“His mother’s love opened him up again … and gave his life meaning, purpose, and hope, which I think is probably the best task that churches can do for anybody who lives with a highly stigmatized condition—to offer love and friendship,” said Swinton, in an online lecture on April 8.

Swinton, the chair of divinity and religious studies and professor of practical theology and pastoral care at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, was the keynote speaker at Fordham’s Spirituality & Disability Symposium, which took place on April 8 and 9. The forum featured scholars who discussed how spirituality and disability intersect in our daily lives.

Swinton’s research and teaching are largely inspired by his eclectic background in health care and religion. For 16 years, he worked as a nurse for people with mental health challenges and learning disabilities; he also worked as a hospital chaplain. He currently serves as an ordained minister of the Church of Scotland.

In his presentation “Spirituality and Disability: What Do We Mean and Why Does It Matter?” Swinton explained how society can use spirituality as a lens for a better life, especially people who live with disabilities.

A Reimagined Jesus With Down Syndrome

Everyone has their own idea of what God looks like. Our imagination is deeply influenced by the culture in which we live, Swinton said, citing the work of theologian Karl Barth. He showed the audience a modern version of the Last Supper painting, where Jesus and his disciples all have Down syndrome. It’s a powerful image because it reminds us that both God and our society are diverse, he said.

“Paul talks about the body of Christ … the place where we see, feel, live out that image. And the thing that marks the body of Christ is not homogeneity, but diversity … And so when we recognize all the different aspects of the image of God as it’s revealed in all of the different bodily and psychological conditions that we go through, we begin to understand what it means to be in God’s image,” said Swinton. “It’s together that we live in the image of God.”

Finding Strength in Meaning and Connection

Another important aspect of spirituality is our need for connection, Swinton said. Humans evolved to become spiritual beings because of their deep desire to relate to something beyond themselves, he said, citing a theory from David Hay, a zoologist who wrote a book about spirituality.

“The one thread that runs through all definitions of spirituality is this idea of relationality—that somehow we need to be in a relationship,” Swinton said. “Spirituality has to do with being in a relationship. Maybe with God … with others … with your community, but it’s always there.”

However, people with disabilities are often shunned by society, he said.

“The problem is that we have a pathogenic culture—an individual culture that tends to stigmatize and alienate people who are different,” Swinton said. “Stigma is a deeply spiritual problem. It shrinks your world, takes away the possibilities. And unless somebody can rescue you, that can be your life—stuck in that meaningless place, where your diagnosis takes away everything.”

Swinton said that excluding people with disabilities is the opposite of what God calls us to do—“to respect diversity, to recognize the image of God in each one of us, and to come together.”

“We need to shift and change and take spirituality seriously if we’re going to have the kind of community where each one of us has a space, place, and voice,” Swinton said.

A Q&A session following Swinton’s presentation was moderated by Francis X. McAloon, S.J., Ph.D., associate professor of Christian spirituality and Ignatian studies at the Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education. The symposium was co-sponsored by GRE and Fordham’s Research Consortium on Disability.

]]>“It still gives me chills to think about what a moment that was. It was … taking ownership of this term, rather than it being used to demean or marginalize her, that gave people a framework to understand her. And so she shifted from being somebody that was enigmatic or strange to somebody who was a person with autism who wasn’t ashamed of having autism,” he said on April 4 in an online lecture.

Grinker, an award-winning professor of anthropology and international affairs at George Washington University and an expert on autism and mental illness, was the main speaker at the 2021/2022 Fordham Distinguished Lecture on Disability. His book Unstrange Minds: Remapping the World of Autism (Basic Books, 2008), inspired by Isabel, won the 2008 National Alliance on Mental Illness KEN award.

In his speech, he shared the most critical findings from his newest book, Nobody’s Normal: How Culture Created the Stigma of Mental Illness (W.W. Norton, 2021). He argues that the main cause of stigmatization against those with mental illnesses and disabilities is something that we don’t often consider—the social, cultural, and historical contexts in which we live.

‘The Ideal Person’: How American Society Became Divided

Over the past two decades, disabilities have been increasingly embraced as part of being human, rather than something shameful and frightening, said Grinker. He said he witnessed this transformation in Isabel, who is now 30, as well as his students. On the first day of class in front of nearly 300 peers, a student announced that he had Tourette syndrome, Grinker recalled, because he wanted his peers to understand the reason behind his unusual behavior.

Grinker said that society is becoming less judgmental. Increasing education and public awareness have contributed to this, he said, but what primarily shapes our stigmas against those who are “different” are the social, cultural, and historical contexts in which we live.

Capitalism, for example, created conditions that led to stigmatization. The ideal American possessed two traits that were central to capitalism: independence and autonomy. Those who lacked those traits—or were unable to possess them—were viewed as “abnormal,” he said.

“Our judgments about mental illnesses come from our definitions of what, at different times and places, people consider the ideal society—the ideal person,” Grinker said, adding that we are now moving away from the definition of an ideal person as defined by capitalism.

He also drew attention to a phenomenon that helped to destigmatize mental illness and disabilities: war.

During World War II, an unprecedented number of people suffered from mental illness. In response, U.S. President Harry Truman established the National Institute of Mental Health and ordered the military to create a manual used for the diagnosis of mental disorders.

To Be Normal Is To Be ‘Boring’

Many people aspire to be “normal,” but this mindset is actually a damaging illusion, said Grinker. He recalled a 1951 research study conducted by his father and grandfather, who were both psychiatrists. They studied a group of men who they divided into two groups: those who screened positive for mental illness and those who were “normal.” They found that the latter lacked ambition and creativity. As Grinker put it, they were “boring.”

“What my grandfather and my father were suggesting was that normality was crippling—that some degree of mental illness, some degree of mental difference might be necessary for humanity to remain vibrant, creative, and diverse,” Grinker said.

Humanity’s stigmas can never be completely eradicated—but that doesn’t mean we can’t resist them, he said.

“We only need to look at the kinds of examples that I gave you earlier, whether it’s my daughter, Isabel, or my students, to give us hope,” Grinker said.

The sixth Fordham Distinguished Lecture on Disability was co-organized by the Disability Studies Program and the Research Consortium on Disability and co-sponsored by the Conference of Arts & Science Deans and the Office of Research. The Q&A following the lecture was co-moderated by Sarah Macy, FCLC ’22, a psychology major and disability studies minor who identifies as an autistic woman, and Micki McGee, Ph.D., associate professor of sociology at Fordham and the parent of a neurologically divergent young adult.

Watch a full recording of the lecture below:

]]>“She was a strong advocate for students with disabilities and was persistent in getting things done right if she believed in it. Her spirited advocacy, commitment, and unyielding persistence left a strong impact on those who were her students and mentees,” wrote her colleagues at the Graduate School of Education, Chun Zhang, Ph.D., and Abigail Harris, Ph.D., in a joint statement. “She will be dearly remembered by many of her students, colleagues, and those whose lives have been touched because of her work.”

From 1989 to 2007, Ellsworth taught scores of Fordham students how to serve children with disabilities in the classroom. She recognized the importance of collaborating with school psychologists and counselors, and she encouraged research related to the assessment of learning and methods for teaching literacy, said her colleagues.

Ellsworth advocated for individuals with special needs at home and abroad. In New York, she worked closely with the state education department and national professional organizations to earn accreditation for special education programs; on a citywide level, she worked to improve bilingual public school education by expanding training for special education teachers. She also worked with special education teachers in China and co-authored a 2007 journal article that examines the country’s development of the special education field.

“I remember Dr. Nancy Ellsworth as an insightful and stabilizing influence during a time of significant transition … in the special education field,” her colleague John Houtz, Ph.D., professor of educational psychology at Fordham, wrote in an email. He noted that her expertise had an impact at a time when the special ed field was in need of new programs and facing new state accreditation standards. “Her years at GSE were marked by hard work and significant problem solving. She was a favorite of students and a model and mentor to our next generation of faculty.”

Ellsworth was born in August 1932 in San Marino, California, to Larry and Jane Hood. She graduated from Stanford University with a bachelor’s degree in political science and a master’s degree in education, with a focus on English and social studies.

She began working at the World Affairs Council, a San Francisco-based nonprofit, and went on to teach middle and high school students in the Bay Area, where she realized her lifelong passion as an educator. In 1969, she married Robert T. Ellsworth, Jr., and moved to Bedford, New York. The couple enjoyed camping, whitewater paddling, and the performing arts together.

Over the next two decades, she earned a master’s degree in education, specializing in reading and learning disabilities, and a doctorate in education, with a focus on special education, both from Columbia University.

In 2005, Ellsworth returned to her native California to live closer to her family. As a retiree, she was an active member of her local bridge, book, and film groups. In her final months, she spent most of her time with her family. Her daughter, Susan Flierl, recalled making morning coffee and breakfast for her mother and watching The Queen’s Gambit and The Crown together, often with the family dog, Cooper, lying at her mother’s side.

“Nancy was blessed with a full, active, and independent life through her 88th birthday,” Flierl wrote in an email. “Although last year was challenging due to the pandemic, the silver lining was that we had more time than ever together. We formed a social bubble, and she came over for dinner most evenings. For her birthday, I drove with her out to the California coast that she loved.”

Predeceased by her husband, Robert in 1998, Ellsworth is survived by her children, Carol Ellsworth and Alex Sturgeon (Princess) of Kansas City, Missouri; Susan Flierl (Markus) of Ladera, California; stepdaughters, Linda Ellsworth of Tempe, Arizona, and Nancy Swenson (Larry) of Heath, Texas; and two grandchildren, Andreas and Sofia Flierl.

Ellsworth’s family is hosting a virtual event to commemorate her life on Saturday, March 20 at 2 p.m. EST. Members of the Fordham community can reach out to [email protected] if they are interested in attending.

]]>“We wanted to get into quality education, the ability to move around the city in our communities, the ability to get jobs, get paid, live in the community, get married, have children. And I think … we realized we could make a difference if we did it ourselves.”

These words come from Judith “Judy” Heumann, a 72-year-old pioneer of the disability rights movement recently featured in TIME’s list of the most influential women of the past century. Heumann reflected on her life of activism at Fordham’s fifth annual Distinguished Lecture on Disability, “The Disability Rights Movement: Where We’ve Been, Where We Are, and Where We Need to Go,” in a Zoom webinar on Oct. 14.

A Five-Year-Old ‘Fire Hazard’ Girl

Heumann became New York City public schools’ first teacher in a wheelchair after winning a landmark court case. She helped spearhead the passage and implementation of federal civil rights legislation for disabled people, including the Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504, a federal law that prevents discrimination against individuals with disabilities. She also served in various leadership roles, including the World Bank’s first adviser on disability and development and the first special adviser for international disability rights under the Obama administration. In recent years, she has been working to change the portrayals of disabled people in the media as a senior fellow for the Ford Foundation.

At the beginning of the webinar, she recalled that when she was a five-year-old girl with polio, the principal of a local school told her she couldn’t attend classes because she was a “fire hazard.”

“As I was getting older and meeting other disabled people, in my special ed classes and then at camp, it was becoming very apparent that we were facing discrimination without any real group of people speaking up against discrimination,” said Heumann, who had joined students earlier that day for a Q&A about the recent film Crip Camp, which featured the stories of disabled teens—including Heumann—at camp in the 1970s and their role in igniting the disabilities civil rights movement.

In that same period, she said, she also saw scores of people on TV standing up for civil and women’s rights across the country. They inspired her to lead demonstrations, start new organizations, and use legislation to fight discrimination directed toward the disability community, all while working closely with the community, religious leaders, and labor unions.

“All [these]types of activities were what enabled congressional representatives and U.S. senators to understand that the discrimination that disabled people were facing was not something that happened once in a while,” Heumann said. “It happened in every community, in every state—and it happened regularly.”

Ongoing Obstacles for the Disability Community

In the wake of much progress, the disability community continues to struggle, said Heumann. Many Americans don’t realize they have a disability protected by law; others face stigmas and repercussions related to their disability, she said. There is a disproportionate number of disabled individuals in juvenile and adult facilities—people who may not have ended up in prison if they’d received “appropriate services along the way.” There isn’t enough money being dedicated to education for both nondisabled children and disabled children on local, state, and countrywide levels, she said, and many teachers-in-training at colleges and universities are not taught how to teach students in inclusive settings.

Toward the end of the evening, the moderator of the event, Navena Chaitoo, FCRH ’13, a research manager at New York City mayor’s office of criminal justice, asked Heumann how people could take specific steps to help the disability community.

“We’re talking about stronger parent training programs. We’re talking about better programs in universities for teachers, principals, and superintendents,” Heumann said. “We’re talking about our local school boards. Who are the people that you’re electing? … Are they fighting for you and your kids with disabilities?”

“It all gets, to me, back to voting and knowing the people who are running for office and being more demanding and working collaboratively together.”

‘We Need to Normalize This’

In a Q&A, an audience member asked Heumann how society could lower stigmas around “invisible disabilities” like mental illness.

“You look at Covid right now, and we’re talking about people having increased anxiety, increased depression, other mental health disabilities, and our inability to speak about this is both harmful to the individual person, to the family, and to the community at large. And so I think like with each category of disabled people, we need to normalize this,” Heumann said. She added that that specific movement needs to be led by people who have psychosocial disabilities themselves, like Andrew Imparato, executive director at Disability Rights California, who has openly spoken about his experience with bipolar disorder. She emphasized that we need to listen to people’s experiences and try our best to understand them. Lastly, she noted the importance of advocacy across generations and for youths, including students, to stand up for themselves.

“Most importantly is allowing people the space and giving people the protections that they need,” Heumann said. “We have 61 million disabled people in the United States. If 5 million of us on a regular basis were speaking up and speaking out, it would have an amazing impact.”

The live Zoom lecture, which featured two American Sign Language interpreters and live captioning, comes under two key initiatives on disability at Fordham: the disability studies minor and the research consortium on disability. The event was organized by the Faculty Working Group on Disability and co-sponsored by the offices of the provost and chief diversity officer, the Graduate School of Education, the School of Law, the Gabelli School of Business, the Graduate School of Social Service, and the departments of economics and English.

Watch the full webinar in the video below:

]]>Unfortunately, the numbers don’t necessarily affect elections in the way one might expect, said Faye Ginsburg, Ph.D. and Rayna Rapp, Ph.D., professors of anthropology at New York University and founders of the Council for the Study of Disability. The two took turns reading from prepared remarks, while a transcript of the lecture flashed across a screen, and an interpreter provided a translations in American Sign Language.

The researchers made their remarks at the Fordham Distinguished Lecture on Disabilities, delivered on April 27 at the Rose Hill campus. The lecture, “Disability Publics: Toward a History of Possible Futures,” examined how the presence of disabilities is dramatically increasing and transforming national consciousness. It was initially thought that growing numbers might wake a “sleeping giant,” during the 2016 presidential campaign.

“Given the stark contrast between the Clinton and Trump campaigns around disability issues, we nonetheless assumed . . . that the disability vote would indeed rally for Clinton, whose policy recommendations addressed areas of key importance to this constituency,” they said.

The speakers said they had been optimistic because of the increased visibility of the community through social media, including a campaign called “#cripthevote” which rallied the disability vote.

Candidate Trump’s mocking of New York Times reporter Serge Kovaleski, who has arthrogryposis, seemed to shore up the disabilities vote for Clinton, they said. And the Clinton campaign capitalized on the gaffe by running an ad in which a teen age cancer survivor with a limp watches footage from the rally and tells viewers: “I don’t want a president who makes fun of me, I want a president who inspires me.”

A month later disability activist Anastasia Somoza was a featured speaker at the Democratic National Convention. Ginsburg and Rapp said the infrastructure of the convention was notable for its attention to accessibility.

“For a brief moment, it seemed as if political arithmetic might work to alter the electoral process,” they said.

However, the two said they were stunned when Trump won the electoral vote. “We had to revisit our overly optimistic assumptions about a unified disability constituency and scrutinize what actually happened.”

It turned out that the disability vote was split along party lines, as it had always been—despite Trump’s egregious behavior, they said.

The speakers said they’re profoundly concerned about enforcement of the Americans with Disabilities Act, particularly after Secretary of Education Betsy deVos’s confirmation hearing revealed a lack of knowledge of the legal entitlements to special education.

While Attorney General Jeff Sessions is more knowledgeable, they said, he has shown “contempt” for the legal guarantees for free and appropriate public education of American children with disabilities. They said it’s time to make the political platforms on disability rights more transparent, so that the entire voting block understands what’s at stake.

“Clearly, we cannot take longstanding federal legislation for granted; the ADA is under threat as is the very recognition of the personhood of those with disabilities,” they said. “As scholars and activists, we need to understand what happened, as we collectively imagine how we might move forward.”

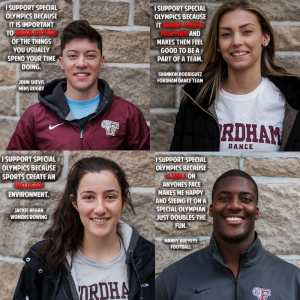

]]>A year later, Biggins co-founded the Special Olympics Club at Fordham to help create welcoming and supportive environments for adults and children with disabilities.

“The goal of our organization is to raise awareness of Special Olympics and the special needs community, and to find ways to bring Fordham students and Special Olympic athletes [in New York]together,” said Biggins, who currently serves as the club’s president. “Our third goal is to form a beautiful community on campus that embraces inclusion, acceptance, and welcomes all people.”

On April 8, more than 30 Fordham students and Special Olympics Club members joined Camp Acorn, an Allendale-based nonprofit serving individuals with special needs, on a day trip to the Bronx Zoo. Each club member helped the campers to navigate the different exhibitions at the zoo.

“It was really amazing,” said Fordham College at Rose Hill sophomore Jeannine Ederer, vice president and coordinator of the Special Olympics Club. “They told us that they had never gone through as much of the zoo as they did with us, so that was a big accomplishment on both ends.”

Ederer said Fordham students were able to bond with individuals from the special needs community through the event.

“You don’t always have the opportunity to connect with people with disabilities on a personal level and understand what they’re capable of,” she said. “Being paired one-on-one with the campers for an entire day allowed us to learn so many things about them.”

Raising awareness

To promote its mission, the club hosted several events on campus during their Spirit Week, which ran from February 26 through March 3. That week the club held its Second Annual Red Out Fashion Show, which gave Fordham students and Special Olympians an opportunity to hit the catwalk together.

According to Gabelli School sophomore Morgan Menzzasalma, the club’s treasurer, Special Olympics athletes are often left out of many traditional extracurricular activities that are offered at schools. The club’s fashion show was an opportunity to have an event focused solely on them, she said.

“It was great to see the smiles on the children’s faces during the show,” said Menzzasalma, a track and field athlete at Fordham. “At first they started out timid, but by the end of the show, we couldn’t get them off the stage!”

The fashion show featured a live performance from American Idol contestant Brielle Von Hugel, and several raffle donations. The items included customized Fordham keepsakes from Tiffany’s, which were provided by the Office of the President; an autographed baseball from the Boston Red Sox’s Xander Bogaerts; an autographed hockey puck from the New York Rangers’ J.T. Miller; and VIP tickets for The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon and LIVE with Kelly. According to Biggins, the fashion show raised over $2,000 in support of Special Olympics New York City.

Advocating for change

Since the club launched in 2015, its members have worked to create events and initiatives that shed light on the challenges that individuals with disabilities face, many of which go beyond physical and intellectual limitations, they said.

Biggins said hearing the word “retard,” in particular, has harmful effects on the self-esteem of individuals in the special needs community. Through their “Why We Pledge” campaign, which coincided with the National Spread the Word to End the Word Pledge Day, the Special Olympics Club sought to inspire students to eliminate the R-word from their own vocabulary, and to encourage their peers to do the same.

“Social awareness is everyone’s responsibility, even if it just a small act of kindness each day,” said men’s soccer team player Christopher Bazzini, a Gabelli School junior who has been working with the special needs community for more than four years. “You don’t have to start a massive movement to help others; it could be something as simple as pledging to stop using the R-word.”

Club members said they hope students across the University would not only join them in raising awareness, but also in taking action.

“Students can often get caught up in their daily school activities, but this club has allowed me to keep others who are less fortunate than me in mind,” said Menzzasalma. “From this experience, I have gained great friends and have learned that, even as a college student, I can make a significant impact in bringing joy to another [person’s] life.”

]]>The commissioner made the remarks on March 28 at a talk sponsored by Fordham’s United Student Government and the Faculty Working Group on Disability. He said that when conversations turn to diversity, people with disabilities are often left out of the discussion because attention typically focuses on the voices of other minority groups, including black, white, Muslim, Asian, LGBTQ, and women’s groups.

People with disabilities make up 11.5 percent of New York City’s population, he said. His office works to unify the voices of those with disabilities—people using wheelchairs, the deaf and hard of hearing, those with learning disabilities—in order to make “New York City the most accessible city in the world.”

“We work in our individualized zones, but we have to find a way to band together,” Calise said.

Calise said that many of those who fought for disability rights are growing older, and the next generation grew up with the benefits of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This new generation, Calise said, needs to be more engaged.

Covering the Cost of Civil Rights

To encourage their involvement, MOPD has set up a youth council, but advocacy work remains, Calise said. Unlike other civil rights movements, disabilities measures can be harder to fight for because they can come with costs: Building a ramp, providing an interpreter for a meeting, or including assistive technology are just some examples.

“That price tag is another obstacle to overcome,” he said, noting that making that cost just another part of what the city does is the key ingredient.

MOPD focuses on four primary areas: transportation, employment, education, and access to city government.

In transportation, Calise said that of the more than 400 subway stations operating in New York City, about 100 of the stations will be wheelchair-accessible by 2020. To fill in the transportation gaps, the city and state has relied on an Access-A-Ride system since 1979. It costs taxpayers an average of $65 per ride. If the decision had been made to make the subways accessible back then, the renovations would have paid for themselves because less money would have been spent on Access-A-Ride, and the overall system would be “a lot cheaper and efficient,” he said.

The city is installing a ‘wayfinding’ system, Accessible Pedestrian Signals, that assists people who are blind or have low vision to navigate crosswalks through beep tones and vibration, he said. Due to the high expense, the office is researching ways that it could consist of a less expensive technology alternative, using GPS, Bluetooth, and beacons.

An advocate for public-private partnerships on accessibility projects, Calise said his office is working with the Department of City Planning to incentivize developers to create accessible subway entrances.

Tapping an Underutilized Talent Pool

But it’s the area of employment, Calise said, that concerns him most. With a workforce more than four million strong in New York City, only 4 percent of persons with disabilities are employed.

“It’s a poverty issue when we look at it,” he said.

And it’s not for lack of talent, he said. There are 9,000 students with disabilities in the City University of New York’s institutions. But while education may prepare these students for careers, the transition to the workforce is often a scary proposition.

“They’re afraid to leave the system,” he said. “It’s a real barrier to employment.”

Calise, who is paralyzed from the waist down from a spinal cord injury, said he knows firsthand that one of the biggest fears of going to work is losing benefits that help cover the costs often associated with medical care a person with disabilities needs.

“I was so scared to make money . . . afraid I’d lose all my benefits,” he said. “They included my doctors, my medical equipment, plus the mere $700 a month I was getting from Social Security. [But] that was my safety net.”

Making the Transition

MOPD is working to expand employment and career opportunities through its NYC: ATWORK program, made possible through the support of the city, State AccessVR, and private foundations, including the Poses Family Foundation, Kessler Foundation, and ICDNYC.

He said the Department of Education is working to set up “transition centers” in each borough to help students and families dispel the myths about transitioning to college and the workplace.

“Once we’re able to get people around the city in a more efficient way, get them through the education system, get them employment, and get them access to the government, then we’ll start to see the beginnings of true equality.”

]]>

Photo by Angie Chen

In the face of many disparate initiatives, ultimately it falls upon the central government to develop policy and monitor the activities of NGOs, said Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Economics and Fordham’s Center for International Policy Studies.

“The earthquake led to injuries and trauma, leading to more physical and mental disabilities,” said Mitra.

In an attempt to address the needs of the disabled, Gerald Oriol, Jr. was appointed Haiti’s secretary of state for the integration of persons with disabilities in 2011. Oriol, who has a disability, promptly set about redefining perceptions and collecting new data on disability via the country’s official census, set to take place later this year.

The secretary has tapped Mitra, a specialist in the economics of disability, to help hone the census questionnaire and advise on policy.

Mitra has advised that language thus far drafted in the census, which before framed disabilities as “impairments,” to be recast as “limitations on functionings.”

She has been involved in the drafting of new questions based on research from the Washington Group on Disability Statistics. A question like “Do you have difficulty seeing, even if wearing glasses?” could be answered with, “No – no difficulty,” “Yes – some difficulty,” “Yes – a lot of difficulty,” or “Cannot do at all.” The more nuanced a survey is, she said, the greater assurance that more than just the extreme cases make it into the record.

Mitra said that disability biases are not limited to Haiti.

“Whether in high- or low-income countries, negative attitudes with respect to what people with disabilities can do are still common. But in high income countries, progress has been made on the physical aspects of integration,” she said.

While cities like New York have highly visible accommodations for persons with disabilities, developing countries have more limited resources to adapt their infrastructure.

“There are the physical aspects of integration and accessibility, but then there are the social attitudes that act as barriers,” said Mitra. “Fighting the biases will affect people’s likelihood of being successful. It needs to be about physical access and social access.”

Mitra’s Haiti experiences will find their way back into Fordham’s classrooms.

“My work so far has been primarily in producing research and this is a good way to show students how research can practically influence policy,” said Mitra.

]]>This increase is not unique to Fordham or any other university, but is a direct result of the legislation, said Gregory Pappas, the assistant vice president for Student Affairs and dean of Student Services. Fordham has been providing services for students with special needs for 10 years, but the growing case load has made it necessary for the University to step up its efforts. “More and more students with disabilities want to come to Fordham and want to be reasonably accommodated so that they can be successful,” Pappas said.

Disability Services is responsible for reviewing documentation verifying a student’s disability, coordinating reasonable accommodations for students with various other university offices and monitoring the students’ progress. The office provides services for the undergraduate colleges and professional schools. Until last year, the coordinator’s job was a part-time position filled by graduate students. Pirozzi was hired to work full-time in November 1999 when the case load became too great for part-time help. A majority, 66 percent, of students who use her office have learning disabilities such as dyslexia and Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD).

Another 23 percent have physical disabilities and the rest suffer from psychological disabilities, such as bipolar disorder and depression. Pirozzi’s day-to-day include activities such as providing note-takers and interpreters for hearing-impaired students and arranging for extended test-taking time for students with learning disabilities. This semester, she organized a six-week sign language course for students, faculty and administrators, and she worked with University Librarian James McCabe and the Office of Development to establish an Assistive Technology Lab in Walsh Library. Next semester, Disability Services will host the first Students With Disabilities Awareness Day.

]]>