (AUW) in Bangladesh via Zoom.

Leon Hoffman, M.D., Anne’s husband of 57 years, said that he would forever hold onto a memory of the two of them walking together when she was an undergraduate and he was attending medical school.

“We had one of those adolescent discussions of the time: would we marry someone who was not Jewish? I responded very quickly, ‘That is an academic discussion because I am going to marry you.’ She was shocked, but the rest is history,” he said.

“We were not tied at the hip, but we were tied with our brains and our love.”

In an interview last year, Hoffman recalled what her late father-in-law said when she received her first summer grant to travel to Israel to explore Agnon’s archive.

“He observed that it truly is the ‘goldeneh medineh’ (a Yiddish term referring to the U.S. as the golden land) when a Catholic university gives a Jewish girl money to go to Israel to work on Agnon,” she said.

“Even more than the material support, his remark captures something of the openness and generosity that have been my experience of this university, my academic home for over 40 years.”

Hoffman is survived by her husband, Leon Hoffman, M.D.; her children, Miriam Hoffman, M.D. (Steven Kleiner, M.D.) and Liora Hoffman, Ph.D. (Rob Yalen); her brother, David Golomb; her niece, Danielle Golomb, M.D.; her nephew, Jesse Golomb; and her grandchildren Shoshana, Elisheva, and Hillel Hoffman Kleiner and Greta and Max Yalen.

A memorial service open to the University community will be announced at a later date.

]]>]]>The Fordham University historian Magda Teter follows the spread of these deadly allegations, which exploded after the successful Trent prosecution, in her 2020 book, Blood Libel: On the Trail of an Antisemitic Myth. The work’s accompanying maps trace more than 100 such accusations, delineating them by criteria such as whether there were “legal proceedings” (73 yes, 30 no) or “Jews killed” (31 yes, 55 no, 13 unknown).

For Sophia Maier, a senior at Fordham College at Rose Hill, interest in Bronx Jewish history was sparked when she interviewed her grandparents about their upbringing for a Bronx history course at Fordham.

“I said, ‘all right, well this is really important,’” she said. “So I did my thesis on doing oral history interviews with folks who grew up in the Bronx and left during the period of white flight in the 60s and 70s and into the 80s.”

She added that her research, which included interviews with more than 40 community member so far, focused mainly “on the 40s, 50s, and into the early 60s—a lot of those folks are people whose grandparents immigrated to this country, typically from Eastern Europe.”

“Since they came into this country, there has been this sort of upward movement—both geographically and on a class basis, starting out on the Lower East Side, or Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in this kind of crowded tenement living, [and then]folks moved up to the South Bronx, or then further up into the Northwest Bronx.”

Maier and Reyna Stovall, a sophomore at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, shared their research on March 1 at “Jews in the Bronx: Archival and Oral Histories,” an event hosted by Center for Jewish Studies. They were joined by Daniel Soyer, Ph.D., professor of history; Ayala Fader, professor of anthropology; and Ayelet Brinn, Ph.D., the Philip D. Feltman assistant professor of modern Jewish history at the University of Hartford who did postdoctoral research at Fordham.

The students’ work is at the heart of a new initiative of the Center—the Bronx Jewish History Project, which was publicly launched at the event. Maier’s interviews, paired with Stovall’s archival research, are the basis for the project, Sarit Kattan Gribetz, Ph.D., associate professor in the theology department, said. It was also partially inspired by the Bronx African American History Project, which was founded by Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of African and African American studies.

Magda Teter, Shvidler Chair of Judaic Studies and co-director of the Center for Jewish Studies, helped introduce and combine the students’ work into a larger project that will live beyond their time at Fordham, Gribetz said.

“Through our new initiatives at the Center for Jewish Studies, we’re collaborating across generations and fields to collect, preserve, share, and learn from these stories,” Gribetz said.

Piecing Together History

Stovall came to Fordham from San Antonio, Texas, and didn’t have any connection to the Bronx. Working for the Holocaust Museum in Texas piqued her interest in Jewish Studies though, so she minored in it at Fordham, and met Teter.

“I met Dr. Teter, who said, “Oh, we just got these new interesting documents from the Jewish Bronx, and I thought, ‘The Jewish Bronx? I thought the Jews lived in Brooklyn,’” Stovall, who is Jewish, said with a laugh. “I wasn’t aware of the significance of the Bronx to Jewish history.”

She began interning with the center last semester and began “deep diving into all of these archives that we started acquiring.” In the spring of 2020, the center hosted a virtual event called “Remnants: Photographs of the Jewish Bronx.”

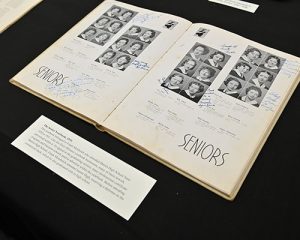

Ellen Meshnick Immerman, who grew up in New York, attended, and was so inspired by the event that she donated material, including everything from yearbooks to bar mitzvah invitations from her parents, Frank and Martha Meshnick, who had grown up in the Bronx.

“Looking at them was absolutely fascinating to me—getting to know people’s stories through the little bits and pieces of their lives,” Stovall said.

The Meshnick’s documents “really opened my eyes to how special the Bronx is,” she said.

Stovall also spoke with Meshnick Immerman, and the conversation elevated the work to a new level, she said.

“I had this vision of what their life was like in my head, but getting to talk to her, I got to know more the feelings that were associated with it—how her mother put so much pride in her appearance, how they went to these stores to prepare for these certain things for their Shabbat days, just things like that that showed me the dimensions of history.”

Capturing Untold Stories

Maier’s project started with interviews with her grandparents, and is rooted in oral histories. She’s conducted more than 40 interviews so far, with “more coming everyday,” including one scheduled in a few days with a Bronx resident who survived the Holocaust.

She found that Jewish people, particularly those in the South Bronx through the 40s, 50s, and 60s, lived in “really diverse neighborhoods and environments” where they felt “secure” and like they were a part of a larger community.

“People were like, ‘Oh, I never locked my door,’ or ‘My Italian neighbor across the street, she’d always give me cookies when I came home,’—things like that, that kind of captures the sentiments of how people were feeling,” she said.

Residents described how schools were integrated, although there were tactics employed to keep many of the white students in classrooms separate from the Black students. But many said their diverse, public education was at the heart of the upward mobility they were able to achieve.

“For a lot of the people that I spoke to, their parents were kind of manual laborers, truck drivers, small business owners, factory workers. But because of the great public education that they got and continued for college education, a lot of them were teachers and doctors of various kinds.”

Many Jewish people left the Bronx, Maier said, as a part of their “striving toward this solid middle class standard of life,” which included wanting more space for their families and being able to afford the suburbs. But interviewees also told her their families left because “the Bronx was changing.’ At that time, many Black and Hispanic residents were moving into the Bronx, and many Jews people moved out.

“Leaving the Bronx for a lot of Jews, meant leaving this distinctly Jewish place—you didn’t have to be a religious Jew to be a Jew in the Bronx,” she said.

Tying the Stories to the Artifacts

Stovall said that she believes this marriage of archival material with oral histories is what makes the Bronx Jewish History Project so unique.

“I get to see both sides of history—the emotions and feelings that are associated with the Bronx, but also the archival materials,” Stovall said, adding that the project will carry a record of their history forward.

Learn more about the Bronx Jewish History project and other initiatives taking place at the Center for Jewish Studies.

]]>Today, the program, which is jointly run by Fordham, the American Academy for Jewish Research, and the New York Public Library, continues to support these scholars, many of whom had to flee their homeland.

When the program was conceived, Fordham offered a year-long fellowship to a student pursuing master’s level studies in the area of Jewish and Slavic studies. The others, a mix of Ph.D. students and scholars working in the same area, were provided stipends, access to electronic resources at Fordham and the library, and invitations to five remote workshops.

Magda Teter, Fordham’s Shvider Chair in Judaic Studies and an administrator of the program, said the program will help scholars document this period in history. She said a source of inspiration for the project was the work of Samuel Kassow, who wrote about the efforts to document the experience of living in the Warsaw ghetto during the Holocaust in his 2007 book Who Will Write our History? (Indiana University Press, 2007).

“I think it is important for the moment to gather, to collect, to preserve, to remember,” she said.

“It is our duty to help these scholars in any way we can. Even small stipends mean a lot to them when their institutions have been bombed or are inaccessible.”

Working Even When the Lights Go Out

When Tetyana Batanova delivered the lecture “Yiddish Sources and Resources: My Personal Path to Jewish and Yiddish Studies” virtually from her apartment in Kyiv in the lecture series “Scholars at War” on April 8, it was a welcome splinter of normalcy. Russian armed forces, which had occupied her Kyiv suburb of Bucha in the opening month of the war, had only retreated from the area a week earlier.

Batanova, the acting head of the Judaica Department at the V. Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine, had been conducting research for her dissertation about the five Jewish political parties that participated in Ukraine’s national government in 1917-1918. At the time, Yiddish was one of four officially recognized languages in the country. Today only Ukrainian is officially recognized by the government.

With her country facing an existential crisis, Batanova said she had serious doubts about the importance of her research. The fellowship has helped restore her faith.

“Seven months later, I’m more confident in what we do, and that we should continue,” she said.

“But in April, it was not that obvious for me at all. When I was invited to give my lecture, it was good that it was in April, because in March I was not able to speak at all.”

Historical research is only as good as the original sources one can acquire, and having worked at the New York Public Library in 2006, Batanova knew what kinds of archival documents and journal articles she’d need. As a result of the fellowship program workshops, she was able to access new books from Fordham University Library online resources providing the context for her research, such as Stephen Velychenko’s book Life and Death in Revolutionary Ukraine : Living Conditions, Violence, and Demographic Catastrophe, 1917-1923 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021).

Her research focuses a great deal on Yiddish, a language intrinsically tied to the Holocaust and its victims. It was also the primary language of the 30,000 to 70,000 killed in anti-Jewish pogroms that swept Ukraine in 1919.

Although it is still spoken in pockets around the world, its importance is not widely known, making it an ideal path for the average citizen to learn about Ukrainian history, Batanova said.

“The story of Yiddish is quite similar to the story of Ukraine in the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.”

Fleeing War for NYC

Andrii Pykalo was just beginning his graduate studies when the war began. He attended V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, in Kharkiv, the country’s second-largest city just 25 miles from the Russian border. Feb. 24, the day that Russia attacked, will forever be cemented in his mind.

“I will never forget the sky over my neighborhood. It was yellow, because of all the Russian rockets,” he said.

“It was very, very noisy, and I remember the panic. It was a horrible surprise for all.”

Continued study in Kharkiv was never an option; for starters, the university library was hit by a Russian missile. Pykalo said he tried to help save some of the books from the collapsed structure.

He had to jump through numerous bureaucratic hoops to leave, but he was granted permission in May, and he arrived in New York City to attend Fordham on Aug. 23. He has been living in an off-campus apartment in Harlem and attending classes, such as one on antisemitism with Teter and another one about advanced research methods by history professor Grace Chen, Ph.D.

For his research project, “Soviet Jews and the History and Memory of the Holocaust in Ukraine,” he’s been able to use his time in New York to locate documents that show how Americans viewed Jews in the Soviet Union at that time.

Apps such as Telegram and WhatsApp have made it possible for Pykalo to stay in touch with his friends and family, and he’s also connected with the Ukrainian diaspora in the East Village. But the decision to leave Ukraine was a fraught one.

“I understood that I should have been in Ukraine defending my country. I should be with my family, I should be with my friends,” he said.

“I was really afraid for my family, but they all told me that I must go because it’s my profession. This is my task.”

Seeking Safety in Michigan

Yurii Kaparulin, Ph.D., an associate professor of history and legal scholar at Kherson State University in southern Ukraine, found himself on the wrong side of the border when war broke out. While his wife and son were home in the city of Kherson, he was in Bucharest, Romania. His family spent a month in Kherson while it was occupied by Russian forces before they were able to evacuate and reunite. In August, they moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where Kaparulin received a separate, “scholars at risk” fellowship from the University of Michigan’s Weiser Center for Europe and Eurasia.

For Kaparulin, the Fordham fellowship, which he was offered after moving to Ann Arbor, has been invaluable for the completion of his book, “Between Soviet Modernization and the Holocaust: Jewish Agrarian Settlements in the Southern Ukraine (1924-1948),” which he began seven years ago.

The war forced him to leave behind some of his own research, but more importantly, he lost access to his own university’s archives.

“Before Russian troops left Kherson, they looted the biggest part of the Kherson State archive. So I needed to figure out where I would look for sources and get some of the newest articles and books,” he said.

Through the Fordham fellowship, he’s been able to access resources such as the article Farming the red land: Jewish agricultural colonization and local Soviet power, 1924-1941 Jonathan L. Dekel-Chen, (Yale University Press, 2015), and “Men inspecting foals at an artel supported by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Kherson, Ukraine” a black and white photo from 1924.

His project addresses mass violence and wartime collaborators from the past–both of which have ties to the present. One of the reasons why Russian President Vladimir Putin has smeared Ukrainians as Nazis, he said, is because there were, in fact, Ukraine citizens who collaborated with the Nazi regime during World War II.

However, Russian propaganda effectively ignores the contribution of millions of Ukrainians to the victory over Nazism, he said. That is, when it comes to examples of collaborationism, the Ukrainian origin of the accused is emphasized, he said, and when it comes to heroism and victory, “Soviet heroes” are mentioned without ethnic context.

The phenomenon of collaborationism has also been observed during Russia’s current war against Ukraine. For example, during the occupation of Kherson from March to November 2022, some residents cooperated with the Russian occupiers.

“Their motives are currently being established by law enforcement agencies. However, in general, we see that the majority of the city’s residents have maintained the Ukrainian position despite various risks, including to their lives,” he said.

Providing Tools for Research

To help the scholars with their research, Shawn Hill, an instructional technologist in Fordham’s department of informational technology, delivered a workshop in November that walked participants through the reference tool Zotero. The bibliographic and citation tool makes it easier for scholars to organize papers, monographs, books, and articles.

He also demonstrated Art Steps, a tool used by interior designers, art historians, and gallery managers to create virtual exhibits.

“You may have a painting in Kyiv, a sculpture in Kharkiv, and something in Odesa. You can’t bring them together in the real world for obvious reasons, but you can create an Art Steps exhibition space and give the URL to a guest or a friend or the public as a whole.”

My Soul Is Still There

Lyudmila Sholokhova, Ph.D., Curator of the Dorot Jewish Collection at the New York Public Library, grew up in Kyiv, and like Batanova, she worked at the V. Vernadsky National Library before moving to the United States.

In 1997, she was the recipient of a fellowship and spent time at the United States Library of Congress. Now she’s the point person for the fellows in the program working with New York Public Library.

The fact that she’s able to now help other scholars from Ukraine moves her deeply. “My soul is still there. I want to help my people in any way possible. I want to support them,” she said.

“I know the value of access to all these enormous resources that these libraries can provide. When I was in Ukraine, I had access to the primary sources, but I didn’t have access to scholarship on the documents,” she said.

“When you work on this subject, you really need the context. You really need access to a much larger corpus of resources.”

]]>This was the challenge that a panel of experts—together with one Holocaust survivor—addressed at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus on Jan. 26.

The event, “Remembering: Talking About the Holocaust in the 21st Century,” took place on the eve of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which commemorates the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp on Jan. 27, 1945.

Fred de Sam Lazaro, a correspondent for PBS NewsHour and director of the University of St. Thomas’ Under-Told Stories Project, moderated the evening, along with Peter Osnos, founder of PublicAffairs Books.

The discussion began with a screening of de Sam Lazaro’s 2022 PBS NewsHour segment on Nicky & Vera: A Quiet Hero of the Holocaust and the Children He Rescued (Norton Young Readers, 2021). Written and illustrated by Peter Sís, who was in the audience at the Jan. 26 event, it tells the story of Nicholas Winton, known as the “British Schindler,” who helped 669 children escape from Czechoslovakia just before the Nazi occupation.

One of ‘Winton’s Children’ Shares Her Story

One of those escapees, Eva Paddock, was interviewed by de Sam Lazaro at the event. She spoke just before the panel of experts addressed diminishing public awareness of the Holocaust amid a rise in disinformation and revisionism. In 1939, when she was 4, Paddock and her sister were placed by their parents on the last Kindertransport train leaving Prague and taken in by a foster family in England. Unlike the majority of “Winton’s children,” as they came to be known, Paddock was reunited with her parents in 1940.

Because she was so young, she needed people like her parents to help her fill in the gaps in her memory, she said. When they talked about their experiences, they did not dwell on the evil that drove them from their home, but on the gratitude they felt toward the British people.

She also shared the harrowing details of her father’s escape, which was made possible only because of the altruism of individuals, from an S.S. officer who looked the other way when he encountered him, to a stranger who paid for his flight from Brussels to London when he was told his Czechoslovakian money was no good with the country in enemy hands.

Educating Young People About the Holocaust

Holocaust education, which is mandated in schools in only 27 U.S. states, is due for a change, and her and her father’s stories should be a part of that change, Paddock said. Both stories show how even a single person has the potential to do enormous good.

“It has to come out of the history books and be made relevant to today’s generation, and I believe the way to do that is to reframe the way it’s taught,” she said.

“Certainly, it’s important to teach [people] to honor the millions lost, but I think it needs to be reframed to demonstrate the power of altruism and the power of one. Because of course, I look at Nicholas Winton, and here’s a prime example of the power of one.”

The panel that followed featured Judy Woodruff, senior correspondent, PBS NewsHour; Magda Teter, Ph.D., the Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies at Fordham; James Loeffler, Ph.D., the Jay Berkowitz Professor of Jewish History at the University of Virginia; and Linda Kinstler, author of Come to This Court and Cry: How the Holocaust Ends (PublicAffairs, 2022).

Their wide-ranging conversation touched on everything from the war in Ukraine and the 2017 “Unite the Right” white supremacist rally at the University of Virginia to the challenges faced by U.S. news organizations when newsworthy politicians use extreme rhetoric that was once beyond the pale.

Building a Framework for Memories

Loeffler said that when it comes to sustaining the memory of the Holocaust, it helps to remember that many people are involved—each with a different memory. This partly explains why Russian president Vladimir Putin could make the preposterous statement that Russia was invading Ukraine to fight Nazis and fascism, he said.

“One of our challenges is to build a frame so we can build an ethical response that takes the memory and brings people back together to understand what it was and what it wasn’t,” he said, noting that Paddock’s experience is instructive.

“When she was describing her own experience … she also talked about how her memory had been nursed and supplemented by people explaining to her her experience, describing things that had happened to her family and to her when she didn’t even remember,” he said.

“Memory is not just an individual flame that we nourish. It’s a social endeavor, and one of our challenges today is to figure out how we can rebuild that frame to make Holocaust memory relevant, and also build a common understanding of the past.”

Teaching About Events Leading to the Holocaust

Teter said that discussions with her students have convinced her that it might be better to place more emphasis than in the past on the lead-up to the events of the Holocaust. It’s something she does already and feels strongly about its value.

“That is what makes it relevant because they can see the processes, they can see the mental frameworks, they can see the media environment, the propaganda work that resonates with them, and the world that they are living in,” she said.

“It doesn’t just spring up in 1933. This is an outcome of a longer process. We need to recalibrate that story to include that longer story too.”

Unreliable News Sources with a Platform

Complicating the effort to recalibrate the way that the Holocaust is taught is the fact that those who would muddy the waters with obfuscation and ambiguity have access to more communications tools than in the past. Woodruff said journalists at NewsHour have had to come up with a new construct over the last several years to cope with the shattering of the traditional news delivery model.

“How do you both cover the news, be fair, cover it all, and call out something that is not the truth, that is a lie? I will tell you flat out, I’ve had difficulty with that,” she said, because she believes you cannot call someone a liar unless you know what’s in their heart and mind, an admittedly tricky endeavor.

She and her colleagues have adjusted by explicitly labeling false information as such. But given the plethora of news sources available online now, more responsibility has fallen on us as individual consumers.

“There’s a much larger burden placed on news consumers to figure out, ‘Can I trust this, can I believe this? How do I know?’ she said.

“We’re living in a much more complex, complicated moment when it comes to understanding what to believe.”

The event, which was livestreamed, can be viewed in its entirety below.

]]>“I don’t want to leave Kyiv. I was born here. I love Kyiv. Kyiv is the most beautiful city in the world,” said Vitaly Chernoivanenko, Ph.D., a Ukrainian scholar who spoke at a Fordham virtual panel on March 17. “I’m not afraid of Putin and his military forces.”

The panel is part of a new Fordham initiative designed to help Ukrainians during the Russia-Ukraine war. Fordham’s Center for Jewish Studies is co-hosting a virtual lecture series that discusses how the current crisis is affecting academia and co-sponsoring a fellowship program for Ukrainian scholars. The center is collaborating with three organizations: the American Academy for Jewish Research, the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in Germany, and the Lviv Center for Urban History in Ukraine.

“With people in war zones and in exile from their homes and in need of basic supplies, it may not seem urgent to give attention to scholarship. Nevertheless, society also depends on those who create and preserve knowledge through their scholarship, work, and institutions devoted to research and culture,” said Magda Teter, Ph.D., Fordham’s Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies and a professor of history who is moderating the lecture series.

The first lecture featured two Ukrainian scholars: Chernoivanenko, a senior research fellow at the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine and president of the Ukrainian Association for Jewish Studies, and Sofia Dyak, Ph.D., a historian and director of the Lviv Center for Urban History. The panel was moderated by Teter and Iryna Klymenko, Ph.D., a European history scholar from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

‘We Don’t Think About the Office or Our Laptops. We Think About People’

Chernoivanenko reflected on how the past three weeks have affected his professional and personal life. As a scholar who specializes in Jewish studies, preserving the work of his predecessors and colleagues is important, he said, especially in Ukraine, where his scholarship was once banned under Soviet rule.

“It’s a miracle that for these 30 years since our independence was proclaimed in 1991, we have a very prospective field … All these scholars sincerely want to research Jewish heritage of Ukraine and Eastern Europe,” said Chernoivanenko, who established the first Ukrainian peer-reviewed journal in Jewish studies and the first master’s degree program in Jewish studies in Ukraine. “It’s very important to preserve this heritage, especially now during the war.”

Chernoivanenko said many of his colleagues are still in Ukraine, where they are doing what they can to help with the war effort.

“We don’t think about the office or our laptops. We think about people, our colleagues,” said Chernoivanenko, speaking from Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine.

Chernoivanenko said he has been assisting local defense forces and strangers in the streets, including the homeless population. He added that he is thankful for his colleagues across the world who invited him to flee Ukraine by taking scholarship positions in their schools, but he said he wanted to stay home and help. His father and mother, who are 74 and 73, respectively, aren’t fleeing either, he said.

“My parents are very brave,” he said. “They said no, never. We believe in our military forces.”

Protecting Heritage and New Priorities

Scholars in Ukraine and those who have fled the country both need support, said Teter and Klymenko. There are opportunities that can help scholars who live anywhere, like the new fellowship co-sponsored by Fordham’s Center for Jewish Studies and the American Academy for Jewish Research, said Teter, which consists of a $5,000 stipend, remote access to library resources, and networking with faculty members from both institutions. Klymenko added that her own university’s history department has been providing financial aid and refuge for displaced Ukrainian scholars in Germany. Most of the refugees are women with children and elderly parents, she said.

“These are people, mainly scholars, who are basically trying to save their children from being further traumatized,” said Klymenko, who is affiliated with the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in Germany.

The war has also changed people’s views on the preservation of heritage, said Dyak, director of a research institution in Lviv, Ukraine. Her colleagues have been wondering whether or not their artifacts should be wrapped, hidden, or moved. They have also accommodated their facilities to the realities of wartime, she said.

“We turned our conference room and cafe into shelters … We are discussing [playing]cartoons and classic films for kids, but not home movies because that would be very painful. The shelter is for people who lost their homes or probably can’t go back to their homes,” Dyak said.

A Silver Lining and Hope

There is a silver lining within the chaos of the current crisis, said Teter.

“It is terrible that a war had to happen, but it puts your voices out there and makes the world discover the amazing scholarship that is being produced in Ukraine and your centers and institutions,” Teter said, directly addressing the panelists.

It is unclear when Ukrainian scholars will continue their partnerships with Russian scholars and institutions, said Dyak. She added that the path to collaboration will require much introspection on Russia’s part.

“Cultural arrogance can lead to violence,” Dyak said. “I am hopeful that in the future, from our shared experiences, we will be able to revisit, in a new way, conversations that are painful and hard … Right now we probably are not able to pick up these conversations, but I do hope that these shared experiences will create a space of trust.”

The second lecture will be held this Thursday, March 24, at 10 a.m. EST. Watch a full recording of the first lecture below:

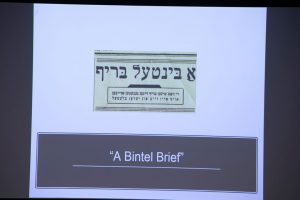

]]>Ayelet Brinn, Ph.D., Rabin-Shvidler Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, posed these questions to the audience in her lecture about the American Yiddish press at Lincoln Center on Feb. 13.

Brinn, who was introduced by Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies and professor of history Magda Teter, Ph.D., said that before talking about the significance of advice columns in Yiddish newspapers, it was important that the audience “think about the various ways people read and interact with advice columns and the fact that this is a media that is set up to be read by different readers in different ways.”

The Rise of the Yiddish Press in America

Yiddish speakers in the United States increased significantly in the second half of the 19th century with a wave of mass immigration from Eastern Europe, and by the 1920s, Yiddish newspapers were a popular option for immigrants seeking guidance in their new home. Many Jewish immigrants never read newspapers before coming to America, said Brinn, but they began to see them as an indispensable part of their lives for three reasons.

First, they helped acclimate readers to American life. Second, they created a sense of community by binding Yiddish readers to each other based on what they read. Lastly, they taught people who didn’t normally read newspapers that they could be informational and provide guidance on how to navigate their daily lives.

A good example, she said, is A Bintel Brief, which was one of the most popular advice columns of its time. Abraham Cahan, the longtime editor of the Forward, the most popular Yiddish daily, introduced A Bintel Brief to the paper in 1906, after asking readers to write to the paper with stories from their lives in the hopes of encouraging their relationship with the newspaper.

One letter in particular peaked Cahan’s interest, Brinn said. Written by a housewife, the letter sought the paper’s advice on how to confront her neighbor, who she suspected had stolen and pawned her husband’s watch. Interestingly, the woman was not upset, but “described her empathy for the poverty that drove her neighbor to steal, recognizing that this neighbor was also a poor worker,” she said.

Cahan was excited by this letter because it was written by an underserved demographic that he wanted to attract to the paper, and the emotional aspect of it was exactly the type of content he was looking for to better model his paper after American papers.

Success Brings Controversy

As A Bintel Brief began to increase in popularity, the authenticity of its letters was called into question. “Many Yiddish journalists, especially his loudest critics, assumed that the improvements editors made to Bintel submissions went beyond the correction of language and extended either to rewriting submissions or even fabricating letters when the Forward did not receive letters that fit the themes Cahan or his staff wanted to explore,” Brinn explained.

Since not all submissions were printed and the submissions were never kept in records by the Forward, there isn’t enough evidence to support either claim that the letters were real or fake.

“I’m inclined to believe that the truth lies somewhere between these extremes,” Brinn said. “Some letters were fabricated, some were real, and most letters that were real were significantly edited by the Forward staff.”

During a Q&A session after the presentation, an audience member confirmed that they had friends who actually read columns such as A Bintel Brief, and noted that “it didn’t really matter to those people if the letters were true or if they weren’t true. The advice didn’t matter either. It was really entertainment.”

Brinn heartily agreed.

“I think that one of the really important things about advice columns is that people could read them in all of these different ways,” she said.

“They did offer people advice that they could use in their lives, but other people could read these same columns for entertainment purposes.”

Freedman joined Fordham in 2007 as senior vice president for academic affairs and chief academic officer. He was appointed provost in 2010.

“For more than a decade, Stephen served Fordham tirelessly. He was known for his devotion to the faculty, students, and the academic community, and for his commitment to research and a global university,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham.

“He was a warm and insightful friend and colleague, and a man of deep conviction and rectitude. Stephen’s death is a grievous loss not just for his family and Fordham friends, but for everyone who knew him. We will miss him terribly.”

As provost, Freedman oversaw the operations of the University’s nine schools as well as the Fordham Libraries, Fordham University Press, WFUV, institutional research, prestigious fellowships, and Fordham’s efforts in international education.

Pioneering Partnerships at Home and Abroad

Freedman saw tremendous potential in establishing and strengthening partnerships between Fordham and other world-class institutions, whether they be across Southern Boulevard in the Bronx or across the Atlantic in London.

A professor of ecology and evolutionary biology in addition to his role as provost, Freedman was instrumental in forging the Bronx Science Consortium—a research partnership between the University, the Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Yeshiva University, the Bronx Zoo/Wildlife Conservation Society, Montefiore Medical Center, and the New York Botanical Garden. The consortium offered numerous hands-on opportunities for undergraduate and graduate students to collaborate with some of the top researchers in the world.

Further abroad, he oversaw the progress of Fordham’s new London Centre campus, set to open this fall. In December 2017, when the University signed the lease on the new space, Freedman noted the many possibilities for scholarship beyond the traditional semester abroad.

“London will not merely be a campus for Fordham students to study away,” he said, “but a destination for students from other universities across Europe and Asia, and a hub of global scholarship. London, and our programs in Beijing and Pretoria, are templates for expanding the Fordham mission outside of New York City, and outside of the United States.”

Freedman traveled extensively on Fordham’s behalf, overseeing the University’s international programs—and developing new ones. In May, he led the first Fordham Faculty Research Abroad Program at Sophia University in Tokyo. That same month, he celebrated the 20th anniversary of Fordham’s Beijing International MBA (BiMBA) program in China.

International Strategy

“He would often say that one of the responsibilities that the board gave him when he became provost was to develop an international strategy for Fordham, and so he took that seriously,” said Jonathan Crystal, Ph.D., interim vice president and chief academic officer in the Office of the Provost.

“He was incredibly innovative in establishing partnerships, online learning … he was a visionary. He was not stuck in the traditional ways of thinking about higher ed. He was really committed to making Fordham a global institution,” said Crystal. “He also put a lot of importance in his mentoring of me and other administrators and faculty at Fordham. … He was just incredibly selfless. He had so much heart.”

Ellen Fahey-Smith, associate vice president and chief of staff in the Office of the Provost, said Freedman “touched the hearts and minds of friends and colleagues throughout the world.”

“His legacy will endure in the transformative academic excellence he has insisted upon at Fordham, a place he cherished and called home,” said Fahey-Smith, who worked with Freedman for more than 10 years. “I will miss him deeply.”

‘A Deeply Spiritual Man’

Freedman worked closely with his faculty colleagues to develop new ideas and initiatives at home as well as abroad.

“He was very committed to the faculty,” said Magda Teter, Ph.D., the Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies and professor of history at Fordham. “Once a faculty member too, he understood our work and the challenges we face. He was very strongly supportive and extremely warm,” she said through tears.

Teter said Freedman was “one of the key figures” in the development of Fordham’s Jewish Studies program, which Teter directs. She also said he was extremely proud to be the Jewish provost of a Jesuit university.

“He would always bring it up as a mark of pride in Fordham. He felt it spoke volumes about Fordham and its ethos of inclusion,” she said.

“He was a deeply spiritual man. When we were in Jerusalem together in 2016, it was a deeply moving experience for him, even though it was not his first time,” she said. “That’s why it worked for him to be a provost at Fordham—that commitment to faith.”

When he joined the Fordham faculty in 2007, Freedman told FORDHAM magazine that he’s “always seen science and religion as complementary.”

“My own scientific and religious backgrounds have enhanced each other, and I think informed discussions between theologians and scientists play a critical role in the shaping of ideas,” he said.

A native of Montreal, Freedman earned a B.S. from Loyola of Montreal, an M.S. in environmental studies from York University in Toronto, and a Ph.D. in ecology and evolutionary biology from the University of California at Irvine. He also completed the United Nations Graduate Study Program in Geneva.

He has spent nearly his entire career at Jesuit Universities; for 24 years he was at Loyola University of Chicago, where he taught biology and served as dean of Mundelein College. From 2002 until 2007, he was academic vice president at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington.

Freedman is survived by his wife, Eileen; his sons, Zac and Noah; and his grandson Aaron. Fordham will hold a memorial service to honor him in the fall.

Feature photo by Chris Taggart

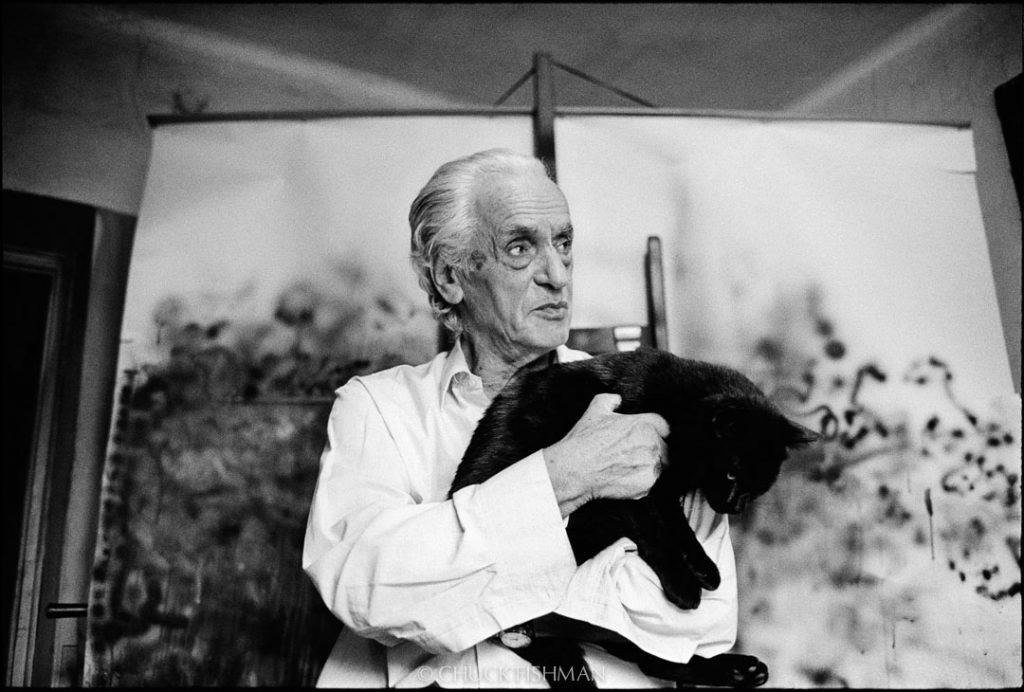

]]>After a 30-year hiatus, he returned to document a stunning reversal of history—a Jewish cultural renaissance emerging and expanding into the mainstream of 21st-century society. He will document this revival in a photographic exhibit, Roots, Resilience, Renewal.

Wednesday, May 3

6 p.m.

School of Law Room 1-01

150 W. 62nd St., Lincoln Center Campus

The show draws upon Fishman’s first monograph, Polish Jews: The Final Chapter, (McGraw-Hill, 1977), and represents a project spanning 40 years—from the near-demise to the transformative rebirth of Polish Jewry.

Magda Teter, Ph.D., Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies at Fordham, said Fishman’s early images, which are considered rare and historically unique, chronicle an era long left to memory, and serve as notable counterpoints to his latest work, which illuminates and defines the myriad faces and facets of a Jewish ‘return’ to identity today.

“This is a story that offers us a rare perspective into an exceptional moment in time, one that the passing of four decades has radically changed,” she said.

A four-time winner of the World Press Photo Foundation Medal, Fishman has published photographs on the covers of Time, Life, Fortune, Newsweek, The London Sunday Times, and The Economist. His photos are represented in the collections of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Center for Creative Photography, Hogan Jazz Archive, Studio Museum in Harlem, POLIN: The Museum of the History of Polish Jews, and the United Nations.

The event is jointly sponsored by Fordham’s Jewish Studies program; the Derfner Judaica Museum, and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

For more information, contact [email protected] or visit fordham.edu/jewishstudies.

“It’s very exciting and it strengthens our connection with another major cultural institution,” said Magda Teter, Ph.D., Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies and professor of history.

The Fordham-NYPL Fellowship Program in Jewish Studies is made possible by the Eugene Shvidler Gift Fund and additional gift funds to Jewish studies.

“The library has quite a number of fellowships, but there’s not something special for the Dorot Division,” said Stephen D. Corrsin, Ph.D., curator of both the Dorot Jewish Division and the Slavic, Baltic, and East European Collections.

The Dorot Division was formed two years after the library was founded in 1895 and was the library’s first special collection, he said. With over 300,000 books and serials, it stands as one of the most significant collections of Judaica in North America.

“I know that scholars will find all sort of things here. Sometimes it’s serendipitous, sometimes they’re looking for something specific,” he said.

From a collection of 15th-century books published at the dawn of the printing press called incunables to microfilms of 20th-century Jewish newspapers from around the globe, the library presents a rare chance for scholars to study materials that have yet to be digitized, Corrsin said.

“We get people dropping by who just want to see something unusual, and if we have a facsimile we’ll bring it out,” he said. “But we wouldn’t bring out an incunable for a tourist. The scholar has a presumed need for the original item.”

Teter said that while Fordham Libraries’ Archives and Special Collections continues to grow its Judiaca collection, the library doesn’t yet have the resources to support the world class Jewish scholarship that the Dorot Division can provide. But Fordham can now facilitate visas for international scholars to gain access to the division; in turn, the University will then showcase their findings at lectures and faculty seminars.

“Research in the humanities and social sciences is underfunded and this program will enable scholars who we would love to come to New York City to come and share their research,” said Teter. “The New York Public Library will be their research lab and Fordham will be the place where their exciting conversations happen.”

In addition to the fellowship program, the University will host its first joint Fordham-NYPL program on March 29 with a talk by NYPL Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center Fellow Natan Meir, Ph.D., on “Stepchildren of the Shtetl: Destitute and Disabled Outcasts of East European Jewish Society, 1800-1939.”

But he always knew he wanted to leave his native Turkey to study here, and Fordham’s Bronx campus had a special appeal to him: Gültepe, the area of Istanbul where he lived, translates as “Rose Hill” in English.

He said the United States’ traditions of freedom of religion, inquiry, and speech were things that drew him here.

“In Turkey we are so divided politically, there is no space for talking freely,” he said.

After dabbling in courses in sociology, anthropology, archeology, and history, Kilicarslan, who is Muslim, is leaning toward a Middle East studies major. He’s already declared a minor in Jewish Studies, the first student at Fordham to do so.

Kilicarslan developed a particular interest in Judaism after having taken two courses: Jews in the Ancient and Medieval World, and History of Modern Judaism. He’s enrolled this semester in East European Jewish History, and last month he became Fordham’s first intern in the Museum for Jewish Heritage’s interfaith program.

As part of the internship, he helps facilitate dialogue between Muslim and Jewish elementary school students.

“In Turkey, I didn’t have a chance to study or even read about Jews and Christians. I had only some illusions about them, and some superficial knowledge. My goal here is to really understand these different cultures,” he said.

Magda Teter, Ph.D., the Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies and professor of history, called Kilicarslan “one of the most exciting and intellectually promising students” that she has met in 15 years of teaching. She’s added new images, maps, and study quotes to her courses in Jewish history course as a result of his queries.

“Since he’s coming from the Muslim tradition, in which the Qur’an was transmitted in Arabic— and not in different versions and translations as biblical texts were—he’s asked very poignant questions about the process of establishing scriptural canon, and about its fluidity,” she said.

“Some of his most thought provoking questions have led me to change the direction and focus of the course I’d taught for over a decade.”

Kilicarslan said one benefit of learning about Christianity and Judaism is that it helps him better understand his own faith. The Qur’an references Jews and Christians, he said, and he sees no reason why they can’t all live together peacefully. The conflicts and persecutions among members of the three faiths has tended to be the result of economics, or political interests or aspirations.

“I’m interested in the complex situations among different groups, and in finding solutions for these situations. What I see is that, like me, a lot of people have [to overcome]a superficial understanding of others.”

“When people of different faiths focus on our common ground and wisdom, such as accepting the same God, seeing violence as unfruitful, and the existence of compassion and love in all three traditions, our tensions will decrease,” he said.

]]>