“Universities are challenged in an urgent way by the questions that are now posed, questions that are after all existential, that are of the survival of the biosphere, of deepening inequality, of a return to the language of hate, war, and fear, and the very use of such science and technology yet again for warfare rather than in serving humanity,” he said.

The Sept. 30 lecture was part of the Ireland at Fordham Humanitarian Lecture Series, a partnership between the Permanent Mission of Ireland to the United Nations and Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs. (Watch the full lecture here.)

Higgins, a poet and former professor, said the Irish lost at least one million lives to starvation during the Great Potato Famine and saw more than 2.5 million emigrate. Therefore, the nation holds a collective memory that resonates with today’s crisis.

“We have known what it is to be hungry,” he said in his lecture, “Humanitarianism and the Public Intellectual in Times of Crisis.”

He noted that the Irish famine was editorialized in some newspapers as “an act of God.” The difference today, he said, is that the constant drumbeat of the news cycle desensitizes the listener.

“[Today,] we’ve become accustomed to narratives of how men and women throughout the world as refugees find themselves, through extended periods of time in unsuitable accommodation, confined to forced idleness, without even control over their daily diet,” he said.

Eugene Quinn, director of the Jesuit Refugee Service in Ireland, he noted, has said that children grow up “without the memory of their parents cooking a family meal.”

He lamented that millions of refugees spend years stranded in semipermanent camps around the world, while world leaders discuss the “internationalism and interdependency” of international trade.

“In fact [the conversation]nearly always begins with trade. This has devalued everything, really, in relation to intellectual life, and it has devalued diplomacy very seriously.”

He said that people’s loss of citizenship is so much more than a loss of a homeland. The rights of displaced humans become distinct from the rights of “the citizen.” Without citizenship, refugees lose their inalienable rights as a person, as well as their voice, he said, referencing Arendt.

“To be stripped of citizenship is to be stripped of words, to fall to a state of utter vulnerability with avenues of participation closed off, and thus new futures disallowed,” he said.

Given their past, he said that it falls to the Irish, at home and abroad, to be exemplary to those seeking shelter, especially since it is a crisis that will continue, fostered by climate change and exacerbated by precarious political situations.

“This is a deepening, if you like, of what I call the intersecting crisis of ecology, economy, and society,” he said.

But unlike the welcome that many European refugees received in the wake of World War II, today’s refugees have been shunned.

“The relatively small number of refugees reaching our borders [in the West] has brought forth the type of narrative about ‘the other’ that we in the humanitarian tradition had hoped was assigned to the chronicles of the past,” he said.

“Countries whose citizens have often benefited from international asylum and migratory flows are reneging on their commitments with the aim of discouraging or inhibiting refugees from seeking the international protection to which they are entitled.”

It is here, he said, that public intellectuals and universities must play a crucial role to alter a discourse “soured by hateful rhetoric.” However, he added that today’s charged atmosphere has not made it easier for the academy to exert influence, with some in the community seduced by corporate power, and others complacent with current economic models as the only way forward, he said.

He asked what is being taught in Economics 101 in North America, and questioned how much of it was game theory and how much was real political economy, to say nothing of the coursework’s moral content. He worried that an emphasis on funding beyond the state has had a disjointed effect on the career structure of young scholars.

“I believe public intellectuals have an ethical obligation as an educated elite to take a stand against the increasingly aggressive orthodoxies and discourse of the marketplace that have permeated all aspects of life, including within academia,” he said.

Edward Said said it best when he stated that an intellectual’s mission in life is to advance human freedom and knowledge, he said.

“This mission often means standing outside of society and its institutions and actively disturbing the status quo. Yet it also involves placing a strong emphasis on intellectual rigor and ideas, while ensuring that governing authorities and international intermediary organizations are well-resourced. To quote Immanuel Kant, ‘Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind.’”

President Michael D. Higgins will speak as part of Fordham’s Humanitarian Lecture Series

New York, New York, Sept. 17—Fordham University will host Michael D. Higgins, president of Ireland, on Monday, Sept. 30. He will speak at the Lincoln Center campus at 11 a.m.

President Higgins, who has campaigned for human rights, peace, democracy, equality, and justice throughout his years as a political leader, will deliver a talk on “Humanitarianism and the Public Intellectual in Times of Crisis” as part of the Ireland at Fordham Humanitarian Lecture Series, a partnership between the Permanent Mission of Ireland to the United Nations and Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs.

In his address, President Higgins is expected to focus on the impact of migration on Ireland and the United States, and the importance of adequate support in present circumstances for people forced to flee their homes as a result of poverty, conflict, or climate change.

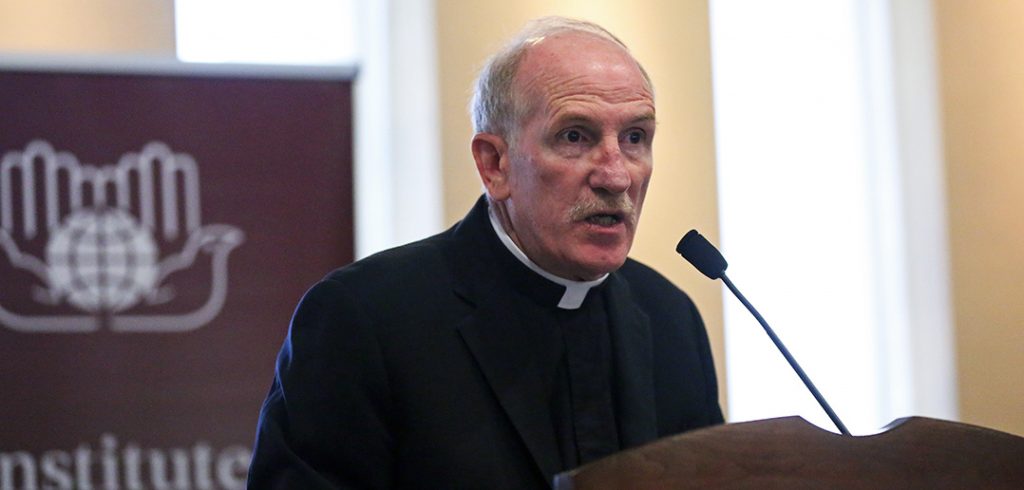

“Fordham is honored to host President Higgins, and to have him speak to the University community,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “He is an eloquent, compassionate, and thoughtful leader, and his commitment to serve the most vulnerable among us makes him an especially fitting choice to deliver this humanitarian lecture.”

Brendan Cahill, executive director of the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs, added, “At a time when world politics has become defined by how nations undermine international agreements, it is a great honor to welcome a leader who celebrates multilateralism, who speaks clearly about not only the Irish history of hunger, migration, and violence but its contribution to peace, to education, to an ethical and humanitarian approach to world issues.”

Michael D. Higgins has served as the president of Ireland since November 2011. A passionate political voice, poet and writer, academic and statesman, human rights advocate, promoter of inclusive citizenship, and champion of creativity within Irish society, President Higgins has previously served at almost every level of public life in Ireland, including as Ireland’s first minister for arts, culture and the Gaeltacht.

Born in Limerick City and raised in County Clare, he was a factory worker and a clerk before becoming the first in his family to access higher education. He studied at University College Galway, the University of Manchester, and Indiana University. As a writer and poet, he has contributed to many books covering diverse aspects of Irish politics, sociology, history, and culture.

President Higgins was the president of the Labour Party from 2003 until 2011, when he resigned following his election as president of Ireland.

The Ireland at Fordham Humanitarian Lecture Series, a multiyear partnership between the Permanent Mission of Ireland to the United Nations and Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs (IIHA), explores the challenges facing policymakers and humanitarians as they seek to ensure aid reaches those in need, that humanitarian principles are upheld, and that civilians are protected. Specific topics of discussion include humanitarian protection through international humanitarian law, humanitarian financing, climate and security. The inaugural lecture at the United Nations Headquarters in New York on April 29th by former President, H.E. Mary Robinson, Chair of the Elders. The series will run until June 2020 with events in New York, Dublin, and Geneva.

About Fordham University

Founded in 1841, Fordham is the Jesuit University of New York, offering exceptional education distinguished by the Jesuit tradition across nine schools. Fordham awards baccalaureate, graduate, and professional degrees to approximately 15,000 students from Fordham College at Rose Hill, Fordham College at Lincoln Center, the Gabelli School of Business (undergraduate and graduate), the School of Professional and Continuing Studies, the Graduate Schools of Arts and Sciences, Education, Religion and Religious Education, and Social Service, and the School of Law. The University has residential campuses in the Bronx and Manhattan, a campus in West Harrison, N.Y., the Louis Calder Center Biological Field Station in Armonk, N.Y., and the London Centre in the United Kingdom.

Contact:

Gina Vergel

[email protected]

(646) 579-9957

A significant multiyear partnership between the Government of Ireland and Fordham University, the lecture series will begin this month and run until June 2020 with events in New York, Dublin, and Geneva.

The series will consist of a number of distinguished lectures supported by more technical lectures and workshops that are open to all.

“Ireland and Fordham University have deep enduring connections,” said Ambassador Geraldine Byrne Nason, Ireland’s permanent representative to the United Nations. “Our historic ties are rooted in our strong commitments to respect for human dignity and spirit. … As we look toward the humanitarian challenges of the 21st century, such as climate change, gender equality, and ensuring respect for international humanitarian law, I can think of no better partner than Fordham. We believe that a better understanding of these complex issues is critical, as Ireland aspires to make a meaningful difference as a candidate for election to the U.N. Security Council, for 2021-22.”

Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, said the University is honored to take part in the project.

“Fordham is humbled and gratified by the trust that Ireland has placed in the University in creating this grant,” said Father McShane. “The lecture series brings fresh depth to the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs’ mission to educate men and women who are both committed to, and professionally trained in, helping the most vulnerable of our brothers and sisters around the globe.”

Lectures will explore the challenges facing policymakers and humanitarians as they seek to ensure that aid reaches those in need, that humanitarian principles are upheld, and that civilians are protected. Specific topics of discussion will include humanitarian protection through international humanitarian law, humanitarian financing, climate and security, and more.

Brendan Cahill, executive director of the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs, said the new series “complements the overall work of our institute and the leadership in this sector by the Irish government. These lectures and events, by leading U.N., government, and humanitarian leaders, will further inform and provide new insights in providing assistance to the most vulnerable.”

Speakers will include high-level political leaders who will communicate pivotal messages in response to key questions such as: What challenges and opportunities exist in humanitarian action in the 21st century? How do climate and gender drive food insecurity and humanitarian need? And, how can humanitarian action strengthen the role of local actors in humanitarian responses?

The inaugural lecture of the series will be delivered by H.E. Mary Robinson, chair of international NGO The Elders and the first woman elected president of Ireland (1990-1997). She is a former U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights and an advocate for climate justice, gender equality, women’s participation in peace-building, and human dignity. This lecture will take place on Monday, April 29 at 6 p.m. in the United Nations Sputnik Lounge. Learn more and register here.

]]>

The event included a prerecorded interview of former Senator George J. Mitchell, who chaired the peace negotiations as United States special envoy for Northern Ireland under President Bill Clinton. Irish Consul General Ciaran Madden spoke at the beginning of the program, and Fordham Law professors Martin Flaherty and Michael W. Martin presented on the past and future in Northern Ireland.

The landmark political development of April 10, 1998, helped resolve longstanding strife between the nationalists, who seek reunification with the Republic of Ireland and are mostly Catholic, and the unionists, who are generally Protestant and whose loyalties are with the United Kingdom. The agreement led to the region’s legislative devolution from the United Kingdom.

“This event was right there as one of the most important events in the history of the world, or what was accomplished by this incredible agreement signed twenty years ago this day,” said Robert J. Reilly LAW ’75, assistant dean of the Feerick Center for Social Justice, during his introductory remarks. Reilly also thanked the program’s sponsors: the Feerick Center, the Ireland Summer Program, the Leitner Center for International Law & Justice, the Irish Law Students Association, the Fordham Law Review, the Fordham International Law Journal, and the Conflict Resolution and ADR Program.

Consul General Madden stressed the importance of Northern Ireland’s ongoing commitment to remembrance and reconciliation. Desegregation, he said, remains a necessary act of all the region’s people.

“It’s the work of everyone in Northern Ireland and many outside it,” he said. “It’s not easy work. It’s slow work, but it’s so, so important.” Madden also stressed the viability of this work by quoting from the late Seamus Heaney’s poem “The Cure at Troy,” which encourages hope for justice and healing.

Illuminating the history that necessitated such healing, Flaherty described the last 400 years of Ireland’s long chronicle of suffering. After recounting some of the older history—including the migration of English and Scottish Presbyterian dissenters to Ulster in the 17th century, and the Irish Parliament’s voting itself out of existence in the late 18th century because it failed to take the rights of minorities into account—Flaherty discussed the violent conflicts between Protestants and Catholics in the last century. For a long time, violence reigned and mistrust thwarted resolution. Flaherty addressed the need to hold governments accountable for the violation of their laws.

“What we need today still is to keep this kind of scrutiny, this kind of pressure, on all parties to live up to the Good Friday Agreement because there still remains much, much work to be done before we can have true reconciliation, true peace, and true adherence to the human rights that everyone in that community on both sides deserves to enjoy,” said Flaherty.

Program attendees then watched a prerecorded interview of Senator Mitchell, the man who played a pivotal role in shepherding the agreement to approval. Mitchell received Fordham Law’s prestigious Stein Prize six months after the agreement’s approval in recognition of his work in Northern Ireland.

During the interview, adjunct professor John Rogan LAW ’14 asked Mitchell a series of questions about challenges and expectations both during the peace negotiations and after the agreement’s passing.

“It was less an expectation than hope,” said Mitchell, who recounted the stressful few weeks before the vote. The two sides’ mistrust of one another and their initial unwillingness to hear each other’s perspectives led to unproductive and even disastrous meetings. Nonetheless, the parties managed to reach a consensus after Mitchell set a deadline for ending the talks. “It was an enormous relief, a sense of great exaltation and exhaustion combined,” said Mitchell.

Mitchell observed how, although the agreement is a historical landmark, it does not itself guarantee peace; rather, it makes peace possible. “Peace is not a guarantee in any society, especially not in those with a history of violence,” said Mitchell. When that history of violence has included thousands of deaths and punishment beatings, which resulted in permanent maiming, the challenge is steep. Mitchell stressed how people need to be vigilant of violence’s ongoing threat, especially in the face of Brexit.

Nonetheless, the country has come a long way from where it had been. When Rogan asked Mitchell about how he feels looking back at his role in the peace process, Mitchell beamed with pride. “It was for me a labor of love,” he said. “Personally it changed my life.” He recounted how his involvement led him to connect with his Irish ancestry. “The experience filled in a void that I didn’t know even existed,” he said.

For the final portion of the program, Martin, who has led the summer program for Fordham Law students in Northern Ireland for the last 15 years, discussed the future of the region. Martin addressed current issues, including the restoration of a devolved government, the question of direct rule and the role of the Republic of Ireland, the implications of Brexit and a hard border, and the management of a still deeply polarized society.

“There are more walls today than there were in 1998,” said Martin, referring to the physical barriers that divide the Catholic and Protestant communities in Northern Ireland. “That just gives you an idea of a society that is divided, a society that is learning to trust but is not there yet.”

Despite the difficult issues, Martin noted how much progress has occurred since the agreement, including an improving economy and citizens’ increasing feelings of safety.

Martin also spoke over Skype with Niall Murphy, a human rights lawyer in Northern Ireland. Together, Martin and Murphy addressed the importance of remembering the past in order to forge a more peaceful future.

The event was the latest chapter in Fordham Law’s ties to Northern Ireland and the peace process. Former Dean John D. Feerick ’61 was part of President Clinton’s trip to Northern Ireland in 1995 that helped lay the groundwork for the peace talks. Dean Feerick also created a conflict resolution program for community leaders from the region and started Fordham Law’s Belfast/Dublin Summer Program. Additionally, alumnus John Connorton ’71, who was at the anniversary event, helped call attention to the conflict in the years leading up to the agreement by bringing political leaders from Northern Ireland to address U.S. audiences.

Northern Ireland’s peaceful future, according to Reilly at the program’s conclusion, can be sought by all of us. “Everyone, even from right here, from 3,000 miles away, can have a role in this peace process in the years to come,” he said.

—Lindsey Pelucacci

]]>The Tudors were a major European power that aimed to extend their political and social control into Ireland, which was at the time a decentralized and culturally alien region. The exhaustive Tudor conquests continued over  60 years, and still raise questions close to five centuries in the future.

60 years, and still raise questions close to five centuries in the future.

Frontiers, Stages and Identity in Early Modern Ireland and Beyond (Four Courts Press, 2016), is a new collection of original essays on historical Ireland assembled in honor of Steven G. Ellis, professor of History at the National University of Ireland. Maginn co-edited the collection along with Gerald Power, lecturer at Metropolitan University Prague. They asked Ellis’ former students, friends, and colleagues to submit essays based on, or inspired by, Ellis’ celebrated work as a scholar of early modern Irish and British history.

“The volume is geared primarily at academics and college-level students,” said Maginn. “It is our hope (the essays) will not only offer a fitting tribute to Professor Ellis, but will also singularly and collectively throw new light on areas of European history: from 14th-century Ireland to the Netherlands in the 16th century to Iceland in the 19th century.” Interested parties can find the Frontiers… collection here.

Maginn contributed his own essay to the volume: One state or two? Ireland and England under the Tudors. His piece explores whether the two Tudor kingdoms–England and Ireland–were regarded as being part of a united Tudor state, or whether they were treated as two separate states under Tudor rule. “These kinds of questions were a central feature of Professor Ellis’ research on the formation of the early modern British state,” he said.

Maginn has always had an interest in Tudor and Gaelic History, so the clash between Gaelic and English civilizations which occurred in Ireland was a neat fit for his interests, he said. Professor Ellis supervised Maginn’s doctoral thesis more than a decade ago at the National University of Ireland. In the years since, Ellis and Maginn have written two books together The Making of the British Isles: the state of Britain and Ireland, 1450-1660 (2007) and more recently, The Tudor Discovery of Ireland (2015).

– Kiran Singh

]]>The government of the UK’s nearest neighbor, Ireland, may prove to be one step ahead of its fellow EU member states in reckoning with the effects of Brexit. During an address given at Fordham Law School on Sept. 19, Ireland’s Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade Charles Flanagan told an audience of around 100 that his country had been preparing for a possible Brexit vote for a year.

“Expert reports were commissioned. All relevant government departments were asked to examine the possible impacts,” Flanagan said. “State agencies, business representatives, trades unions, and other stakeholders were consulted with and kept informed on the government’s approach.”

That approach stemmed from the country’s hope that the UK would stay with the EU. While the outcome of the vote disappointed Ireland, the government honors the process through which it was reached.

“Ireland was clear that we wished the UK to remain in the EU, as our analyses had shown that such an outcome best served our strategic interests,” Flanagan said. “However, by a narrow margin the result was otherwise, and the UK electorate voted to exit. The decision was a democratic one and we respect that.”

As the UK moves forward with its exit from the EU, the Irish government has reaffirmed its commitment as a faithful member of the EU and the Eurozone. Flanagan said that Ireland will continue to serve as a gateway to the EU for foreign investors. In speaking of Ireland’s contiguous border with Northern Ireland, Flanagan enumerated the particular challenges in the context of the UK region’s turbulent history with its southern neighbor.

“When the UK leaves the EU, Northern Ireland will be the only region in Britain which shares a land border with another EU member state,” Flanagan said. “One of our key concerns raised by Brexit is a return to a hard or fortified border dividing north and south.”

Flanagan went on to say that the reinstating of a hard border would negatively affect cross-border trade and economic activity. However, more serious would be the symbolic effect of resurrecting historical divisions.

Despite the challenges ahead, Flanagan sounded an optimistic note when he told the audience that Fordham values can inspire politicians and government officials during this uncertain time.

“As the European Union and Ireland prepares for a challenging period ahead, there is much to learn from the Fordham ethos,” Flanagan said. “Above all, there will be a need to apply what is emphasized in this University in terms of critical thinking and creative problem-solving.”

Left to right: John Feerick ’61, professor and former dean of Fordham Law School; Charles Flanagan, Ireland’s minister for foreign affairs and trade; Anne Anderson, ambassador of Ireland to the United States; Barbara Jones, counsel general of Ireland; Joseph McShane, S.J., president of Fordham University. Photo by James Higgins.

Left to right: John Feerick ’61, professor and former dean of Fordham Law School; Charles Flanagan, Ireland’s minister for foreign affairs and trade; Anne Anderson, ambassador of Ireland to the United States; Barbara Jones, counsel general of Ireland; Joseph McShane, S.J., president of Fordham University. Photo by James Higgins.

Áras Shorcha Ní Ghuairim

This summer, three Fordham students will trade in the Manhattan skyline for a panorama of Irish moors during two and a half weeks at Áras Shorcha Ní Ghuairim, one of the National University of Ireland Galway’s Irish language outreach centers.

Sarah Elizabeth Lahoud, FCRH ’12, Patrick Kelly, an FCLC rising senior, and Michael Dahlgren, an FCRH rising junior, are the recipients of 2012 Irish Language Scholarships from Fordham’s Institute of Irish Studies. The three will travel to Carna, a Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking region) in Connemara, in the west of Ireland.

“Carna, where the school is situated, is renowned for traditional arts, and is also an area of stunning natural beauty,” said Helen Maginn, administrative director of the Institute for Irish Studies.

Lahoud, who studied at University College Cork in Ireland during her junior year, said her participation in the Carna language program will be an opportunity for genuine cultural immersion, which isn’t always the case with study abroad experiences.

“I want to study the language in the Gaeltacht and expand my perspective,” said Lahoud, who graduated on May 19 with a degree in English. “Living in New York City, and my time at Fordham, have taught me that the university is only a fraction of a cultural experience, and that real cultural exchange happens when one is willing to immerse oneself in a culture.”

In addition to studying Irish at Áras Shorcha Ní Ghuairim, the students will take an Irish culture course to learn about traditional signing and dancing, folklore, and local traditions of the Gaeltacht.

For Lahoud, that will include honing skills she picked up in Cork City.

“The class I took on ancient Irish vision texts [at University College Cork]inspired me to write my senior thesis, and I even started playing the tin whistle and still play traditional Irish music here in New York,” she said. “I am also extending my Irish trek this summer to attend two summer schools to play Irish music.”

Established in 2008, the scholarship is funded by a grant that the Institute receives annually from the Irish Government’s Department of Arts, Heritage, and the Gaeltacht. To date, nine Fordham students have been awarded the scholarship.

“They will no doubt be outstanding ambassadors for Fordham and for the Institute of Irish Studies,” Christopher Maginn, Ph.D., director of the Institute for Irish Studies, said about this year’s cohort.

Go dté sibh slán!

— Joanna Klimaski

Of course, when it comes to learning Irish, Midtown Manhattan has nothing on the Emerald Isle, which is why we’re excited that the institute has awarded Sarah Rose Sullivan and Colleen Taylor, both sophomores at Fordham College Rose Hill, Irish language scholarships.

The scholarships, say institute director Christopher Maginn, PhD, F.R.H.S., Assistant Professor of History, will enable Sullivan and Taylor to travel to the West of Ireland in July to study the Irish language at the National University of Ireland, Galway.

We wish them both the best of luck of the Irish.

—Patrick Verel