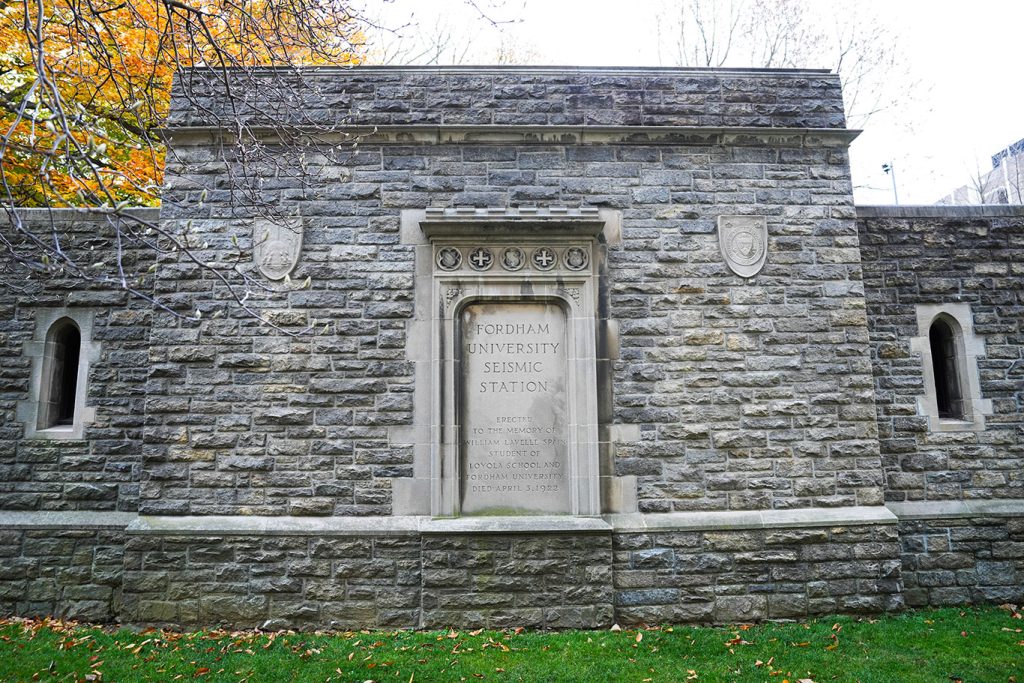

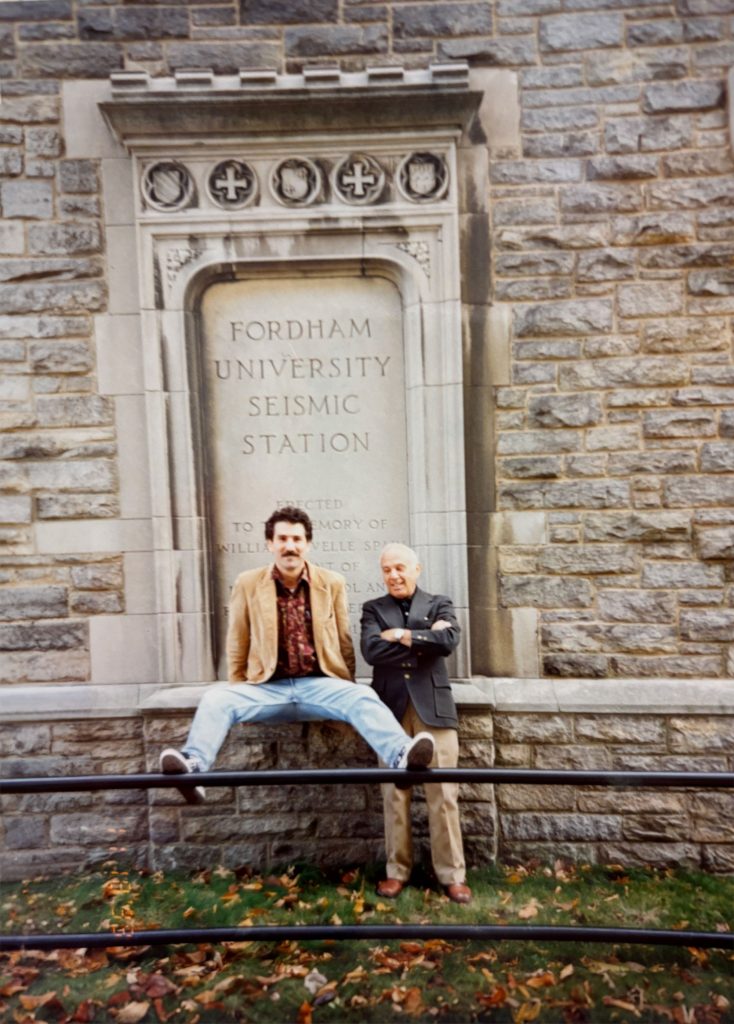

Since 1924, Jesuits and their lay counterparts have been measuring earthquakes in this one-story Gothic structure, which currently stands next to Edwards Parade on the Rose Hill campus. Its equipment detects temblors around the world, including the 4.8 magnitude earthquake that rattled the area in April.

The observatory, which consists of an unassuming above-ground structure and a concrete vault 28 feet underground where the seismic instruments reside, is easy to miss. But it has played an important role in the advancement of seismology and physics over the years.

Stephen Holler, Ph.D., chair of Fordham’s physics department, who maintains the station, said it’s important to “keep an eye” on the planet and its rumblings.

“We’re always learning things about the Earth, and especially in the kind of high-density area that we’re in, it’s useful to monitor for earthquakes [and other tremors],” he said. “Maybe, in the event that something is happening or changing, we can potentially prepare for it.”

In the years that it has been operational, the station has recorded many earthquakes, including an 8.6 magnitude quake that struck Alaska in 1946 and a 7.7 magnitude quake that struck Taiwan in 1999. Holler is often called on by the media to discuss earthquakes when they strike the area.

Digging Deep

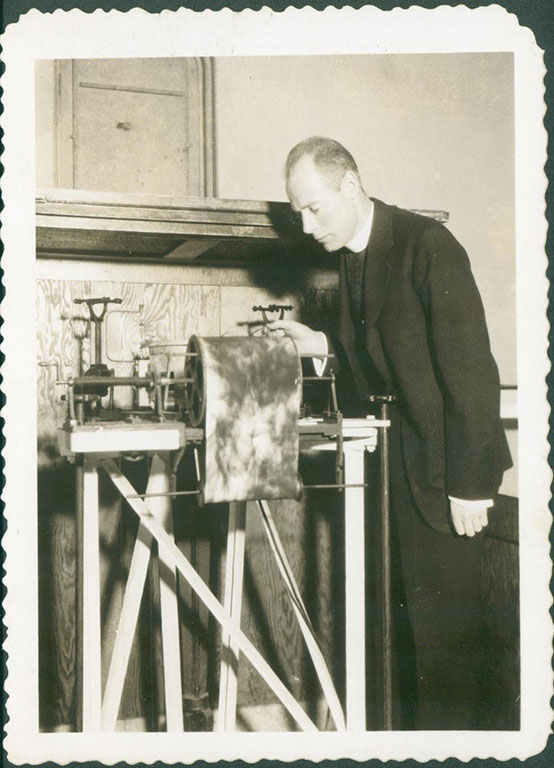

Fordham first got involved in seismology in 1910—along with nine other Jesuit colleges—through the Seismological Society of America, which had a Jesuit priest as one of its founding members. That year, a seismograph was installed in the basement of Cunniffe Hall. In 1920, Joseph J. Lynch, S.J., a physics instructor, took over the station.

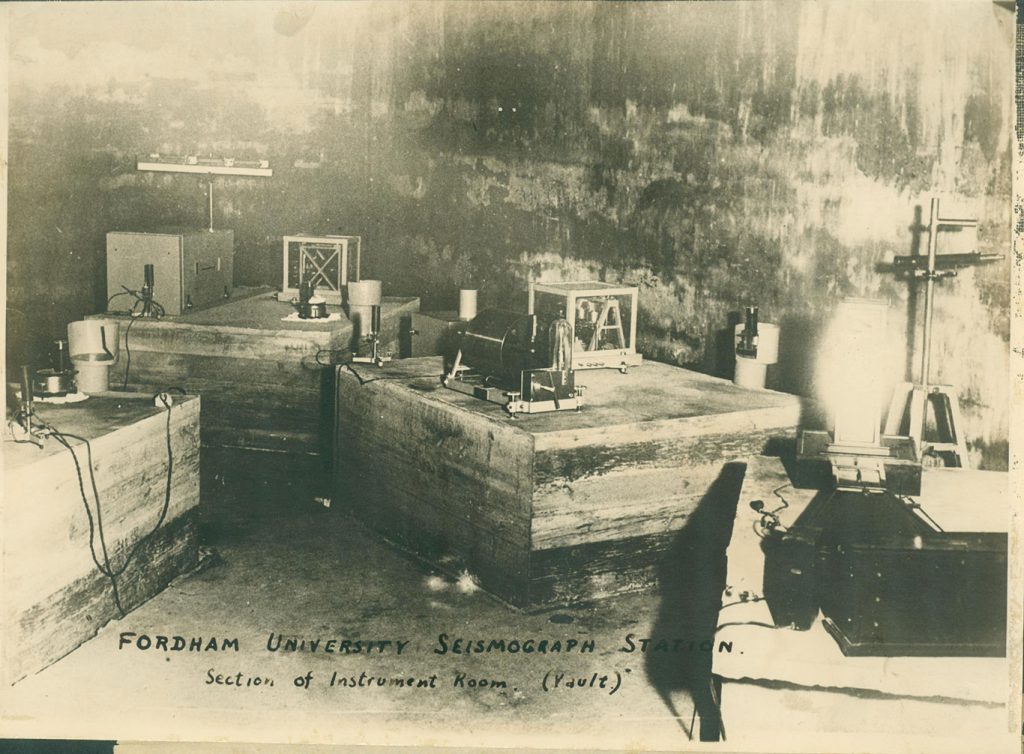

At the time, seismographs worked by utilizing a suspended mass—such as a weight—that remained relatively stationary, while the base of the instrument, which was fixed to the ground, moved during an earthquake. A recording of the relative motion between the mass and the base was recorded, providing a measurement of the ground shaking.

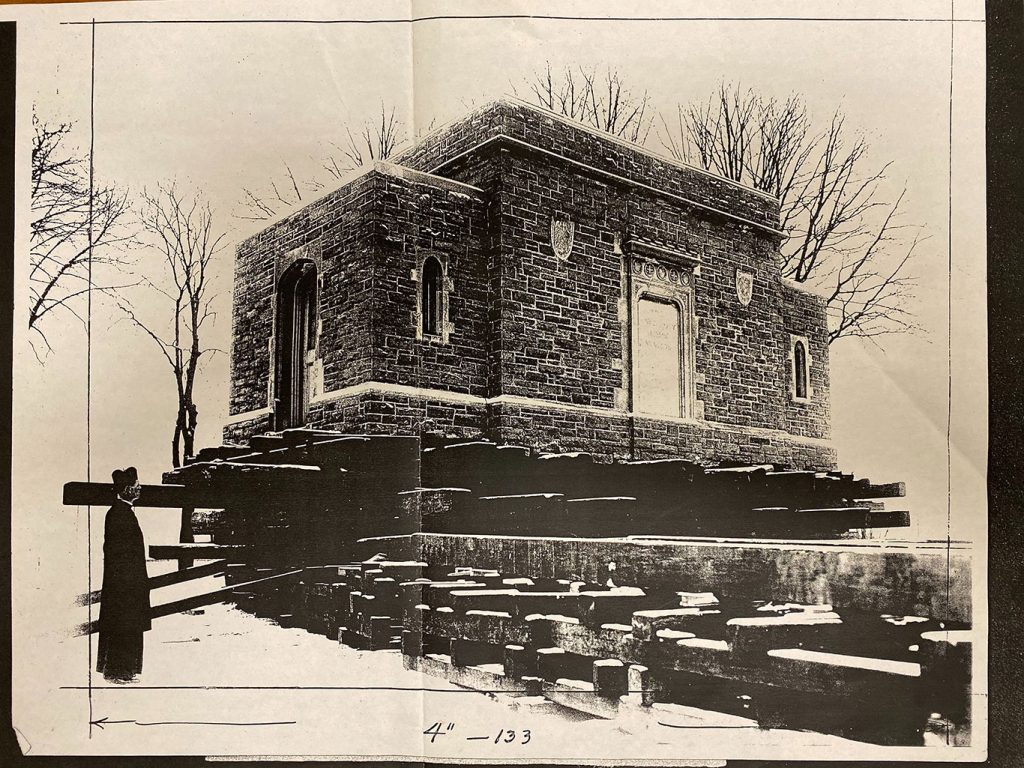

But the instruments worked best when isolated and in close contact with the bedrock. So in 1922, the University used stone acquired from a recent subway excavation to construct a building with underground space where they could operate with minimal disruption. It was originally built in the spot where Faber Hall now stands.

A Plaque From the Pope

Funding for the construction was provided by William Spain, whose son William, a physics student at Fordham, died that year. It was formally blessed by Bishop John Collins, S.J., Fordham’s 13th president, in a ceremony on Oct. 24, 1924. To honor the occasion, Pope Pius XI sent a bronze plaque with an image of St. Emidio, the divine protector against earthquakes, that is still embedded in the building’s exterior door.

In Pop Culture

Almost immediately after it opened, it became an object of fascination. A working model of the station was displayed at the 1939/1940 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, and Fordham displayed an operational seismograph at the 1964/1965 World’s Fair as well.

Father Lynch was routinely one of the first to report major seismic events around the world to media outlets. In April 1946, Life Magazine stated that the “Jesuit seismologist is America’s best-known interpreter of things that shake the earth, including milk trains, quakes, seismic waves.”

The station even became a part of pop culture. In a 1974 episode of the television show M*A*S*H. (starring Alan Alda, FCRH ’56), Colonel Henry Blake joked that he snores so loudly that he “even got a fan letter once from the seismograph people at Fordham.”

A Revival

In 1970, Father Lynch published a reflection titled Watching Our Trembling Earth for 50 Years (Fordham University Press), which recounted the ways he and fellow Jesuits worked together to perfect the science of seismology. Among other anecdotes, he noted how one night in 1929, in the course of calibrating the station’s clock with one at the Naval Observatory in Arlington, Virginia, he stumbled on bootleggers who were bottling whiskey on campus.

For several years after Father Lynch’s death in 1987, the station was either dormant or tended to by students who pursued seismology as a hobby.

In 1996, physics professor Ben Crooker took over supervision of the student club that had been using the equipment. By then, the field had changed a lot with the advent of the internet and increased computer power.

In 2001, thanks to a donation from an unidentified alumnus, Fordham was able to purchase a Guralp DM24 CMG3T machine, which combines the functions of a seismometer and digitizer. The University officially rejoined the international seismology community.

The Station Today

Today, measuring an earthquake now is akin to conducting a CT scan on the planet, with multiple stations—including Fordham’s—reporting observations from around the country to the United States Geological Survey (USGS) data repository in Boulder, Colorado.

“Fordham’s station is like one cell in a giant camera,” Crooker told Fordham News in 2007, “used to build a seismic map of the Earth.”

The Guralp, which looks like a coffee can with wires poking out of it, sits on a concrete pedestal beneath a plexiglass box and a blanket, which keeps it dust free and at a constant temperature. The data it collects is sent to a computer in Freeman Hall, which then relays it to USGS.

The rest of the vault is occupied by dormant equipment once used by Lynch and his successors. Every year on the day before commencement, Holler opens up the station to graduating physics students who marvel at the antiquated instruments.

“They’re kind of museum pieces, but they’re fantastic for quizzing the students on their physics fundamentals,” he said.

At roughly 3:15 p.m., the moon will pass directly in front of the sun as part of the first total solar eclipse to happen in the United States since August 2017.

During the 2017 eclipse, the moon covered about 65% of the sun in New York City. This year, the path of totality—where the moon obscures 100% of the sun—will stretch over Syracuse, just 200 miles from New York City. This means the moon will obscure almost all of the sun in the New York City area. The next time an eclipse will happen in the Northeast will be in 2079.

The eclipse will begin around 2:10 p.m. and finish at around 4:36 p.m., but the best time to watch will be from 3:15 to 3:30 p.m.

Robert Duffin, Ph.D., a lecturer of physics who teaches astronomy at Fordham’s Rose Hill campus, said the fact that the eclipse will be happening in the late afternoon means that any open space will suffice for viewing the event.

“You want to be in a wide space so you can see the effects of 85% coverage. It’s going to be dim, and you’re going to see a difference,” he said.

Eclipses play an important role in Duffin’s class; among other things, students learn that more than 2,000 years ago, Aristotle estimated that the diameter of Earth’s shadow at the moon during a partial lunar eclipse was two and a half times the diameter of the Moon. Ancient Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos then determined from observing the umbra (or dark shadow on the surface of the Earth) during a solar eclipse that the Earth’s diameter is about three and a half times the Moon’s diameter.

Here are some great places to catch the eclipse. Remember, never look directly at the sun without protective glasses or other safe viewing methods.

The Bronx

Rose Hill campus

The Fordham Astronomy Club will be set up in the middle of Edwards Parade from 3:15 to 3:45 p.m. The group will use a telescope to project the eclipse onto a screen for safe viewing and also have telescopes set up for the viewing of Jupiter and Saturn, which will be visible during the eclipse. Contact Jackson Saunders at [email protected] for more information.

Wave Hill

The 28-acre estate in Riverdale will be hosting a viewing party from 12 to 5 p.m. Visitors will have the chance to pot seeds, make a festive eclipse party hat or celestial floral headband, enjoy live music and storytime with the Riverdale Library, and see the eclipse with free viewing glasses. Read more.

Manhattan

Umpire Rock, Central Park

The 15-foot-high, 55-foot-wide outcropping just north of Hecksher Playground is the perfect place to take in the show near Midtown Manhattan. Enter the park at West 62nd Street and Columbus Circle.

Pier I, Riverside Park South

Jutting into the Hudson River at West 70th Street, this spot guarantees unobstructed views, with the added bonus of seagulls who might not quite know how to react to the changing light.

American Museum of Natural History

The museum will offer family-friendly educational activities and will give out eclipse glasses while supplies last, from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Read more.

Brooklyn

Green-Wood Cemetery

The cemetery will host a free event from 1:30 to 5 p.m. featuring special-edition glasses and telescopes equipped with solar filters. There will also be amateur astronomers to help operate telescopes and answer questions, along with self-guided explorations and artist-led installations. Read more.

]]>Prodan published a paper in PhysRevLett that explored how a microtubule’s structure and its ability to store energy along its edges could be useful in areas like cancer research.

“My hypothesis is that through evolution, cancer-derived microtubules actually found a way to get rid of these energy storage methods,” she said.

One of her goals is to research ways to physically manipulate a cancerous microtubule into one that is noncancerous.

“Then you have another method to treat cancer,” she said.

Connecting Fields

Prodan’s work connects biology with materials science, a field that combines areas like physics and biology to better understand the properties of different materials and how they can be used. This field is useful in areas like engineering, energy conversion, and telecommunications.

“I have two areas that seem disconnected, cancer research and engineering new materials, but they are highly interconnected,” said Prodan, who came to Fordham from the New Jersey Institute of Technology this fall. “The main relationship between them is physics.”

In the course of researching microtubules, Prodan began noticing similarities between them and a new type of material, topological insulators. A topological insulator is a material whose surface behaves as an electrical conductor while its interior behaves as an electrical insulator, she said.

The possibilities of topological insulators became even more clear in 2016, when a team of scientists was awarded the Nobel Prize for its work on topological materials that “could be used in new generations of electronics and superconductors, or in future quantum computers.”

The microtubules’ ability to store energy on the outside of their structure, similar to a topological insulator, makes them a promising subject for future research, Prodan said.

Prodan said that physics has an important role to play in serving humanity, such as by assisting in drug discovery and helping run the communication technology behind programs such as Zoom.

Helping to Enhance STEM Efforts

Prodan said that she was drawn to Fordham because of the University’s expanding STEM offerings, particularly in physics.

That’s why she’s teaching an introductory physics course to undergraduates this summer. The hope is that students get excited about STEM at the beginning of their time at Fordham, before moving on to upper-level courses.

Prodan said that her lab is currently under construction but hopes that it will be ready by the summer or sooner, which would allow her to provide hands-on learning and research opportunities to undergraduate students, as well as local high school students.

“If you want people to have a better life, a healthier life, a happier life, physics and STEM in general are really important,” she said.

“In general, the discoveries that happen in physics don’t have an impact right away. It’s a long-term impact, but they’re essential.

]]>So when Fordham ceased face-to-face instruction at 1 p.m. on Monday, March 9, due to the threat posed by the COVID-19 outbreak, faculty were faced with the challenge of providing quality instruction that was true to their mission of supporting students and continuing to foster their potential. On March 13, the decision to suspend face-to-face classes was extended through the end of the semester.

As they begin to deliver instruction remotely, faculty have turned to online tools such as Zoom, WebEx, Blackboard, and Google Hangouts to continue students’ education. And they have turned to each other for support, guidance, and tips.

Planning for the transition began in earnest during the last week of February, when Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, and Dennis Jacobs, Ph.D., provost and senior vice president for academic affairs, briefed members of the Faculty Senate at its monthly meeting on February 28. Administration officials had been monitoring the spread of the virus in China, and once a case had been reported in Washington state in January, they thought it might spread throughout the United States.

Jacobs said that at that time the University was already making plans to offer online instruction to students who’d been recalled from study abroad programs and who would need instruction while self-quarantining.

“That was the call to action, to say, ‘Let’s begin preparations,’” he said.

“No one would have chosen this as a normal transition path, but these are extraordinary times, and our options were limited,” he said.

“Everyone was committed to serving our students and allowing them to progress towards their academic degrees. It was not just an option to shut down the campus, we had to come up with a continuity plan.”

Technology and Pedagogy

Making the transition required overcoming challenges both technical and pedagogical. Steven D’Agustino, Ph.D., Fordham’s director of online learning, is helping faculty figure out how to best use that technology to deliver their coursework. He’s offered videos and documentation on the University’s Official Online Learning Page and his blog, Learning at a Distance.

D’Agustino said he was impressed at how seriously faculty have put students’ well-being and peace of mind first and foremost. Many are using this week, which happens to be spring break, to explain to their students how they plan to move forward with the rest of the semester and taking steps like telling them exactly what times of the day they’ll be checking their emails. Faculty are establishing virtual office hours when they’ll be available for in-person consultation, and giving serious thought to whether future classes should be held synchronously, when everyone meets together, or asynchronously, which enables students to access material on their own schedules.

D’Agustino encouraged faculty to evaluate their methods as they go, and to draw on the experiences of peers across the country who face the same situation.

“I would say reflective practice is really valuable. This about what you’re doing, and reflect upon it after you’ve done it, and try to include your students and your colleagues in those reflective spaces. Because I think there are a lot of good ideas and support out there, and we’re not alone.”

A Quick Turnaround

Eve Keller, Ph.D., professor of English and president of the Faculty Senate, said she was astonished at how quickly faculty, who teach nearly 2,000 courses a semester, were able to work together to make the transition.

“Faculty had 36 hours to convert their classes online. Some people have done this, and some people had never heard of Zoom, but from what I’ve seen, it’s been an unequivocally congenial, collegial effort to make it happen,” she said.

The transition has not been without occasional hiccups. Anne Fernald, Ph.D., a professor of English and special adviser to the provost for faculty development, emailed fellow arts and science faculty for thoughts on pedagogy on March 11, and after receiving 20 replies, she felt prepared.

Still, when she attempted to teach her first class on Thursday with WebX, she didn’t realize the program’s default volume setting for the program is mute. She ended up recording a podcast for it with the information she planned to share, and is confident she’ll be able to make it work next week, when spring break ends and classes resume.

“I felt like the University did everything it could in this emergency to support us. And I think that the decision to be closed on Tuesday and give people time to prepare was huge. I had colleagues all around the country who didn’t have anything like that. Fordham did it in a way that was as compassionate as it could be,” she said.

Striking the Right Balance

On March 12, Mark Conrad, an associate professor of law and ethics at the Gabelli School of Business, taught three courses—Legal Framework of Business, Sports Law, and Law and the Arts—using the Zoom platform, and was happy with how it came together.

“I’ve been pleasantly surprised at how easy and accessible it has been. I had a number of questions from students. I wasn’t just talking to a computer,” he said, noting the ease in which he was able to share power point slides with students.

“We’re seeing future possibilities. It deals with something I’ve been thinking about which is, let’s say the professor is ill or has a sprained ankle. One could do classes like this, and it could actually minimize absences.”

Nicholas Tampio, Ph.D., a professor of political science, taught two classes on March 11 using WebX seminar after department chair Robert Hume, Ph.D., arranged practice sessions for the department. While they went off without a hitch, he said it was hard to read the mood of a room, as many nonverbal communication cues were lost in translation.

“When you teach online, you can’t see feet shifting, or if they have another browser open where they’re checking email. Their parents could be in the room, there could be a car going by. It’s not a controlled environment in which students are only there for the experience,” he said.

“I think I’m going to get better over time at being able to call on people, and I think I’m going to get better at organizing my slide show to make it more entertaining,” he said. But he acknowledged that face-to-face learning will always be preferable.

Edward Cahill, Ph.D., a professor of English, had never used Google Hangouts before and turned to it to teach Shakespeare’s sonnets and John Milton’s Paradise Lost. He found it to be similar to the normal classroom experience, although he said he plans to try different approaches to keep things interesting when the semester resumes, including splitting the class into both synchronous and asynchronous sessions.

Cahill’s new familiarity with online learning comes not only from his work as a professor, but also a student. His experience as a student in an entry-level Spanish class taught by Guillermo Severiche has given him hope that success is possible in the online realm, he said. Severiche, an instructor in the department of modern languages, moved their class to Zoom as well.

“We share documents, we used the e-textbooks. He managed the whole thing flawlessly. So that inspired me to think maybe I can do more.”

Cahill noted that he’s trying to be mindful of the challenges inherent in asking students to complete studies in the midst of a worldwide pandemic.

“There are so many balances to strike between rigor and flexibility, generosity and intensity. I don’t know that anyone has figured it out, and I guess as long as we can stay alert to all of those tensions, we’ll probably find our way through it,” he said.

Doing Lab Work Without the Lab

In some fields, resuming instruction is trickier than just establishing online connections. Stefanie Bubnis, interim managing director of the Fordham Theatre Program, said that while mainstage productions have halted, faculty have bolstered instruction on Google Hangouts and Zoom with old fashioned phone calls and FaceTime.

Professors such as Ann Hamilton, an adjunct professor of theater, are learning on the fly as well. For her first online Acting for the Camera class, she asked students to upload the scenes they recorded of themselves to Hightail and Google Drive. She watched the videos during the designated class time and wrote feedback in a group email to the 17 students in the class. Ultimately it proved to be too time-consuming.

“For my next class I intend to use Zoom, so we are all conferencing together, but they will have sent me the recorded auditions first, so I can have them up on my desktop and we can all watch them together at the same time and actively participate in the feedback. I think the students felt as if they learned a lot today, so that’s a win, given the circumstances,” she said.

Stephen Holler, Ph.D., an associate professor of physics, was able to move the lecture for his General Physics 2 class exclusively to Blackboard, but that wasn’t an option for Experimental Techniques for Physics, a course where teams of students had been working on a single project all semester.

“Some of the work, they’re in the machine shop, they’re doing 3D printing, they’re doing electronics,” he said, noting that this work will have to be completed in a different way than planned.

“Since they’ve done half the project, and they’ve already written up progress reports, I’ll have them turn those progress reports into a paper. Normally I’d also have them do a presentation on a research project they’re interested in; instead I’ll have them write a short paper on that and we’ll do Zoom presentations.

A Big Shift for Information Technology

For Fordham IT, the switch required an unusually speedy response.

Alan Cafferkey, director of faculty technology services, noted that his team—which includes experienced technicians, a fine arts and digital humanities professional, instructional designers, a former math teacher, a librarian, adjunct professors, a media and accessibility expert, and an Ed.D. candidate—normally prefers to work with six months lead time to develop an online course.

“This, however, was everyone already two months into the semester with only a couple of weeks of realizing that something might happen, prepping, and then a sudden shift, with hundreds of people making the change,” he said.

He was especially proud that his team was so on top of responding to the multitude of individual faculty requests. In addition, in collaboration with the provost’s office, they created a Course Continuity site before the University shifted to online learning—as preparation for what might happen.

When the switch was made, IT as a whole simultaneously shifted its entire operation to function remotely—including the IT Customer Care help desk—while helping other offices do the same.

IT also rolled out an entirely new enterprise-wide system in Zoom, reinforced numerous systems, and conducted a multitude of workshops on topics such as teaching synchronously and asynchronously, setting up remote offices, and best practices for many popular web tools. Additional workshops will continue through the spring and can be found on the department’s blog.

Going forward, Cafferkey said the department will continue to field faculty questions and requests, work closely with vendors such as Blackboard, and support other University initiatives as needed. He credited the efforts of colleagues across IT, the provost’s office, the IT departments in the Gabelli School of Business and Fordham Law, the online learning teams at the Graduate School of Social Service and the Graduate School of Education, and the staff at Fordham’s library.

“I’ve been really touched at how kind most of the faculty have been about the support provided. I’ve gotten so many thoughtful notes and comments, it’s been really heart-warming. It’s helped that there are so many offices working collaboratively,” he said.

Looking at the Big Picture

Lisa Holsberg, a Ph.D. candidate in theology, found herself transitioning Great Christian Hymns, which she is teaching for the School of Continuing and Professional Studies (PCS), entirely online. But she was in some ways already prepared to do so, as she is also currently teaching an online course, Christian Mystical Texts, for PCS. She was already accustomed to using Blackboard extensively, as well as Screencast-O-Matic and Voicethread, which lets students listen to each other talk, in their own words, about a specific problem. But ultimately, technology is just one little piece of the story, she said.

“It’s really, what is your commitment to students and to learning and going forward in the midst of change? How do you rethink what it means to teach, what it means to learn in conditions you’re not used to? You have to really dig deep into what your fundamental commitments are to your teaching, your students, to yourself, to your topic, and then just use whatever tools you have in order to meet those goals,” she said.

The Path Forward

Going forward, D’Agustino said he thinks faculty will settle into a hybrid approach for the rest of the semester, making tweaks as they get feedback from students.

“They may say, ‘We’re going to do a synchronous session, so here are the slides in advance, here is the reading material, here’s the study guide, there are some questions you should be able to answer during the session,’” he said.

“So even if a student can’t attend or log in, they still have the notes, the readings, the study guides, and they can say, ‘Professor I couldn’t log in; its 4 a.m. for me. But here are the answers to those questions. And the faculty member can, if it’s part of their protocol, share those answers with the class so that student is part of it.”

Jacobs said that he’s hopeful that faculty will rise to the challenge in what is an extraordinary time of upheaval. He noted that online instruction will always have a place in graduate level and professional-oriented instruction, especially for students who are working or have family obligations. As such, the University will continue to evaluate it on a case-by-case basis. But face-to-face teaching and learning is at the heart of Fordham’s mission, he said.

“Jesuit education is really one of formation in context of community. We treasure that at Fordham, and we always will. It’s the reason why during the academic year, we have not, by intention, moved our undergraduate academic offerings into an online format. We’ve offered them face-to-face, and will return to that when it safe to do, when the virus has passed,” he said.

]]>

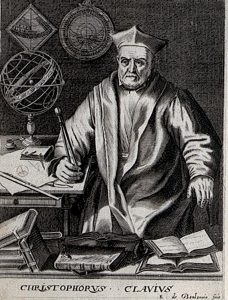

Titled, “Comets, Craters, and Calendars,” the lecture celebrated the 480th anniversary of the birth of the great mathematician and astronomer Christopher Clavius, S.J. Father Mueller is the vice director of the Vatican Observatory and superior to its Jesuit communities in Rome and Arizona. Following the talk, a panel of Fordham mathematicians and scientists shared how Clavius influenced their lives and work.

Champion of Mathematics

For the lecture, Father Mueller took listeners on a tour through the history of a man who, among his many accomplishments, is perhaps most noted for championing and helping design the Gregorian calendar that is still in use today. But the calendar, famous as it may be, was not the primary focus of Father Mueller’s talk. Instead he equated the scene from 2001 to Clavius’ championing of mathematics.

“In my view, Clavius played a historical role somewhat akin to that of Kubrik’s monolith: Through his teaching and textbooks and curricular reform, Clavius was the midwife of one of humanity’s great leaps forward: the scientific revolution,” he said.

Father Mueller was careful to point out that Clavius, who was born in Bamberg, Germany, may not have played an “active first-person role in the scientific revolution of the first half of the 17th century,” as he died in 1612. But through his many years of teaching at the Jesuit Roman College and through the wide use of his textbooks on mathematics and astronomy, Clavius greatly influenced the innovators and discoverers. He also “amplified” the importance of mathematics at universities, Father Mueller said, which theretofore had been taught at the 16th-century equivalence of high-school level.

“In the 16th-century curriculum, mathematics did not have the high status of a science,” he said. “A science was understood to be a discipline capable of knowledge of true causes. Mathematics was held to deal not in true causes but in mere abstractions—in mere possibility rather than reality. Mathematics teachers and faculty members were seen as being of lower status—they didn’t have much of a say.”

Forming a Pedagogy

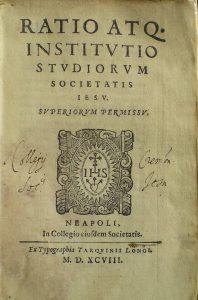

Having joined the Jesuits in 1555, Clavius was received into the order by St. Ignatius himself, placing him amidst the “explosive growth” of the young order and its ever-expanding roster of Jesuit schools. Near the time of Clavius’ death there were 372 Jesuit schools that would have been the equivalent of junior colleges today. Even outside of the Jesuit institutions, from the 1580s to the 1640s “just about everyone got their introduction to math and astronomy from textbooks written by Clavius,” said Father Mueller.

Father Mueller noted a few examples of Clavius’ fame, which he cemented through his role as the official public explainer and defender of the calendar. As a young professor, Galileo relied on lecture notes obtained from Clavius’ math and astronomy class, which led him to conclude Clavius “worthy of immortal fame.” During Clavius’ own lifetime he was known as “the Euclid of our Time.” And at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, there are only two Jesuits who are portrayed: St. Ignatius of Loyola and Clavius, who can be found on the tomb of Pope Gregory XIII, presenting the new calendar.

In Part VI of his Constitutions for the Society of Jesus, St. Ignatius called for a separate document to provide guidance for Jesuits schools. That “separate treatise” eventually became the famous Ratio studiorum of 1599, and Clavius held significant sway in its treatment of mathematics, said Father Mueller.

“An earlier 1591 draft of the Ratio includes an admonition to university administrators to make sure that philosophy teachers do not disparage the dignity of mathematics,” he said. “In a document written as a contribution to preparing the Ratio, Clavius wrote: ‘Since … the mathematical disciplines in fact require, delight in, and honor truth… there can be no doubt that they must be conceded the first place among all the other sciences.’”

Post-Lecture Q&A

Father Mueller said that both the new Gregorian calendar and Clavius’ proposals for an augmented role for mathematics in the curriculum met with significant resistance, and in both cases Clavius took on a “prominent role as explainer and defender”—of the “validity of the calendar and of the dignity and worth of mathematics as a path to objective truth.” It’s a role that resonates to this day, with science and truth under attack at the highest levels of government and religion. In a conversation after the lecture, Father Mueller drew parallels between Clavius’ role and that of contemporary Jesuit institutions.

In your talk, you noted that at the time of his death Clavius had not finished publishing his theory of astronomy. It sounds like he was very cautious with the truth.

At the end of his life, he mentions in a letter to one of his colleagues that he’s in the middle of writing a theory of astronomy, but he also mentions explicitly that he’s waiting for more data from [Danish astronomer] Tycho Brahe, to help him know what he wants to do. He never ended up publishing it in his lifetime. I personally think what happened was he saw that astronomy was changing so rapidly, the time was not right to write a theory.

Last spring’s Clavius lecture dealt with artificial intelligence. Things are moving so quickly in that sphere that peer-reviewed articles are almost an impossibility. What would Clavius make of that?

Be careful about imposing the whole notion of peer review back on him. His time is where the whole idea that empirical observation of the heavens can affect astronomical theory. That itself is a new idea. You knew your astronomical theories from ancient authorities. That’s part of what got Galileo in trouble, but I think Clavius was doing it more cautiously. The whole thing with Galileo blew up after Clavius died, so he had no notion that there was theological danger. But, I think, as a teacher, he didn’t want to go in print with a textbook with stuff that’s not right. In the late 1500s there was an extraordinary series of comets and novas in the heavens, which really wowed people because physics at the time said that the heavens should be immutable and unchanging. Clavius participated in proving this stuff shouldn’t be changing. So, I think that’s part of what slowed him down. He says at one point, ‘Maybe we need to rethink at a fundamental level, our astronomy.’ Today, we all agree what the standards are. Clavius was in a time when the very notion of standards themselves were changing.

Clavius had the ability to speak to the public and the men in power to convince them of truth and the importance of empirical standards. What lesson we can draw from that today?

Clavius had to explain and defend. I hope I don’t sound too despairing here, but he lived in a time when everyone knew and believed that there was such a thing as an objective truth. They might have disagreed about how to get there, the standards were changing, but no one disagreed that there is objective truth. We are now in a very strange time, a new time, where for many reasons, people’s confidence in the very notion of objective truth has been shaken. And, I find that to be a really dangerous and a sad step backwards. … I’m very discouraged by the fact that, as a culture, we seem to be backing away from the notion that we’re capable of coming to agreement on objective truth. It’s hard, you’ve got to work at it, you’ve got to be willing to fight, but there’s a truth out there.

Yet so much of the recent challenges to science come from people of faith. How do you, as a Jesuit, deepen your faith in light of scientific truths?

My colleague at the observatory, Guy Consolmagno [S.J.], is always clear in saying that when he does science, for him it’s an act of worship. If God is the way, the truth, and the life, then when you look for the truth via science, you are also looking for God. I believe that the very search for truth means that I trust that my reason participates in God’s reason. I’m made in God’s image and I really think that matters. We really need to work together to come to some kind of agreement on these things, because it’s a great, lovely mystery that should bring us together.

Bill Breisky recalls his grandfather Victor Hess, who discovered cosmic radiation 100 years ago and spent more than a quarter-century teaching physics and conducting research at Fordham.

Victor Francis Hess and I inhabited different worlds. He was born in the green heart of Austria and schooled in physics and mathematics in its Renaissance capital, Graz. I was born in the smoky city of Pittsburgh and schooled in the very unscientific world of journalism.

And yet, we shared common ground. Both of us loved searching for truth and unraveling mysteries (we shared a passion for Eric Ambler spy novels), and of course we loved Grandma Hess and her incomparable dumplings and strudels. She had married Victor two years after her first husband, Artur Breisky, a retired major in the Austro-Hungarian army, died during the First World War.

I first set eyes on my Austrian grandparents in Innsbruck in mid-1932, in the heart of the Great Depression. The Hesses had offered to share their apartment there after my father lost his job in Pittsburgh and suffered a nervous breakdown. I was almost 4 years old at the time, and my brother Arthur was an infant. His howling became an issue for grandma—or “Ma-ma,” as she was called. She demanded peace and quiet so that her husband the professor, my step-grandfather, could concentrate on his papers and have an afternoon nap.

It was a tumultuous year for both families, with young Nazis, the Heimwehr, and Bolsheviks clashing in the streets “right outside our window,” my mother reported in a letter home. But there were many good times, one of them a visit to the new cosmic radiation observatory Victor Hess had established one year earlier on Mount Hafelekar, outside of Innsbruck. My mother wrote in the Hafelekar guest book: “The top of the morning, and the top of the world!” She signed it, “Laura Breisky and Billy, Pittsburgh, Pa., U.S.A.”

Two years later, back in Pittsburgh, Laura Baer Breisky died of breast cancer.

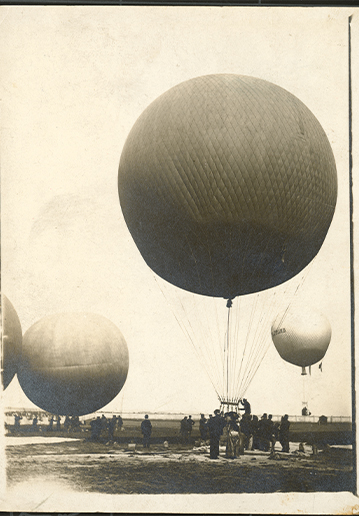

We were still in Pittsburgh in 1936 when we received a telegram from Innsbruck informing us that Victor Hess was, belatedly, to be awarded a Nobel Prize in physics for his discovery of cosmic radiation during the daring experiments he had conducted while aloft in a balloon more than two decades earlier. To celebrate, the Hesses sent my brother and me garments that were a source of amusement at the Pittsburgh school I attended—lederhosen.

By 1938, we had moved to Baltimore, and Hitler had moved into Austria. Fascist-dominated Europe was already in the midst of a great intellectual and cultural migration to America—Einstein, Pauli, Fermi, Stravinsky, Chagall—but the Anschluss hastened the process, and Austrians became the second largest national group in that migration. One writer called these emigrants “Hitler’s gift to America.”

Victor Hess, thanks to the Nazis—who dominated the faculty at the University of Graz—was made virtually penniless when he fled with my grandmother to Switzerland, having been forced to leave behind the Swedish crowns that had come with his Nobel award. The Nazis had declared grandma to be Jewish (she had converted to Catholicism but was irreligious) and grandpa to be “too cosmopolitan” (he had served as a science representative in Austria’s democratic government). But news of his plight spread rapidly, and he soon received the offer of a full professorship from Fordham University.

The Hesses spent Christmas with us in Baltimore that year, and I began a bond with my grandfather—one that lasted until his death, 26 Christmases later.

In 1943, I contracted double pneumonia, was hospitalized for eight weeks (penicillin had not yet been discovered), and recuperated with the Hesses for the summer at their apartment on William Street, in the Fleetwood section of Mount Vernon, New York. I had received the last rites of the Anglican church while in the hospital, and that prompted grandpa to tell me of his deep religious faith, and of the vow he had made after larynx-cancer surgery had left him with a voice that never rose above a hoarse whisper. He said he had vowed that if he were spared, he would attend Mass faithfully for the remainder of his life. He kept that vow.

“A scientist, more than other scholars,” he wrote during his first decade in America, “spends his time observing nature. It is his task to help unravel the mysteries of nature. He comes to marvel at these mysteries. Hence it is not hard for a scientist to admire the greatness of the Creator of nature. From this it is only a step to adore God.”

He took me to Mass on several Sundays after that. And to a movie, preferably one featuring Humphrey Bogart or James Cagney, on afternoons when he drove grandma to one of her bridge games. Grandpa and I cheered for the Yankees at Yankee Stadium, and we marveled at Pancho Segura’s two-handed swing in the Davis Cup tennis tournament. I learned that Victor Hess had been an avid tennis player as a young man.

I never saw my grandfather in tennis shorts, however. His day-to-day uniform was a three-piece Witty Brothers suit—or at least shirt, suspenders, trousers, and a vest. He required a vest with pockets ample enough to hold his gold pocket watch and chain, a packet of Chiclets chewing gum, a pen, and a small notebook, where a meticulous record of his expenses was recorded in a daily diary.

Victor Hess’ intellectual home in America was, of course, at Fordham—his laboratory, office, and lecture hall. One corner of his spacious office seemed reserved for instrumentation, to monitor the weather and measure breath samples with his good friend and colleague William McNiff, Ph.D. He and Professor McNiff developed a method of measuring small amounts of radium in the human body.

When I visited grandpa at Fordham as a boy, we would share lunch on a campus bench or at a Fordham Road restaurant that served an excellent fillet of sole for 40 cents. Those lunches often were followed by an afternoon of taking measurements—at times on a Harlem River pier where we tossed bits of raw sodium into the river and laughed at their explosive sizzle. He took me to the Empire State Building, where he and a colleague had taken measurements of radioactive fallout after Hiroshima. (He was appalled at the idea of nuclear testing after the war.) And a couple of times, I accompanied him to the 190th Street subway station beneath Fort Tryon, where he had obtained permission from the city to measure radiation in a granite wall some 400 feet below the surface.

I sat in on what I believe was his final lecture on the Rose Hill campus. He told his students that he had loved every class he had taught at Fordham.

Last year, I located one of his prize doctoral students from that time, Joseph Braddock, Ph.D., GSAS ’59. Braddock and two other physicists who studied under Hess while earning their doctorates left Fordham in 1959 to create the defense and technology contracting firm of Braddock, Dunn and McDonald, which went on to play a major role in the development of American anti-missile technology.

“My strongest memory of him is as a great lecturer—and a great listener,” Braddock said. “Often Bernie Dunn, Doctor Hess, and I sat down and had lunch, in the office or in the lab, and talked, frequently about opera. The unofficial Victor Hess was very warm.”

Grandma Hess died of cancer in 1955, at home, where she had been nursed lovingly by Elizabeth Hoencke, a German refugee. Before she passed away, grandma gave one final instruction to Victor: “Marry Elizabeth.”

Several months later, Victor did as he had been told. Elizabeth called her bridegroom “mein Schatz.” She accompanied him to Rome, when he was inducted into the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and to the White House to attend a dinner for Nobel laureates hosted by Jack and Jackie Kennedy.

Late in 1964, Victor was confined to a hospital bed in his living room. A week before Christmas, Elizabeth called our home in Connecticut to tell me, through her tears, that Parkinson’s and pneumonia had finally prevailed, and that her Victor had died.

Grandpa’s funeral, in Mount Vernon, was very small. I recall that a few Fordham Jesuits were there, along with Elizabeth’s family, but not many others. He seemed virtually forgotten, and that pained me. Grandpa Hess was buried in White Plains and gone from our lives, except in my memory.

Or so I thought.

In the fall of 2007, I underwent a procedure called proton-beam stereotactic radiosurgery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. A neurosurgeon targeted my cerebellum with high-energy protons that halted the growth of a benign tumor. Afterward, I asked the medical physicist who had worked alongside the neurosurgeon whether she had ever heard of a physicist named Victor Hess.

“Of course,” she replied, stunning with me with the news (it was news to me) that an observatory called H.E.S.S., or High Energy Stereoscopic System, had been established in Namibia to search the skies for the origin of cosmic rays. Another physicist at the hospital told me that the development of the particle accelerators that had made my radiosurgery possible was stimulated in large part by my grandfather’s balloon-flight discoveries.

In 2009, Grandpa Hess came alive for me yet again when my wife, my brother, and I visited the University of Vienna. I sat at grandpa’s old roll-top desk and examined the instrumentation he had devised for his historic 1912 balloon flights. And we met Professor Peter Schuster, who had been instrumental in establishing the Victor Franz Hess Society—in order, as he put it, “to bring him home to Austria, from which the Nazi regime had banished him, and to be once again the figurehead of Austrian physics we have been missing for too long.”

To my son John and my teenage grandson Ethan McPherson, Victor Francis Hess was a family legend and the subject of a gray photograph that hangs in my study—a stout, young mustachioed man in a three-piece suit, standing in the basket of a hot-air balloon. It seemed high time that they got to know Grandpa Hess better, so in the last week of May 2011, we paid our respects to the Rose Hill campus.

Our first stop was Freeman Hall. The Hess lab was gone, but there were countless reminders of him in the office of physics Professor Martin Sanzari, Ph.D., head of Fordham’s new engineering physics program. Sanzari had organized Victor Francis Hess Day earlier this year. We chuckled at a photo of an exuberant student wearing a T-shirt proclaiming, “Victor Hess Day is the Bess Day!” And we paused reflectively in Freeman’s lecture hall—so unchanged that I imagined I could find the seat I occupied on the last day that Victor Hess formally addressed his students.

The Arthur Avenue restaurant where we had lunch was recommended by none other than Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, who had warmly welcomed us into his office in late morning. Father McShane saw to it that John, Ethan, and I were outfitted with maroon Fordham caps before ushering us to the Administration Building’s Hall of Honor, where a Victor Hess plaque shares wall space with none other than Bronx-born baseball legend Frankie (“The Fordham Flash”) Frisch. Father McShane’s parting words to Ethan: “I’ll see you in four years.”

It was in the archives of Fordham’s William D. Walsh Family Library that the spirit of Victor Hess seemed most alive. In its stacks were copies of some of his letters to old colleagues who had made their way out of Nazi-occupied Europe to the United States—Swiss biologist Eugster on 54th Street in Manhattan, Austrian Nobel laureate Loewi on 93rd, Austrian ex-Chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg in St. Louis, among others.

We found a 1950 paper written by Hess the motoring adventurer on “The Capacity of a Highway.” (A maximum number of vehicles can travel safely and efficiently on a highway, he calculated, if they maintain a speed of 15 miles per hour.) And an astonishing discovery—the tattered address book he had kept atop his desk in Fleetwood containing the addresses of physicist Georg von Hevesy, his old balloonist companion; of Fordham colleagues McNiff, Weber, and Kovach; and, to be sure, those of prize students Braddock, Dunn, and McDonald.

Grandpa Hess would be surprised to learn that records of his work occupy 34 cubic feet in Fordham’s archives. He also would be surprised to find more women than men walking the Rose Hill campus. And I’m guessing that he would be pleasantly surprised that solar panels and a wind turbine are planned for the roof of Freeman Hall—while, as my son John the architect observed, the green and leafy Gothic-style campus appears virtually changeless, despite all its well-concealed modernization. A place of faith and reason, and beauty.

Ethan, who’s in ninth grade (my age in the middle of my Fordham-visiting years) googled Victor Francis Hess when he got home and promptly advised us, “He died on December 17. That’s my birthday!” Should I have been surprised? Grandpa Hess lives on.

Next August, Victor Hess will be remembered throughout the world as the scientific explorer who, 100 years earlier, made a series of historic flights—in what essentially was a flying basket—to demonstrate the existence of cosmic radiation. He will be remembered for his enduring love of nature, for his exploration of nature, and for his love of the Creator of nature.

He will also be remembered, by me, as the person who signed his letters, “Your loving Grandpa.”

—Bill Breisky is a former associate editor of The Saturday Evening Post. From 1978 to 1995, he was the editor of the Cape Cod Times.

]]>One hundred years ago, on Aug. 28, 1911, Victor Hess took to the skies in a hot-air balloon to begin the work that would earn him a Nobel Prize in Physics.

At the time, scientists were puzzled by the fact that the air in electroscopes (instruments used to detect electrical charges) would often become electrically charged no matter how well the containers were insulated. Most physicists believed radioactivity from ground minerals was responsible for this. They suspected that the ionization levels in the atmoshere would diminish greatly at higher altitudes.

Enter a Jesuit scientist. In 1910, Theodor Wulf, S.J., measured ionization at the bottom and top of the Eiffel Tower in Paris. He found that ionization levels were puzzlingly higher at the top of the tower, some 300 meters above ground. But his results were not given unqualified acceptance by the scientific community, nor were the experiments of other scientists who made balloon ascents to record ionization. Their instruments developed defects at high altitudes, casting doubt on their measurements.

Victor Hess, a postdoctoral student at the University of Vienna, was in his late 20s, an accomplished balloonist, a dedicated scientist and an adventurous spirit. He had read about Father Wulf’s experiments and speculated that the main source of radiation could be located in the atmosphere rather than in the Earth.

But before he took to the skies, he did two key things: He determined the height at which ground radiation should stop producing ionization (approximately 500 meters), and he designed his instruments so they would not be damaged by temperature or pressure changes as he went up in his balloon. He then made 10 daring ascents—two in 1911, seven in 1912 and one in 1913—rising to more than 17,000 feet above ground to take his measurements.

What Hess found confirmed Father Wulf’s measurements. The radiation levels increased the higher he climbed. In fact, Hess found that the ionization rate increased approximately fourfold over the rate on the ground. He interpreted these results to mean that radiation enters the atmosphere from outer space.

We now know that cosmic rays are actually high-energy particles that flow into our solar system from far away in the galaxy. But at the time, of course, no one really believed radiation could be coming from a celestial source. Hess had ruled out the sun as the source of the radiation, as he made several of his balloon ascents at night and one during a total eclipse.

“The results of my observation,” he concluded, “are best explained by the assumption that a radiation of a very great penetrating power enters our atmosphere from above.”

This was the discovery that would earn him a 1936 Nobel Prize in Physics. Two years later, Hess arrived at Fordham. In his lab in Freeman Hall, he helped develop a method for detecting minute traces of radium in the body. A company hired him to test its radium-dial workers—women who hand-painted watch dials so that the faces would glow at night. It was probably some of the first environmental testing of its kind in the workplace.

In 1958, Laurence J. McGinley, S.J., president of Fordham, presented Hess with the University’s highest honor, the Fordham University Insignis Medal.

“He has ever been zealous to develop in his students the love of research and the tireless dedication to it which have always marked his life,” the citation reads. “Both as explorer of the secrets God has hidden in nature, and as interpreter of those secrets to his students and to the world, Professor Hess has given a notable example of how the curiosity of the true scientist and the faith of the devout Catholic can dwell harmoniously under one roof.”

—Martin A. Sanzari, Ph.D., Assistant Professor and Director of the Engineering Physics Program, Fordham University

]]>