The Piedmont, North Carolina

Jade’s lips were burning for a cigarette, her legs jumping underneath the seat as she pulled into the lot of Central High School. She parked and turned to look at Gee. He was slumped against the window, his face pressed against the glass.

She shook him by the shoulder and called his name.

“This is a good thing,” she said. “I wish this had happened to me when I was your age.”

Still, he wouldn’t look at her.

“I’m not saying it’s going to be easy.”

Gee tuned out his mother and surveyed the lot. It was nearly full, although the town hall wasn’t set to start for another half hour. He’d been dreading the start of the school year all summer. He hadn’t had a good night’s sleep since he got the letter approving his transfer to Central. He was gnashing his teeth again.

“You don’t know,” Jade went on, “what a difference this is going to make. This is a good school. I’ve been lucky. I don’t want you to have to count on luck.”

Gee’s mother was good at pep talks, reminding him to doublecheck his homework, put lotion on his hands. She liked to monitor, advise, steer him the right way. Sometimes he thought he ought to be more grateful. But she didn’t seem to notice that his insides were quaking. Gee felt his jaw clamp shut. He pried it open to speak.

“What’s the point of this meeting anyway? What is there to discuss? It’s all final, isn’t it?”

“It’s supposed to be a welcome.”

“Will it be?”

“Sure. One way or another.” Jade gave him a tight smile, then patted his leg and said, “You’ve got to trust me.” They climbed out of the car, and Jade flung her arm around him. It felt strange, but he let her hold him anyway.

The school was four stories, a brick building with white windowpanes and eaves. Dogwood trees guarded the small lawn between the lot and the entrance.

There was a clatter of car doors opening and closing. Gee recognized a few of his classmates and their mothers trudging toward the school. Adira was approaching the school in a fuchsia windbreaker and faded jeans. She had come in regular clothes, and Gee felt conspicuous in his collared pinstriped shirt, his good pants. Adira was calm and easy all the time, even now, sandwiched between her tall parents, the Howards. She was one of the few kids at school Gee could call a friend, but it wasn’t saying much because Adira was friends with everyone. She was the kind of girl who kissed her friends on the cheeks, complimented strangers on their sneakers or hair and meant it. She could reach for you, hug you, wink at you, laugh, and it didn’t seem like flirting. She bounded toward him, snatched up his hand. It felt natural, good. It didn’t set his skin on fire.

The Howards relieved him of Jade, and the adults went ahead, snapping together into a knot, lowering their heads and their voices. Gee couldn’t tell if they were worried. The papers said the initiative to merge the city and county school systems was popular. They were piloting new programs to make all the schools attractive so county kids would want to transfer, too. Most students would get to stay where they were. But it was hard for Gee to believe people were coming to this meeting in droves all because they wanted to shake hands. There had been talk of a band of white parents who planned to protest. He had no particular fear of white people; Gee sorted them into good and bad, safe and not safe, the way he did with everyone else. But he knew even good people could turn, let alone good white people.

Adira had linked her arm with his, and she didn’t seem to be thinking about the meeting at all. She was fawning over Jade. She admired her knee-high boots, her black dress cinched with a silver chain at the waist. “She’s so glamorous,” Adira said. “She doesn’t even look like a mom.”

Jade had recently cut her hair into a mohawk, long on top and buzzed around her ears. Since becoming a nurse, she had stopped wearing her nose ring, but her ears were studded with gold, her nails painted a red so deep it seemed black. She liked to stand out, even now, a day when Gee needed to blend in. Gee shrugged at Adira, and she looked confused, as if he should be flattered, as if he should want people to assume that Jade was his sister and he was a parentless freak.

“What’s the matter? Aren’t you excited? I’ve never even been inside here before. Look at these windows! It’s so bright.”

“My head hurts,” said Gee. It was his go-to line when he had to explain why he wasn’t coming along for a soda after school, or why he hadn’t raised his hand in class, or why he didn’t want to go and meet some girls. Even when it didn’t work, and people saw that it was a lie, he got what he wanted anyway: to be left alone.

They followed the signs down the hallway. The crowd was mostly kids Gee didn’t recognize, shepherded by their fair-headed parents.

They reached the auditorium and saw that nearly every seat was filled, the murmurs of the crowd a low roar. Linette stood sentinel over three seats in the front row, among a contingent of students from Gee’s school and their families. He recited their names to himself like a psalm—Rosie, Ezekiel, Magdalena. Humphrey, Austin, Elizabeth, Yvonne. He’d known most of them since elementary school, and although they were all clumped together now, soon they’d be dispersed, just a handful among the two hundred new students at Central this fall. Would it matter they were all there together? Would they be able to find each other then? Without willing it, his teeth began to grind against each other, back and forth. A sound like tearing paper filled his ears.

Linette could always seem to sense his nerves. She kissed him on the cheek, which did nothing to still his trembling, but he was thankful for her all the same. They settled into the battered, cushioned seats, unlike the hard-backed chairs at Gee’s school. Gee sat between the two women, and they turned their eyes toward the stage.

The blue velvet curtains were swept back, and a dozen school officials sat in a row before a long wooden table. Gee recognized one of them as the principal. She wore a gray suit and pointy heels, her hair pinned into a severe blond bun. Gee had met her at that first meeting in June for the new students who’d be joining in the fall. She had shaken his hand but seemed harried, reluctant. It was a relief that she hadn’t said much, and that he’d had to say nothing, although her silence and her tepid smile had left him wondering whether she was repelled by him.

A black man sat at the edge of the officials’ table, and Gee wondered who he was. He was broad shouldered, clean-shaven, handsome in a blazer and tie. Maybe Gee should have worn a tie, too? He strained to read the little paper sign in front of him that bore the man’s name and title, but he couldn’t see, and soon the principal was calling everyone to order.

She welcomed parents and students, old and new. There was scattered, cheerless applause. Gee made sure not to look at his mother. He could feel the energy of her body. She was burning, desperate to say something out loud. It made him want to disappear.

The principal announced all the good things they had to look forward to: a nearly unchanged student-teacher ratio, class sizes kept under thirty, funding for a whole new line of programming: a choir, a kiln in the art room, a drama club that would put on productions in this very theater. It was what they’d been promised in exchange for the new students. Other high schools had gotten microscopes or specialists to redo the math curriculum; Central had gotten money for the arts. They were gaining more than they were losing, and that was before even accounting for the new students, whose differences would make the community even stronger.

“Now we can say we’re an even better reflection of the city, the county, and the changing face of North Carolina. And above all, the law has spoken. Our representatives have spoken. It’s our duty, as citizens, to open up our doors and move into the future.”

A chorus of boos rolled over the room. The principal held up her hands. “We’re not here for debate. This is a time to look ahead. We’ll open the floor now for questions, words of welcome— that’s why we’re here.”

Before she was through, a line had started to form at each of the microphone stands in the auditorium, one in the rear, the other in the aisle next to Gee, Jade, and Linette. Gee sank lower in his seat. His teeth scraped together, and he felt a familiar shock run from his jaw to his ear. He winced from the pain and listened as the speeches started.

A woman with gray hair and Coke-bottle glasses was first. “I hear everybody here talking about welcome. New beginnings! But what about goodbyes? What about mourning?” She was met with applause, an echo of Yes! “To make room for these two hundred new kids, we’ve had to let go of two hundred kids who have been at Central since they were freshmen. All because the school board and the city have got an agenda? My daughter is losing every single one of her best friends to this new program, and she’s going to be a junior! It’s a critical year, and she’s going to have to start all over! How is that fair?”

By the end, she was shouting, and the cheers went on for so long, the principal had to stand and ask the crowd to quiet down. The deluge kept coming.

“Okay, we’re keeping our teachers; okay, class size is staying the same. That doesn’t mean this school is the same. Everybody knows it’s the students that make the school. And now we’re going to have these kids—these kids who are coming from failing schools—making up twenty-five percent of every grade. Twenty-five percent! They’re going to hold our kids back! These kids aren’t where our kids are in their education or their home training. And it may not be their fault, but it’s not my kid’s fault either!”

A meek-mannered woman with a short black bob and glasses edged to the microphone as if it caused her great pain to do so. She began in a low voice. “Everybody deserves a fair shot in life—I believe that. I always have. That’s what America is about. My son is applying for college this year, and I’ve heard it on good authority that this wasn’t random. That these kids were handpicked because they’re star students. And now, my kid’s ranking is going to fall. What has my son been working for if these new students are going to come in underneath his nose and steal everything he’s been working for, and everything we’ve all been working for? Everything we do is for him.”

“I know this isn’t about integration. It isn’t about what’s right. They put nice words in the pamphlets, but I’m not fooled. This is about money, money, money, and the city being greedy. They’re playing around with my kids’ future. Central might not hit that county quota of no more than forty percent of students on free or reduced lunch. Because we may leave. A lot of us may leave. I’m looking into private school for my girls because I can’t trust the administration here, and I can no longer trust the city I’ve lived in, and that my family has lived in, for generations, for over one hundred years!”

Gee felt Linette stir beside him. Her leg thumped underneath her, and she knotted her hands in her lap. She was nervous, and it was catching. He leaned away from her in his seat. Jade reached over to take Linette’s hand and steady her. The women locked fingers. Jade was swinging her head from side to side, disagreeing with the latest speaker at the podium. Gee knew it was only a matter of time before she burst.

Next there was a man in a plaid shirt, a long beard and sideburns. He pointed at the floor for emphasis with every sentence. He was so steady, so even, it was terrifying.

“Am I the only one who will say it? These kids could be bad kids. What about background checks? How are you going to keep our kids safe? Are we going to put in metal detectors? What about in the hallway, when my daughter is walking between her classes? And what about the parking lot? We ought to put cameras out there.”

Gee felt his vision tunnel, the room around him turn to black at the edges. He mopped his forehead with his sleeve. He was turning inward, closing up. He nearly missed Adira sliding to the microphone, her hands clasped primly in front of her, her head high.

“My name is Adira Howard, and I’ll be a junior here at Central next fall. I came tonight because I was excited. Because I want a future too—”

Gee wondered at Adira. She was stupid and brave and beautiful all at once.

“My family has been here for generations, too. And I deserve my future as much as anybody else. It hurts to know I’m not welcome here, at a school that’s only fifteen minutes away from my house, all because of the color of my skin.”

There was an encouraging whistle from the front row, and the Howards stood up, clapping for their girl. A few white grown-ups stood, too, to applaud Adira, and Gee wondered why they hadn’t spoken yet. Where were all the people who had published op-eds in the paper about the benefits of the program? Where was that majority who supported this change?

When the boos started up again, while Adira was still at the microphone, Jade sprang up to stand in line. A balding man in a crimson polo shirt was set to speak first. He shook his head for a long while before he began.

“This is not about race,” he said. “This is about fairness. We don’t have to give up our rights to the whims of whoever is in office right now. I know it must have taken guts for that little girl to stand up here and speak, but, young lady, you’re dead wrong. This has nothing to do with the color of your skin. I taught at North Carolina A&T, a historically black college, for twenty years before moving here—I am not a racist, and it’s criminal for you, or anyone, to suggest I am.”

There was hooting and screaming for the man at the microphone. The principal hammered at her podium with a gavel she hadn’t used before. The school officials fidgeted onstage, except for the black man who sat calmly on the edge of his seat, his hands folded into a steeple. His eyes were invisible behind the sheen of his glasses. Gee wondered how he managed to sit up there, with all those people watching, whether it was better to be onstage or in the crowd in moments like this. Next, it was Jade.

“My husband wanted the best for our son. We’ve spent our lives trying to figure out how to give it to him. We haven’t had our lives handed to us, like some of the people in this room. For a lot of you, your kids coming to this school is just them inheriting what’s rightfully theirs—the future they’ve been headed toward since they were born. But for my son, it’s a change in his fate. And his fate has been changed more than once, and not for the better, and none of that was his fault.”

Gee felt himself shrink.

“And now that he’s got this chance, we’re not going to let anyone take it from him. He’s not going to be left behind. And I’m going to be here, every morning, and every afternoon, to make sure he’s welcomed the way he ought to be, the way the law says he deserves. Put in your metal detectors. Put your cameras in the parking lot. Let me tell you—you’ll be seeing my face.”

There was whooping and hollering as Jade returned to her seat. Gee felt his anger focus on his mother. She slid into the seat beside him, and he crossed his arms away from her.

“What did I do now?” she asked, and he wondered whether there was a point in being honest.

“I just want to fit in, and you’re talking like you’re ready to go to war.”

“Do you hear these other parents?”

“I don’t care about them. What about me? I don’t want any trouble.”

Jade shook her head. “These people are just talking cause there’s nothing else they can do. You’ll see. You just got to let them know they can’t take you for a punk, that you’ll fight back—”

A shrill voice startled them. Someone at the back of the room was speaking right to Jade.

“To the young woman who just finished up here—”

A fair, slender woman stood at the microphone, her hair large and feathered around her.

“How dare you say anything in my life has been handed to me! If your husband wanted the best for your son, he should have done what I did and moved him into this district fair and square. I made sacrifices to get here. It cost me. It cost my children. And I’m not just going to give it up so you can get handed what you think you deserve—that’s not right, and that’s not American.”

The applause that erupted into the auditorium was the most riotous yet. People stomped and rose in their seats. The principal banged her gavel uselessly. The large-haired woman went on, and Gee couldn’t bring himself to look away from her narrow face, the bright aperture of her eyes.

“There’s a bunch of us,” she said. “We’re putting together a march! And we’re not going to stop there. The school year hasn’t started yet. We’ve got time. I’ll be standing right back here with flyers for anyone else who wants to get involved. Come find me. My name is Lacey May Gibbs.”

From What’s Mine and Yours. Copyright © 2021 by Naima Coster. Reprinted by permission of Grand Central Publishing, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

Naima Coster, GSAS ’12, is the author of the novel Halsey Street (2018), which she began writing as a student at Fordham, where she earned a master’s degree in English with a focus on creative writing. In 2020, she was named to the National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35” list, which recognizes five fiction writers under the age of 35 whose work promises to leave a lasting impression on the literary landscape.

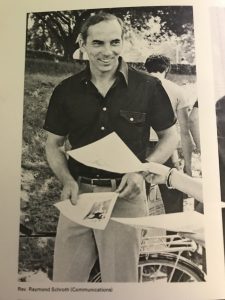

]]>“Ray was consistently demanding but incredibly patient,” Doyle said of Father Schroth, a Jesuit priest, professor, and journalist who died in July 2020 at the age of 86.

A 1955 graduate of Fordham College at Rose Hill, Father Schroth was an associate professor in the communications department at the University from 1969 to 1979 and served for several years during the 1990s as an associate dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill. Throughout his career, he was a mentor to dozens of students who became lifelong friends, including Pulitzer Prize-winning reporters Loretta Tofani, FCRH ’75, and Jim Dwyer, FCRH ’79.

At the memorial service, Doyle shared something Father Schroth wrote about one of his own Fordham professors, someone who had “loomed large as a Catholic intellectual 30 years before.”

“Ray wrote that he knew that ‘inside that handsome gray head and behind that gentle, courtly manner was a flame lit from the first torch ever lit and passed along at Fordham. I knew I should experience it before it flickered out.’”

Countless Fordham students and alumni have beheld that flame through the years and not only kept it from flickering out but taken up the torch and shared their own spark of light with others.

Take, for example, Bill Kiernan, a Long Island brewery owner and AP English teacher. He recently drew on two courses he took with Fordham professor Mark L. Chapman 20 years ago—the Black Prison Experience and the Black Church—to help his own students understand and join national conversations on racial justice following the killing of George Floyd.

Or consider neurochemist Nako Nakatsuka, a 2012 Fordham grad recently named one of MIT Technology Review’s “35 Innovators Under 35.” As an undergraduate, she formed a tight bond with chemistry professor Ipsita Banerjee, collaborating with her on research, motivated by a shared hunger for learning and scientific discovery.

“She was my scientific savior at a time when I was pretty lost and didn’t know how to focus my energy,” Nakatsuka said of Banerjee. “She really put in a lot of time and effort in developing my potential as a scientist.”

The Fordham family is full of such stories. Share yours with us at [email protected].

]]>The album’s first single, “Jeff Goldblum,” is a play on the real-life crush that Brown has had on the actor. In the song, Brown meets a Goldblum look-alike and the song and story evolve from there, with a series of clever lines over some tasty synths reminiscent of the early work of the Cars. It’s fun and hooky and easily should turn more music fans on to the band. And who knows, maybe Jeff Goldblum himself could be one of them?

WFUV Discovery is a new music recommendation from Russ Borris, host of the podcast 8Track and music director at WFUV (90.7 FM, wfuv.org), Fordham’s public media station.

]]>“I would’ve thought, well, I’ve conquered literature, so I might as well take on another art form, perhaps interpretive dance. But Peter kept writing,” he said. “Thank God for dance.”

In September, several months after reissuing Banished Children of Eve, which earned Quinn a 1995 American Book Award, Fordham University Press reissued his follow-up: a noir-tinged trilogy of historical mysteries spanning much of the 20th century, all featuring private detective Fintan Dunne.

“I love Raymond Chandler,” Quinn told this magazine in 2017, but “I always felt that his character Philip Marlowe, he’s really Irish American with his hard-edged blend of cynicism and idealism, and he belongs in New York. So that was the inspiration for Fintan Dunne.”

Set in New York and Berlin during the late 1930s, Hour of the Cat (2005) starts with a homicide investigation—the murder of a nurse, an innocent man on death row—but grows to include the eugenics movement and the lead-up to the systematized murder of World War II.

In The Man Who Never Returned (2010), it’s the mid-1950s, and a retired Dunne is lured by a media mogul into investigating the still-unsolved 1930 disappearance of Judge Joseph Force Crater.

In Dry Bones (2013), Dunne comes face to face with both the Holocaust, through his involvement with an ill-fated Office of Strategic Services rescue mission in Slovakia in 1945, and the moral murk of Cold War espionage on the eve of the Cuban revolution.

Throughout the trilogy, Quinn, who earned a master’s degree in history at Fordham, deftly turns historical themes into suspenseful, literary fiction. As Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist William Kennedy once said, Quinn “takes history by the throat and makes it confess,” invariably aiming his writing at questions that matter.

The Fintan Dunne trilogy is published under New York ReLit, a Fordham University Press imprint publishing reissues of historical, literary fiction about New York or written by authors from New York.

Physicians use sophisticated tools, such as electroencephalograms, or EEGs, to diagnose and monitor brain disorders, but they see only the electrical impulses, which is a bit like hearing two people talking but not understanding what they are saying, says Nako Nakatsuka, Ph.D., a chemist at ETH Zürich in Switzerland. “It’s like a very muffled conversation.”

Scientists have struggled to identify those complex chemical interactions at the time they occur. Often, that requires extracting liquid from the brain and putting it through tedious purification techniques in the lab, a process that can take days.

“I wanted to be able to insert a sensor close to where these interactions happen and monitor this chemical flux in real time,” says Nakatsuka, a 2012 Fordham College at Rose Hill graduate who has spent the past several years developing a chemical biosensor to do just that. The technology she created consists of a glass pipette tapering to just 10 nanometers at its tip, able to get in close proximity to synapses and monitor chemicals at the source. “We’re using nanotechnology to approach the dimensions at which the chemistry happens,” Nakatsuka says.

The invention earned her a spot this year on MIT Technology Review’s list of “35 Innovators Under 35” (out of over 500 nominations). More importantly, it could revolutionize the study of diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s by allowing neuroscientists to truly understand, for the first time, chemical interactions inside the brain as they occur.

Into the World of Bionanotechnology

Nakatsuka spent her formative years attending an all-girls school in Japan, where she was just as interested in art and athletics as she was in science.

“I was able to grow into myself and be confident in the things I liked and pursued without issues such as body image or imposter syndrome,” she says. “No one ever told me, ‘You can’t do that because you are a girl.’” Inspired by hands-on chemistry experiments in high school, she decided to pursue the subject at Fordham, where she also ran competitively on the cross country and track and field team.

An unexpected connection between sports and science led to her interest in nanotechnology. She was taking a course in organic chemistry, and professor Ipsita Banerjee, Ph.D., was her lab instructor. “I was ranting to her about how I had no idea how this stuff was applicable to real life,” remembers Nakatsuka, who at the time had torn a ligament and tendon in her ankle while running, and was on crutches and wearing a walking boot. Banerjee told her about her research in tissue engineering. “She said, ‘Imagine if you could heal yourself by using biocomposites you created in a lab that could mimic the tissue in your body, rather than getting surgery and being out of commission for a year.’”

Nakatsuka was fascinated by the idea. She joined Banerjee’s lab the following fall and plunged into the world of bionanotechnology, a highly interdisciplinary field focused on developing biomolecular composites for biomedical applications in tissue engineering, biosensors, and drug delivery. “She was my scientific savior at a time when I was pretty lost and didn’t know how to focus my energy,” Nakatsuka says. “She really put in a lot of time and effort in developing my potential as a scientist.”

At the time, Fordham lacked much of the equipment necessary for Banerjee’s nanotechnology research, so she would drive her students to Queens College, part of the City University of New York, where a colleague allowed them to use the equipment in his lab. Initially, Banerjee was worried that Nakatsuka’s sports schedule would keep her from the necessary work. Instead, she found her to be an incredibly dedicated researcher. “It didn’t matter if she had exams, or had a meet somewhere, I could rely on her,” Banerjee says. The two developed a tight bond, with the professor sometimes dropping Nakatsuka back at her dorm at 3 a.m. after a night of experiments in the lab and animated conversations about science over breakfast at an all-night diner.

“Since we don’t have a graduate program, I expect graduate-level work from my research students,” Banerjee says. Nakatsuka rose to the challenge, becoming lead author on a review paper on tissue engineering, and co-authoring seven other peer-reviewed papers with Banerjee during her time at Fordham.

Catching the Brain’s Chemical Signals

While presenting one of their papers at an American Chemical Society national meeting in San Diego, Banerjee and Nakatsuka met with Paul Weiss, Ph.D., a UCLA professor and nanotechnology pioneer whose research group combines science, engineering, and medicine. The ability to make a practical difference appealed to Nakatsuka, who joined Weiss’ group as a doctoral candidate after graduating from Fordham.

“It fascinated me to think about using chemistry and biology to do something I was passionate about, and contribute to society,” she says. While there, she began working with aptamers, short single strands of DNA that are specifically designed to attach themselves onto a chemical target.

Nakatsuka was intrigued by the ability these aptamers have to change their shape when latching onto their prey. “It is like when the fingers of a baseball glove come down to capture a ball,” she explains. “They structure switch.”

Nakatsuka began using that property to create a sensor that could detect the presence of a specific chemical in the body. Existing biosensors have struggled to differentiate similar molecules from one another accurately, especially when the desired chemical is in short supply.

“It’s like trying to find and capture one fish in a sea of similar-looking fish that exist in much higher amounts,” Nakatsuka says. Collaborating with nanoscientists and engineers, she created an ingenious probe with a tiny pore at one end that was covered in aptamers designed to capture a specific neurochemical such as serotonin, along with several electrodes. When serotonin was present, the aptamers would switch their structure to make the nanoscale opening more porous, and alter the electrical flow that could be measured by scientists in real time. By calibrating the sensor in advance, they could even tell how much serotonin was present in a given sample.

Toward a Better Understanding of Brain and Body Health

After designing the sensor and earning a Ph.D. at UCLA, Nakatsuka moved to ETH Zürich, a scientific institute with a specialized Laboratory of Biosensors and Bioelectronics, for a postdoctoral fellowship in 2018. She’s now a senior scientist there, working with a team of neuroscientists to train the sensors to detect neurochemicals that could provide new insights into Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, for example, by quantifying neurochemicals in the brain and blood associated with those diseases.

“What’s exciting to me is that there are neuroscience groups that have been focused on one question for a long time—for example, understanding how dopamine is regulated in brain development, or how serotonin is regulated in anxiety and depression,” Nakatsuka says. By distributing her kits to these scientists, she says, she can provide new tools to generate data and answer some of those questions in a much quicker and easier way.

While Nakatsuka’s sensors are currently being used only in the laboratory, she hopes that eventually they could be used in the body, inserted like an acupuncture needle to monitor brain chemistry in patients. They could have applications beyond neuroscience, as well, providing an ability to detect chemicals anywhere in the body—for example, monitoring iron in anemic patients or stress biomarkers for people with anxiety disorders. She envisions people wearing a Band-Aid-like device with the nanopores integrated inside that could withdraw small amounts of blood with a tiny needle to provide ongoing monitoring. “That’s more of an engineering challenge,” she says. “But it’s really not crazy to imagine implementing it in a way that is practical and applicable for daily use.”

From such tiny beginnings, Nakatsuka’s nanosensors have big potential, giving scientists new ways to understand and monitor diseases throughout the body. “Now I often hear, ‘Are you going to commercialize this? When are you going to go on the market?’” she says. “To be honest, I never thought about it, but now it’s something I want to start looking into to see how I might make a larger impact.”

—Michael Blanding is a journalist and the author of three books, including North by Shakespeare: A Rogue Scholar’s Quest for the Truth Behind the Bard’s Work (Hachette, 2021).

]]>All of those attributes are on display in The Tragedy of Macbeth, director Joel Coen’s bewitching, nightmarish film adaptation of Shakespeare’s proto-psychological crime thriller with Washington in the title role.

The film, shot in black and white on stark, expressionistic sets, casts a spell from the start: We hear the rustling wings of three black birds as they ascend and “hover through the fog and filthy air” of medieval Scotland. Washington’s Macbeth, a war hero, emerges from the fog and, emboldened by a witch’s prophecy, colludes with his wife (played by fellow Academy Award winner Frances McDormand) to assassinate King Duncan and claim the throne.

The film, to be released in theaters on Christmas Day and via AppleTV+ in mid-January, had its premiere across the street from Fordham, at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall, during the 59th New York Film Festival in September. At a press conference following the screening, Washington, a 1977 graduate of Fordham College at Lincoln Center, reflected on his Fordham roots.

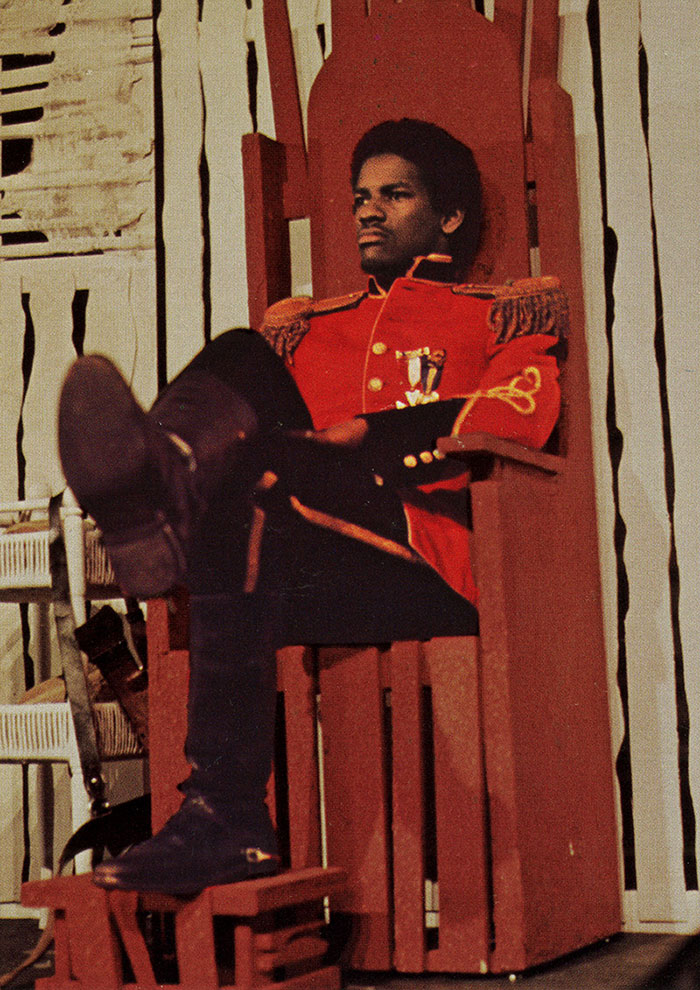

“This is a fascinating journey for me,” he said. “I went to school a thousand feet from here and played Othello at 20.”

It’s a theme that came up again on December 15, when Washington was a guest on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. Right away, the host prompted the actor by sharing a picture of him in his first big role: the title character in a fall 1975 Fordham Theatre production of Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones.

“I was a junior. I thought I was supposed to act mean and be serious,” Washington said.

“Do you have any advice for this kid right here, because he seems pretty confident already?” Colbert asked.

“Ignorance is bliss,” Washington replied, smiling. “That was the first leading role I ever played, and I didn’t know what I was supposed to do. I would go out and peek and look at the audience, you know, count [the people], see if my mom was out there.”

Washington’s mother, who died earlier this year at age 97, was indeed there, he added. “Every night.”

Colbert then listed several of the Shakespeare plays in which Washington has been seen on stage and screen, including a New York Shakespeare Festival production of Coriolanus (1979), the film Much Ado About Nothing (1993), and a Broadway production of Julius Caesar (2005), and asked him how he prepared for his first experience with the Bard.

“After I did The Emperor Jones, I played Othello at Fordham University as well,” Washington said. “At the Lincoln Center library, they had records of the plays, so they had Olivier’s Othello. … I put the headphones on, ‘Oh, my lord,’” he said in a comically high-pitched theatrical voice, to laughter from the audience. “I was like, ‘OK, I’ll sing it like this and make it happen, and people seemed to like it.”

Watch Denzel Washington’s December 15 appearance on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert:

]]>

Those were the words that Good Morning America co-host Michael Strahan said to Matthew Ryba, PCS ’15, in a surprise tribute to him on the ABC program on Veterans Day.

Ryba is a Marine Corps veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan who now serves as the director of community outreach and education for NewYork-Presbyterian’s Military Family Wellness Center.

“You protected lives, you saved lives, and now you’re changing lives,” Strahan continued, before playing a video tribute featuring Ryba’s wife, friends, colleagues, and fellow veterans—as well as a separate message from one of Ryba’s favorite NFL players, Rob Gronkowski.

Ryba’s work centers on helping his fellow veterans with their mental health, especially the lasting effects of PTSD. He recently co-authored a paper titled “Neural changes following equine-assisted therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: A longitudinal multimodal imaging study,” which looked at how time around horses can help veterans with PTSD. It came out of the Man O’ War Project, led by co-directors Prudence Fisher, Ph.D., and Yuval Neria, Ph.D., who is also co-director of the Military Family Wellness Center.

For the project, which took place at the Bergen Equestrian Center in northern New Jersey, Ryba helped recruit 63 veterans who had been diagnosed with PTSD. They were brought to the equestrian center for eight weekly, 90-minute sessions in the summer of 2019, and there, they groomed the horses, led them, and participated in trust-building exercises. Mental health professionals evaluated the trial participants, who also received brain scans before and after the sessions.

Their results, published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, found that half of the patients recovered from their PTSD and continued to show improvement months later. According to an article in NewYork-Presbyterian’s Health Matters, the veterans “reported fewer feelings of depression, distance from others, inability to sleep, anger, and suicidal thoughts,” and “less hypervigilance, nightmares, and feelings of needing to be alert and on guard.” The researchers also found structural and functional changes in the brain.

“Horses almost mirror the emotions of the human that they are with,” Ryba told Health Matters. “So if you walk up to a horse and you’re scared to touch them and show all this fear, they sense that and react with a fear response. Seeing your own fear mirrored in another animal helps you make connections with what’s going on inside you, and make internal adjustments like, ‘If I calm down, the animal will calm down.’”

The team is now piloting a similar study at the center for adolescents with PTSD, as well planning for a larger randomized trial examining the effects of equine therapy on PTSD.

Ryba, who dealt with dozens of his fellow service members dying during his time in the Marine Corps, told Health Matters, “If I’m not helping this population, then I am not doing the right kind of work.”

]]>From stories about his father, who immigrated to the United States from Mexico when Alvarado was 10, to paintings that Alvarado has created to pay homage to farmworkers he knew growing up, Alvarado made clear that raising people out of poverty through education is deeply personal for him.

“Teachers are the ones who are foundational to all disciplines. It is the teacher who taught the Pulitzer Prize-winning author how to write. It is that math teacher that taught that banker basic math facts,” he said in an hour-long conversation with William F. Baker, Ph.D., the Claudio Acquaviva Chair and director of the Bernard L. Schwartz Center for Media, Public Policy and Education at the Graduate School of Education.

“Teachers unlock hope. Hope that students have for themselves, and hope that families have for their children. It drew me because it’s a profession that’s grounded in hope.”

Alvarado joined Fordham in July, after serving as provost and vice president for academic affairs at Cal State Los Angeles, the founding dean of the College of Education at California State University Monterey Bay, and associate dean of the College of Education at San Diego State University.

The conversation, which was organized by Fordham’s office of alumni relations, was a mix of questions from Baker as well as those submitted by attendees. In addition to sharing the reasons he got into education, Alvarado and Baker discussed current topics such as the recent politicization of the field of education.

Alvarado agreed it had become a problem, noting that just last month, the governor of Florida barred professors at the University of Florida from testifying about voting rights in a court case. Membership in the Flat Earth Society, he noted, is also on the rise.

“It’s a world that’s topsy turvy, and teachers I think, have to be the steady hand in all of that. Science, facts—teachers have to uphold those,” he said.

Alvarado was asked what it was like to embrace a private university after a career in public education. He noted that in addition to being impressed with Fordham’s dedication to cura personalis—care for the whole person, he also found it encouraging that GSE students, on average, find gainful employment sooner after graduation.

Asked how GSE is supporting Catholic education in New York City, Alvarado said that just a day earlier, they had held a recruitment event at a Catholic high school in the Bronx for teachers who have not yet earned their state teaching certification Catholic school teachers, he noted, receive a tuition discount at GSE.

When it comes to his priorities, Alvarado said he wants to make it easier for students of modest means to follow his own path, from high school to teaching certification. One of those plans involves establishing agreements that provide a way for students in community college (which Alvarado attended) to earn a bachelor’s and master’s degree and a teaching certificate in five years. He also encouraged alumni to reach out to help mentor first-generation students.

During the discussion of Alvarado’s art, attendees saw that some of his pieces reflect the beauty of the world, while others are meant to highlight the powerful and quiet dignity of the working person.

In Strawberry Pickers, a 36- by 42-inch canvas painting, he explained that he split the painting into six panels to show how field laborers sometimes live fractured lives.

“They may be seen as part of an expendable workforce in the fields, but they may be esteemed members of their community, where they’re respected in their church and they’re respected in their families,” he said.

Alvarado became emotional while recounting the experience of working as a landscaper’s assistant in high school. When he told his grandmother how he was embarrassed to picking up dog poop on the lawns of his rich classmates “who were frolicking in their pools,” she told him,

“To steal brings shame. There is no shame in hard work.”

“Much of the work I do tries to show the dignity of the work, and the potential. I think of my father. He only went to the school until the third grade in Mexico. He was a brilliant man. He never had opportunities. So, for me, every kid that I see in an inner-city school, I see a future doctor, a future teacher, a future banker,” he said.

“It’s about creating opportunities and acknowledging that even if someone doesn’t have two or three letters after their name, it doesn’t mean they’re any less of a human being. They have tremendous potential and worth, like anyone else.”

To watch a recording of the town hall, visit here.

]]>

“I found all these histories that I had never read in high school,” Kiernan said of the classes, which were taught by Mark L. Chapman, Ph.D., associate professor and associate chair of Fordham’s Department of African and African American Studies.

Kiernan reached out to Chapman and invited him, along with two other Fordham professors, Mark Naison, Ph.D., and Claude Mangum, Ph.D., to visit the Long Island brewery he co-owns. The group got together at Sand City Brewing Co. last June.

“I hadn’t seen these professors in [almost] 20 years,” Kiernan said. “It was such a positive reunion. That whole notion of caring about the individual, caring about society, trying to promote justice in a pragmatic way, those were things that the professors really inspired in me.”

In a Facebook post, Naison said visiting the brewery and hearing about Kiernan’s work as a teacher made him proud of Fordham.

“Spending time with [this] remarkable grad … gave me a deep appreciation of my faculty colleagues and everyone else on campus who inspired [his] commitment to making the world a better place,” Naison wrote.

Dual Career Paths, Both Cultivated at Fordham

After graduating from Fordham College at Rose Hill in 2002 with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy and religious studies, Kiernan worked in the contracts department at Random House. He often talked about books the company was publishing with one his former teachers, the chair of the English department at his high school alma mater, St. Anthony’s in South Huntington, New York. When a half-year teaching job opened up at the school in 2005, the chair encouraged Kiernan to apply. He got the job, went on to earn a master’s degree in education from Molloy College and a master’s in educational leadership from Long Island University, and now he’s an Advanced Placement literature and composition teacher at St. Anthony’s.

Meanwhile, in the early 2010s, a friend named Kevin Sihler approached Kiernan with the idea of opening up a brewery in Northport. After several years of planning, they opened Sand City in 2015, and this year, they launched a location in Lindenhurst, on Long Island’s South Shore, with Kiernan focusing on the day-to-day business operations of the company.

While committing to two careers can require long hours, Kiernan said that his love for teaching made it an easy decision for him to keep working at St. Anthony’s as the brewery grew. He also said that his Fordham education, aside from influencing his teaching, has had a big impact on his approach as a business owner.

“The Fordham education really significantly impacted me in a couple of different dimensions, one being the spiritual, [inspiring a] concern for the dignity of the individual,” he said. “As a teacher, that goes without saying. But as an employer, when I think about my employees and their health and well-being and the goal of developing them as individuals, I think so much of that goes back to the way we were cultivated at Fordham.”

He also said that the critical thinking skills he developed as a philosophy major have helped him run the brewery.

“The types of conversations you have, the types of logic problems you solve, all these things prepared me unknowingly to confront problems in the world and try and figure out solutions to them in my business,” Kiernan said.

That combination of a pragmatic liberal arts education and the spiritual and political value of classes like the ones he took with Chapman had such a positive impact on Kiernan that when his high school students are looking at colleges, he heartily encourages them to apply to his alma mater. He also said that living in a vibrant Bronx community as an undergraduate provided him with an “unspoken curriculum of how to actually function in society.”

“When I hear students want to go to Fordham, I’m like, ‘There’s no question in my mind that you should.’”

]]>Because, we’d say, he was a fulcrum in the lives of those who formed themselves around him. Because he paid us the compliment of driving us hard as students and then, in the decades to come, sustaining us individually and collectively with the shared bread of his friendship—like one of the righteous souls that the Talmud is always mysteriously crediting with holding this world together.

At least that’s how it seemed to those who knew him.

So we gathered on a cloudy day during the lingering pandemic in a stone church with its vault of azure blue. We warbled out upbeat songs, singing of alabaster cities gleaming, undimmed by human tears; of a tender Lord who extracts us when we’re snared like a bird in a fowler’s trap; and of the biggest promise ever made: resurrection after death.

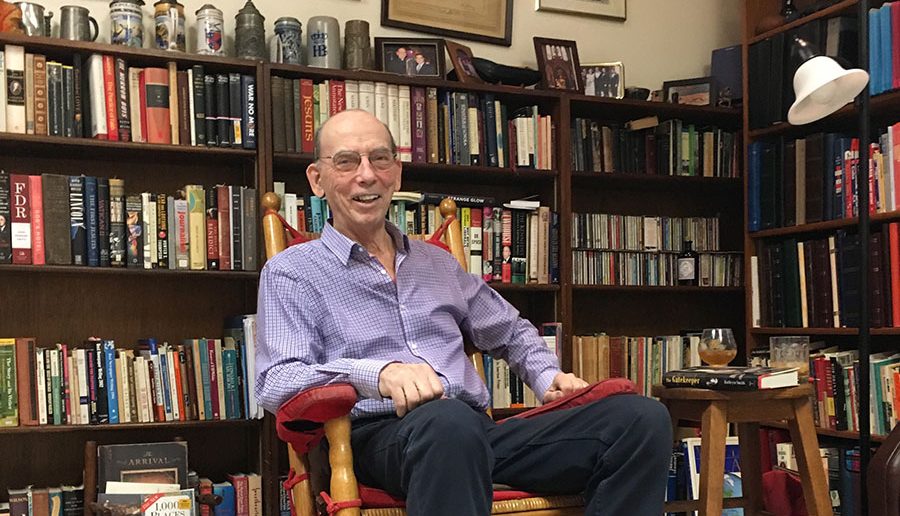

Most of us had begun as Ray’s students at one Jesuit university or another, Fordham included. He was blatantly magnetic, a man-about-campus with a playful smile and form-fitting Izod shirt. But his main devotions were interior: to intellectual pursuits and his vocation as a priest. He celebrated Mass with a marked sincerity and taught his classes with a passion. He published his writing—rigorous journalism with a disarming dash of memoir—in national publications. And in his music-filled apartment, next to the armchair, was an elbow-high stack of magazines and books. He would read them all, sometimes late into the night after a steak-and-martini dinner with friends at an Arthur Avenue restaurant, rebuilding the stack as he went.

Somehow, Ray made his life of the mind seem glamorous—like if you yourself couldn’t get in on it, you’d keel over from an acute lack of fulfillment. Then one day he’d tap you on the shoulder, so to speak, and allow that he saw something in you. This was both thrilling and nerve-racking for the way it made you want to measure up. It embarked you on what felt like an adventure of spiritual striving and cold ocean swimming, high literary endeavor and incessant bonhomie. The bonus was membership in a community not of his followers but his brethren.

Years later, at the memorial at Fordham, a few of us sang his praises. “Ray was not a Catholic apologist but he was also not an apologetic Catholic,” said Kevin Doyle, FCRH ’78, a lawyer who has applied himself to defending men on death row. “He ached to be generative,” added Anne Gearity, TMC ’70, GSS ’74, about Ray’s zeal for teaching. She herself is a therapist who teaches children to cope with trauma.

Author Eileen Markey, FCRH ’98, noted the absence of Ray’s prize student, Jim Dwyer, FCRH ’79, who’d been one of his closest friends. A Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist of impeccably chiseled prose, Jim had been lined up long ago to deliver the eulogy. But before a memorial could be held, he died of cancer, a loss so devastating that it bordered on the absurd. All the more reason, Eileen observed, to gather at liturgy and find shelter with each other.

Afterward at a reception, there were mini muffins and comforting conversation, which is how I imagine the anteroom of heaven. Still, life haunts you. I kept dwelling on what Kevin Schroth, a professor at the Rutgers School of Public Health, had said at the Mass about the last two years of his uncle’s life: “Ray told me he was at peace with his condition, that he understood why he had to go through it.”

On a summer day in 2018, Ray was taking a walk on Webster Avenue when a stroke knocked him to the pavement. Remember those righteous men and women of the Talmud? This is how they quietly move among us, keeping chaos at bay through the practice of some discipline, until the chaos comes for them. Ray lost his ability to walk and write and gained a problem with swallowing that put him on a feeding tube. He entered a season of suffering. And yet, he clung to delight. He’d still beam at the sight of friends at his door, lifting his head as if lit from within. As if no loss in the world could keep him from loving you.

—Jim O’Grady, FCRH ’82, recently joined NPR’s Planet Money as a host and reporter after more than a decade at WNYC, where he earned numerous honors, including two Edward R. Murrow Awards. He is also the host of the podcast Blindspot: The Road to 9/11, a co-production of HISTORY and WNYC Studios.

Scenes from the memorial Mass and reception held at Fordham on October 23, 2021. Photos by Bruce Gilbert

[doptg id=”173″] ]]>

The 2021 Fordham Founder’s dinner was marked by firsts: the first time the dinner raised more than $3 million; the first time in more than two years that the event has been held in person; Fordham’s first time at The Glasshouse, a sparkling new venue on the West Side of Manhattan; and the official launch of the University’s new fundraising campaign, Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student.

The 2021 Fordham Founder’s dinner was marked by firsts: the first time the dinner raised more than $3 million; the first time in more than two years that the event has been held in person; Fordham’s first time at The Glasshouse, a sparkling new venue on the West Side of Manhattan; and the official launch of the University’s new fundraising campaign, Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student.

Fordham’s donors, alumni, and friends gathered on Nov. 8 not only to honor the Founder’s Scholars—Fordham students whose scholarships are supported by the event—but also to pay tribute to the evening’s honorees: Emanuel “Manny” Chirico, GABELLI ’79, PAR; his wife Joanne M. Chirico, PAR; and Joseph H. Moglia, FCRH ’71.

“I would like to thank all of you for supporting this long-overdue annual celebration of our beloved University,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham.

Father McShane noted that there was “eager longing” for this Founder’s Dinner, in part because of the last 18 months but also because it kicked off the new campaign for the student experience.

“We also celebrate the public launch of the Cura Personalis campaign, a campaign that will make it possible for the University to continue to redeem the promise that it has made to its students for 180 years: the promise to provide them with the kind of personal, empowering, and transformative care that has always been the hallmark of a Fordham education,” he said. “I am happy to tell you that, thanks to the generosity that you have already shown, we have already raised $170 million toward the $350 million goal. And for that, I thank you from the bottom of my heart.”

All attendees were required to be fully vaccinated and wear a mask when entering The Glasshouse, which featured sweeping views overlooking the Hudson, outdoor terraces, and an airy ballroom lit by modern chandeliers.

Supporting the Students

David Ushery, the anchor for NBC 4 New York’s 4 p.m. and 11 p.m. weekday newscasts, emceed the Founder’s Dinner, which began in 2002 and has raised more than $42 million to support the Fordham Founder’s Scholarship Fund. Ushery received an honorary doctorate from Fordham in 2019, and his wife, Isabel Rivera-Ushery, is a 1990 graduate of Fordham College at Rose Hill.

“You have supported 130 Fordham students through this program—students who would not have benefited from our fine Jesuit education without your support and generosity,” Ushery told the more than 1,000 attendees. “You have impacted the scholars’ career paths as they are ‘setting the world on fire.’ Your impact on them guides their impact on others.”

The New Campaign

That impact will be taken to new levels through the University’s new fundraising campaign. Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, which aims to enhance the student experience as well as prepare students to work for social justice and be leaders in today’s world. The campaign pledges to renew Fordham’s commitment to care for the whole student as a unique, complex person and to nurture their gifts accordingly.

The campaign features four main pillars: access and affordability, academic excellence, student wellness and success, and athletics—with diversity, equity, and inclusion goals embedded in each of them. The night also featured the debut of a new campaign video that highlights the student experience at Fordham.

Founder’s Scholar Sydney Veazie, a senior at Fordham College at Rose Hill, said that the Jesuit value of cura personalis, or care of the whole person, has been an essential part of her experience at Fordham. At Fordham, Veazie said, the Latin noun cura is transformed into a verb—something that students, faculty, and staff put into action.

“[Cura Personalis] becomes an active call, a mission statement, and a defining feature of this University to care for the students who call it home—to attend to us and to our needs,” said Veazie, a double major in international political economy and classical civilization. “Each student can expect personalized care, personalized attention during our time here.”

Veazie, a Fordham tour guide who currently volunteers as a team lead for the Fordham chapter of Consult Your Community and at Belmont High School, said she plans to take the lessons of cura personalis that she learned at Fordham and carry them forward.

“I’ll be going to law school in the fall of 2022, and I eventually hope to work in government and politics and infuse cura into everything I do,” she said.

Veazie said that none of this would have been possible for her or her fellow Founder’s Scholars without the support of those in attendance.

“I cannot stress enough how important this kind of investment is,” she said. “Fordham’s emphasis on cura personalis yields a student body, a community, that itches to pay forward the lessons, the care, and the holistic development we’ve received during our time here.”

Thomas Reuter, a senior at Fordham College at Rose Hill and United Student Government president, served as student MC for the second half of the program. He said the campaign will help ensure that all students feel at home at Fordham and that they’re able to take advantage of the opportunities the University offers.

“This campaign will invest in what we love most about Fordham…its student-centered Jesuit, Catholic education that nurtures the whole person,” he said. “This campaign will renew and enhance our distinctive educational experience that has transformed lives since Fordham was founded in 1841.”

Honorees

Father McShane expressed gratitude to the evening’s honorees for their efforts to support Fordham’s mission and its students.

“You are extraordinary … you are generous with your time, treasure, and talent … and you stand as exemplars of the renewal of the University in its identity and mission,” he said.

Manny Chirico, a titan of the fashion industry, is the longtime chairman and CEO of PVH Corp., the world’s second-largest apparel company; he plans to retire next month. Chirico served as the company’s CEO beginning in 2006 and as its board chairman since 2007. He currently serves on the boards of Montefiore Medical Center and Save the Children, while Joanne serves as the vice president of the Parish Council at Immaculate Conception Church in Tuckahoe, New York, and is on the board of Montfort Academy.

Manny, who is also a Fordham trustee, recalled that when he was a senior at Fordham, he took a philosophy class with a Jesuit professor who quoted St. Ignatius Loyola: “Go forth and set the world on fire.”

“I really like that quote, it sounded like something Vince Lombardi would say just before he sent his team out to play in the Super Bowl,” Chirico said. “I had no idea what it meant, but I wrote it down in my notebook.”

Chirico said that he asked the priest what this quote actually meant.

“In typical Jesuit fashion, he said to me, ‘Young man, that’s what you need to figure out,’” he said. “So for the last 40 years, I’ve been trying to figure out what it means to go forth and set the world on fire—I’m still working on it—but I do realize that there is no formula and no set answer. It’s a challenge to make a difference in the small things we do every day.”

Joe Moglia has combined his love of finance and football throughout his life, working as a championship-winning defensive coordinator at Dartmouth before joining the MBA training program at Merrill Lynch and eventually becoming CEO and chairman of TD Ameritrade, a post he held for more than 24 years, before returning to football as the head coach at Coastal Carolina University. Moglia currently serves as the chair of athletics at Coastal Carolina and board chairman of Fundamental Global Investors and Capital Wealth Advisors.

When he was a senior at Fordham, Moglia took a job coaching at Archmere Academy in Claymont, Delaware, and said that he wanted to provide his players with something more than just a desire to win.

“How do you lay the foundation upon which those boys become men?” he said.

“We created a philosophy that said, ‘A real man, a real woman, a real leader, stands on their own two feet, takes responsibility for themselves, always treats others with dignity and respect, and deals with the consequences of their actions,” he said.

Moglia said that this mindset and philosophy came from Fordham.

“This is a university for others, that loves others, so for me, for whatever I may have accomplished in my life, at the end of the day I’m so incredibly proud to be part of Fordham … and hopefully as I go forward, I continue to make Fordham proud,” he said.

The Chiricos and Moglia were originally supposed to be honored in 2020, but that Founder’s Dinner was canceled due to the pandemic. They were also recognized earlier this year at a virtual toast for scholars and honorees.

The night also featured several performances: Tyler Tagliaferro, a 2017 graduate of the Fordham College at Lincoln Center, played the bagpipes as guests walked in; the Young People’s Chorus of New York City performed; Jesira Rodriguez, a Fordham College at Lincoln Center senior and a Founder’s Scholar, sang the national anthem; and the Fordham Ramblers closed the evening with an a cappella rendition of “The Ram,” Fordham’s fight song.

Father McShane called on those in attendance to honor the members of the Fordham community who preceded them by investing in and supporting current students.

“You were formed by and now possess the intangibles that make for Fordham’s greatness, and that distinguish Fordham from other universities,” he said. “You are men and women for others. You are men and women of character, grit, determination, integrity, expansiveness of heart, and restlessness of spirit. And so, I turn to you to enable Fordham to make the kind of rich transformative experience that you received here available to your younger brothers and sisters.”