The award, which was given at the conclusion of the Penn Mutual Collegiate Rugby Championship, was presented to Puccia during an on-field ceremony at the Talen Energy Stadium in Chester, Pennsylvania, by Penn Mutual CEO Eileen McDonnell and Joe Jordan, GABELLI ’74.

As part of the award, Puccia received a $5,000 contribution to a charity of his choice. He’s chosen to donate to the Tundra Women’s Coalition, which works to protect women and their children in Alaska from drug and alcohol abuse related domestic violence. Fordham’s rugby program also received $1,000 in Rhino rugby gear.

Jordan, a member of the Fordham Ram’s Hall of Fame, conceived of the award as a way to highlight the lessons of his book Living a Life of Significance (Acanthus Publishing, 2013), which has been translated in five languages and emphasizes living a purpose-driven life in the service of others.

Puccia, an Italian studies/history double major from Whitestone, Queens, is the the recipient of the Thomas M. Lamberti Endowed Scholarship Fund, which is endowed by Tom Lamberti, FCRH ’52, and his wife Eileen Lamberti, and is designated for a Fordham student who is a graduate of Xavier High School. He is also a member of the Fordham Men’s Rugby Club. He took to rugby as first-year student, and impressed the award judges through his dedication to multiple causes.

Last year, he traveled to Bethel, Alaska, as a member of Fordham’s Global Outreach Program to work with groups such as the Tundra Women’s Coalition. He volunteered last summer with the Queens District Attorney’s domestic violence bureau. This summer, he’s volunteering at the Urban Justice Center’s Veterans Advocacy Project, which provides pro-bono work for veterans in need throughout New York City.

The award, for which he beat out 19 other nominees, was humbling, he said.

“The work has just felt like the right thing to do, but to get recognized for it was a nice chance to be retrospective. I’d never sat down and been like ‘I’ve done good,’” he said, noting that he’s been involved in service projects since his first years at Xavier High School, which like Fordham is affiliated with the Society of Jesus.

“It was a nice chance to sit down and recognize what I’ve done, and not necessarily celebrate it, but to be grateful for the opportunities I’ve had.”

As the creator of the award, Jordan had a role in choosing the winner, but said he deliberately held back from awarding Puccia the highest number of points he could so as not to seen to be favoring someone from his alma mater. The fact that Puccia won anyway was testament to his character, he said.

“What really distinguishes him is his doing multiple things. Some people are doing spectacular things, but just one,” he said, noting that Puccia has found time in his busy student-athlete schedule to be involved in a variety of causes. “When does this guy get it done?” he asked.

Jordan, who found success upon graduation in the insurance industry and was most recently a senior vice president of Met Life, played rugby recreationally for 30 years after playing football for Fordham. He’s been a steadfast donor to Fordham’s athletics programs.

He convinced McDonnell to support the Penn Mutual rugby tournament as a way to connect with younger people and show them how a career in the financial services sector can be compatible with living a purpose-filled life.

He grew up around the corner from the Rose Hill campus, so being able to honor another native New Yorker with this award made this even more resonant, he said.

“This is like something out of The Bells of St. Mary’s or It’s a Wonderful Life: Two kids growing up in New York City, with a Jesuit connection, doing good stuff,” he said.

Puccia never played rugby in high school, but he was convinced by two fellow classmates from Xavier who enrolled at Fordham a year before him to join. The game is fun, he said, but what really appeals to him is the camaraderie between teammates and alumni who return to campus to watch matches.

“That energy that the game attracts isn’t only applicable to what they do on the field, they apply it to everything they do. They help each other out. I tutor Italian, and I know another who tutors in biology,” he said.

“It’s a very strong group, and they put their best efforts into everything they do.”

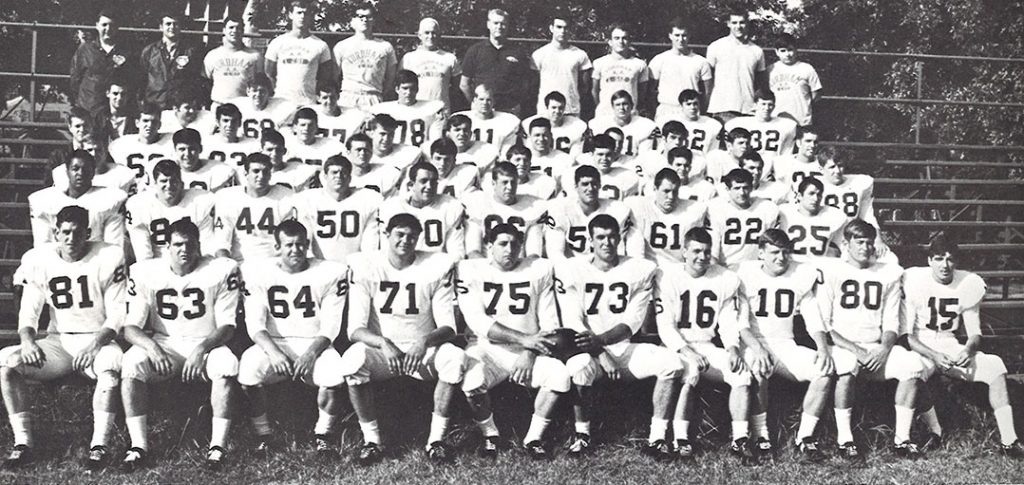

]]>It was 50 years ago that Zizzo helped lead the Fordham club football team to a national championship as co-captain, helping revive a sport that was a Fordham hallmark in the days of Vince Lombardi and the Seven Blocks of Granite but that had been absent at Fordham from 1954 to 1964. The 1968 club team’s victory gave Fordham football a brighter future—contributing to the University’s decision to bring back the sport at a varsity level in 1970 and laying the groundwork for more recent successes, including a Patriot League title in 2014.

At the annual Football Dinner in the week leading up to Homecoming on September 22, Fordham will be honoring the 1968 team. At least 35 of the 40 surviving team members are planning to attend.

“Keeping the team together has been a big thing in my life,” says Zizzo, a member of Fordham’s Board of Trustees since 2013. “It sounds strange, but I feel an obligation to do it, but I also want to do it. The striving together and relying on one another as a team has kept us together for so many years, so this is a great thing for us.”

Zizzo attributes the team’s triumphs and enduring camaraderie to their ability to rely on each other and put the Rams’ success over any one player’s individual ego. “No matter how good you are,” he says, “your team cannot excel unless the other players are excelling at the same time.”

In some ways, Zizzo says, those team dynamics reflect the strengths of Fordham’s rigorous Jesuit education, which, he says, “is about expanding your horizons and realizing there’s a whole world you have to be responsive to, that when you act, you act not only for yourself but on the basis of all humanity, to help others. You can’t be isolated and looking only to yourself.”

These are lessons that Zizzo, a retired real estate attorney, says served him well in life and in his profession. “You have to be able to work together as a group,” he says. “Everybody always asks how we should divide the pie up. But the better question is how do we grow the pie? It’s the growing of the pie that leads to bigger success, and you can’t do that with one individual’s effort.”

Last year, Zizzo joined forces with John Costantino, GABELLI ’67, LAW ’70, and John Lumelleau, FCRH ’74, to launch the ongoing Football Office Challenge to help raise funds for the renovation of the Fordham football offices. “The new offices will help recruiting and the operation, experience, and success of the current team,” he explains. “And the team’s success could enhance the face of Fordham to the rest of the world.”

It’s that larger goal that has driven him to not only stay involved with Fordham football but to continue participating in other alumni activities, like his trip to the Dordogne region of France with the Alumni Travel Program a few years ago.

“I mean, I enjoy the game and want to see football excel,” Zizzo says. “But the larger importance of football is to support the identity of Fordham and help people realize that Fordham is an important place to be.”

Fordham Five

What are you most passionate about?

Other than the health, well-being, and happiness of my family (which is by far the most important thing in my life), my most passionate goal is to see Fordham University climb to the prominence it deserves—that is, to be considered one of the best universities in the country. As a relatively poor person from a relatively poor family who received a scholarship from Fordham, I appreciate that Fordham has done more than any prominent university I know to pursue its mission to educate all levels of our society in the intellectual rigors of the Jesuit tradition with a focus on the highest human values.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

There are two pieces of advice that have helped me lead my life and helped me professionally. First, my immediate family impressed upon me the importance of working as hard as I could in everything I did. Second, two of my professional mentors showed me through both their words and actions that being honest and never lying would lead me to a successful and rewarding career.

What’s your favorite place in New York City? In the world?

By far the most incredible place in New York City is Greenwich Village. The vibe is tremendous: winding tree-lined streets, a diverse population, local theater productions, other cultural amenities, incredible restaurants and shops. To me, it’s the greatest area in the greatest city in the world. Maybe because it resembles New York City so much, Rome is my favorite city in the world. It has many of the great qualities of New York with two big pluses: First, Roman traditions and philosophy are prominent in Western history and are ingrained in many of us. Second, the people of Rome are as warm and welcoming as any I have encountered.

Name a book has had a lasting influence on you.

Atlas Shrugged has made a lasting impression on me. I have read it twice: once as a relatively young adult and again about 15 years ago. The basic principle of the book is that people must be given the incentive of possible profit and success in order to reap the rewards of the world and to help protect and support the family; I have many examples of this being true. I believe the book also makes it clear that the drive to success and security does not necessarily interfere with a person’s desire to help others, especially those that are willing to contribute to society or those who are not able to work.

Who is the Fordham grad or professor you admire most?

I have nothing but admiration for Joseph Cammarosano [professor emeritus of economics]. He has the unique ability to be helpful and warm, and he is a professional educator who is both an intellectual and a leader. I remember him as a great teacher and a great source of knowledge. He also greatly contributed to the University in two ways: His even personality and desire to help Fordham made him excellent at being a practical and successful liaison between the administration and the faculty in the 1960s, and in helping Fordham overcome financial struggles in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

]]>

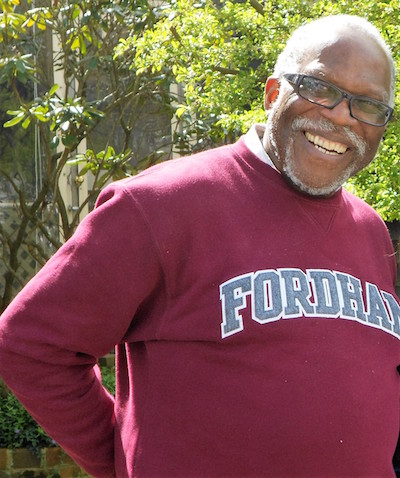

As a school administrator for nearly four decades, Peter E. Carter, FCRH ’65, faced some turbulent times and challenging situations: court-ordered busing, school district takeovers, and seemingly impossible financial crises. When he reflects on the confidence he needed to be successful, he often recalls his Jesuit education at Fordham. “We did all the things that prepared you for leadership without even knowing it,” he says. When a supervisor once denied him a promotion early in his career, he swiftly moved on. “He didn’t know I went to a Jesuit college,” Carter says, “where the next step is the next step up!”

As a school administrator for nearly four decades, Peter E. Carter, FCRH ’65, faced some turbulent times and challenging situations: court-ordered busing, school district takeovers, and seemingly impossible financial crises. When he reflects on the confidence he needed to be successful, he often recalls his Jesuit education at Fordham. “We did all the things that prepared you for leadership without even knowing it,” he says. When a supervisor once denied him a promotion early in his career, he swiftly moved on. “He didn’t know I went to a Jesuit college,” Carter says, “where the next step is the next step up!”

Carter spoke with FORDHAM magazine about his time at WFUV, Fordham’s radio station; his experience as one of very few black men on campus during the early 1960s; his eventful career; and his ill-fated judgment call regarding four mop-topped blokes from Liverpool.

As a Brooklyn boy, how did you choose Fordham?

Fordham was chosen for me. I went to Regis High School in Manhattan, an all-boys Jesuit school. The principal insisted students apply for Catholic universities. I was accepted at Fordham and offered a full four-year scholarship. As a poor kid of a single mother from low-income housing projects in Brooklyn, I certainly had to take that offer. I wasn’t given room and board, so my mother said, “We’ll move to the Bronx!” So I was a day hop. I majored in classical languages—Latin and Greek.

And you ran for student government?

In freshman year I boldly ran for student council office. I was vice president of the freshman class. I had what we called “the Regis vote.” In sophomore year I was treasurer, and I was in charge of funding for the concert committee [which arranged to bring musical acts to campus.] Our concerts included the Kingston Trio, Ray Charles, and Peter, Paul and Mary—my favorite. Our class started that committee—or at least formalized it.

You became sports director at WFUV. What was it like in those days?

I joined WFUV in my sophomore year. There was an opening right away in sports, and I just slid into doing play-by-play for Fordham basketball and baseball. I later became sports director.

WFUV was on the third floor of Keating Hall at the time. There was a studio, a half office for the station manager, two turntables in the engineer’s booth, and a record library behind the booth. That was it. We were all student volunteers. It was comfortable. You could bring your books and study.

I did a segment called Around the Town about things to see and do in New York City. I covered the Beatles coming to Carnegie Hall in February 1964, [three days after their famous Ed Sullivan appearance]. I captured the excitement and the screaming young ladies.

Working with the concert committee, had you heard of the Beatles before they came to the U.S.?

In early 1963, the concert committee had gotten wind of this group from Liverpool called the Beatles. Someone said, “Let’s fly them in to the Fordham Gym and have them do a concert.” As the money guy, I was skeptical. I said, “What? The Beatles? What are they, some kind of insects? We’ll lose our shirts!” So I said no.

So when people say, what was the worst decision you ever made—that was the worst decision I ever made in my life. Fordham could have been the first place the Beatles ever appeared in the United States if not for Peter Carter.

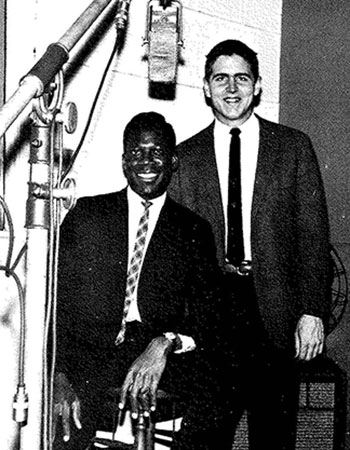

As sports director at WFUV, you covered the return of Fordham football in 1964. What do you remember from that broadcast?

The highlight of our class, the Class of ’65, was that it was the one that brought football back to Fordham [as a club team]. This was a total student-run operation.

Our first home game was against NYU. We broadcasted it on FUV. We had to get a telephone line so we could hook it up to our tower at Keating Hall. Then I had to figure out how was I going to get on-field interviews. With microphone wire in hand, I crawled under the stands, which had been built by students, to have a microphone in place on the field. I did those interviews personally. Not everyone could buy a ticket, but people tuned in to 90.7 for a very live broadcast. And Fordham was victorious.

You were one of very few African-American students on campus at the time. What was that like for you and your classmates?

I was one of seven African-American students—or as they called us then, Negroes—out of 2,000 undergraduate students at Fordham College. I had to learn how to navigate around human beings who, through no fault of their own, had never met anyone like me. Their view of black people was from television. Or from watching black athletes. I chose not to be an athlete. I became a campus politician. It was an all-white campus, and I’m a campus politician. And the radio station sports director. [It was] a world that these guys kinda had to get used to. They liked and respected me. We all learned something about one another, which made us better off.

What was it like starting out as a teacher in New York City?

I wanted to give back to the Jesuits what they gave me, so I taught Latin and Greek for a few years at Brooklyn Prep [a Jesuit high school that closed in 1972]. Then the diocese opened an alternative school [for troubled students] called the New High School. I was maybe 26, and they asked me to be assistant principal. We did the best we could to help those kids grow, even though circumstances put them in a position where the world looked at them askance.

What were some of the greatest challenges of your career?

In 1975 I became principal of a middle school in New Castle, Delaware, that was educating 1,300 kids in a space with 986 capacity. I always remember that number—986. We turned that school around. The courts had just ordered the schools to be desegregated and we bused in black students from Wilmington. That was quite a challenge. They weren’t warmly received and they were scared. We worked very nicely—had a lot of social events and such—and soon they weren’t scared anymore.

Later, as Essex County superintendent of schools in New Jersey in 1989, I was responsible for 23 school districts, including Newark, which [the state] eventually took over because they weren’t able to get the job done. I helped lead that process. No one was happy and no one was pleasant. However, the important part is, we helped the kids.

The biggest challenge I had was in 1995, as superintendent of schools in Irvington, New Jersey. When I came, the district had a $9 million deficit. After four years, I left it with a $3 million surplus. I persuaded the entire staff, including myself, to take a one-year salary freeze. One time I had 24 hours to make a payment of half a million dollars to the insurance company or they were going to cut benefits to the entire staff. Using my persuasive skills—learned in part at Rose Hill—I got an advance in state aid and made the payment in time. That was the greatest challenge of my career and perhaps my greatest accomplishment. We can balance that out with the Beatles fiasco.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Nicole LaRosa.

]]>

In The Gamble, his 2009 book on the Iraq War, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Thomas Ricks described Jack Keane, a retired four-star general, as “crackerjack smart and extremely articulate, often in a blunt way. Most importantly … he is an independent and clear thinker.”

Keane began his military career at Fordham as a cadet in the University’s ROTC program. He graduated in 1966 with a bachelor’s degree in accounting and went on to serve as a platoon leader and company commander during the Vietnam War, where he was decorated for valor. A career paratrooper, he rose to command the 101st Airborne Division and the 18th Airborne Corps before he was named vice chief of staff of the Army in 1999.

Since retiring from the military in 2003, Keane has been an influential adviser, often testifying before Congress on matters of foreign policy and national security. In late 2006 and in 2007, he was a key architect of the surge strategy that changed the way the U.S. fought the war in Iraq. He is a trustee fellow at Fordham; a member of the board of directors of General Dynamics, an aerospace and defense company; and chairman of the board of the Institute for the Study of War, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank that monitors global conflicts. He’s also a senior national security analyst on Fox News.

Keane spoke with FORDHAM magazine about service, leadership, and whether or not his loyalties will be divided on Sept. 1, when Fordham football opens its 2017 season with a game against Army at West Point.

What inspired you to join the Army?

I joined the ROTC program essentially because the country was at war and we knew that we would likely be joining it. In the mind of myself and my friends, it made sense to do that as officers, although none of us had ever had a family member who was an officer. Then, as part of the ROTC program, I joined the Pershing Rifles [national military society] because they seemed more confident and accomplished than the other participants in ROTC.

We took basic marksmanship training, and we would go to Camp Smith and practice patrolling techniques and other tactics under the supervision of active-duty officers. That gave me some exposure to what I thought the Army would be like. By the time I graduated, I came to recognize that I had an aptitude for it. And I liked the idea of serving the country.

I saw an interview you did a few years ago with Bill Kristol. You told him about a conversation you had with a Jesuit around the time you were graduating from Fordham. Who was that Jesuit and what did you two talk about?

I think it was Father [Thomas] Doyle, [then an assistant professor of philosophy], but I’m not sure. He asked me what I was planning to do, and I said, “I’m going to go in the Army.” He said, “No, I mean, after the Army.” I said, “Well, I’m thinking about maybe making a career out of it if I’m capable and if I like it to the degree that I think I will.” He said, “Why would you do that? You have so much more to offer.”

I said, “Well, Father, have you ever been associated with the Army? Were you a chaplain?” He said no. I said, “Well, I’ve spent a lot of time around it and people who serve in it, and I don’t think it’s necessarily what you think it is. I think there’s an incredible amount of opportunity for growth and development as a human being. I think I’ll have the freedom of thought and the opportunity to be very challenged, and I think that will lead to a growth experience for me.”

That turned out to be the case.

The way you describe the Army, in terms of opportunities for growth within a strict organizational structure, could also be applied to the Jesuits, I would think. You went to Catholic schools before Fordham, but was Fordham your first encounter with the Jesuits?

I told my new Army friends that after 16 years of Catholic education, the transition to the Army was very smooth! I think of Fordham and the Jesuits as a transformational experience. The rigor of the Jesuit methodology was evident in all classes. What they were least interested in is regurgitation of information. What they’re most interested in is critical thinking based on analysis and some rigorous method of interpretation using reasoning.

That was challenging because it was completely different than my Catholic high school. I thought college was just going to be high school on steroids. At Fordham, it was quite something else. The whole learning process was about your own growth and development as a human being—not just intellectually but also morally and emotionally. I don’t think I would have been as successful as a military officer if my path didn’t go through Fordham University.

Would you talk about your approach to leadership and how it has evolved since your days as a platoon leader? Are there certain qualities that you feel all effective leaders share?

First of all, there are very few natural-born gifted leaders. Most leaders learn from experience. If you’re in the United States military and you start out as a second lieutenant platoon leader with 40 people, your life from that moment on is a leadership laboratory. You have plenty of opportunity to learn and also to observe leaders who are very effective.

When you really get down to it, what you’re doing is motivating and inspiring others to reach their full potential and to do that collectively as an organization. Whether it’s a small team or a large team, the opportunity to learn and to grow is really quite extraordinary.

Some of that for me was in combat, which is such an extraordinary human experience. Everything that you are as a person—your character, your intellect, your moral and physical courage—is brought to bear under significant stress. People’s lives are dependent on you. You’re not only there to protect the civilian population and protect your own soldiers; you’ve been given the authority to take lives. The moral underpinning for something like that is really quite significant. I think having had 16 years of Catholic education and participating at Fordham, where I took four years of theology and four years of philosophy, which were my favorite courses, by the way, really provided me with the wherewithal not only to cope with combat but to perform to a high standard.

With regard to leadership, anybody can make a list of attributes leaders have to have—integrity, judgment, moral underpinning, et cetera. But there is one attribute that’s always stood out for me, and that’s perseverance. You have to persevere to accomplish the mission. Whether that’s in a stressful situation like combat or in other environments, perseverance really can be very defining because there are constant impediments and obstacles. You see people, not just in the military but in all walks of life, who because of those obstacles and impediments accept something less. They could continue to drive on. Most of the time, it’s more about mental toughness than it is about physical toughness.

Two years ago, Fordham ROTC established the General Jack Keane Outstanding Leader Award, to be given each year to a graduating cadet. What does that award mean to you, and what advice do you give newly commissioned officers?

I was honored to give out the first General Jack Keane Award [at the University Church in 2015]. And I was quite humbled by it, to be frank, when I got my head around the fact that they will always give this award to somebody who is outstanding as a cadet and likely more outstanding than I was.

I’ve always told my officers and my generals that we’re in leadership positions because we know how to lead effective organizations; we get results. But our legacy is not how well we run these organizations, because there’s another guy or gal standing behind us who could run it even better. The real legacy is the growth and development of the people in these organizations. If you focus on their growth and development, and if you have programs that support that, the organization will take care of itself. The organization will actually blossom because the people in it are so committed to it and have a very high degree of satisfaction. That is your legacy.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

It came from a sergeant major. I was a major at the time. I was very intense, working very hard, and I was a little frustrated with my boss, my battalion commander, who wasn’t paying attention to all the things I thought he should be paying attention to. The sergeant major closed my office door and said to me, “Major, I know you’ve got some things that are bothering you. I want you to know just one thing: You’re responsible for your own morale.” He looked at me and said, “You got it, sir?” I said, “I got it, sergeant major, thank you very much.”

I never forgot that. It was sound advice.

Fordham football is playing Army at West Point on September first. Who will you be rooting for?

I’m going to miss the game, unfortunately, but good Lord, I want to beat those guys. When I go to West Point for the game, I usually talk to the corps of cadets about the U.S. global security challenges: the Middle East, Russia, the problems with Al Qaeda and ISIS, et cetera. After I spoke a couple of years ago, the first question I got was from a cadet. He said, “General, so we understand you went to Fordham University. You spent almost 40 years in the Army, and you spent only four years at Fordham, so I’m assuming you’re rooting for Army.”

He was just having fun with me, but I looked at him. I said, “Are you kidding me? You know damn well who I’m rooting for tomorrow, OK? I’m rooting for my alma mater.”

So yes, I want both teams to play well, certainly, but I definitely want us to win.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Ryan Stellabotte.

]]>

President Barack Obama has named former federal judge Arthur J. Gonzalez, GABELLI ’69, LAW ’82, to the oversight board created by Congress to address the economic crisis in Puerto Rico, the White House has announced.

Gonzalez, a senior fellow at the New York University School of Law and former chief judge of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York, is one of seven people appointed to the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico. The board was created on June 30 to restore economic opportunity in Puerto Rico by helping the U.S. territory restructure its debt and control spending.

Gonzalez grew up in Brooklyn, earned a degree in accounting from Fordham, and worked as a New York City public school teacher for 13 years before earning his Fordham law degree in 1982.

After serving in the IRS Office of Chief Counsel and working in private practice, he started his 17 years of service as a bankruptcy judge in 1995. He handled some of the nation’s largest and most high-profile bankruptcy cases, including those of Enron, WorldCom, and Chrysler, and was awarded the Medal of Achievement from the Fordham Law Alumni Association in 2012.

In a 2007 profile in FORDHAM magazine, he credited Fordham’s Jesuit tradition for the role it played in his career success. “Jesuit education encourages thinking, analysis, and generally provides a good foundation for understanding the subject matter while encouraging a commitment to community and service,” he said.

]]>

Between his time in the Army and his banking career, Calero has worked all over the country and the world. But he never lost sight of the Jesuit principles he grew up on.

“I remained somewhat idealistic about what you can do in life,” he says. “I felt banking could be changed to meet the needs of everyone, not just a subset.”

As president and CEO of TIAA-CREF Trust Co. FSB, Calero has been tasked with creating a bank for teachers, academic communities, hospitals, and other service-oriented professionals, offering mortgages and additional products to help them meet their financial needs. “This is really about helping the difference makers,” he says.

That sense of nobility Calero brings to his work is something he encountered both in the military and in his Jesuit education at Fordham.

“There’s just a value system in both,” he says, whether that system is based on the teachings of Jesus Christ or the U.S. Constitution. “There is a cause greater than yourself,” he adds, noting the “values of courage and selfless service that don’t always exist elsewhere.”

Three years into his first contract with the Army, Calero applied for an ROTC scholarship. He got a call from Fordham and was soon studying economics at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, a few miles from where he grew up on 132nd and Broadway.

Calero says he’s grateful for his Fordham education, not only because of what he learned but of how he learned it.

“It’s not just learning basic skills. It really is critical thinking. Well before you learn something, I think the Jesuits teach you why you should know it,” he says. “You become a continuous learner, where you see learning all around you. It doesn’t just start or stop in the classroom. You spend your whole life learning.”

Right after his Fordham graduation, Calero entered the Army again, separating in 1997 as a captain. “I thought that was it,” he said. Then he got a letter after 9/11. He was promoted to major and sent to Pakistan for 14 months.

During his first stint in the Army in the 1980s, he deployed to Honduras after completing Special Forces training and becoming a Green Beret. It was a time when civil wars and revolution wracked that nation’s Central American neighbors. His experiences in the region played a big role, he says, in understanding the Latin American countries where he did business with Citibank in the late 1990s.

“I would go to every Latin American country and assist with business models, and you recognize that every country is different. Some just did not have a middle class. So how do you grow your business model based on the population?” he said, citing one of many challenges.

His banking career also took Calero to Texas (where his son attended a Jesuit high school), Florida, and most recently, Portland, Oregon, where he was executive vice president of community banking for Umpqua Bank. He returned to New York in 2013 with his wife, Nancy, whom he met in the sixth grade, and their three children.

Calero is one of the newest members of Fordham’s President’s Council, a group of professionals and philanthropists who are committed to mentoring Fordham students, funding key initiatives, and raising the University’s profile. Last year, he mentored a Fordham ROTC student who will be commissioned in May and will go on to active duty. He said he “wanted to do more than donate” to the University when he came back to New York because of the sense of service that Fordham helped instill in him long ago.

“Whether I was the Puerto Rican kid from the Upper West Side or the recent vet,” he says, “Fordham has just always been there.”

]]>

At Fordham, students from all three campuses gathered to listen to, discuss, and commemorate the historic visit from the first Jesuit pope.

A live viewing at the Lincoln Center campus of the pope’s address to Congress

Papal flags flew and “Pope2Congress” bingo cards were distributed on Sept 24, as members of the Fordham community gathered around televisions on all three campuses to watch Pope Francis address a joint session of the U.S. Congress.

Photo by Patrick Verel

In addition to the lobby in the McGinley Center and Room 228 at the Westchester campus, the address—the first ever for a pope—was broadcast in the plaza-level lobby at the Lincoln Center campus.

The address, in which the pope challenged U.S. leaders on issues such immigration, global climate change, and income inequality, drew both a mix of curious onlookers who lingered at the top of the escalators upon seeing the crowd, and those who listened intently to the hour-long address.

Jamie Saltamachia, FCRH ‘14, GSS ’15, assistant director of the Dorothy Day Center for Service and Justice, was excited that the pope was speaking directly to leaders whose constituents, in many cases, are poor.

“He’s really made an impact on a lot of people and really opened a lot of eyes,” she said.

“People who may have lost their faith years ago are starting to come back to the church, because he is so open minded and has a strong sense of social justice.”

Katie Svejkoski, a first-year English graduate student from St. Louis, said she was pleasantly surprised that Francis called for the abolishment of the death penalty, and was thrilled that he praised Dorothy Day.

“She’s a fabulous lady, and around here she gets lots of credit because we have the Dorothy Day Center But I don’t know that she gets credit in enough areas of the Catholic world or in America in general,” she said.John J. Shea, S.J. director for Campus Ministry at Lincoln Center, said he found the pope to be very strong in what he wanted to say without being political. And while he was particularly impressed that Francis grouped Thomas Merton with Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., and Dorothy Day as Americans worthy of emulation, he said it was amazing just to see a pope in such a setting.

“We live in interesting times. A pope would never have been invited when I was a boy in high school, when John F. Kennedy was trying to get elected, because they thought the pope would try to run America,” he said.

“Today we see that 30 percent of Congress is Roman Catholic, including the speaker of the house, as are the vice president and more than half of the Supreme Court. It’s all amazing.”

Procession through Central Park

The pope’s second day in New York began with an address to the United Nations, followed by a solemn visit the 9/11 Memorial and Museum in downtown Manhattan. Later that afternoon, the pontiff spoke to elementary school students at Our Lady Queen of Angels School in Harlem before greeting the multitude in Central Park.

At Central Park, where 80,000 New Yorkers won tickets in a lottery to the papal procession, some members of the Fordham community waited in line for nearly three hours to get into the park, as several lines snaked between 60th and 69th streets.

Photo by Janet Sassi

Once in the park, Maddy Cunningham, DSW, professor of social work at the Graduate School of Social Service, made a decision to watch the procession rather than try to photograph the pope with her phone as he passed by in his Popemobile.

“I just wanted to see him with my own eyes, to experience the moment,” said Cunningham, who still remembers seeing Pope Paul VI in a procession on Queens Boulevard as a child in 1965. “I am glad I didn’t even try to film [because]he was turned to our side, and he was waving. I now have that image in my mind’s eye.”

Noreen Rafferty, an assistant director in the office of marketing and communications, videotaped the moment when “all the hands went up.”

“It was unbelievable,” she said. “There were so many nationalities—Italian, Irish, Filipino, Puerto Rican. He’s got to come again.”

The Papal Mass at Madison Square Garden

From Central Park, Pope Francis journeyed south to Madison Square Garden, where he celebrated Mass Friday evening with more than 20,000 people.

Despite a three-hour wait and a line that stretched 20 city blocks, the atmosphere outside the arena was one of excitement and conviviality. Strangers befriended one another as they inched closer to the entrance. A group of nuns sang hymns to pass the time. One man broke from the line and ducked into a Duane Reade, returning with a case of water for the wearying pilgrims.

Photo by Joanna Mercuri

“I was thirsty, and I figured everyone else was, too,” he said as he distributed water bottles down the line.

At 6 p.m. sharp, musicians from St. Patrick’s Cathedral Choir and the New York Archdiocesan Festival Chorale began the processional hymn, and Pope Francis processed into the arena accompanied by bishops, priests, deacons, and seminarians from throughout New York State.

The 90-minute Mass was as international as the crowd itself, with the liturgy alternating between Spanish and English and prayers being offered in Gaelic, Mandarin, French, and Italian. In his homily, Pope Francis spoke in Spanish about the role of faith in cities. Big cities encompass the diversity of life, with their many cultures, languages, cuisines, traditions, and histories. Negotiating this diversity is not always easy, though, the pontiff said. Tragically, our most vibrant cities tend to hide “second-class citizens.”

“Beneath the roar of traffic, beneath the ‘rapid pace of change,’ so many faces pass by unnoticed because they have no ‘right’ to be there, no right to be part of the city,” Pope Francis said from an ambo built especially for the Mass by young men from Lincoln Hall Boys’ Haven.

“They are the foreigners, the children who go without schooling, those deprived of medical insurance, the homeless, the forgotten elderly. These people stand at the edges of our great avenues, in our streets, in deafening anonymity. They become part of an urban landscape which is more and more taken for granted, in our eyes, and especially in our hearts.”

The remedy to our “isolation and lack of concern for the lives of others” is faith, the pope said. We must heed the words of the prophet Isaiah by “learning to see” God within the city, and then go out to meet others “where they really are, not where we think they should be.”

“The people who walk, breath, and live in the midst of smog, have seen a great light, have experienced a breath of fresh air,” Pope Francis said. This light imbues us with a “liberating” hope—“A hope which is unafraid of involvement… which makes us see, even in the midst of smog, the presence of God as he continues to walk the streets of our city.”

Photo by Joanna Mercuri

As the Mass drew to a close, Archbishop of New York Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan offered words of welcome and gratitude to the Holy Father on behalf of New Yorkers.

“Every day and at every Mass, we pray for Francis our pope—and now you here you are!” Cardinal Dolan said, prompting an eruption of cheering and applause throughout the arena—the single display of ebullience amid an otherwise reverent liturgy.

“It is so dazzlingly evident this evening that the Church is our family. Thank you, Holy Father, for visiting us, your family.”

The pope offered a final blessing and before departing, delivered his familiar farewell.

“And please, I ask you—don’t forget to pray for me,” he said.

Fordham Day of Service

On Sept. 26, students and other members of the Fordham community participated in a day of service with Habitat for Humanity-Westchester in honor of the pope’s visit, said Carol Gibney, assistant director of campus ministry. More students showed up than had signed up, she said.

The students worked on refurbishing the Pope Francis house in Yonkers as well as on some other projects in the surrounding area—cleaning an abandoned lot, planting flowers, and laying a brick walkway.

Photo courtesy of Carol Gibney

“The area we worked in is one of those communities that are often plagued with violence, crime, and poverty,” said Gibney. “It is one of those communities often forgotten or discarded as ‘worthless’” that Pope Francis spoke about on his U.S. trip.

Once the South Yonkers house is completed in December, it will become the home of U.S. Army Sgt. Michael Velazquez, 24, and his family of six.

“It was a great day for our students as the idea of being men and women for others, particularly by helping to build a house for an Iraqi veteran, a house that is named after the first Jesuit Pope!”

(Patrick Verel and Janet Sassi contributed to this report. Various photographs were submitted by members of the Fordham community.)

[doptg id=”34″] ]]>

The Jesuit Career Center Consortium provides access to job postings and other resources for Fordham students interested in searching for jobs outside the metropolitan area.

This connection to the broader Jesuit community helped Chris Rittenhouse, GSB ’14, secure his job as an associate in account management at Tradition Energy in Stamford, Connecticut.

As he approached graduation, Rittenhouse decided to focus his job search in Boston or elsewhere in New England. Through the reciprocity program, Fordham’s Career Services office helped him connect with Boston College, another Jesuit institution.Within a month, Rittenhouse secured a job in a field about which he cares deeply. The Jesuit consortium, he said, gave him an edge.

“There was the additional benefit of being a part of a recruitment pool several states away in a city I am particularly keen to live in. That kind of flexibility and, more importantly, mobility, was awesome,” he said.

Kate Dunham, a sophomore in the Gabelli School of Business, is taking advantage of the reciprocity program as she works with the career services office of Loyola University Chicago to find a summer internship in Chicago.

Dunham said she has been deeply impressed by the program and the ease with which the Loyola career services office has answered her questions. She said the experience has helped her realize the value of the broader Jesuit community.

“I think it is such a perfect example of the Jesuit way of being men and women for others. It really doesn’t matter where you are in the country, you have people to help you out,” she said.

Cassie Sklarz and the Fordham Career Services team are constantly working to increase student awareness about the reciprocity program and all of the services Fordham offers. She said she’s pleased to keep supporting students through every step of their search—no matter where it might take them.

“For students applying elsewhere, this program gives a little bit of comfort and makes them feel a little more confident navigating the waters of their job search,” she said.

Students interested in accessing the resources of another Jesuit school should send their resume to Cassie Sklarz, associate director of Fordham Career Services. All requests for reciprocity must be handled through the student’s home school so that the partner school can verify the student’s enrollment or status as a recent graduate.

For more information about the Jesuit Career Center Consortium, contact Cassie Sklarz at 718-817-4358 or [email protected].

—Jennifer Spencer

]]>

Roche started the process by registering at annual Fordham football “Be the Match” registry last April. He completed a quick registration form and then submitted a swab of cheek cells using a cotton swab to determine tissue type and his results were stored in a database, awaiting a match.

“Everyone on the team was registering and we were encouraging others to register too,” said Roche. “I had no idea that I would be a match and get a phone call about helping to save someone’s life.”

The call came in August, at the beginning of the football season. Roche was asked to submit to further testing to determine if he would be compatible with the person in need, with the odds still being about one in ten for Roche being a perfect match.

In September, Roche got the call that would change his life. He was told that he was a match for someone in need of bone marrow. Even though it was in the middle of another successful football season, Roche didn’t hesitate when asked to donate, even if it meant he would have to miss football activities for a period of time.

“When I got the call and heard the other person say ‘thank you for your donation, you are a match’ a lot went through my head,” said Roche. “But it wasn’t very difficult to agree to do it, knowing that I could help someone in need.”

The original plan was to have Roche donate in October but he received a phone call that the recipient had taken ill and they would have to delay the procedure. A few weeks before thanksgiving, Roche was told that the donation was a go and on November 30, he started a four-day stretch in which he received shots in his arm and abdomen to prepare his marrow for donation. Then on December 3, he went to a blood center in Manhattan for the five-hour process.

“It was relatively painless,” said Roche. “They hook you up to a machine that removes your blood and separates out the marrow before returning the rest of the blood back into your other arm. The toughest part of the whole process was having to sit completely still the entire time.”

Roche was told that the recipient is now his “blood sister”, and that they both now have the same type of blood and genetic traits. “They told me that if I was allergic to anything that the recipient would now also be allergic to the same thing,” commented Roche, who also noted that he has no known allergies.

Roche isn’t the only one in his family who is a member of the Be the Match registry as his father is also on the list.

“My father’s been on the donor list for over 15 years and has never been called,” said Roche. “He’s jealous that I was only on the list for two months when they found a match. But in the end I think it’s cool that someone has the chance to live longer for what I did.”

Despite the odds, one thing is certain. Roche will be hard pressed to get anyone a better gift this Christmas than the one he gave to an anonymous woman.

]]>If you have been at Fordham for any time at all, you know that I am tireless—some would say relentless—in advocating for the University’s mission, in urging our students, and indeed all of you, to be men and women for others. I have said, many times, that I hope our graduates leave the campus bothered. Bothered by injustice. Bothered by poverty. Bothered by suffering.

This past year has had more than enough injustice, poverty, and suffering to go around—both in our own country and across the globe. We have seen pain and strife every day in Pakistan and Syria, in Ukraine and Russia, in Israel and Palestine, in West Africa, and Afghanistan, and Iraq; in Iguala and Isla Vista, in Ferguson and Staten Island. It has been an annus horribilis, and any sane person will be happy to see the end of it.

So this month let me urge something else upon you: compassion. Compassion, first and foremost for yourselves. Even those of us who have not been personally touched by tragedy this year have certainly seen enough of it play out in the news and on social media. So I wish for you the ability to be gentle with yourselves.

I hope, secondly, that you can have the same compassion for others. Many people struggle in their lives, and their struggles are not always apparent. Kind recognition of our shared humanity—meaning our shared imperfections—is a gift to both the giver and receiver.

Finally, I wish for you and your loved ones a Merry Christmas and a season of peace and light, and the many blessings that faith, family, and friends bring. I hope that the coming year will be your annus mirabilis: a year of love, fulfillment, prosperity, and joy.

I look forward to seeing you all in a brighter 2015.

Sincerely,

Joseph M. McShane, S.J.

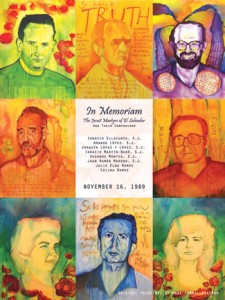

]]>Outside, more than three dozen Salvadoran soldiers had surrounded the University of Central America’s (UCA) Pastoral Center, where the six priests lived. Forcing their way into the quiet residence, the soldiers dragged the Jesuits outside and ordered them to lie facedown on the ground.

That morning, the world awakened to news of the most gruesome attack in El Salvador since the 1980 assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero. The six Jesuits had been executed in their front garden, while their cook Julia Elba Ramos and her 15-year-old daughter Celina—who had taken refuge at the residence after fleeing violence near their own home—had been shot to death in the bed they shared.

A Commitment to Justice

November marks 25 years since the killings, which have become emblematic of the civil war that ravaged El Salvador in the 1980s. An estimated 75,000 Salvadorans were killed in the decade-long war between a people’s movement and a U.S.-backed military government.

Father Ellacuría and his fellow Jesuits had responded to the violence by transforming UCA into a source of information about the political, economic, and social problems plaguing El Salvador. They documented the kidnappings, torture, and mass killings committed by military “death squads” and offered UCA as a venue for open debate.

“Father Ellacuría envisioned a new kind of university, one that focused all of its resources on what he called the ‘national reality,’” said Charles Currie, S.J., former president of Wheeling College and Xavier University. “He said the university had to be committed to teaching, doing research, and engaging in social outreach.”

Justice has always been at the heart of the Jesuit ethos, Father Currie said, but the dire situation in Latin America called for something radical. In 1975, Pedro Arrupe, S.J., Superior General of the Society of Jesus, called for the Jesuits to be “men for others” and implored them to embrace a “faith that does justice.”

“Our mission to proclaim the Gospel [demands]of us a commitment to promote justice and enter into solidarity with the voiceless and the powerless,” he wrote in the fourth decree of the 32nd General Congregation.

He also issued a caution: “If we work for justice, we will end up paying a price.”

Coming to UCA’s Aid

Following the murders, Father Currie traveled to El Salvador as a representative of Georgetown University. Many American Jesuits were coming to UCA’s aid, including the late Dean Brackley, S.J., who at the time was on the Fordham faculty. They found the capital, San Salvador, still embroiled in violence.

“We would go to meetings and would have to walk through gauntlets of soldiers, who would hit us with the butts of their rifles,” Father Currie said. “There was a lot of fear. You never knew what was going to happen when you opened the door—who would be out there and what they were going to do.”

At UCA, signs of the massacre were still evident.

“We went down there in early January, just over a month after the killings,” Father Currie said. “Blood was still on the ground. Everything had been left just as it was that night.”

And yet, there were also signs of what UCA had been a part of before it bore witness to the events of Nov. 16. The campus was alive with students walking to class or stretched out on the grass talking with classmates. Despite the trauma it suffered, UCA had refused to allow its spirit to be violated.

Justice and the Jesuit Campus

In the 25 years since the murders, Jesuit institutions have kept social justice at the core of their mission. A number of national initiatives evolved in direct response to El Salvador. Two of these are the Ignatian Family Teach-In for Justice, a yearly gathering to advocate for social justice issues, and the Ignatian Solidarity Network, which promotes leadership and advocacy among students and alumni.

Individual Jesuit institutions have responded on the local level withthe same ardor. Many Jesuit schools have centers dedicated to social justice, such as Fordham’s Dorothy Day Center for Service and Justice. Grounded in the philosophy of “men and women for others,” the center connects Fordham with the local community to promote service and solidarity.

“Our aim is to invite faculty and students into local partnerships that can place our hearts, research, and resources within the wider community,” said Jeannine Hill-Fletcher, Ph.D., faculty director of Fordham’s service-learning program. “We are inspired by Ignacio Ellacuría’s vision that the university is a social force and its heart must reside outside its gates.”

“I think it’s fair to say that no Jesuit campus today was the same after the killings in El Salvador,” Father Currie said. “Fordham has responded very generously to this vision, along with all of the Jesuit schools, by consciously committing to serving their local communities. I think that can trace back to what happened in El Salvador.”

To mark the 25th anniversary of the murders, presidents of Jesuit colleges and universities, advocates, U.S. politicians, and many others will travel to El Salvador. The delegation will meet with the nation’s leaders about urgent issues in the aftermath of the war, as well as visit sites related to the Jesuit martyrs.

The hope, Father Currie said, is to ensure for the Salvadoran people the justice that the Jesuits and their companions were denied.

“Peace without justice is not enough,” he said. “That doesn’t mean we should seek vengeance. But it is very important that we name the injustice so that we get to the root of the problem. Otherwise, peace becomes very fragile.

“The killing of the Jesuits represents a challenge to do just that,” he continued. “This 25th anniversary commemoration is the opportunity to recommit ourselves to a faith that does justice.”

The Westchester campus will celebrate a special liturgyThursday, Nov. 13.

Also on Thursday, Nov. 13 there will be a lecture at the Lincoln Center campus on the Jesuit martyrs and how they have influenced Jesuit institutions in the United States.

Twenty students will be attending the Ignatian Family Teach-In from Nov. 15 to Nov. 17, where Fordham theology professor Michael Lee will also speak.

At Rose Hill, there will be a prayer vigil on Sunday, Nov. 16 at 7:30 p.m., followed by an 8 p.m. Mass in the University Church, celebrated by Claudio Burgaleta, S.J. A meal of pupusas, a traditional Salvadoran dish, will be served after Mass.

]]>