At the Climate Action Summit held April 8 at Rose Hill, several elected officials were on hand to celebrate Fordham’s new role as an EPA grantmaker. U.S. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer told the crowd, “We couldn’t have thought of a better place than Fordham” to dispense the federal funding, which will go to grassroots groups focused on climate justice.

Answering a call from Pope Francis, Fordham is indeed a place committed to taking “concrete actions in the care of our common home.”

Here are some updates from the first quarter of 2024, from student sustainability interns to “cool” foods to fun community events that make an impact.

Facilities

In January, 11 more undergraduate students joined Fordham’s Office of Facilities Management as sustainability interns to help the University in its efforts to reduce its carbon emissions. They’re working on projects connected to AI-enabled energy systems, non-tree-based substitutes for paper, and composting. The office is still looking for three more students to join; email Vincent Burke at [email protected] for more information.

Dining

Stroll into a dining facility at the Rose Hill or Lincoln Center campus, and you’ll find “Cool Food” dishes such as crispy chicken summer salad, California taco salad, and spicy shrimp and penne.

The dishes, which are marked by a distinctive green icon at the serving station, have a higher percentage of vegetables, legumes, and grains, which generally have a lower carbon footprint than those with beef, lamb, and dairy. According to the World Resources Institute—which Fordham partnered with on the Cool Food project—more than one-quarter of the world’s greenhouse emissions come from food production.

In March, the University went one step further by signing onto the New York City Mayor’s Office Plant-Powered Carbon Challenge. The pledge commits Fordham and Aramark to reduce our food-supply carbon emissions by a minimum of 25% by the year 2030.

Academics

This semester, a new one-credit, university-wide experiential learning seminar titled Common Home: Introduction to Sustainability and Environmental Justice was taught by faculty and staff from the Gabelli School, the Center for Community Engaged Learning, the Department of Facilities, the Department of Biology, and the Department of Theology.

Other sustainability-focused courses this semester include the City and Climate Change, the Physics of Climate Change, and You Are What You Eat: the Anthropology of Food (Arts and Sciences); Sustainable Reporting and Sustainable Fashion (Gabelli School of Business); and Energy Law and Climate Change Law and Policy (Law).

Students Take the Lead

At Fordham Law School, the student-run Environmental Law Review hosted a March 14 symposium that considered the impact of artificial intelligence on environmental law. Panels focused on how regulators and litigators can use AI and the challenge of addressing AI-generated climate misinformation.

In January, Fordham Law student Rachel Arone wrote The EPA Rejected Stricter Regulations for Factory Farm Water Pollution: What This Means, Where Things Stand, and What You Can Do for the Environmental Law Review. And the Law School’s student-faculty-staff collective Climate Law Equity Sustainability Initiative held a series of lunchtime discussions about climate change, law, and policy.

Student groups LC Environmental Club and Fashion for Philanthropy teamed up on March 8 to create reusable tote bags on International Women’s Day. The bags were donated to Womankind, which works with survivors of domestic/sexual violence and trafficking.

The United Student Government Sustainability Committee continues to run the Fordham Flea, a student-run thrift shop that connects students interested in selling old clothes with those looking to buy sustainably. The next flea will take place on April 26 from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. outside of the McShane Center.

Community Engagement

The Center for Community Engaged Learning (CCEL) held an Urban Agriculture and Food Security Roundtable on Feb. 2. The gathering brought together community organizations and leaders from the Bronx to discuss urban agriculture and food security. Attended by Bronx Congressman Ritchie Torres, the meeting was also an opportunity for groups to learn about resources available from the USDA and the New York City Mayor’s Office on Urban Agriculture.

CCEL Director of Campus and Community Engagement Surey Miranda-Alarcon served as a panelist at a March 9 climate justice workshop at SOMOS 2024 in Albany, along with Mirtha Colon, GSS ’98, and Murad Awawdeh, PCS ’19.

Faculty News

David Gibson, director of the Center on Religion and Culture, and Julie Gafney, Ph.D., director of the Center for Community Engaged Learning, attended “Laudato Si’: Protecting Our Common Home, Building Our Common Church” conference at the University of San Diego on Feb. 22 and 23.

Marc Conte, Ph.D., professor of economics, and Steve Holler, Ph.D., associate professor of physics, presented their research around air quality, STEM education, and education outcomes on March 11 at the first night of Bronx Appreciation Week, which the Fordham Diversity Action Coalition organized.

Alumni

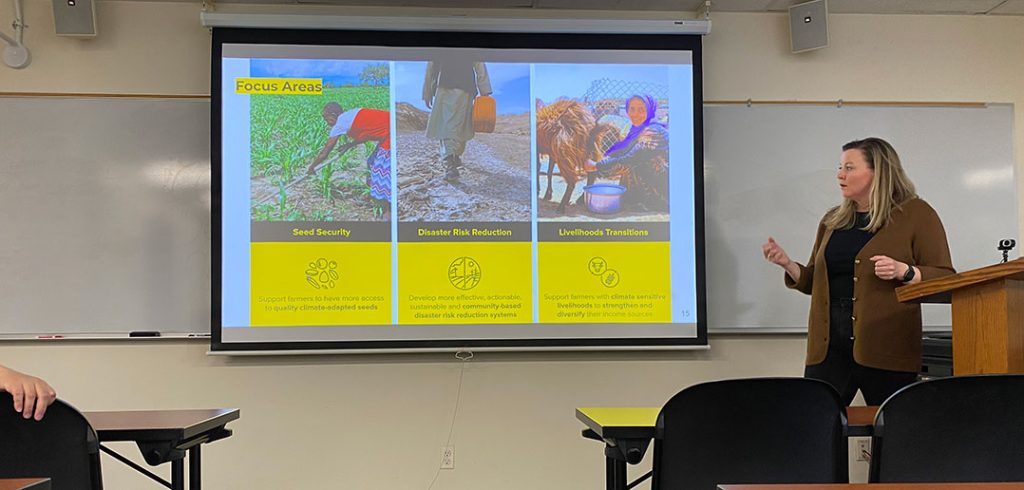

On March 14, Tara Clerkin, GSAS ’13, director of climate research and innovation at the International Rescue Committee, delivered a lecture at the Rose Hill campus titled “The Epicenter of Crisis: Climate and Conflict Driving Humanitarian Need and Displacement.”

In Case You Missed It

Here are some sustainability-related stories that you may have missed: In January, economics professor Marc Conte published the findings of a study that examined whether people living in areas with more air pollution suffer more from the coronavirus. The Gabelli School of Business partnered with Net Impact, a nonprofit organization for students and professionals interested in using business skills in support of social and environmental causes. A group of the Gabelli School Ignite Scholars traveled to the Carolina Textile District in Morgantown, North Carolina, to learn the benefits of sustainable and ethical manufacturing.

Upcoming Events

April 12 and 19

Poe Park Clean-up

In celebration of Earth Day on April 22, the Center for Community Engaged Learning is organizing visits to the park, where volunteers can help pull weeds and spread mulch. 10 a.m. – 2 p.m., 2640 Grand Concourse, the Bronx. Sign up here.

April 13

Bird Watching in Central Park

Law professor Howard Erichson will lead students on a birdwatching tour of Central Park, where they hope to spot and identify a few of the hundreds of species that pass through Fordham’s backyard on their annual migration routes. Meet at the Law School lobby at 9:30 a.m. Contact [email protected] to reserve a spot.

April 13

Ignatian Day of Service

Students and alumni will meet at the Lincoln Center campus and walk over to nearby Harborview Terrace, where they will build a community garden with residents. Lunch and a conversation about Ignatian leadership will follow. 10 a.m. – 2 p.m.

Click here to RSVP.

April 15

ASHRAE NY Climate Crisis Meeting

The theme of this meeting of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers is “Challenge Accepted: Tackling the Climate Crisis.” All are welcome.

7 a.m.- 1 p.m., Lincoln Center Campus. Contact Nelida LaBate at [email protected] for more information or register here using code FordhamStudent2024.

We’d Love to Hear From You!

Do you have a sustainability-related event, development, or news item you’d like to share? Contact Patrick Verel at [email protected].

]]>

In an address at the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization last year, Pope Francis issued a challenge to find new ways to “confront hunger and structural poverty in a more effective and promising way.”

In an address at the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization last year, Pope Francis issued a challenge to find new ways to “confront hunger and structural poverty in a more effective and promising way.”

On Sept. 28, Fordham addressed the problem, with “Reduce Hunger: Pope Francis’ Call for New Approaches,” a day-long conference presented by the Centesimus Annus Pro Pontifice USA Foundation and the University’s Graduate Program in International Political and Economic Development.

Archbishop Bernardito Auza, apostolic nuncio and permanent observer of the Holy See to the United Nations, opened the day’s events with a morning talk, and after a day of presentations, panels and workshops, Archbishop Paul Gallagher, secretary for relations with states at the Holy See, closed it out with a dinner address at Fordham Law School.

Photo by Patrick Verel

Economist Christopher Barrett, Ph.D., mapped out the challenges facing humanity in a morning presentation titled “Meeting the Global Food Security Challenges.”

Barrett, the Stephen B. and Janice G. Ashley Professor of Applied Economics and international professor of agriculture at Cornell University, was quick to note that the progress that’s been made on the issue of food insecurity over the last 50 years has been “nothing short of astounding.”

Remarkable Progress

As recently as the late 1940s, he noted, his grandmother found herself in dire straits in the Netherlands in the immediate aftermath of World War II, something that’s inconceivable today, he said. Likewise, the number of children suffering from stunted growth has shrunk dramatically in recent years, thanks in part to the “green revolution,” which Barrett described as innovations during the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s in agricultural production technologies, improved seed varieties, improved varieties of inorganic fertilizer, and better water management.

“There are remarkable accomplishments in improving the productivity of the earth in producing the food to sustain people. Today we have more than six billion people getting enough dietary energy intake, which is a tripling over the course of my lifetime,” he said.

“But agriculture is a treadmill. There’s always a pressure carrying you backwards, and if you don’t run, you’ll get slammed into something behind you that you can’t see.”

Governments and industry grew complacent in the late 1980s and ’90s, he said, and slowed its investment in global agricultural research and development. The result is that global food prices hit their all-time inflation-adjusted low point from 2000 to 2002; today the cost of food is 50 percent higher than it was just 15 or so years ago.

Changing Needs

Barrett said part of the problem is that research has returned to boost the productivity of wheat, corn and rice, but as human diets have improved, what’s needed more now are micronutrients such as vitamins and minerals. Today, for instance, the leading cause of blindness in children is simple beta keratin deficiency. When your grandmother told you to eat your carrots, she was serious, he said.

“But we need access to carrots. Fresh fruits and vegetables, animal-sourced fruits, the primary sources of the vitamins and minerals essential to an active, healthy life, don’t come from cereals, although there’s some remarkable improvements taking place through biofortification,” he said.

“Zinc deficiency, iron deficiency, these things are serious limitations of human performance, and this where we need to be focusing far more of our energy today.

“The old approach of grow the pile of rice, was important in the 1960s and ’70s. We’ve largely figured out how to do that, and we can’t take our foot off the pedal. But we need to be increasingly turning our attention to these other dimensions that we didn’t spend enough time on before.”

Poverty Traps

Another change from years past is that human suffering has also become much more geographically concentrated. The number of people who could be classified as the ultra poor, which is someone who subsists on 95 cents a day, has declined dramatically from roughly half a billion a generation ago, with about a 120 million of those people in Sub-Saharan Africa. Today, there are 150 million ultra poor, but the percentage in Africa has grown. Today eight out of ten of the ultra poor live in Sub-Saharan Africa, and in South Sudan, Yemen, and a small number of other nations.

Encouraging Developments

Many encouraging trends are emerging thanks to innovations from both the private sector and governments, Barrett said. Genetic engineering, for instance, holds great promise, and he urged attendees not to dismiss it.

“How many of you want your grandchildren to eat banana or papaya? You have nearly no hope of that happening without genetic engineering. The papaya industry has been saved through genetic engineering against ring spot virus,” he said.

“It’s not that all of it is good, and you have to have careful regulatory controls over things. But why should we tie our hands behind our back when we have a big fight ahead of ourselves? Some of these technologies are going to be essential to us.”

Barrett was also optimistic about innovative projects underway that attempt to recover phosphorus, which can be used for fertilizer, from the bones of dead animals. Food loss and waste is unfortunately inevitable, so recapturing what is a necessary waste. Above all, he said, this is team sport.

“This is not something that anybody is going to solve individually. There are too many moving parts,” he said.

A Message from Pope Francis

The dinner, which took place on the 7th floor of the Law School, was attended by Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, as well as Archbishop Auza,; Daniel Gustafson, Ph.D., deputy director general, U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization; Bill O’Keefe, vice president of Catholic Relief Services; Eutimio Tiliacos, Ph.D., secretary general, Centesimus Anno Pro Pontifice, Vatican City; Fred Frakharzadeh, M.D, president, Centesimus Anno Pro Pontifice, USA, and several university professors who specialize in agriculture and food security.

At the dinner, Archbishop Gallagher was presented with a copy of Fordham University’s Pope Francis Global Poverty Index, a multidimensional measure of international poverty inspired by the pope’s address to the United Nations General Assembly in 2015.

In a statement issued Saturday by the Vatican, Pope Francis thanked Fordham for organizing the conference, noting that as with many of the social and humanitarian challenges confronting the international community, his approach to reducing hunger “is not based on mere sentiment or a vague empathy.”

“Rather, it is a call for justice, not a plea or an emergency appeal. There is a need for broad and sincere dialogue at all levels, so that the best solutions can emerge and a new relationship among the various actors on the international scene can mature, characterized by mutual responsibility, solidarity, and communion,” he said.

]]>“That would be the greatest transfer of human capital that we’ve seen in recent times,” he said of the move that would send 800,000 law-abiding, economically productive U.S. residents to Mexico. “It would transform Mexico in a very positive way, but of course this isn’t what the DACA recipients want. They’ve spent most of their lives in the United States, and even though they were born in Mexico or other countries, they believe this is the country they call home.”

In a wide-ranging Q&A at the Rose Hill campus on Oct. 3, Gomez-Pickering lamented the fact that in the United States, the word “immigrant” has become synonymous with “criminal.” He detailed his government’s efforts to aid DACA recipients and its response to last month’s earthquake in Mexico City. He also remarked on the ties that bind Mexico to the United States, New York City, and Fordham.

An Unbreakable Connection

The United States was the first country to recognize Mexico as an independent state in 1821, he said. In 1848, when the Mexican-American war ended, he noted that 110,000 families in Texas woke to find themselves living in another country. Even today, the economic and cultural bonds between San Diego and Tijuana are strong.

“It might seem that the U.S. and Mexico are going through a rough time, but that’s not necessarily the case. On an everyday basis, the relationship is still there. We’re much more than neighbors, because if you don’t like your neighbor, you can just move to another building.”

“We’ve got to stick together as we have been, in a positive manner.”

Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, said that the University’s connection with Mexico is “longstanding, deep, and enriching.” He noted that one of the University’s most valuable artworks, the eight-foot-high painting Adoration of the Magi, which is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art until the end of the month, was created by the Mexican painter Cristóbal de Villalpando.

“In the 19th century, shortly after our founding, we had a very substantial number of students from the Caribbean, including the coast of Mexico, as part of our community. So our connection with Mexico is rich,” he said.

Welcoming Refugees

Monica Olveira, a Fordham College at Rose Hill senior majoring in International Political and Economic Development (IPED) who works with UNICEF, used the opportunity to ask Gomez-Pickering what the country is doing to help children who are migrating there from countries like Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador.

“Mexico has always been a very welcoming country to refugees. If you look back at the later part of the 20th century when all the military coups happened in South America, Mexico was the number one destination for many political refugees,” Gomez-Pickering said.

He said that the Mexican government holds meetings at least once a with representatives of countries in the “Northern Triangle.” The goal is to aid migrants, particularly those who travel by themselves.

“That’s something that continues, especially for our brothers and sisters from Latin America.”

Gomez-Pickering’s visit was sponsored by Fordham’s Latin American and Latino Studies Institute (LALSI).

]]>Frazier’s visit was cut short, as was her work with Timap for Justice, the country’s largest paralegal network. A former Peace Corps volunteer in Rwanda, Frazier had been helping develop organizational assessment tools and training materials, and observing paralegal activities in Timap’s various offices around the country.

For a year, Frazier worked remotely for Timap as best as she could from the United States. She graduated a year later with a master’s degree in economics and international political and economic development (IPED), and worked as an adjunct professor with Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs.

In October of 2016, she came back on a yearlong Fulbright scholarship to continue her work with Timap.

“When I was here last time [during the Ebola outbreak], it struck me how much of the epidemic’s consequences weren’t just going to be health-related. There were going to be many more systematic problems related to socioeconomic recovery and access to civil justice issues,” she said.

Her fellowship involves exploring new ways that the legal system can handle civil justice cases, particularly those of a commercial nature. When the Ebola epidemic was in full swing, a great deal of economic activity arose from responding to it. Now that it’s ended, Frazier said the time is right to explore avenues for these cases to be resolved.

“Do we look for cases that involve debt, breach of contract, or land tenure? Or is it about the total amount of money involved in the claim? What does it look like to handle commercial cases in a way that could alleviate pressure from the legal system through alternative routes? That’s what we’re in the process of looking at,” she said.

Frazier splits her time between Timap’s offices in Freetown, where she writes proposals and reports, and in towns three to six hours away from the capital, where she visits local Timap paralegals and judicial officials to measure the demand for commercial alternative resolution services. Although she is learning Krio, the official language of the country, she still relies on an interpreter who can help her reach speakers of Mende, Temne, or any of the other 17 tongues spoken in the provinces.

Sierra Leone has a formal legal system based on the British Colonial common law that features courts, correctional centers, and police stations. It’s a dualist system though, so local chiefdoms also have a say in some matters, she said.

“As you can imagine, navigating that can get complicated for an ordinary Sierra Leone resident,” said Frazier.

“On top of that, the formal legal system is much more limited in terms physical facilities. The customary legal system has a far wider reach, but it has a slightly different scope. A lot of times, legal aid and access to justice services like Timap are a bridge between those two.”

The work is challenging, and Frazier admits she occasionally feels overwhelmed. But she’s inspired by the camaraderie and resolve that was borne of the efforts of those who worked together to stop the epidemic, as well as her colleagues at Timap.

“It’s very much a transition stage here right now, which I always find to be a fascinating time in a country,” she said. “But it’s very difficult for a lot of people.”