Environmental themes can clearly be seen in scripture, and not just in an incidental way, said Elizabeth Johnson, C.S.J., professor emerita of theology. That’s the message of her new book, Come, Have Breakfast: Meditations on God and the Earth, published earlier this year by Orbis Books.

“This isn’t just [one] point in the Bible,” Sister Johnson said, “it runs through everything—Genesis and the Psalms and the prophets and the Wisdom literature and … into the very last book of the New Testament. You could trace this theme all the way through.” Her book is replete with examples, including these four:

Having Dominion over Nature Doesn’t Mean What You Think.

The biblical passage about God giving humans “dominion … over all the wild animals of the earth” has been taken to justify domination and exploitation of nature, which is “not even remotely” correct, Johnson writes. Rather, in biblical contexts, dominion means good governance—as practiced, for instance, by a stand-in who oversees part of a king’s realm and carries out his will. In Genesis, God is entrusting humanity with wise stewardship of nature, “a responsible service of protection and care,” according to Johnson.

Animals belong to God, and “the Creator is not a throwaway God,” she said. “It’s like anyone who creates anything. You don’t want it to be ruined.”

The Bible Puts Humans in Their Place.

Christian thought and prayer have often treated nature as a “stage set” for the story of God’s relationship with humanity, Johnson writes. But the Bible often paints a different picture, as in Psalm 104, a lengthy paean to the greatness of God’s creation. It glorifies everything from the sun and the moon to Earth’s landscapes and its variety of life, including humanity in the mix. “We’re in the middle, and we’re part of this community,” rather than being at the apex, Johnson said. But “in no way does this deny human distinctiveness” and our special capacities and obligations, she writes.

Animals Have God’s Ear Too.

“Scripture is threaded with verses that depict animals giving glory to God,” Johnson writes. As St. Augustine described it, she said, animals “are giving praise because they’re reflecting the goodness of the Creator.”

Indeed, during the Great Flood in the Book of Genesis, God establishes a covenant with not only Noah but also “every living creature” aboard his ark. “It precedes the covenants with Abraham, Moses, David, and the one established by Jesus,” Johnson writes. “It is never revoked.”

Jesus Valued Nature.

Raised as an observant Jew, Jesus was steeped in the creation theology of the Jewish religious tradition, Johnson writes. He viewed nature with fondness and wonder and speaks of its intrinsic value: In the Gospel of Matthew he speaks of “the lilies of the field” that “neither toil nor spin” yet are clothed in glory, as well as “birds of the air” who “neither sow nor reap” yet are cared for by God nonetheless.

“Pope Francis calls it the gaze of Jesus—like, how did Jesus look on the natural world?” Johnson said. “That gaze is what we should be trying to emulate.”

]]>Answering a call from Pope Francis, Fordham is indeed a place committed to taking “concrete actions in the care of our common home.”

Here are some updates from the first quarter of 2024, from student sustainability interns to “cool” foods to fun community events that make an impact.

Facilities

In January, 11 more undergraduate students joined Fordham’s Office of Facilities Management as sustainability interns to help the University in its efforts to reduce its carbon emissions. They’re working on projects connected to AI-enabled energy systems, non-tree-based substitutes for paper, and composting. The office is still looking for three more students to join; email Vincent Burke at [email protected] for more information.

Dining

Stroll into a dining facility at the Rose Hill or Lincoln Center campus, and you’ll find “Cool Food” dishes such as crispy chicken summer salad, California taco salad, and spicy shrimp and penne.

The dishes, which are marked by a distinctive green icon at the serving station, have a higher percentage of vegetables, legumes, and grains, which generally have a lower carbon footprint than those with beef, lamb, and dairy. According to the World Resources Institute—which Fordham partnered with on the Cool Food project—more than one-quarter of the world’s greenhouse emissions come from food production.

In March, the University went one step further by signing onto the New York City Mayor’s Office Plant-Powered Carbon Challenge. The pledge commits Fordham and Aramark to reduce our food-supply carbon emissions by a minimum of 25% by the year 2030.

Academics

This semester, a new one-credit, university-wide experiential learning seminar titled Common Home: Introduction to Sustainability and Environmental Justice was taught by faculty and staff from the Gabelli School, the Center for Community Engaged Learning, the Department of Facilities, the Department of Biology, and the Department of Theology.

Other sustainability-focused courses this semester include the City and Climate Change, the Physics of Climate Change, and You Are What You Eat: the Anthropology of Food (Arts and Sciences); Sustainable Reporting and Sustainable Fashion (Gabelli School of Business); and Energy Law and Climate Change Law and Policy (Law).

Did You Know?

Like most buildings in New York City, the ones on the Rose Hill campus get almost all of their power from power plants fueled by natural gas (along with some solar power). To power a building like Walsh Library, a natural gas-powered plant normally uses 37 million gallons of water annually. But fuel cells like the ones that were installed at the Walsh Library in 2019 actually make their own water, and as as result, Fordham is saving the community the equivalent of 57 Olympic-sized pools each year.

Students Take the Lead

At Fordham Law School, the student-run Environmental Law Review hosted a March 14 symposium that considered the impact of artificial intelligence on environmental law. Panels focused on how regulators and litigators can use AI and the challenge of addressing AI-generated climate misinformation.

In January, Fordham Law student Rachel Arone wrote The EPA Rejected Stricter Regulations for Factory Farm Water Pollution: What This Means, Where Things Stand, and What You Can Do for the Environmental Law Review. And the Law School’s student-faculty-staff collective Climate Law Equity Sustainability Initiative held a series of lunchtime discussions about climate change, law, and policy.

Student groups LC Environmental Club and Fashion for Philanthropy teamed up on March 8 to create reusable tote bags on International Women’s Day. The bags were donated to Womankind, which works with survivors of domestic/sexual violence and trafficking.

The United Student Government Sustainability Committee continues to run the Fordham Flea, a student-run thrift shop that connects students interested in selling old clothes with those looking to buy sustainably. The next flea will take place on April 26 from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. outside of the McShane Center.

Community Engagement

The Center for Community Engaged Learning (CCEL) held an Urban Agriculture and Food Security Roundtable on Feb. 2. The gathering brought together community organizations and leaders from the Bronx to discuss urban agriculture and food security. Attended by Bronx Congressman Ritchie Torres, the meeting was also an opportunity for groups to learn about resources available from the USDA and the New York City Mayor’s Office on Urban Agriculture.

CCEL Director of Campus and Community Engagement Surey Miranda-Alarcon served as a panelist at a March 9 climate justice workshop at SOMOS 2024 in Albany, along with Mirtha Colon, GSS ’98, and Murad Awawdeh, PCS ’19.

Faculty News

David Gibson, director of the Center on Religion and Culture, and Julie Gafney, Ph.D., director of the Center for Community Engaged Learning, attended “Laudato Si’: Protecting Our Common Home, Building Our Common Church” conference at the University of San Diego on Feb. 22 and 23.

Marc Conte, Ph.D., professor of economics, and Steve Holler, Ph.D., associate professor of physics, presented their research around air quality, STEM education, and education outcomes on March 11 at the first night of Bronx Appreciation Week, which the Fordham Diversity Action Coalition organized.

Alumni

On March 14, Tara Clerkin, GSAS ’13, director of climate research and innovation at the International Rescue Committee, delivered a lecture at the Rose Hill campus titled “The Epicenter of Crisis: Climate and Conflict Driving Humanitarian Need and Displacement.”

In Case You Missed It

Here are some sustainability-related stories that you may have missed: In January, economics professor Marc Conte published the findings of a study that examined whether people living in areas with more air pollution suffer more from the coronavirus. The Gabelli School of Business partnered with Net Impact, a nonprofit organization for students and professionals interested in using business skills in support of social and environmental causes. A group of the Gabelli School Ignite Scholars traveled to the Carolina Textile District in Morgantown, North Carolina, to learn the benefits of sustainable and ethical manufacturing.

Upcoming Events

April 12 and 19

Poe Park Clean-up

In celebration of Earth Day on April 22, the Center for Community Engaged Learning is organizing visits to the park, where volunteers can help pull weeds and spread mulch. 10 a.m. – 2 p.m., 2640 Grand Concourse, the Bronx. Sign up here.

April 13

Bird Watching in Central Park

Law professor Howard Erichson will lead students on a birdwatching tour of Central Park, where they hope to spot and identify a few of the hundreds of species that pass through Fordham’s backyard on their annual migration routes. Meet at the Law School lobby at 9:30 a.m. Contact [email protected] to reserve a spot.

April 13

Ignatian Day of Service

Students and alumni will meet at the Lincoln Center campus and walk over to nearby Harborview Terrace, where they will build a community garden with residents. Lunch and a conversation about Ignatian leadership will follow. 10 a.m. – 2 p.m.

Click here to RSVP.

April 15

ASHRAE NY Climate Crisis Meeting

The theme of this meeting of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers is “Challenge Accepted: Tackling the Climate Crisis.” All are welcome.

7 a.m.- 1 p.m., Lincoln Center Campus. Contact Nelida LaBate at [email protected] for more information or register here using code FordhamStudent2024.

We’d Love to Hear From You!

Do you have a sustainability-related event, development, or news item you’d like to share? Contact Patrick Verel at [email protected].

]]>But Raúl E. Zegarra, Ph.D., says that’s all wrong.

“We’re not seeing the decline of religion, but the transformation of religion into new forms and the building of new sacred spaces,” said Zegarra, the winner of the Fordham Curran Center for American Catholic Studies’ fourth annual New Scholars essay contest.

“And liberation theology has been essential in the process of building those new spaces.”

It’s an argument that Zegarra, an assistant professor of theology at the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, makes in his winning essay, “The Preferential Option of the Poor: Liberation Theology, Pentecostalism, and the New Forms of Sacralization.”

The article was published in the journal European Journal of Sociology (Cambridge University Press) in April. In addition to receiving a $1,500 cash prize from the Curran Center, Zegarra was invited to speak at Fordham. He’ll give his talk virtually on Nov. 13 at 5:30 p.m.

Zegarra said he wrote the paper because he knew the narrative about declines in religion clashed with reality on the ground, particularly in South America, where he has done research.

Latin America was where liberation theology flourished with the official blessing of the Catholic Church in the 1970s and ’80s, but the church’s support withered in the face of a backlash.

What Zegarra found is that the backlash might have forced the Catholic Church in Latin America to withdraw its support for the liberation theology movement, but the ideals behind it have lived on through secular institutions.

The New Sacred Spaces

“A lot of the work done for the poor and for social justice started to move to other areas of society—the universities, the nonprofits, human rights activists,” he said.

“For many of these [Catholics], these became the new sacred spaces to care for their neighbor and to love God in that way. The sacred doesn’t disappear; it just takes a new form.”

John Seitz, Ph.D., an associate professor of theology and associate director of the Curran Center, said Zegarra’s research is important because it fosters a conversation about Pentecostalism and Catholicism in Latin America and also features on-the-ground research from communities in Peru.

‘A Product of Religious Commitment’

Zegarra also helps loosen the definition of what counts as liberation theology, which Seitz sees as a positive sign.

“Raúl is pointing to secular organizations and saying that they’re made up of Catholics who are committed to liberation theology principles. We can think then about recognizing the sacred nature of these organizations, even though they’re not ecclesial organizations,” he said.

“How do we decide that religion is gone? It depends on how you define religion. Raúl shows that these organizations are a product of religious commitment and ideas oriented toward the advocacy of human flourishing and the uplift of the poor.”

]]>“Just as now we are erasing over 200 species a day, [the work of missionaries], when wedded to religious supremacy, has worked deliberately and actively to erase religious and linguistic diversity,” said John J. Thatamanil, MDiv., Ph.D., at an event geared towards first-year students at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus on Oct. 11.

“You cannot have an adequate analysis of how we got here without having an understanding of colonialism and imperialism, and you can’t understand how those forces work if you have no account of religious supremacy.”

In his talk “Enchanted Earth: Addressing the Plight of the Earth by Overcoming Religious Supremacy,” Thatamanil, a professor of theology and world religions at Union Theological Seminary and an eminent scholar of comparative theology, drew on the essay “Whose Earth Is it Anyway?” (University of North Carolina Press, 2000), a groundbreaking essay by James Cone, Ph.D.

All first-year undergraduate Fordham students taking the core curriculum class Faith and Critical Reason this semester read the essay. Many were present for the event at McNally Ampitheatre, which was sponsored by the Department of Theology and is part of the undergraduate Theology First-Year Experience program. It was open to everyone and live streamed to the Rose Hill campus.

The Perils of Religious Supremacy

While Cone connected the behavior that leads to slavery and segregation to the exploitation of animals and the ravaging of nature, Thatamanil suggested that those who embrace religious supremacy will inevitably embrace racism and ecological degradation.

In an onstage conversation with Jeannine Hill-Fletcher, Ph.D., professor of theology, Thatamanil said that in addition to Christianity, prominent 18th-century European intellectuals also promoted a form of scientism, which he said elevates the logical above the transcendent. Animism, an orientation embraced by Native Americans that posits that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence, was dismissed as primitive.

That belief in scientism stemmed in part from the metaphor, which was popular at the time, of God as a watchmaker.

“If we imagine nature as a mechanism, not an organism, then there must be a watchmaker. But is the watchmaker present in the watch? No, but maybe the watchmaker’s genius is present in the watch,” Thatamanil said.

“So if God is outside creation, then creation gets desacralized and conveniently becomes handy for capitalism. You can do with it as you please.”

Learning From Other Traditions

There are, in fact, many Christian teachings that do not lend themselves to conquest of the natural world, he said, and by engaging with other faiths, one can rediscover them.

“Imagine missionaries that came to the Americas with … a sense of ‘What do the First Nation peoples have to teach me?’ ” he said.

“So I think our traditions can be helped by each other. An encounter with indigenous traditions, with Buddhism, with Hinduism can recover submerged, suppressed, and repressed elements of our own tradition.”

Claire Harvey, a first-year student at Fordham College at Lincoln Center who is considering a visual arts major and a theology minor, said she was particularly moved by Thatamanil’s telling of how Gandhi welcomed Christian missionaries but also scolded them for being unreceptive to the lessons Hindus could share with them.

“I thought that was really interesting. I had never thought about the connection between colonialism and religious supremacy,” she said.

Likewise, Thatamanil’s take on Cone’s writing made a deep impression on her.

“He made a really great point about the climate crisis, how you have to fight racism if you want to fight climate change,” she said.

“I knew that people of color are disproportionately affected by the effects of climate change, but I had never heard it put like that. It made a lot of sense to me.”

]]>

The gathering was convened by the pope so that representatives from all areas of the church, from cardinals to lay people, could focus on synodality–the process of working together on how the church will move forward. This meeting is the first of its kind to include women as voting delegates.

“I feel so blessed to be a part of this,” said Mollie Clark, a Fordham junior.

“Women’s voices are being honored and heard for the first time in the synodal process. This is such an affirming thing,” said Clark, who acknowledged “a lot of internal struggle at times” with the church’s stance on women’s participation. “I know that God is listening to my voice.”

A Global Conference

David Gibson, director of Fordham’s Center on Religion and Culture and a former Vatican reporter who will accompany the group, said, “It’s simply a global conversation that is the fruit of two years of listening.”

Pope Francis asked for churches and dioceses all over the world to survey clergy and lay members alike as a prelude to the meeting, which he opened on Oct. 4. As part of this process of synodality, or “journeying together,” the same discussions were happening in nations across the globe about how to be a more inclusive church, a less clerical church, said Gibson, as well as how to increase the role of women and young people.

Fordham is the only Jesuit university to send a student group to Rome for this synod convened by Pope Francis–the first Jesuit pope.

Church on the Go

In the spring, Vanessa Rotondo, Fordham adjunct professor and deputy chief of staff to the University’s president, Tania Tetlow, organized a screening of the Hulu documentary The Pope: Answers and was amazed at the high student turnout.

That event inspired her to propose a course called Church on the GO: Theology in a Global Synod to further “develop student understanding of the postmodern church in tandem with and in light of the Synod on Synodality.” Earlier this year, she traveled to Rome to pursue permission for its students to take part in synod-related events.

Student Itinerary

Rotondo and Gibson developed a series of activities for the students while they are in Rome. They will hear from synodal leaders such as Sister Nathalie Becquart, a voting member who helped facilitate the pope’s canvassing of church members worldwide; join press conferences; and take part in community engagement projects with both Villa Nazareth, a house of humanistic and spiritual formation for college students, and Sant’Egidio, a social service agency focused on global peace and interfaith dialogue. The group will also spend time at the School of Peace, where they will participate in an interfaith prayer service and prepare and distribute meals to people experiencing hunger and homelessness.

Rotondo also devised two leadership sessions with the grassroots organization Discerning Deacons that are rooted in active listening and the synodal process. The goal is to give the students a sense of how the synod is working and train them in Ignatian reflection so they can devise an action plan to enhance Fordham’s mission and Catholic identity when they return.

‘Our Church is Alive’

AnnaMarie Pacione, a Fordham sophomore in the group, said the synod gives her hope.

“Our church is alive, and it’s growing, and it’s breathing and listening to everyone, as it should,” she said. “It’s more reflective of God’s love, Jesus’s love, as I know it, with this commitment and responsibility to listen to voices that have been suppressed in the past.”

A Blog for Dispatches

The students will post to the Sapientia blog of Fordham’s Center on Religion and Culture throughout their weeklong trip and will document their experience on the Instagram account @synodalfordham.

In addition to Clark and Pacione, the Fordham students include Eli Taylor, a theology master’s student; Fordham College at Rose Hill seniors Augustine Preziosi and Sean Power; Fordham College at Rose Hill junior James Haddad; Fordham College at Rose Hill sophomores Abigail Adams, Seamus Dougherty, Jay Doherty, and Kaitlyn Squyres; and Fordham College at Lincoln Center junior William Gualtiere.

John Cecero, S.J., Fordham’s vice president for mission integration and ministry, and Michael Lee, Ph.D., director of the Francis & Ann Curran Center for American Catholic Studies, are accompanying the group.

]]>Increasing extreme weather conditions like record-high temperatures and devastating droughts are undoubtedly the result of “unchecked human intervention on nature,” Pope Francis declared in a letter published today expanding on his 2015 Laudato Si’ encyclical.

Since that publication, he said, “I have realized that our responses have not been adequate, while the world in which we live is collapsing and may be nearing the breaking point.”

Pope Francis called out the United States, specifically, in this new apostolic exhortation, titled Laudate Deum, issued on the first day of the Synod on Synodality.

“If we consider that emissions per individual in the United States are about two times greater than those of individuals living in China, and about seven times greater than the average of the poorest countries, we can state that a broad change in the irresponsible lifestyle connected with the Western model would have a significant long-term impact,” he said.

“The ethical decadence of real power is disguised thanks to marketing and false information, useful tools in the hands of those with greater resources to employ them to shape public opinion,” he wrote.

Pope Francis’s Specificity Is ‘Not Accidental’

Christiana Zenner, an associate professor of theology, science, and ethics at Fordham, said, “This is a document that doubles down morally on the centrality of climate crises and the immediate responsibility of ‘all people of good will’ to address them.”

“Pope Francis first dismantles climate denialism by careful arguments, data, precision of terms, and strategic citation of the climate-recidivistic U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops,” Zenner said. “And the penultimate paragraph of the exhortation likewise identifies the ways that U.S.-based climate exceptionalism is problematic. This is as specific about national responsibilities as a pope ever gets, and it is definitely not accidental here.”

The publication coincides with the upcoming U.N. climate change conference that will convene in Dubai in November, much like the release of the 2015 encyclical ahead of the Paris climate conference. The pontiff laments that the Paris Agreement has been poorly implemented, lacking effective tools to force compliance.

“International negotiations cannot make significant progress due to positions taken by countries which place their national interests above the global common good,” he wrote.

Never Mind the Bedroom, ‘the Entire House Will Burn Down’

David Gibson, director of Fordham’s Center on Religion and Culture, said the new publication shifts the controversy among American Catholics from sex to climate change—which has the potential to be even more contentious.

“The focus and controversy in the church that Pope Francis leads has lately been directed toward issues of sex and sexuality and his efforts to make Catholicism more inclusive. The irony is that this papal exhortation will likely be even more controversial for Americans than any issue of sexuality because it demands fundamental changes in our consumerist lifestyles.”

Gibson added, “Many American Catholics want the church to focus on what people do in the bedroom. Pope Francis is saying the entire house will burn down if we don’t change our behavior in every other aspect of our lives.”

]]>In “Ecowomanism, Justice, and the Work of Planetary and Self Care,” Harris, a professor at Wake Forest University, made the case that race, gender, spirituality, and ecology are deeply intertwined and talked about the role of Black women in environmental justice.

“Ecowomanism is essentially an approach to environmental ethics that centers the voices, perspectives, expertise, and scholarship of women of African descent,” she said.

“All over the world, there are women of color who are at the forefront of environmental justice work because it’s our children who are being deeply impacted.”

The starting point for Harris’ conversation with Christiana Zenner, Ph.D., associate professor of theology at Fordham, was “Whose Earth is it Anyway?”(University of North Carolina Press, 2000), a groundbreaking essay by James Cone, Ph.D., who is widely credited as the father of Black liberation theology.

The premise of the essay is that the same logic that leads to slavery and segregation also leads to the exploitation of animals and the ravaging of nature.

“In the same way that James Cone argues that there is a link between justice issues and environmental issues, there is also a deep, deep link between all justice issues and earth justice issues,” Harris said.

All undergraduate Fordham students taking the core curriculum class Faith and Critical Reason this semester have read the essay. Many were present for the event at Keating Hall, which was sponsored by the Department of Theology and is part of the undergraduate First Year Experience program. It was also live-streamed to the Lincoln Center campus.

Harris, who was a student of Cone at the Union Theological Seminary, said that Cone did more than just connect racial justice to environmental justice. Equally important, he credited the indigenous and Black women who came before him for their contributions to the field.

“Dismantling patriarchy is very difficult for men to do in our culture and the African-American community. So it is quite significant that Cone was actually able to get there, and he was able to get there in the midst of his career,” she said.

Harris said that some of her fellow students at Union Theological Seminary, including Jacqueline Grant, Ph.D., and Karen Baker-Fletcher, Ph.D., were instrumental in pushing Cone to make space for Black women.

“That they created a space for his own awakening is one of the most compassionate things that womanists can do,” she said.

“In Buddhism, we call that concept ‘fierce compassion.’ It’s loving someone so much that you hold them accountable to the spirit who they ought to truly be.”

Harris also talked at length about how interfaith dialogue can strengthen the ways one talks about ecological and racial justice.

“The way we talk about climate change today is not how you’re going to be talking about it 20 years from now. You’re going to need new language. Some of it will come from the poetry you write, some of it will come from the articles you’ve written, and some of it will come from the inspiration that you get here tonight,” she said.

Rhea Sidbatte, a first-year student at the Gabelli School of Business at Lincoln Center majoring in Global Finance and Business Economics, watched the live stream from the Lincoln Center campus.

Sidbatte never took philosophy or theology in high school, and Faith and Critical Reason has become one of her favorite classes, she said, because it’s given her the tools to see how theology is relevant to her day-to-day life. She said she was inspired by Harris’ focus on the value of communalism and lived experience.

“When we’re talking about these ecological issues, we have to move the conversation from focusing on doctrines to listening to other people’s stories and hearing where they came from,” she said.

Harris also met with students and faculty of color in a private reception after the conversation. In addition to her appearance on the 26th, Harris also visited the Rose Hill campus on April 27 for a conversation with the Fordham community about DEI frameworks and anti-racist pedagogies and for a gathering where students, faculty, and community members reflected on Fordham’s newly-released Laudato Si’ Action Plan and brainstormed about next steps.

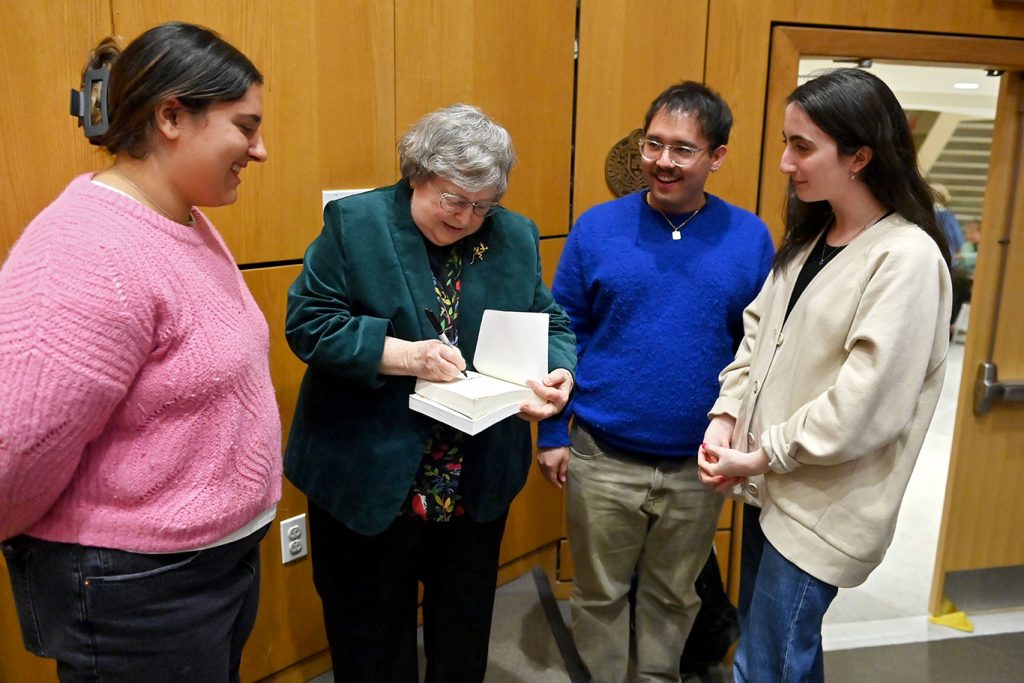

In a wide-ranging lecture on March 21, Elizabeth Johnson, C.S.J., made a case for rethinking humankind’s relationship with the natural world.

In a wide-ranging lecture on March 21, Elizabeth Johnson, C.S.J., made a case for rethinking humankind’s relationship with the natural world.

“We need to change from thinking that we are masters of the universe to realizing that we are siblings, or kin, with all other beings in the community of creation, loved by God,” she said.

Sister Johnson’s talk, “Theology & the Earth: Human Beings in the Community of Creation” helped launch a new initiative, the Elizabeth A. Johnson, C.S.J., Endowed Fund for Theology & the Earth. The fund, which has received initial donations from Margaret Sharkey, PCS ’15, will go to advance the study of theology and our responsibility to the Earth.

Sister Johnson was joined by respondents Jason Morris, Ph.D., professor of biology, and Michael Pirson, Ph.D., the James A. F. Stoner Endowed Chair in Global Sustainability at the Gabelli School of Business.

Creation is Ongoing

The need for change has become apparent: A report issued on Monday by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that the planet is likely to cross a critical threshold for global warming within the next decade.

To spur action, Sister Johnson said humans need to feel a greater connection with living things. That means casting aside old ways of thinking about the world, such as the idea that the creation of the world ceased entirely once it was done.

“One striking metaphor from a British philosopher puts it this way: the Creator ‘makes all things and keeps them in existence from moment to moment, not like a sculptor who makes a statue and leaves it alone, but like a singer who keeps her song in existence at all times,’” she said.

Once we realize we’re part of that same journey, she said, it’s easier to see the intrinsic value in all living things. Pope Francis addressed this in his encyclical Laudato Si, when he wrote, “Creation is a gift in which every creature has its own value and significance.”

“As creatures, we have more in common with other species than what separates us. We are kin to the bear, the raven, and the bugs,” Sister Johnson said.

Obstacles to Overcome

Sister Johnson said we need to stop thinking that humans stand apart from the natural world. She blamed this thinking on the “hierarchy of being,” a concept that ranks beings according to their “spirit.” In it, rocks are at the bottom, followed by plants, animals, humans, and angels.

“Instead of a circle of kinship, this structures the world as a pyramid,” she said, noting that in the European world, this also led white men to rank women and minorities below them.

Who Needs Who?

One way to shake off the idea that humans are superior to all else is to engage in a thought experiment.

“Take away trees, and humans would suffocate. Take away humans, and trees would do just fine,” she said. “So who needs who more?”

Ultimately, human hubris about our place in the world needs to be addressed through what Sister Johnson called a “robust creation theology.” She conceded that to some religious ears, it might seem strange to be “converted to the Earth,” but noted that in Laudato Si, Pope Francis provided guidance with his words:

“Eternal life will be a shared experience of wonder, in which each creature resplendently transfigured will take its rightful place.”

“You know that famous question’ Will I see my dog in heaven?’ The answer is right here,” Sister Johnson said.

Anna Nowalk, a senior at Fordham College at Lincoln Center majoring in theology, was eager to see Johnson speak after reading her book She Who Is (Crossroads Publishing, 2002).

“The idea that God is lovingly willing us into existence constantly is one of my favorite theological concepts,” she said.

“I’m also really glad that they had someone from the Gabelli School there. If you’re talking about the need to have a sense of conversion to the environment, I think it’s very important to include business in there.”

Christian Ramirez, a senior at Fordham College at Rose Hill also majoring in theology, said She Who Is radically changed the way he thinks about faith and brought his copy for her to sign.

“I love this idea of the circle of the kinship of creation, rather than a pyramidal hierarchy of being. I was really interested in how she was going to incorporate feminist theology into ecological theology,” he said.

“When we create a circle of kinship where the man is displaced from the top and becomes part of the circle, that elevates all creatures.”

Taking the name Francis, he became the first pope to be a member of the Society of Jesus, the first from the Americas, the first from the Southern hemisphere, and the first from outside Europe since the eighth century.

At Fordham, faculty and staff reacted to the news with words like “shocked” and “an ingenious choice.” Two years later, when the pope visited New York City as part of his first visit to the United States, members of the Fordham community flocked to Central Park to catch a glimpse of him and shared their hopes for his tenure.

“As the first Jesuit to serve as pope, Francis has done the work of St. Ignatius, reminding the faithful of the central values of the Gospels and calling us to action,” said Tania Tetlow, president of Fordham.

“As a Jesuit community, Fordham celebrates the Pope’s tenth anniversary in the chair of St. Peter, and we wish him all the blessings of faith in his holy work.”

On the cusp of his 10th anniversary, Fordham News spoke with experts on the impact Francis has made on the papacy as an institution, race and gender, and the environment.

Thomas Worcester, S.J., professor of history and co-editor of The Papacy since 1500: From Italian Prince to Universal Pastor. Cambridge (Cambridge University Press, 2010)

I think Pope Francis grew into the job. He likes the pastoral side of it very much. Compassion and mercy are what the church should be about, and I think he exudes that himself and the style he has as pope.

I think Pope Francis grew into the job. He likes the pastoral side of it very much. Compassion and mercy are what the church should be about, and I think he exudes that himself and the style he has as pope.

He’s not as happy dealing with the Roman Curia. The pope is supposed to be a unifier in the church, and I think he wants to be that. In some ways, his inclination is toward reform, and yet at the same time, there’s a caution in him, which I think all folks have to some extent.

He makes clear that change is not just possible, but desirable. Just the very fact that he understands synodality as something that has an emphasis on listening—that the pope himself needs to listen to not just other bishops, but more broadly than that—is a major change from a style that was more top-down for much of the history of the papacy.

There are some aspects of his leadership that are also very Jesuit. Some have said that those who favor access to abortion for women should not receive communion. Francis is totally against that. He makes clear that the Eucharist is not a “prize for the perfect,” but a “medicine for the weak.” He’s got a good grounding in that. In the past, Jesuits have traditionally been favorable to people receiving communion frequently, with relatively few obstacles. That’s an area where I think Francis is very Jesuit, with an emphasis on access to mercy.

Bryan Massingale, S.T.D., professor of theology and the James and Nancy Buckman Chair in Applied Christian Ethics

He will go down as one of the most consequential popes in modern church history because his signal accomplishment has been to foster a community of open dialogue and discussion.

I never thought I would ever hear a pope say words like, ‘Who am I to judge?’ the way he did in 2013, in response to a question about gay priests.

The phrasing reverses the average person’s understanding of the church’s relationship with gay and lesbian people. Before then, the Catholic church was seen as very judgmental of LGBTQ persons and very hostile and unapproving of LGBTQ relationships. That single question ushered in a whole new era and effectively challenged that stance of knee-jerk condemnation that the Catholic church has been more associated with.

The phrasing reverses the average person’s understanding of the church’s relationship with gay and lesbian people. Before then, the Catholic church was seen as very judgmental of LGBTQ persons and very hostile and unapproving of LGBTQ relationships. That single question ushered in a whole new era and effectively challenged that stance of knee-jerk condemnation that the Catholic church has been more associated with.

More than any other pope, I think that Francis also has taken on racism as a major challenge to the Christian conscience. After George Floyd was murdered in 2020, that week in his general audience in Rome, he took a very unusual step of praying for him by name. Then he followed that with a statement that was really important. He said, ‘We cannot tolerate or turn a blind eye to racism and exclusion in any form, and yet claim to defend the sacredness of every human life.’

What’s brilliant about that is how he grounds the opposition to racism within the church’s commitment to a pro-life stance and the sacredness of every human life. He very much put his cards on the table that safeguarding the dignity of Black lives is part of the respect owed to every human life. The fact that that statement was not picked up a lot by the American bishops or pro-life Catholics in the United States shows that Francis has a more prophetic understanding of the implications of being pro-life than many American Catholics are comfortable with, especially when it comes to racism.

David Gibson, director of Fordham’s Center on Religion and Culture

It’s been a remarkable time, and for so many people it’s been inspiring. It’s as though the windows are open and light and fresh air are coming in. For another segment of the church, that’s a very unsettling, even threatening prospect. So his papacy has sparked far more backlash than I expected. But the backlash and the opposition to Francis make you realize how much this was needed in the church. There have been so many decades of quashing dissent or even discussion, and now people are free to speak their minds.

It’s been a remarkable time, and for so many people it’s been inspiring. It’s as though the windows are open and light and fresh air are coming in. For another segment of the church, that’s a very unsettling, even threatening prospect. So his papacy has sparked far more backlash than I expected. But the backlash and the opposition to Francis make you realize how much this was needed in the church. There have been so many decades of quashing dissent or even discussion, and now people are free to speak their minds.

It’s interesting that so much of the fierce opposition has come from a certain segment of American Catholics. I think it’s important to keep it in perspective. The U.S. Church counts for about 5% of the global Catholic population of 1.3 billion. The opposition to Francis is relatively small, but it is very vocal, and very passionate, to the point of even being destructive.

He’s made it so clear that everybody should be free to speak their mind, and that no topic is out of bounds. For a center that is founded on public discussion, that’s oxygen for us. Francis has also stressed the importance of culture as a connecting tissue for different people. I totally agree. Culture provides a rare piece of common ground for discussions. People can come together over the arts and literature and other cultural manifestations.

He’s elevated the role of lay people, especially women. At the Vatican, putting them in offices over clerics—that’s unheard of. But there are still concrete steps that need to be taken in order to have any difference on the ground. Laypeople need to be able to preach. Women need to be able to preach. Women need to be ordained as deacons. Unless there’s some upsurge in priestly vocations, which doesn’t seem likely, there need to be other things that are going to affect changes on the ground in parishes.

Christiana Zenner, Ph.D., associate professor of theology, science, and ethics

One of the things that has continued to surprise and delight me and other watchers of ecological ethics is how Francis’ encyclical about the environment, Laudato Si’ continues to resonate with people of many faiths, as well as those with none. The planetary reach of that document seems to be real. People ranging from secular Jewish feminists to atheist students to “cradle to grave” Catholics have all found things to love in this document.

One of the things that has continued to surprise and delight me and other watchers of ecological ethics is how Francis’ encyclical about the environment, Laudato Si’ continues to resonate with people of many faiths, as well as those with none. The planetary reach of that document seems to be real. People ranging from secular Jewish feminists to atheist students to “cradle to grave” Catholics have all found things to love in this document.

What’s distinctive to him in the contemporary era is the way that this encyclical is part and parcel of how he walks the walk and talks the talk. Popes can write lots of documents that have different kinds of impact, but it seems to me that Pope Francis has also really tried to embody what’s in this document. He has worked interreligiously on climate change and environmental refugees and migration more generally by talking about global capitalism and its excesses and has by himself modeled a more modest approach, from his domestic quarters to the footwear he chooses. So I think that it is a document with which his own personal charism is uniquely integrated and I think for that reason it will be a lasting legacy of his papacy.

Pope Francis also talks a lot about the wisdom of indigenous cultures and ecological values, and the primacy that ought to be accorded to indigenous communities before major projects are done on their land. This is a pretty radical statement for a historically universalizing, colonizing church.

So I would love to see him and the Catholic church continue to explore what it means to live up to those best ideals.

]]>The project was spurred by a 2018 report by the Society of Jesus that publicly disclosed the names of its members who were credibly accused of sexually abusing minors, as well as a report that year by a Pennsylvania grand jury that found similar findings in diocesan priests. It was funded by a $1 million gift from a private donation.

On Thursday, Jan. 26, the group released its final report, featuring research projects conducted by 18 teams from 10 Jesuit universities. In addition to Fordham, the initiative included lay and clergy faculty from Creighton, Gonzaga, Georgetown, Loyola Chicago, Loyola Maryland, Marquette, Rockhurst, Santa Clara, and Xavier universities.

The research projects addressed topics connected to the Society of Jesus, but were not limited strictly to it. There was often overlap with other parts of the Roman Catholic Church, such as specific parishes. They covered six themes: Jesuits and Jesuit Education; Education; Institutional Reform; Moral Injury and Spiritual Struggle; Race and Colonialism; and Survivors and Survivor Stories.

In addition to team projects, the initiative featured a three-day conference hosted at Fordham in April 2022 as well as eight webinars, four of which were devoted to historically marginalized U.S. communities.

Bradford Hinze, Ph.D., the Karl Rahner Professor of Theology and director of the initiative, said after two and half years, he is more impressed than ever with how much time and energy scholars have devoted to try to address past wrongs and prevent future ones. Their dedication has been “a bit overwhelming,” given how painful the subject is, but is also a source for optimism.

“My big take away is that we need to find ways of building greater relationships of collaboration and more transparency,” he said, “because here we have a lot of lay people—not all are lay people, but most are—who are committed to the Jesuit identity and mission.”

That commitment manifested itself in reports that varied from one about an individual abuser by the team at Creighton University to one examining the best way to tell survivors’ stories by Georgetown University’s Gerard J. McGlone, S.J. A report from Fordham professor C. Colt Anderson, Ph.D., that focused on reforming Jesuit schools noted that “pastoral care principles influence disciplinary processes.”

“There is an emphasis on being patient and merciful that allows for inferior performance and outright misbehavior,” he wrote.

“As a member of a religious order told us, there is confusion between what is simply sinful and what is criminal.”

Key Findings and Recommendations

The report includes six key findings and specific recommendations for learning and action.

The first of the group’s findings is that there is “a divide emerging in research and practice between those focused primarily on “safeguarding” and those focused on what the group is calling “historical memory work.” Safeguarding is focused on preventing present and future abuse, while historical memory work produces research on what happened in the past, in many cases performing a very close analysis of instances of abuse.

Hinze said the group chose to emphasize the importance of historical memory work in response to the forward-facing nature of the Society of Jesus’ most recent Universal Apostolic Preferences, which are in essence the religious order’s list of priorities. He noted that representatives from the Society of Jesus in Rome had been very cooperative, but the group still felt the need to highlight the importance of looking to the past.

“The Apostolic preferences all aim to start from right now and look forward. But if you only do that, you don’t really spend time pondering, reflecting upon, and truly meditating on what were the causes and contributing factors that led up to this, and what were the historical, institutional, and cultural repercussions,” he said.

Another finding highlights the fact that although the first sexual abuse cases in the United States were widely reported as early as 2002, very little research has been done to examine how much abuse was committed against Black, Latin American, Asian, Pacific Islander, and Native American populations.

Fordham Faculty Perspectives

Bryan N. Massingale, S.T.D., the James and Nancy Buckman Chair in Applied Christian Ethics at Fordham, contributed in this area; his study, “Clergy Sexual Abuse in African American Communities,” will be published in October. He surveyed the literature about the sexual abuse crisis to see how many church dioceses tracked the race and ethnicity of survivors and found that only one did, and it only started doing so in 2015.

This is a glaring omission, he said.

“We know for a fact that in many cases, dioceses and religious orders deliberately sent priests with problematic histories into Latino and Black communities, precisely because these communities would be the least likely to report instances of abuse,” he said.

It’s for this reason, Massingale said, that although 4% of American Catholics are Black, it’s fair to assume that more than 4% have experienced sexual abuse. Compounding the problem, he said, is the fact that Black people may not relate to the ways others are processing their abuse. In the course of his research, he spoke informally with two Black men who’d experienced abuse, and discovered that they refused to accept the popular “victim survivor” label.

“They said ‘I’m not surviving anything. I’m coping.’ And it struck me that maybe another reason why we need to pay attention to this is because even the language we use doesn’t resonate universally across human communities,” he said.

Lisa Cataldo, Ph.D., associate professor of mental health counseling and spiritual integration at Fordham’s Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education, said her future teaching will forever be informed by the work she did with the initiative. In her research project “Bearing Witness When ‘They’ Are Us: Toward a Trauma-Informed Perspective on Complicity, Moral Injury, and Moral Witnessing,” Cataldo attempted to answer a question she asked herself when the Pennsylvania Grand Jury report was published: Why am I still shocked?

“We’ve been hearing about this since 2002, if not before,” she said.

“I realized that this cycle of being OK, and then being overwhelmed with shock and horror, and then having the feeling sort of recede into the background, is the same cycle that a trauma survivor experiences.”

No solution to a trauma-based problem can work unless it addresses the trauma, she said.

“All the safeguarding that has been put in place has been very effective, and it’s absolutely vitally important. I’m not discounting any of that, but you will never heal without addressing the trauma, and that means having accountability, responsibility, dialogue, honesty, and truth telling,” she said.

“It’s like closing the barn door after the horses are out.”

Telling It Like It Feels

Cataldo suggested that a crucial part of the healing process should involve people who Israeli philosopher Avishai Margalit dubbed the “moral witnesses.”

“In order to really stand up for and call attention to the suffering imposed on one group by another group of people, the moral witness has to be someone who speaks the truth,” she said.

“But the moral witness doesn’t just tell it like it is. The moral witness tells it like it feels. To be a moral witness, the person needs to have been either a survivor themselves or have something at stake. You have to have skin in the game.”

The participants in Taking Responsibility fit that bill, she said, by virtue of working for Catholic institutions and working to highlight the painful truth.

The project has inspired Cataldo to do more herself. This fall, she will oversee the unveiling of GRE’s Advanced Certificate in Trauma-Informed Care program. Importantly, she said, the certificate program explores how spirituality can be both a balm for people healing from trauma and a shield that prevents them from acknowledging their own trauma.

“It’s very important to understand how unexamined religious practices and religious structures like the Catholic Church can sometimes re-traumatize or compound the trauma of people if they don’t understand how trauma and faith intersect,” she said.

]]>For Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, a new book of poetry serves as a tribute to both types of “holy lands,” be they far or near.

Holy Land, (Paraclete Press, 2022) a collection of 87 poems that won the Paraclete Press Award in 2021 and was published in October of this year, was in fact inspired by a trip that she took to Palestine in 2019.

The first chapter, Christ Sightings, is based on her time in Palestine. What follows is a series of chapters—Crossing Ireland, Ancestral Lands, Sounding the Days, Literary Islands, and Border Songs—that were inspired by her travels to places that may not be the Holy Land, but are holy to her just the same.

Crossing Ireland features poems O’Donnell composed after visiting the Emerald Isle, while Ancestral Lands features meditations on her native northeast Pennsylvania. The poems in Sounding the Days and Literary Islands expand the notion of holy lands into the spiritual, emotional, and intellectual realms. The book ends with 15 triolets inspired by the crisis at the United States-Mexico border that dominated the news in 2019.

Crossing Ireland features poems O’Donnell composed after visiting the Emerald Isle, while Ancestral Lands features meditations on her native northeast Pennsylvania. The poems in Sounding the Days and Literary Islands expand the notion of holy lands into the spiritual, emotional, and intellectual realms. The book ends with 15 triolets inspired by the crisis at the United States-Mexico border that dominated the news in 2019.

The book’s first poem, “The Storm Chaser,” was inspired by a visit to the Sea of Galilee. The view of the sea has changed little in the 2,000 years since Jesus and his disciples were said to have spent time there, so O’Donnell said it was easy to create a picture in her head of what it would have been like then.

Running along the Sea of Galilee,

I see you in your boat, tall brown

man that you are, standing in the prow,

“All of these stories that I had been hearing all of my life in church in the Gospel readings suddenly became so much more powerful and real when I was in the landscape where they unfolded,” she said.

“There was something electrifying about walking literally in the footsteps of Jesus and being in those spaces where these events took place.”

As moved as she was by the geography there, O’Donnell said she knew didn’t want to limit herself strictly to one location.

“It’s arguable that there are no places that aren’t holy, that aren’t sanctified in some way by human experience,” she said, noting that Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, is considered sacred ground because nearly 50,000 soldiers died there during the infamous Civil War battle.

“I used to take my kids there, and I remember having this eerie sense of so many lives being lost in this peaceful, rural place. You know, the very dirt of the ground being watered by the blood of human beings. That’s a sacred ground.”

When she started considering other holy lands she’s visited, it dawned on her that many of them are places that most people don’t think of as holy. In “304 Washington Street,” for instance, she considers growing up in a small town just south of Scranton, Pennsylvania.

Squat and square, her pea green shingles

made her strange on our straight street

lined by wood white houses,

their faces bland and neat.

“Northeastern Pennsylvania was very beautiful at one time and then was ruined by coal mining. The land is sacred in the sense that that’s where my immigrant ancestors settled down, where they lived and died, and that’s where my family flourished,” she said.

From there, O’Donnell made a leap to the idea that parenthood can be holy ground, as can being a sibling. And if one lives a creative life, the bonds one forms with practitioners of the past are also relevant. In the Literary Islands chapter, “Flannery’s Last Day” marks the anniversary of the Aug. 3 death of Flannery O’Connor, whose family trust endowed Fordham with a grant in 2018 to promote scholarship of the writer.

Today of all days you would show up

making sure you are not forgotten.

Your suffering at the end was true,

The final chapter, Border Songs, was arguably the toughest in which to envision a connection with God, she said. The poems are meant to be “poetry of witness,” a term that the Nobel-prize winning Polish writer Czeslaw Milosz coined to describe his writing about the experience and aftermath of World War II. She wrote the poems in an attempt at accompaniment, as the world watched the horrors at the border unfold during the spring and summer of 2019.

“I felt as though it was important to meditate, to pray for, and to memorialize these people who are forgotten—people who no one cares about, people who are alienated and don’t belong,” she said.

She decided the best form to use was the triolet, a song-like poem which features several lines that are repeated several times.

“The idea is to create this haunting incantatory effect, particularly when the poem is read and listened to out loud,” O’Donnell said.

One of the first ones she wrote, “Border Song #2,” was inspired by a report that immigrants who were taken into custody were having their rosary beads confiscated.

They confiscate your rosary when you come.

I cannot go to sleep without one.

Thumbing each bead until the night is done.

They confiscate your rosary when you come.

She penned 15 triolets in short order.

“I didn’t have to look very hard. Every day, there was a new outrage, a new photograph or quotation that I would see in the news that would trigger another triolet,” she said.

She noted that in his 1946 book Man’s Search for Meaning, Holocaust survivor Victor Frankl declared that God was with him in the concentration camp, “suffering and dying with us every day.”

“That sense of God dwelling in brokenness and in sorrow and horror as well as in the sunny places that we remember happily—that’s part of what this book is about,” she said.

“There is divinity in everything—even in those dark places that we don’t necessarily want to be. There are times when we have to celebrate the darkness, and some of these poems attempt to do that.”

]]>