She was touring the country as a U.N. investigator, and it didn’t take long for the reality to emerge: Haitians were being forced into an undocumented, poverty-stricken underclass because of racial discrimination that was “quite alarming.”

“There was [a sense]that Haitians were not fully human beings,” said McDougall, Distinguished Scholar-in-Residence at Fordham Law School’s Leitner Center for International Law and Justice.

She describes this and other experiences in a new book, The First United Nations Mandate on Minority Issues (Brill Nijhoff, 2015), about her six years of investigating the oppression of minority communities worldwide.

McDougall served as first U.N. Independent Expert on Minority Issues, a job created in 2005 to help implement the U.N. General Assembly’s Declaration on the Rights of Persons belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities, adopted in 1992. She reported on the problems facing Macedonian and Pomak communities in Bulgaria, people of African descent in Colombia, the Roma in Bulgaria and Greece, and other minority groups during visits to 17 countries.

But her position was ill-defined from the start. Unlike the United Nations’ independent experts in other areas, McDougall had a limited job description that was silent on whether she could travel to countries and investigate complaints. So she interpreted this silence as permission, embarking on country visits that created a precedent for her successors while also strengthening and clarifying the language of the U.N. minority rights declaration.

“This is the whole point about documenting the first mandate, because the mandate became more than simply words on a piece of paper” during her tenure, she said.

The book describes her findings in various countries as well as some of the possibilities and challenges that come with the job. She met plenty of resistance—like the “diplomatic ‘no’” some countries gave when she asked to visit, or the obfuscation that was apparent in her interviews with government officials at all levels in the Dominican Republic.

“They said the exact same thing” in denying any problem with racism, McDougall said. But her other interviews showed institutionalized discrimination that kept Dominicans of Haitian descent from registering their children as citizens, shutting the children out of schooling and health care and, later in life, legitimate work.

“Since they don’t have the proper papers, they are ripe for exploitation in terms of their labor,” McDougall said, recalling one destitute Haitian community at the end of an unpaved road that struggled to survive on the income from seasonal work at area plantations.

“They have no electricity, they have no plumbing system, they have no school, they have no health system, they can’t get out of there,” McDougall said. “Some were born there, and many will die there without any kind of support. It was a very outrageous system.”

When she and a colleague presented their findings to a government minister in advance of a press conference, the minister “went berserk” with denunciations of their motives.

“I don’t think I went to any country where they were extremely happy about my findings,” McDougall said, unflappably.

Ideally, such findings can be used to bring international pressure or spur countries to address simmering problems within their borders. In another one of her trips, to the ghettos outside Paris, she found discrimination against minorities that kept them from getting even the relatively low-skilled jobs in the French gendarmerie, or police force.

The predictions in her report were borne out by the riots that occurred a few years later.

“Many told me they played by the rules, all the rules, and they are still rejected—for jobs, for basic services,” she said. “People will accept that kind of treatment only for so long.”

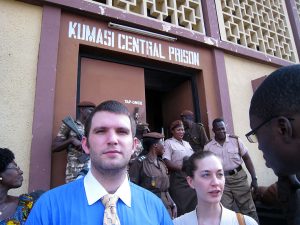

]]>He is serving as a pro bono consultant for the joint program developed by the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration and Ghana’s Mountcrest University College. The program is under review by Ghana’s National Accreditation Board.

With Fordham, Galizzi also runs several programs in Ghana, including a soon-to-be-launched clerkship for the judicial system that will be open to Fordham graduates. Through the Leitner Center he directs two clinics: Sustainable Development Legal Initiative (SDLI) and the International Law and Development in Africa (ILDA). He also directs the Law School’s Ghana summer program.

“I believe there is a significant market for Fordham and its graduates in Africa,” Galizzi said. “It is an often overlooked continent, too often known only for negative reasons. There is a lot that is positive happening in Ghana and I believe Fordham should be at the forefront of it.”

While there are good law doctoral programs elsewhere in Africa, there are none in Ghana, he said—even though most Ghanaian law schools require a PhD to teach, forcing candidates to emigrate. Besides the personal burden of requiring law students to leave their professional and personal relationships behind, their research also gets exported.

“The idea of having a local PhD insures that there is local research and local supervision to develop the expertise,” he said. “For example there is no way to study environmental law in Ghana right now. You can do it here in the United States, but that’s not going to help them.”

The country’s stability and technological innovations make Ghana a place to take advantage of now, he said. And the legal system in Ghana is as good on paper as in the United States, with a very strong constitution that provides for the separation of powers and guarantees human rights.

“The problem is the implementation of the laws, but that’s a challenge we face here as well,” he said.

He compared the overcrowding at Rikers Island caused by a backlog of unheard cases to problems in Ghanaian prisons.

“The backlog problem in the U.S. is clearly resource-constrained, but they’re nothing compared to the challenges in Ghana,” said Galizzi, where there are 3,000 to 5,000 cases awaiting trial, sometimes for up to 10 to 15 years.

Through ILDA, Galizzi and Fordham law students have intervened on behalf of prisoners in through the Access to Justice Project. Fordham students work with Ghanaian lawyers to help to reconstruct prisoners’ case files and work with the judicial system to get the cased heard and those with expired warrants released.

Galizzi acknowledged an increased interest in Africa’s development by several nations. However, efforts by schools like Fordham to get involved still have an edge.

“In the educational sphere, American universities have a terrific reputation,” he said. “That bears heavily on the types of relationships that African universities want to establish.”

He said that Americans should remember the scars of Africa’s colonial past.

“If you go in and say what is good and what is bad, you usually get rejection because they know the problems they have,” he said. “It’s more of an exchange to see how we can assist.”

“Rather than the idea of exporting values, I prefer to say we share common ideals that can enrich both of us.”

Among the changes we can expect a decade from now are shifts in the way laws govern issues related to national security.

The symposium, which is open to scholars, practitioners and the public, will highlight the backdrops of rural poverty and educational underdevelopment as barriers to inclusion and to education for persons with disabilities.

Global Rights and Local Challenges

November 15, 2013

1-8 p.m.

McNally Amphitheatre, Fordham School of Law

Speakers will include:

Shantha Rau Barriga, Disability Rights Program Director, Human Rights Watch

Madame Jeanne d’Arc Byaje, Deputy Permanent Representative of the Government of Rwanda to the United Nations

Musola Catherine Kaseketi, Founder/Filmmaker, Vilole Images Productions

Anne Kelsey, Staff Attorney, Disability Rights Advocates

Sophie Mitra, P.D., Associate Professor of Economics at Fordham

Richard Mukaga, Program Manager, Cheshire Services Uganda

Two panels will explore the disability and poverty nexus, wherein disability and poverty lead to and accentuate each other in a pernicious cycle. Panelists will use case studies from the United States and around the world to describe how rural environments and the need for overall educational development can hinder inclusive education for persons with disabilities.

A student photography exhibit will also illustrate the social and economic obstacles that define disability in Rwanda and internationally. A screening of the award-winning documentary In The Shadow of the Sun at the close of the symposium will further illuminate the social stigma that persons with disabilities face.

For more info visit http://www.leitnercenter.org/events/1113/ or e-mail David James Harvey at [email protected]

]]>

If the global community is going to get serious about tackling the threat of climate change, the United States needs to get on board, according to associate law professor Paolo Galizzi, Ph.D.

But for that to happen, the political alignment needs to change radically, Galizzi said on Oct. 13 in a lecture on the Lincoln Center campus.

Galizzi, the director of the Sustainable Development Legal Initiative (SDLI) at the Leitner Center for International Law and Justice at Fordham Law, appeared as part of a lecture series sponsored by the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs.

In his talk, “The International Legal Framework on Climate Change: Principles and Obligations,” Galizzi detailed the origins of the international community’s response to climate change—from the first framework treaty in 1992, which the United States signed, to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which it did not.

“The objective of the convention is not to stop climate change, because that is just not feasible. Climate change is going to happen. But what you can do is reduce its impact so that changes occur in a way that is manageable,” he said.

“If you stabilize greenhouse gasses at a certain level, that stabilization will allow the planet to cope much better with the changes that are inevitable.”

Three principles are at the core of the international philosophy to deal with climate change, he said:

• common but differentiated responsibilities;

• precaution; and

• sustainable development.

The first principle indicates that all countries have an obligation to change, but that not every nation bears the same amount of responsibility for the problem or has the same capability to respond.

“If you are Burundi, a very poor, land-locked country in Eastern Africa, where the GDP is less than a dollar a day for most people, how can you ask them to do anything to help solve this problem?” he said.

“In theory, this principle is about fairness, and who pays for problems that are global problems, but as you’ve probably seen these days, the idea of what is fair and who pays for what is not always easy to define.”

The second principle, precaution, draws the most opposition in the United States because the premise is that even if you are only 90 percent certain that human behavior is causing global climate change, you should act on it, because if you don’t, it may be too late to do anything by the time you are 100 percent certain.

“We know that it’s a problem, but nobody can tell you with certainty that the sea level will rise by one meter in New York City on Dec. 1, 2025,” Galizzi said. “What people can tell you is that it is very likely going to happen at a certain stage.”

The third principle, which focuses on sustainable development, is divisive between poor countries and rich ones because the former insist that they should not be forced to slow their attempts at creating better lives for their citizens.

“It’s a very difficult argument to counter,” Galizzi said. “How can you tell people who live on less than a dollar a day who don’t have energy, access to water or transportation, that they do not have the right to aspire to what we take for granted?”

Complicating matters further are countries such as China, India and Brazil, which might have been considered developing countries in 1997 when the Kyoto Protocol was passed, but are not anymore. Their emergence was a factor when the U.S. Senate balked at signing the protocol, which would have bound the United States to reductions in greenhouse gases.

“The Senate said, ‘What is the point of the United States reducing its emissions by 7 percent by 2012 when China is going to increase its emissions by 20 percent during that time?’

“What’s the point? It’s global problem, so it makes sense for us to work together,” Galizzi explained in answer to his own question.

Sorting out differences between countries is integral to solving the problem because—unlike issues such as gay marriage—global warming will affect everyone on the planet. Galizzi noted that hurricanes, typhoons floods and other forms of severe weather that are expected to increase in the coming years will not differentiate between those nations that cut back on carbon emissions and those that did not.

But before that can happen, everyone in the United States needs to agree that global warming is, indeed, happening. Although virtually no serious scientist will deny that the Earth’s climate is changing, Galizzi said that the number of skeptics is increasing even though the science is actually stronger than it was 10 years ago.

“Climate science is not easy to understand. For most people, it goes over their heads. But they understand the very easy message that their energy bill goes up because of it, and their taxes go up,” he said.

“If you go to 100 doctors and 98 say that you have a disease, and two tell you that this particular disease doesn’t exist, who are you going to trust? The 98, or the two?”

The divide is mostly partisan, as demonstrated by the group of leading Republican contenders for president. Only one believes climate change is a problem.

“That’s Jon Huntsman, who has about as much of a chance of being elected as me, Galizzi said jokingly.

“Right now we’re stuck until there’s a policy change in the United States,” Galizzi said. “The rest of the world is pushing forward, but the truth is that unless you have some of the major players, it’s going to be really hard to do something serious. These days, the U.S. is very much the elephant in the room that is not moving.”

]]>These and other topics will be the focus of a daylong Fordham Law School conference on Thursday, Feb. 24 at the Lincoln Center campus, “Civil Society and Legal Activism in China: The Public Health Challenge.” The event is free and sponsored by the Leitner Center for International Law and Justice.

The conference gets underway at 9:30 a.m. in the 12th Floor Lounge of the Lowenstein Center, and consists of four panels throughout the day: Civil Society in China, Regulation and Practice; Anti-Discrimination Efforts in China; Public Participation Toward a Responsive Health System and China; and China: The Response to HIV/AIDS.

Scholars and activists who will be speaking include Timothy Webster, senior fellow at the China Law Center, Yale University; Benjamin Liebman, professor of law and director of Center for Chinese Legal Studies at Columbia University; Scott Burris, professor of law, Temple University and associate director of the Center for Law and the Public’s Health; Wan Yanhai, director of Beijing’s Aizhixing Institute; and Sara L.M. Davis, executive director of Asia Catalyst.

For more information or to register, contact Joy Chia [email protected].

—Janet Sassi

]]>

Adopted in 1948, the declaration represents the first global expression of rights to which all human beings are entitled.

“Human rights are not negotiable,” said Archbishop Nicolas Girasoli, the Apostolic Nuncio to Zambia and Malawi on Nov. 9. “Nobody can think to limit someone to breathe or to move, simply because these gestures belong to humans. The same should happen with human rights; they are rooted in human nature.”

Archbishop Girasoli, a highly regarded scholar and diplomat, was the guest speaker at the fall Gannon Lecture, held on Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus.

The author of several studies and books on the rights of national minorities, the archbishop discussed a “compromise approach” to minority rights and globalization.

“To be ready for a compromise means to be ready to renounce something and also to receive less than is expected,” he said. “But because human rights are not negotiable, we may negotiate everything but human rights.

“So, dealing with human rights, we shall recover the ancient Greek and Latin meaning of the word compromise, which refers to the activity of an arbitrator who solves disputes,” he continued. “In this way, compromise is not an exercise where someone must be ready to give up something but a composition of different points of view, which turn out to be a solution when accepted by all involved parties.”

In an era of globalization, countries continually face the challenge of its people living together while respecting differences, Archbishop Girasoli said. To assist in this effort, he introduced a concept he called “unity through diversity.”

“This means that the memories and traditions of each group of people must continue to evolve side by side with the national identity of the hosting state,” he said. “If everybody has the right to be equal, then minority groups have an additional aspiration—they want to maintain their right to be different.”

Archbishop Girasoli also called for academic distinction of minority groups.

“Minority groups cannot be defined in a unilateral way because they are complex realities,” he said. The archbishop defined national minorities as those who become so by destiny, (for example, due to an International Treaty at the conclusion of a war), and cultural minorities who become so because of choice.

“We also need to mention the ethnic minorities, migrant workers, trans-frontiers cultural groups and new emerging cultures,” he said. “Equality means that no cultural group should apologize for its origins, families or communities, and it requires that others show respect for them, and change public attitudes and arrangements so that the heritage they represent is encouraged rather than ignored.

“Today, the question is, ‘Are we ready to recognize and sustain a multicultural society where different ethnic and cultural groups work in solidarity and with an autonomy that should be recognized?’ I do not think that in a global era we can say no,” he added.

After his talk, Archbishop Girasoli was given a crystal owl.

“The owl, which is on the crest of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS), represents wisdom, knowledge and understanding, and that’s what you shared with us tonight,” said Nancy A. Busch, PhD., dean of GSAS.

The Gannon Lecture, which is endowed by Fordham alumni, began 30 years ago to honor the memory of Robert I. Gannon, S.J., president of Fordham from 1936 to 1949.

“It was not easy to be the president of a university during the Depression and World War II, but Father Gannon was equal to the challenges he faced,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “When it came to Fordham, he found a place in dire straits and yet was able to get it to thrive during the Depression and blossom after the war.”

The lecture was sponsored by GSAS, the International Political Economy and Development program, the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs and the Leaner Center for International Law and Justice.

]]>The new International Law and Justice program offers lawyers the opportunity to gain an advanced understanding of human rights protection and promotion at the international, regional, and domestic levels, from the historical evolution of these movements to the forefront of cutting-edge scholarship and debate.

The degree is designed primarily for foreign lawyers who work in public interest, including high-level government attorneys, leaders of non-governmental organizations, and academics.

Students in the program will choose from a wide range of courses in consultation with the program’s faculty directors, Martin Flaherty and Tracy Higgins, both Leitner Family Professors of International Human Rights and co-directors of the Leitner Center for International Law and Justice at Fordham Law School.

The LL.M. program in International Law and Justice is affiliated with the Leitner Center for International Law and Justice, one of the foremost centers for human rights study and advocacy in the United States. The Leitner Center and Fordham will offer full-tuition scholarships and living stipends for the program to eligible students from developing countries, including scholarships to two graduates of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) Faculty of Law in Ghana. The living stipends are made possible by James Leitner ’82.

For information about enrolling in the program, contact the LL.M. office at (212) 636-6883 or visit the program’s

website.

Including this gift, the Leitners have given just more than $7 million in the last three years. They made a $3.1 million donation last February that established a second Leitner Family Chair in International Human Rights and funded a human rights clinic. The couple also made a $2 million gift in 2005 that established the first Leitner Family Chair.

The Leitner Center has been created to promote social justice by encouraging knowledge of, and respect for, international law and human rights standards.

The additional funding will be used to develop new initiatives, including a visiting scholars program, and to establish the Human Rights Colloquium, a lecture and discussion series that will feature leading scholars.

James Leitner is president of Falcon Management Corp., a New Jersey-based investment firm that he founded in 1991. Before founding Falcon Management, Leitner held senior-level posts at financial institutions, including chief dealer at Bank of America International, vice president for proprietary trading at Shearson Lehman and managing director at Bankers Trust.

He and his wife have been longtime supporters of the 10-year-old Joseph R. Crowley Program in International Human Rights at the Law School. The Crowley Program will now become part of the Leitner Center.

]]>

Photos by Bruce Gilbert

Fordham Law School’s efforts to promote social justice through international law and human rights are being strengthened and expanded thanks to a new center.

The Leitner Center for International Law and Justice will serve as an umbrella organization for existing law school initiatives, including the 10-year-old Joseph R. Crowley Program in International Human Rights, through which law students participate in human rights fact-finding missions. In addition, the annual James E. Tolan Human Rights Fellowship will be administered through the center.

It also will sponsor a range of new initiatives dealing with everything from human rights advocacy to facilitating collaboration among law students, scholars and human rights activists in the United States and abroad.

“The Leitner Center consolidates much of what we were already doing and also serves as a platform for expanding our work in a systematic way,” said Tracy Higgins, Leitner Family Professor of International Human Rights and co-director of the center.

Officially launched at a ceremony on Sept. 19 at the McNally Amphitheatre on the Lincoln Center campus, the center has established several projects, including the Walter Leitner International Human Rights Clinic, which is designed to train a new generation of human rights lawyers and to inspire practical, results-oriented human rights work throughout the world.

Additionally, the center is organizing a colloquium to begin in the spring of 2008, which will bring to Fordham leading scholars of international law and political theory from around the world.

“We have created a new human rights clinic, three new faculty-led initiatives and internships for students,” Higgins said. “We also intend to invite visiting scholars to be affiliated with the center. As an umbrella organization, the new center can help to manage, publicize, promote and fund raise around these various initiatives.”

The center’s new projects include:

• The Sustainable Development Legal Initiative, which serves as a focal point for activities in the fields of human rights and sustainable development.

• The International Law and the Constitution Initiative, which provides research and advocacy opportunities for Fordham law students.

• The Center for International Security and Humanitarian Law, which analyzes effective regimes for the legal regulation of armed conflicts.

In addition, the center awards a human rights prize each year to an activist who assisted the Crowley Program during the prior year’s fact-finding mission. The center selected the first recipient last fall: Daphne Gondwe, president of the Coalition of Women Living with HIV/AIDS in Malawi. She received $1,000 and was flown to New York City to meet with representatives from international nongovernmental organizations.

]]>