“I don’t want to leave Kyiv. I was born here. I love Kyiv. Kyiv is the most beautiful city in the world,” said Vitaly Chernoivanenko, Ph.D., a Ukrainian scholar who spoke at a Fordham virtual panel on March 17. “I’m not afraid of Putin and his military forces.”

The panel is part of a new Fordham initiative designed to help Ukrainians during the Russia-Ukraine war. Fordham’s Center for Jewish Studies is co-hosting a virtual lecture series that discusses how the current crisis is affecting academia and co-sponsoring a fellowship program for Ukrainian scholars. The center is collaborating with three organizations: the American Academy for Jewish Research, the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in Germany, and the Lviv Center for Urban History in Ukraine.

“With people in war zones and in exile from their homes and in need of basic supplies, it may not seem urgent to give attention to scholarship. Nevertheless, society also depends on those who create and preserve knowledge through their scholarship, work, and institutions devoted to research and culture,” said Magda Teter, Ph.D., Fordham’s Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies and a professor of history who is moderating the lecture series.

The first lecture featured two Ukrainian scholars: Chernoivanenko, a senior research fellow at the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine and president of the Ukrainian Association for Jewish Studies, and Sofia Dyak, Ph.D., a historian and director of the Lviv Center for Urban History. The panel was moderated by Teter and Iryna Klymenko, Ph.D., a European history scholar from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

‘We Don’t Think About the Office or Our Laptops. We Think About People’

Chernoivanenko reflected on how the past three weeks have affected his professional and personal life. As a scholar who specializes in Jewish studies, preserving the work of his predecessors and colleagues is important, he said, especially in Ukraine, where his scholarship was once banned under Soviet rule.

“It’s a miracle that for these 30 years since our independence was proclaimed in 1991, we have a very prospective field … All these scholars sincerely want to research Jewish heritage of Ukraine and Eastern Europe,” said Chernoivanenko, who established the first Ukrainian peer-reviewed journal in Jewish studies and the first master’s degree program in Jewish studies in Ukraine. “It’s very important to preserve this heritage, especially now during the war.”

Chernoivanenko said many of his colleagues are still in Ukraine, where they are doing what they can to help with the war effort.

“We don’t think about the office or our laptops. We think about people, our colleagues,” said Chernoivanenko, speaking from Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine.

Chernoivanenko said he has been assisting local defense forces and strangers in the streets, including the homeless population. He added that he is thankful for his colleagues across the world who invited him to flee Ukraine by taking scholarship positions in their schools, but he said he wanted to stay home and help. His father and mother, who are 74 and 73, respectively, aren’t fleeing either, he said.

“My parents are very brave,” he said. “They said no, never. We believe in our military forces.”

Protecting Heritage and New Priorities

Scholars in Ukraine and those who have fled the country both need support, said Teter and Klymenko. There are opportunities that can help scholars who live anywhere, like the new fellowship co-sponsored by Fordham’s Center for Jewish Studies and the American Academy for Jewish Research, said Teter, which consists of a $5,000 stipend, remote access to library resources, and networking with faculty members from both institutions. Klymenko added that her own university’s history department has been providing financial aid and refuge for displaced Ukrainian scholars in Germany. Most of the refugees are women with children and elderly parents, she said.

“These are people, mainly scholars, who are basically trying to save their children from being further traumatized,” said Klymenko, who is affiliated with the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in Germany.

The war has also changed people’s views on the preservation of heritage, said Dyak, director of a research institution in Lviv, Ukraine. Her colleagues have been wondering whether or not their artifacts should be wrapped, hidden, or moved. They have also accommodated their facilities to the realities of wartime, she said.

“We turned our conference room and cafe into shelters … We are discussing [playing]cartoons and classic films for kids, but not home movies because that would be very painful. The shelter is for people who lost their homes or probably can’t go back to their homes,” Dyak said.

A Silver Lining and Hope

There is a silver lining within the chaos of the current crisis, said Teter.

“It is terrible that a war had to happen, but it puts your voices out there and makes the world discover the amazing scholarship that is being produced in Ukraine and your centers and institutions,” Teter said, directly addressing the panelists.

It is unclear when Ukrainian scholars will continue their partnerships with Russian scholars and institutions, said Dyak. She added that the path to collaboration will require much introspection on Russia’s part.

“Cultural arrogance can lead to violence,” Dyak said. “I am hopeful that in the future, from our shared experiences, we will be able to revisit, in a new way, conversations that are painful and hard … Right now we probably are not able to pick up these conversations, but I do hope that these shared experiences will create a space of trust.”

The second lecture will be held this Thursday, March 24, at 10 a.m. EST. Watch a full recording of the first lecture below:

]]>“Barbara has quietly been a groundbreaking figure in the field of Catholic feminist ethics. In a non-flashy way, she has been ahead of the curve on so many issues since the 1980s,” said Christine Firer Hinze, Ph.D., chair and professor in the theology department. “This lectureship refracts much of the work that Barbara has done over the years and ensures that light will continue to shine on those issues, especially at Fordham.”

This past January, Andolsen made a bequest that will support an endowed fund for the Barbara Hilkert Andolsen Memorial Lectureship. Every year, Fordham’s theology department will host a prestigious scholar to speak on a topic related to economic, racial, or gender justice, with special attention given to marginalized racial and cultural groups. The endowed fund for the lectureship will soon be open to other contributions from the public.

Andolsen is a feminist theologian and ethics scholar. From 2008 to 2019, she held several positions at Fordham, including the first James and Nancy Buckman Chair in Applied Christian Ethics, associate director of the Center for Ethics Education, and professor of theology. Andolsen previously taught at Monmouth University, Rutgers University, and Harvard Divinity School. She earned her Ph.D. in religion from Vanderbilt University, with a specialization in Christian ethics.

Andolsen’s research was ahead of her time, said Hinze. In her book Daughters of Jefferson, Daughters of Bootblacks: Racism and American Feminism (Mercer University Press, 1986), Andolsen wrote about how the women’s rights movement in the U.S. could have been different if more attention had been given to Black feminist perspectives. Andolsen also wrote The New Job Contract: Economic Justice in an Age of Insecurity (Wipf and Stock, 2009), the “first feminist analysis to connect religious understandings of economic justice with the issues facing both workers and the wider community,” according to the book publisher.

“Much of her work has brought together economics, business, feminism, Catholic ethics, and social thought in distinctive ways that were really pushing the field forward. She drew attention to many issues—including racism in the women’s movement, caring for the frail elderly, technology, and job insecurity—that were on the cusp of what was happening in society and in ethics,” Hinze said.

In a phone interview, Andolsen said the annual lectures were inspired by the work of her successor, Bryan Massingale, S.T.D., the current James and Nancy Buckman Chair in Applied Christian Ethics.

“His work made me aware that in our discipline, attention to racism as an issue has been surprisingly rare, given its social urgency. Not only is it rare, but also serious social analysis of racism appears only episodically in the official documents of the American Catholic bishops. Something will happen in society that focuses our attention on racism, and we’ll hear an idealistic statement from the bishops that denounces racism. But there won’t be any sustained attention,“ Andolsen said.

In response, she said she decided to support an annual event that would bring consistent attention to racism and theology—both at Fordham and beyond.

“Racism has frequently been called America’s greatest sin. I hope this lectureship gives insights to everyday people that help inform their conscientious stance on racism. It would also be wonderful if material from this lecture series came to the attention of the American Catholic bishops,” Andolsen said. “And I hope that this stimulates research among Fordham graduate students, faculty in the theology department, and other departments in the University. The scholarship available on questions of justice for African Americans and Native Americans is less than it should be in North America. There needs to be much more of it.”

“The great Jewish historian Salo Baron defined the ’lachrymose school of Jewish historiography,’ that long litany of suffering and persecution that for many defines Jewish life and history. Andy Markovits’s memoir is the anecdote to that school: a sunny, optimistic, and uplifting read,” wrote Martin Green, professor emeritus at Fairleigh Dickinson University, in a recent review for the Jewish Book Council. “It doesn’t gloss over the sadness of post-War Europe, but it shows how that lost world could produce a vital future and how a stateless, rootless person could nonetheless turn that condition into a fulfilled life.”

Markovits is a scholar whose work crosses many fields, including German and Austrian politics, anti-Semitism, anti-Americanism, social democracy, social movements, and comparative sports culture in Europe and North America. His book, The Passport as Home, is a reflection of his life as a scholar and beyond. In 2019, Markovits served as a panelist at PCS’s Global Symposium on Sports and Society, where scholars examined anti-Semitism in the sports world.

]]>“Ed, aren’t you a math teacher?” he asked.

Yes, said Burger, president of Southwestern University, a mathematics professor, and the author of a new book called “Making Up Your Own Mind: Thinking Effectively through Creative Puzzle-Solving,” which was the subject of his presentation at Fordham College at Rose Hill on Oct. 3.

The boy asked him for help. Burger scanned the math problems. Try the question about donuts, he suggested. But Seamus was stumped.

“He was, basically, intellectually constipated,” Burger remembered. “He was pushing and pushing, and not one idea would come out.”

So they tried something different.

“When I say go, I want you to give me an answer that you’re confident is wrong,” said Burger.

“16!” Seamus immediately said.

The boy was wrong, but he was close. And that was the point. Instead of just sitting there, trying to solve a problem he couldn’t, he took action. He ignored the pressure of getting the right answer, got a wrong answer, and learned from his mistakes. And once he did, the right answer wasn’t far behind.

“Effective failure is how you respond to failure. So the failing itself—not that interesting or important,” he said. “It’s what you do next.”

Solving Real-World Problems through Effective Thinking

This concept—intentionally failing, and then gaining a different perspective that allows you to grow and react in a meaningful way—was the foundation of Burger’s presentation, “Making Up Your Own Mind: Thinking Effectively through Creative Puzzle-Solving.”

“Now, to be clear, I’m not suggesting that you do this on your final exam,” he told the students at the lecture. “But it’s an intermediate step.”

The lecture, co-sponsored by the Rose Hill dean’s office, the math department, and the Graduate School of Education, was about how to think more effectively and creatively in our daily lives. Burger’s advice, he said, could apply to all aspects of life: work, academic, personal.

Failing effectively was just one part of a three-part formula that Burger developed and described to the audience gathered in Keating Hall.

Understand simple things deeply. Don’t try to understanding something that, at first glance, seems very complicated, Burger said. Focus on something simple that’s related to that complicated problem. Examine it at a “subatomic particle level,” until you’ve noticed some feature that didn’t register before. “You’ll begin to understand that simple thing deeper, and then the more complex thing that you were first struggling with becomes easier to think about.”

Add the adjective. When you approach a math question, your first instinct is to solve it, said Burger. That can be a bad approach if you’re not fluent in the material. “Back up. Force yourself to describe it. Add as many descriptors as you can to describe the thing that you’re looking at. And every word that you add is going to reveal something you otherwise wouldn’t have seen,” he said.

Fail intentionally. Failure is good for you, he emphasized—as long as you gain some new insight from that failure, and then respond in a thoughtful way.

The audience was riveted. “How did you come up with this stuff?” asked one man.

It was an idea that was more than 20 years in the making, said Burger. He integrated these three steps into a class he developed at Southwestern University, where he gave students puzzles on which to practice this mindset, and eventually encouraged them to apply it to their own everyday lives.

After explaining the three-part approach, Burger quizzed his audience with a problem from his new book.

On a projector screen, he presented pictures of three black-and-white chess boards. The first one was normal. The other two were truncated: the second board was missing its northwestern and northeastern corners; the third one was missing its northwestern and southeastern corners.

“Imagine that you have a whole bunch of dominos, and each domino will cover exactly two squares,” he said. “And so the question is, can you cover each chess board with dominos so that every domino covers two squares, every square is covered, and no square is covered by two dominos?”

For two minutes, he said, apply those three practices to a puzzle. Brainstorm with the strangers next to you. And don’t actually solve the puzzles. Practice this way of thinking, and see where it leads you.

Each chess board had an even number of squares. The first board had 64.

“Sixty-four is a big number. What if I thought about a smaller chess board?” Burger said. “So understand simple things deeply.” Using a black ballpoint pen, he sketched the simplest version of the normal board—a two-by-two version.

And then, after drawing mini versions of the other two boards, an audience member “added the adjective.” The chess boards, said the audience member, were “white and black.” In a regular chessboard, a Domino needs to cover a white square and a black square, Burger reasoned. Then the audience noticed something different: the colors of the tiles that were removed. In the second board, a black and white tile were removed. In the third board, two black tiles were removed. Thus, the third board would not work.

“Now you realize that the missing squares in the second case were a different color, and the missing squares in the last case were actually the same color,” Burger said. “Just within a matter of minutes, you’ve looked at something that you’ve seen your whole life in a different way.”

“Just using those three things, you now see a chess board differently. And in some sense, I think that’s a metaphor for what we have within ourselves—the power we have through our own thoughts, when harnessed effectively, to see everything differently,” he continued. “And more magically.”

]]>Wisdom and Learning.

Inspired by this motto, Patrick J. Ryan, S.J, Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society, made it the central focus of this fall’s McGinley Lecture, which took place Nov. 15 at the Lincoln Center campus and Nov. 16 at the Rose Hill campus.

The lecture, “Wisdom and Learning: Higher Education in the Jewish, Christian and Muslim Traditions,” acted as a conversation between the traditions of the People of the Book, with Magda Teter, Ph.D., Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies, representing Judaism, and Ebru Turan, Ph.D., assistant professor of history, representing Islam.

Father Ryan noted that the notion of wisdom is prevalent in all three religious traditions because it “enables us to attain to an overarching moral and spiritual perspective on our world.”

“It prompts us to discern how learning or knowledge should be used and how to live as perceptive and virtuous citizens of our world,” he said.

Just as the three traditions share spiritual roots, they also share educational ones; some of their structures of higher learning all come from the ancient Greeks. However, as the religions began to develop and change, so did their educational structures.

“The Jewish and Christian and Muslim traditions of education have diverged greatly on the detailed contents of their curricula,” said Father Ryan.

In the Jewish tradition, education is an important aspect of the faith’s identity, said Teter, who talked about the difficulties Jews faced in the modern era when entering institutions of higher education.

“Jews were excluded from education until the 19th century,” said Teter, “and even when they were accepted, many schools did not support Jewish studies—or forced the students to learn from the Christian perspective. They lost their identity in their own story.”

The Jewish response was to create its own educational institutions, which began to thrive in the early 1900s, she said. It allowed Jewish populations to continue spiritual instruction outside the synagogue and the home, creating the chance to integrate into society.

Islamic instruction, which is heavily based on the memorization of the Qur’an, embraced higher education because it standardized Muslim beliefs, said Turan.

“Higher education provided a cohesiveness and unity to medieval Islam,” she said. “It gave Islam a global identity.”

Muslim schools called madrasas, derived from the Arabic word “to learn,” focused on law, theology and logic in their earliest iterations. Now, there are Muslim universities around the world that provide a diverse selection of study. Turan said that the translation of the Qur’an into other languages allowed Islam to be studied by a greater population.

“The translation . . . empowered Islamic education and opened it up to the rest of the world.”

In the Catholic tradition, Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, complimented university education with humanistic studies. By drawing from his own experiences at the University of Paris, Ignatius wanted to ensure that his students “went through systematic humanistic training in grammar, literature, and rhetoric.”

Jesuit education evolved around this foundation and now includes a diverse selection of fields of study. Father Ryan stressed that Ignatius’ humanistic training is ingrained in Jesuit education’s infrastructure.

“No one finishes any undergraduate college at Fordham without some exposure to philosophy, theology, literature, the natural and social sciences,” he said.

A Q&A segment following the lectures raised the question “Will the three faiths ever agree on the definition of wisdom?”

In response, the panelists laughed.

“We are all conscious that wisdom is important to our faiths and recognize it is something worth pursuing,” said Turan. “But besides that, I think we are fine agreeing to disagree.”

–Mary Awad

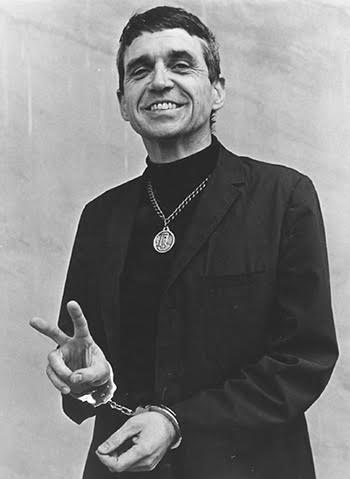

]]>That was the question posed on Oct. 23 at “Keep Fracturing the Good Order: Daniel Berrigan, the Long Haul, and the Big Heart,” a lecture that celebrated the life of Daniel Berrigan, S.J., and advised on how to survive peacefully in today’s world.

Speaker Anna J. Brown, Ph.D., of St. Peter’s University in Jersey City, New Jersey, was a friend and colleague of Father Berrigan. She met him through the Kairos Community, a peace community Father Berrigan started in the late 1970s. She described him as a “human being who was deep in prayer, faith, and soul.”

“Dan spent his life fiercely committed to nonviolence, being genuinely loving to all and centered in faith and community,” said Brown. “He constantly worked for peace in the world.”

Father Berrigan is remembered as “sometimes an anarchist, always a pacifist” who spent his life protesting against violence and “American military imperialism.” As one of the Catonsville Nine Catholic activists, he became the first priest to be on the FBI’s most-wanted list, for burning military draft files. With others, he became a symbol of the anti-war movement during the United States’ involvement in Vietnam.

Father Berrigan served as Fordham’s poet-in-residence from 2000 until his death in April of this year, and often spoke to classes, in conjunction with the Peace and Justice Studies Program. He was a peace activist until his death.

“He participated in the Occupy Wall Street Movement when he was 90 years old,” said Brown. “He was so dedicated to peace and fairness, he gave everything he physically could.”

The lecture focused on key events, such as climate change, weapons dealing, war, and mass migration, that hamper the quest for peace. Brown invited those in attendance to join “the tribe of big hearted people” who act as bearers of light for the world.

“We, like Dan, must be the opposite of hyper-individualism,” said Brown. “We must root ourselves in a community that pulsates love and radiates life.”

The event marked the Tenth Annual Julio Burunat, Ph.D., Memorial Lecture. Burunat, a Fordham alumnus who received doctoral degrees in both philosophy and theology from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, lived Murray Weigel Hall on the Rose Hill campus as a Jesuit scholastic. Theology professor J. Patrick Hornbeck II, D.Phil., said the series hosts talks that “advance conversations about theology and religion that are both appreciative and critical.”

“We consider sharing these conversations with the broader world an obligation,” said Hornbeck. “We feel honored to extend these experiences to people who otherwise would not be able to have them.”

–Mary Awad

]]>Thursday, October 3

6:30 p.m.

McNally Amphitheatre, Fordham School of Law, Lincoln Center campus

Mary Jo White was sworn in as the 31st Chair of the SEC on April 10, 2013. She arrived at the SEC with decades of experience as a federal prosecutor and securities lawyer. She served as the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York (1993-2002), as the First Assistant U.S. Attorney and later Acting U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York (1990-1993) and as an Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York (1978-1981) and Chief Appellate Attorney of the Criminal Division.

Following her service as the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, White became chair of the litigation department at Debevoise & Plimpton in New York.

White has received numerous awards in recognition of her outstanding work both as a prosecutor and a securities lawyer.

For additional info, contact Ann Rakoff at (212) 636-7985 or [email protected]

]]> |

| General Peter Pace, USMC (Ret.), delivering the Flaum Leaderhip lecture Photo by Chris Taggart |

After 40 years of serving in the military, including two spent as the 16th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Peter Pace, USMC (Ret.), has learned a thing or two about what it takes to be a leader.

He shared those insights on Sept. 24 at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus, when he delivered the Graduate School of Business Administration’s Flaum Leadership Lecture.

Pace delivered “Leadership Biases,” rich with anecdotes from his long and storied military career, to an audience that included a cohort of military veterans. He recalled how, as a second lieutenant serving in Vietnam, he radioed a commanding officer three times to ask which way he thought the patrol he was leading ought to be heading. Pace recalled that, on his asking the question a third time, his commanding officer responded with nothing but curse words.

“I promised myself that if I ever got chewed out again, it was going to be for going too far. If you are in a healthy organization and you are a young executive, that organization expects you to push out [on your own]a little bit, to make mistakes. That’s how you learn,” he said.

He came across another example in 1972. While working on his master’s degree, Pace said he read about a young executive at who’d lost $10 million for his company.

“The senior executives wanted to fire this guy [but]the CEO said something that I never forgot. He said, ‘Why would I want to fire someone I just paid $10 million to educate?’” Pace said.

“Now, if he makes the same mistake again, fine. But think about it. If you have subordinates who are honestly coming to work and doing their best, [even if]they’re making mistakes, that’s not all that bad.”

On July 30, 1968, a member of Pace’s squad was killed by a sniper while on patrol in Vietnam. Infuriated by his death, Pace said he called in an artillery strike on a village where the he believed the sniper had fired from. A subordinate, his platoon sergeant, shot him a look that made him reconsider—and sweeping through the village on foot, they found only women and children.

Pace said he didn’t know how he could live with himself today had his subordinate’s look not changed his mind.

“You will be morally challenged when you are the least emotionally prepared to deal with it. And if you don’t pick your anchor right now and decide who you are, morally you will not respond the way you want yourself to,” he said.

He said that many students may not remember most of what they’re taught at the University “but you will have ia way of thinking, and a way of problem solving, and a way of envisioning things that you will [apply]through your entire life. It’s not that you know exactly what you’re going to do; it’s that you know you have a moral compass.”

To see video of General Pace’s remarks, click here.

]]>