On July 19, 2018, Bigelow was driving around his hometown of Easton, Connecticut, with two friends before heading back to school. The driver, who was intoxicated, accidentally crashed the vehicle. The driver and another passenger were mostly uninjured, but Bigelow could no longer walk on his own.

A neck fracture had paralyzed Bigelow from the chest down and limited his arm and hand movement. After the accident, he underwent emergency spinal surgery at Yale University Hospital in New Haven, where doctors tried to repair his vertebrae. He spent the next few weeks in the surgical intensive care unit, where he required a ventilator, tracheotomy, and feeding tube. Once he was stabilized, Bigelow was transferred to Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital in Boston, a facility with a special spinal cord center that could provide the care he needed.

Over the next four years, he underwent multiple surgeries, physical rehabilitation, and therapy to try to recover his mobility. His parents also moved from their Connecticut home to a wheelchair-accessible apartment in Boston, where they could better support their son.

It was a miracle that Bigelow had survived the car crash, especially without any brain injuries, said his family. But his life would never be the same.

“Before the accident, I was the most independent I had ever been. I had moved out of my childhood home, I was living on my own. Then I moved to a new state and was taken away from my friends and hometown,” said Bigelow. “Everything, from going to the bathroom to sexual function, also changed. I wasn’t able to properly feed myself, get out of bed, get dressed, or bathe.”

His final year at Fordham stretched into a three-year-long hiatus. He could no longer play club lacrosse or continue his summer job as a tram driver at the nearby New York Botanical Garden. He was also unable to graduate with his classmates in 2019.

The accident changed everything, but it also gave him a new perspective on life, he said.

“It gives you perspective on everything you once took for granted and what you used to consider difficult,” he said. “It really made me appreciate my family and the relationships I’ve built in my life.”

Returning to Fordham: ‘It Feels and Looks Like Home’

After becoming more accustomed to life with his disability, Bigelow returned to Fordham College at Rose Hill in fall of 2020. He took advantage of the online courses offered during the pandemic and learned how to complete his schoolwork alongside his disability. Instead of using a computer and keyboard to type papers, he used voice dictation on an iPad Pro. His advisers at Fordham also pitched in.

“The Office of Disability Services made test-taking, scheduling, and note-taking as simple as possible,” he said, giving a special shout-out to the office director, Mary Byrnes.

Bigelow said he was concerned that his disability would cause him to fall behind his able-bodied classmates, but he proved himself wrong.

“I was really worried that because of my injury and not feeling like I could always do everything as easily as my classmates, that I would fall behind and lose out on those honors that I was proud of,” said Bigelow, who received a Loyola Scholarship, a renewable scholarship that requires a minimum cumulative GPA of 3.00, as an incoming first-year student. “But I finished my degree and maintained at least a 3.00 GPA.”

The last time he stepped foot on campus was nearly four years ago, before his accident. On May 21, 2022, he returned to Rose Hill to receive his bachelor’s degree in economics at Commencement.

Bigelow said that his friends and family asked him if the campus looked different. “No,” said Bigelow, who had lived in Loschert Hall and off-campus apartments in the Bronx. “It feels and looks like home.”

‘I Can Do Those Things—Just in a Different Way’

Bigelow now lives in Marina Bay, a Boston neighborhood lined with restaurants and boats. He and his girlfriend live in a two-bedroom apartment with their four-month-old kitten, Batman.

In the future, he sees himself working remotely in a senior data analytics position in the banking, finance, or insurance industries. He said he wants to continue exercising regularly at his local YMCA and enjoying life in Boston, particularly the theater district.

After years of therapy, Bigelow is able to grasp objects, although he can’t hold onto them for a long time. He can brush his hair and teeth and use a stylus for his iPad Pro, which has become an essential tool in his daily life. But he still deals with chronic pain and fatigue everyday.

Bigelow said his doctors have told him that most mobility returns within two years of an injury. But instead of focusing on what he might be able to do, he said he tries to focus on what he can do.

“There’s always a way to do what you want to do. It might not be the way you expected or the way you’re accustomed to, but there’s always a way to find out how to get what you want,” Bigelow said. “When it comes down to it, I can do those things—just in a different way.”

]]>“A congregation can go through that same kind of movement of being afraid,” said Gaventa, a longtime expert in disabilities and spirituality, who spoke at the Fordham symposium “Tikkun Olam: Spirituality, Intellectual Disabilities, and Wholeness” on March 17. “What you will hear from me this afternoon are some reflections that come from years of trying to be a bridge between the world of spirituality and faith, on the one hand, and the worlds of secular and public services, private services, and advocacy on the other—trying to find ways for those two communities to talk with each other and to work together for the sake of people with disabilities and the quality of their lives.”

Spirituality can be an essential part of a person’s identity. This is the realm where people try to discover and make meaning for their lives and learn to cope with personal crises, including the diagnosis of a disability, said Gaventa.

Many people in the disabled community are spiritual, but their spiritual needs are often mishandled by the professionals who are responsible for their well-being, he said. A person’s spirituality is often viewed as a private matter, and the people surrounding them—disability service providers and faith communities, including churches, synagogues, mosques, and temples—frequently don’t know how to communicate to each other about their clients’ spiritual needs, Gaventa explained.

People with disabilities and their families want congregations to offer a welcoming and positive attitude, to create an accessible environment, and to give them opportunities to serve their community, according to research Gaventa cited from longtime expert Erik W. Carter, a professor of special education at Vanderbilt University.

In order for this to happen, there needs to be education and training for staff and parishioners, said Gaventa, who founded a summer institute that provides spiritual support for people with disabilities and their families. Perhaps most importantly, people from both parties need to listen to each other’s needs and develop authentic relationships, said Gaventa.

“At the heart of this, it’s about not programs or worship service … it’s about relationships,” Gaventa said. “How do we help people build relationships beyond the circle of relationships that they [already]have?”

People with disabilities and their congregations can teach and learn from each other, said Gaventa, including families with children who have autism.

“If somebody [with autism]has grown up in that faith community, and people have gotten to know them and got to know the person behind those behaviors and what people are trying to do both at school and at the faith community, then you can work on ways [to help them],” Gaventa said. “One, help the individual learn the kinds of things that are typical to learn and show them how to do it and provide multiple opportunities for them to practice. And on the other hand, help the community learn that [there are]some things people can change, and some things they cannot.”

One good example is the Archdiocese of Newark, which collaborated with Caldwell College to teach children with autism and other disabilities to attend Mass, Gaventa said.

“If you told me 20 years ago that we were going to marry applied behavioral analysis with CCD [religious education classes], I would have said there was no way because they don’t talk the same language,” Gaventa said. “People can begin to change.”

Gaventa recalled a story from a Methodist church in South Jersey, where a visiting clergy member asked a mother with a disruptive child with disabilities to leave.

“The mother was just heartbroken by that and really hurt. The regular pastor found out about that, and finally said to the mom, ‘Come back, come back.’ Her son started to [become disruptive]again, and the mom started to get up and leave. And the pastor said from the pulpit, ‘Stop right there—he is part of our community. We’ll figure this out.’”

The virtual symposium was co-sponsored by Fordham’s Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education and the Fordham Research Consortium on Disability. A full recording of the event will be posted here.

]]>“She was a strong advocate for students with disabilities and was persistent in getting things done right if she believed in it. Her spirited advocacy, commitment, and unyielding persistence left a strong impact on those who were her students and mentees,” wrote her colleagues at the Graduate School of Education, Chun Zhang, Ph.D., and Abigail Harris, Ph.D., in a joint statement. “She will be dearly remembered by many of her students, colleagues, and those whose lives have been touched because of her work.”

From 1989 to 2007, Ellsworth taught scores of Fordham students how to serve children with disabilities in the classroom. She recognized the importance of collaborating with school psychologists and counselors, and she encouraged research related to the assessment of learning and methods for teaching literacy, said her colleagues.

Ellsworth advocated for individuals with special needs at home and abroad. In New York, she worked closely with the state education department and national professional organizations to earn accreditation for special education programs; on a citywide level, she worked to improve bilingual public school education by expanding training for special education teachers. She also worked with special education teachers in China and co-authored a 2007 journal article that examines the country’s development of the special education field.

“I remember Dr. Nancy Ellsworth as an insightful and stabilizing influence during a time of significant transition … in the special education field,” her colleague John Houtz, Ph.D., professor of educational psychology at Fordham, wrote in an email. He noted that her expertise had an impact at a time when the special ed field was in need of new programs and facing new state accreditation standards. “Her years at GSE were marked by hard work and significant problem solving. She was a favorite of students and a model and mentor to our next generation of faculty.”

Ellsworth was born in August 1932 in San Marino, California, to Larry and Jane Hood. She graduated from Stanford University with a bachelor’s degree in political science and a master’s degree in education, with a focus on English and social studies.

She began working at the World Affairs Council, a San Francisco-based nonprofit, and went on to teach middle and high school students in the Bay Area, where she realized her lifelong passion as an educator. In 1969, she married Robert T. Ellsworth, Jr., and moved to Bedford, New York. The couple enjoyed camping, whitewater paddling, and the performing arts together.

Over the next two decades, she earned a master’s degree in education, specializing in reading and learning disabilities, and a doctorate in education, with a focus on special education, both from Columbia University.

In 2005, Ellsworth returned to her native California to live closer to her family. As a retiree, she was an active member of her local bridge, book, and film groups. In her final months, she spent most of her time with her family. Her daughter, Susan Flierl, recalled making morning coffee and breakfast for her mother and watching The Queen’s Gambit and The Crown together, often with the family dog, Cooper, lying at her mother’s side.

“Nancy was blessed with a full, active, and independent life through her 88th birthday,” Flierl wrote in an email. “Although last year was challenging due to the pandemic, the silver lining was that we had more time than ever together. We formed a social bubble, and she came over for dinner most evenings. For her birthday, I drove with her out to the California coast that she loved.”

Predeceased by her husband, Robert in 1998, Ellsworth is survived by her children, Carol Ellsworth and Alex Sturgeon (Princess) of Kansas City, Missouri; Susan Flierl (Markus) of Ladera, California; stepdaughters, Linda Ellsworth of Tempe, Arizona, and Nancy Swenson (Larry) of Heath, Texas; and two grandchildren, Andreas and Sofia Flierl.

Ellsworth’s family is hosting a virtual event to commemorate her life on Saturday, March 20 at 2 p.m. EST. Members of the Fordham community can reach out to [email protected] if they are interested in attending.

]]>“Disabilities are often perceived as a small minority issue—something that affects a mere 1%. That’s not the case,” said Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., co-director of the minor program, founding director of the Research Consortium on Disability, and professor of economics.”

Around one billion people worldwide live with a disability, according to the United Nations, including one in four adults in the U.S. alone, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since the minor started in January 2019, students in the program have learned how disability and normality are understood and represented in different contexts, from literature to architecture to fashion. The curriculum also helps bring awareness to issues of access on Fordham’s campus and beyond.

“Our minor program gets students to think about what it means to have a disability and what the consequences of having a disability might be in society,” Mitra said. “It’s an essential part of thinking about inclusion and what it means to be an inclusive society—and yet, it’s a dimension of inclusion that we sometimes forget about.”

The program is designed to show undergraduates how to create more accessible physical and social environments and help them pursue careers in a range of fields, including human rights, medicine and allied health, psychology, public policy, education, social work, and law.

Among these students is Sophia Pirozzi, an English major and disability studies minor at Fordham College at Rose Hill.

“The biggest thing that I’ve taken away is that when minority rights are compromised, so are the majority … And I think when we elevate that voice and that experience, we come a little bit closer to taking into consideration that the only way to help ourselves is to help other people,” said Pirozzi, who has supervised teenagers with intellectual and physical disabilities as head counselor at a summer camp in Rockville, Maryland. After she graduates from Fordham in 2021, she said she wants to become a writer who helps build access for the disability community.

Now, in addition to the minor program, Fordham has a Research Consortium on Disability, a growing team of faculty and graduate students across six schools—the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the Graduate School of Education, the Graduate School of Social Service, the Gabelli School of Business, the Law School, and the Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education—who conduct and coordinate disability-related research at at the University.

Since this past October, the consortium has created new opportunities to connect faculty and graduate students working on disability-related research across the University and in the broader New York City area, including lunch meetings and new research studies. This month, it launched its new website. The consortium is planning its first symposium on social policy this November and another symposium on disability and spirituality in April 2021.

The consortium is a “central portal” for interdisciplinary research that can help scholars beyond Fordham, said Falguni Sen, Ph.D., professor and area chair in strategy and statistics, who co-directs the consortium with Rebecca Sanchez, Ph.D., an associate professor in English. That includes research on how accessible New York City hospitals are for people with disabilities, particularly in the COVID-19 pandemic.

“What has come to light very acutely is the whole notion of how vulnerable populations have been differentially affected in this COVID-19 [pandemic],” Sen said. “The emergency responses to that population have not necessarily been as sensitive or as broad in terms of access as we would like it to be … And we were already thinking about issues of crisis because of what happened in 9/11.”

The minor and the Research Consortium on Disability build upon the work of the Faculty Working Group on Disability: a university-wide interdisciplinary faculty group that has organized activities and initiatives around disability on campus over the past five years. The group has hosted the annual Fordham Distinguished Lecture on Disability and several events, including a 2017 talk by the commissioner for the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities.

“Fordham is known for community-engaged learning and how its work, both the research that we do and others, have relevance directly in people’s lives,” said Sen. “And that’s what we are trying to do.”

]]>Anne Fernald, Ph.D., acting associate dean of the arts and sciences and professor of English and women’s studies, organized the Jan. 11 event to help Fordham faculty better address the curricular and instructional needs of students with disabilities such as hearing loss, blindness, learning disabilities, and psychological disorders.

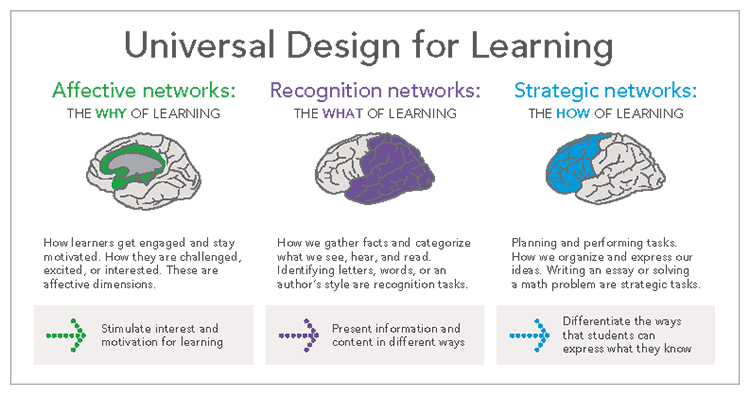

“There is a lot that professors can learn from their students,” said Fernald, who believes that universal design learning techniques can transform pedagogy for today’s students.

“The goal is to help professors feel excited and comfortable about all of the different abilities and experiences that exist in their classrooms.”

Among the workshop’s attendees was Rafael Zapata, Fordham’s first chief diversity officer.

“There are so many ways that we can signal to students that who they are matters to us,” he said.

“As a community, we want to be supportive of them as much as possible to help them realize their potential.”

Creating an Access Statement

Rebecca Sanchez, Ph.D., an associate professor of English whose research focuses on transatlantic modernism, disability studies, and poetics, said one of the first steps educators can take to show students that they are invested in their success is to include an access statement in their syllabi.

The statement generally notes that there are different ways to access class materials, take exams, and participate in classroom activities.

“By creating your own access statement, you’re suggesting to disabled students that their arrival in your class does not constitute some kind of crisis for you, or is the first time you’ve thought about disability,” she said.

Showcasing Diverse Representations

Using an excerpt from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2009 TED talk about the dangers of a single story, Alessia Valfredini, Ph.D., professor of modern language and literatures, encouraged attendees to be proactive and intentional about representations of ability and disability in their coursework. Whenever possible, coursework should showcase a variety of human experiences and perspectives.

“Our courses are a reflection of the world as we see it,” said Valfredini, who contributed via a transcribed video. “By presenting a certain type of class, we make a statement about who the legitimate actors in the work are.”

Using Technology

Lindsay Karp, a senior instructional technologist at the Lincoln Center campus, presented examples of how technology can take pedagogy to the next level. Her suggestions included making file names descriptive and specific, condensing URLs, using fonts and font sizes that are easier to read, and incorporating a table of contents in long text. She also suggested using subtitles and captions.

“Captions are not just fantastic for [students] who are hard of hearing, but also for foreign students who are learning the language,” she said.

Reinforcing Learning

Carla Romney, Ph.D., associate dean for STEM and pre-health education at Fordham College at Rose Hill, argued for presenting materials in multiple modes.

She makes her lectures available in a video format and uses YouTube to create closed captioning. Students then take turns editing the captions.

“Making [students] listen to the lessons twice and having them transcribe it is another means of reinforcing their learning,” she said.

Providing Options

Whether it be offering structured assignments or giving students an open-ended project, providing students with different variations of assignments may spark creativity and inspire them to take ownership of their work.

“Not everyone is interested in knowledge in the same way,” said Orit Avishai, Ph.D., assistant professor of anthropology. “People learn differently and have different kinds of preferences.”

Prioritizing Community Building

Creating opportunities for group work and community building can be especially transformative.

“Very often the people who are doing the work of supporting our students are other students in [our] courses,” said Badr Albanna, Ph.D., assistant professor of neurophysics.

“The more work you can do to make that possible, accessible, and easy for students to do, that can have a tremendous impact on all students, and particularly for students whose needs you may not be aware of.”

]]>At Fordham, the celebration began a day early with an interdisciplinary symposium spotlighting faculty and students research focused on disability. The Dec. 2 event, “Diversity and Disability: A Celebration of Disability Scholarship at Fordham,” also marked the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Matthew Diller, dean of Fordham School of Law and the Paul Fuller Professor of Law, discussed how disability law influences people’s participation in the workforce. This participation, Diller said, is socially as well as economically important, because work signifies social status.

“Work is central to how we think about people, their role in society, and whether they are successful members of that society,” Diller said. “There is a social expectation that you should be in the workforce, and if you’re not, then you’re an underperforming member.”

Not everyone can fulfill that expectation, Diller said, so the law allows for some people to be excused from work owing to certain situations or conditions, such as a disability. Some people, however—including people with disabilities—are excluded from work altogether as the result of prejudice, discrimination, or other barriers that prevent them from fully participating in society.

“If we judge social worth by whether someone works, but then exclude some people from the workforce, then we’re inherently denigrating their social worth,” he said.

The value of the ADA, Diller said, is that it focuses on creating systems that integrate people with disabilities into the workforce, thereby restoring their right to work.

However, there remains room for improvement, Diller said. For instance, up until Congress substantially amended the law in 2008, courts regularly impeded the ADA’s enforcement by making the definition of disability extremely narrow. Many plaintiffs seeking excusal from or accommodations for work lost their cases on the grounds they were not disabled—an approach Diller said was “misguided.”

Photo by Dana Maxson

Christine Fountain, PhD, assistant professor of sociology, and Rebecca Sanchez, PhD, assistant professor of English, also presented.

Fountain is doing research with scientists from Columbia University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the sociological aspects of autism, particularly how a noncontagious illness has reached epidemic proportions and who is being most severely affected by it.

Autism, the group has found, is more prevalent in children of wealthy and well-educated parents, and that wealth and education play a role in how quickly and to what extent an autistic child improves developmentally.

Sanchez discussed her new book Deafening Modernism: Embodied Language and Visual Poetics in American Literature (New York University Press, 2015), which argues that “deaf insight,” that is, the “embodied and cultural knowledge of deaf people,” is not an impairment, but an alternative way of thinking and communicating.

She offered the example of Charlie Chaplin’s 1936 silent film Modern Times. Chaplin, Sanchez said, deliberately chose to avoid the new “talkie” technology because silent pictures allowed for “a universal means of expression.” The plot of the film itself, she said, bespeaks the dangers of forcing people to express themselves in homogenized ways.

The event also included poster presentations by two doctoral students, Xiaoming Liu and Rachel Podd, and Navena Chaitoo, FCRH ’13.

Photo by Dana Maxson

Elizabeth Emens, PhD, the Isidor and Seville Sulzbacher Professor of Law at Columbia Law School, offered the keynote presentation, “Disability Law Futures: Moving Beyond Compliance.”

The event was sponsored by the Office of Research and by the Faculty Working Group on Disability, led by Sophie Mitra, PhD, associate professor of economics. The group connects Fordham faculty who are researching some aspect of disability.

]]>