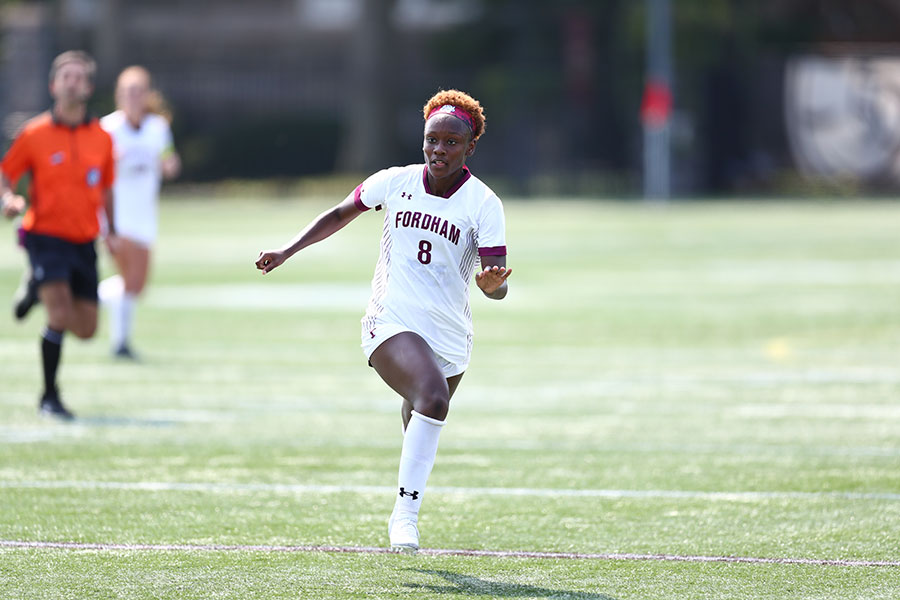

Etienne’s journey to the World Cup has been fueled by her experiences at Fordham, where she played three seasons for the Rams, and by five years competing for the Haitian national team. Her paternal grandfather immigrated to the U.S. from Haiti, and she grew up in Paterson, New Jersey. She said representing her ancestral country—and particularly being part of something positive for a nation in turmoil—is the highlight of her young career.

“It’s definitely an honor and a privilege,” she said from her hotel in Perth, Australia, just ahead of the World Cup. “We know what happiness the team brings to the country. Every time we step out on the field, it’s kind of our responsibility and we don’t take it lightly.”

Here are six things to know about Danielle Etienne.

1. She helped put the Haitian national team on the sport’s biggest stage.

While Haiti is making its first appearance in a Women’s World Cup, this is a second of sorts for Etienne, who, along with several current teammates, had a tiny taste of the world stage when she participated in the U-20 World Cup in 2018.

“I was 17 years old, going to the U-20 World Cup, and I felt like I was even younger,” she said. “I definitely feel a little bit more mature now, and have more composure, more experience. And I think it also feels different because it’s the FIFA Women’s World Cup. This is what I watched as a little girl. I’d grown up watching my idols, like Marta, at a World Cup, and now I’m playing in the same World Cup as her. That’s insane!”

2. Soccer is in her DNA, and her father and brother help keep her focused.

Etienne lives by the motto “Faith, Family, and Football.” Her father, Derrick Etienne Sr., played professionally in the U.S., and her brother, Derrick Jr., is a midfielder with Major League Soccer club Atlanta United. Both played for the Haitian national team. So, when they give advice, she listens.

“My father always told me and my brother that we have to work for everything that we want, and we can’t expect anything to be given to us,” Etienne said. The other voice in her head is her brother’s, guiding her when she gets sidetracked by those who doubt her.

“I was giving other people so much power and letting their words affect me. My brother told me, ‘Don’t worry about proving people wrong, worry about proving yourself right.’ I know I have the talent, I know I have the potential. I just have to put in the work.”

3. She had a special feeling about Fordham when she visited Rose Hill.

Etienne had three criteria for selecting a college: great academics, a strong soccer program, and proximity to her family in New Jersey. Fordham checked all the boxes.

“Once I got on campus, I felt it,” she said. “I felt like it was the right place and environment. And then I actually got to talk to girls on the team, and you could tell they were just so genuine. They were very forthcoming in terms of information and what their experience was like. And talking to the coaching staff as well, and understanding what they wanted to do within the program, to build the team. So, the combination of those things all kind of just made it into a very great package for me.”

Etienne was named to the Atlantic 10 Conference All-Rookie Team in 2019, and she earned a spot on the A-10 Commissioner’s Honor Roll in each of the three seasons she competed for the Rams.

4. During the pandemic, and Fordham’s “season without sports,” Etienne helped advance the University’s anti-racism action plan.

Etienne said that in 2020, amid social unrest and calls for racial justice after the killing of George Floyd, she was fortunate to have a supportive team environment where she could share the concerns she had—about her brother or father being pulled over by the police, the stressors of attending a predominantly white institution, and everyday microaggressions. What started as a conversation with her soccer teammates led to a diversity, equity, and inclusion group that branched out into the athletics department at Fordham. Etienne led the subcommittee on education and worked to bring in speakers of color who discussed their experiences.

“It’s one of the things I’m very proud of, leaving that at Fordham,” said Etienne, who received an Ignatian Social Justice/DEI Award from the Fordham athletics department in 2021. “Knowing that I didn’t just say, ‘I’m a student-athlete.’ But there are some things that are going on in the world that we have to acknowledge. And then we have to see what we can do to be better. Because if we’re not part of the solution, then we’re part of the problem.”

5. She’s inspired by the growth of the women’s game both in the U.S. and globally.

Etienne points to the historic U.S. women’s national team’s win for equal pay, the talent of the players in the National Women’s Soccer League as well as the expansion of the league, and the support for players, like her, who have children and return to the game.

“I’m proud that this is the era that I’m in now, and that I have even more opportunities because of all the people who came before me,” she said. “Knowing what it was like 10, 15 years ago, and seeing how much progress has been made, I’m proud of how far we’ve come.”

6. Her Fordham psychology degree and volunteer work are prep for her post-soccer career.

If she wasn’t playing soccer, Etienne said she would be working to make a difference in her community and counseling those in need. With the Etienne Family Foundation, started by her brother, she has helped support youth in her hometown of Paterson, New Jersey, conducting fitness and soccer clinics and raising money for equipment and places to play. They also organize coat drives and fundraisers to bring supplies to the many in need in Haiti.

“It is important you remember that there are so many people who are less fortunate than you, and who deserve a chance as well,” she said. “And the next Messi or the next Marta can be sitting in Haiti with no cleats right now.”

—Tracey Savell Reavis, FCLC ’01, is a veteran journalist with more than 20 years of writing, editing, and teaching experience, and author of a book on the career of footballer David Beckham (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014). She publishes The Club, a newsletter covering the U.S. national teams and world football. Traveling to New Zealand to cover her first World Cup is a dream come true.

]]>In an online conversation on June 16, Westenley (Wes) Alcenat, Ph.D., an assistant professor of history, urban, American, and African American studies at Fordham, and Rafael Zapata, Fordham’s chief diversity officer, discussed how the two events are tied to each other.

“You have this classic example of hundreds of thousands of people who were free in Texas but would remain unfree for another two years because the news was suppressed,” Alcenat said.

Just as the news of the Emancipation Proclamation took years to reach enslaved people in Texas, the news of the Haitian revolution—and the French Revolution—took years to reach Black men and women who might have been emboldened by such victories.

“If you go back to 1791, not only were words of the French Revolution being suppressed among the enslaved population in Saint-Domingue (as it was known back then) but news of the Haitian revolution, which lasted over a decade, was suppressed among the free Black and enslaved population here in the United States,” he said.

When the Haitian people finally won their independence from France in 1804, it also had unexpected consequences for the United States, he said. In a sense, it was both a gift and a curse for Black and indigenous people.

“It’s a gift in the sense that, nowhere else had this ever taken place before in human history—enslaved people rebelling and fomenting a revolution that established a state,” he said.

“At the same time, with the loss of Saint-Domingue as such a productive colony, France all of a sudden found itself without the funds to continue its many continental wars, so it turned over the Louisiana territory to the United States, which doubled the size. So, the domestic slave economy in the U.S. expanded very fast.”

Victory also brought serious hardships to the new Haitian nation, as the French would demand punitive reparations for its “loss of assets.” A recent New York Times investigative series, The Ransom, showed how two centuries of debt and dependency would follow.

While Haiti is still to this day struggling to thrive as a nation, Alcenat, a Haitian native, said that the principles guiding its founding can be found in the spirit of today’s Black Lives Matter movement.

When the country was formed, “Haitian constitutionalism,” as he dubbed it, granted citizenship to anyone who was indigenous or of African descent. Most of the indigenous inhabitants had been massacred by Christopher Columbus, but the move symbolically restored dignity to those who claimed the land first. Even the name of the new country, Haiti, which means “island of mountains,” was the name the indigenous inhabitants had chosen for the island.

“It’s not reparations in the conventional wisdom, but as a returning of dignity to that to whom it belonged and humanizing the indigenous folks whose land this was in the first place, and in the process, claiming for themselves a new form of indigenity,” he said.

What really connects the Haitian constitutionalism to Black Lives Matter was the principle that said that for someone to become a Haitian, they first had to declare themselves Black. Under the new post-revolution laws, white males were explicitly banned from owning land and property.

“This is the precedent to the Black Lives Matter, because what it’s saying is, the degraded, the dehumanized, the oppressed, those who are at the very bottom of society, we are going to reverse the order. They really do know what freedom is because they also know what non-freedom looks like,” he said.

“There are historians who very much want to argue that this was reverse racism, and excuse my French, but that is pure B.S. It had little to do with whiteness because in fact, white men could become Haitian. All they would have to do is say, ‘I declare myself Black,’” Alcenat said.

It wasn’t an abstract concept either, as he noted that during the war, 400 to 500 Polish soldiers who had been sent by Napoleon to reclaim the island and reimpose slavery defected from the French army and stayed on the island permanently. Their descendants can be found there to this day.

“In order to incorporate them into this new revolutionary society, the Haitians had to find a way to assert the principle of Black freedom, but not have that principle restricted by race,” he said.

“So Black freedom is, in a sense, the most capacious, most expansive form of freedom that was allowed.”

Zapata noted that although this was the third time the University had honored Juneteenth, this was the first event that connected it to research on Black liberation.

“The Haitian revolution was always an important piece to the notions of freedom,” he said.

“I can think of no better way to honor Juneteenth than to honor our outstanding faculty whose research is so close to this work”

The conversation was sponsored by the Office of the Chief Diversity Officer, the Office of Multicultural Affairs, and the Office of the Provost.

]]>

The “fair trade fair” will take place at the Lincoln Center campus on April 22, 23, and 24, and will feature crafts made in Haitian, Kenyan, and Guatemalan communities.

“We’re trying to connect artists in these developing communities with consumers,” said Pinar Zubaroglu, a doctoral candidate at the Graduate School of Social Service.

Erick Rengifo Minaya, Ph.D., an associate professor of economics and founder of Spes Nova, enlisted Zubaroglu, who traveled frequently to Haiti as part of her dissertation research, to help make contacts with artists there.

“Working in Haiti I began to realize that there are so many challenges, but the people are so resilient,” she said.

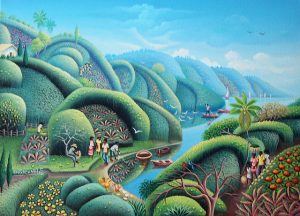

Andrew Meade, Ph.D., co-founder of the Vassar Haiti Project, said the peoples’ resiliency is reflected in their artistic creations.

“It’s accessible art. It reaches out and grabs you with rich colors and a subject matter rich with joy,” he said.

The Vassar group will be bringing 200 paintings and hundreds of handmade crafts to the event, he said. The event will feature a panel discussion titled “Communities at Risk: Social Justice in the Developing World” at 4 p.m. on Saturday, April 22. Panelists include, Vinay Swami, Ph.D., professor and chair of French and Francophone Studies at Vassar, Patrick Struebi, founder of Fairtrasa, and Sean Murray, associate professor of Core Studies at St. John’s.

“A lot of organizations try to do this kind of work alone, but all the groups participating really believe in fair trade—not just the concept but in the application of it,” said Meade. “Through their arts and efforts, we are empowering all three communities.”

The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and the Gabelli Business School will also participate in the three-day event. Proceeds will go to support Spes Nova, the Vassar Haiti Project, and student-driven fair trade groups at St. John’s.

See a schedule of events.

]]>“When it comes to the materialistic part of the holiday season, I can’t handle it,” she said. “I’ve changed.”

Lightburn recently flew into New York from Haiti, where she is helping Dominicans of Haitian ancestry who have been pouring over the border into Haiti from the Dominican Republic. In 2013 the Dominican government ordered that the group must prove Dominican lineage with ancestral birth certificates dating from before 1929, or be expelled. An estimated 200,000 people may become stateless.

Lightburn said that the mere act of traveling home for the holidays has taken on a new meaning.

“I see how restricted other people are in traveling,” she said. “The people there are dealing with the statelessness and no visas.”On returning to New York, Lightburn sat on a panel held at Fordham to discuss the crisis. Before the event, she checked in with colleagues from the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs (IIHA), where she is pursuing her master’s degree, and then met with her mother, Anita Lightburn, PhD, a professor in the Graduate School of Social Service and director of the Beck Institute on Religion and Poverty.

The two discussed their shared interest in helping those in need—Professor Lightburn through social work and Kara Lightburn through humanitarian aid—though Professor Lightburn continually deflected attention from her work to that of her daughter.

“Being on the ground and doing the work that Kara does is a whole different thing than me organizing people to understand social justice issues and respond,” she said.

While she has seen her share of human frailty over the years, the professor recognized that her daughter’s experience in Haiti is distinct. Kara began going to Haiti to help out after the 2010 earthquake. That year, she founded Social Tap, a New York-based nonprofit providing services through Haitian partnerships.

“She’s like her father in that she really goes out on the edge, has a vision for what could be, and then she goes ahead and does it,” Lightburn said. “She’s never taken a salary, never funded herself. Everything she gets she gives away.”

But Kara said she learned how to organize disparate parties toward a common goal by observing her mother and her colleagues.

“Because of my mother, I was always surrounded by amazing, powerful women who were intellectually challenging,” she said. “I learned how to tap into the university systems because I grew up in them and learned how to work with multiple institutions.”

Her first time on the ground in a disaster came after a friend was killed in the Sri Lanka tsunami. She said she felt “compelled to go.” She raised money through her college classmates. Professor Lightburn recalls it as a harrowing time for her as a mother, particularly after Kara told her that gun-toting rebels greeted her at the airport.

“I called colleagues who assured me that the areas where she was going were not too violent,” Professor Lightburn said. “When she called me later she was helping rebuild a fishing village and she said, ‘I’ve never been happier in my whole life.’”

After the earthquake in Haiti, Kara Lightburn had to go beyond helping people attain basic needs, like shelter, food, and water. She also had to arrange security for women and children who were being raped amid the chaos. Among the victims was a 4-year-old girl.

“We worked with the camp leaders and organized security committees,” she said. “We also made sure the victims knew that we would pursue every line of justice for the perpetrators.”

Kara Lightburn said that while her mother’s work differs from her own, each one’s work boils down to strengthening communities.

“Community is community. It’s the same if it’s international or local,” she said.

“The other thing we absolutely share is the belief in the dignity of everybody,” said Professor Lightburn. “We’re really not that different; each of us brings different gifts.”

“But the number one thing we do in both of our professions is listen to people and walk with them,” said Kara Lightburn.

“And act with them,” added Professor Lightburn.

]]>On Tuesday, Dec. 15 at 6 p.m., Fordham will host a panel discussion on the many legal issues that have exacerbated the crisis, its human rights implications, and its humanitarian imperatives.

Dominicans of Haitian ancestry have been pouring over the border into Haiti since 2013. That’s when the Dominican government ordered that all Dominican Haitians must prove Dominican lineage with ancestral birth certificates dating from before 1929, or be expelled.

“An estimated 200,000 people are at risk of being rendered stateless,” said Marciana Popescu, PhD, an associate professor in the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS).

Popescu said that birth certificates aren’t issued as rigorously on the island as they are in the United States. She said that the timelines for appeal were rigid and the process was not clear. Lack of information, in some cases, and low literacy levels in other cases, plus the difficulty of obtaining proper identification explained the decision of many to not challenge the Dominican laws.

In August, Popescu visited Haiti at the invitation of Fordham student Kara Lightburn and saw the crisis firsthand. Lightburn is earning her master’s degree from the University’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs (IIHA), and simultaneously spending time on the ground in Haiti. In 2010, she founded Social Tap, a New York-based nonprofit providing services through Haitian partnerships. The group is assisting Popescu with research on the refugee camps forming at the border.

The two women will present an assessment of findings next week.

The ambiguities created by the new laws, the political tensions, and the limitations of international definitions of refugees further complicate this situation. In the absence of a refugee status, no official refugee camps were set up. The haphazard arrangement has left the displaced population living in flimsy tents partially covered with tarps vulnerable to the elements.

“The rain comes in through top and bottom,” said Popescu. “The day after I left, the entire camp was flooded.”

Several people have already died of cholera, she said, since the refugees were not educated on the dangers of drinking untreated water.

While the Dominican Republic has not officially started deportation proceedings, Popescu’s research has shown that an overwhelming 86 percent of Dominican Haitians are returning to Haiti “spontaneously.” Additionally, the military and police have been routinely putting people in cars, taking them to the border, and leaving them there.

The refugees are heading to a country experiencing over 70 percent unemployment, so getting them out of the camps and integrated into the society will not be easy, she said. Further complicating the situation is that the tiny nation is in the midst of a national election.

“Until there is a new government, it’s not clear who is responsible for what,” she said. “One thing is certain, people want to move out of the camps. And while they believe that either the Haitian government or the international organizations should take responsibility, they don’t put much trust in either… and with the ongoing elections, they are left waiting. And for some, especially the infants and the elderly at camp, time is running out.”

The event is being co-sponsored by the IIHA, GSS, and the Leitner Center for International Law and Justice.

]]>

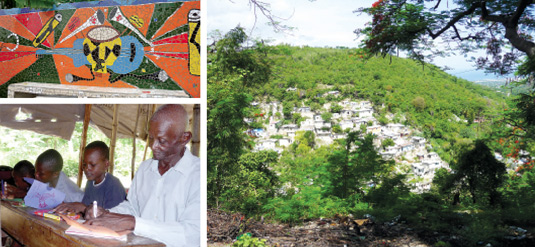

Marciana Popescu, Ph.D., associate professor of social work in the Graduate School of Social Work (GSS), spent 10 days in Haiti this past summer with five current and former GSS students. In addition to exploring the sometimes-overlooked beauty of the island nation, the Fordham contingent visited with groups that are overseeing reconstruction efforts.

Marciana Popescu, Ph.D., associate professor of social work in the Graduate School of Social Work (GSS), spent 10 days in Haiti this past summer with five current and former GSS students. In addition to exploring the sometimes-overlooked beauty of the island nation, the Fordham contingent visited with groups that are overseeing reconstruction efforts.

Over the past four years, Fordham groups worked closely with two grassroots organizations in Haiti – Social Tap, and Konbit Pou Ayiti (“Working Together for Haiti”) which hosted the groups and coordinated all field work in Cyvaddier and Jacmel, Haiti.

Some projects they examined are underway or have been completed, such as the foundation of a new school for which Fordham students together with Social Tap’s director and staff raised $5,000. Popescu’s group also took on a new role, working in close collaboration with an orphanage coordinator to develop a strategic plan for both immediate and long-term sustainability. They conducted a follow-up study of one population that had been relocated after the earthquake in Jacmel, in collaboration with Social Tap and a local consultant.

That study led to the organization of a conference to be co-hosted by Fordham and the United Nations on Saturday, Nov. 16 at the Lincoln Center campus. (For information email [email protected].) This conference will establish a forum for the Fordham community to initiate a dialogue with UN agencies, international development partners, grassroots organizations, as well as the Haitian community in Haiti and abroad. For additional Fordham-sponsored events on Haiti, see The Haiti Experiment.

— Contributed photos

(Right) Tania Bailon, GSS ’13, current student Bridgette Ames, Michelle D’Addio, GSS ‘13, Nancy Lucashu, GSS ’12, Ilene Richman, GSS ’13, and faculty member Marciana Popescu (rear center) visiting KOFAVIV, an organization focused on women’s rights and fighting violence against women in Haiti.

Haiti’s Slow Path to Recovery

Since the 2010 earthquake that devastated Haiti, recovery efforts have included rebuilding, reforesting, redevelopment, and infusions of foreign aid and global agribusiness. But are these endeavors actually helping Haitians to take charge of their own destiny?

This month, Fordham University will host two high-profile events spotlighting development in the tiny island nation that is still struggling to recover and grow.

See Upcoming at Fordham: The Haiti Experiment for more information on this semester’s Gannon Lecture.

]]>

As Haiti passes the third anniversary of the earthquake, thousands of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have been motivated to help solve Haiti’s many recovery problems, including how to best serve its disabled community.

In the face of many disparate initiatives, ultimately it falls the central government to develop policy and monitor the activities of NGOs, said Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Economics and Fordham’s Center for International Policy Studies.

“The earthquake led to injuries and trauma, leading to more physical and mental disabilities,” said Mitra.

In an attempt to address the needs of the disabled, Gerald Oriol, Jr., was appointed Haiti’s secretary of state for the integration of persons with disabilities in 2011. Oriol, who has a disability, promptly set about redefining perceptions and collecting new data on disability via the country’s official census, set to take place later this year.

The secretary has tapped Mitra, a specialist in the economics of disability, to help hone the census questionnaire and advise on policy.

Mitra has advised that language thus far drafted in the census, which before framed disabilities as “impairments,” to be recast as “limitations on functionings.”

She has been involved in the drafting of new questions based on research from the Washington Group on Disability Statistics. A question like “Do you have difficulty seeing, even if wearing glasses?” could be answered with, “No – no difficulty,” “Yes – some difficulty,” “Yes – a lot of difficulty,” or “Cannot do at all.” The more nuanced a survey is, she said, the greater assurance that more than just the extreme cases make it onto the record.

Mitra said that disability biases are not limited to Haiti.

“Whether in high or low income countries, negative attitudes with respect to what people with disabilities can do are still common. But in high income countries, progress has been made on the physical aspects of integration,” she said.

While cities like New York have highly visible accommodations for persons with disabilities, developing countries have more limited resources to adapt infrastructure.

“There are the physical aspects of integration and accessibility, but then there are the social attitudes that act as barriers,” said Mitra. “Fighting the biases will affect people’s likelihood of being successful. It needs to be about physical access and social access.”

Mitra’s Haiti experiences will find their way back into Fordham’s classrooms.

“My work so far has been primarily in producing research and this is a good way to show students how research can practically influence policy,” said Mitra.

]]>

Prior to the global economic crash of 2008, many nations faced a crisis of a different sort—a food crisis—brought on by a worldwide spike in the prices of commodities like corn, wheat, and rice. Haiti was one of the countries particularly hard hit. In the spring of that year, many Haitians starved even though they were surrounded by rice. Imported rice.

For Steven Stoll, Ph.D., associate professor of history, the situation was perplexing.

“I knew that Haitians had produced a very distinct kind of rice that they were extremely proud of,” he said. “Where was that rice?”

According to Stoll, policies established by the International Monetary Fund created a situation in which Haitian rice became more expensive than imported rice—in effect, forcing Haitians to abandon their domestic farmers for engagement in, and dependence on, the global market.

It was a move designed to “modernize” Haitian society by turning the people into wage earners who could purchase goods. Stoll, however, questions the notion that traditional agrarian societies need such modernization, given the often dismal results it produces, as exemplified by Haiti.

“Haiti once had a thriving countryside,” he said. “What happened to it? All of these people now lived in the bidonvilles—in the slums. How did they get there? It was the entrance for me into asking the larger question of how agrarian people become dependent.”

The plight of agrarian societies is the central focus of Stoll’s research, and he is currently at work on a book titled Outliers and Savages: The Ordeal of the Agrarian Household in the Atlantic World.

“More people have been members of agrarian households than any other class in human history,” said Stoll. “Yet these people have been under siege in the last 200-300 years all over the modernizing world.

“I’m interested in how they hung on, how they were undermined, the resistance they put up, and ultimately, I’m interested in whether or not this model should be regarded as a possible route for economic development. Perhaps instead of dispossessing agrarians, development agencies should be working to strengthen them and make it possible for them to do what they do better: grow and sell their garden and field crops without industrializing them or turning them into wage workers.”

In tracing a history of agrarian households in North America, Stoll looks to the Appalachian societies that first populated the forested mountains of western portions of Pennsylvania and Virginia, which, at that time, marked the nation’s frontier. In the period after the Revolutionary War, this “American peasantry,” as Stoll refers to them, were extraordinarily adept at thriving in a harsh landscape that was undesirable to landowners grabbing up fertile bottomland. They were also able to maintain their economic independence from the burgeoning nation-state.

According to Stoll, such independence rankled Federalists like Alexander Hamilton, who tried to force Appalachians to pay a tax on rye whiskey, thus provoking the Whiskey Rebellion of the late 18th century.

“If you’re not paying taxes, then you’re not part of the economy,” said Stoll, in summing up Hamilton’s position. “And if you’re not part of the economy, you’re not a citizen,” he continued.

Stoll emphasizes, however, that Appalachians also engaged in vigorous trade and bought the things they desired but couldn’t make themselves.

“That didn’t mean that they bought and sold everything in their lives, turned everything into a commodity, including their own labor,” he said. “The market was something that they chose—not something that they were compelled to. They could buy and sell because it was opportunity, because it was enticing.”

Though the Appalachians stood up to Hamilton and did

not pay the Whiskey Tax, they later succumbed to other pressures when the desire grew for natural resources on their land—namely, timber, metals, minerals, and eventually coal. When wealthy landowners gained control of their land and cut down their forests, Appalachians were forced to seek work as coal miners and became dependent on wages. Their agrarian society collapsed.

To outsiders, the move from agrarianism to market dependence may signify a positive shift away from outdated practices toward modernization. Stoll, however, attributes this view to

a theory developed by 18th-century Scottish philosophers, particularly David Hume and Adam Smith, who conceptualized human society as naturally progressing through sequential stages from hunting, herding, and farming, to a commercialized division of labor.

“There’s no evidence for this [theory]whatsoever,” said Stoll. “Yet it influenced the way people in the West looked at economic development for centuries . A lot of people look at how we live as the outcome of a process of social evolution that says that this is the best of all possible worlds. But that view invalidates the way billions of people live by defining them as backward.”

Stoll sees proof of the continuing value of subsistence food production in places like Uganda, where, despite political problems, there is a “thriving food producing peasantry,” which produces so much food that some of it is exported.

“It’s a very unusual situation in which the government actually derives GDP import dollars from a non-capitalist sector of production,” he said. “They more than feed themselves. Far from starving, they’re thriving.”

]]>Such was the sobering news delivered on Feb. 23 at the Lincoln Center campus. “Haiti: One Year Later,” a panel presented by the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs, featured unvarnished assessments of the steep challenges that aid groups face in rebuilding the country.

Speakers included Gerald Martone, director of emergency response at the International Rescue Committee; Anne Edgerton, policy, advocacy and media lead for Oxfam International in Haiti; Russell Porter, coordinator of the USAID Haiti Task Team; Robin Contino, deputy coordinator for Catholic Relief Services; and Matthew Cochrane, communications coordinator for Haiti at the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

Martone called the situation in and around the capital city of Port-Au-Prince, where an estimated 222,000 people died, a perfect laboratory for the disaster of the future.

“This is a biopsy of the megatrends we’re going to face: urbanization, high population density in an urban area, the effects of climate change, global economic deceleration, water scarcity, overpopulation, food scarcity, energy scarcity—it is all there in Haiti,” he said.

With that in mind, Martone suggested that aid groups change their perspective from one that assesses the needs of communities affected by disasters to one that assesses capacities they bring to the recovery effort.

“We really seem to forget that there’s no society in the world that doesn’t have some form of indigenous altruism. People come together quickly after disasters and actually rally and do take care of themselves,” he said. “Most of the rescue work in disasters is done by the communities themselves.”

Edgerton contrasted Haiti’s situation to recent disasters such as the Asian tsunami in 2004 and the 6.8 magnitude earthquake in Kobe, Japan in 1995. Even in a well-functioning country like Japan, it took a year to formulate a recovery plan for Kobe and another seven years to complete it.

In Haiti, she noted that the recent outbreak of water-borne cholera was particularly demoralizing for Oxfam, since clean water is an integral part of its mission.

“If you look at cholera that broke out in the tenth month after the earthquake and then the political violence and the lack of resolution during 2010 the elections, it’s almost a case study that no one would believe,” she said.

Cochran pointed out that understanding the problem of rubble removal requires great imagination for anyone who’s never been to Port-au-Prince. The United Nations estimates that there is 10 million cubic meters of rubble that needs to be cleared from the city and the surrounding areas. Even if it were accessible by digging equipment, which it is not, the average truck can only carry nine cubic meters of rubble.

“It would take Haiti’s estimated 300 trucks—working seven days a week—more than five years to ship the rubble to the one dump site that exists,” he said. “There are also no laws that provide clarity on who owns the rubble. Authorities can’t decide whether the rubble belongs to the state, the owner or to the person who rents it out. So the rubble that can’t be moved just sits there.”

Despite the gloomy forecast, panelists cited some bright spots. Contino, for instance, touted CRC’s “Rubble to Reconstruction” project, which provides tools for Haitians to pulverize small pieces of rubble in otherwise inaccessible areas of Port-au-Prince.

“We’ve allowed people to stimulate their own livelihoods, because with the rubble they crush, they’re able to sell that. We’re one of the agencies that buys that concrete to make foundations. So these individuals are able to earn and use that rubble to rebuild their homes,” she said.

]]>Wednesday, Feb. 23

5:30 p.m.

12th Floor Lounge

Lowenstein Center

Lincoln Center campus

“Haiti: One Year Later,” a panel presented by the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs, will feature speakers Gerald Martone, director of emergency response at the International Rescue Committee, Anne Edgerton of OXFAM, Russell Porter, Coordinator, USAID Haiti Task Team and Robin Contino, Deputy Coordinator for Catholic Relief Services.

For more information, RSVP at [email protected]

]]>Speaking at the Rose Hill campus, Archbishop Bernardito Auza painted a bleak picture of the situation in Haiti. He detailed the short- and long-term problems faced by its citizens, as well as the imminent threat caused by disease.

Since hearing the address, which was held over lunch at the McGinley Center on Nov. 19, students and Global Outreach organizers have decided to postpone the trip. The idea will be revisited when the threat of cholera has decreased and there is more stability throughout the country.

Archbishop Auza began by giving the audience a sense of the nation, which he said is very small on the international scene, but looms large in the region as its third-largest country.

Even before the earthquake on Jan. 12, Haiti had suffered from a 30-year decline and was basically run by non-governmental organizations, he said.

The poorest nation in the Western hemisphere, its annual per capita income was $60. Its $6.5 billion gross domestic product is supported by $1.7 billion in remittances—money sent back to Haiti from citizens living abroad.

In the 11 months since the 7.0-magnitude earthquake, the international community has raised $11.5 billion for Haiti. But because the country was awash in corruption before the disaster, there were no reliable local authorities with which relief organizations could work. That has held up redevelopment, Archbishop Auza said.

“Most of that money goes to support basic human necessities, so I’m afraid you won’t see any buildings being built,” he told the students.

The archbishop said that people who judge Haiti’s prospects only by how much money has been earmarked for relief do not understand that there is no toehold from which to built a better society.

“It is very sad and insulting that people say the best thing that happened to Haiti was the earthquake,” he said.

For example, although education takes up roughly 40 percent of the average family’s meager budget, anyone with skills routinely leaves the country. The Catholic Church runs 36 to 40 percent of the nation’s schools, but because the system is entirely dependent on tuition, this past year has been especially difficult.

Catholic higher education has been set back even further. The University Notre Dame of Haiti has been closed since the earthquake, which devastated the university’s foundation and forced the cancellation of all classes.

“Nowhere was there one single, temporary classroom,” Archbishop Auza said.

Lawlessness is also endemic in Haitian society, he said. There is no military, only about 2,500 national police officers—about 30 percent of whom are linked to organized crime.

In addition to social problems, the nation’s natural environment has been severely degraded. Only 2 percent of the total land mass remains covered with vegetation, according to the archbishop.

“Ninety-five percent of Haitians use charcoal for cooking,” he said. “But if five million trees are planted, 25 million are cut. The charcoal being used in Haiti today is not from mature trees—only young trees.”

Infrastructure woes continue to affect the capital city, Port au Prince, which can fulfill only 15 percent of its energy needs. On the streets, water is sold off a truck for much more than the average citizen can afford.

Archbishop Auzen said the only way forward for Haiti is for relief agencies and other nations to cultivate local partners who are reliable. But he said that process will take some time.

“You have to trust your local partners, but they have to merit that trust.”

Also in attendance at the luncheon were representatives from Fordham’s graduate program in International Political Economy and Development, Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs and Fordham Law’s Feerick Center for Social Justice.

—Joseph McLaughlin

October 13, 2010

Haiti Relief: Nine Months Down

Since a devastating earthquake struck Haiti on Jan. 12, the Fordham community has donated $51,787 to relief efforts—and helped propel a recovery that is only beginning.

With the first anniversary of the quake approaching, 1.2 million people are still displaced, with many living in difficult conditions in temporary camps around Port-au-Prince, according to Catholic Relief Services. Using abundant donations from many sources including Fordham, CRS and Jesuit Refugee Service are working to improve living conditions in the camps, but also turning their attention to long-term recovery in a country that was already impoverished.

“It was the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere before this quake. The quake made it vastly worse,” said Tom Price, spokesman for Catholic Relief Services. “We’re not going to solve Haiti’s problems overnight.”

Fordham sponsored many events to spread awareness of Haiti’s plight and raise funds for rebuilding and relief efforts. The donations were evenly split between Catholic Relief Services and Jesuit Refugee Service, both of which have low overhead costs and were working in Haiti prior to the quake.

Both organizations used the donated funds to provide food, medical care, temporary shelter and many other immediate forms of aid in the aftermath of the quake, which struck just outside the capital, Port-au-Prince. Jesuit Refugee Service has delivered food to more than 50,000 people throughout the city, medical treatment to more than 4,500 injured, and camp management services and psychosocial support to 230,000 people in the seven camps where it has a presence.

Working with Caritas Haiti, Catholic Relief Services provided shelters to more than 256,000 people, supported nearly 1,000 surgeries at St.Francois de Sales Hospital, provided outpatient consultation to more than 69,000 people, installed 680 latrines and bathing spaces and registered 1,863 children to attend child-friendly areas in camps at least three times per week. CRS has also registered 339 unaccompanied children for family tracing and reunification services.

Now, with plenty of donated funds remaining, both organizations are tackling the greater challenge of fostering a sustainable recovery, one that involves Haitians and gives them a leading role in rebuilding the country. At the time of the quake, Haiti was already beset with extreme poverty and high unemployment, along with food shortages stemming from a degraded environment and severe soil erosion, according to Catholic Relief Services.

Through a cash-for-work program, CRS is hiring Haitians to clear rubble and providing tools such as wheel barrows, pick axes, helmets and sledgehammers. Others are paid to perform maintenance work in camps or build transitional, semipermanent wooden homes. CRS has started workingon 2,000 homes and plans to build 8,000, Price said. Its other efforts include a pilot recycling program in one of the camps to help its residents generate income. Also, the organization is providing food to children in 270 schools and more than 100 orphanages.

Meanwhile, Jesuit Refugee Service is preparing to direct funding to long-term recovery projects such as agricultural improvements, or perhaps microcredit programs, that promote economic self-sufficiency, said Christian Fuchs, spokesman for Jesuit Refugee Service USA. JRS is also starting schools in camps, and is working with Fe y Alegria, a Latin American Jesuit school system, to restore damaged schools or build new ones. Jesuit Refugee Service is working on 17 schools at the moment, Fuchs said.

Students who are educated now will be able to rebuild their country later, Fuchs said. “It gives them that sense of empowerment,” he said.

Both organizations have received generous support for their work in Haiti. Jesuit Refugee Service has raised $1.75 million and spent $400,000 so far, Fuchs said. CRS has already raised $140 million toward its five-year goal of $200 million.

While fundraising is less urgent at the moment, it’s important for people to stay engaged with the needs of Haiti and other poor countries over time, Price said. He noted the importance of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals, an anti-poverty initiative. Catholic Relief Services has resources onlinefor schools and parishes, such as prayers, lesson plans, solidarity activities and special reports on the recovery, along with an online gift catalog through which people can target their support to some of the areas of greatest need: health care, shelter, food and jobs, child protection, or clean water and sanitation.

“Thanks so much to Fordham for their support. It’s hugely valuable,” Price said. “We wouldn’t be doing this work down there without the enormous support from the Catholic constituency, including Fordham.”

Founded in 1841, Fordham is the Jesuit University of New York, offering exceptional education distinguished by the Jesuit tradition to approximately 14,700 students in its four undergraduate colleges and its six graduate and professional schools. It has residential campuses in the Bronx and Manhattan, a campus in Westchester, the Louis Calder Center Biological Field Station in Armonk, N.Y., and the London Centre at Heythrop College in the United Kingdom.

—Chris Gosier

Haiti Relief Fundraising Tops $50,000

As of May 12, 2010, the University has raised $50,031 to benefit the victims of the earthquake in Haiti. The funds will be split evenly between Catholic Relief Services and the Jesuit Refugee Service, both of which have low overhead costs and had personnel on the ground in Haiti prior to the earthquake. This amount does not count electronic donations made directly to the two charities. (See “Relief Funds” below for ways to give.)

“Once again, the Fordham family has responded to catastrophe with an immediate and unstinting outpouring of support for the affected souls and their families,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “I am proud, if unsurprised, by the generosity and compassion of the University community in response to January’s devastating earthquake in Haiti. While much still needs to be done for that country and its long-suffering people, I am very pleased to note that Fordham students, faculty, alumni, staff and parents have reaffirmed their commitment to being men and women for others.”

The Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) is focusing its current relief efforts in the Port-au-Prince area, working in seven camps that serve the needs of more than 21,000 displaced people in and around the capital. JRS is also helping to insure the international community includes Haitian voices in the planning for rebuilding of Haiti, planning which should be guided by the principles of respect for sovereignty, self-determination and dignity of peoples. Catholic Relief Services (CRS) s helping to provide food, water, sanitation and shelter in Haiti.

Since the earthquake, Fordham has sponsored a wide variety of fundraising and educational events to aid the people of Haiti and inform the University community—and the public—of the disaster’s scale and continuing effects. Students and student government took a leading role in scheduling bake sales, dances and other club activities to benefit the people of Haiti. The University also raised funds through collections at mass, concerts, library fines and theatre program inserts.

Relief Funds

The quickest and most efficient way to help the Haitian people is to fund organizations already providing humanitarian assistance in that country. Fordham University is accepting donations on behalf of Catholic Relief Services and the Jesuit Refugee Service, both of which already have workers on the ground in Haiti. Cash and checks may be deposited with Thomas A. Dunne, Fordham’s Haiti relief coordinator. All proceeds will be divided equally between Catholic Relief Services and the Jesuit Refugee Service. Secure credit card donations directly to those organizations can be made via the links below.

Please make checks payable to Fordham University, and note “Haiti Crisis” in the memo section:

Thomas A. Dunne, Vice President for Government Relations and Urban Affairs

Fordham Haiti Relief Coordinator

[email protected]

(718) 817-0180

Campus Address:

Administration Building (South), Rm. 112

Rose Hill Campus

Mailing Address:

Thomas A. Dunne, Vice President

Government Relations and Urban Affairs

Fordham University

441 East Fordham Road

Bronx, NY 10458

Thank you for your generosity to date, and for your continued support for the people of Haiti.

May 6, 2010

Fundraising Update

As of May 6, 2010, the University has raised $47,870. This does not count electronic donations made directly to Catholic Relief Services and the Jesuit Refugee Service. (See “Relief Funds” below for ways to give.)

April 26, 2010

Luncheon Discussion: A Day to Remember Haiti

The Fordham Kiwanis are sponsoring a luncheon featuring Haitian food and a presentation by three Fordham Law School students, who went to Haiti during spring break to help at a camp for orphans. The Fordham Kiwanis will award a scholarship to a Fordham freshman from Haiti. A donation of $10 is suggested for the luncheon. Pre-registration is required.

Tuesday, April 27, 2010 | 12:30 p.m.

Faculty Lounge, McGinley Center, Rose Hill campus

Contact: Sister Anne-Marie Kirmse, O.P. (718) 817-4746, [email protected]

April 18, 2010

Fundraising Update

As of April 18, 2010, the University has raised $45,844. This does not count electronic donations made directly to Catholic Relief Services and the Jesuit Refugee Service. (See “Relief Funds” below for ways to give.) Of the total, $22,504 has come from student fundraising, including club activities such as bake sales, raffles, concerts and donations solicited at previously planned events.

Fordham Theatre Program Solicits Haiti Funds

The Theatre Program is placing Haiti relief flyers and donation envelopes in programs for all Studio and Mainstage shows. For information and tickets, see the Theatre Program schedule.

Haitian Film Series

The Department of African and African American Studies and Molimo sponsored films about Haiti this month, including:

Égalité for All: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution, on April 13. The film chronicles the only successful revolution by enslaved people, and the ideas that revolution unleashed. A PBS film directed by Noland Walker, produced by Patricia Aste and narrated by Edwidge Danticat.

The Road to Fondwa, screened on April 15. The film challenges the status quo of international development aid and seeks to inspire a new development model based on the strong partnership between the people of Fondwa, Haiti, and members of the international community. Directed by Justin Brandon and Dan Schnorr and produced by Justin Brandon and Brian McElroy.

April 12, 2010

Lecture: Pierre Toussaint: Journey to Sainthood

Speaker: Camille Brown, Ph.D., of the Archdiocese of Providence. Sponsored by Campus Ministry.

Tuesday, April 13 | 7 p.m.

University Commons, Duane Library, Rose Hill campus

April 7, 2010

Fundraising Update

As of April 7, 2010, the University has raised $43,897. This does not count electronic donations made directly to Catholic Relief Services and the Jesuit Refugee Service. (See “Relief Funds” below for ways to give.)

Choir Concert Benefits Haiti

The Fordham University Choir will perform Art and Architecture in Concert for Haiti, the proceeds from which will go toward Fordham’s fundraising for Haiti relief efforts. The concert features music and words celebrating the beauty of the Fordham University Church.

Sunday, April 11 | 3 p.m.

University Church, Rose Hill Campus

Free Admission | Donations Encouraged

Fordham Libraries Donate Fines

Fordham University Libraries (Lincoln Center and Rose Hill) will donate half of library fines collected toward the Fordham University relief efforts to help the Haitian people. Half of all the money collected for fines will be sent to the Catholic Relief Services and Jesuit Refugee Services. The other half will go toward the purchase of books and materials for the library. Those who do not have library fines to pay but would still like to contribute, may make donations. Contact: Robert Allen at Lincoln Center: (212) 636-6058 or John D’Angelo at Rose Hill: (718) 817-3573.

Conference Touches on Haiti Finances

Jovis Wolfe Bellot, Ph.D., GSAS ’02, a consultant for Haiti’s central bank and a professor of economics at State University of Haiti, said at Fordham’s second annual Migration and Microfinance Research Conference that remittances from migrant workers living abroad made up 25 percent of the Haitian GDP in 2009, and that some 1.1 million Haitians receive remittances on a regular basis, amounting to $1.6 billion last year. See Fordham Notes: “Remittances to Haiti Are Critical.”

Faculty Publication on HaitiSteven Stoll, Ph.D., visiting associate professor of history at Fordham, published “Toward a Second Haitian Revolution,” in the April 2010 issue of Harper’s magazine.

March 12, 2010

Residence Halls Association Auction Raises $14,000

The Residence Halls Association (RHA) Haiti Relief Auction at Rose Hill on March 5 raised $14,244 for Haiti relief, according to president Michael Trerotola.

The auction was only one event in a series during Benefit Week, Trerotola said, and last year the entire week raised a little over $13,000. This year Fordham students opened their wallets to the tune of $18,285 to benefit six charities, including Haiti relief.

Over the course of the week, more than 600 students attended events, Trerotola said.

Courses Offer Haiti History, Background

Caribbean Literature

Haitian literature and literature about Haiti is featured in a major way in the course; but it is also a survey of the literature of the region. It’s an elective, so students are usually literature majors of one kind or another–a level of familiarity with literary scholarship, or how to do literature is assumed.

AFAM-3667 | L01 | CL | 11729 | MW | 11:30 a.m. – 12:45 p.m. | Mustafa, Fawzia | TBA | 30 | 0 | 30

The Caribbean

This course is a history ofthe Caribbean and will include significant discussion about Haiti.

HIST-3975 | L01 | CL | 11637 | MR | 4 p.m. – 5:15 p.m. | Schmidt-Nowara, Christopher E | TBA | 35 | 0 | 35

March 2, 2010

A Haiti Relief Auction, sponsored by the Residence Halls Association, will be held on Friday, March 5, 2010.

Haiti Relief Auction

Friday, March 5, 2010 | 7 p.m.

O’Keefe Commons, O’Hare Hall, Rose Hill Campus

Contact: Michael Trerotola at [email protected], or CassieSklarz at [email protected].

Also, see today’s article, “GSS Event Focuses on Needs of Haitians in Crisis and Beyond,” by Janet Sassi.

February 26, 2010

Haiti Benefit Concert

On Saturday, February 27 at 8:00pm in the McGinley Ballroom and Campus Center Lounge the Fordham community will again come together to host the Haiti Benefit Concert. The concert will showcase Fordham talent including the B-Sides, Expressions Dance Alliance, Fordham Flava, CSA’s Fordham Idol champion, the Ramblers, the Satin Dolls, and the University Choir; in addition, the Office of Multicultural Affairs, the Dorothy Day Center for Service and Justice and ASILI will provide educational information about Haiti’s very unique history. There will be a suggested entry donation of $5 which will include entrance, beverages, a “Taste of Arthur Avenue” as well as contributions from Sodexo. CAB’s Cultural Affairs committee will be hosting a ticket raffle for Jersey Boys, Wicked, the Rangers and the Knicks, each person will receive one raffle ticket when they enter the event and there will be more available for purchase.

Office of Student Leadership and Community Development

Contact (718) 817-4339, [email protected]

February 19, 2010

Fundraising Update

As of February 19, 2010, the University has raised $20,468. This does not count electronic donations made directly to Catholic Relief Services and the Jesuit Refugee Service.

Community Leaders to Share Knowledge About Empowering Haiti

Community leaders from New York City and beyond will discuss ways to support Haiti in the wake of its recent tragedy.

“United for Haiti: Compassion in Action” seeks to be a catalyst for continued support of the nation and its people through advocacy, volunteerism and program development.

Saturday, Feb. 27

7 to 10:30 p.m.

Church of St. Paul the Apostle

West 59th Street and Columbus Ave.

New York City

Speakers at the event will include:

• Joel Dreyfuss, founder of the National Association of Black Journalists

• Bill White, ambassador to the Council of Friends of FOKAL

• Rosmonde Pierre-Louis, deputy Manhattan borough president

• Jeff Gardere, psychologist and director of the Harlem Family Institute

• Bishop Guy Sansaricq, auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of Brooklyn and co-founder of Haitian-Americans United for Progress

This event is sponsored by the Graduate School of Social Service at Fordham and Office of Campus Ministry, as well as the Institute for Women and Girls and several student groups.

Free and open to the public. Donations and emergency relief supplies will be collected and refreshments will be served.

Please click here to download a pdf flyer about the event, including information about which emergency relief items are best to donate.

February 8, 2010

A division of the Graduate School of Education is helping to establish a newcomer center in Rockland County, N.Y, for children who are victims of the Haitian earthquake.

The school’s Lower Hudson Valley Bilingual ESL Teaching Assistance Center (BETAC), housed at Fordham Westchester, is working with the East Ramapo Central School District to plan a curriculum for the center and train the instructors who will work there.

The Spring Valley/East Ramapo area of Rockland County is home to the largest Haitian community in New York outside of New York City.

“East Ramapo has already absorbed 52 new Haitian students as of Feb. 4,” said Carol E. Pertchik, director of the New York State Lower Hudson Valley BETAC. The district estimates that the devastation in Haiti will result in 150 to 200 new students in the coming months.

The center will organize the students into four groups based on age and expected grade level—Kindergarten through second grade, third through fifth grades, sixth through eighth grades and high school.

“The newly arrived students will have similar needs,” Pertchik said. “The center will create a sheltered experience where they can acclimate to their new environment through counseling sessions—at least one per day—as well as language instruction and a strong academic program.

“It’s a three-pronged approach,” she said.

As the new students become more comfortable with the school system, they will be integrated into regular classes.

East Ramapo superintendent Ira E. Oustatcher, Ed.D., is spearheading the initiative. He is relying on BETAC to help develop the program materials and train instructors at the center and those in the regular classrooms.

BETAC, which is part of the Center for Educational Partnerships at Fordham, provides technical assistance and professional development to schools in Rockland, Putnam and Westchester counties in New York.

Diane Howitt, a resource specialist at BETAC who speaks Haitian, is attending a parent meeting in East Ramapo on Feb. 8 to determine other ways her group can aid the effort.

“Basically, she’s there to find more entry points for us to provide additional support,” Pertchik said.

Founded in 1841, Fordham is the Jesuit University of New York, offering exceptional education distinguished by the Jesuit tradition to approximately 14,700 students in its four undergraduate colleges and its six graduate and professional schools. It has residential campuses in the Bronx and Manhattan, a campus in Westchester, the Louis Calder Center Biological Field Station in Armonk, N.Y., and the London Centre at Heythrop College in the United Kingdom.

January 28, 2010

Faith and Public Policy Roundtable, Statement on the Crisis in Haiti

The earthquake in Haiti has not merely hurled the people of Haiti into profound pain and loss. It has placed in bold relief the unrelenting plight endured by the people of this poverty-stricken nation. Such disaster begs a question of the gravest sort: where is God in Haiti’s desolation and grief?

Some religious leaders have answered this question by claiming divine punishment of the Haitian people and calling for mass repentance for some aggravating sin. We utterly repudiate this position. It is erroneous and misleading.

We are Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish clergy and academics, and we share the Psalmist’s conviction that “God is our refuge and stronghold, a help in distress, very near. Thereforewe are not afraid though the earth reels, though mountains topple into the sea—its waters rage and foam; in its swell, mountains quake.” We believe God is near to the Haitian people who have endured such terrible loss and devastation.

Human temptation finds the judgment of a vicious God in natural disaster. Contrary to that impulse, people of faith put their hope in a God who loves and worries for humanity. It is up to us: men and women of flesh and blood created in the Divine image, holding in our hands the redemptive power of our human responsibility, to provide direction in reaching for God’s nearness. As Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik wrote regarding the worst of human suffering, ultimately “We ask not about the reason for evil and its purpose, but rather about its rectification and uplifting.”

Identifying God as being very near to those who suffer places responsibility squarely on the shoulders of all humanity. The impact of this disaster and its toll on human life, both those so cruelly taken and those who struggle daily to survive, is at once borne acutely by a particular people and the concern of us all.

As a non-fundamentalist interfaith roundtable concerned with religious values that address public policy concerns, we urge our country, both its private and public sectors, to provide two forms of aid to Haiti: the kind of emergency support most needed now, and already being provided by so many individuals and organizations, and then, the harder kind of aid to maintain: that which will provide for sustainable recovery. This means we are committed to reconstruction of Haiti over the long term. As human beings created in the Divine image, we must stay near to this people in their need just as God remains close. We urge the faithful of our country to act with such bold resolution.

Acts of faith are the incremental building blocks of healing and justice. In this case we begin by acknowledging that we of the developed world have not been near to the Haitian people. We have allowed abject poverty to perpetuate itself far too long. We of the developed world have failed. God’s nearness to those who suffer calls us to constant vigilance that illuminates the Divinity within our humanity. Our aid to Haiti needs to reflect the value of ongoing sustenance. We bear responsibility to lift the burden of poverty by every means possible.

The people of Haiti will have many needs in the months and years to come. Our aid to Haiti must be deep and long in impact, given over to an individual or a community in a sustainable way. Emergency aid will need to be reshaped into support for the rebuilding of lives, institutions and infrastructure.

We urge all Americans to support relief and reconstruction efforts to help Haiti through this crisis, and to think about how each of us, in our own way, individually and through institutions, will continue to support the recovery of Haiti over time.

This tragedy will become multi-generational unless the human family rallies around this stricken nation.

Faith and Public Policy Roundtable

Steering Committee (In alphabetical order)

Noah Arnow

Senior Rabbinical Student, Jewish Theological Seminary of America

Rabbi David Lincoln

Rabbi Emeritus, Park Avenue Synagogue, New York, N.Y.

*The Reverend Gary Mills, Ph.D.

Assistant to the Bishop for Global and Multicultural Administration, Metropolitan New York Synod, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

Rabbi Stephanie Ruskay

National Education Director, Avodah: The Jewish Service Corps

The Reverend Patrick J. Ryan, S.J.

Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society, Fordham University

Henry Schwalbenberg, Ph.D.

Director, Graduate Program in International Political Economy and Development (IPED), Fordham University

The Reverend Jared R. Stahler

Associate Pastor, St. Peter’s Church, New York, N.Y.

*Rabbi Abraham Unger, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor and Director of Urban Programs, Department of Government and Politics & Campus Rabbi, Wagner College

Rabbi, Congregation Ahavath Israel, Staten Island, N.Y.

*Steering Committee Co-chair

The Faith and Public Policy Roundtable is a coalition of mainstream clergy and academics from houses of worship, seminaries and universities, and ecclesiastical organizations throughout New York City. For moreinformation see: Non-Fundamentalist Religious Leaders Confront Economic Crisis

Jan. 22, 2010

Humanitarian crisis experts agree that the best way to help the people of Haiti right now is to donate money to reputable organizations involved in the relief effort. Collections of goods, such as food, clothing and medicine, are well meaning, but do far less to improve conditions in the disaster area than monetary donations. Likewise, traveling to Haiti as a volunteer is probably neither possible nor helpful at this stage of the crisis. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), outlines the very limited conditions under which goods and services might be helpful in Haiti on its website: www.usaid.gov/helphaiti

See the information and links below for ways to donate to relief efforts in Haiti.

Jan. 21, 2010

Credit Card Donations for Humanitarian Relief in Haiti

Members of the University community and friends of Fordham may donate cash and checks to be distributed equally between Catholic Relief Services and the Jesuit Refugee Service as outlined below, or may make secure credit card donations directly to those organizations via the following links:

Thank you for your generosity to date, and for your continued support for the people of Haiti.

Jan. 20, 2010

Dear Members of the Fordham Family,

As of Wednesday morning, the death toll in Haiti is reported to beat least 70,000, and experts expect that number to continue climbing. Everything is in short supply in Haiti in the aftermath of last week’s earthquake, especially the basics: shelter, food, clothing and medicine. I ask you to do whatever you can for the people of Haiti in their hour of urgent need. Below are the University’s plans thus far to help ameliorate the humanitarian crisis.

Sincerely yours,

Joseph M. McShane, S.J.

Relief Funds

The quickest and most efficient way to help the Haitian people is to fund organizations already providing humanitarian assistance in that country. Fordham University is now ready to receive donations on behalf of Catholic Relief Services and Jesuit Refugee Services, both of which alreadyhave workers on the ground in Haiti. Cash and checks may be deposited with Thomas A. Dunne, Fordham’s Haiti relief coordinator. Within 24 hours, the University will have a Web page set up to receive credit card donations. All proceeds will be divided equally between Catholic Relief Services and Jesuit Refugee Service. Please make checks payable to Fordham University, and note “Haiti Crisis” in the memo section:

Thomas A. Dunne, Vice President for Government Relations and Urban Affairs

Fordham Haiti Relief Coordinator

[email protected]

(718) 817-0180

CampusAddress:

Administration Building (South), Rm. 112

Rose Hill Campus

Mailing Address:

Thomas A. Dunne, Vice President

Government Relations and Urban Affairs

Fordham University

441 East Fordham Road

Bronx, NY 10458

Affected Community Members

The University has identified approximately 25 members of the campus community whose families may have been affected by the earthquake. Deans and administrators are reaching out to those individuals to offer whatever support the University can provide during the crisis. If you are concerned about a student affected by the crisis, please contact the Office of Residential Life at (718) 817-3080 (from any campus).

Campus Activities and Community Involvement

Expert Panel: Haiti: Crisis and Humanitarian Action

Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs, moderates a panel on the nature and scale of the disaster in Haiti, and the humanitarian response underway there. Panelists include:

• Paul Browne, New York City Police Department’s deputy commissioner of public information and deputy director of the International Police Monitors in Haiti, where he helped establish an interim police force during the United States-led “Operation Restore Democracy” in 1994-1995.

• Rev. Ken Gavin, S.J., national director of the Jesuit Refugee Service, U.S.A.

• Robert Nickelsberg, American photojournalist whose work often appears in Time magazine, and who was embedded with the First Marine Division in the Iraq War in 2003.

• Ed Tsui, former longtime director of the New York office of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

Thursday, Jan. 21, 1 p.m. | Keating First Auditorium, Rose Hill campus

Free and open to the public

Student Life Council Emergency Meetings

Lincoln Center

Thursday, Jan. 21, 11:30 a.m. | Lowenstein Center, Room 508

All interested students and student leaders are encouraged to attend.

Contact: Keith Eldredge,

Dean of Students

(212) 636-6250

Rose Hill

Thursday, Jan. 21, 3 p.m. | McGinley Center, Faculty Lounge

All interested students and student leaders are encouraged to attend.

Contact: Christopher Rodgers,

Dean of Students

(718) 817-4755

Campus Ministry

Interfaith Prayer Services for Haiti

All members of the University community are welcome.

Lincoln Center

Wednesday, Jan. 20, 2:30 p.m. | Lowenstein Center, Blessed Rupert Mayer, S.J., Chapel (Room 221)

Rose Hill

Wednesday, Jan. 20, 5 p.m. | McGinley Center, McGinley Ballroom (Second Floor)

Holy Eucharist in Solidarity with the People of Haiti

Archbishop Celestino Migliore, Permanent Observer of the Holy See to the United Nations, will be the main celebrant at this Mass for the people of Haiti.

Sunday, Jan. 24, 9 p.m. | University Church, Rose Hill Campus

All members of the University community are welcome.

In addition, collections from the Mass that traditionally accompanies the Fordham Athletics Hall of Fame Ceremony, Saturday, Jan. 23, 9:30 a.m., will be added to Fordham’s Haiti relief funds.

Founded in 1841, Fordham is the Jesuit University of New York, offering exceptional education distinguished by the Jesuit tradition to approximately 14,700 students in its four undergraduate colleges and its six graduate and professional schools. It has residential campuses in the Bronx and Manhattan, a campus in Westchester, the Louis Calder Center Biological Field Station in Armonk, N.Y., and the London Centre at Heythrop College in the United Kingdom.

01/10

Jan. 15, 2010

Dear Members of the Fordham Family,

As you know, this week the Republic of Haiti has been wracked with what is likely to be the hemisphere’s worst humanitarian crisis in our lifetimes. The Red Cross tells us that there are 50,000 dead already in that stricken country, and many, many more people at risk in the aftermath of Tuesday’s earthquake. The scale of the crisis is immense, and its effect on that already poor nation heartbreaking.

The University is mobilizing its response to the catastrophe (indeed in true Fordham fashion, many people have already contacted my office and Campus Ministry, to find out what they could do to help). We are already reaching out to those students, faculty and staff who may have family in Haiti to find out what assistance the University can offer. By next week we will have a dedicated fundraising program in place, the Fordham Fund for Haiti, to channel donations to Catholic Relief Services and Jesuit Refugee Services, both of which already have workers on the ground in Haiti.

As students return from the winter break, the University will coordinate their efforts with those of faculty, alumni and staff, so that our efforts will offer the most benefit to the Haitian people. I have asked Thomas A. Dunne, vice president for government relations and urban affairs, to coordinate the University’s response to this crisis. If you, your department or your student group or alumni chapter would like to help, please contact Tom Dunne at the number and e-mail addressbelow.

As Fordham’s relief efforts gather momentum, we will keep you informed via e-mail and the University’s home page. Until our response to the disaster is fully in place, I invite you to join us in prayer for the people of Haiti, for those who have died, and for their loved ones here and abroad. Campus Ministry has already organized prayer services next week, and will receive collections at Holy Eucharist this Sunday at Rose Hill and Lincoln Center.

Thank you, in advance, for your compassionate response to this humanitarian crisis, and for your prayers on behalf of the people of Haiti and their loved ones.

Sincerely yours,

Joseph M. McShane, S.J.

]]>