The panel is an independent advisory body that synthesizes scientific information on climate change. Members advise city policymakers on local resilience and adaptation strategies that protect against extreme heat, heavy rain, coastal storm surges, and other climate hazards.

“Much of New York City comprises islands. We must be prepared for the fact that we’re at risk of future hurricane landfall, we’re going to lose land to sea-level rise, and there will also be drought and temperature increases,” said Conte.

“I’m very excited to contribute knowledge that can be put to good use for a panel like this.”

Conte is the first Fordham professor to join the panel, which was first formed in 2009 and renews its membership every three years, tapping experts from government, non-profits, and academia. This appointment is not the first time the government has called on Conte for his expertise; his research on climate change was cited in a major report issued by the White House.

Learning from Past Climate Disasters

Each new panel is tasked with issuing a report at the end of its three-year term. Conte said that past panels have analyzed global climate models that had been recently released, downscaling them to show how they might affect New York City.

No new models have been released recently, so he said he expects this panel will dig deeper into the challenges that are already known–particularly those highlighted by recent disasters. The group will hold a series of public meetings this year to gauge the public’s interest in specific areas.

Conte said the panel will provide important guidance during a critical time.

“Given the outcome of the recent election, we expect that federal leadership in this area is going to be greatly diminished,” he said.

“New York City is a high profile area, so this kind of assessment is important to maintain the focus on the challenges we face and show what can happen at the local level to reduce the impacts of climate change.”

Recent examples of extreme weather worth re-examining are numerous. Conte said the panel may determine what will happen to water supplies if droughts like the one that lasted nearly a month continue. Or it might try to quantify the risks that New Yorkers will be exposed to as a result of extreme bad air days caused by Canadian wildfires or those posed by brush fires that have been on the rise in the New York City area.

“We’re also thinking about when the next Superstorm Sandy is going to come through and how we’ll have to deal with it,” he said.

Conte, who has published research on outdoor air pollution in New York City, the challenges of managing tropical cyclone risk, and the impact of climate change on natural capital, hopes the panel will explore each of these topics.

The Everyday Costs of Climate Change

He’s also hopeful that as an economist, he’ll be able to help the panel illustrate the societal costs of climate change and pollution that are poorly understood by the general public.

“One of the big challenges is that, as we just saw in this election, everyone cares about the price of milk, but we don’t have a price for clean air or a price for not having to miss work because of asthma or because it’s too hot,” he said.

“I’m hoping to provide literature that shows what types of policy interventions are successful when facing these challenges and what the difficulties are for policymakers in putting them into action.”

]]>That’s according to a study co-authored by Fordham economics professor Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., and researchers in health-related fields at other universities. It shows that after four decades in which inflation stayed low and didn’t pose a serious problem in America, the mental health impacts of its spike in the past few years are ripe for study, Mitra said.

“That’s an open field in terms of research,” she said. “We know … that unemployment has very detrimental effects on mental health, and that a job loss can lead to depression and other negative mental health outcomes.” Inflation has received less study, but seems to be “a very important potential determinant of well-being, including mental health,” she said.

The study also suggests that positive economic news, like a low unemployment rate, may be “insufficient in terms of telling us about how people feel about the economy,” she said.

The High Price of Milk

The study, based on data about 71,000 working-age adults, was published earlier this year in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. The researchers used information from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, begun during the coronavirus pandemic, which collects data about how households are affected by various social and economic issues.

Their study focused on respondents who told the Census Bureau about their stress level caused by price increases. It compared these stress levels in mid-September 2022, when the inflation rate was 8.2%, with levels in June 2023, when inflation had dropped to the closer-to-normal rate of 3%. Despite the decline, the share of respondents who were very or moderately stressed by inflation increased, going from 77% to 79%.

The increase, Mitra said, suggests that a short-term measurement like the inflation rate might not reflect the cumulative stress caused by rising prices. People’s belt-tightening measures can include canceling subscriptions, cutting back on utilities, delaying medical treatments, and working additional jobs, the study notes.

And even if the inflation rate drops, prices are still “a lot higher than what they were a couple of years ago,” she said. “The price of a gallon of milk is not what it used to be in 2020.”

Impact of Job Losses, Long COVID

Mitra also noted that stress due to inflation is worse for those whose income is cut, whether from a job loss or a case of long COVID-19. Among other findings, the study found stress levels increased more among certain groups, including less educated adults and women in general, for instance.

The study calls for policies to address “the complexity of stress responses” stemming from societal challenges like the pandemic and the inflation that followed it—a combination of problems seen “never before in the history of the U.S.,” the study says. The study also points to the need for adding inflation adjustments to government benefits and tax credits—such as the child tax credit—that promote people’s economic security, Mitra said.

She looks forward to future studies with her cross-disciplinary group, which includes researchers from the social work school at Rutgers, the Penn State Cancer Institute, the University of North Texas Health Science Center, West Virginia University’s department of dental public health, and JPS Health Network in Fort Worth. “We share an interest [in]the relation between economic insecurity and health,” she said.

]]>The interdisciplinary degree will give students computational tools and techniques from the field of data science, as well as economic theory and statistical training from the field of economics.

“Many employers want students who can manage and analyze large data sets,” said Johanna L Francis, Ph.D., chair of the economics department.

While similar to the dual MA/MS program currently offered by the departments of Economics and Computer and Information Sciences, the new degree will be a single M.S. It will be offered by the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

Meeting Employer Demand

Francis said the degree was created to meet the employer demand for graduates with expertise in Python, a high-level, general-purpose programming language, and R, a programming language for statistical computing and data visualization.

“There’s software that you can use where you don’t need to have much programming experience, but many employers would prefer students who are able to at least code some of their own analysis.”

The degree, which is the first and only program of its kind currently available on the East Coast, will comprise 10 courses from the economics and data science departments, including three electives. Students will also complete a capstone, internship, or thesis.

Francis noted that economics is still a very traditional liberal arts degree that incorporates political science, history, and psychology but has become much more quantitative.

Data science offers skills that provide students with a much deeper understanding of algorithms, which is why the dual MA/MS Degree in Economics and Data Science program was first developed in 2021. While students who pursue the dual degree gain a deeper understanding of economic theory and computational methods while having the time and expertise to engage in research projects, this new degree combines the two disciplines even more seamlessly.

“This new degree allows students to do the degree in a year and a half, or a calendar year if they do summer courses, and it is much more intense than the dual degree,” she said.

Gaining a Competitive Edge

Yijun Zhao, Ph.D., associate professor of computer and information science and program director of the M.S. in Data Science program, said data science students will equally benefit from immersing themselves in the field of economics.

“For data science students looking for jobs, one of the major challenges is that they have the technical skills but lack the knowledge or language of a particular field,” she said.

“This degree will help data science students gain the necessary knowledge in economics, giving them a competitive edge.”

Francis said the emergence of AI large language models, or LLMs, has made the degree like even more valuable.

“Economics is a very analytic discipline with a basis in human behavior, and when you combine it with a knowledge of algorithms that are the backbone of LLMs, you give students a very solid background in problem-solving.”

To learn more, visit the program webpage.

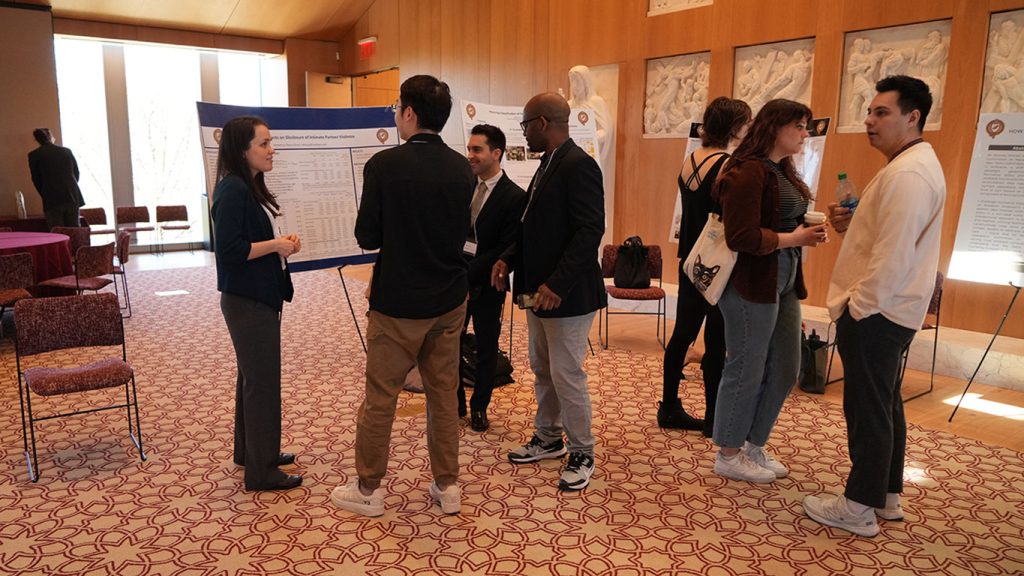

]]>“It’s really gratifying to see how many of the projects lean into our identity as a Jesuit institution,” said Ann Gaylin, dean of GSAS, “and strive to advance knowledge in the service of the greater good.”

Students displayed posters on topics that ranged from biology to theology to economics to psychology.

Nina Naghshineh, Ph.D. in Biological Sciences

Topic: The Role of Bacteria in Protecting Salamanders

How would you describe your research?

I study the salamander skin microbiome and how features of bacterial communities provide protection against a fungal pathogen that is decimating amphibian populations globally.

Why does this interest you?

I’m really interested in how microbes interact and function. My study system is this adorable amphibian, but the whole topic is so interesting because microbial communities are so complex and really hard to study. So the field provides many avenues for exploration. These types of associations are present in our guts and on our skin. I’m interested in going into human microbiome work after I graduate, so I have a lot of options available to me because of this research.

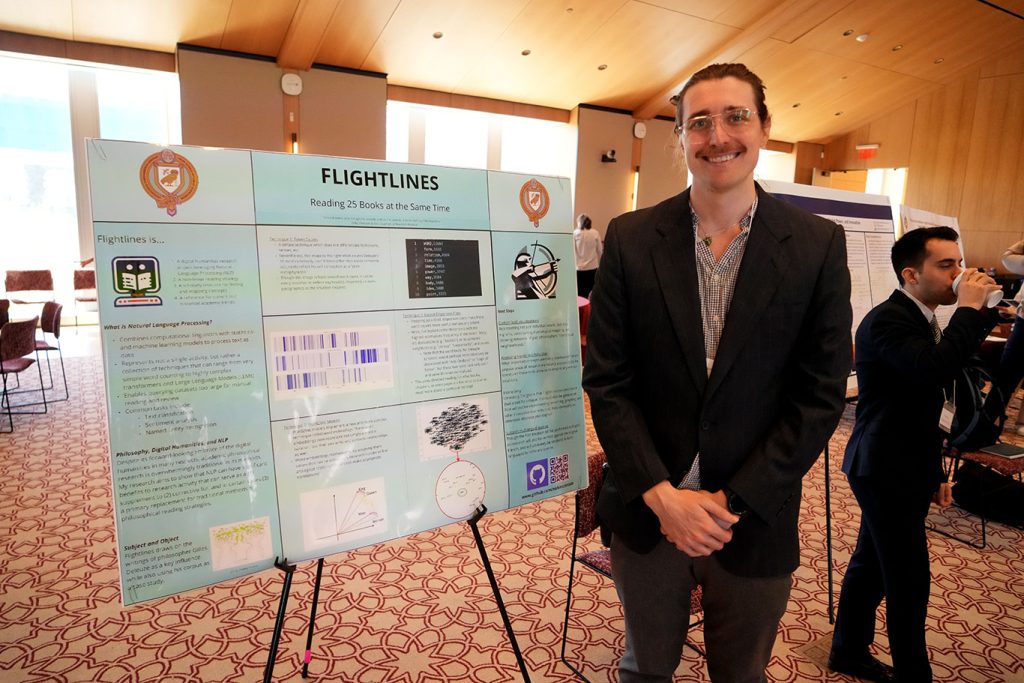

Nicholas McIntosh, Ph.D. in Philosophy

Topic: Using AI to Help Scholars Distill Information from a Vast Body of Texts

How would you describe your project?

It’s a digital humanities project that uses natural language processing to help read and understand many texts at once. There’s this vision we have of a really great humanities scholar who is able to know a text so well that they could almost quote it from memory. That is really difficult for us to do right now in the same way we might have when there were only a couple of touchstone classical texts.

What do you hope this will accomplish?

Scholars are scanning texts either for our classes or for our own research. So this would help us figure out, number one, how can you look at a text and be able to recognize— is this text useful for me? Number two, what are the most important concepts that we should be tracking in a text? And number three, what is the text as data telling us that maybe scholarship is overlooking or overemphasizing given traditional readings?

I would also like to show that those of us who do philosophy don’t have to be afraid of these technologies.

Angel Villamar, Siphesihle Sitole, and Virginia Scherer, M.A. in International Political and Economic Development (IPED)

Project name: Climate Mitigation: The Role of a People’s Organization in the Philippines

What were you investigating with this research?

We looked at the role of the grassroots organization Tulungan sa Kabuhayan ng Calawis in dealing with climate mitigation. It was formed after Typhoon Ketsana hit in 2009. There is an area right outside of Manila that, over the years, has been deforested, so this organization organized to help incentivize reforestation. The farmers in the area, who are mostly women, develop the seedlings, do the land preparation, and plant the trees.

What do you hope people learn from this project?

We want to think about reforestation not as a one-time thing but as a long-term sustainable way. What incentives do you need so that you can keep doing this? We are showing that you can involve ordinary individuals at the grassroots level in something that is much bigger than them.

During the COVID pandemic, a story in the New York Times caught the eye of economics professor Troy Tassier, Ph.D. Using anonymous cell phone data, researchers showed that nearly 50% of residents in New York City’s wealthiest communities had left the city.

Those in poorer communities stayed for the most part, working at in-person jobs and commuting along their normal bus and subway routes. As a result, Tassier said, in the first year of the pandemic, the rate of mortality in some of the hardest hit, poorer neighborhoods was five to six times higher than it was in affluent areas in New York City.

It inspired Tassier to produce research on herd immunity and other infection-related data. In February, he published The Rich Flee and the Poor Take the Bus: How Our Unequal Society Fails Us during Outbreaks (Johns Hopkins Press, 2024), which investigates how social inequality affects epidemic outbreaks.

The book examines pandemics from the past, from the Bubonic plague that devastated Hong Kong in the 19th century to the influenza pandemic that ravaged New York City in 1918. Why was it so important to highlight this history?

At the beginning of the pandemic, there was this narrative that this was a great equalizer, but I knew it wasn’t going to be true, just from past pandemics. In New York City in the 19th century, poor people were blamed for the pandemics because they were afflicted more than wealthy people. But it wasn’t their fault; it was the conditions that they were living in. During COVID-19, we were experiencing some of the same things.

Were you surprised by anything you encountered while doing your research?

The biggest surprise was just how similar past epidemics were to what happened in 2020, down to things like fights over masks. There’s a story from 1918 about a fight between a health inspector and a person standing on the street corner who was arguing with people, telling them they were fools to be wearing masks. They ended up in an altercation, and a couple of people were shot.

I have a cousin who lives in the South who was doing curbside pickup at a store in 2021, and she was accosted by two guys who tried to rip the mask off her face.

A major point of the book is that we should treat medicine as a social science. Do you think the pandemic made that clear to people?

No, and that’s one of my biggest disappointments. You still hear refrains coming from both the left and the right that public health needs to step away from proselytizing and just “follow the science,” but part of that science is how people are reacting to policies and to each other.

Something I’ve been grappling with is, last month the CDC eliminated the five-day isolation period following a positive infection. Now, these isolation periods are regressive because they harm working people who don’t have paid sick leave or might not be able to afford childcare if their child has to stay home to be isolated.

But the CDC shouldn’t be saying there’s a problem with the regressive nature of this five-day isolation; therefore, we need to get rid of the isolation period. What they should be saying is we have these problems in society, and we need to work to get rid of this inequality.

It’s not just as simple as people raising themselves up by the bootstraps.

]]>But was that air pollution actually causing those symptoms?

In a new study published this month, Marc Conte, Ph.D., professor of economics at Fordham, says no.

“There’s no question that air pollution is a public health threat, but measuring the impacts of air pollution on humans, whether it’s cognitive ability, physical health, or mental health, is pretty challenging,” said Conte.

Correlation vs. Cause

The challenge, he said, is overcoming the temptation to put more weight behind observational studies than they deserve. A researcher might collect data and determine that a large number of people with dementia have bad teeth. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that bad teeth cause dementia.

“The public health researchers who are conducting this work know that they’re studying correlations, but when the media reports on these studies, the layperson who consumes that information might not necessarily know that it’s a correlation and not causal,” he said.

For the study, “Observational studies generate misleading results about the health effects of air pollution: Evidence from chronic air pollution and COVID-19 outcomes,” which was published in the journal PLOS ONE, Conte and his research partners paired data from two different sources that were collected between March and September 2020.

The first source was health data gathered from U.S. Census tracts in New York City, whose geographic centers are less than 500 meters from a highway. That narrowed the number of tracts studied down to about 800 out of a total of 2,168 in New York City. The researchers then compared that to data collected from the New York City Community Air Survey, a network of 100 air quality monitors maintained around the five boroughs.

That extensive network, which augments a much smaller number of monitors in New York City maintained by the federal government, allowed researchers to compare communities that are downwind from highways with those that are upwind. If poor air quality were responsible for more severe COVID symptoms, communities downwind would be expected to fare worse than their upwind neighbors.

Findings

Conte said that across the 800 census tracts, there was no statistically significant difference between those who were downwind and thus had poorer air quality and those who were upwind and therefore had better air quality. Other factors, such as income differences, access to health care, and the ability to work remotely during the pandemic, are more likely culprits for severe symptoms, he said.

In addition, many residents in these areas were unable to leave New York City at the height of the pandemic, either because they lacked the means to do so, or their jobs required that they work in person. The inability to engage in this kind of “defensive behavior,” resulted in higher exposure to those infected with the virus.

“That fact suggests this issue of environmental justice extends beyond the fact that certain communities are located near more pollution sources,” he said.

“It’s actually a more systemic problem that lower-income people are employed in positions that could not accommodate remote work, with many designated ‘frontline’ workers,” he said, or simply didn’t have the resources to leave the city.

None of this means that researchers should cease conducting observational studies, especially during health emergencies like the pandemic, Conte said. Rather, he hopes the study will further elevate the notion that “correlation does not equal causation” in the public consciousness.

More Data = Better Outcomes

A second takeaway from the study is the importance of maintaining a large network of air quality monitors, which together are able to generate finely detailed data. In fact, Conte’s team also conducted a second experiment on the same topic using only data collected by the seven monitors maintained around New York City by the Environmental Protection Agency, without any input from the New York City Community Air Survey.

The results were much closer to the observational studies that had been done and might have led readers to believe that air pollution and severe COVID symptoms are explicitly linked to each other.

“As we think about things like wildfires and other sources of air pollution, these problems are becoming more and more intense,” said Conte.

“For us to be able to take measures that can reduce the public health outcomes and the threats to public health, we need to have more information. We need to invest more.”

]]>Published in the journal Nature, “Unequal Climate Impacts on Global Values of Natural Capital” reveals a staggering forecast: By the year 2100, 90% of climate change’s impact on vital ecosystems, including woodlands, grasslands, and other sources of economic benefits, will be shouldered by the poorest 50% of regions worldwide. These regions, Conte said, are more reliant on this “natural capital.”

“Humanity derives a lot of value from natural capital, and this value has been ignored in most models of optimal climate emissions,” said Conte, an associate professor of economics at Fordham who played a pivotal role as one of the co-authors of the research. The study, funded by a $750,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, was a collaborative effort with researchers from the University of California, Davis.

The implications of the findings extend beyond the scientific realm into global policymaking. “We’re allowing too many emissions, and we need to pay more attention to these impacts,” Conte emphasized, highlighting the urgent need to refine the framework used to determine acceptable greenhouse gas emissions.

To comprehend the impacts of greenhouse gasses on human well-being and national economies, Conte and his co-authors employed a sophisticated approach, using global vegetation models, climate models, and World Bank estimates. The study leveraged the World Bank’s wealth accounts to evaluate non-market ecosystem benefits, offering a standardized metric for comparison. The modeling allows more precise predictions.

“The World Bank’s values, although conservative in the scope of benefits included, provide a consistent approach to understanding the value of natural capital at the national level,” Conte said. “Our research takes this a step further by disaggregating a country’s total value of natural capital and distributing it across different ecosystems within its borders.”

Beyond the scientific discoveries, the research raises ethical and policy considerations of global significance. Conte highlighted the responsibility of wealthier nations to recognize and address the disproportionate impact of climate change on less affluent regions, emphasizing that climate change is not merely an environmental concern but a profound economic and social issue.

“Many of the low and middle-income nations located in the tropics are not responsible for climate change. Although they are not major emitters, they are bearing the burden of decisions that have been made by high-income nations,” Conte said.

]]>A goalkeeper from Ghana pursues his ‘right to dream’

As a child in Ghana, Rashid Nuhu attended Right to Dream, a youth development academy that combines soccer training with academic coursework. He earned a scholarship to the Kent School in Connecticut, where he was encouraged to consider Fordham by fellow Right to Dream graduate Nathaniel Bekoe, GABELLI ’14, who played for the Rams from 2010 to 2013.

Nuhu starred at Rose Hill, helping to lead Fordham to the NCAA Tournament quarterfinals in 2018 before earning a degree in economics.

But professional success didn’t come immediately. He was drafted by the New York Red Bulls in 2019 and spent a year in the club’s development system. Without a contract after parting ways with the organization, Nuhu began training at Rose Hill. One day, men’s soccer coach Carlo Acquista told him about an opportunity to try out for Union Omaha in the third-division USL League One, whose coach had inquired about Nuhu.

“I was like, Yeah, why not?” Nuhu says. “I didn’t have a team. If there’s a team that wants me, that’s what I want.”

Nuhu went to the tryout, made the team, and has thrived ever since, winning a championship with the club in 2021 and earning the 2022 Golden Glove award as the league’s Goalkeeper of the Year.

“It was surreal for me, going through hardship,” he says. “I could have given up, I could have quit, but I kept on going and now things are falling into place, and it feels great to see your hard work pay off.”

]]>An investor provides capital for overlooked communities

From the South Side of Chicago to New York City investment banks, Capitol Hill, and Mexico City startups, Israel Muñoz has been all over the map working to change the distribution of capital.

“Even within venture capital, less than two or three percent goes to women, less than two percent goes to people of color,” he says, “and capital is the tool for building the future.”

As a first-generation Mexican American in Chicago, Muñoz became involved in grassroots organizing and activism surrounding public education when he noticed his high school struggling to provide viable resources to students. He earned a scholarship to attend Fordham College at Lincoln Center, where he intended to major in political science but quickly switched to economics—a subject that was “an abstraction” to him until he took an introductory macroeconomics course taught by Michael Buckley, Ph.D.

Attending Fordham at the time of the Occupy Wall Street movement, Muñoz became interested in understanding wealth and income inequality and how economic forces shape the world at large. That curiosity was nourished by his time in the Matteo Ricci seminar, an honors course for students interested in connecting research with community engagement. For Muñoz, the experience deepened his political consciousness and planted the seeds for him to apply for a Fulbright scholarship.

“We spoke about economic inequality and we read Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century. The thoughts about the one percent and power and wealth were really swimming in my head. I think Matteo Ricci just made me a more informed citizen,” says Muñoz, who also earned a Campion fellowship from Fordham’s Office of Prestigious Fellowships that took him to Chile to research education inequality.

Increasingly interested in finance, he interned at UBS, JPMorgan Chase, and in the offices of U.S. Senator Dick Durbin before a Fulbright scholarship took him to Mexico City, where he gained exposure to the Latin American tech ecosystem.

He credits Anna Beskin, Ph.D., then an advisor in Fordham’s Office of Prestigious Fellowships, for her constructive help with his Fulbright essay. “If Anna wasn’t there, I probably wouldn’t have gotten [the opportunity] and become a venture capital investor,” he says.

Since returning from his Fulbright experience Mexico, Muñoz has worked as an investment analyst for the Illinois state treasurer and as an associate at Acrew Capital, a San Francisco-based venture capital fund. He also helped start Angeles Investors, a Hispanic- and Latinx-focused angel investor group.

“I think it’s really important that capital be distributed in a different way,” he says, “so that more of us have a shot at creating the future.”

]]>The 513-page 2023 Economic Report of the President, which was issued on March 23 by the Executive Office of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, cited two papers by Conte and his coauthors in the report’s ninth chapter, “Opportunities for Better Managing Weather Risk in the Changing Climate.”

The papers were An Imperfect Storm: Fat-Tailed Tropical Cyclone Damages, Insurance, and Climate Policy, which was published in the Journal of Environmental Economics and Management in 2018, and Noah’s Ark in a Warming World: Climate Change, Biodiversity Loss, and Public Adaptation Costs in the United States, which was published in the Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists in 2022.

The presidential report, which is transmitted to Congress no later than 10 days after the submission of the budget each year, presents an overview of the nation’s economic progress and outlines plans for the future.

Climate change was first addressed in the report in 2010 and was included intermittently up until 2018 when it was not addressed. It was reintroduced in last year’s report, and this year, it included the weather risk chapter, which addresses the ways that market failures prevent societies from adapting to the increased risk associated with climate change.

Threats No Longer in the Distant Future

The common thread connecting Conte’s two papers is that threats from climate change that were once thought to be distant are in fact present today. The first is cataclysmic “once in a 1,000 years” storms like Hurricane Harvey, he said, that have become stronger in part because of warmer ocean temperatures. The second is the ongoing rapid loss of flora and fauna that the United Nations has estimated will result in the loss of a million species within decades.

“Our research shows that if we want to be able to adapt to these threats from a changing climate, we need to have a better understanding of the full scope of their impacts,” said Conte.

Reluctant Insurers

“The imperfect storm paper shows how challenging it is to adapt to tropical cyclones because they’re infrequent events that can vary dramatically in the magnitude of their impacts. That variability in the impacts of extreme (tail) events makes it difficult for insurers and policy makers to motivate adaptation,” he said.

Recognizing the Value of Biodiversity

“In ‘Noah’s Ark in A Warming World,’ we looked at the impacts of climate change on the species that are listed under the Endangered Species Act in the U.S., and found that there are going to be big increases in expenses that have to be made to try to protect those species.”

Both problems stem from failures of the market, he said, but they manifest themselves very differently. In the first problem, population centers in the United States continue to grow even in areas that are vulnerable to catastrophic storms, as prices in key markets do not reflect the risk of storm damages, meaning that it is still economically advantageous to do so. In the second, there are no markets to provide clear signals of the value of biodiversity, even though diverse flora and fauna are key to supporting human life.

It’s important for the government to address climate change in a report about economic progress, he said, because the market alone is not equipped to solve the problem.

“A well-designed regulatory policy is going to be critical to deal with the challenge of climate change, so the fact that these policymakers are aware of this type of work sends a signal that they are starting to take these risks seriously,” he said.

]]>That’s the question recently addressed by a Fordham student’s faculty-mentored research project. While scholars have long suspected that people with disabilities tend to get left behind in schooling, in employment, and in other sectors of life, the research by Emily Lewis, FCRH ’22, found that there is even more of this inequality in richer countries. And it suggests that policies may be needed to ensure growth and development benefit all people in a society.

Disability “tends to be ignored when we speak about inequalities,” said economics professor Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., co-director of the disability studies minor and founding director of Fordham’s Research Consortium on Disability. “And yet, disability is key when it comes to understanding people’s livelihoods, people’s standard of living.”

Mitra was the mentor for Lewis, an economics and philosophy major who spent last summer analyzing international disability data with support from a summer research grant. Such funding for student-faculty research is a priority of the University’s current fundraising campaign, Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student.

Lewis, Mitra, and economics doctoral candidate Jaclyn Yap are co-authors of the resulting research paper, Do Disability Inequalities Grow with Development? Evidence from 40 Countries, published April 25 in the academic journal Sustainability. The research sprouted from another project led by Mitra that highlights disability inequalities worldwide.

The Disability Data Initiative

Since 2006, more than 180 countries have ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, an agreement to treat them not as objects of charity and medical treatment but rather as contributing members of society.

To support this goal and help policymakers move forward, Mitra spearheaded the Disability Data Initiative, a report on 180 nations’ census and survey findings regarding people with disabilities from 2009 to 2018. She led a team of graduate and undergraduate students, including Lewis.

Presented at a UN conference last June, the report showed that about one-quarter of nations didn’t ask about disability in their national surveys. In those that did, the data showed major gaps in the areas of education, health, employment, and standard of living between people with disabilities and those without them.

The database opened the possibility of doing an extensive study across countries to see if these gaps increased with development—something that had been long hypothesized but not tested on a large scale.

Eager to explore this question, Lewis made it her summer project. Her interest in the disability gap had been sparked during one of Mitra’s classes, at a time when she was looking for a way to get involved in undergraduate research.

“Seeing examples of how different researchers are approaching these questions was really interesting, and got me excited about how I could design this project for myself,” she said.

It was a big project—and a summer research grant gave her the means to spend the required time on it.

Help from a Fordham Benefactor

This and other grants to students were made possible by an alumni benefactor who has long funded undergraduate research—Boniface “Buzz” Zaino, FCRH ’65, whose long career in the investment world exposed him to the joys of researching and learning about new industries. “Once I got into it, it just opened the world, because you do get to explore and focus on areas that become very interesting,” he said.

He has funded students’ research for years, energized by the students’ enthusiasm for their projects, by what their projects have taught him about the world, and by the benefits to the student researchers themselves.

The research process, with its wide reading and focused inquiries, gives students a base for developing their interests and learning about new things over the long term, he said. “The University provides a student with the opportunity to develop a research process, and that’s got to be very helpful for them going forward, no matter what they do in life,” he said.

The Disability and Development Gap

Lewis met weekly with Mitra over the summer to design and carry out the project, examining 40 countries that have comparable data on peoples’ self-reported difficulties with seeing, hearing, walking, cognition, self-care, and communication.

Working on the Disability Data Initiative, they had already gotten glimpses of a wider disability gap in wealthier countries.

For instance, in low-income nation of Cambodia, 75% of adults with any kind of difficulty caused by disability were employed, just shy of the 79% for those without disability. But in economically booming Mauritius, an island nation in the Indian Ocean, the gulf is far wider, with just 15% employment for those with any difficulty, compared to 56% for those without.

To see if such disparities represented a trend, Lewis crunched a big data set including lots of variables—levels of disability, gender, age, and urban versus rural location, as well as a nation’s place on Human Development Index, or HDI, a UN indicator of nations’ wealth and overall development.

She found that for many standard-of-living indicators, like adequate housing and access to electricity, there was little difference in the disability gap between richer and poorer countries.

But the story was different in three areas: education levels, employment rate, and a multidimensional measure of poverty. Gaps in all three increased as countries’ HDI increased. The results held up when Lewis looked at the data a few different ways, such as focusing on different development measures or population subgroups.

The results, the co-authors wrote, “suggest that as a country develops, policies, specifically in relation to education and employment, need to be implemented to narrow and, eventually, close the gaps between persons with and without disabilities.”

The research shows that while disparities may be greater in wealthier nations, disability inequalities aren’t just a problem in rich countries with older populations, Mitra said. Low-income countries have them too, even if they’re less pronounced.

“Even when almost everyone is poor, well, people with disabilities seem to be even poorer,” she said.

Lewis found it exciting to be involved in the research process and see it through from start to finish—figuring out the approach, changing direction as needed, and working independently. “[It’s] something I consider myself really lucky to have been involved in,” said Lewis, who was planning to work as a project assistant at a New York law firm after graduation to explore her interest in law school.

Mitra said that undergraduate research not only teaches students valuable skills but also gives them an inside look at how knowledge is produced, as well as all the caveats and limitations that come with it—an awareness that will serve them well in whatever field they pursue.

The University’s research grant program for undergraduates is “a unique opportunity for students, but also for as faculty,” Mitra said. “So I hope it does continue to attract the generosity of donors.”

To inquire about giving in support of student-faculty research or another area of the University, please contact Michael Boyd, senior associate vice president for development and university relations, at 212-636-6525 or [email protected]. Learn more about Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, our campaign to reinvest in every aspect of the Fordham student experience.

]]>