Amy Uelmen, a lecturer at Georgetown University, was one of those in attendance. Uelmen, who would join Fordham Law School in 2001 as director of the Institute on Religion, Law and Lawyer’s Work, said she knew something big was afoot at the time.

“There was this sense of, how do we carry forward this thirst for integrity in our personal lives and our professional lives? I had the impression that there was a seed of something new,” she said.

“If you work for the poor or the homeless, it’s obvious in some ways how Catholic values dovetail with that, but if you’re working for large companies or in a large firm setting, it’s not so obvious. So, I think there was an opening to go to these areas that are less clear, and in some ways, a little bit more difficult to thread out the connections.”

A Reunion for Scholars

Uelmen will rejoin many of the attendees of that 1998 conference on Thursday, as the Institute marks the anniversary of it and a similar conference in 1997, at Religious Lawyering at Twenty, a two-day event sponsored by Fordham Law at the Lincoln Center campus. She will join the Honorable David Shaheed, retired Superior Court judge and associate professor at Indiana University’s School of Public and Environmental Affairs, for a panel, “Humanizing Legal Education.”

On Friday, Fordham Law professor Russell G. Pearce, will lead a panel discussion, “Religious Lawyering at Twenty: In conversation with the next generation.” Pearce, who is also the Edward and Marilyn Bellet Chair in Legal Ethics, Morality, and Religion, was instrumental in organizing the original conferences.

Uelmen said that while Pearce had taken Tom Shaffer’s 1981 treatise “On Being a Christian and a Lawyer” and applied it to the tenets of Jewish Law, one of the noteworthy developments to come out of the 1998 conference was the involvement of the National Association of Muslim Lawyers, which had formed just two years earlier. One of the founders, University of Wisconsin Law School professor Asifa Quraishi-Landes, will be on the panel with Pearce.

When it comes to the past, she said she was excited to honor Howard Lesnick, the Jefferson B. Fordham Professor of Law Emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. Lesnick, who retired last year, wrote core texts such as Religion in Legal Thought and Practice (Cambridge University Press, 2010) and The Moral Stake in Education, (BookSurge, 2009).

“We’re going to celebrate how Howard brought his insight into the implications for teaching pedagogical practice and helped students become more human, basically,” she said.

Looking Ahead to the Future

The conference will not only be a retrospective; Uelmen said she’s hopeful that the conferences’ panels, celebrations, and workshops will also highlight the work of scholars who are just getting started. Their input is particularly important, she said, because they’re working in an environment that is very different from 1998. In fact, Uelmen returned to Fordham in 2016 to co-teach a workshop on having difficult conversations.

“We’ve spent, in many ways, the last 20 years becoming increasingly politically polarized, which makes it difficult to meet each other, hear each other, and figure out how to exchange stories and ideas,” she said.

“It’s a wonderful thing to get together in person, and make some personal connections and figure out how we can bring ahead a really humanized approach to having difficult conversations where we might substantially disagree on important questions.”

]]>Imitation can take on many forms—behavior, manner of prayer, and even dress, said Father Ryan, the Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society at Fordham. He cited several traditional and conservative aspects of imitation that eschew modernity.

‘A Clear Path of God’s Command’

He noted that the dress and appearance of Hasidic Jews mirrors that of past rabbis, “mystical masters” known as zaddikim. And while their dress may look different from modern street clothes to an outsider, he said, it is through “their very difference that they demonstrate their imitation of past rabbis and their fidelity to God.”

“To imitate one’s zaddik, to walk in the paths of ancestors in the faith, lies close to the heart of what the faith of Israel has meant for nearly four millennia,” he said.

Likewise, in Islam, accounts of what Muhammad said and did were written down to guide “requirements of ritual purity” that validate worship and all other aspects of life.

“We have put you on a clear path of God’s command. Follow it and do not follow the vagaries of those who know nothing,” Father Ryan said, quoting the Qur’an (45:18).

“Muslims have taken [this]divinely guided way of proceeding in every aspect of life more seriously and more literally than have Christians; in this they more closely resemble Orthodox Jews,” he said.

Each religion varies on the degree to which the followers adhere to such imitations, he said. In the case of Christianity, he cited St. Paul: “Be imitators of me as I am of Christ” (1 Cor 11:1).

He noted that the monastic movements in first-millennium Christianity withdrew from the “corrupting secular world” while “Carmelites Franciscans, Dominicans and Augustinians, most prominently, sometimes engaged with the secular world but also withdrew from it into their convents from time to time.” In the late 14th century, however, starting in the eastern Netherlands, the Devotio Moderna movement appealed to laity and the lower ranks of the clergy, urging them to engage with the world but to eschew its corrupting standards, imitating the poverty and simplicity of Christ. The movement began with popular Catholic preacher Geert Grote, who died in 1384, but was most famously memorialized by Thomas à Kempis and his devotional book Imitation of Christ.

Father Ryan noted that in the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, the one making the exercise asks to “to imitate [Jesus] in enduring every outrage and all contempt, and utter poverty, both actual and spiritual.”

Imitation in the Age of Smartphones

Following the lecture, the conversation took a contemporary turn when the evening’s moderator, William F. Kuntz Jr., a judge of the Second Federal Court in the Eastern District Court of New York, reflected on whether it was possible—in this age of smartphones—to turn away from modernity and imitate God and the prophets in a traditional manner.

“What would each of the faith traditions say about the innovations of Facebook and the internet?” he asked.

“There’s a strand with every religion that has a problem with any innovation,” said Rabbi Daniel Polish, Ph.D., of Congregation Shir Chadash in Poughkeepsie, one of the lecture’s respondents. “There’s a tension between those that refuse to adapt and early adapters.”

Father Ryan agreed. “There were condemnations of the railroad in the 19th century by the papacy,” he said.

Yet times change and technology moves forward. So how is one to adapt to modern times and yet remain faithful?

Zaki Saritoprak, who holds the Nursi Chair in Islamic Studies of John Carroll University and was also a respondent, said that like any technology, its value depends on how it’s used.

“You have a car; you can drive to a good place or bad place,” he said. “If [technology]prevents you from your major duties, like your responsibility to pray, then it becomes problematic.”

And yet, the same innovations can help with prayer, said Rabbi Polish, noting how many religious texts are now available online.

“The extreme Orthodox have made use of cell phones to access vast storehouses of information,” he said.

He recalled a recent service within the Hasidic community. “When it comes time to pray, they all pull out the cell phone and open to the appropriate app,” he said. “We were praying literally off our phones.”

Related Coverage: Anthropologist Researches Internet Use in Ultra-Orthodox Communities

]]>Father Patrick J. Ryan, the Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society, suggested that the collisions of various empires might have signaled, supported, and even inspired reformation in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

“Sometimes reformation has happened in reaction against colliding,” he said at the Nov. 14 lecture at the Lincoln Center campus. “At other times, the very collision of worlds has sparked reformation.”

Jerusha Tanner Lamptey, Ph.D., an assistant professor of Islam and interreligious engagement at the Union Theological Seminary, and Rabbi Daniel Polish, Ph.D., the spiritual leader of the Congregation Shir Chadash, acted as respondents to Father Ryan’s lecture.

A ‘tragic irony’

Father Ryan’s lecture, which coincided with the fifth centenary of the Lutheran reformation, took into account the reform movements that were incited by Kings Hezekiah and Josiah as well as the prophets Isaiah and Jeremiah. He also explored 19th century Reform Judaism.

“Reform Judaism enabled many hitherto purely nominal Jews or immigrant Jews to understand two basic elements of the faith, the oneness of God and the call of the chosen people to spread the light of monotheistic faith,” he said.

In the case of Christianity, Father Ryan stressed that the collisions of both empires and cultures have been significant in the Protestant reformations as well as the Anglican and Catholic reformations. He said that in the late 15th century, Europeans first encountered new worlds in the Americas, Asia, and Africa. But the agents of the Catholic reformation were more likely to evangelize these populations than Protestants, he said.

Father Ryan emphasized that Martin Luther was, however, eager to convert Jews after becoming convinced by Saint Paul’s Letter to the Romans that salvation would come to the Jews only after the evangelization of Gentiles was complete. The Lutheran reformation went down a dark path in 1543 when Luther published anti-Semitic writings that called for the violent destruction of the Jews.

“All of us who call ourselves Christian, heirs of one or another reformation—Protestant, Anglican or Catholic—need to examine our past in such a way as to liberate ourselves and our world from imprisonment in history,” he said.

Rabbi Polish likewise acknowledged Luther’s anti-Semitism, but said he was also struck by the commonalities of Reform Judaism and Lutheranism. Just as Luther rejected practices of the church that were not directly mandated in scripture, early reformers of German Judaism rejected the notion of an authoritative rabbinical interpretation of scriptures.

“Both Luther and early Jewish reformers shared commitment to the vernacular,” he said, adding that early Jewish reformers believed in a “perfect symbiosis of their German culture and their Jewish inheritance.”

Of course, this became a tragic irony in the context of the Hitler era, he said.

“The futile aspiration of early reformers to be accepted by their fellow Germans ended with the extermination of their community,” he said.

Authority in the past, present, and future

In his assessment of reform in Islam, Father Ryan affirmed that the first Muslims in seventh-century Arabia saw Islam as “a reform of what had come earlier in the Jewish and Christian tradition of faith.”

“Muhammad’s prophetic vocation made him, in the Islamic theology of history, the last of a series of great prophets and especially of those prophets who are characterized in Islamic tradition by the term rasul, messenger,” he said.

Father Ryan noted that between the 15th and the 19th centuries, Muslims like the Egyptian polymath Jalal al-din al-Suyuti and the northern Nigerian Usumanu dan Fodio considered themselves to be mujaddids or reformers of Islam.

Self-described Mahdis or messianic leaders also started uprisings in Sudan and Saudi Arabia in 1881 and 1979, which coincided with the start of the 14th and 15th Muslim centuries.

Like the leaders before them, these reformers believed that they were responding to perceived threats to the Islamic tradition by great empires or repressive regimes, Father Ryan said. There are some echoes of this as well in the ISIS insurgency that assailed Syria and Iraq after 2014.

“That the partisans of ISIS first chose to create their ideal state across the borders of Iraq and Syria demonstrates how much ISIS is a delayed response to and reaction against European colonial parceling out of the central Arab world in the aftermath of World War I,” he said.

Lamptey cited trends in recent Islamic feminist interpretations of Islam as concrete examples of contemporary Islamic reform. She said these distinct interpretations were focused on egalitarian or a recovery of “real Islamic tradition’.”

“They argue that the Quran is fundamentally egalitarian, that it depicts an undifferentiated, ungendered human creation, [and]a divine sovereignty….and that the Quran is silent on any accounts of women in a secondary status,” she said.

While the Islamic feminist pioneers recognized that there were limitations and discrepancies in these interpretations, she said they attributed them to context and human interpretation.

“They seek to address those concerns by returning to the supposedly pristine beginnings and uncorrupted sources of the Islamic tradition,” she said.

]]>A child survivor of the Holocaust was reluctant to share his family’s full story, until he saw a picture of himself as a 4-year-old boy at Auschwitz on a website denying the Holocaust

For years, Michael Bornstein, PHA ’62, wished he could wash away the serial number—B-1148—that was seared into his left forearm when he was just 4 years old. He’d mention Auschwitz, if asked about the tattoo, but he wouldn’t dwell on the Nazi death camp where his father, brother, and nearly 1 million other Jews were murdered during World War II. He’d seldom speak of being separated from his mother, who withstood beatings from female guards as she smuggled bread and thin gray soup to him in the children’s barracks, and who later smuggled him into the women’s barracks before she was sent to a labor camp in Austria. He wouldn’t say much about how his grandmother somehow, improbably, kept him alive long enough for them to be among the 2,819 prisoners liberated by Soviet soldiers.

His recollection of those dark days is dim—“a blessing and a curse,” he says. He seems to recall the stench of bodies burning, the smoke rising from crematoria chimneys, the quickening clack of guards’ boots. But he’s also aware of the malleable nature of memory, how the things we recall, especially from early childhood, are shaped by some inscrutable mix of perception, imagination, and the stories we’re told. And so for years he stayed mostly silent about his past, not only because it was traumatic but also because so much of it—the texture of his brother’s hair, the sound of his father’s voice—was inaccessible to him.

He preferred to look forward, with an optimism he says he inherited from his mother. Gam zeh ya’avor, she’d tell him, quoting the motto she and her husband shared during the war. This too shall pass. He can still hear the sound of his mother’s voice because she found him in Żarki, Poland, after the war. In February 1951, when he was 10, they immigrated to the United States, where he’d go on to build a career in pharmaceutical research and—with his wife, Judy—raise four children in what he calls “a life filled with soccer games, birthday parties, and bliss.”

As his kids grew up, they began pressing him for details about his past, but he’d always resist a full recounting. Now Bornstein is 77, and his children have children of their own. Several years ago, when Jake Wolf, the eldest of his 11 grandkids, started asking questions, wanting to use the information for his bar mitzvah project, Bornstein couldn’t say no. He began to open up.

Then he saw something that left him stunned and more determined than ever to tell his story: a picture of himself as a boy at Auschwitz on a website claiming that the Holocaust is a lie, that it never happened. “I slammed my computer shut in disgust. I was horrified. My hands shook with anger,” he writes in Survivors Club: The True Story of a Very Young Prisoner of Auschwitz, published last March by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. “But now I’m almost grateful for the sighting. It made me realize that if we survivors remain silent—if we don’t gather the resolve to share our stories—then the only voices left to hear will be those of the liars and bigots.”

Bornstein wrote the book with his daughter Debbie Bornstein Holinstat, a TV news producer who for years had urged her father to work on such a project. She helped him plumb his earliest, darkest memories, and together they searched historical records and interviewed relatives and others who knew his family in Poland. In the process, they discovered a detail that helped solve one of the biggest mysteries of his survival, and he learned much about the resolute, resourceful father he never got to know. Together, they reclaimed a family heritage, illuminating stories of loss and resilience that had been left largely untold for 70 years.

Żarki, Open Ghetto

Michael Bornstein was born on May 2, 1940, in the Nazi-occupied town of Żarki, Poland, the second son of Sophie Jonisch Bornstein and Israel Bornstein, baby brother to 4-year-old Samuel. They lived in a redbrick house on Sosnawa Street.

In some parts of Poland during the late 1930s, Jews couldn’t own land, and their business dealings were restricted. But Jewish-owned businesses thrived in Żarki, where more than half of the town’s population, approximately 3,400 residents, was Jewish. Bornstein’s father was an accountant, and his mother’s brother Sam Jonisch (one of her six siblings) ran his family’s leather tannery in town.

That changed on Friday, September 1, 1939, when German forces invaded Poland, reaching Żarki the following day with an aerial attack that torched some homes and businesses. Sophie, newly pregnant with Michael, wanted to check on her parents, who lived nearby. But Nazi storm troopers had already moved onto the streets. On Monday, when all Jewish men in Żarki were ordered to report for labor shifts, Sophie left Samuel with her mother-in-law, Dora, and set out to find her parents. As she neared the Jewish cemetery, she saw German soldiers command a family she recognized from synagogue to strip naked. As mother, father, and young daughter huddled together, the soldier fired three shots, and the family fell dead in the ditch the father had just dug. It was a scene that haunted Sophie Bornstein her entire life.

The Nazis murdered more than 1,000 Jews in Poland that day, including 100 in Żarki. Such atrocities brought out the worst in some gentile residents, Bornstein and Holinstat write. “Many Catholics had not liked living among Jews before the war. Now they blamed the town’s Jewish people for making them the target of German bombings.”

In October, as Nazi soldiers went door-to-door confiscating Jews’ money and jewelry, Israel Bornstein sought to safeguard his family’s valuables. He gathered what he could in a burlap sack—a string of pearls, a stash of banknotes, the family’s small silver kiddush cup—and buried it in the backyard.

Żarki was still an open ghetto at the time, which meant that it wasn’t surrounded by fences, but Jews couldn’t come and go as they pleased. The Nazis shut down or took over Jewish businesses, enforced a strict curfew, and made Jews wear white armbands with a blue Star of David on them. They also forced them to create a Judenrat, a council of Jewish leaders. The town elders elected Israel Bornstein to serve as president. It was not a coveted role. Many Jews in Eastern Europe came to see Judenrat members as traitors, simply doing the bidding of the Nazis, and in Żarki people viewed Israel with suspicion.

But in their research, Bornstein and Holinstat found a collection of essays and a detailed diary written in Hebrew that told of Israel Bornstein’s heroic, often successful efforts to make conditions more bearable. In Survivors Club, they describe how he collected money from fellow Judenrat members and used the funds to bribe Gestapo officers, helping to obtain 200 legal travel visas for families trying to leave Żarki, for example, and saving the life of a teenager who faced execution because he was too sick to work one day.

“Though it’s sometimes seen as a very negative position, my father used it to save people. He set up soup kitchens. He was a very good man. And it made a lot of difference to me knowing that he was a good man,” Bornstein says. “That’s one reason we called the book ‘Survivors Club,’ because my mother’s six siblings all survived, and part of it has to do with my father, who encouraged them to go into attics, basements, wherever they could go to survive.”

By October 1942, however, the call had come for Żarki to be made Judenrein, “clean of Jews.” Most of those remaining were sent by train either to labor camps or to extermination camps. The Bornsteins and approximately 120 others were allowed to stay behind as part of a cleanup crew, but eventually they too were sent away, to a labor camp in Pionki. And in July 1944, when that camp closed, they were packed onto trains bound for Auschwitz.

“Sickness Saved My Life”

Upon arrival at Auschwitz, like all families, they were split up: Israel and Samuel were assigned to the men’s side. Michael initially stayed with his mother and grandmother until guards shaved his head and tattooed his arm. He was sent to the children’s barracks, where some older kids looked out for him, warning him to hold his nose as he drank down the smelly gray soup. Other kids stole his bread. Sophie was sent to the women’s barracks with Michael’s grandma Dora. She risked her own well-being to find her son and eventually bring him into the women’s barracks, where he hid under straw, in corners, scattering at the sound of guards approaching to take roll call.

While Sophie was able to protect Michael, she was helpless to save her husband and young Samuel, who died in September from the effects of Zyklon B gas—the Nazis’ preferred method of execution at Auschwitz, where as many as 6,000 people per day were killed in gas chambers. “[My mother] later told me that her heart literally felt like it had been gouged from her chest with an ax” when she learned of their fate, Bornstein writes. Soon, however, she was sent to a labor camp in Austria, and Michael was left alone with his grandma Dora.

By January 1945, with Soviet forces closing in on Auschwitz, the Nazis started to evacuate the camp, forcing an estimated 60,000 prisoners on what came to be known as a death march to concentration camps in Germany. Many prisoners, already frail from malnutrition, died from exposure in the harsh winter. But Michael and Dora evaded the march, and Bornstein always wondered how.

Not long ago, while visiting Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial museum in Israel, he discovered a document that solved the mystery. Nazi records indicate that he was in the infirmary at the time, diagnosed with either diphtheria or dystrophy (the writing is unclear). And his grandmother was with him. “The name doesn’t really matter,” he writes in Survivors Club. “That piece of paper recovered by a museum years after the war made one miracle clear. Sickness saved my life.”

On January 27, nine days after he found refuge in the infirmary, Soviet troops arrived. A couple of days after liberation, Dora carried Michael out to freedom, a scene captured on film by Soviet cameras. “Of the hundreds of thousands of children who had been delivered by train to Auschwitz, only 52 under the age of eight survived. They were the world’s best hiders,” Bornstein writes. “I was one of them.”

Postwar Dangers and the Cup of Life

Bornstein’s freedom brought with it a new set of dangers. “I would like to tell you … that all of us went home and lived happily ever after,” he writes. “But it wasn’t like that at all.” Four out of 10 Jews who survived the concentration camps died within a few weeks of the arrival of the Allied armies. Those who did survive found much of Eastern Europe unsafe for them, particularly in Poland, where anti-Jewish sentiments led to a series of murderous pogroms.

Soon after liberation, Michael and Dora returned to Żarki, where they found the family home on Sosnawa Street had been seized by a Polish family who now saw it as their home. Dora took Michael to a farm on the edge of town, where they found shelter in a chicken coop. They would periodically head into what had been the Jewish quarter, where they met relatives who were, miraculously, among the few dozen Jews (out of 3,400 six years earlier) to return to Żarki after the war. One day, as Michael and Dora walked in town, he spotted his mother, who had made her way back from Austria. “If we had both seen more horror than the world knew it could hold—then this moment was the opposite of that,” he writes. “This was the opposite of despair.”

Sophie realized that there was little opportunity left for them in Żarki. But first she tried to recover the valuables her husband had buried. “At night, even though the house was occupied, she went digging with her bare hands to try to find these things, jewels and money, and the only thing that she found was the kiddush cup, which is a cup that you make blessings with,” Bornstein says.

“And so this cup has been in our family ever since. It’s been at my wedding, at our kids’ weddings, at their bar mitzvahs, bat mitzvahs, and so on. It’s not worth much if you buy it for the silver, but we cherish it quite a bit.”

In Munich, Waiting on Passage to America

After the war, Dora decided to remain in Poland, but Sophie determined that she and Michael would apply for visas to the United States. “She said the word ‘America’ the way a child says the word ‘candy,’” Bornstein writes. “She told me America was the most wonderful and welcoming place you can imagine.” That was not the case for them in Żarki or in Munich, where the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society assigned them to a displaced persons camp and, later, to a one-room apartment in the city.

“The German kids were bullies,” Bornstein recalls. “I had no hair on my head, I was skinny, and I didn’t speak the language, so I was bullied quite a bit.” Sophie bought flour and nylons from American soldiers and sailors in Munich, and sold the goods on the black market. It was a risky way to make a living, and Bornstein feared that she’d be arrested and he’d lose his mother again. But after nearly six years, they received their visas and set off on the USS General M. B. Stewart, arriving in New York City in February 1951.

With help from aid organizations, they eventually settled in a small apartment on 98th Street and Madison Avenue. Sophie worked as a seamstress, making $30 a week, and Michael attended P.S. 6. “I was this little kid who didn’t speak much English and had a tattoo on his arm. The teachers didn’t say anything, so I was pretty much alone and didn’t have friends,” recalls Bornstein, who soon found a job that would prove to be consequential. “I worked at Feldman’s Pharmacy, at 96th and Madison, getting 50 cents an hour,” he says. “The head pharmacist, Victor Oliver, was very good to me. He kind of took me on as a father figure and sparked my interest in science.”

Oliver even attended Bornstein’s bar mitzvah, held at Park Avenue Synagogue, after which his mother gave him a gift that she’d been saving for years to buy him: a gold watch. “You have to wind it a few times a day to make it work, but it’s great,” he says. “And on the back, it has a gimel and a zayin, which are the Hebrew letters for gam zeh ya’avor, ‘This too shall pass.’”

“A Can-Do, Get-It-Done Type of Guy”

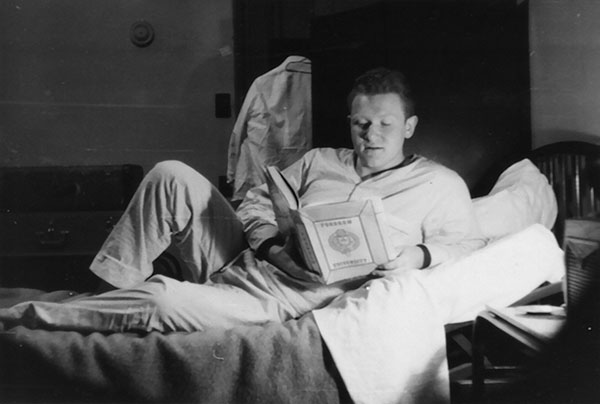

Bornstein’s mother also instilled in him a deep appreciation for the value of education. Like faith, she’d tell him, education can’t be taken away. In 1958, he enrolled at Fordham’s College of Pharmacy, just as she embarked on a new chapter in her life. “My mother remarried and moved to Cuba because her sister was there,” he says. She would later return to the States and settle in South Florida, but at the time, Bornstein says, “I was pretty much homeless, and Fordham didn’t have any room in the dormitories, so they put me up in the infirmary.” It was the second time in his life that an infirmary saved him, he says. “I would probably have skipped college if it weren’t for that.”

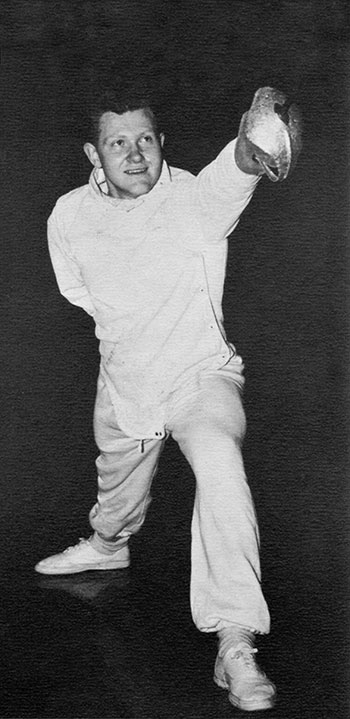

In addition to providing Bornstein with room and board, Fordham gave him a partial scholarship. He spent summers working in the Catskills to help pay any remaining tuition costs. “I was a chamber maid, then a busboy, then a waiter, and finally a head waiter,” he recalls. “The salary was only about twelve dollars a month, but the tips made it.” On campus, he found a niche on the fencing team.

One of his former Fordham classmates, William Stavropoulos, PHA ’61, recalls Bornstein as a “nice, friendly guy.” He says he and his friends in G House at Martyrs’ Court never would have suspected the horrors Bornstein had been through. “I remember distinctly sitting around one day and a guy asked Mike about his tattoo. He mentioned the camp and said his mother used to hide him here and there, keep him out of sight of the guards, but he didn’t say much else. He was always upbeat.”

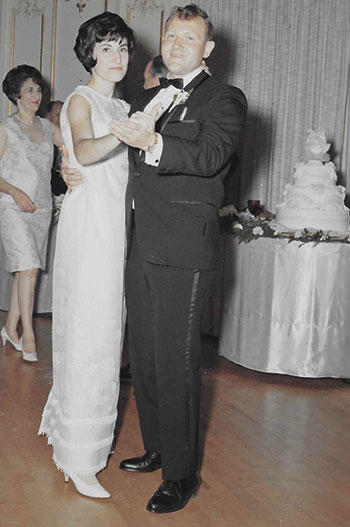

After graduation, Bornstein enrolled at the University of Iowa, where he earned a Ph.D. in pharmaceutics and analytical chemistry. But he says his greatest achievement there was meeting an undergraduate named Judy Cohan. “We obviously hit it off. He had the same interests I did, and he was persistent,” recalls Judy, who was studying special education. They attended movies and plays, and he accompanied her on visits to the children’s ward at local hospitals. “He was very caring of the children, and that was important to me.”

They were married nearly 50 years ago, on July 9, 1967, after Bornstein began his career at Dow Chemical in Zionsville, Indiana. While there, he reconnected with Stavropoulos, who had earned a Ph.D. in medicinal chemistry at the University of Washington and would go on to become chairman and CEO of Dow. The two, both newlyweds at the time, would see each other socially, and Stavropoulos even helped the Bornsteins move into their new apartment. But they lost touch over the years. “He went to work for Eli Lilly, and I stayed at Dow,” Stavropoulos recalls. In the late 1980s, Bornstein and his family moved to New Jersey, where he worked as a research manager for Johnson & Johnson, eventually rising to director of technical operations, a position that took him to Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, France, and elsewhere.

“He was a streetwise guy, and I always knew he was going to be a success,” Stavropoulos says. “When I think of Mike, I think of a positive, can-do, get-it-done type of guy. At Dow he was that way, and at Fordham too. It’s an incredible story. He’s obviously a courageous man.”

Fighting Intolerance with Compassion

Holinstat says her dad’s courage was especially evident during the process of writing the book. “My father is such a positive man, and he’s gone out of his way his entire life to show his kids and his grandkids nothing but positivity, so for him to dig deep and be willing to open up and talk to me about the deepest, darkest places in his memory was difficult for him, and it was hard for me because I knew how hard it was for him.” But the process has been well worth it, she says, explaining that they wrote Survivors Club with readers as young as 10 years old in mind.

“For my dad, a big piece of this was making sure that his grandkids understood the atrocities of the Holocaust. So it was really important to us to write something that the kids could grasp at this stage in their lives, and that they could share with their peers, because this next generation, most of them will grow up not having met a Holocaust survivor.”

In March, shortly after the book was published, it became a New York Times best-seller. The paper’s reviewer noted that the book combines the “emotional resolve of a memoir with the rhythm of a novel,” and that, although the book is marketed for young readers, “the equal measures of hope and hardship in its pages lend appeal to an audience of all ages.”

Holinstat waited decades for the opportunity to help her father tell his story, but she feels the timing of the book’s publication could not be more poignant or pointed, coming amid a recent surge in anti-immigrant and anti-Semitic sentiments in the U.S. “I truly believe that this story is being released now for a reason, to remind people what happens when bigotry goes unanswered,” she says.

The core moral lesson of the Holocaust, she and her father believe, is the ease with which any group of people can be dehumanized. “The world can never forget what happens when discrimination is ignored,” Bornstein said last April at Congregation Beth-El Zedeck in Indianapolis. “And it’s not just discrimination against Jewish people but against all minorities, and that includes Muslims, Mexicans, and African Americans. It’s time for compassion; it’s time for empathy.”

Bornstein plans to return to Poland this year with Judy, their children, and other family members. Holinstat has been communicating with people in Poland about establishing a Holocaust memorial in Żarki, and the family will be going to Auschwitz, which Bornstein visited in 2001 with Judy and in 2010 with his son, Scott.

In the meantime, Jake Wolf, the grandson who persuaded Bornstein to share his story, is preparing for his freshman year at Syracuse University, where he intends to major in both communications and business. “In our family,” he says, “it’s so important to know how difficult it was for my grandpa. He never had any hate toward the world for what he was put through. And that inspires all of us. If he could get through that with a smile on his face, we can do anything.”

A “Survivors Club” Reunion in the Suburbs

Since the publication of the book, Bornstein has heard from many people who have thanked him for telling his story, including some who understand all too well what he and his family endured. Sarah Ludwig was the 4-year-old girl standing next to Bornstein in the iconic photo from Auschwitz. Tova Friedman, then 6, stood just behind Ludwig as the children showed their tattoos to Soviet soldiers. The three survivors recently learned that they live just miles from each other in suburban New Jersey.

On Sunday, June 4, they gathered with kids, grandkids, and other relatives for a reunion brunch at Holinstat’s home that included prayers of remembrance and celebration, and the use of one precious silver cup. For Holinstat, it was a remarkable coda to the experience of helping her father tell his story after all these years.

“The last time they saw each other, they were kids wearing prisoners’ stripes,” she says. “Now they’re surrounded by family.”

—Ryan Stellabotte is the editor of this magazine.

Watch NBC Nightly News‘ coverage of the reunion.

]]>But this concept of authority and impartiality, according to Patrick J. Ryan, S.J., evolved a great deal over the years. In “Judging Justly: Judgment in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Traditions,” Father Ryan, Fordham’s Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society, explored how Jewish, Christian, and Muslim faiths contributed to that idea through their own unique traditions.

He framed his discussion of judgment with the tragic story of how three High Court judges in Ghana were murdered in 1982 precisely because they had given judicial redress to people convicted by a kangaroo court under a military regime.

In remarks delivered on March 28 and March 29 as part of the annual Spring McGinley Lecture,

Father Ryan delved into examples from scripture that illustrated how the faithful have struggled with concepts such as mercy and justice. In the Book of Genesis, he noted that God, whom Jews regard as the supreme judge, had a “crowded docket”: Weighing in on the fratricide of Cain, and condemning the corrupt and violent contemporaries of Noah yet sparing the ark-builder and his family.

In Christian scripture, he recalled an account in the Gospel of John, where Jesus is confronted by “the scribes and the Pharisees” asking him to judge a woman caught in the act of adultery. Jesus play-acted the role of judge, writing on the ground, and finally declaring, Jesus’ declaration “Let anyone among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.” illustrates the importance of impartiality and fairness.

“When Jesus finally rises from his play-acting, he finds that all the guilty accusers of the woman have departed, ‘one by one, beginning with the elders,’” Father Ryan said.

“One possible reason that the placement of this Gospel passage in the New Testament has proven so problematic may be that the discipline of the early church, in cases of adultery, was much less merciful than that of Jesus.” *

In Islam, as in Christianity and Judaism, God is also the ultimate judge, he said. His command and judgment are closely associated with the commands and judgments issued by the Messenger, the Prophet Muhammad. That practice continued after Muhammad’s death via judges who were concretized as the caliphs’ appointees in the Sunni tradition from the seventh to at least the 13th century, and the appointees of the imams in the Shi‘i tradition.

A qadi, or judge in the Sunni Muslim tradition, was appointed by the caliphs in the seventh century, and gradually began to exercise judicial functions in the eighth century, said Father Ryan. When the Turkish government suppressed the caliphate in 1924, however, a central religious-political institution was lost. Since then, Muslim judges are often appointed by national or regional governments. This has led to some controversial rulings in Nigeria, in particular, he noted, involving the amputation of hands for sheep-stealing, as well as overly zealous accusations of adultery against women based on circumstantial evidence only.

“Better trained Muslim judges, with expertise in comparative law and a broader vision of Islamic jurisprudence, can be found in many of the Gulf States,” he said. “But there have been highly problematic judgments handed down by judges, not only in northern Nigeria but also in Saudi Arabia and Egypt in recent decades.”

Respondents to Father Ryan’s lecture included Sarit Kattan Gribetz, Ph.D., assistant professor of theology at Fordham, and Ebru Turan, Ph.D., assistant professor of history at Fordham. Gribetz highlighted two passages from Genesis Rabbah and the Babylonian Talmud and one from the Torah that illustrate the ongoing debate between mercy and justice in God’s mind. God is compared to a king who holds up two empty cups and notes that they will crack when filled with cold water and burst when filled with hot water. The temperatures are stand-ins for too much mercy and too much justice.

“[They] represent radical extremes-order and chaos, suffocating restriction and unbounded freedom. Each on their own is assumed to be too dangerous—so dangerous that it will shatter, crack or deform the world,” she said.

Turan further developed Father Ryan’s history of how the role of judge developed historically in the Muslim tradition. The Ottoman Empire, from the 13th to the early 20th century, developed a system of training legal scholars for such posts. With the break-up of the Ottoman Empire after 1918, modern Turkey appoints judges with a much more secular orientation.

Father Ryan said offered three conclusions from the faith traditions’ experiences with justice:

-Judges need protection from manipulative politicians, established ruling classes, and populist demagogues. He cited as examples the Roman-dominated Hebrew sanhedrins, Pope Urban II commanding Christian knights to go on Crusade, and modern “Muslim muftis” who “declare every military adventure of a Middle Eastern dictator a jihad.”

-Judges should have excellent legal credentials, a deep understanding of the law in their own tradition, and a sense of comparative law. There is no room in the courtroom for mediocre judges.

-Judges benefit from differences in legal opinion, or “ikhtilaf,” an Islamic concept being promoted by movements concerned with the status of Muslim women. This contrasts with the generally approved idea of Islamic legal consensus, or “ijma,” relied on by Orthodox Jews, Catholic Christians, and the various Eastern Christian Churches.

]]>“He ensconced himself on the ambo in the center of the Royal Doors and delivered a thoroughly secularly speech extoling the fatherland and the church’s role in bolstering the fatherland,” said Father Galadza, the Kule Family Professor of Liturgy at Saint Paul University, Ottawa.

“Even during Romanov era the czar has never been allowed to speak from holy space of the Royal Doors.”

That “political intrusion into the sacred” became symbolic of the religious undertones of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, which was the topic of an Orthodox Christian Studies Center discussion at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus on Nov. 4.

“Putin’s campaign in Ukraine is tragic because the natural goodwill between Ukrainians and Russians that had predominated during period of Ukrainian independence is now being sorely tested,” Father Galadza said.

Because of the close ties between the Ukrainian and Russian Orthodox Churches, the Russian government has often employed religion to pursue its political aims, including fanning nationalistic flames within religious communities and even bringing criminal charges against clergy to pressure religious leaders.

“The fear is that Putin and the Russian Orthodox Church will swallow the Ukrainian Orthodox Church through the Moscow Patriarchate and bring Ukraine that way into Russia,” said Rabbi Yaakov Dov Bleich, the chief rabbi of Kiev and all of Ukraine.

Rabbi Bleich gave the example of his own experience in a government-organized group called the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches and Religious Organizations.

“We would come to meetings once a month and talk about essentially nothing because the agenda was set by government people,” Rabbi Bleich said about the organization, which has since claimed independence. “Basically, government took all the religious leaders, created an organization for us, then locked us in a room and threw away the key.”

The use of religion is just one smokescreen Putin has created to shape the ongoing conflict, said Adrian Karatnycky, nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council. Another is to spread propaganda casting it as a “civil war.”

“By now it may have the elements of a civil war, but it is a civil war that was constructed from outside,” Karatnycky said. “There were only a few thousand people disgruntled and engaged in protest at first. Then there was a wave of trained fighters who came to reinforce them. Now this is a fight by a new group of people empowered by money and weapons from the Kremlin.”

In reality, the conflict is a military incursion, not a civil conflict, panelists said.

“There is no civil war. It’s a bunch of terrorists who are getting arms from people who have an interest in retaining the situation,” said Rabbi Bleich.

“People ask, ‘When will there be peace?’ It won’t be with Putin. Putin doesn’t want peace now. He wants the situation to stay the way it is — instability, a war economy, not allowing Ukraine to develop into a thriving democracy with its own economy, which will could dominate Russia.”

The panel featured:

- Rabbi Yaakov Dov Bleich, chief rabbi of Kiev and all of Ukraine and vice president (Ukraine) of the World Jewish Congress;

- Father Peter Galadza, the Kule Family Professor of Liturgy at the Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky Institute of Eastern Christian Studies at Saint Paul University, Ottawa;

- Father Cyril Hovorun, research fellow at Yale Divinity School;

- Adrian Karatnycky, nonresident senior fellow at the Transatlantic Relations Program with the Atlantic Council;

- Olena Nikolayenko, Ph.D., assistant professor of political science at Fordham; and

- Moderator Aristotle Papanikolaou, Ph.D., the Archbishop Demetrios Chair in Orthodox Theology and Culture and cofounder of the Orthodox Christian Studies Center.

The panel discussion was co-sponsored through gifts received from the Jaharis Family Foundation, Inc., the Nicholas J. and Anna K. Bouras Foundation, Inc., and the Office of Alumni Relations at Fordham.

]]>For her efforts, the Jewish Book Council recently awarded Mitzvah Girls: Bringing Up the Next Generation of Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn (Princeton University Press), with the 2009 Barbara Dobkin Award in Women’s Studies.

In the book, which is one of 18 winners in the council’s annual book awards, Fader examined language, gender, and the body from infancy to adulthood to showing how Hasidic girls in Brooklyn become women responsible for rearing the next generation of non liberal Jewish believers. To uncover how girls learn the practices of Hasidic Judaism, she looked beyond the synagogue to everyday talk in the context of homes, classrooms, and city streets.

Fader will be honored along with her fellow winners on at a gala award ceremony on March 9 at the Center for Jewish History in Manhattan at 15 West 16th St. The awards ceremony, which begins at 7:30 p.m., is free and open to the public.

]]>For this visit, Roshi Kennedy will speak on the question, “What is it when the story ends?” He will bring to this his uniquely seamless experience of both Zen and Catholic practice, a subject very much in the air since Paul Knitter’s book, Without Buddha I Could Not Be a Christian.

When interviewed by the National Catholic Reporter in 2007, Roshi Kennedy said:

“I was talking with a Chinese Zen master once and he said one of the difficulties of dealing with Catholics is that they love their spiritualities … as if it was a parallel life,” Kennedy tells Tom Fox. Buddhists root us in this moment, he said. “Buddhists would say, ‘If God isn’t present in this moment, where is he? You meet God in doing the deed of this moment in front of you. Never withdraw from it.’ ”

The podcast is available at: ‘I wanted a faith that was deeper’: Jesuit priest and Zen master

Beginner instruction will be given during the first sitting period. Roshi will then speak and take questions from the group as a whole rather than the usual daisan (individual meetings with the teacher).

More information on this branch of interfaith Zen meditation is available at kennedyzen.org.

Sheila Ross, Facilitator, Fordham Interfaith Zen