As U.S. Special Envoy to Northern Ireland for Economic Affairs, Kennedy is working to promote peace, prosperity, and stability throughout the region. Before assuming this role in 2022, he was a four-term member of Congress who represented the 4th Congressional District in his home state of Massachusetts.

As U.S. Special Envoy to Northern Ireland for Economic Affairs, Kennedy is working to promote peace, prosperity, and stability throughout the region. Before assuming this role in 2022, he was a four-term member of Congress who represented the 4th Congressional District in his home state of Massachusetts.

He is also a grandson of Robert F. Kennedy, who once famously urged Fordham graduates to be agents of good in a world “aflame with the desires and hatreds of multitudes” during his own commencement address at the University, in 1967, when he was a U.S. senator from New York.

“I’m excited and grateful that we’ll be hearing from Joe Kennedy as we celebrate our graduates on May 18,” said Tania Tetlow, president of Fordham University. “His work in Northern Ireland points to an important truth about our bitterly divided times. The process of achieving peace and stability in this region offers hope for defusing even the most intractable conflicts, and we commend him for his efforts to sustain this progress.”

Tetlow noted how Kennedy’s career echoes the intentions behind the founding of Fordham. Archbishop John Hughes—who was Irish American, like the Kennedy family—established Fordham in 1841 as part of his efforts to create opportunity for struggling immigrants from the Emerald Isle. “The experience of the Irish, in their homeland and in America, has special resonance for us at Fordham,” she said.

A Career of Service

Kennedy graduated from Stanford University and Harvard Law School, spent two years in the Peace Corps, and worked as an Assistant District Attorney in Massachusetts before winning election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 2012. In Congress, Kennedy “built an impressive legislative record around economic policy, health care, and civil rights,” according to the U.S. State Department website.

Kennedy also serves as President of the nonprofit Citizens Energy, which meets low-income families’ energy needs, and is the founder of Groundwork Project, an advocacy group that supports community organizing in historically disenfranchised areas. He is a board member of the Woodwell Climate Research Center, the Edward M. Kennedy Institute, Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights, Harvard Institute of Politics, and the Massachusetts Association of Mental Health.

On May 18, he will become the fifth Kennedy to receive an honorary degree from Fordham. His grandfather received one in 1961, when he was U.S. Attorney General, six years before giving his commencement address. His great-uncle John F. Kennedy received an honorary degree at a Fordham Law Alumni Association luncheon in 1958 as a U.S. senator, two years before being elected president of the United States. His great-uncle Ted Kennedy, a U.S. senator from Massachusetts, received an honorary degree and delivered the commencement address in June 1969. And his great-aunt Jean Kennedy Smith, U.S. ambassador to Ireland from 1993 to 1998, received an honorary degree at Fordham’s commencement in 1995, when the speaker was Mary Robinson, president of Ireland at the time.

Two other members of the Kennedy family received honorary doctorates from Fordham and delivered a commencement address at Rose Hill: Special Olympics chairman Timothy Shriver, Ph.D., in 2019, and his father, Sargent Shriver, the first leader of the Peace Corps, in 1963.

In announcing Joe Kennedy’s appointment as U.S. Special Envoy, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony J. Blinken noted the United States’ commitment to supporting “the peace dividends of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement,” referring to the 1998 accords that largely ended the political violence in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles.

“Joe has dedicated his career to public service,” and “he will draw from his extensive experience to support economic growth in Northern Ireland and to deepen U.S. engagement with all communities,” Blinken said.

The 2017 departure of the United Kingdom—which includes Northern Ireland—from the European Union has led to trade and border disputes with the Irish Republic, as well as calls for reunification of Ireland.

Speaking last year in Belfast, Northern Ireland, at a conference marking the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, Kennedy noted the importance of overcoming divisions and building shared prosperity.

“If there’s a place on this planet that is resilient, that is capable, that is clear-eyed and scrappy enough to take on this challenge, it is the shores we stand on today,” he said. “You have wrestled through hundreds of years of division, tribe and tradition, country and creed, pain, hurt, and loss, and you are still here. You are building a Northern Ireland where the troubles of the past give way to the triumphs of tomorrow.”

]]>

HARRY S. TRUMAN

Before addressing the Fordham community, President Truman rang the Victory Bell (above) outside the Rose Hill Gymnasium. The bell was salvaged from the Japanese aircraft carrier Junyo and presented to Fordham by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz as a memorial to “Our Dear Young Dead of World War II.”

Before addressing the Fordham community, President Truman rang the Victory Bell (above) outside the Rose Hill Gymnasium. The bell was salvaged from the Japanese aircraft carrier Junyo and presented to Fordham by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz as a memorial to “Our Dear Young Dead of World War II.”

“Fellow alumni and friends, it is very gratifying to be here at Fordham University in New York on the 100th anniversary of the granting of the charter to this great institution of higher learning,” he said.

FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT

Smiles abounded when FDR, the first sitting U.S. president to visit Fordham, rode up to the steps of Keating Hall with Father Gannon (center) at his side on Oct. 28, 1940, one week before he was elected to a third term as president. The event turned serious, however, when Roosevelt reviewed Fordham’s ROTC regiment. Earlier that day, Italy had invaded Greece. In little more than a year, the United States would enter World War II.

Smiles abounded when FDR, the first sitting U.S. president to visit Fordham, rode up to the steps of Keating Hall with Father Gannon (center) at his side on Oct. 28, 1940, one week before he was elected to a third term as president. The event turned serious, however, when Roosevelt reviewed Fordham’s ROTC regiment. Earlier that day, Italy had invaded Greece. In little more than a year, the United States would enter World War II.

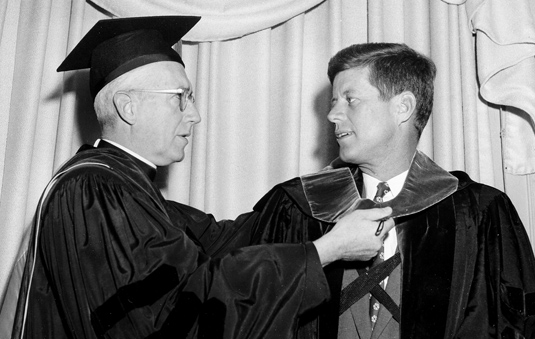

JOHN F. KENNEDY

“As your newest alumnus, I wish to deny emphatically that I have any presidential aspirations—with respect to the Fordham Alumni Association,” Kennedy quipped.

Laurence J. McGinley, S.J., president of Fordham, presented then-Senator Kennedy with an honorary degree at the Fordham Law Alumni Association luncheon on Feb. 15, 1958. Kennedy said he was honored to become an alumnus of an institution that has “never maintained its neutrality in moments of great moral crisis.”

MARY ROBINSON

The woman who preceded Mary McAleese as president of Ireland received an honorary degree from Fordham and delivered the keynote address at the University’s 155th Commencement in May 1995.

PAUL MAGLOIRE

After receiving an honorary degree from Fordham in February 1955, the president of Haiti (center) paid tribute to the University for “the citizens you are forming intellectually and morally, who will put to the service of all humanity the solid knowledge they have acquired within these walls.”

LEONEL FERNÁNDEZ

The president of the Dominican Republic (center) visited Fordham in September 2008. He told the 500-plus members of the University community who filled Keating First Auditorium that he wants to make his country a model of democracy in the Latin American world.

The president of the Dominican Republic (center) visited Fordham in September 2008. He told the 500-plus members of the University community who filled Keating First Auditorium that he wants to make his country a model of democracy in the Latin American world.

MANUEL PRADO, president of Peru, expressed his gratitude via telegram after visiting Fordham in May 1942.

LÉOPOLD SENGHOR

The first president of Senegal (right) was one of Africa’s seminal statesmen, a respected poet, professor, and intellectual. He visited Fordham in November 1961.

CORAZON AQUINO

When the president of the Philippines (left) visited Fordham in September 1986, soon after leading the nonviolent People Power Revolution that restored democracy in her country, an estimated 5,000 Filipino Americans came to Rose Hill to hear her speak. “I wish to thank you,” she said, “for being a part of People Power and Prayer Power, even though you were 10,000 miles away.”

When the president of the Philippines (left) visited Fordham in September 1986, soon after leading the nonviolent People Power Revolution that restored democracy in her country, an estimated 5,000 Filipino Americans came to Rose Hill to hear her speak. “I wish to thank you,” she said, “for being a part of People Power and Prayer Power, even though you were 10,000 miles away.”

]]>

Photo by Ken Levinson

Q&A: Dean Michael Latham, Fordham College at Rose Hill

Michael Latham, Ph.D., dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill and professor of history, is the author ofThe Right Kind of Revolution: Modernization, Development, and U.S. Foreign Policy from the Cold War to the Present (Cornell University Press, 2011) and Modernization as Ideology: American Social Science and “Nation Building” in the Kennedy Era(University of North Carolina Press, 2000). Latham spoke with Inside Fordham about the John F. Kennedy presidency, reflecting on the upcoming 50th anniversary of the JFK assassination.

Q. What was the vision that enabled Kennedy to win the 1960 presidential election?

A. It’s important to remember that he came into office following a very narrow election; he barely squeaked by. As a Catholic, he was an outsider in some ways, but coming from Harvard certainly helped him. He was also a comparatively inexperienced politician, although he was well connected among American intellectuals and strategic thinkers.

Regarding foreign policy, he was very much a creature of the Cold War, and subscribed to its ideological constructs, including the imperative of global containment and the domino theory. If you read his inaugural address, what you see is not only a soaring idealism and inspiration but a determination to, as he put it, let every nation know “whether it wishes us well or ill, we will pay any price, we will bear any burden in the defense of freedom”—making it clear to any adversary that the United States would not fail in this obligation. If you look at the Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba, he didn’t ask the tough questions. He took the advice and guidance of the CIA and Defense Department officials who were convinced that they could remove Fidel Castro, and things went badly wrong.

But you also see a president who learns from these mistakes. You could argue that his worst failures and his greatest accomplishments were both in foreign policy. The Bay of Pigs was a complete disaster; on the other hand, his management of the Cuban missile crisis paints a different picture. Despite tremendous pressure from the military for a more aggressive response, he instead tried to slow the crisis down, and in doing so he opened the space for a diplomatic solution. That was a significant step.

Q. Did serving in the office alter Kennedy’s vision?

A. By 1963, Kennedy was actually starting to make an overture to the Soviets. He made a famous speech in August of ’63 where he began talking about “making the world safe for diversity,” including the co-existence with the Soviets, and a tolerance for the nationalism of newly emerging countries. He slowly began to question the limits of an ideologically driven vision of the Cold War.

He also shifted on civil rights. Kennedy did not want to become involved in the civil rights struggle, especially not in a first term. But in April of 1963, when Martin Luther King and others went to Birmingham and segregationist violence erupted, and the nation witnessed children being hit by fire-hose water strong enough to take the bark off of tree trunks, Kennedy realized he had to engage. And so he went on national television and declared that this was fundamentally a moral question. “It’s as old as the scriptures, it’s as clear as the U.S. Constitution.” Once he did that, he took civil rights out of the realm of political compromise and infinitely deferred negotiation and he elevated it to a matter of principle. You don’t call something a moral question if you are about to cut a piecemeal deal on it. That was a pivotal moment.

Q. The assassination on Nov. 22, 1963, less than three years into his presidency, shocked the nation. How did America and beyond grapple with such a loss, much of it televised?

A. Certainly those tragic images were devastating. There was tremendous sorrow. Many around the world saw him as someone with potential who was capable of shifting away from some of the older ways of thinking about American power. Kennedy was viewed and respected by people like [Jawaharlal] Nehru, by other leaders around the world—in Latin America, for example—as somebody who understood that nationalism, and the desire for these counties to find their own way in the world, was something that had to be taken seriously. With the assassination, Kennedy came to embody the symbol of idealism lost, or betrayed.

Q. With his death, was sixties idealism really lost or betrayed?

A. For some people that outlook changed. To be honest I am not sure it changed the overall direction of American [foreign]policy. I don’t think Kennedy was about to walk out of Vietnam. I don’t see him escaping the mistakes that [Lyndon] Johnson ultimately made there. Historians disagree on this, by the way.

What I do see is a growing recognition on the part of the Democratic Party that some fundamental questions—about inequality, about injustice, about the nature of civil rights—had to be addressed.Lyndon Johnson’s presidency is in many ways the amplification of these trends. Johnson marched into Vietnam wholeheartedly. At the same time,he launched his Great Society program and a determined campaign for civil rights.

One could argue that the seeds of these were ultimately planted in the turn that Kennedy began to make. And Johnson made the most of this by talking about Kennedy’s legacy.

While still caught in the Cold War, Americans were recognizing that these fundamental structural injustices had to be dealt with.

I think that, for all of the mistakes he made, Kennedy captured a certain idealistic moment. [And] it was quite awfully the beginning of a chain of devastating assassinations, be it John Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy, or Martin Luther King, Jr., which seemed to steal the promise of something much, much better.

Q. Do you see parallels between Kennedy and President Obama?

A. There are a lot of parallels. Both entered the White House comparatively young, comparatively inexperienced politically, remarkably articulate and eloquent, capable of inspiring large numbers of people, running on the campaign of change. Obama was not the first person to [talk]about hope and change. Kennedy was talking about the same thing, about a departure from the Eisenhower conservatism, about a version of liberalism in which citizens will be made more active and can pursue these sorts of idealist goals. And yet they are both limited by serious constraints, and they both learn in the process.

The difference is that we will have the full legacy of Obama to evaluate. With Kennedy we are always left with that question of what might have been.

(Interview conducted by Joanna Klimaski and Janet Sassi.)

JFK’s Legacy

Visit soundcloud.com/fordhamnotes/fordhams-michael-latham-on-jfk for interview highlights.

The Kennedys: America’s Emerald Kings, written and directed by filmmaker Robert Kline, is based on the acclaimed book by Thomas Maier (FCRH ’78). The screening will be held at 7 p.m. at the McNally Amphitheatre and will be followed by a discussion with both Maier and Kline.

Maier’s book, which has the same title as the documentary, was published in 2004 by Basic Books. It traces the journey of five generations of Kennedys from County Wexford, Ireland to the United States and into the 21st century. The book is being re-issued with a new introduction about Sen. Ted Kennedy’s health crisis and the impact of the Kennedy political legacy on Barack Obama and the 2008 campaign.

Kline’s documentary will feature private footage of the Kennedys. Kline is the executive producer of Enduring Freedoms Productions and the former executive vice president of 20th Century Fox. The documentary will be distributed and sold nationally by Warner Brothers on Nov. 11 as a three-disc package that includes Oliver Stone’s JFK, three hours of bonus content and collectible memorabilia.

The event is co-sponsored by Fordham University, the Institute of Irish Studies and Warner Home Video. For more information or to RSVP, contact Krystyna Davenport at [email protected] or (212) 636-6575.

]]>