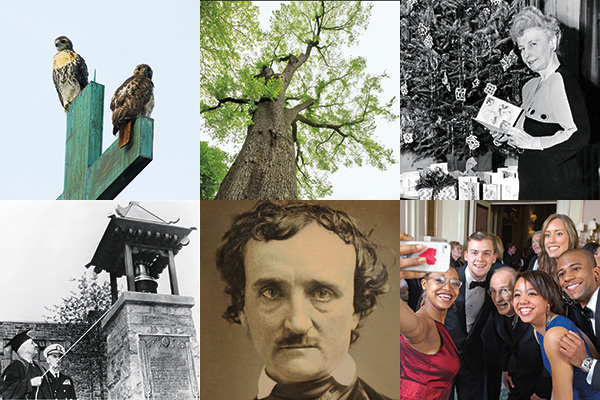

This year, as we mark our 175th anniversary, we celebrate our Catholic, Jesuit roots; our abiding ties to New York City; and the hundreds of thousands of men and women whose lives Fordham has touched and changed since 1841.

Here are 175 stories, a mere sampling of the people, places, objects, gifts, discoveries, ideals, and events that have shaped—and been shaped by—the Jesuit University of New York.

Taken together, they provide a sense of Fordham’s history and influence. They link generations past and present. And they point us toward the stories of wisdom, learning, service, and faith that will continue to define us in the years and decades to come.

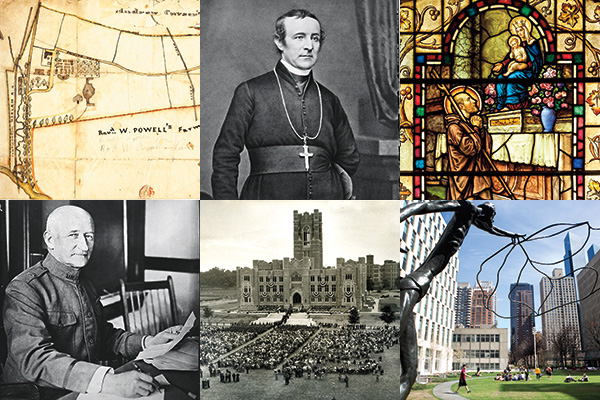

On June 24, 1841, John Hughes, the 44-year-old coadjutor bishop of New York, welcomed the first six students to St. John’s College in the village of Fordham. It was the first Catholic institution of higher education in the Northeast—“a daring and dangerous undertaking,” he later admitted, not least because he initially lacked the $29,750 to purchase the 106-acre estate where he saw a great university taking root.

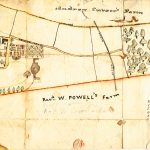

2. We Were on the Map in 1841

The earliest known map of Rose Hill, circa 1841, shows the main building of the college and the names of the neighboring farms.

The earliest known map of Rose Hill, circa 1841, shows the main building of the college and the names of the neighboring farms.

3. We Became a Jesuit Institution in 1846

The Society of Jesus, founded in 1540 by St. Ignatius Loyola, purchased the college for $40,000 in November 1845. The Jesuits arrived the following spring, fulfilling the ardent hopes of Bishop Hughes, who had long sought to place the school in Jesuit hands.

The Society of Jesus, founded in 1540 by St. Ignatius Loyola, purchased the college for $40,000 in November 1845. The Jesuits arrived the following spring, fulfilling the ardent hopes of Bishop Hughes, who had long sought to place the school in Jesuit hands.

4. Our Founder Championed Immigrants

Before he established Fordham, before he was archbishop of New York and the most famous Catholic in America, John Hughes was a minimally educated 20-year-old Irish immigrant who lived off menial work like digging ditches.

Before he established Fordham, before he was archbishop of New York and the most famous Catholic in America, John Hughes was a minimally educated 20-year-old Irish immigrant who lived off menial work like digging ditches.

“He just really had no prospects,” said John Loughery, FCRH ’75, author of a forthcoming book on Hughes.

What he did have, however, was a pugnacious spirit and devout faith that fueled his extraordinary efforts to help Irish, Catholic immigrants overcome virulent prejudice and thrive in the United States.

Hughes earned only a grammar school education in Ireland, and after arriving in America in 1817 worked as a laborer and gardener before entering Mount St. Mary’s seminary in Maryland.

Ordained in 1826, he gained prominence in Philadelphia by effectively debating the Rev. John A. Breckinridge—a Protestant clergyman—about the legitimacy of their respective faiths. He became known as a strong defender of the church, a reputation that would only grow as he was named New York’s coadjutor bishop in 1837, its bishop in 1842, and its archbishop in 1850.

He faced a steep challenge: Destitute Catholic immigrants were arriving in the city at a rate that would increase dramatically during the late 1840s, as tens of thousands fled the devastating potato famine in Ireland. They were falling into crime, living in filthy conditions, and doing without education because Catholics were unwelcome in the Protestant-leaning public schools. Determined to keep them from slipping into second-class status, Hughes set about raising funds and planning for institutions that would help elevate his immigrant flock.

In addition to founding Fordham as St. John’s College in 1841, Hughes played a major role in establishing the Catholic school system in the archdiocese. More than 100 schools had been created by the time of his death in 1864. He also worked to create the Emigrant Aid Society to help immigrants find jobs or get on their feet, and energetically raised funds for Catholic orphanages. He set in motion the construction of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. And he took tough stances, like staving off a nativist attack on Catholic churches by telling New York’s mayor he would respond by turning the city into a “second Moscow,” referring to that city’s destruction during Napoleon’s invasion.

Through the incredible scope of his efforts, Hughes would come to be regarded as the man who saved the Irish in America. And for all his rhetorical duels with Protestants, he espoused ideas of religious toleration that were ahead of their time. He once wrote that “every denomination, Jews, Christians, Catholics, Protestants—of every shade and sex—[are]all entitled to entire freedom of conscience … no matter how small their number or how unpopular the doctrine that they profess.” The church would echo these ideas in 1965 through the Second Vatican Council’s Declaration on Religious Liberty.

“At least in this all-important area of freedom of conscience,” said Msgr. Thomas Shelley, GSAS ’66, professor emeritus of theology at Fordham, “our founding father anticipated the work of the Second Vatican Council by a whole century.”

5. The First Graduating Class Had Six Students

An entry from the diary of Thomas Legoüais, S.J., a professor, lists the names of Fordham’s first graduates. The commencement ceremony was held on July 15, 1846. Six students received A.B. degrees, and one professor received an honorary master’s degree.

An entry from the diary of Thomas Legoüais, S.J., a professor, lists the names of Fordham’s first graduates. The commencement ceremony was held on July 15, 1846. Six students received A.B. degrees, and one professor received an honorary master’s degree.

6. The Law School’s Founding Dean Was Once a Homeless Orphan

Established on September 28, 1905, the School of Law thrived under the leadership of its first dean, Paul Fuller—particularly after moving from Rose Hill to Manhattan the following spring. Fuller had been orphaned and was homeless by age 9, but he rose to become one of the leading international lawyers of his generation, a partner at the Courdert Brothers firm. In Fuller, students found the first great model of a Fordham lawyer: humble, driven, high-minded, and committed to professional success and public service.

Established on September 28, 1905, the School of Law thrived under the leadership of its first dean, Paul Fuller—particularly after moving from Rose Hill to Manhattan the following spring. Fuller had been orphaned and was homeless by age 9, but he rose to become one of the leading international lawyers of his generation, a partner at the Courdert Brothers firm. In Fuller, students found the first great model of a Fordham lawyer: humble, driven, high-minded, and committed to professional success and public service.

7. The Woolworth Building Was Our Home

On November 6, 1916, the Woolworth Building—then the tallest building in the world—became Fordham’s “marble campus” in Manhattan, where the University established its graduate schools of arts and sciences, education, and social service. The three new schools were coeducational from the start. They joined Fordham Law, which had moved into the building in 1915.

On November 6, 1916, the Woolworth Building—then the tallest building in the world—became Fordham’s “marble campus” in Manhattan, where the University established its graduate schools of arts and sciences, education, and social service. The three new schools were coeducational from the start. They joined Fordham Law, which had moved into the building in 1915.

8 to 10. Three of Our Graduate Schools Turned 100 This Year

Fordham’s Dodransbicentennial coincides with the 100th anniversary of the founding of three schools:

8. The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

In its early years, the school offered courses in scholastic philosophy, literature, history, economics, and other subjects. It added a science department in 1919, and 16 years later, moved into the newly completed Keating Hall on the Rose Hill campus.

9. The Graduate School of Social Service

From the start, the school offered a two-year academic program that included both classroom lectures and supervised fieldwork.

10. The Graduate School of Education

Originally called Teachers’ College, the Graduate School of Education was started to meet the demand for well-trained teachers and administrators in parochial and public schools throughout the city.

11. The Gabelli School Started as a CPA Training Course

In September 1920, on the seventh floor of the Woolworth Building, Fordham began offering a course to prepare candidates for the Certified Public Accountant Examination. By 1926, the business school offered a bachelor’s degree program, including courses in accounting, economics, and commercial law.

Today, the Gabelli School of Business—named in honor of Fordham benefactor Mario Gabelli, the chairman and CEO of GAMCO Investors Inc.—comprises undergraduate, graduate, and executive-level programs. This fall, the school launched a five-year, research-intensive doctoral program, thanks to generous support from Gabelli, a 1965 Fordham graduate.

12. We Were the First to Build at Lincoln Center

In 1958, New York City Mayor Robert Wagner signed the deeds transferring approximately eight acres of Manhattan real estate to Fordham as part of the city’s Lincoln Square Urban Renewal Project. Laurence J. McGinley, S.J., then president of the University, wrote: “February 28, 1958, will probably prove to be the most significant date in Fordham University’s modern history.”

In 1958, New York City Mayor Robert Wagner signed the deeds transferring approximately eight acres of Manhattan real estate to Fordham as part of the city’s Lincoln Square Urban Renewal Project. Laurence J. McGinley, S.J., then president of the University, wrote: “February 28, 1958, will probably prove to be the most significant date in Fordham University’s modern history.”

Three years earlier, Robert Moses, the powerful New York City planning official, had invited Fordham to be part of the project that would also create Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts and include the Juilliard School. Fordham was the first of the city’s institutions to fully sign on to the project and move to the area. The first building, Fordham Law School, opened in 1961, with the Lowenstein Center to follow seven years later.

13. Our Theater Roots Run Deep

The St. John’s Dramatic Society (later called the Mimes and Mummers) mounted its first productions on December 8, 1855: Shakespeare’s Henry IV and Thomas Egerton Wilks’ romantic drama The Seven Clerks.

14. Edward Parade Was Named for a Professor of Military Science

The roots of Fordham’s ROTC program lie in the late 19th century, when Lt. Clarence R. Edwards was a professor of military science and tactics. He rose to command the 26th “Yankee” Division during World War I, and the green quad at the center of Rose Hill was later named in his honor.

The roots of Fordham’s ROTC program lie in the late 19th century, when Lt. Clarence R. Edwards was a professor of military science and tactics. He rose to command the 26th “Yankee” Division during World War I, and the green quad at the center of Rose Hill was later named in his honor.

15. Keating Hall Was an Instant Icon

With its great central clock tower and collegiate Gothic architecture, Keating Hall may seem medieval, but it wasn’t built until the mid-1930s. It served as the backdrop for the University’s commencement for the first time on June 10, 1936. The building opened in fall 1935 and was named for Joseph B. Keating, S.J., the University’s treasurer from 1910 to 1948.

With its great central clock tower and collegiate Gothic architecture, Keating Hall may seem medieval, but it wasn’t built until the mid-1930s. It served as the backdrop for the University’s commencement for the first time on June 10, 1936. The building opened in fall 1935 and was named for Joseph B. Keating, S.J., the University’s treasurer from 1910 to 1948.

16. Mass Transit Helped Us Grow

This panoramic image of Rose Hill, taken in 1916, shows the New York and Harlem Railroad (now Metro-North) and the Third Avenue Elevated line. The railroad was extended to the Fordham area in 1841, just a few months after the college opened, and the El reached Fordham in 1901. The proximity of both lines to the western edge of campus helped drive Fordham’s growth from a small college in a farming village into the Jesuit University of New York in its first six decades.

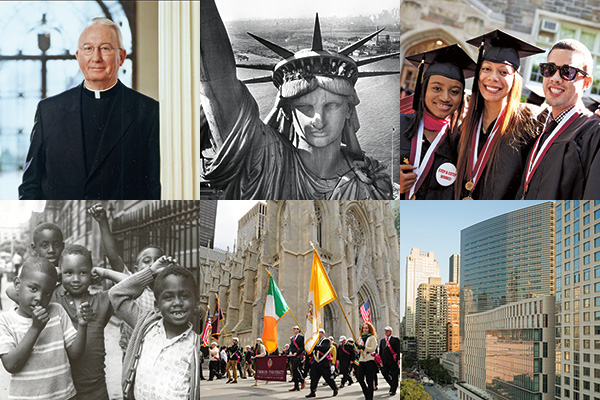

17. New York Grew Up Around Us

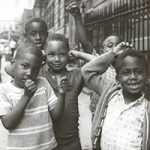

At 175 years old, Fordham has been around longer than some of the city’s most venerable landmarks and institutions, including the Brooklyn Bridge (opened in 1883) and the Statue of Liberty (dedicated in 1886). Since 1841, Fordham faculty, students, and alumni have helped endow the city with the restless energy, the sense of urgency and purpose that have come to define what it means to be a New Yorker.

At 175 years old, Fordham has been around longer than some of the city’s most venerable landmarks and institutions, including the Brooklyn Bridge (opened in 1883) and the Statue of Liberty (dedicated in 1886). Since 1841, Fordham faculty, students, and alumni have helped endow the city with the restless energy, the sense of urgency and purpose that have come to define what it means to be a New Yorker.

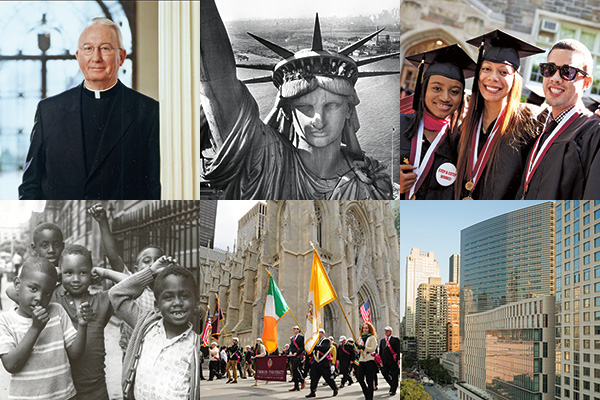

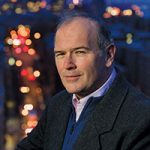

18. Father O’Hare Was Named One of the City’s Most Powerful People

As president from 1984 to 2003, Joseph A. O’Hare, S.J., GSAS ’68, helped transform the University from a strong regional, largely commuter school into what The Wall Street Journal called “a hard-charging institution.” He challenged Fordham to join “the dialogue with genius and passion that goes on every day” in the city. And he led by example, as the founding chair of the New York City Campaign Finance Board—a role that earned him a spot on a 1997 list of “New York’s 50 Most Powerful People.”

As president from 1984 to 2003, Joseph A. O’Hare, S.J., GSAS ’68, helped transform the University from a strong regional, largely commuter school into what The Wall Street Journal called “a hard-charging institution.” He challenged Fordham to join “the dialogue with genius and passion that goes on every day” in the city. And he led by example, as the founding chair of the New York City Campaign Finance Board—a role that earned him a spot on a 1997 list of “New York’s 50 Most Powerful People.”

19. Sister McGeady Revitalized Covenant House

When Fordham alumna Mary Rose McGeady, D.C., GSAS ’61, was named president and chief executive officer of Covenant House in 1990, the New York-based shelter for homeless

and runaway youths was in the middle of a financial and institutional crisis. She stared down a staggering $38 million debt and inspired a frustrated staff of 1,200 people to breathe new life into the agency’s programs and services.

When Fordham alumna Mary Rose McGeady, D.C., GSAS ’61, was named president and chief executive officer of Covenant House in 1990, the New York-based shelter for homeless

and runaway youths was in the middle of a financial and institutional crisis. She stared down a staggering $38 million debt and inspired a frustrated staff of 1,200 people to breathe new life into the agency’s programs and services.

By her retirement 13 years later, she had revitalized Covenant House and helped transform the lives of hundreds of thousands of children in 21 cities, including New York.

20. One Alumnus Helped Stem the Black Monday Crisis

As president of the New York Federal Reserve from 1985 to 1993, E. Gerald Corrigan, Ph.D., GSAS ’65, ’71, acted swiftly following the Black Monday stock market collapse in October 1987. His actions—including personal phone calls to jittery bankers, investors, and elected officials—are widely credited with keeping the crisis from spreading beyond Wall Street to other financial sectors.

As president of the New York Federal Reserve from 1985 to 1993, E. Gerald Corrigan, Ph.D., GSAS ’65, ’71, acted swiftly following the Black Monday stock market collapse in October 1987. His actions—including personal phone calls to jittery bankers, investors, and elected officials—are widely credited with keeping the crisis from spreading beyond Wall Street to other financial sectors.

In 1994, he joined Goldman Sachs, where he was a partner and managing director. He has credited his ability to work through problems and act decisively to his Jesuit education— first at Fairfield University, then at Fordham, where he earned a doctorate in economics. While it emphasizes the liberal arts and humanities, Jesuit education “puts even greater emphasis on simple, straightforward propositions of trying to teach you how to think,” he said. “That’s the genius of it.”

21. Our Bronx Black History Project Gives Voice to the Borough’s Rich Cultural Heritage

In November 2015, Fordham’s Bronx African American History Project made public a digital archive of more than 300 oral histories recorded by current and former Bronx residents—from 1950s homemakers to hip-hop pioneers—who have helped define the borough’s character.

In November 2015, Fordham’s Bronx African American History Project made public a digital archive of more than 300 oral histories recorded by current and former Bronx residents—from 1950s homemakers to hip-hop pioneers—who have helped define the borough’s character.

22. On St. Patrick’s Day, One of Fordham’s Own Will Lead the March Up Fifth Avenue

Next March, Michael Dowling, GSS ’74, president and CEO of Northwell Health (formerly North Shore-LIJ Health System), and a former professor and assistant dean at the Graduate School of Social Service, will serve as grand marshal of the 2017 New York City St. Patrick’s Day Parade.

Next March, Michael Dowling, GSS ’74, president and CEO of Northwell Health (formerly North Shore-LIJ Health System), and a former professor and assistant dean at the Graduate School of Social Service, will serve as grand marshal of the 2017 New York City St. Patrick’s Day Parade.

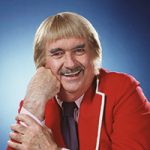

23. Students Thrive in CSTEP

For nearly 30 years, students have thrived in Fordham’s chapter of CSTEP—a New York state-sponsored program designed to propel underrepresented and economically disadvantaged scholars into careers in the sciences, health fields, and other licensed professions. In March 2012, scores of alumni returned to campus for a 25th anniversary dinner, eager to reunite and share success stories. One alumnus recalled, “CSTEP offered that feeling of community, of support, of being understood.”

Above from left: Asmaou Diallo with her fellow CSTEP graduates Amaidani Boncenor and Angel Melendez at commencement in 2012.

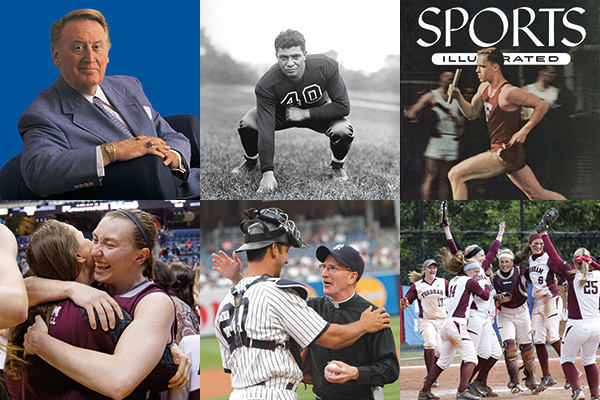

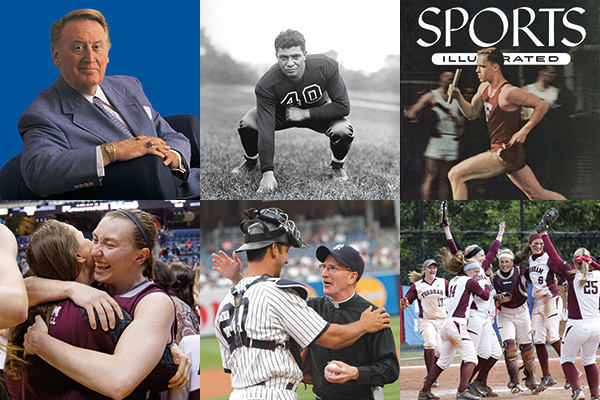

On October 26, 1947, Fordham dedicated its new radio station, WFUV, in a ceremony at Keating Hall. The station immediately became a home for future media stars, including Vin Scully, FCRH ’49, and Charles Osgood, FCRH ’54.

25. It’s No. 2 in the Country

WFUV is the second-best college radio station in the country, according to Princeton Review’s The Best 381 Colleges.

26. It’s a Professional Training Ground

Each year, 125 students are professionally trained in news and sports journalism, engineering, and production at the station. Since 2010, WFUV has earned more than 150 national and local awards for news and sports programming.

27. Fordham Loves Sunday Morning

Just like CBS Sunday Morning’s longtime host, Charles Osgood, FCRH ’54, who retired from the show last September, Emmy Award-winning producer Sara Kugel, FCRH ’11, got her start at Fordham’s WFUV. “Fordham will always feel like home to me,” she said.

28. Our Public Media Program Is New York’s First

This year, Fordham launched a master’s degree program in public media—the first in the city. It’s offered through the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partnership with WNET/Channel 13 public television and WFUV.

29. One of Our Alumni Was a Kangaroo

Bob Keeshan, UGE ’51, once said

that in creating his beloved Captain Kangaroo TV show, he operated “on

the conviction that [the audience]is composed of young children of potentially good taste, and that this taste should be developed.” That respect and admiration for our youngest citizens informed all

of Keeshan’s work, from his early days

as Clarabell the Clown on The Howdy Doody Show to his later work as a children’s author and advocate.

Bob Keeshan, UGE ’51, once said

that in creating his beloved Captain Kangaroo TV show, he operated “on

the conviction that [the audience]is composed of young children of potentially good taste, and that this taste should be developed.” That respect and admiration for our youngest citizens informed all

of Keeshan’s work, from his early days

as Clarabell the Clown on The Howdy Doody Show to his later work as a children’s author and advocate.

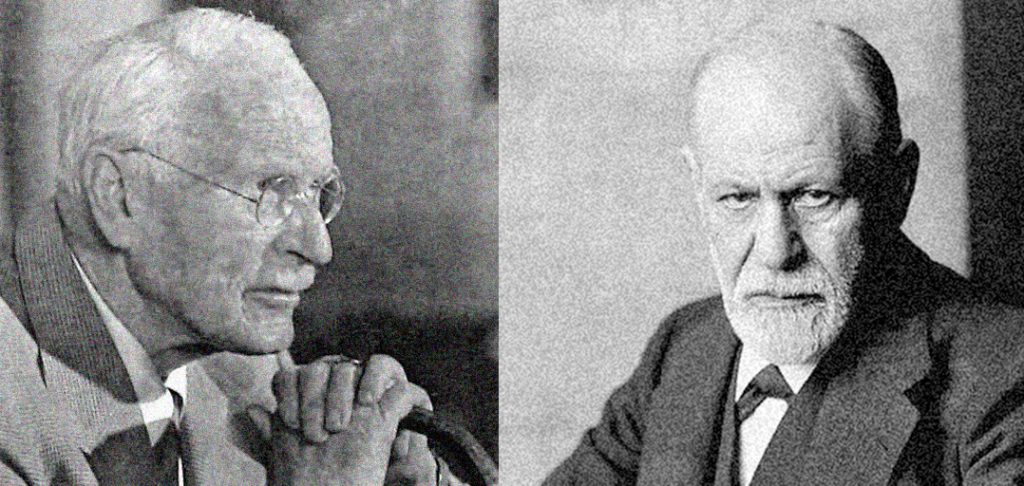

30. In the ’60s, We Knew “The Medium Is the Message”

The year was 1968: The Vietnam War was raging, the counterculture was flourishing, and media theorist Marshall McLuhan was teaching at Fordham. In the 1960s, he launched the idea that “the medium is the message,” equating the rise of electronic media with a revolution in thinking and group behavior.

31. We Ask That You “Please Don’t Squeeze the Charmin”

That line was the brainchild of John Chervokas, FCRH ’59. He was a 28-year- old copywriter for Benton & Bowles in 1964 when he created the campaign for toilet tissue that Advertising Age ranked as the 51st best of the 20th century. Watch on of the ads from the 1960s:

32. One Alumnus Helped Pioneer Cable Television

When he was majoring in physics at Fordham in the early 1950s, Herb Granath, FCRH ’54, GSAS ’55, saw an ad for a job as an NBC page. “I had no idea what that was,” said Granath, chairman emeritus of ESPN and former chairman of the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. But he applied anyway, and so began his distinguished career. He went on to lead ABC into the uncharted waters of cable television, heading ESPN and establishing A&E and the History channel.

33. America Magazine Was Founded by a Fordham Jesuit

In 1909, John J. Wynne, S.J., a Fordham professor, imagined a national Jesuit publication, one that would “discuss questions of the day” and help solve the “vital problems constantly thrust upon our people.” On April 17, 1909, America magazine was born. Nearly 120 years later, America is a vital media voice, and its current editor in chief, Matt Malone, S.J., GSAS ’07, is a Fordham alumnus.

In 1909, John J. Wynne, S.J., a Fordham professor, imagined a national Jesuit publication, one that would “discuss questions of the day” and help solve the “vital problems constantly thrust upon our people.” On April 17, 1909, America magazine was born. Nearly 120 years later, America is a vital media voice, and its current editor in chief, Matt Malone, S.J., GSAS ’07, is a Fordham alumnus.

34. One Alumna Is an ESPN Exec Who Champions Women

In December 2015, Forbes magazine named Christine Driessen, GABELLI ’77, the third most powerful woman in sports. As executive vice president and chief financial officer of ESPN, Driessen runs all of its financial operations worldwide. She has also championed the role of women at the company, starting a forum for female executives. A trustee fellow at Fordham, Driessen came back to the Rose Hill Gym in 2014 to give the women’s basketball team a pep talk before their appearance in the NCAA tournament. “Never sell yourself short,” she said,

“or take yourself out of the running.”

In December 2015, Forbes magazine named Christine Driessen, GABELLI ’77, the third most powerful woman in sports. As executive vice president and chief financial officer of ESPN, Driessen runs all of its financial operations worldwide. She has also championed the role of women at the company, starting a forum for female executives. A trustee fellow at Fordham, Driessen came back to the Rose Hill Gym in 2014 to give the women’s basketball team a pep talk before their appearance in the NCAA tournament. “Never sell yourself short,” she said,

“or take yourself out of the running.”

35. The Sultans of Stat Got Their Start as Fordham Undergrads

Fordham alumni Steve Hirdt, FCRH ’72, and Peter Hirdt, FCRH ’76, are the reigning Sultans of Stat. As executive vice president and vice president, respectively, of the Elias Sports Bureau, the Hirdt brothers help millions of people—from the casual fan to the hardcore fantasy leaguer—enjoy watching just about every sport, every day. Elias is the official statistician of Major League Baseball, the NFL, the NBA, the NHL, and MLS, and its many broadcast clients include ESPN.

36. A 1958 Alumnus Won the National Book Award

Bronx native Don DeLillo, FCRH ’58, has earned many of the literary world’s top honors, including a National Book Award for his 1985 novel, White Noise. In 2006, The New York Times named his 1997 masterpiece, Underworld, a runner-up for the best work of American fiction of the previous 25 years. And in 2013, he became the first person to receive the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction. The award “seeks to commend strong, unique, enduring voices that … have told us something about the American experience.”

Bronx native Don DeLillo, FCRH ’58, has earned many of the literary world’s top honors, including a National Book Award for his 1985 novel, White Noise. In 2006, The New York Times named his 1997 masterpiece, Underworld, a runner-up for the best work of American fiction of the previous 25 years. And in 2013, he became the first person to receive the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction. The award “seeks to commend strong, unique, enduring voices that … have told us something about the American experience.”

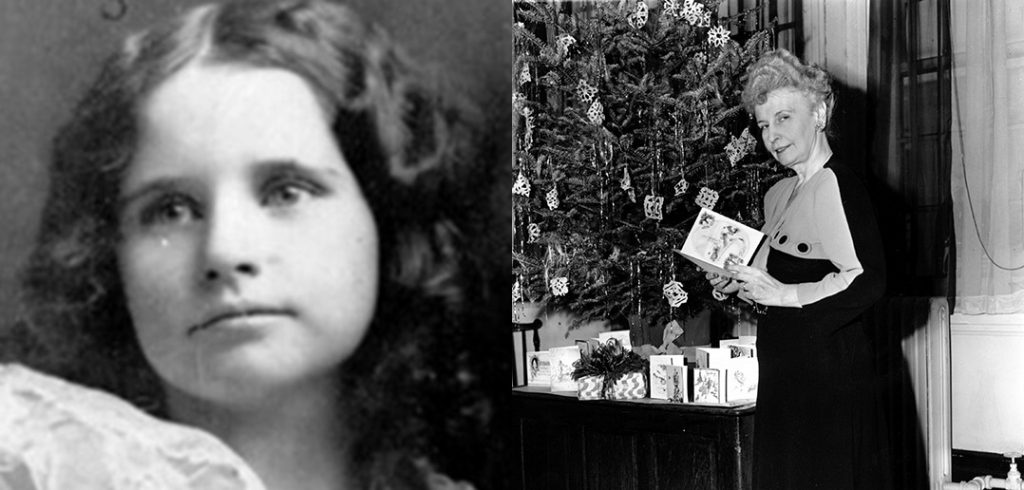

37. The “Queen of Suspense” Is a Class Act

“I can’t sing or dance, but I can tell a story,” Mary Higgins Clark, FCLC ’79, once told a group of Fordham students. “It’s my one gift.” Clark overcame tragedy—the sudden death of her husband, the father of her five children—to become one of the most accomplished writers of our time. She’s the author of more than 30 bestselling novels, a feat that has earned her the nickname “Queen of Suspense.” When Clark’s eldest children entered college, she, too, felt drawn to higher education. So she enrolled at Fordham in the early 1970s, earning a degree in philosophy summa cum laude in 1979.

“I can’t sing or dance, but I can tell a story,” Mary Higgins Clark, FCLC ’79, once told a group of Fordham students. “It’s my one gift.” Clark overcame tragedy—the sudden death of her husband, the father of her five children—to become one of the most accomplished writers of our time. She’s the author of more than 30 bestselling novels, a feat that has earned her the nickname “Queen of Suspense.” When Clark’s eldest children entered college, she, too, felt drawn to higher education. So she enrolled at Fordham in the early 1970s, earning a degree in philosophy summa cum laude in 1979.

38. Our University Press Is the Oldest at a U.S. Catholic University

In 1907, Fordham established a university press to disseminate scholarly research. Today it’s the oldest press at a U.S. Catholic university, publishing 60 to 70 books a year, primarily in the humanities.

39. One Alumnus Is a Master of the Art and Science M*A*S*H*-Up

Generations of Americans will always remember Alan Alda, FCRH ’56, for his beloved and cocky Captain Hawkeye Pierce of the TV show M*A*S*H. But he is also passionate about science education. From 1993 to 2005, he helped broaden the public’s understanding of science as host of the acclaimed PBS program Scientific American Frontiers, and he helped establish the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University, where he uses improvisation techniques to help scientists communicate more effectively.

Generations of Americans will always remember Alan Alda, FCRH ’56, for his beloved and cocky Captain Hawkeye Pierce of the TV show M*A*S*H. But he is also passionate about science education. From 1993 to 2005, he helped broaden the public’s understanding of science as host of the acclaimed PBS program Scientific American Frontiers, and he helped establish the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University, where he uses improvisation techniques to help scientists communicate more effectively.

40 to 42. Three Alumni Have Earned the Pulitzer Prize

40. The Sportswriter

New York Times sports columnist Arthur Daley, FCRH ’26, was the first Fordham graduate to win a Pulitzer Prize—and one of only a handful of sportswriters ever to win the prestigious award. He was honored in 1956 for “outstanding coverage and commentary on the world of sports.”

New York Times sports columnist Arthur Daley, FCRH ’26, was the first Fordham graduate to win a Pulitzer Prize—and one of only a handful of sportswriters ever to win the prestigious award. He was honored in 1956 for “outstanding coverage and commentary on the world of sports.”

41. The Investigative Journalist

Loretta Tofani, FCRH ’75, received the local specialized reporting Pulitzer Prize for a series titled “Rape in the County Jail.” In 1982, as a metropolitan staff reporter for The Washington Post, she detailed a pattern of rape and sexual assault of prisoners awaiting trial at the Prince George’s County, Maryland, Detention Center.

Loretta Tofani, FCRH ’75, received the local specialized reporting Pulitzer Prize for a series titled “Rape in the County Jail.” In 1982, as a metropolitan staff reporter for The Washington Post, she detailed a pattern of rape and sexual assault of prisoners awaiting trial at the Prince George’s County, Maryland, Detention Center.

42. The Compelling and Compassionate Columnist

Jim Dwyer, FCRH ’79, has won two Pulitzer Prizes. He earned his first

one for spot news reporting as part of

the Newsday team that covered the deadly 1991 Union Square subway derailment. And in 1995, he received the commentary prize for “his compelling and compassionate columns about New York City” for Newsday. Since April 2007, Dwyer has been writing the “About New York” column for The New York Times.

Jim Dwyer, FCRH ’79, has won two Pulitzer Prizes. He earned his first

one for spot news reporting as part of

the Newsday team that covered the deadly 1991 Union Square subway derailment. And in 1995, he received the commentary prize for “his compelling and compassionate columns about New York City” for Newsday. Since April 2007, Dwyer has been writing the “About New York” column for The New York Times.

43. We’re No. 7 in Student Journalism

Fordham’s student newspapers—including The Ram and The Observer—are among the country’s best, coming in at No. 7, according to Princeton Review’s The Best 381 Colleges.

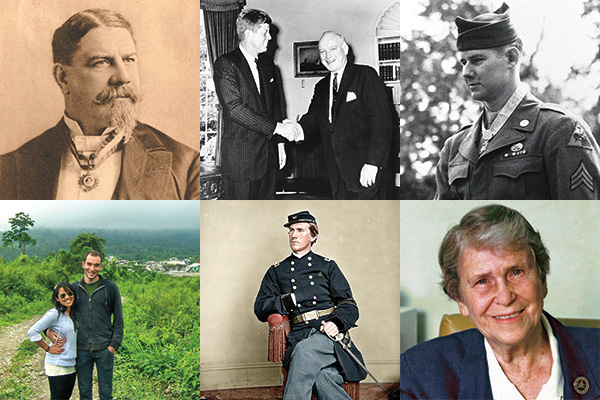

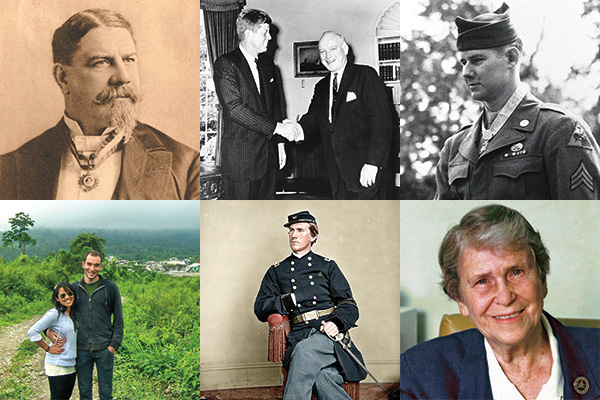

Not only have Fordham alumni served the nation in every conflict since the Civil War, but six have earned the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award: three for service during the Civil War, one during World War II, and two during the Vietnam War.

Gen. Jack Keane, GABELLI ’66, a retired four-star general and a former vice chief of staff of the U.S. Army, has called that “quite extraordinary.”

“I really believe we should take a hard look at Fordham in terms of those who have served in the military,” he has said. “They are not about war. They are about selfless service. In my judgment, they do it for a simple yet profound sense of duty, and they do it for one another. We can never take that for granted.”

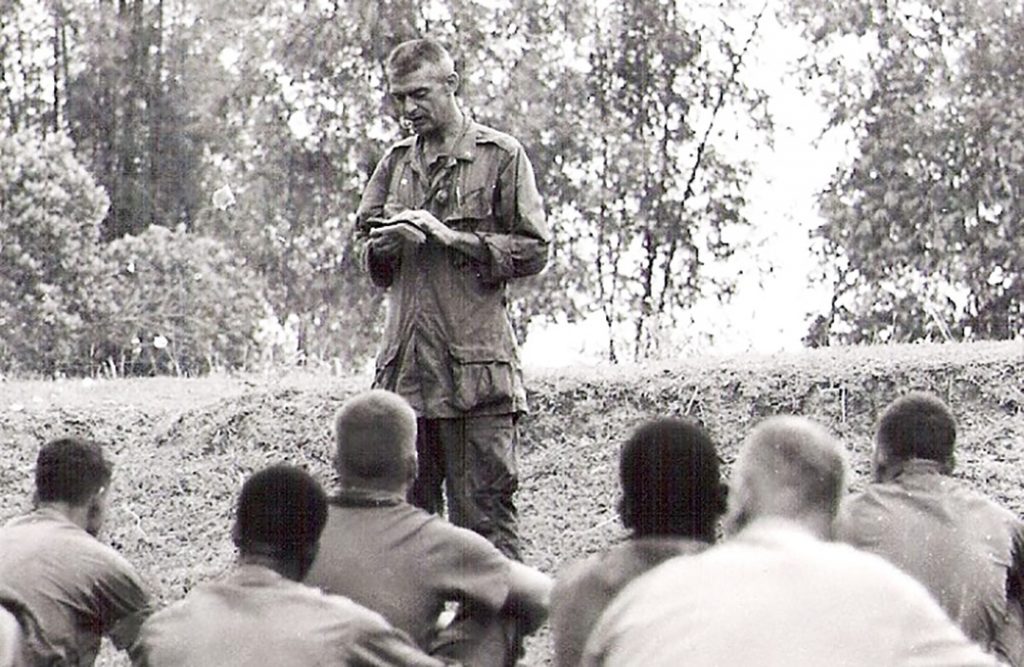

44. The Grunt Padre

Though he never signed on for combat, Father Vincent Capodanno was a Vietnam War hero in the truest sense—a military chaplain, affectionately known as “the Grunt Padre,” who exhibited unparalleled bravery and never left the side of his men.

When he heard the North Vietnamese had ambushed his Marines, he rushed to the scene of the September 1967 battle in the Que Son Valley. A mortar shell shredded his right arm, yet the chaplain braved the heavy artillery to drag a hurt sergeant to safety. He quickly moved among the wounded and the dead, praying with the men and giving last rites to his fallen brothers, before he made the ultimate sacrifice. He was 38 years old.

Capodanno, who took evening classes at Fordham, received the Medal of Honor posthumously in January 1969. In 2006, the Archdiocese for the Military Services declared him a Servant of God, initiating the cause for his sainthood.

45. A Hero and an Advocate for Vets

As a U.S. Army medic during World War II, Brooklyn native Thomas J. Kelly, UGE ’56, LAW ’62, saved 17 lives on April 5, 1945, by showing “gallantry and intrepidity in the face of seemingly certain death.” So reads his citation for the Medal of Honor, which he received seven months later. He would show that same spirit of service for the rest of his life by helping veterans and others who were affected by that titanic conflict.

As a U.S. Army medic during World War II, Brooklyn native Thomas J. Kelly, UGE ’56, LAW ’62, saved 17 lives on April 5, 1945, by showing “gallantry and intrepidity in the face of seemingly certain death.” So reads his citation for the Medal of Honor, which he received seven months later. He would show that same spirit of service for the rest of his life by helping veterans and others who were affected by that titanic conflict.

Soon after the war, he enrolled at Fordham, working his way through the Undergraduate School of Education over 10 years. After earning a Fordham law degree in 1962, he worked for the Veterans Administration for 36 years. He raised a family with his wife, Wilma; co-founded the Congressional Medal of Honor Society and served as its president; set up a fund to help widows and orphans of medal recipients; and organized events to raise money for veterans’ benefit. He died in 1988 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Mention of his medal made him think of the sacrifices of others, as was clear in his 1987 interview for the U.S. Army Medical Department’s oral history program: “I feel so bad,” he said, “about all the fellows that performed all those deeds deserving the Medal of Honor, who were never seen.”

46. A Noted Scholar and Judge

Martin T. McMahon graduated from Fordham in 1855 and, like many of his classmates, was drawn into the Civil War. In 1891, he received the Medal of Honor for bravery in the fighting near White Oaks Swamp, Virginia, on June 30, 1862. “Under fire of the enemy,” his citation reads, he “destroyed a valuable train that had been abandoned and prevented it from falling into the hands of the enemy.”

Martin T. McMahon graduated from Fordham in 1855 and, like many of his classmates, was drawn into the Civil War. In 1891, he received the Medal of Honor for bravery in the fighting near White Oaks Swamp, Virginia, on June 30, 1862. “Under fire of the enemy,” his citation reads, he “destroyed a valuable train that had been abandoned and prevented it from falling into the hands of the enemy.”

After the war, he served as corporation counsel for New York City, and in 1896 he was elected judge of the Court of General Sessions. Upon his death in 1906, The New York Times described him as a “noted soldier and judge” and “one of the conspicuous figures of the Civil War.”

47. A Leader of Men

Robert Murray distinguished himself as a leader early in his short life—a distinction he would carry through to his last breath, in Vietnam, at the age of 23.

Robert Murray distinguished himself as a leader early in his short life—a distinction he would carry through to his last breath, in Vietnam, at the age of 23.

One of six children in a devout Catholic family, Murray attended Fordham Prep, where he served as a class officer for all four years and graduated with honors in 1964. Four years later, he earned a bachelor’s degree at Fordham College at Rose Hill.

On June 7, 1970, as an Army squad leader, he was searching for enemy mortar near the village of Hiep Duc when a soldier tripped an enemy grenade. “Instantly assessing the danger to the men of his squad,” his Medal of Honor citation reads, “Staff Sgt. Murray unhesitatingly and with complete disregard for his own safety, threw himself on the grenade, absorbing the full and fatal impact of the explosion. By his gallant action and self-sacrifice, he prevented the death or injury of the other members of his squad.”

48. A Man of Great Generosity

After completing his studies at Fordham in 1862, Edwin M. Neville enlisted in the Union army. He was soon discharged due to an unspecified disability, but reenlisted in 1864 and rose to captain. He earned the Medal of Honor for capturing a Confederate flag at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek on April 6, 1865. Three days later, he was among those who escorted Union general Ulysses S. Grant to Appomattox Court House, where Grant accepted the surrender of Confederate general Robert E. Lee.

After completing his studies at Fordham in 1862, Edwin M. Neville enlisted in the Union army. He was soon discharged due to an unspecified disability, but reenlisted in 1864 and rose to captain. He earned the Medal of Honor for capturing a Confederate flag at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek on April 6, 1865. Three days later, he was among those who escorted Union general Ulysses S. Grant to Appomattox Court House, where Grant accepted the surrender of Confederate general Robert E. Lee.

Neville died in 1886 at the age of 43. An obituary writer praised him as “a man of great generosity, good address … and excellent business tact. And these qualities made him successful in almost anything he undertook.”

49. An Irish-American Patriot

As class valedictorian in 1853, James R. O’Beirne exhorted his fellow Fordham graduates to honor their country and their alma mater. During the Civil War, he would show his Fordham loyalty when he brought coffee and Irish stew to captured former classmates who were serving in the Confederate Army.

As class valedictorian in 1853, James R. O’Beirne exhorted his fellow Fordham graduates to honor their country and their alma mater. During the Civil War, he would show his Fordham loyalty when he brought coffee and Irish stew to captured former classmates who were serving in the Confederate Army.

O’Beirne served in the 37th New York Regiment, the famed “Irish Rifles.” In 1863, he was seriously wounded at Chancellorsville, Virginia, and lay on the battlefield for three days. After recovering, he was made provost marshal of Washington, D.C., and in 1865 was involved in the pursuit that led to the capture of John Wilkes Booth, President Abraham Lincoln’s assassin. He received the Medal of Honor in 1891 for having “gallantly maintained the line of battle until ordered to fall back” at Fair Oaks, Virginia, in 1862.

After the war, O’Beirne worked in Washington, D.C., but left in 1890 to become U.S. commissioner of immigration at the Port of New York, where his duties included administration of the Ellis Island Immigration Examination Station. His return to the city of his youth allowed him to visit Rose Hill, where he impressed Fordham students with, as one undergraduate recalled, his “manly beauty … enhanced by a grandeur of soul.”

50. We Tie a Yellow Ribbon ’Round Our Ole Oak Tree

Approximately 400 military veterans and their dependents are enrolled at Fordham each year. Despite a national cap on VA benefits, Fordham has increased its Yellow Ribbon commitment to cover 100 percent of tuition and mandatory fees for all fully eligible post-9/11 veterans and their dependents.

51 to 54. Four Alumni Have Received the Medal of Freedom, the Nation’s Highest Civilian Award

On November 22, 2016, Vin Scully, FCRH ’49, became the fifth Fordham graduate to receive the honor. See this story about the award ceremony. See also item No. 136 in this feature, “Vin Scully Is the Dean of Fordham-Trained Sportscasters.”

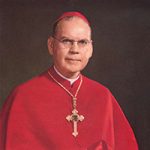

51. A Man of Courage

Terence Cardinal Cooke, GSAS ’57,

was born in New York City in 1921

and ordained a Catholic priest in 1945 by Fordham alumnus Francis Cardinal Spellman, archbishop of New York. During the early 1950s, Cooke taught

at Fordham’s Graduate School of Social Service. After Cardinal Spellman’s death in late 1968, at the height of the Vietnam War, Cooke was named archbishop of New York and, later, military vicar to the U.S. armed forces. He died of leukemia in 1983, and one year later, President Ronald Reagan awarded him the Medal of Freedom posthumously, calling him a “man of compassion, courage, and personal holiness.”

Terence Cardinal Cooke, GSAS ’57,

was born in New York City in 1921

and ordained a Catholic priest in 1945 by Fordham alumnus Francis Cardinal Spellman, archbishop of New York. During the early 1950s, Cooke taught

at Fordham’s Graduate School of Social Service. After Cardinal Spellman’s death in late 1968, at the height of the Vietnam War, Cooke was named archbishop of New York and, later, military vicar to the U.S. armed forces. He died of leukemia in 1983, and one year later, President Ronald Reagan awarded him the Medal of Freedom posthumously, calling him a “man of compassion, courage, and personal holiness.”

52. An Advocate for the Poor

Sister M. Isolina Ferré, GSAS ’61, was born in Ponce, Puerto Rico, in 1914,

the youngest daughter of one of Puerto Rico’s wealthiest families. She entered the Missionary Servants of the Holy Trinity in 1935. In the 1950s, her work as a nun brought her to New York, where she earned a master’s degree in sociology at Fordham while gaining national recognition for her work with Puerto Rican youth gangs in Brooklyn.

Sister M. Isolina Ferré, GSAS ’61, was born in Ponce, Puerto Rico, in 1914,

the youngest daughter of one of Puerto Rico’s wealthiest families. She entered the Missionary Servants of the Holy Trinity in 1935. In the 1950s, her work as a nun brought her to New York, where she earned a master’s degree in sociology at Fordham while gaining national recognition for her work with Puerto Rican youth gangs in Brooklyn.

She later established community aid centers in Ponce, and in 1988 founded Trinity College of Puerto Rico, a school that provides leadership and vocational training. In August 1999, President Bill Clinton awarded her the Medal of Freedom, praising her ability to combine “her deep religious faith with her compassionate and creative advocacy for the disadvantaged.”

53. Father Mercy

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines from 1942 to 1945, when internment camps around Manila swelled with civilians and Allied prisoners, one Jesuit priest earned the nickname “Father Mercy” for his efforts to ease their suffering. The heroic work of that priest, John Fidelis Hurley, S.J., a 1914 Fordham graduate, would have an enduring impact on the welfare of the Philippine people.

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines from 1942 to 1945, when internment camps around Manila swelled with civilians and Allied prisoners, one Jesuit priest earned the nickname “Father Mercy” for his efforts to ease their suffering. The heroic work of that priest, John Fidelis Hurley, S.J., a 1914 Fordham graduate, would have an enduring impact on the welfare of the Philippine people.

A native of New York City, Father Hurley served on the faculty of the Ateneo de Manila in the Philippines and in 1936 was named superior of the Jesuit mission in the country, a role he was performing when Japan invaded the Philippines in 1941.

Father Hurley not only resisted Japanese attempts to confiscate the Ateneo de Manila property but also ran a smuggling network that delivered food, medicine, and money to civilians and Allied soldiers being held in internment camps around Manila. He was eventually interrogated by the Japanese and interned in the Santo Tomas camp until 1945, when it was liberated by the U.S. Army.

He received the Medal of Freedom for his wartime efforts, and later served as the first secretary general of the Catholic Welfare Organization, a forerunner of Catholic Relief Services in the Philippines.

54. A Civil Rights Judge

Irving R. Kaufman, FCRH ’28, LAW ’31, is perhaps best known as the federal judge who sentenced Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to death on April 5, 1951. But he also ruled in some landmark First Amendment, antitrust, and civil rights cases during four decades on the bench.

Irving R. Kaufman, FCRH ’28, LAW ’31, is perhaps best known as the federal judge who sentenced Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to death on April 5, 1951. But he also ruled in some landmark First Amendment, antitrust, and civil rights cases during four decades on the bench.

When he died in 1992 at age 81, The New York Times wrote, “It was Judge Kaufman’s hope that he would be remembered for his role not in the Rosenberg case, the espionage trial of the century, but as the judge whose order was the first to desegregate a public school in the North, who was instrumental in streamlining court procedures, who rendered innovative decisions in antitrust law and, most of all, whose rulings expanded the freedom of the press.”

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan awarded Kaufman the Medal of Freedom for his “exemplary service to our country” and “his multifaceted effort to promote an understanding of the law and our legal tradition.”

55. The Real-Life Hero of Bridge of Spies Went to Fordham

From the 1940s until his untimely death in 1970, James B. Donovan brought intelligence, integrity, and courage to bear on some of the seminal events of his time. He is perhaps best known for giving legal representation to an accused Soviet spy, a principled but unpopular act that would later allow him to bring off one of the most famous “spy swaps” in history. This remarkable story is told in his bestselling memoir, Strangers on a Bridge, and in the 2015 film Bridge of Spies, which stars Tom Hanks as Donovan.

From the 1940s until his untimely death in 1970, James B. Donovan brought intelligence, integrity, and courage to bear on some of the seminal events of his time. He is perhaps best known for giving legal representation to an accused Soviet spy, a principled but unpopular act that would later allow him to bring off one of the most famous “spy swaps” in history. This remarkable story is told in his bestselling memoir, Strangers on a Bridge, and in the 2015 film Bridge of Spies, which stars Tom Hanks as Donovan.

Donovan died from a heart attack at age 53 on January 19, 1970. At the funeral Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, Robert I. Gannon, S.J., former president of Fordham, shared his impressions of the “quiet, shrewd” former student: “I came to know Jim Donovan as the kind of student we had in mind when we started the place in 1841, the kind we wanted to graduate in 1937: intelligent, fearless, and good.”

56. The Real-Life Hero of Glory Was a Rose Hill Alumnus

Born into a wealthy Boston family, Robert Gould Shaw attended the second division of St. John’s College, now known as Fordham Prep, after his family moved to New York in 1847.

Born into a wealthy Boston family, Robert Gould Shaw attended the second division of St. John’s College, now known as Fordham Prep, after his family moved to New York in 1847.

During the Civil War, he commanded the historic 54th Massachusetts Regiment, one of the first official regiments of black troops in the U.S. military. On July 18, 1863, along with two brigades of white troops, the 54th stormed the heavily guarded Fort Wagner, just outside of Charleston, South Carolina. Although Shaw was killed in battle with his men, his and his regiment’s bravery were immortalized by the 1989 film Glory, which featured Fordham alumnus Denzel Washington, FCLC ’77, in an Academy Award-winning performance as a fugitive slave who served in the regiment.

57. An Alumnus Helped Advance Peace in Northern Ireland

Optimism, faith, and an unwavering devotion to his family’s Irish heritage have inspired William J. Flynn, GSAS ’51, chairman emeritus of Mutual of America, to commit much of his lifetime to ending the violent conflict in Northern Ireland.

Optimism, faith, and an unwavering devotion to his family’s Irish heritage have inspired William J. Flynn, GSAS ’51, chairman emeritus of Mutual of America, to commit much of his lifetime to ending the violent conflict in Northern Ireland.

During the early 1990s, in an effort to help end the violence, Flynn sponsored a series of ads in The New York Times titled “Irish eyes are crying for peace.” This and other efforts paid off. In 1994, he attended both the IRA and Loyalist ceasefire announcements. And in 2010, Mary McAleese, then president of Ireland, praised Flynn, writing, “His contribution to the Peace Process in Northern Ireland has been simply immense.”

58. Sargent Shriver Has a Fordham Legacy

In February 1962, Sargent Shriver, the founding director of the Peace Corps, visited Fordham’s Rose Hill campus and told more than 700 students that the function of the new volunteer program was “to make a substantial contribution to humanity and to world peace,” The Ram reported. “We are in a struggle,” he said. “The traditional, ordinary, pedestrian way of doing things has got to be junked.”

In February 1962, Sargent Shriver, the founding director of the Peace Corps, visited Fordham’s Rose Hill campus and told more than 700 students that the function of the new volunteer program was “to make a substantial contribution to humanity and to world peace,” The Ram reported. “We are in a struggle,” he said. “The traditional, ordinary, pedestrian way of doing things has got to be junked.”

While it’s impossible to know how many Fordham students Shriver inspired that day, or on subsequent visits, his words did make a lasting impression on Ann Sheehan, UGE ’65, former executive director of Pennsylvania’s BCTV.

“Sarge hooked me completely,” she wrote upon his death in 2011. “There were applications available right there, in the gym, and I made my friend wait for me while I filled it out.” She served for two years in Togo, where she taught English as a second language. “It was a life-changing experience,” she wrote, “which is a statement made by just about everyone who’s been in the Peace Corps.”

59. 446 Alumni Have Served in the Peace Corps

In February 2016, Fordham was named to the list of universities that produce the most volunteers for the Peace Corps. With 15 alumni now serving worldwide, Fordham comes in at No. 18 out of 25 on the list of medium-size universities. As of fall 2016, a total of 446 Fordham alumni have served in the Peace Corps since its founding in 1961, including Joannah Caneda, FCRH ’06, LAW ’14, and Rob Gunther, FCRH ’06 (above), who were married in 2008 and served together in Ecuador.

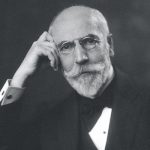

The Fordham Libraries contain 22 maps of Dutch New York and early New England, including the one shown above, which was made in 1671. The maps were a gift from Bert Twaalfhoven, GABELLI ’52, who grew up in the Hague and whose family lost everything when their home was bombed during World War II. In 1948, Robert I. Gannon, S.J., then president of Fordham, gave Twaalfhoven a scholarship to the University. “I left Holland on the SS Volendam with $20 in pocket money,” he has written, calling Fordham “a life-changing experience.” He later earned an M.B.A. at Harvard and went on to a long career as an entrepreneur and venture capitalist.

61. George Washington’s Papers and John Trumbull’s Drawings Are Here

The Declaration of Independence, 4 July 1776 (above) is perhaps the best-known painting by John Trumbull (1756–1843), widely considered one of the founding fathers of American Art. The Fordham University Libraries’ Charles Allen Munn Collection of Early Americana includes 36 Trumbull drawings as well as 58 letters, diaries, and papers of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Paul Revere, and others of the Revolutionary period.

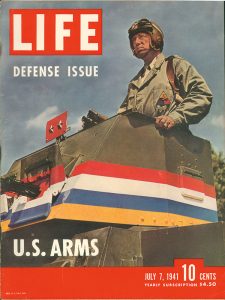

62. Hellzapoppin’ Was “The Greatest LIFE Photographer”

One of the Fordham Libraries’ treasures is a complete collection of LIFE magazines, a gift of the late George Weisskopf, FCRH ’41. That includes the July 7, 1941, issue featuring Gen. George S. Patton in a cover photo taken by Fordham alumnus Eliot Elisofon, GABELLI ’33. Elisofon—or Hellzapoppin’, as Patton called him—grew up on the Lower East Side, a son of Latvian Jewish immigrants. As a teen, he worked to support his family and took night classes at Fordham, earning a B.S. in 1933. By the time he crossed paths with Patton, he was in the habit of calling himself “the greatest LIFE photographer.” When one of his editors at the magazine told him he really should stop doing that, Elisofon agreed. “You’re right,” he reportedly said. “You should be doing it for me.”

One of the Fordham Libraries’ treasures is a complete collection of LIFE magazines, a gift of the late George Weisskopf, FCRH ’41. That includes the July 7, 1941, issue featuring Gen. George S. Patton in a cover photo taken by Fordham alumnus Eliot Elisofon, GABELLI ’33. Elisofon—or Hellzapoppin’, as Patton called him—grew up on the Lower East Side, a son of Latvian Jewish immigrants. As a teen, he worked to support his family and took night classes at Fordham, earning a B.S. in 1933. By the time he crossed paths with Patton, he was in the habit of calling himself “the greatest LIFE photographer.” When one of his editors at the magazine told him he really should stop doing that, Elisofon agreed. “You’re right,” he reportedly said. “You should be doing it for me.”

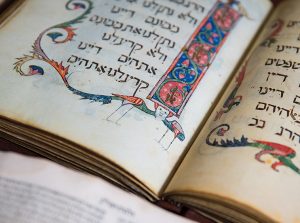

63. We Have a Judaica Collection

In November 2015, Fordham installed Magda Teter, Ph.D., as the inaugural Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies—a position created with a $3 million gift from Fordham alumnus Eugene Shvidler, GABELLI ’92. Since then, she has been assembling a collection of rare Hebrew scrolls and books. “My students are always shocked when I bring a 500-year-old book to class,” she says. “They’ve never touched something that old.” This fall, the University launched an interdisciplinary minor in Jewish studies, and with support from an additional gift from Shvidler, Fordham will soon establish a Jewish studies center.

64. Our Website Hosts a Repository of Primary Documents from the Middle Ages to the Present

In 1996, when the web was still in its infancy, Fordham’s Center for Medieval Studies helped graduate student Paul Halsall, GSAS ’99, bring dusty old texts into the digital age. Since then, Fordham’s Internet History Sourcebooks have earned a global reputation as a go-to source for reliable English-language translations of primary documents from the Middle Ages to the present, accounting for more than 500,000 monthly visits to Fordham’s website. “The large number of graduate applications we get because of the Sourcebooks shows [their]true reach,” said Maryanne Kowaleski, Ph.D., Fordham’s Joseph Fitzpatrick, S.J., Distinguished Professor of History and Medieval Studies.

65. Our Museum’s Ancient Objects Give Students a Feel for the Classics

The Fordham Museum of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Art— dedicated in December 2007—features 260 antiquities dating from the seventh century B.C. through the third century A.D. The collection was donated to the University by alumnus William D. Walsh, FCRH ’51, and his wife, Jane, from their private collection. Walsh, a lawyer and venture capitalist, studied Greek and Latin at Fordham. “If you are a classics major or minor, as I was, you can’t get a feel for classics in books alone,” he said at the museum’s opening. “Seeing [the objects]gives people a feel for it.”

The Fordham Museum of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Art— dedicated in December 2007—features 260 antiquities dating from the seventh century B.C. through the third century A.D. The collection was donated to the University by alumnus William D. Walsh, FCRH ’51, and his wife, Jane, from their private collection. Walsh, a lawyer and venture capitalist, studied Greek and Latin at Fordham. “If you are a classics major or minor, as I was, you can’t get a feel for classics in books alone,” he said at the museum’s opening. “Seeing [the objects]gives people a feel for it.”

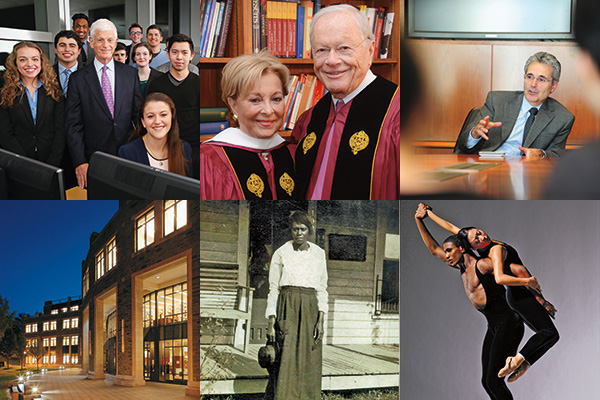

A $10 million gift from William D. Walsh, FCRH ’51, supported the construction of the William D. Walsh Family Library, which was officially dedicated at Rose Hill on October 17, 1997.

67. Endowed Chairs Are on the Rise

In the past decade, Fordham has established 41 endowed chairs, bringing the total number to 67. These faculty positions—many of them donor-funded—are in a wide range of subjects, including quantitative psychology, global security analysis, Orthodox Christian studies, and international human rights.

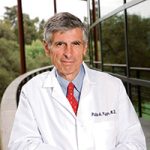

68. An Alumnus Leads the Fight Against Cancer

In September 2011, Ronald A. DePinho, M.D., FCRH ’77, became president of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, the world’s largest and perhaps most renowned cancer hospital. One year later, he announced that MD Anderson would launch the Moon Shots Program, a $3 billion initiative to dramatically reduce cancer deaths over the next decade.

In September 2011, Ronald A. DePinho, M.D., FCRH ’77, became president of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, the world’s largest and perhaps most renowned cancer hospital. One year later, he announced that MD Anderson would launch the Moon Shots Program, a $3 billion initiative to dramatically reduce cancer deaths over the next decade.

69. We Educate First-Generation Students

Approximately one in five undergraduates in Fordham’s Class of 2019 is the first in their family to attend college.

70. A Fordham Philosopher Leads the “Varieties of Understanding” Project

In 2013, philosophy professor Stephen R. Grimm, Ph.D., earned a $4.2 million grant from the Templeton Foundation to develop a better understanding of understanding itself. The award has funded new research in philosophy, psychology, and theology.

71. One Student Created a Novel Way to Honor Enslaved Americans

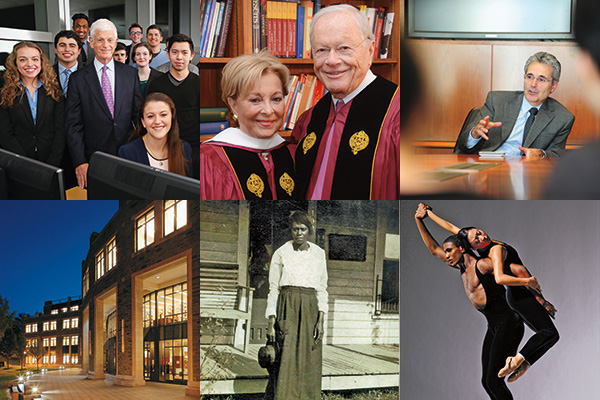

As a student at Fordham’s School of Professional and Continuing Studies, Sandra Arnold, PCS ’13, launched the National Burial Database of Enslaved Americans. She got the idea after discovering a plantation cemetery in Tennessee that contains the graves of her enslaved ancestors. Arnold is now a graduate fellow at Brown University’s Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, and her database is the core project of her Periwinkle Initiative (periwinkleinitiative.org).

As a student at Fordham’s School of Professional and Continuing Studies, Sandra Arnold, PCS ’13, launched the National Burial Database of Enslaved Americans. She got the idea after discovering a plantation cemetery in Tennessee that contains the graves of her enslaved ancestors. Arnold is now a graduate fellow at Brown University’s Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, and her database is the core project of her Periwinkle Initiative (periwinkleinitiative.org).

72. An Alumnus Helped Write the 25th Amendment

As a recent Fordham Law graduate in the mid-1960s, John Feerick, FCRH ’58, LAW ’61, helped draft and secure the passage of the 25th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, dealing with presidential disability and succession. He served as dean of Fordham Law from 1982 to 2002, and today he is the founding director of the school’s Feerick Center for Social Justice.

As a recent Fordham Law graduate in the mid-1960s, John Feerick, FCRH ’58, LAW ’61, helped draft and secure the passage of the 25th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, dealing with presidential disability and succession. He served as dean of Fordham Law from 1982 to 2002, and today he is the founding director of the school’s Feerick Center for Social Justice.

73. A 19th-Century Alumnus Raised Stained-Glass Making to New Heights

John LaFarge became interested in art during his studies at St. John’s College, Fordham, in the 1850s. He later exhibited paintings at the National Academy in New York City, but his inquisitive mind led him to experiment with stained glass. With the introduction of opalescent glass and other materials, LaFarge lifted the medium to previously unimaginable heights. For his innovative work, he was one of the first seven men chosen for membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

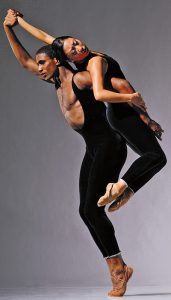

74. We’ve Been Dancing with Alvin Ailey Since 1998

74. We’ve Been Dancing with Alvin Ailey Since 1998

In fall 1998, Fordham College at Lincoln Center partnered with the Ailey School to create the Ailey/Fordham B.F.A. program in dance. The program blends the rigors of a liberal arts education at Fordham with conservatory training at the official school of the internationally acclaimed Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Since taking their first steps together, Fordham and Ailey have graduated more than 250 students, many who have gone on to work as professional dancers.

75. Mario Gabelli’s $25 Million Gift Is the Largest to Date

On September 25, 2010, before the annual Homecoming football game, Fordham announced that renowned value investor and 1965 Fordham alumnus Mario Gabelli had made a historic $25 million gift to enhance business education at Fordham. It’s the largest single contribution the University has received to date.

76. A Bequest Helped Build a Home for Students at Lincoln Center

Elodie Huston (left) and her roommate Sithumi Narasinghe Priya Dewage were among the first residents of McKeon Hall when it opened in 2014. The construction of the 12-story hall was made possible in part by a generous bequest from the late Robert McKeon, GABELLI ’76, a former Fordham trustee.

77. Campbell, Salice, and Conley Halls Were Named in Honor of Two Generous Couples and Their Families

In August 2010, the first group of 400-plus Fordham students moved into Campbell, Salice, and Conley residence halls, which were built thanks to the generosity of two couples: Susan Conley Salice, FCRH ’82, and Thomas P. Salice, GABELLI ’82; and Joan M. Campbell and Robert E. Campbell, GABELLI ’55.

78. An Alumna Is an Expert on the Power of Games

Game designer and researcher Jane McGonigal, Ph.D., FCLC ’99, has been named one of the “10 Most Powerful Women to Watch” by Forbes and one of the “20 Most Inspiring Women in the World” by O Magazine. “Games train us,” she wrote in her 2015 book SuperBetter, to think and act in ways that “help us turn extreme stress and challenge into positive transformation.”

79. Our Alumni Understand the Power of Scholarships

Like many Fordham alumni, Rose Marie Bravo, TMC ’71, former CEO of Burberry, was among the first in her family to go to college. In gratitude for her parents’ support, she established the Biagio and Anna LaPila Endowed Scholarship Fund to help other first-generation students get a Fordham education.

80. We Completed a $500 Million Campaign in March 2014

Excelsior | Ever Upward | The Campaign for Fordham was the most successful capital campaign in University history, raising $540 million thanks to the support of 60,000 alumni and friends. They helped the University create more than 220 scholarships, build residence halls for 800-plus students, raise the number of endowed chairs to 67, transform Hughes Hall into the Gabelli School of Business, and construct the new Fordham Law School.

81. The Doty Society Honors Loyalty

George E. Doty, FCRH ’38, former Wall Street financier and CEO of Goldman Sachs, made a gift to Fordham every year from 1957 until his death in 2012. In tribute to his steady generosity, Fordham created the Doty Society to recognize donors who have given to the University for 20 years or more.

82. The Cunniffes Created a Scholars Program with a $20 Million Gift

In October 2016, Maurice J. (Mo) Cunniffe, FCRH ’54, and Carolyn Dursi Cunniffe, Ph.D., GSAS ’71, already two of Fordham’s most generous alumni, made a $20 million gift to support student financial aid.

In 1921, Ruth Whitehead Whaley became the first black woman to enroll at Fordham Law School. She graduated at the top of her class in 1924 and, one year later, became one of the first black women admitted to practice law in New York.

In 1921, Ruth Whitehead Whaley became the first black woman to enroll at Fordham Law School. She graduated at the top of her class in 1924 and, one year later, became one of the first black women admitted to practice law in New York.

84. A Jewish Doctor Was the Founding Dean of the College of Pharmacy

In September 1912, Fordham established the College of Pharmacy under the leadership of Fordham Medical School alumnus Jacob Diner, M.D., who became the first Jewish dean in the University’s history. The Jesuits’ superior general was not happy about a Jewish dean, but Fordham Jesuits—most notably Joseph B. Keating, S.J.—rallied to Diner’s defense. He remained dean until 1932; the College of Pharmacy closed in 1971.

85. Fordham Had the First Female Dean of Any U.S. Jesuit University

In 1939, Fordham chose Anna E. King, Ph.D., to be dean of the School of Social Service. King became not only Fordham’s first female dean but also the first female dean at any Jesuit university in the country. In 1945, she was elected president of the American Association of Schools of Social Service. That same year, she initiated the school’s first master’s degree program. She served as dean until 1954.

In 1939, Fordham chose Anna E. King, Ph.D., to be dean of the School of Social Service. King became not only Fordham’s first female dean but also the first female dean at any Jesuit university in the country. In 1945, she was elected president of the American Association of Schools of Social Service. That same year, she initiated the school’s first master’s degree program. She served as dean until 1954.

86. Women Had Their Own Undergraduate College for 10 Years

In fall 1964, the University opened Thomas More College, an undergraduate school for women. Though women had been earning Fordham degrees in law, education, and social service for decades, the Thomas More students initiated a profound cultural shift. “It was a man’s world when we got here, but I think we quickly changed that,” Margaret Bia, M.D., TMC ’68, a member of the school’s first graduating class, recalled in 2014. The college closed in 1974, after Fordham College at Rose Hill began accepting women.

87. Coeds Came to Fordham Law in 1918

On September 22, 1918, Fordham Law School placed its usual start-of-term ad in The New York Times—with one notable exception: the phrase “courses open to women.” As the academic year began, eight women strode into the Woolworth Building (then home to the law school) and into Fordham history.

88. The First Black Woman in the Coast Guard Later Taught Psychology at Fordham

As a young girl in Oklahoma, Olivia Hooker, Ph.D., survived the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot, hiding under her kitchen table as white men burned down her affluent black community. Twenty-four years later, she became the first black woman to enlist in the U.S. Coast Guard. She taught psychology at Fordham from 1963 to 1985. In 2015, shortly before celebrating her 100th birthday, she reminisced about her time at Fordham: “Everybody helped each other and thought highly of each other and loved to be there.”

As a young girl in Oklahoma, Olivia Hooker, Ph.D., survived the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot, hiding under her kitchen table as white men burned down her affluent black community. Twenty-four years later, she became the first black woman to enlist in the U.S. Coast Guard. She taught psychology at Fordham from 1963 to 1985. In 2015, shortly before celebrating her 100th birthday, she reminisced about her time at Fordham: “Everybody helped each other and thought highly of each other and loved to be there.”

89. The Geraldine Ferraro Rose Grows on Campus

In 1984, Walter Mondale, the Democratic nominee for president, selected New York Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro, LAW ’60, as his running mate—the first time a national party nominated a woman for vice president of the United States. “There are no doors we cannot unlock,” the Fordham Law alumna said during her acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention. The ticket lost, but Ferraro helped place a new generation of women on equal—and more secure—footing with their male counterparts.

In 2007, Fordham honored her by hosting the ceremony introducing the Geraldine Ferraro rose. Sales of the hybrid tea rose funded studies and treatment of multiple myeloma, which Ferraro lived with for more than a decade before her death in 2011. The University planted the rose on the Lincoln Center campus.

90. New York City’s First Black Welfare Commissioner Was a Fordham Dean

Nicknamed “Little Dynamo” for his diminutive stature and boundless accomplishments, James R. Dumpson, Ph.D., fought fiercely for the rights of children, the poor, the infirm, and the elderly. He pushed limits and broke barriers—for others as well as for himself. In 1959, he became the first black man to serve as New York City’s welfare commissioner, and from 1967 to 1974, he was dean of Fordham’s Graduate School of Social Service, an appointment that made him the first black dean of a nonblack school of social work in the country. Dumpson died in 2012 at age 103, having dedicated his life to striving for what he called “a caring society for all Americans.”

Nicknamed “Little Dynamo” for his diminutive stature and boundless accomplishments, James R. Dumpson, Ph.D., fought fiercely for the rights of children, the poor, the infirm, and the elderly. He pushed limits and broke barriers—for others as well as for himself. In 1959, he became the first black man to serve as New York City’s welfare commissioner, and from 1967 to 1974, he was dean of Fordham’s Graduate School of Social Service, an appointment that made him the first black dean of a nonblack school of social work in the country. Dumpson died in 2012 at age 103, having dedicated his life to striving for what he called “a caring society for all Americans.”

In The Adjustment Bureau, Matt Damon plays a fictional Fordham alumnus who returns to campus to announce that he’s running for U.S. Senate. The movie, shot in part at Rose Hill in 2009, is far from Fordham’s first film credit. The University also had cameos in The Exorcist (1973), Quiz Show (1994), A Beautiful Mind (2001), and Wall Street 2: Money Never Sleeps (2010), among other films.

In The Adjustment Bureau, Matt Damon plays a fictional Fordham alumnus who returns to campus to announce that he’s running for U.S. Senate. The movie, shot in part at Rose Hill in 2009, is far from Fordham’s first film credit. The University also had cameos in The Exorcist (1973), Quiz Show (1994), A Beautiful Mind (2001), and Wall Street 2: Money Never Sleeps (2010), among other films.

92. U2 Rocked Rose Hill

Thousands of students, faculty, and staff rose before dawn on March 6, 2009, to watch U2 play a free concert on campus—a four-song set broadcast live on ABC’s Good Morning America. “We joined a rock-and-roll band so we could get out of going to college,” Bono said from the terrace of Keating Hall. “Maybe if it looked like this and felt like this, things could have been different.”

93. Good, Good, Good … Good Vibrations Shook the Gym in 1966

93. Good, Good, Good … Good Vibrations Shook the Gym in 1966

Fordham was the place to be Friday night, March 18, 1966, when the Beach Boys performed in the Rose Hill Gym—a seminal event in the University’s rock-and-roll history.

94. Poitier, Peck, and Wood Were All Directed by a 1948 Alumnus

Harper Lee once described Atticus Finch, the moral center of her classic novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, as a “man of absolute integrity with as much good will and good humor as he is just and humane.” The same might be said of Fordham alumnus Robert P. Mulligan, FCRH ’48, the Oscar-nominated director who helped Gregory Peck bring Lee’s timeless character to life on the big screen. Known as an “actor’s director,” Mulligan brought out the best in some of Hollywood’s greatest talents, including Peck, Natalie Wood, and Sidney Poitier. His films often portrayed a young protagonist’s attempt to make sense out of a morally ambiguous world.

Harper Lee once described Atticus Finch, the moral center of her classic novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, as a “man of absolute integrity with as much good will and good humor as he is just and humane.” The same might be said of Fordham alumnus Robert P. Mulligan, FCRH ’48, the Oscar-nominated director who helped Gregory Peck bring Lee’s timeless character to life on the big screen. Known as an “actor’s director,” Mulligan brought out the best in some of Hollywood’s greatest talents, including Peck, Natalie Wood, and Sidney Poitier. His films often portrayed a young protagonist’s attempt to make sense out of a morally ambiguous world.

95. Before Orange Was the New Black, She Wore Maroon

“Fordham was a huge stepping-stone in my life,” actress Taylor Schilling, FCLC ’06, told this magazine in 2011.

“Fordham was a huge stepping-stone in my life,” actress Taylor Schilling, FCLC ’06, told this magazine in 2011.

The star of the hit Netflix series Orange Is the New Black said Larry Sacharow, former director of the Fordham Theatre program, changed her life. “He had done a lot of experimental theater in the ’60s and had all of us reading this wild literature at 18 that blew everyone’s mind. I felt so safe in the program,” said Schilling, who plays Piper Chapman on the show. “It was such a gift—what Larry and the faculty did in these classes made me feel I had something to offer and I was good at what I did. As soon as you feel that spark, the sky is the limit and you’re motivated on your own. That has just never stopped.”

96. A 1922 Fordham Law Graduate Negotiated Fred Astaire’s First Movie Contract

Brooklyn native Fanny Holtzmann, a 1922 graduate of Fordham Law School’s evening division, went on to become one of the top entertainment lawyers of her day, whose clients included Louis B. Mayer and Fred Astaire. But she also was an international activist, helping Eastern European Jews immigrate to the United States during the 1930s and ’40s, and later working to secure Israel’s admission to the United Nations.

Brooklyn native Fanny Holtzmann, a 1922 graduate of Fordham Law School’s evening division, went on to become one of the top entertainment lawyers of her day, whose clients included Louis B. Mayer and Fred Astaire. But she also was an international activist, helping Eastern European Jews immigrate to the United States during the 1930s and ’40s, and later working to secure Israel’s admission to the United Nations.

97. We Have a Super Agent Among Us

Bronx native Kevin Huvane, FCRH ’80, rose from working-class roots to become one of the most powerful people in Hollywood. As a managing partner of Creative Artists Agency, his longtime clients include Meryl Streep, Julia Roberts, Jon Hamm, Melissa McCarthy, and Tom Cruise.

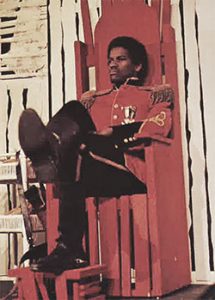

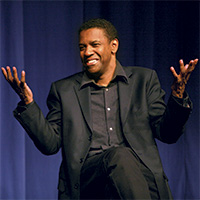

98. Denzel Found His Calling on a Fordham Stage at Lincoln Center

Two-time Academy Award winner Denzel Washington, FCLC ’77, received a lifetime achievement award at the 2016 Golden Globes last January, with Tom Hanks introducing the Fordham alumnus as one of the “immortals of the silver screen.”

But the renowned actor, who grew up near the Rose Hill campus, in Mount Vernon, New York, did not set out to become one of Hollywood’s brightest lights. As an undergraduate at Fordham College at Rose Hill during the 1970s, he played basketball and considered a career in medicine before shifting to journalism. During his junior year, however, he transferred to Fordham College at Lincoln Center, where he found his calling in the University’s theatre program.

“I bluffed my way into my first [college acting]job,” Washington told TV host Merv Griffin in 1985, eight years after earning his Fordham degree. “They were doing Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones, and I was up for the leading role in the first play I had ever done. … I got good feedback right away, which was very important, and I said, ‘Oh, this is what I’m supposed to do.’”

One of the first people at Fordham to recognize Washington’s potential was Robert Stone, Ph.D., a longtime English professor at the University who decades earlier had acted with the legendary Paul Robeson in a Broadway production of Othello. “Denzel gave the best performance of Othello I’d ever seen,” Stone told this magazine in 1990. “He has something which even Robeson didn’t have … not only beauty but love, hatred, majesty, violence.”

Washington has long been a champion of Fordham and Fordham students. He served on the University’s Board of Trustees from 1994 to 2000. And in 2011, he established an endowed faculty position, the Denzel Washington Chair in Theatre, with a $2 million gift to the University. He also contributed $250,000 to create an endowed scholarship fund for students in the Fordham Theatre program.

Washington has long been a champion of Fordham and Fordham students. He served on the University’s Board of Trustees from 1994 to 2000. And in 2011, he established an endowed faculty position, the Denzel Washington Chair in Theatre, with a $2 million gift to the University. He also contributed $250,000 to create an endowed scholarship fund for students in the Fordham Theatre program.

“My life is not typical in this profession, but one thing I know I have in common with everybody here is the ability to give back,” he told Fordham students during an October 2012 visit to campus. “Take what you have and use it for good.”

99. We Don’t Just Produce Actors, We Produce Producers

John Johnson, FCLC ’02, was a Fordham junior when he began interning with Joey Parnes Productions. That’s when he met Broadway producer Elizabeth McCann, LAW ’66, a nine-time Tony Award winner. She became a mentor to him, and now, 15 years later, he’s a producer with six Tonys to his credit. “She is a legend and has blazed so many trails for so many people,”Johnson told this magazine in 2014. “She’s like my third grandmother.”