Especially regarding the LGBTQ community, the Orthodox Church has consistently become “hung up on the division between Orthodox and un-Orthodox, the division between holy and unholy, taboo and sacred,” said Ashley Purpura, Ph.D., GSAS ’14, associate professor at Purdue University and visiting associate professor at Harvard Divinity School. “But there is a way that love is transcending [this divide].”

She spoke at “Seeking Harmony and Compassion: Helping Parishes with LGBTQ+ Ministry,” a discussion organized by Fordham’s Orthodox Christian Studies Center at the Lincoln Center campus. She was joined in conversation by Cristina Traina, Ph.D., Avery Cardinal Dulles Chair of Catholic Theology at Fordham.

“There is an urgency to the matter because [our churches] are turning people away who don’t feel they have a home,” said Traina.

Orthodox Christianity in the Modern World

Purpura noted that some portions of the Orthodox Church, notably the Moscow Patriarchate, have presented the LGBTQ community and pride parades as a part of a larger threat by the West to the church’s traditional values.

But others see a question of how the Orthodox Church lives out the Christian faith in the modern world. A growing number of clergy, laypeople, and academics—including Purpura—are offering a pastorally and theologically grounded response to ministering to LGBTQ Orthodox faithful.

Purpura studies how Orthodox Christian thought and practice in the Byzantine tradition haves shaped power structures, identities, and conceptions of gender. She was co-editor of Orthodox Tradition and Human Sexuality (Fordham University Press, 2022), which has a companion study guide.

Acceptance of the LGBTQ Faithful

During the talk, she touched on a number of ways that the Orthodox tradition can be a resource for acceptance of the LGBTQ faithful. For instance, gender binaries have been transgressed in the Orthodox tradition, she said, mentioning the case of Matrona of Perge, an Orthodox Christian female saint who lived for a time as a male monk.

Purpura also invoked the Orthodox tradition and, more broadly, Greek philosophy’s conceptions of love—including eros, or passionate love and desire, and agape, or selfless love for God and others.

In relationships filled with both, she said, “If we really see love—no matter what form it is taking—bearing fruit and already transfiguring that couple or those individuals, then I don’t understand how we can say that … this is not theotic,” transforming and advancing one’s relationship with God, or that “the presence of God [is not]in this union.”

She expanded this picture to include the entire church and all humanity, saying that divine-human communion “happens as a community” and in relationships. “It is not just an individual enterprise.”

‘Love Christ in Your Neighbor’

Thus, Purpura insisted that the Orthodox Church can no longer say the LGBTQ community does not intersect with the church’s past and present. Instead, all Christian communities are called to embrace all people through their capacity “to see Christ and love Christ in your neighbor.”

While maintaining the tradition as necessary and vital for the life of the Orthodox Church, Purpura emphasized that “what is most central, is our relationship with God, our experience of God’s love and communicating that love to others.”

“We cannot say we are loving God and then be cruel to the people who we encounter in our lives,” she said. “If you are not letting that love transform you and your relationships, then I do not know what Orthodoxy is.”

Orthodox Tradition and Human Sexuality resulted from a trailblazing project sponsored by the Oslo Coalition on Freedom of Religion or Belief that brought Orthodox clergy, academics, and laity together to engage in collective study and discussion.

— Harry Parks, Fordham College at Rose Hill, Class of 2024

]]>Disorderly Men: A Novel

In Disorderly Men, Fordham English professor Edward Cahill evokes New York City in the mid-20th century, several years before the 1969 Stonewall uprising catalyzed the movement for LGBTQ+ rights. The novel opens with a police raid on Caesar’s, a mob-owned gay bar in Greenwich Village, where Roger Moorehouse, a Wall Street banker and World War II veteran with a wife and children in Westchester, was about to leave with “the best-looking boy” in the place. “Fragments of his very good life—the fancy new office overlooking lower Broadway, the house in Beechmont Woods, Corrine and the children—all presented themselves to his imagination as fitting sacrifices to the selfish pursuit of pleasure,” Cahill writes.

In Disorderly Men, Fordham English professor Edward Cahill evokes New York City in the mid-20th century, several years before the 1969 Stonewall uprising catalyzed the movement for LGBTQ+ rights. The novel opens with a police raid on Caesar’s, a mob-owned gay bar in Greenwich Village, where Roger Moorehouse, a Wall Street banker and World War II veteran with a wife and children in Westchester, was about to leave with “the best-looking boy” in the place. “Fragments of his very good life—the fancy new office overlooking lower Broadway, the house in Beechmont Woods, Corrine and the children—all presented themselves to his imagination as fitting sacrifices to the selfish pursuit of pleasure,” Cahill writes.

Also caught up in the raid are Columbia University professor Julian Prince and his boyfriend, Gus, a “serious-minded painter” from Wisconsin who gets knocked unconscious by a police baton; and Danny Duffy, a Bronx kid who helps manage the produce department at Sloan’s Supermarket. They’re charged with “disorderly behavior,” and their lives are upended—Roger is threatened by a blackmailer, Danny loses his job and family and seeks revenge, and Julian searches for Gus, who goes missing.

Cahill depicts their crises with pathos, humor, and suspense. And like the best historical fiction, Disorderly Men not only evokes a bygone era but also feels especially vital today.

Midnight Rambles: H. P. Lovecraft in Gotham

The cult writer H. P. Lovecraft was not well known during his lifetime, most of which he spent in his native Providence, Rhode Island. But the so-called weird fiction he wrote in the 1920s and 1930s—a blend of horror, science fiction, and myth—has “entranced readers” and influenced artists in various media ever since, David J. Goodwin writes in Midnight Rambles.

The cult writer H. P. Lovecraft was not well known during his lifetime, most of which he spent in his native Providence, Rhode Island. But the so-called weird fiction he wrote in the 1920s and 1930s—a blend of horror, science fiction, and myth—has “entranced readers” and influenced artists in various media ever since, David J. Goodwin writes in Midnight Rambles.

From shows like Netflix’s Stranger Things to the films of Academy Award-winning director Guillermo del Toro to the novels of Stephen King and beyond, artists have been inspired by Lovecraft’s “vivid world-building and bleak cosmogony.” They’ve also been repulsed by his racist and xenophobic views.

Goodwin, the assistant director of Fordham’s Center on Religion and Culture, deals with this head-on in Midnight Rambles, a chronicle of the writer’s love-hate relationship with New York and the city’s effect on him and his writing. He describes the brief period—from 1924 to 1926—when Lovecraft lived in Brooklyn, drawn there by Sonia Greene, a Ukrainian Jewish émigré he met at a literary convention in Boston. Their marriage soon fell apart, and he moved back to Providence, where he died in 1937 at age 46. “An extended encounter with a great city reveals and exaggerates the strengths, foibles, attributes, and flaws of a character in a film or a person in the flesh-and-blood world,” Goodwin writes. “This is certainly true of Lovecraft and his years in New York City.”

]]>“It became very clear to me, very quickly, that women were not being very well treated,” she told PBS in 2013, adding that “what started as a career really was going to be a mission.”

“I think we can be the generation that solves breast cancer, and that’s what drives me,” she said.

It drove her to co-author Dr. Susan Love’s Breast Book, initially published in 1990 and often called the bible for women with breast cancer, and to lead the National Breast Cancer Coalition and the Dr. Susan Love Foundation for Breast Cancer Research. Next month, the seventh edition of her book will be published.

The publication comes about four months after the game-changing surgeon, who was also an advocate for LGBTQ+ rights, died of recurrent leukemia on July 2 in Los Angeles. She was 75 years old.

A Unique Perspective

Born in Long Branch, New Jersey, in 1948, Love attended college in Maryland for two years and considered becoming a nun. She entered the convent of the School Sisters of Notre Dame in New York City but left after a few months and enrolled at Thomas More College, Fordham’s undergraduate school for women from 1964 to 1974. She earned a bachelor’s degree from Fordham in 1970 and went on to earn an M.D. from the State University of New York Downstate Medical School.

Love completed her surgical residency at the former Beth Israel Hospital in Boston, but her early career was affected by blatant sexism. “I finished, and I was chief resident, and then nobody offered me a job,” she told UCLA in 2018. “Usually, when you’re a chief resident at one of the Harvard hospitals, you get heavily recruited. Nobody wanted a woman.”

Whether they wanted her or not, she was there to stay. In 1980, she became the first woman general surgeon on staff at Beth Israel, and though she initially resisted becoming a breast surgeon, she determined that she could “make a much bigger difference” by helping women with breast issues than she would by specializing in any other area, she said. She believed that “there’s always something unique that … you can bring to the table.”

It was at Beth Israel Hospital that she met a fellow surgeon, Dr. Helen Cooksey, who would become her lifelong partner. They married in San Francisco in 2004 and, in all, were together for more than 40 years.

Not only did she co-found the Boston-based Faulkner Breast Center in the late ‘80s, but she also joined what is now the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and helped establish the Revlon/UCLA Breast Center.

After retiring as a surgeon in 1996, she earned an M.B.A. from UCLA. She joined the Santa Barbara Breast Cancer Institute, later renamed the Dr. Susan Love Foundation for Breast Cancer Research, and helped launch the Love Research Army, which recruits volunteers to participate in clinical trials and cancer research.

Paving the Way for LGBTQ+ Families

In addition to tirelessly advocating for breast cancer care and research, Love’s personal journey to motherhood made her a pioneer in the fight for LGBTQ+ couples to create biological families. With the help of a sperm donation from Cooksey’s cousin, the couple conceived a daughter, whom Love carried. They eventually helped to legalize same-sex families when they successfully sued the state of Massachusetts in 1993 to be permitted to list the names of both the birth and non-birthing mother on a child’s birth certificate.

“They use the term disruptor now for pretty much everybody,” said Christopher Clinton Conway, CEO of the Dr. Susan Love Foundation for Breast Cancer Research. “But Susan was the original disruptor.”

She is survived by her wife, daughter, two sisters, and a brother.

]]>Re: Our Pride and Joy

Last weekend, for the second year in a row, Fordham hosted the Outreach Conference on Catholic Ministry and the LGBTQ community. With welcome letters from Pope Francis and Cardinal Dolan, the conference created (as the pope described in his handwritten note) a beautiful “culture of encounter.” Outreach followed Fordham’s own impressive Ignatian Q conference.

During this Pride Month, I want to say directly to our own LGBTQ community of students, faculty, administrators, and staff that you are loved by Fordham and by the fellow members of the Fordham community. Most of all, I want you to know in your core that you are bathed in God’s overwhelming love and acceptance.

We are in awe of your courage. As a deep part of our mission, we will work ever harder to make you feel respected, welcome, and safe.

All my best,

Tania Tetlow

President

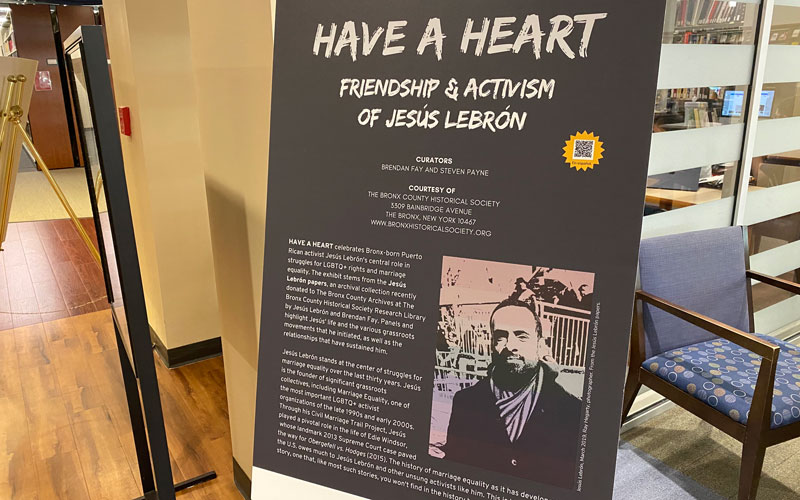

His story is now on display at Quinn Library at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus in a new exhibit “Have a Heart: Friendship and Activism of Jesùs Lebròn.” Lebròn donated his papers, artifacts, and more to the Bronx County Historical Society Research Library, where the exhibit was first displayed. It was curated by his friend and fellow activist Brendan Fay, as well as Steven Payne, director of the Bronx County Historical Society, who received his Ph.D. at Fordham in 2019.

Professor Karina Hogan, who helped bring the exhibit to Fordham, saw it first at Bronx Community College and said seeing it and speaking to Lebròn and Fay afterwards had a huge impact on her and the development of her Religion in NYC course.

“It was transformative for me,” she said. “I thought, ‘Oh it would be so cool to try to get the exhibit here because it’s so related to what I was teaching in my class.’”

Fighting Against the Defense of Marriage Act

The exhibit tells the story of Lebròn, who was born in the South Bronx, and how his work impacted LGBTQ rights in the U.S. In 1985, he became the manager of the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in Greenwich Village in Manhattan, which was the first to sell LGBTQ-themed books. It was there that he met Fay, who became a friend and fellow activist in fighting for LGBTQ+ rights.

Lebròn got involved locally, starting Gay & Lesbian Advocates for Change, the first group in New York to ask political candidates about their stance on gay marriage. Following the passage of the Defense of Marriage Act in 1996, Lebròn co-founded an organization called Marriage Equality, which grew to more than 40,000 members across various states, and organized educational and political campaigns. He led all of these efforts despite being diagnosed in 1991 with AIDS, which he’s lived with ever since.

The Civil Marriage Trail

In 2003, Lebròn and Fay started the Civil Marriage Trail Project, which helped LGBTQ couples travel to Canada—and eventually Massachusetts and Connecticut—to marry where it was legal. One of the couples who used the trail was Edie Windsor and Thea Spyer. After Spyer died in 2009, Windsor’s legal efforts for her wife’s estate traveled to the Supreme Court, which ruled in her favor in United States v. Windsor in 2013. That case laid the groundwork for Obergefell v. Hodges two years later which legalized marriage equality.

Local History, National Impact

Hogan said that she hopes the exhibit will help students and community members understand the connections between local history and national impact.

“We owe a lot to these two guys, especially to Jesùs Lebròn, who was this kid who came up out of poverty in the South Bronx,” she said. “They had such a huge impact on American history and nobody even knows about it.”

The exhibit was opened at the Ignatian Q conference and will be on display at the library through the end of June.

]]>

It was an event that fostered connection and hope—and moved some student to tears. On the weekend of April 21 to 23, students from 14 Jesuit colleges and universities came to Fordham for Ignatian Q, a conference emphasizing community, spirituality, and ways of achieving full inclusion and belonging for LGBTQ+ students on their campuses. The conference has been hosted at various schools in the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities (AJCU) since it was founded at Fordham in 2014.

It was an event that fostered connection and hope—and moved some student to tears. On the weekend of April 21 to 23, students from 14 Jesuit colleges and universities came to Fordham for Ignatian Q, a conference emphasizing community, spirituality, and ways of achieving full inclusion and belonging for LGBTQ+ students on their campuses. The conference has been hosted at various schools in the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities (AJCU) since it was founded at Fordham in 2014.

The messages conveyed during keynote speeches, breakout sessions, a Mass, and other events made for a conference that was, in the words of one organizer, “amazing.”

“I don’t even know how to describe it. Everyone was crying. It was more than I could have ever hoped for,” said Ben Reilly, a senior at Fordham College at Rose Hill and chair of the Ignatian Q Planning Committee. “It seems to have breathed life into the conversation around LGBT life on campus and LGBT student community, and the importance of community both at Fordham and across our AJCU family.”

Speakers were unsparing in describing the obstacles to LGBTQ+ equality. The weekend began with a keynote at the Church of St. Paul the Apostle, next to the Lincoln Center campus, by Bryan Massingale, S.T.D., a gay Catholic priest and the James and Nancy Buckman Chair in Applied Christian Ethics at Fordham.

He spoke of the necessity of dreaming as a step toward creating a just society in which people no longer face intolerance and violence because of gender identity or gender expression.

“That dream is under attack—blatant attack, disturbing attack,” he said, citing laws against “life-saving, gender-affirming medical care” and discussion of LGBTQ topics in schools, among other things. “There are serious efforts underway,” he said, “to create a world in which we don’t exist.”

He decried the idea that “God does not love us and we are not worthy,” saying “we have to dream of a world and a church where that lie is put to rest.” During his address, he prompted everyone in the pews to turn to one another and give affirmations including “you are loved” and “you are sacred.”

Visibility, Understanding, Acceptance

Saturday’s keynote was delivered at the Rose Hill campus by Joan Garry, FCRH ’79, a nationally recognized LGBTQ activist and former executive director of the gay rights organization GLAAD.

“The LGBTQ movement for equality needs all of you—badly,” said Garry, who serves on the executive committee of the President’s Council at Fordham. She urged the students to be activists who foster greater inclusivity at their colleges and universities and provide a model for other LGBTQ students who may be struggling.

“Visibility drives understanding, and understanding drives acceptance,” she said. “When you are ‘out,’ you model authenticity and honesty, and you show people the way. We illustrate that one does not have to be controlled by the expectations of others, and do you know how big that is? That’s a superpower.”

The event was supported by Campus Ministry and the Office of Mission Integration and Ministry. Father Massingale celebrated Mass at the Lincoln Center campus on Sunday, and for some students, it was their first time attending Mass since coming out, Reilly said.

Also on Sunday, in a keynote at the Lincoln Center campus, James Martin, S.J., the prominent author and editor at large at America magazine, said the openness of more and more LGBTQ people in parishes and dioceses ensures that the Catholic Church will continue to become more open to them.

“As more and more people are coming out, more and more bishops have nieces and nephews who are openly gay. That just changes them,” he said. “And that’s not going to stop.”

]]>The group—a professor, a psychologist, and three students—gathered in a classroom in Duane Library on Feb. 14, where they spoke to members of the Fordham community about how love appears in their professional work.

Literature on Love

Some of them shared their favorite literature on love. Thomas O’Donnell, Ph.D., associate professor of English and medieval studies, printed out three poems and passed out copies to the audience: a joyful poem written by Comtessa de Dia, a 12th-century French noblewoman; a mournful poem by Umm Khalid, an Arabic poet from the 8th or 9th century; and a funny poem by Geoffrey Chaucer, a 14th-century English poet.

“[Chaucer] says he is so in love that he feels like a piece of roasted fish in jam sauce,” O’Donnell said, to laughter from the audience.

Asher Harris, a Ph.D. student in theology, talked about American jazz musician John Coltrane, who expressed love and gratitude to God for saving him from his heroin addiction. The most open expression of this love appeared in his album A Love Supreme, particularly in the song “Psalm,” said Harris, who played a recording for the audience.

Another scholar, Christopher Supplee, FCRH ’25, a creative writing major, shared a poem he wrote and recited in honor of the event: “A World Without Love.”

“There are matters that cannot be mended by mortal hands alone,” he said to the audience, reading from his poem. “That only miracles may fix, assuming they still exist.”

Supplee said that when he was writing his poem, he was inspired by the question “What is love?”

“It made me want to sit down and think about what love means to me—what are my experiences, what I’ve read, what I’ve been taught from scholars, writers, and entertainment,” Supplee said. “Love can be expressed in many different ways, whether it be through justice, romance, or friendship.”

Queer Love at Fordham

Other scholars shared their own research on love. Benedict Reilly, a senior at Fordham College at Rose Hill who studies theology, discussed the theme of love from his book Queer Prayer at Fordham. He started the book project two years ago, interviewing LGBTQ+ members of the Fordham community about how they pray. During those conversations, he learned about the connection between prayer and love. One interviewee said that she learned to love herself through prayer. Another interviewee—an asexual and aromantic woman who longed to have a child of her own—spoke about how she found love and comfort through a Hail Mary.

“I’m sharing all of these with you because I want you to think about different prayers or songs that might be helpful to you all as you fall in love,” Reilly said.

The final invited speaker, Sarika Persaud, Ph.D., a supervising psychologist in Counseling and Psychological Services who specializes in love and relationships, spoke about what her work has taught her about love.

“When I’m sitting with a person and helping them heal, I’m not only opening them up to love as a feeling, to feel love again, but to love as who you are—to exist in the world as love,” said Persaud, who added that her Hinduism philosophy informs her work. “All of your desires, whatever relationships you enter into, whatever relationships come your way, whatever challenges come your way, they’re all opportunities … to love more.”

What Love Means to a Jesuit

After each guest spoke, event host and theology professor Brenna Moore invited the audience to reflect on what love means to them.

Among them was Timothy Perron, S.J., a Jesuit in formation and doctoral student in theology.

“As somebody who has taken a vow of celibacy, a lot of times, people think, ‘What could that person know about love, especially romantic love?’” Perron said. “But actually, I’ve thought about it a lot.”

Before he decided to become a priest, he wondered if he could commit to that vow. After much thought, he said he realized that every human has the same needs and desires, but they appear in different ways.

“I still have a need for close friendship, intimacy, love, and care for others … [but there are]all of these different ways that love could be understood,” Perron said. “If I see somebody who is looking for money or something, I’ll often stop and talk to them or take them to the nearest deli … Just stuff like that, where you feel that love and that connection … intentionally developing close relationships with people, keeping in close touch, calling them—all of those sorts of things, I think, are part of what love means.”

]]>

Dozens of senior students celebrated at Diversity Graduation ceremonies in early May, toasting to their accomplishments while honoring their culture and identity.

Dozens of senior students celebrated at Diversity Graduation ceremonies in early May, toasting to their accomplishments while honoring their culture and identity.

The celebrations took place from May 2–6 at the Rose Hill and Lincoln Center campuses, honoring students from the Black, Latinx, LGBTQ, and Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities. Seniors received colored stoles, certificates, and other items that symbolized their identity.

Juan Carlos Matos, assistant vice president for student affairs for diversity and inclusion, said the events drew a lot of excitement this year, with students buzzing about the celebrations beforehand and younger classmates leading the planning process.

“I think being able to create a tradition that folks look forward to and a culminating experience that connects back to people’s identity and culture is an important thing for the Fordham community,” he said.

Dorothy Bogen is a Fordham College of Rose Hill sophomore who served as a programming coordinator for the LGBTQ History Month committee of the Office of Multicultural Affairs, which ran the Diversity Graduations.

In her role she also led the planning for other events, including the Lavender graduation ceremony for LGBTQ seniors, which featured an appearance from theology Professor Patrick Hornbeck, Ph.D.

“Professor Hornbeck gave an inspiring speech (even with a fire drill interruption!) and it was awesome to feel the joy and the energy in the room as students were called up to receive their stoles,” said Bogen, an American Studies and Film and Television major from Cleveland. “We also got to connect with the Rainbow Rams (the alumni group for Fordham LGBTQ graduates), and their representatives also gave great speeches on both campuses.”

Arianna Chen, a Fordham College at Rose Hill senior from Wayne, New Jersey, attended the AAPI ceremony. She said she was grateful that the Office of Multicultural Affairs hosted these events and took the time to “acknowledge and celebrate the unique experiences held by students of varying identities.”

“It was important for me to participate in the Diversity Graduation ceremony because my identity has been a key part of my Fordham experience, not only as a DEI student activist, but also just a student of color navigating a predominantly white institution,” she said.

Chen received an AAPI stole and ACE (Asian Cultural Exchange) pin that she said she is “so looking forward to proudly donning at [her]Commencement ceremony.”

Matos said there was a “mix of support, love, and joy” at the events, each of which featured a recorded greeting from Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham.

“Students being able to celebrate with their peers and be celebrated was a huge deal,” he said.

]]>“The whole concept of sexuality was confusing. I chose to repress the subject rather than confront it,” he wrote in a memoir that he completed in 2017, the year before he died.

As he worked to overcome fear and secrecy about his own homosexuality, he wanted to help others do the same. This intention fueled his desire to write his memoir, not yet published. And it motivated him, in one of the final acts of his life, to make a gift to advance the cause of inclusivity and tolerance across all lines of difference.

With a bequest of $200,000, Esposito created the first endowment for Fordham’s Office of Multicultural Affairs, a fund that is now poised to bear fruit for the office’s programming. The funding arrives, in fact, in the midst of a Fordham fundraising campaign, Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, that has diversity, equity, and inclusion at its heart.

“He would be so proud to be part of this campaign,” said Jackie Comesanas, senior director of gift planning in Development and University Relations at Fordham, who worked with Esposito on setting up his gift. Esposito wanted to make a diversity-related gift focused on the Bronx and Fordham, of which he had fond memories, she said.

In the Struggle

A Brooklyn native, Esposito worked in hotels and catering during his time at Fordham and went on to become a hotel casino executive and entrepreneur.

He served as vice president of sales for Fairmont Hotels, vice president of MGM Reno, and president of Bally’s Las Vegas, among many other roles. In 1988, he founded the successful sales and marketing consultancy Hotel Management International.

He was a driven executive, at times “over the top” in motivating his staff, he wrote in his memoir, My Name is Joe: The Journey of a Gay Recovering Alcoholic in the Casino Industry.

He was also a talented salesman whose strength was his authenticity, said Robert Benz, a longtime friend and former business partner of Esposito’s. “Being real and being himself was what made him a great salesman,” he said.

But Esposito also felt shame at not being more forthright about his sexuality. Was He gained clarity about his sexual orientation in his early 20s but still “compartmentalized” it and avoided the topic, he wrote in his memoir. He wrote of spending time with three nephews during their youth and young adulthood, traveling around the U.S. and Europe, but never discussing his sexuality with them until he had reached middle age.

“Here I was, now in my early forties, telling these guys in their twenties that I was gay,” he wrote.

One of them responded by saying “‘How could you spend so much time with me and hide who you are?’ I gave the standard answer that, “‘Being gay is not who I am,’” he wrote. And—“I asked him why he did not tell me that he was straight.” (Later on, he said, “it was fun being his gay uncle.”)

Esposito said he met many heterosexual people who stood up to anti-gay bigotry. But hate reared its head often. There was a day in 1980, at the MGM Reno, when his secretary came back from lunch and seemed to be hiding herself a bit. He walked around her desk and saw a red mark on her face.

“I do not know to this day how I knew that Maria had defended me,” he wrote. He responded with some gentle humor, telling her they couldn’t get into a fight with everyone that called him a name—“If we did, then we would both be fighting a lot with our 2,500 employees and neither one of us would get any work done.”

In 1984, he co-chaired the Las Vegas Task Force on AIDS with then-governor Grant Sawyer. The AIDS epidemic claimed the life of one of Esposito’s best friends, someone whose family hadn’t known he was gay. At a gathering following the funeral, Esposito wrote, “the gay people were on one side of the room, the family on the other, and a giant division in between,” as the family reeled from both the loss of their son and what they hadn’t known about him.

“My generation often kept our private lives hidden from family. It was wrong for us to do whether they accepted us or not,” he wrote. “It took away from our personal dignity.”

Esposito did his part to help people shed secrecy and fear about their orientation, said his husband, Edgar Esposito, whom he wed in Las Vegas in 2015.

“He was a person who wanted everybody to be happy, and just help as much as he could to make sure that those who are gay and in the closet a little bit make their way out in a much easier way,” Edgar said. “One of his nephews has a gay son, and the nephew came to him to talk about his son, and he kind of helped the nephew understand that acceptance is a very powerful thing, especially when it comes to your child.”

Alcoholics Anonymous

Sobriety, supported by the spiritual aspect of Alcoholics Anonymous, was an anchor of Esposito’s life. He turned to AA at age 30 to deal with “blackout” drinking rooted in childhood fears, inner emptiness, and the stresses related to being gay in a world that was not always tolerant. “Many people in my generation were fearful” about their sexual orientation, he wrote.

When he walked into his first AA meeting, “it was like I met people from my planet for the first time.”

Forty-six years of sobriety, he wrote, “is the most important accomplishment of my life.”

Esposito struggled with cancer toward the end of his life; he died on March 4, 2018, at the age of 76, within a year of signing the agreement to create an endowment at Fordham.

Impact of the Endowment

The Joseph E. Esposito Jr., FCRH ’63, Endowed Fund will help the Office of Multicultural Affairs expand its various efforts to foster cross-cultural competencies, engagement of diverse students, and a more welcoming and inclusive atmosphere, said Juan Carlos Matos, assistant vice president for student affairs for diversity and inclusion.

“Now we can reimagine things in ways that we couldn’t before,” Matos said. He plans to manage the funding for the greatest possible long-term impact. “I feel like there’s an obligation to make sure we’re spending any funds in an intentional way,” he said.

The endowment could help send students to diversity-related conferences or bring speakers to campus, for instance; it could also give the office’s student-run cultural committees latitude to come up with more on-campus programs and events.

With more events comes more student involvement, in a kind of “domino effect,” Matos said.

“Once you’re able to do some larger-scale programs that have an impact … you’ll naturally then have more students that are aware of either what the office does or ways to get connected, and then those students then join the committees and want to continue doing that work.”

The endowment could be used to sustain one-time events that drew a strong response from students, like the block party held at the Rose Hill campus during Welcome Week this past fall or the diversity graduation celebrations held last spring.

The celebrations for Black, Latinx, and LGBTQ students and students of Asian or Pacific Islander descent were held in conjunction with the Office of the Chief Diversity Officer, using funds that been freed up by the scaling down of in-person events during the pandemic lockdown of 2020-2021, Matos said.

The Esposito fund “allows us a level of sustainability for these really important events that we hope become markers of students’ experience here at Fordham,” he said. “The more you’re able to provide these experiences … that people look forward to, that increases a sense of belonging.”

Learn more about Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student and make a gift.

If you have a question about giving to Fordham, call 212-636-6550 or send an email to [email protected].

]]>“We want to affirm to all our students that they are loved, and they are recognized for who they authentically are,” said John Gownley, assistant director of church operations and special events.

While the retreat, which runs from Nov. 12 to 14, qualifies as a special event, Gownley noted that Campus Ministry regularly provides resources for LGBTQ students to deepen their spirituality on campus as they navigate their identity and sexuality.

But the retreat, known as the Prism Retreat, is decidedly off campus, said Chloe McGovern, a senior at Lincoln Center and the student director for the event.

“We’ll leave together from the McGinley Center and our Ram Van drivers are also retreat leaders, so they’ll pick the music, and we’ll have a jam session on the way there,” said McGovern.

McGovern declined to provide an itinerary of the trip, noting that the whole point was for students to put their phones down and let the weekend unfold before them. She said the retreat leaders will take care of the cooking and run the activities. There will also be time set aside for students to be alone and take in the natural surroundings.

“We’re creating a safe space where queer identity and spirituality come together, and you can hold those two identities together,” she said. “It’s not strictly religious, but we’ll offer times to connect spiritually through meditation, queer-friendly prayers, and through sharing.”

McGovern said that in the past the Prism retreat helped students struggling with self-acceptance and self-love, but this retreat will focus more on happiness and positive experiences of being true to oneself.

“We’ve had discussions dedicated to negative queer experiences, and we’ll still deal with that, but we’re just saying that the way we want to lead this retreat is to focus on positive ways that LGBTQ people are living their lives and on queer joy.”

McGovern said that for some the retreat will culminate upon return to campus when the vans arrive in time for 5:00 p.m. Mass at the University Church. But she underscored that the spiritual aspect of the retreat is open to students of all faiths and spiritual expressions.

“A lot of our retreat leaders often lead a prayer by saying, ‘Please approach the divine in any way you see fit. I’ll be approaching the divine through my own faith background and how I’m comfortable; I hope you will too.’”

Students interested in attending the retreat have until November 11 to register.

]]>“I think one of the reasons you’re here is to make the world a better place than the one you arrived to,” she said. “And philanthropy is an incredibly powerful tool for that. I want the women at the Women’s Summit to own that. I want them to see that. I want them to evangelize that.” (Update: Watch Garry’s address at the Summit.)

Making the World a Better Place

For Garry, the desire to make the world a better place stems, in part, from her personal life. In the early 1990s, two decades before the Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges legalized same-sex marriage, she and her partner, Eileen, were discussing the next steps for their family.

“I believed really deeply that if we were going to have a family that it was incumbent upon us to do what we could to make the world as safe as possible for them,” she said.

They became plaintiffs in a precedent-setting case in New Jersey in 1993, and Garry eventually became the first woman in the state to legally adopt her partner’s biological children.

“It was a huge ‘aha moment’ for me, recognizing, cheesy though it may sound, that one person can really make a difference,” she said on an episode of the Fordham Footsteps podcast last summer. “And it was huge news,” she added. “The story of our family was educating people about members of the LGBT community in a very different kind of way. In the early 1990s, gay families were not common at all, and I realized that the media had this incredible power and responsibility to tell these stories and really shape how the LGBT community was perceived and understood.”

At the time, Garry was an executive at Showtime Networks, but her family’s victory in court inspired her to take her career in a different direction a few years later. In 1997, she was named executive director of GLAAD, a national nonprofit organization that aims to “rewrite the script for LGBTQ acceptance” and tackle “tough issues to shape the narrative and provoke dialogue that leads to cultural change.”

“Because GLAAD focused on the media as an institution where we could change hearts and minds, the bridge from corporate media to the nonprofit sector was a no-brainer for me,” Garry said.

Garry said that when she started at GLAAD, there were “precious few images at all” of LGBTQ people in the media, and when they were featured, the depictions were usually negative. She built partnerships with media executives to change that, working with the producers of Survivor to help get a gay man on the popular TV show in 2000 and successfully lobbying The New York Times to feature gay and lesbian couples in its “Vows” section.

“We are part of the fabric of society,” she said. “The object of the work was to ensure that the media representation reflected the diversity of our society that included LGBTQ members.”

Lessons Learned

Garry said her work at GLAAD was influenced by her previous jobs, particularly at MTV, where she began her career soon after graduating from Fordham College at Rose Hill with a degree in philosophy and communications.

At MTV, Garry learned the “dynamics, energy, and the urgency of a startup,” which became valuable to her as she transitioned to leading GLAAD.

“Running a nonprofit organization, they have a very similar energy [to a startup]—moving quickly, often too quickly, under-resourced,” she said. “The other piece that corporate America provided me was an understanding that numbers tell a story.”

And even before MTV, while still a student at Fordham, Garry said she learned about the value of having a mentor.

She got her start at MTV, several months before the network launched in 1981, thanks in part to her mentor James N. Loughran, S.J., FCRH ’64, GSAS ’75, a Fordham philosophy professor who later served as dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill. Father Loughran encouraged her to reach out to a Fordham graduate who was looking to build a team for a new project at Warner Communications.

“All I know is that one moment I was unemployed, and the next moment I was sharing an office with someone and looking at the Christmas tree at Rockefeller Center, and feeling like I had won the lottery,” she said with a laugh. “Little did I know that we were creating the business plan for what would become MTV.”

The ‘Accidental’ Consultant

All of those lessons helped prepare Garry for another career transition—starting her own consulting firm for nonprofits.

After working at GLAAD for eight years, Garry decided to focus more on helping raise her three children, who were in middle and high school at the time.

“We believe that older kids need you even more than younger kids,” she said with a laugh. “And so I went home to be on the ground when they got home from school.”

She began to take on some jobs as a way to “maintain my sanity,” Garry said, adding that she became an “accidental” consultant. In 2012, she launched a website to share tips, advice, insights, and lessons she learned from her time in the corporate and nonprofit worlds. The site “took off,” she said, and eventually led to a full-time consulting business and a book, Joan Garry’s Guide to Nonprofit Leadership: Because the World Is Counting on You (Wiley, 2017).

Garry said that she found that many nonprofit leaders don’t have advocates and supporters for their work, which is why she also launched the Nonprofit Leadership Lab to help provide support, networking, and professional development to leaders of nonprofits.

“These jobs—whether you’re running a food pantry or whether you’re researching the cure for a disease or you’re advocating for the Latinx community—these are hard jobs,” she said. “They’re really hard to get right and far too often these leaders do not have champions.”

Inviting People In

Garry said that one of the pieces of advice she plans to give those who attend the Summit, and one she often shares with nonprofit leaders, is to invite people in to be a part of their causes and work.

“It makes people feel good to give money to causes they care about—it is an invitation, an invitation to get closer to those things that drive meaning and purpose in your life,” she said. “And why wouldn’t you invite people to do that? They can always say no. But I’d like to be invited. And so I have grown to understand through all of the work that I have done raising money, that it is [about] offering someone the opportunity to bring meaning and purpose into their lives in a different way.”

In particular, Garry said that she wants to invite women to use philanthropy to support the causes they care about.

“Women have not been socialized in the same way as men to be philanthropic; they have had fewer opportunities,” she said. “And I would like them to leave feeling inspired to be engaged in philanthropy in whatever way it makes sense for them.”

Watch the Fifth Annual Fordham Women’s Summit. Garry’s keynote address begins at 3:44:20.

]]>