Since the 1970s, Fordham students have been studying and contributing to the spirit of innovation and community renewal that has come to define what it means to be a Bronxite.

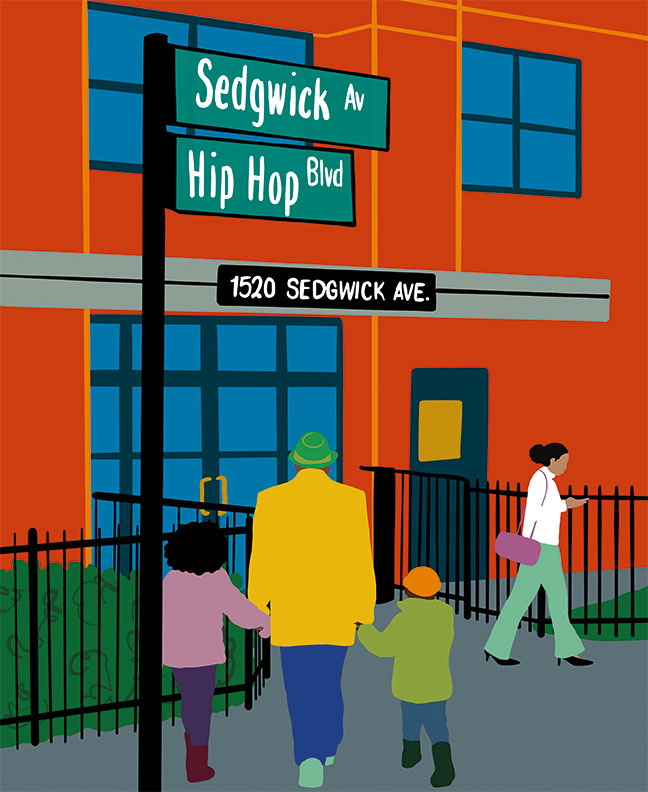

Fifty years ago, a new art form burst forth on the streets of the Bronx, born from rich musical traditions and a spirit of innovation in neighborhoods of color ravaged by deindustrialization and written off by most of the country. In the ensuing decades, the Fordham community has not only studied and celebrated hip-hop as a revolutionary cultural force but also helped preserve its Bronx legacy—through efforts to recognize the apartment building at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue as the genre’s birthplace, and through oral-history interviews with some of hip-hop’s seminal figures.

“I think the lesson is, let’s explore, interrogate, and embrace the cultural creativity of our surrounding areas because it’s unparalleled,” said Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of African and African American studies and founding director of Fordham’s Bronx African American History Project.

Naison teaches a popular class, From Rock and Roll to Hip-Hop, that draws on artists like Cardi B, Nas, and Run-DMC to understand the music and its part in U.S. history—and to explore issues he’s spent his career teaching. “I’m not a hip-hop scholar,” he said. “Rather, I’m someone who works to have community voices heard.”

And just as the music has evolved over the past 50 years, so have efforts to revitalize the borough and tell the stories of its residents.

Challenging ‘Deeply Entrenched Stereotypes’

Amplifying community voices is at the heart of the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). Fordham launched the project in 2002, at the request of the Bronx County Historical Society, to document and preserve the history of Black people in New York City’s northernmost borough. Naison and his team of Fordham students, faculty, and community historians have spoken with hip-hop pioneers like Pete DJ Jones and Kurtis Blow, but the project is much broader: The archive contains verbatim transcripts of interviews with educators, politicians, social workers, businesspeople, clergy members, athletes, and leaders of community-based organizations who have lived and worked in the Bronx since the 1930s. The archive, which also includes scholarly essays about the Bronx, was digitized in 2015, making the interviews fully accessible to the public.

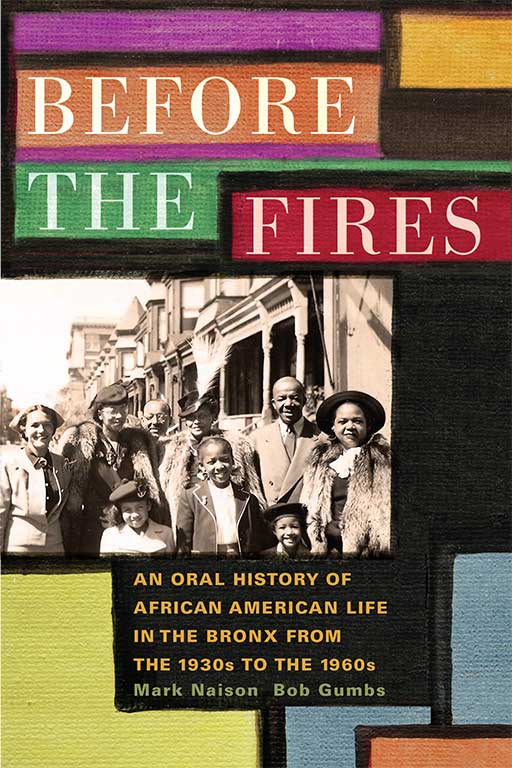

“Starting by interviewing a small number of people I already knew,” Naison wrote in Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life in the Bronx from the 1930s to the 1960s (Fordham University Press, 2016), “I stumbled upon a large, passionate, and knowledgeable group of people who had been waiting for years to tell stories of communities long forgotten, communities whose very history challenged deeply entrenched stereotypes about Black and Latino settlement of the Bronx.”

For Naison, the project highlights how the borough, defying the odds, rebuilt neighborhoods following the arson of the 1970s and the crack epidemic of the 1980s. The neighborhoods, with lower crime rates, saw community life flourish again, and in recent decades, the Bronx became a location of choice for new immigrants to New York. BAAHP research includes interviews with Bronxites from Ghana, Nigeria, Mali, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Burkina Faso, among other nations. It gives voice to growing, diverse immigrant communities that have enlivened Bronx neighborhoods where Jewish, Irish, Italian, Puerto Rican, and Dominican people lived before them. “The Bronx is this site where people mix their cultures and they create something new,” Naison said. “It makes this a lot of fun to study.”

For Naison, the project highlights how the borough, defying the odds, rebuilt neighborhoods following the arson of the 1970s and the crack epidemic of the 1980s. The neighborhoods, with lower crime rates, saw community life flourish again, and in recent decades, the Bronx became a location of choice for new immigrants to New York. BAAHP research includes interviews with Bronxites from Ghana, Nigeria, Mali, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Burkina Faso, among other nations. It gives voice to growing, diverse immigrant communities that have enlivened Bronx neighborhoods where Jewish, Irish, Italian, Puerto Rican, and Dominican people lived before them. “The Bronx is this site where people mix their cultures and they create something new,” Naison said. “It makes this a lot of fun to study.”

Shaping Global Perceptions

Brian Purnell, Ph.D., FCRH ’00, helped facilitate at least 50 BAAHP interviews from 2004 to 2010, when he was the project’s research director. He said the archive is useful for anyone studying how cities have changed over the decades.

“I hope people use it to think differently about the Bronx, to include the Bronx more deeply and broadly in urban studies in the United States,” said Purnell, now an associate professor of Africana studies and history at Bowdoin College, where he uses the Fordham archive in his own research and in the classroom with his students. “I hope that it also expands how we think about Black people in New York City and in American cities in general from the mid-20th century onward.”

Since 2015, when the BAAHP archives were made available online, the digital recordings have been accessed by thousands of scholars around the world, from Nairobi to Singapore, Paris to Berlin. Peter Schultz Jørgensen, an urbanist and author in Denmark, has been using information from the digital archive to complete a book titled Our Bronx!

“Portraying and documenting everyday life in the Bronx, as it once was, is essential in protecting the people of the Bronx from misrepresentation, while at the same time providing valuable knowledge that can help shape their future,” he said. “Just as BAAHP gathers the web of memory, my book is about the struggles that people and community organizations have waged and are waging in the Bronx. And more important, and encouraging, it talks about how they are now scaling up via the Bronxwide Coalition and their Bronxwide plan for more economic and democratic control of the borough.”

Championing Bronx Renewal

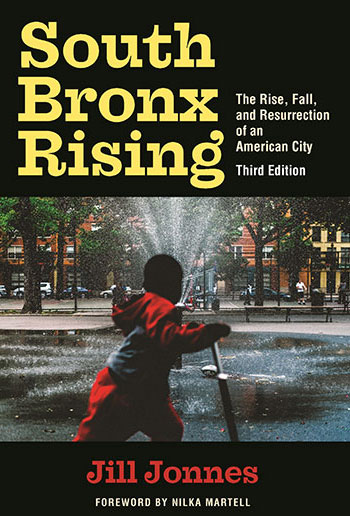

The movement Jørgensen describes is one in which members of the Fordham community have long played key roles, according to historian and journalist Jill Jonnes, author of South Bronx Rising: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of an American City. In the mid-1980s, when she published the first edition of the book, Bronxites were just beginning to reverse the toxic effects of long-term disinvestment and arson that had ravaged the borough.

“Today, we far better understand the interplay of blatantly racist government policies and private business decisions … that played a decisive role in almost destroying these neighborhoods,” Jonnes wrote in a preface to the third edition of South Bronx Rising, published last year by Fordham University Press. “Even as fires relentlessly spread across the borough—as landlords extracted what they could from their properties regardless of the human cost—local activists and the social justice Catholics were mobilizing to challenge and upend a system that rewarded destruction rather than investment.”

“Today, we far better understand the interplay of blatantly racist government policies and private business decisions … that played a decisive role in almost destroying these neighborhoods,” Jonnes wrote in a preface to the third edition of South Bronx Rising, published last year by Fordham University Press. “Even as fires relentlessly spread across the borough—as landlords extracted what they could from their properties regardless of the human cost—local activists and the social justice Catholics were mobilizing to challenge and upend a system that rewarded destruction rather than investment.”

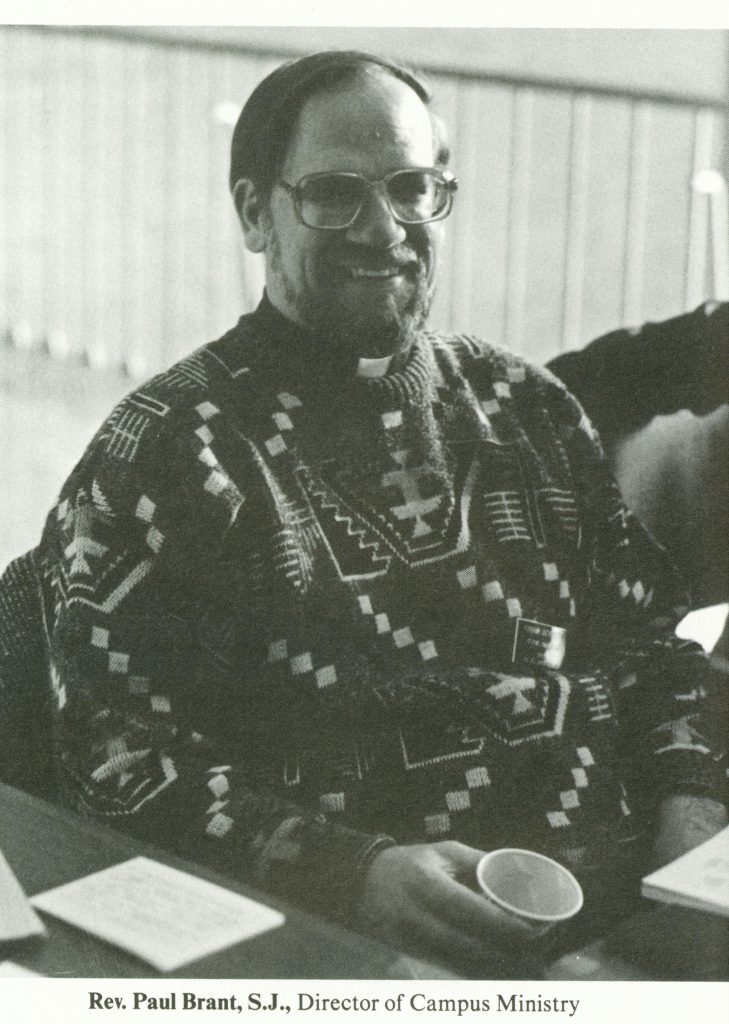

One of those Catholics was Paul Brant, S.J., a Jesuit scholastic (and later priest) who arrived at Fordham’s Rose Hill campus in the late 1960s to teach and to pursue graduate studies in philosophy. At the time, faith in the viability of cities was at a low point. Deindustrialization, suburbanization, and two decades of studied underinvestment had taken their predictable toll. The Bronx was experiencing the worst of it, and the people who lived in its neighborhoods were demonized as the cause of the problems.

Brant, who died in May 2023 at the age of 82, wanted to understand what could be done. He earned a spot in New York City’s prestigious Urban Fellows program, meant to harness ideas for a city in crisis. Gregarious and forceful, yet able to work diplomatically, he had the backing of Fordham’s president at the time, James Finlay, S.J., to serve as the University’s liaison to the Bronx. With other young Jesuits, he lived in an apartment south of campus, on 187th Street and Marion Avenue, gaining firsthand insight into the scope of neglect and abandonment afflicting the borough.

“Paul felt, well, look, there’s a lot of people still in these neighborhoods. It’s not inevitable that everything gets worse,” said Roger Hayes, GSAS ’95, one of Brant’s former Jesuit seminary classmates. “What are we going to do?”

Long conversations with Hayes and Jim Mitchell, another seminary friend, convinced Brant that solutions to the Bronx’s problems would come by directing the power of the people themselves. In 1972, they formed a neighborhood association in nearby Morris Heights. They used relationships within the parish to confront negligent landlords. Seeing nascent successes there, they moved to launch a larger group.

In 1974, Brant convinced pastors from 10 Catholic parishes to sponsor an organization to fight for the community, and the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition (NWBCC) was born. The group expanded to include Protestant and Jewish clergy—membership was always nonsectarian—and went on to train leaders in hundreds of tenant associations and neighborhood groups, including the University Neighborhood Housing Program, which Fordham helped to establish in the early 1980s to create, preserve, and improve affordable housing in the Bronx, and which has been led for many years by Fordham graduate Jim Buckley, FCRH ’76.

All of these groups were knit together across racial lines and around share interests during the worst years of abandonment and destruction. When they learned that rotten apartments had roots beyond individual slumlords, they picketed banks for redlining, the practice of withholding loans to people in neighborhoods considered a poor economic risk. Before long, Bronx homemakers and blue-collar workers were boarding buses to City Hall, demanding meetings with commissioners and testifying at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

With similar people-power organizations nationwide, they won changes in the nation’s banking laws through the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, drove reinvestment to cities, and sprouted a new ecosystem of nonprofit affordable housing.

Preserving Hip-Hop’s Bronx Birthplace

It’s the stuff of legend now: On August 11, 1973, Cindy Campbell threw a “Back to School Jam” in a recreation room at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, a 100-plus-unit apartment building just blocks from the Cross Bronx Expressway in the Morris Heights neighborhood of the Bronx. Her brother, Kool Herc, DJ’d the party, which came to be considered the origin of hip-hop music.

Fast forward to 2008, when 1520 Sedgwick was laden with debt acquired by Wall Street investors who were failing to maintain the building. Organizers from the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board, a group focused on preserving affordable housing, hoped that documenting 1520’s history would help save it. They asked Fordham professor Mark Naison, Ph.D., to help. His research—which led to a lecture on C-SPAN and was highlighted in an August 2008 appearance on the PBS show History Detectives—helped convince the city government to intervene, eventually preserving the building as a decent and affordable place to live. In 2021, its standing became official: The U.S. Congress adopted a resolution acknowledging 1520 Sedgwick as the birthplace of hip-hop.

Learning About Bronx Renewal

Each year, Fordham’s Center for Community Engaged Learning shares this view of Bronx (and Fordham) history with incoming students, particularly those who participate in its Urban Plunge program in late August. The pre-orientation program gives new students the chance to explore the city’s neighborhoods and join local efforts to foster community development.

“For 30 years, the Plunge experience has offered our students their first introduction to institutions like Part of the Solution and the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, organizations founded by Fordham community members in collaboration with local residents that have built community, advocated for justice, and provided services and resources for the whole person,” said Julie Gafney, Ph.D., Fordham’s assistant vice president for strategic mission initiatives and executive director of the Center for Community Engaged Learning.

Students learn directly from local residents and policy experts about how they can shape policy decisions and build a better future for Fordham and its neighbors. “We really want to introduce first-year students, along with their upper-class mentors, to what’s driving community work in the Bronx right now,” Gafney said. “It’s an ideal ground for fostering a four-year commitment to community solution-building here in the Bronx.”

Reimagining the Cross Bronx

On August 25, nearly 250 first-year Fordham students fanned out across the Bronx as part of Urban Plunge. They served lunch to those in need at POTS—Part of the Solution, where Fordham graduate Jack Marth, FCRH ’86, is the director of programs; they helped refurbish Poe Park and the community-maintained Drew Gardens, adjacent to the Bronx River; and they visited the NWBCCC, now led by Fordham graduate Sandra Lobo, FCRH ’97, GSS ’04.

Students also learned about the Cross Bronx Expressway, a major highway built in the mid-20th century that has been blamed not only for separating Bronx communities but also for worsening air and noise pollution in the borough, contributing to residents’ high rates of asthma and other respiratory diseases.

Before visiting parts of the expressway, students heard from Nilka Martell, founding director of Loving the Bronx, a nonprofit that has been leading community efforts to cap the Cross Bronx and develop public green spaces above and around it. A few years ago, Martell connected with Fordham graduate Alex Levine, FCRH ’14, who was pursuing the same goal.

Before visiting parts of the expressway, students heard from Nilka Martell, founding director of Loving the Bronx, a nonprofit that has been leading community efforts to cap the Cross Bronx and develop public green spaces above and around it. A few years ago, Martell connected with Fordham graduate Alex Levine, FCRH ’14, who was pursuing the same goal.

At Fordham, Levine majored in economics and Chinese studies and interned at the Department of City Planning in the Bronx. By 2020, he was a third-year medical student at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, where he co-founded the Bronx One Policy Group, a student advocacy organization focused on capping an approximately 2.5-mile section of the Cross Bronx that runs below street level. The idea is to cover the road with parks and install vents to remove toxic fumes caused by vehicular traffic. They said the cost of the project, estimated to be about $1 billion, would be offset by higher property values and lower health care costs.

“When you think of preventive medicine, it impacts everyone’s life,” Levine told the Bronx Times in 2021. “If we can get a small portion of this capped, then it might be a catalyst to happen on the rest of the highway. This is a project that can save money and lives.”

Martell said Levine’s group connected her with Dr. Peter Muennig, a professor at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health who had published a study on the benefits of capping the Cross Bronx.

“We created this perfect trifecta,” she said. They brought their idea to Rep. Ritchie Torres, and in December 2022, the city received a $2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation to study how to reimagine the Cross Bronx. Fordham’s Center for Community Engaged Learning later received a $25,000 grant from the New York City Department of Transportation as one of only 10 community partners selected to help the department gather input from residents who live near the expressway.

The feasibility-study funding is just a first step, Martell told students during an Urban Plunge panel discussion that featured a representative of the city planning department’s Bronx office and an asthma program manager from the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. “This isn’t easy,” Martell said. “If this was easy and there was a point-by-point playbook on how to get it done, all these projects would happen.”

But recent Bronx history gives her ample reason to press on. “You know, 40 years ago, we had the restoration of the Bronx River. Fifty years ago, we had the creation of hip-hop.” When there was little support and “no other outlet,” she said, “Bronxites came together to create an outlet.”

“For me, this is what it’s like to be a Bronxite; this is what it’s like to be in the Bronx—to have this kind of energy and these organizing skills to get things done.”

—Eileen Markey, FCRH ’98, teaches journalism at Lehman College and is working on a book about the people’s movement that helped rebuild the Bronx in the 1970s and ’80s. Taylor Ha is a senior writer and videographer in the president’s office and the marketing and communications division at Fordham.

]]>Take Frances Berko, for example. A pioneer in the disability rights movement, she earned a Fordham Law degree in 1944. By 1949, Berko, who had ataxic cerebral palsy, helped start United Cerebral Palsy. She later served as New York state’s advocate for the disabled.

“I’ve had much success,” she told a panel of legislators in 1981. “But the one achievement which I held most precious—for which I’ve most constantly striven—I’ve never been able to attain completely: that is, the full rights of a citizen of this country and this state.”

That achievement came in 1990 with the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act. In 1994, two years before Berko died, Fordham awarded her an honorary doctorate, and Janet Reno, then U.S. attorney general, called her “a symbol to me of what you can do and how you can do it magnificently.”

Today at Fordham, Berko’s spirit is evident in the work of senior Abigail Dziura, who has focused her research on improving the New York City subway system, where only 27% of all stations are considered fully accessible to people with disabilities.

In April, she earned a prestigious Harry S. Truman Scholarship, which recognizes college students dedicated to public service. “One of the hardest parts of advocacy work is knowing that you don’t always get to see the end result,” she told Fordham News. “Sometimes you’re setting things up for future generations because something can’t be completed for another 20 years. … But someday, I’d love to see a fully accessible New York subway system.”

The ever-striving, regenerative spirit that links Berko to Dziura and beyond is just one example of Fordham people working to build stronger communities. You’ll find more in our latest “20 in Their 20s” series.

]]>“That richness of thought and perspectives really helps our work,” Jonathan Valenti, FCLC ’98, a principal with Deloitte Consulting, told Fordham College at Lincoln Center students in February.

Last fall, Fordham continued the conversation with students by hosting its first-ever Humanities Day, on September 19. “We all know that today, the humanities are under siege in virtually every university in this country,” Brenna Moore, Ph.D., a professor of theology, said at the event. “The logic seems to be we need a stripped down, efficient society. … Today we gather to push back on this pernicious logic.”

Moore is a member of the Fordham Humanities Consortium, which aims to “help our students flourish as they choose majors that seem increasingly countercultural.” The new group organized the Humanities Day gathering in partnership with Fordham’s Career Center. More than 100 students gathered in the McShane Campus Center at Rose Hill to hear from alumni and faculty about the value of studying philosophy, history, and other humanities fields.

In an article for The Chronicle of Higher Education, Martha C. Nussbaum, a professor in the philosophy department and the law school at the University of Chicago, described one of the less tangible benefits she observed while guest lecturing in a required philosophy course at Utah Valley University.

“What I saw was joy,” she wrote of the spirited debate that followed her lecture. “The sort of joy the philosopher Seneca described: not the flighty joy of the partygoer, but a solid inner joy that comes from discovering yourself.”

For Justin Foley, FCRH ’95, GABELLI ’03, who double majored in urban studies and philosophy, it was about learning to think creatively and being open to new paths, which is how he went from working as a tenant organizer to earning a Fordham M.B.A. to becoming a program organizer for the Service Employees International Union.

“Nobody said, ‘Here’s what your career track is going to be,’” he said. “I really learned to indulge my curiosity about the world around me. … My undergrad time has given me a framework for my values.”

—Franco Giacomarra, FCLC ’19, and Adam Kaufman, FCLC ’08

Why did you study the humanities, and what has the experience done for you personally and professionally? Tell us at [email protected].

]]>Horbatiuk, an attorney who majored in history at Fordham College at Lincoln Center before earning a J.D. at Fordham Law School, has been enthralled by the storied bivalve since reading Mark Kurlansky’s 2006 book The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell. In public talks, he recounts oysters’ emergence as New York City’s leading export in the 19th century, when “New York had street cart vendors selling oysters for a penny a shell.” He also describes the demise of the city’s oyster beds due to overharvesting and pollution.

The Environmental Benefits of Oyster Restoration

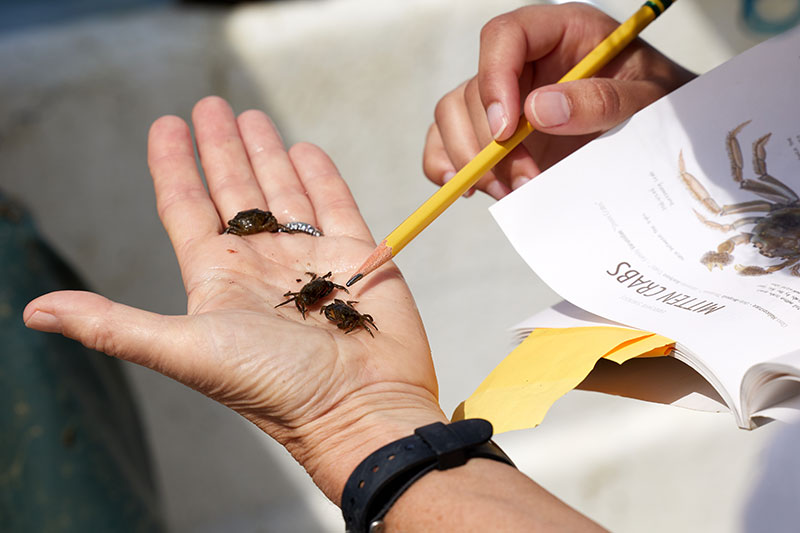

In recent years, New Yorkers like Horbatiuk have been reintroducing oysters, not to be eaten but for the environmental benefits—the mollusk’s circulatory system filters contaminants from the city’s waterways, and the reefs help create habitats for other marine life. On Saturday mornings from May through September, he travels to City Island to measure the oysters’ growth, determine how many of them are growing on each craggy shell pulled from Long Island Sound, and pal around with a diverse group of volunteers devoted to the research project.

Measuring and counting the oysters is painstaking work that demands focus and dedication. Horbatiuk clearly has both, as he works methodically through an orange plastic pail filled with oysters affectionally labeled “Kevin’s Bucket.” His volunteer efforts that sunny Saturday morning in August were part of City Island Oyster Reef’s research study on oyster propagation and biodiversity in Long Island Sound. Among the species found living with the oysters that morning were grass shrimp, bristle worms, skillet fish, slipper snails, and boring sponges.

Horbatiuk recalls that in the 1830s, as many as 39 million bushels of oysters were harvested annually, with New York the center of the world’s oyster trade. Since industrialization, however, the oyster beds died. And today’s oysters, while helping to improve water quality by filtering up to 50 gallons of sea water a day, are inedible because the toxins that get filtered out remain in the oyster flesh.

“The history grabbed me first,” said Horbatiuk, who grew up on New York’s Lower East Side and now lives in the Riverdale section of the Bronx. “Very few people realize how important they are historically and what they do for the water’s health.”

‘Oysters for a Penny a Shell’

Horbatiuk’s love of the city’s past dates back to his undergraduate days at the Lincoln Center campus. His favorite courses focused on social and intellectual history, which helped illuminate developments in pop culture in American society.

His Saturday morning efforts on City Island dovetail with his role as a volunteer as an ambassador for the Billion Oyster Project, which does public outreach on oyster restoration and monitors oyster propagation in New York waterways. That outreach includes talks he gives throughout the metropolitan area to New Yorkers interested in learning more about the history of oysters. At his talks, he’ll mention that the Fanny Farmer cookbook from the 1860s had 40 recipes for oyster dishes. He’ll also hearken back to the early 1600s, when the Lenape people, who had lived in the region for centuries, traded oysters with the Dutch and piled them high in middens along the coast.

“It’s an easy sell to the public,” he says. “It just captures their imagination when you tell them you could find oysters in Spuyten Duyvil in the Bronx, and instead of hot dog carts on the street, New York had street cart vendors selling oysters for a penny a shell.”

In June, he manned a table at the New York Philharmonic performance at Lincoln Center that featured three classical pieces inspired by water—one depicted foreboding ocean moods and a vicious storm, while another portrayed the role of water in an Australian myth. During intermission, he chatted with concertgoers about the oyster project.

In mid-July, he participated in the City of Water Day by visiting the Sebago Canoe Club in Jamaica Bay in Brooklyn to talk about conservation and oyster restoration. That same month he spoke at the Beczak Environmental Education Center in Yonkers about the history of oysters in the Hudson River estuary. That’s where he’s a member of the Yonkers Paddling and Rowing Club and served as club commodore from 2019 to 2021.

“Kevin may be a lawyer, but he’s found another passion: the history of oysters,” said Bob Walters, executive director of the Beczak Center. “He tells that story with such enthusiasm and passion. And he’ll share what he’s learned at the drop of a hat.”

]]>The Emmy and Golden Globe winner is creating a scholarship for Fordham Theatre students, giving back to the university that had a formative influence on her acting career.

At 19, Patricia Clarkson made a decision that changed everything for her. Attending Louisiana State University, near her hometown of New Orleans, she was missing the acting she had done in high school and feeling uncertain about her direction. Then she realized the change she needed: “New York was calling,” she said, “and I just had to go.”

She transferred to Fordham as a junior and flourished. After graduating summa cum laude with a degree in theatre, she earned an M.F.A. from the Yale School of Drama and went on to pursue a variety of complex roles on stage and screen, earning acclaim and awards. These include three Emmys, two of them for her performance in the HBO drama series Six Feet Under, and a 2019 Golden Globe for her work in another HBO series, Sharp Objects. Her other accolades include a 2003 Oscar nomination for her performance in Pieces of April and a best-actress Tony nomination in 2015 for her role in The Elephant Man.

Clarkson has spoken out on many social issues, including LGBTQ+ rights, and in the movie Monica, released last May, she plays an ailing woman being cared for by the transgender daughter she had expelled from her home years before. In the upcoming film Lilly, she portrays equal-pay activist Lilly Ledbetter—whom she recently described to The Hollywood Reporter as “one of my heroes.”

She has regularly returned to Fordham to meet with students in the theatre program. Now, she’s giving them a new form of support—one that reflects her own experience as a student.

Why did creating a scholarship appeal to you?

My heart is always with Fordham. I loved this school. I am always thankful for my beginnings, and I think it’s why I am successful. I know it’s a struggle to be an actor, and I thought, “Well, I’m going to give someone just a little bit of extra help because that’s what I needed when I was there.” With just a little bit more money, it would’ve been easier for me. I’m thrilled and excited to be doing this. I’m proud of my alma mater, and I’m proud to help out in the little way I can.

What was your transition to Fordham like?

I was welcomed with open arms. I had no idea what I was walking into, and I walked into heaven, if you know what I mean, at Fordham. I arrived at this great theatre department and quickly had this extraordinary mentor in [acting professor]Joe Jezewski, and he took me under his wing. He just cared—he said, “You have a gift, Patti, don’t waste it. Let’s really work on it.” He’s the reason I got into the Yale School of Drama. Everyone said, “Oh, you have to have connections to get into Yale,” and Joe was like, “That’s crazy. We’re going to work hard on your auditions. You’re going to get into Yale.” I had this incredible support system, along with my incredible parents who were sacrificing so very much for me to be there. Fordham is conducive to helping people—I think it’s just conducive to learning, and to making you feel at home and making everyone welcome, which is very Jesuit.

Which of your movie roles has had the greatest impact on you?

That would be hard to say because every film you do, every part you play, it still remains with you. I shot Monica almost two and a half years ago, and it’s all still with me.

How does that work?

As actors, we have to like our character and relate to them. Otherwise, you’re just going to be playing [the part], not living it. It has to be a part of you in some way. When I was at Fordham, I started to realize I had a long way to go—acting wasn’t creating, acting was being. And I play, at times, characters that are quite distant from me. In Monica, I’m a woman in probably the last month of life, and I’m quite robbed of speech and movement, often the two biggest assets you can have as an actor. That’s what is exciting about acting—suddenly you’re going to be challenged to find other ways to portray a character. It’s a beautiful film, and I’m proud and thrilled to be a part of it.

With your role in the movie She Said, you helped tell the origin story of the #MeToo movement. Is it having a sustained impact?

Well, it was vital to our industry, a much-needed wake-up call. Women really have risen with the #MeToo movement. Not only are we safer, and not only is our pay better, predatory behavior is no longer accepted. We still have a ways to go, especially behind the camera. And we need more female voices, and we need many more people of color to rise in our business. But we’re making advancements, and that’s what is crucial.

Is there a type of character you haven’t portrayed yet, that you would like to?

Oh God, I played everything, no! I just want a great script and a great director. That’s really all I’m looking for right now.

See related Fordham News article on Patricia Clarkson’s scholarship gift.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Chris Gosier is the director of special projects in Fordham’s marketing and communications division and a frequent contributor to Fordham Magazine.

]]>Disorderly Men: A Novel

In Disorderly Men, Fordham English professor Edward Cahill evokes New York City in the mid-20th century, several years before the 1969 Stonewall uprising catalyzed the movement for LGBTQ+ rights. The novel opens with a police raid on Caesar’s, a mob-owned gay bar in Greenwich Village, where Roger Moorehouse, a Wall Street banker and World War II veteran with a wife and children in Westchester, was about to leave with “the best-looking boy” in the place. “Fragments of his very good life—the fancy new office overlooking lower Broadway, the house in Beechmont Woods, Corrine and the children—all presented themselves to his imagination as fitting sacrifices to the selfish pursuit of pleasure,” Cahill writes.

In Disorderly Men, Fordham English professor Edward Cahill evokes New York City in the mid-20th century, several years before the 1969 Stonewall uprising catalyzed the movement for LGBTQ+ rights. The novel opens with a police raid on Caesar’s, a mob-owned gay bar in Greenwich Village, where Roger Moorehouse, a Wall Street banker and World War II veteran with a wife and children in Westchester, was about to leave with “the best-looking boy” in the place. “Fragments of his very good life—the fancy new office overlooking lower Broadway, the house in Beechmont Woods, Corrine and the children—all presented themselves to his imagination as fitting sacrifices to the selfish pursuit of pleasure,” Cahill writes.

Also caught up in the raid are Columbia University professor Julian Prince and his boyfriend, Gus, a “serious-minded painter” from Wisconsin who gets knocked unconscious by a police baton; and Danny Duffy, a Bronx kid who helps manage the produce department at Sloan’s Supermarket. They’re charged with “disorderly behavior,” and their lives are upended—Roger is threatened by a blackmailer, Danny loses his job and family and seeks revenge, and Julian searches for Gus, who goes missing.

Cahill depicts their crises with pathos, humor, and suspense. And like the best historical fiction, Disorderly Men not only evokes a bygone era but also feels especially vital today.

Midnight Rambles: H. P. Lovecraft in Gotham

The cult writer H. P. Lovecraft was not well known during his lifetime, most of which he spent in his native Providence, Rhode Island. But the so-called weird fiction he wrote in the 1920s and 1930s—a blend of horror, science fiction, and myth—has “entranced readers” and influenced artists in various media ever since, David J. Goodwin writes in Midnight Rambles.

The cult writer H. P. Lovecraft was not well known during his lifetime, most of which he spent in his native Providence, Rhode Island. But the so-called weird fiction he wrote in the 1920s and 1930s—a blend of horror, science fiction, and myth—has “entranced readers” and influenced artists in various media ever since, David J. Goodwin writes in Midnight Rambles.

From shows like Netflix’s Stranger Things to the films of Academy Award-winning director Guillermo del Toro to the novels of Stephen King and beyond, artists have been inspired by Lovecraft’s “vivid world-building and bleak cosmogony.” They’ve also been repulsed by his racist and xenophobic views.

Goodwin, the assistant director of Fordham’s Center on Religion and Culture, deals with this head-on in Midnight Rambles, a chronicle of the writer’s love-hate relationship with New York and the city’s effect on him and his writing. He describes the brief period—from 1924 to 1926—when Lovecraft lived in Brooklyn, drawn there by Sonia Greene, a Ukrainian Jewish émigré he met at a literary convention in Boston. Their marriage soon fell apart, and he moved back to Providence, where he died in 1937 at age 46. “An extended encounter with a great city reveals and exaggerates the strengths, foibles, attributes, and flaws of a character in a film or a person in the flesh-and-blood world,” Goodwin writes. “This is certainly true of Lovecraft and his years in New York City.”

]]>Meet these and 17 other recent Fordham graduates—all in their 20s—who are amplifying the spirit of passionate engagement at the heart of the University’s mission.

]]>A goalkeeper from Ghana pursues his ‘right to dream’

As a child in Ghana, Rashid Nuhu attended Right to Dream, a youth development academy that combines soccer training with academic coursework. He earned a scholarship to the Kent School in Connecticut, where he was encouraged to consider Fordham by fellow Right to Dream graduate Nathaniel Bekoe, GABELLI ’14, who played for the Rams from 2010 to 2013.

Nuhu starred at Rose Hill, helping to lead Fordham to the NCAA Tournament quarterfinals in 2018 before earning a degree in economics.

But professional success didn’t come immediately. He was drafted by the New York Red Bulls in 2019 and spent a year in the club’s development system. Without a contract after parting ways with the organization, Nuhu began training at Rose Hill. One day, men’s soccer coach Carlo Acquista told him about an opportunity to try out for Union Omaha in the third-division USL League One, whose coach had inquired about Nuhu.

“I was like, Yeah, why not?” Nuhu says. “I didn’t have a team. If there’s a team that wants me, that’s what I want.”

Nuhu went to the tryout, made the team, and has thrived ever since, winning a championship with the club in 2021 and earning the 2022 Golden Glove award as the league’s Goalkeeper of the Year.

“It was surreal for me, going through hardship,” he says. “I could have given up, I could have quit, but I kept on going and now things are falling into place, and it feels great to see your hard work pay off.”

]]>An actor finds his footing in film and TV

Miles Gutierrez-Riley says it was at Fordham College at Lincoln Center that he truly grasped how to be a well-rounded actor and person—although the California native has charm and charisma that can’t be taught in the classroom.

Set to appear as Hulkling in the forthcoming Marvel Studios and Disney+ series Agatha: Coven of Chaos, Gutierrez-Riley has already starred in a coming-of-age feature film, The Moon & Back (2022), and the Amazon Studios series The Wilds since graduating from the Fordham Theatre program in 2020.

Amid this year’s historic strikes by the Writers Guild of America and the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, the 25-year-old rising star has been auditioning for theater productions.

“My heart really does lie in theater, and I also love making TV and movies,” he says. “I want the flexibility and the reputation to have a name in all three of those.”

The Collaborative Spirit of Fordham Theatre

Gutierrez-Riley says he chose Fordham Theatre for the individualized attention it offers students and for Fordham’s interdisciplinary core curriculum, including courses in science and theology. He took advantage of the Lincoln Center campus’s proximity to the Broadway theater district. Seeing shows after classes and seeing what he and his classmates could create on a regular basis made the dream feel within reach, he says.

He humbly recalls acting in 10 shows at Fordham, directing one, and being involved in small ways with as many projects as he could. He says his favorite classes, Collaboration I and II, helped him learn to take constructive criticism, creatively engage with others, and garner a deep appreciation for critical communication.

This collaborative spirit lies at the core of the Fordham Theatre program, says Gutierrez-Riley, who credits a former professor, Stephanie DiMaggio, FCLC ’04, with encouraging him to be “a really alive being.”

“She told me things like, ‘When you’re at the deli, talk to the people and say thank you,’ and ‘Take your headphones out on the subway.’ I really didn’t understand this until I was out in the world,” he says. “Having so many different experiences with so many different people is what’s going to make you a strong actor.”

]]>A neuroscientist investigates the drivers of depression

Devin Rocks has always been drawn to the deep mysteries of the brain. When several friends at his high school in Queens, New York, experienced anxiety and depression, his interest in how the brain works—and why things sometimes go awry—only intensified.

“It’s the organ we know the least about, by far,” he says. In his junior year at Fordham, he started conducting research with biology professor Marija Kundakovic, Ph.D., who studies the female brain.

“Many neuroscience studies, even now, are conducted primarily on male animals,” says Rocks, who completed a bachelor’s degree in integrative neuroscience in 2017 and earned a doctorate in biology from Fordham last spring. But women are about twice as susceptible to depression and anxiety than men, and hormonal fluctuations could be part of the reason why, Rocks says.

His doctoral research built on the Kundakovic Lab’s previous finding that when estrogen levels drop in mice, anxiety and depression-related behaviors increase. Rocks, who is now a postdoctoral associate at Weill Cornell Medicine, identified a molecule that seems to be key for mediating changes in gene expression that are linked to the rodents’ behavioral symptoms—a finding that could help pave the way for sex-specific treatments for anxiety and depression, according to Kundakovic, who says that Rocks’ research will be of “great relevance for women’s mental health.”

]]>An investor provides capital for overlooked communities

From the South Side of Chicago to New York City investment banks, Capitol Hill, and Mexico City startups, Israel Muñoz has been all over the map working to change the distribution of capital.

“Even within venture capital, less than two or three percent goes to women, less than two percent goes to people of color,” he says, “and capital is the tool for building the future.”

As a first-generation Mexican American in Chicago, Muñoz became involved in grassroots organizing and activism surrounding public education when he noticed his high school struggling to provide viable resources to students. He earned a scholarship to attend Fordham College at Lincoln Center, where he intended to major in political science but quickly switched to economics—a subject that was “an abstraction” to him until he took an introductory macroeconomics course taught by Michael Buckley, Ph.D.

Attending Fordham at the time of the Occupy Wall Street movement, Muñoz became interested in understanding wealth and income inequality and how economic forces shape the world at large. That curiosity was nourished by his time in the Matteo Ricci seminar, an honors course for students interested in connecting research with community engagement. For Muñoz, the experience deepened his political consciousness and planted the seeds for him to apply for a Fulbright scholarship.

“We spoke about economic inequality and we read Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century. The thoughts about the one percent and power and wealth were really swimming in my head. I think Matteo Ricci just made me a more informed citizen,” says Muñoz, who also earned a Campion fellowship from Fordham’s Office of Prestigious Fellowships that took him to Chile to research education inequality.

Increasingly interested in finance, he interned at UBS, JPMorgan Chase, and in the offices of U.S. Senator Dick Durbin before a Fulbright scholarship took him to Mexico City, where he gained exposure to the Latin American tech ecosystem.

He credits Anna Beskin, Ph.D., then an advisor in Fordham’s Office of Prestigious Fellowships, for her constructive help with his Fulbright essay. “If Anna wasn’t there, I probably wouldn’t have gotten [the opportunity] and become a venture capital investor,” he says.

Since returning from his Fulbright experience Mexico, Muñoz has worked as an investment analyst for the Illinois state treasurer and as an associate at Acrew Capital, a San Francisco-based venture capital fund. He also helped start Angeles Investors, a Hispanic- and Latinx-focused angel investor group.

“I think it’s really important that capital be distributed in a different way,” he says, “so that more of us have a shot at creating the future.”

]]>