“The U.S.-Mexico borderlands is a place where the Earth just swallows up bodies,” says Leo Guardado, Ph.D.

He doesn’t mince words about the humanitarian crisis at the border. In May, 144,278 migrants were taken into custody by the U.S. Border Patrol, the highest monthly total in more than a decade. And each year, the agency finds hundreds of corpses—the remains of men, women, and children who died traversing the vast desert and mountain regions on both sides of the dividing line.

The Trump administration’s efforts—separating migrant parents and children, deploying U.S. troops to the border, sending asylum-seekers to Mexico to await immigration court hearings—have not reduced the number of people fleeing poverty and violence in Central America to enter the U.S. without authorization.

Guardado knows all too well the pain and fear that families suffer when making the dangerous decision to migrate to the U.S. He was just 9 years old in 1991 when he and his mother made the nearly 3,000-mile trek from their mountain town in El Salvador.

Today, he is an assistant professor of theology at Fordham. And while the federal government remains deeply divided on how to handle the crisis, he views it not as a political abstraction but as a theological issue.

A Migrant’s Journey

Guardado was born in a rural town in northern El Salvador during the country’s civil war. As he approached his 10th birthday, his mother feared that he would soon be conscripted by the army or the guerrillas.

She was determined to move him from harm’s way. Family in the U.S. loaned them money, and Guardado said his grandfather probably sold what little cattle the family had to help pay for his and his mother’s journey. He remembers crying with his grandfather as they said their goodbyes, both of them knowing they might never see each other again. And they never did.

“We got on a bus, and I counted palm trees,” Guardado said. He learned two English phrases from his mother—“‘Thank you,’ ‘I’m sorry’—how to be grateful and how to ask for forgiveness,” he said. “These were the only two phrases that I had in my English vocabulary leaving El Salvador.”

He thinks he counted palm trees as a way of remembering his country. By the time he reached the hundreds, he fell asleep. He awoke in Guatemala, and from there his memory skips through a series of glimpses, mostly involving walking: “A lot. Many days. Under the moonlight.” He traveled with a group of about 15 migrants who followed a “coyote,” a paid guide, for the length of the journey.

He remembers being crammed into false compartments of trailers, packed together “like sardines” for five hours at a time. In Tijuana, they crossed beneath a barbed-wired fence patrolled by jeeps, and in darkness jammed into a small taxi like a “clown car,” which took them over back roads to a white van that ultimately brought them to San Diego.

He and his mother eventually connected with family in Los Angeles, where Guardado was educated by the De La Salle Christian Brothers at Cathedral High School. He earned a full scholarship to attend Saint Mary’s College of California, and it was in his first year there that he finally received legal residency status. He became a U.S. citizen in 2010.

Religion, Politics, and Sanctuary

Saint Mary’s is not far from a Trappist monastery, where Guardado spent a year before earning a master’s degree in theology at the University of Notre Dame. For two years, he directed the social justice ministry at a Catholic church in Tucson, Arizona. Then he returned to the monastery for what he thought would be the rest of his life. But there, in isolation, ideas began to “percolate,” he said, and he returned to Notre Dame, where he earned a doctorate in theology.

He initially studied early church history, but his focus changed after he took a course with Gustavo Gutiérrez, O.P., the father of liberation theology, which emphasizes the perspective of the poor.

“I began to crack open the possibility that my own experience, my community’s experience, and the historical reality of Latin America—poverty, oppression, war, violence—that all of this was raw material out of which I could do theological reflection,” Guardado said.

In his dissertation, he wrote about the 1980s sanctuary movement, when hundreds of Catholic churches provided a safe haven for refugees from Central America. Today, he said, only a handful of churches in the U.S. are willing to take that risk. He said bishops will often say providing sanctuary is illegal or too political.

“The term sanctuary often mistakenly gets reduced to politics,” he said. “In light of human displacement worldwide and 11 million undocumented here in the U.S., if we’re to be a church of and for the poor, then you can’t just say ‘no.’ You have to engage with the question theologically. Otherwise, one can argue that it’s an ecclesial sin of omission.”

Guardado said the point of theology is not just to “do religious metaphysics” but to deal with contemporary issues head-on. He is developing a course on migration and theology that will include a visit to the U.S.-Mexico border.

“I want my students to ask: How does theological thinking change the world? How does it change history? How does it leave an impact so that it’s not just thinking about God but actually aims to transform the world?”

Bearing Witness at the Border

Guardado is far from being the only Fordham professor engaging with the humanitarian crisis at the border.

During spring break in March, a group of 10 faculty members went to see it for themselves. They visited the Kino Border Initiative, a consortium of six Catholic organizations in the border city of Nogales—both on the Arizona side and the Sonora, Mexico, side—that serves deportees and asylum-seekers and promotes a spirit of international solidarity.

Faculty members raised $13,000 to buy toiletries and necessities for the migrants, and Fordham’s Office of Mission Integration and Planning funded the trip. Michael C. McCarthy, S.J., vice president for mission integration and planning, said it was a necessity, given how migration is now a major global challenge.

“Because this is such a major social issue and it impacts questions of justice, what we want to be as a society, and how a place like Fordham, as a Jesuit university, tries to develop students, we decided the border would be a great site for this immersion experience for a diverse group of faculty members,” he said.

Jacqueline Reich, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Communications and Media Studies, and theology professor James McCartin, Ph.D., acting associate provost of the University, co-led the trip.

It was the second time Reich went to Nogales, having worked with the Kino Initiative in January 2018. Although only 14 months had passed, the experience was very different, she said. As before, the group stayed overnight in Arizona and crossed the border to work in a comedor, or cafeteria, in Mexico, that provided meals to people waiting for asylum claims to be heard in the United States.

In 2018, she said, they would typically have one seating of 40 to 50 people—mostly men, a few women, and very few unaccompanied minors. This time, there were multiple seatings with 300 people per meal.

“We spent a lot of time holding babies while people could eat, or entertaining children, or sitting and talking to groups of families that had left Honduras, Guatemala, or regions of Mexico that were affected by gang violence and poverty,” she said.

In addition to serving meals, the group hosted a party at a women’s shelter, met with Border Patrol agents, and hiked along the border to understand the conditions there.

They also attended an “Operation Streamline” hearing in Tucson, Arizona, where immigrants appeared in a group before a judge, who often deported them for being in the U.S. illegally after asking two quick questions.

Glenn Hendler, Ph.D., a professor of English and American studies and acting chair of the English department, said he was surprised to learn that a wall was constructed through the middle of the city of Nogales in 1994, long before President Donald Trump made building a border wall his signature campaign promise.

Although he does not speak Spanish, he was able to connect with a 6-year-old girl at the comedor whose father was washing dishes nearby.

“It was an incredible joy to make a child who was going through a horrific experience laugh,” he said. “The next day, we were serving a meal, and I heard a little girl yelling ‘hola, hola,’ and it was the same little girl again. She was happy to see me, and I was happy to see her. But there were so many people there that they just got rushed out, so I never got to say goodbye to this little girl. For some reason, that just broke my heart.”

Speaking with the Border Patrol complicated the picture for Hendler because it showed how difficult the job is, he said. But it did not change his mind about the moral implications of the situation. In fact, he said that by then he felt more emotionally connected to what had previously been an abstract concept.

‘Accompany, Humanize, Complicate’

Carey Kasten, Ph.D., associate professor of Spanish, was moved by learning specific details of the migrants’ experience, like why black water bottles are a must for those crossing the border at night. (They don’t reflect moonlight.) “We were told to accompany, humanize, and complicate,” she said. “To see those real items that our guide had collected on hikes through the desert, and also to see people get out of a van who’d been deported and go into the soup kitchen we were working in [in Mexico], was something that really stood out.”

McCartin, the theology professor who co-led the trip, recalled a conversation with a man from Honduras who asked if all Americans consider him and his fellow migrants to be criminals. “I said, ‘Oh gosh, no, I have no problem with you.’ This guy was like, ‘Really? I can’t believe that.’ I said, ‘No, I can see how you have a sense that that’s how Americans talk about you, and there are plenty of them that do, but there are also a lot of us that don’t really begrudge you trying to have a better life,’” he said.

“This moment of his being surprised that we’re not unified in our attitudes toward people at the border—a lightbulb went on for this guy, and I’ll remember that.”

—Story co-author: Patrick Verel

Guardado is teaching “Christian Mystical Texts” at Fordham College at Lincoln Center and will be teaching a doctoral seminar in the fall. He is also developing a course for next year on migration and theology that will include a visit to the border.

He doesn’t mince words when it comes to his thoughts about the humanitarian crisis at the border. He knows all too well the pain families suffer when making the dangerous and painful decision to leave their home countries and migrate to the U.S. He made the nearly 3,000-mile trek when he was just 10 years old.

“Every year we have hundreds of remains that are recovered from there and so I have problems with the indifference of the church on this issue,” he said. “And by church, I mean the people of God, I mean the institutional church, but I also mean more than just Catholics. I mean the body of Christ in history that we claim to be—all of it.”

As the federal government sits in a stalemate about the fate of the border, each side claiming humanitarian concerns, Guardado views the crisis as a theological issue, not a political abstraction. He has spent years returning to help migrants in an area he knows all too well from his childhood. It’s a journey that propelled him from Los Angeles to the cloisters of a Trappist monastery, and now, to the halls of academia. But, in the end, he’s never really left the border.

“There are just so many forces coalescing at the border and such a rawness of the human experience that those are some of those questions I ended up taking to the monastery, and I think in the monastery those questions perhaps pressed themselves more fully upon me,” said Guardado, who started at Fordham last spring. “And that indirectly led me back to consider that maybe I have a lot more learning to do about deep questions of how the mystery of God, church, and faith intersect and can shine light upon of some of the ills of our world.”

The Journey

Guardado was born in El Salvador in the midst of the country’s civil war. As he approached the age of 10, his mother knew full well that he could be conscripted by either the army or the guerrillas. She was determined to move him from harm’s way. He said his grandfather probably sold what little cattle they had to pay for the journey, along with other monies lent by family in the U.S. He remembers his grandfather crying as they said their goodbyes, both knowing they might never see each other again. They never did; his grandfather died in the years that followed.

“We got on a bus and I counted palm trees, said goodbye to family, a lot of tears,” he said. “I knew two phrases that my mom knew: Thank you. I’m sorry. How to be grateful and how to ask for forgiveness. These were the only two phrases that I had in my English vocabulary leaving El Salvador.”

He said he thinks he counted palm trees as a way of remembering his country. By the time he got into the hundreds, he fell asleep and woke in Guatemala. From there his memory skips through a series of glimpses, built mostly of walking: “A lot. Many days. Under the moonlight.” The group of about 15 migrants followed a paid guide known as a “coyote,” or “coyota” in their case, as she was a woman. She stayed with them for the length of the journey. It’s a model of migration that no longer exists, he said. Today’s migrants are passed from one person to another, a series of small transactions on a journey through the hemisphere.

“It’s much more dangerous in that sense [today]and on many other levels,” he said. “That lady was with us, even if she would leave for a day or so, she would be back the next day and arrange the next stage of the journey.”

The group crammed into false compartments of trailers packed together “like sardines” for five hours at a time “hoping that thing doesn’t turn over because if it does you’re probably not going to make it out alive.” They spent a night in jail and were bailed out by the coyota.

“You paid people along the way, as needed. The federal officers, the police. They understand that you’re leaving and why you’re leaving,” he said.

In Tijuana, they crossed beneath barbed wired patrolled by jeeps. At 2 a.m. they jammed into a small taxi like a “clown car.” They traveled through backroads to a white van. Finally, Guardado got to sit up front and ride shotgun because “no one will think anything of it, he’s just like a U.S. boy.” Soon he saw Los Angeles.

“My closest neighbor in our Salvadoran village was a quarter mile away and in between were hundreds of trees and wilderness. So, arriving in L.A., where every so often there’s a street light and each house has the same amount of space between it, it just felt so artificial. It just felt like, ‘Wow. Where’s the beauty of the chaos?’”

The Calling to Monastic Life

Guardado was educated by De La Salle Christian Brothers in L.A. and then moved on to St. Mary’s College of California. The college was not far from the Abbey of Our Lady of New Clairvaux, a Trappist monastery whose abbot at the time was formed by Thomas Merton, the prolific writer and Catholic theologian. The abbot, Thomas Davis, O.C.S.O., had structured the monastery around the teachings of Merton.

“He [Merton] had this cultural and artistic sensitivity, intellectual sensitivity, and curiosity that he passed on to someone like Father Thomas Davis, so I fell in love with that vision of the monastery,” he said.

Guardado began to view the abbey as a way to question the commodified society surrounding him. To this day he cannot explain his calling. “It was a mystery,” he said. But he added that the simplicity of monastic life was “a form of resistance to U.S. values that emphasize upward mobility.”

“It’s less about being in charge of the reflection, but just allowing for a deconstruction of the self, and what emerges is something else,” he said of the prayerful silence.

After an initial year at the monastery, he began a journey that took him to the University of Notre Dame to get a master’s degree in theology and then back to his alma mater, St. Mary’s, where he served as assistant director of justice education. He returned to the borderlands as director of social justice ministry at Most Holy Trinity Catholic Church, a progressive parish in Tucson, Arizona. Back at the border, in many Catholic churches he witnessed a “vast indifference” to the suffering he saw. After two years, he went back to the monastery for what he thought would be the rest of his life. But there, in isolation, ideas began to “percolate.”

His mentor knew more was in store for him.

“This place is too small for you, Leo,’” he said Davis told him. “I think you need to be open to the possibility that God may be calling you to a new place.”

He soon applied and was accepted back at Notre Dame for his doctorate.

“I didn’t want to live life wondering, ‘Should I have gone?’” he said, so he left the monastery.

Theological Reflection and Supporting Sanctuary

At Notre Dame, he began studying patristics—early church studies that reflected the readings that he immersed himself in at the abbey. But his focus changed after he took a course with Gustavo Gutiérrez, O.P., the father of liberation theology, which encourages the study of theology from the perspective of the poor. Guardado would go on to become an assistant to Father Gutiérrez.

“For a boy from Chalatenango, a village of El Salvador, I’ve found myself in pretty amazing circles,” he said.

With Gutiérrez, he took a doctoral seminar on Bartolomé de las Casas, a 16th-century Dominican friar who stood up to the Spanish government and the church in defense of the indigenous peoples.

“In this class, for the first time really, I would say, I got vocabulary about my own history growing up poor in a village in the mountains, without electricity, without running water, in the middle of a civil war in the midst of violence,” he said.

He began to examine the distinction between the early patristic church he had come to understand at the monastery and the 16th-century church of empire, war, and “commodification of bodies”—a church that even questioned the humanity of indigenous people. The class helped him question what theology is and what it could be.

“I began to crack open the possibility that my own experience, my community’s experience, and the historical reality of Latin America—poverty, oppression, war, violence—that all of this was raw material out of which I could do theological reflection.”

His dissertation, which informs a chapter he wrote for a forthcoming book, An Ethic of Just Peace (Georgetown University Press, 2019), examines the concept of sanctuary alongside theories of nonviolence. His primary focus is on the root of the sanctuary movement in the 1980s when hundreds of Catholic churches provided sanctuary to Salvadorian refugees. Today, he said, only a handful of churches in the U.S. are willing to take the risk. He said that bishops will often say providing sanctuary is illegal or too political.

Guardado said that his research attempts to provide theological justification for “sanctuary as an ecclesial practice.”

“The term sanctuary often mistakenly gets reduced to politics,” he said. “In light of human displacement worldwide and 11 million undocumented here in the U.S., if we’re to be a church of and for the poor, then you can’t just say, ‘No.’ You have to engage with the question theologically. Otherwise, one can argue that it’s an ecclesial sin of omission.”

But even here, Guardado taps the patristic period to back his arguments for sanctuary. He noted that the earliest mention of bishops providing sanctuary goes back to 343 at the Council of Serdica. Later that century in 399 the archbishop of Constantinople, John Chrysostom, gave shelter to a man named Eutropius who, ironically, had been a critic of sanctuary. The archbishop gave a sermon that took a jab at Eutropius and argued for sanctuary.

“You never know when you’re going to be the one who needs sanctuary,” Guardado said, knowingly.

“I understand this from my experience as a boy in El Salvador, but also my experience as a product of Latin America and its relationship to the U.S. and the world now.”

Those relationships are as fraught today as when he arrived, he said. And he acknowledges that it’s as impossible as ever to speak of the Latin American poor theologically without speaking about them politically.

“It is politics that creates the very structures that keep people down and that keep them dying out of injustice and other means, like lack of food,” he said. “You cannot deal, genuinely with the poor if you don’t deal with politics.”

Guardado said that the kind of theological work he does and wants to teach his students at Fordham is the kind of that deals with contemporary issues head-on.

“I want my students to ask: How does theological thinking change the world? How does it change history? How does it leave an impact so that it’s not just thinking about God, but actually aims to transform the world?”

He said that is the point of liberation theology, as well as a Jesuit education.

Echoing Gutiérrez’s words, Guardado says, “‘The point is not to do religious metaphysics. It is to figure out and to really reflect out of lived accompaniment with the poor, with the margins. How does our faith connect with that and how does it transform that reality?’”.

]]>The social-justice movement, which emphasizes solidarity with the poor, was championed by many Jesuits in Latin America at the time, and it made a deep impression on Fernández de Lahongrais. So when he was looking for colleges in New York, he was drawn to Fordham’s Jesuit mission.

Now, as a criminal defense attorney, he continues his commitment to social justice, often taking on pro bono cases in Washington, D.C., Boston, and his native Puerto Rico, where he still resides.

In late January, for example, he filed a complaint against the United States, demanding equal rights and obligations for U.S. citizens in Puerto Rico when it comes to federal funding for Medicaid, Medicare, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Disparities in funding, he argued, violate the equal protection clause of the Fifth Amendment and put vulnerable groups—the poor, the elderly, and children—at risk.

In the past year, Fernández de Lahongrais has also found time to pursue another passion: teaching.

Last fall, the 1987 graduate of Fordham’s Gabelli School of Business returned to Rose Hill to teach The Ground Floor, a course that introduces Gabelli undergrads to various business disciplines. It’s a class he is particularly well suited to teach. After graduating from Fordham, he passed the CPA exam and later earned an M.B.A. in finance.

“The kids were so smart, and so well prepared,” he said of his first teaching experience. He took his class on field trips to the New York Stock Exchange and Credit Suisse, and he added case studies to each section of the curriculum to help students get in-depth knowledge of the different career paths they could take.

Fernández de Lahongrais has stayed in touch with many of his Fordham friends since graduation—his college roommate is the godfather of one of his three children. But it was only a few years ago that he reconnected with his alma mater. He joined the President’s Council, a select group of alumni and parent philanthropists committed to raising the University’s profile. And one of his daughters, Sofía, is now a sophomore at Gabelli; last fall she helped spearhead some of the on-campus efforts to help victims of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico.

“We’re making Fordham our family university,” he said. “And I’m very happy to see where Fordham is going.”

Fordham Five

What are you most passionate about?

I’m most passionate about defending those who cannot defend themselves. I think the law is a beautiful thing, but it is sort of like a spiderweb. It’s beautifully intertwined and majestic, but it’s also great at catching the weak; the powerful can just punch through and break that spiderweb. That’s what I see every day, and it bothers me.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

To learn to write with my left hand. I really gave this advice to myself, but it changed everything. Right after Fordham, I joined the Navy. But just before leaving for Officer Candidate School, I broke my right hand, and they had to postpone my entry. I basically had nothing to do, so I decided to take the CPA exam. But I had to learn how to write with my left hand to study. And I did. That’s when I realized that there’s always a valid excuse not to do something, but the thing is, there’s always a way to do it anyway.

What’s your favorite place in New York City? In the world?

In New York, the Beacon [Theatre] and the Bowery. I love music, especially underground music and the old classics. I mean, I’ve seen so many great bands at the Beacon—like Hot Tuna and Elvis Costello—and on the Bowery. CBGB was a place I used to hang out when I was at Fordham. That’s where the Talking Heads and the Ramones started [in the ’70s]. It all reminds me of New York back then, when it was falling apart but it was very artistic.

In the world, Culebra Island. It’s actually part of Puerto Rico, but it’s still virgin land, virgin beaches, not really developed. It’s beautiful.

Name a book has had a lasting influence on you. Explain how and why.

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez. That book was so implausible. But the stories he was telling really described life in Latin America. He wrote about how some things never change, how we were stuck in time. And the way he wrote, I found it to be so magical, so incredible. He wasn’t telling me, he was showing me. That made me love to read literature.

Who is the Fordham grad or professor you admire most? Explain why.

Father McShane. He inspired me to give back to Fordham, and to do everything that I’m doing with the University. I also got closer to the church, because I had been disillusioned for a time. But seeing Father McShane and seeing our Jesuit pope from Argentina, I feel like things are changing.

“We’re living in a new moment of the history of the city,” said Father Galli, the dean of the theology faculty and director of doctoral studies at the Catholic University of Argentina. “In 1810, only London surpassed one million inhabitants. By 1910, 10 cities did. Today, there are about 500 cities worldwide with populations of larger than one million,” and more than 30 of these cities are “megacities,” with more than 10 million inhabitants.

Father Galli is a member of the International Theological Commission, a group of theologians who serve as advisers to the pope. He collaborated with Pope Francis for the final document of Aparecida, one of the main sources of Pope Francis’s vision.

Father Galli has been a close theological collaborator with the pope since the latter’s days as Jorge Bergoglio, SJ, archbishop of Buenos Aires. He is an expert on Lucio Gera, the father of teología del pueblo, or liberation theology, a school of theology that emphasizes a “preferential option for the poor” and has influenced much of Pope Francis’s pastoral ethos.

“We are called to meet the other—the known and unknown, the similar and the different,” Father Galli said. “Faith promotes a culture of urban encounter, and a Catholic university must be a school of encounter.”

He recalled the Madison Square Garden homily, in which the pope urged the faithful to notice those who go chronically unnoticed.

“Beneath the roar of traffic, beneath the ‘rapid pace of change,’ so many faces pass by unnoticed because they have no ‘right’ to be there, no right to be part of the city,” the pope had said.

“They are the foreigners, the children who go without schooling, those deprived of medical insurance, the homeless, the forgotten elderly. These people stand at the edges of our great avenues, in our streets, in deafening anonymity. They become part of an urban landscape which is more and more taken for granted, in our eyes, and especially in our hearts.”

The task of city-dwellers, whether in Buenos Aires or in the Bronx, is to draw those who are forgotten from the periphery to the center, Father Galli said. Local parishes can rely on the church’s guidance in going about this daunting task, but they ought to draw also on their own wisdom.

“[The idea is not] to return to centralism,” Father Galli said. “The pope does not want to impose from Rome—or from Latin America—a particular pastoral, urban model for a local church. Rather, the local church should hear his challenge and then find its own creative ways of exercising an urban pastoral ministry.”

The first step for faith communities in including the excluded, Father Galli said, is to “draw near to” them—to meet them at the peripheries.

“Only a church that can gather around the family fire remains able to attract others,” he said.

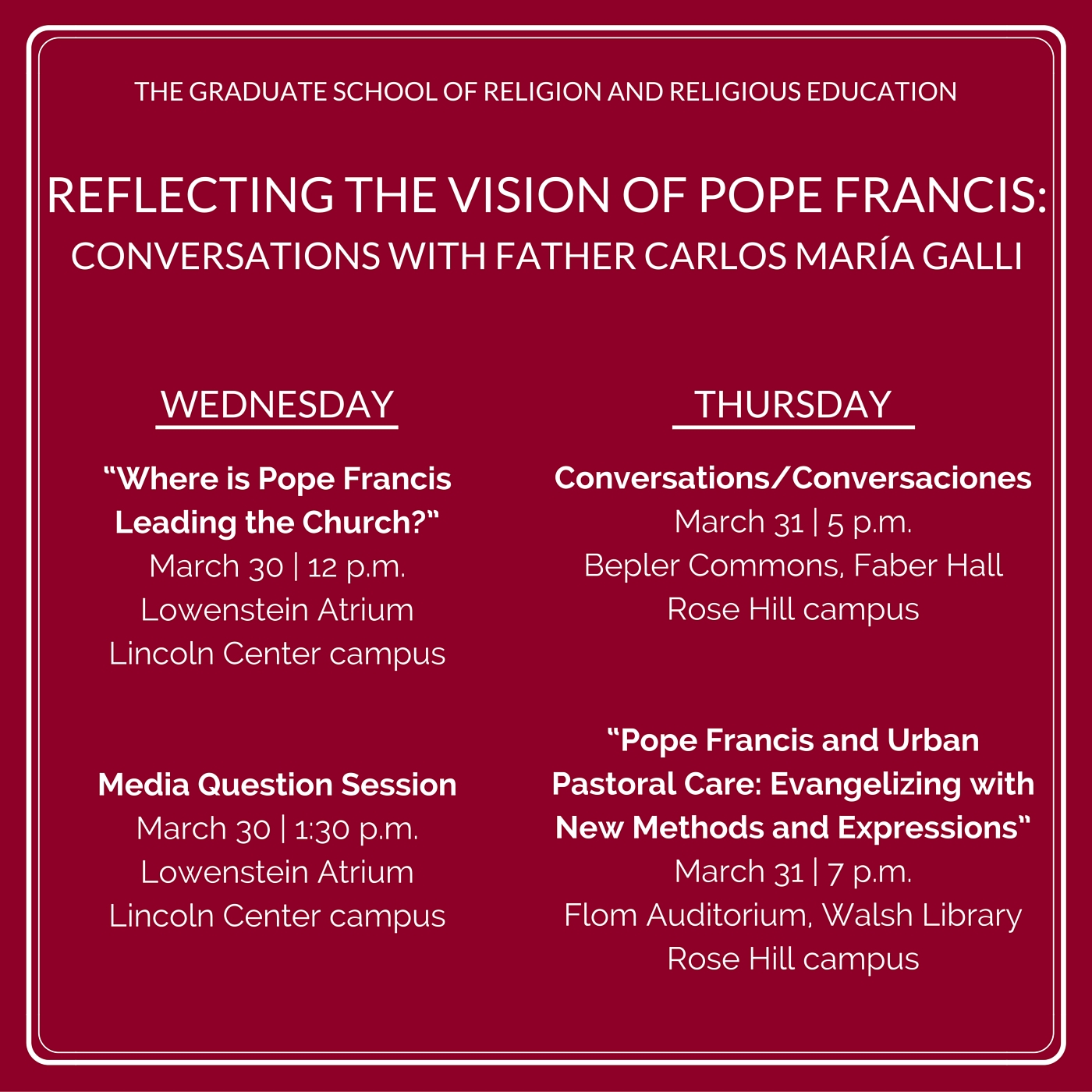

The March 31 lecture was the last of four discussions that Father Galli led on both campuses over a two-day visit to Fordham.

]]>Carlos María Galli, STD, a priest from the Archdiocese of Buenos Aires, will lead four discussions over the next two days on both the Lincoln Center and Rose Hill campuses. All discussions, which are sponsored by the Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education, are free and open to the public.

“Father Galli has been a close theological collaborator with Pope Francis from [the pope’s]days as archbishop of Buenos Aires,” said Claudio Burgaleta, SJ, associate professor at GRE. “His lectures at Fordham will provide a window into the pope’s theological influences, especially Argentina’s take on liberation theology.”

Father Galli is the dean of the theology faculty at the Catholic University of Argentina, where he also serves as director of doctoral studies. He specializes in the study of Lucio Gera, the father of teología del pueblo, or liberation theology. In addition, Father Galli has a long record as consultant to both the bishops of Argentina and the Episcopal Conference of Latin America (CELAM).

Shortly after his election, Pope Francis named Father Galli to the International Theological Commission, a group of theologians that serve as advisers to the pope. He collaborated with Pope Francis for the final document of Aparecida, one of the main sources of Pope Francis’ vision.

“Father Galli’s own thought makes a contribution to pastoral urban theology—ministry of the city and to the city. He argues that the nature of cities is such that they demand a new form of evangelization,” Father Burgaleta said. This new evangelism calls “for the church to go out of itself and engage in a new evangelization that was especially attentive to the peripheries of our world,” which echoes what the pope proposes in Evangelii Gaudium.

For details, visit the GRE website or contact Lauren Manzino.

]]>

The Catholic Church has had a complicated relationship with liberation theology, said Associate Professor of Theology Michael Lee, Ph.D. On the one hand, the movement’s emphasis on economic and social justice for the poor squares with Jesus’ message in the Gospels. On the other hand, its rumored connections to communism and the occasional violent outburst made the Vatican wary.

The Catholic Church has had a complicated relationship with liberation theology, said Associate Professor of Theology Michael Lee, Ph.D. On the one hand, the movement’s emphasis on economic and social justice for the poor squares with Jesus’ message in the Gospels. On the other hand, its rumored connections to communism and the occasional violent outburst made the Vatican wary.

However, through actions such as sanctioning Archbishop Romero’s beatification, Pope Francis is demonstrating that the Church ought to draw on the Gospels to find a middle ground within even the most controversial issues.

Watch Inside Fordham’s interview with Lee on the pope’s attitude toward liberation theology and its impact on the Church.

]]>