For years, many have said the blood-sucking critters can jump, but now, thanks to a Fordham researcher, there’s video providing proof—as well as greater insight into the potential skills of leeches, which are seen worldwide but sparingly studied.

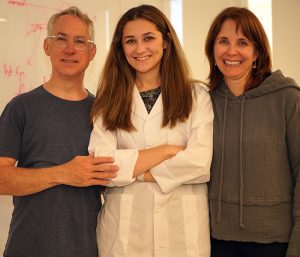

“We know very little about them,” said conservation biologist Mai Fahmy, Ph.D., GSAS ’22, lead author of a June study in the journal Biotropica about a leech of the Chtonobdella genus, found in Madagascar. “We know that they’re found almost everywhere on Earth except Antarctica”—on land and in both saltwater and freshwater, she said, referring to all leech species. “And they’re highlighted in pop culture all the time because of their feeding habits.”

Indeed, those habits might be why scientists have kept their distance, her coauthor said.

“Not a lot of people want to study a worm that sucks blood,” said Michael Tessler, Ph.D., GSAS ’13, a biology professor at Medgar Evers College of the City University of New York.

But the lowly leech is worthy of study, they said. For one thing, the contents of its guts can offer a window into a region’s biodiversity and inform conservation efforts, said Fahmy, a visiting scientist with the American Museum of Natural History and a Fordham postdoctoral researcher working in the lab of biology professor Evon Hekkala, Ph.D.

Captured on Cell Phone

Fahmy was new to the study of leeches when, during a research visit to Madagascar in 2017, she used her cell phone’s video camera to capture one of them leaping from a leaf and landing on the ground. She thought such jumping was documented. But she soon learned otherwise, and during a follow-up trip to Madagascar last year, she got another video of a leaping leech and confirmed the species. The video offers support for prior testimonies of leeches jumping, Fahmy said.

Leeches are already known to latch on when a host animal brushes against them. (Despite their sucking blood, they’re mostly harmless to humans, Tessler said.)

But the leech in question—cylinder-shaped, measuring only a few centimeters, with suckers on its front and back—can do something more. It jumps by rearing back, almost like a cobra, and compressing itself to create tension before releasing it.

These leeches move along surfaces like an inchworm does, but “they’re surprisingly fast,” Tessler said. Still, he said, “they are not something you would necessarily expect to be able to just turn into a little spring and ‘boing’ off of a leaf.”

Measuring Biodiversity

With all the DNA they ingest while feeding on host animals, leeches help scientists get a fuller picture of which animals can be found in a given area, Fahmy said. For instance, leeches might seek out animals that are too small to trigger automated camera sensors or too well camouflaged to be spotted by scientists. Also, she said, they’re “generalist” feeders who aren’t picky when choosing a host.

She’ll be studying leeches for a while yet. Her research focus is on gathering DNA found in nature to study how the diversity of species is affected by deforestation and human conflict, as well as cultural values’ role in conservation efforts. Knowing more about leeches’ ability to jump and reach hosts can help when designing biodiversity surveys, she said.

“Leeches are among the few tools that are able to capture biodiversity across many different taxonomic classes, which makes them really efficient, especially if they’re out there finding you,” she said.

“It’s really gratifying to see how many of the projects lean into our identity as a Jesuit institution,” said Ann Gaylin, dean of GSAS, “and strive to advance knowledge in the service of the greater good.”

Students displayed posters on topics that ranged from biology to theology to economics to psychology.

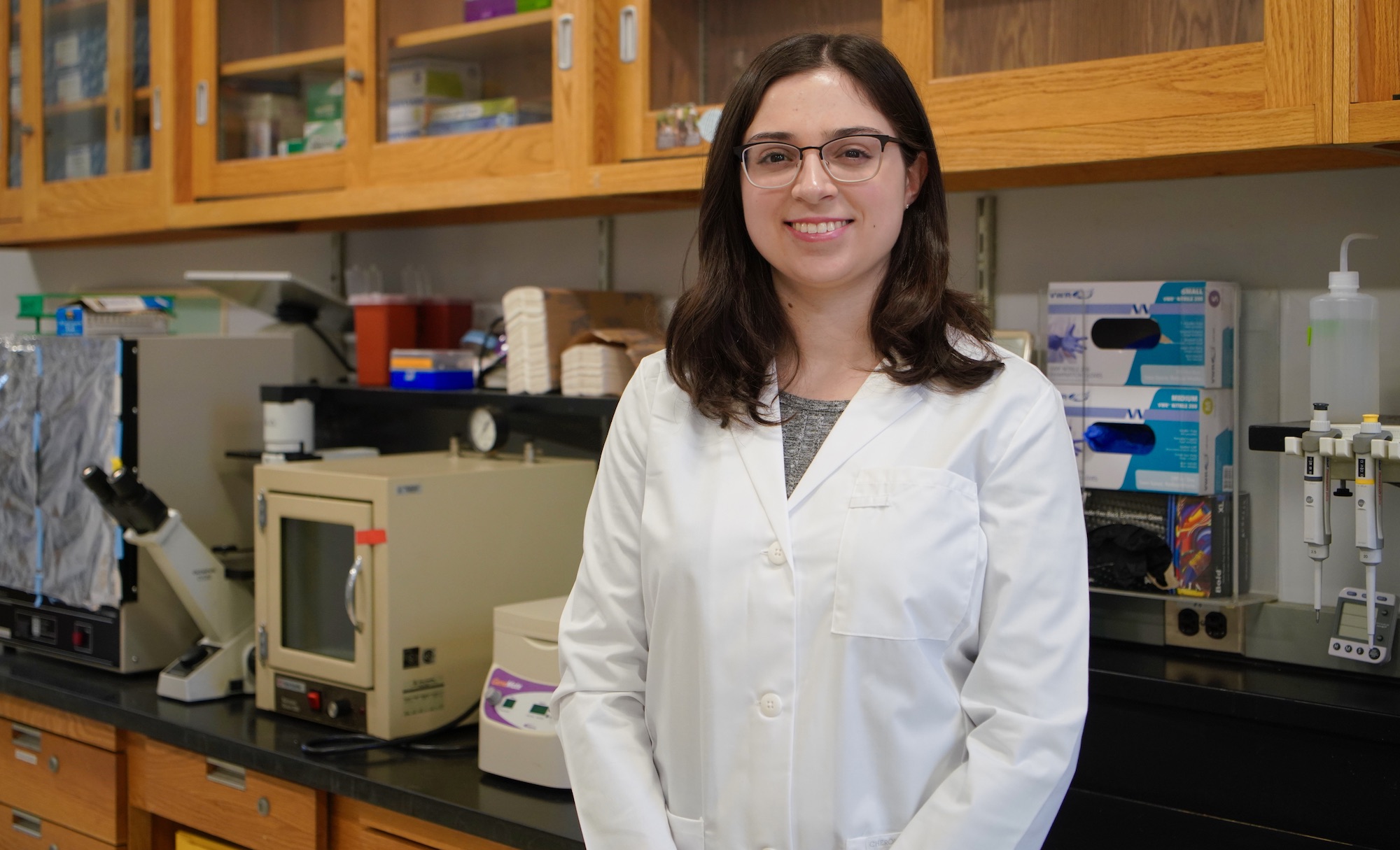

Nina Naghshineh, Ph.D. in Biological Sciences

Topic: The Role of Bacteria in Protecting Salamanders

How would you describe your research?

I study the salamander skin microbiome and how features of bacterial communities provide protection against a fungal pathogen that is decimating amphibian populations globally.

Why does this interest you?

I’m really interested in how microbes interact and function. My study system is this adorable amphibian, but the whole topic is so interesting because microbial communities are so complex and really hard to study. So the field provides many avenues for exploration. These types of associations are present in our guts and on our skin. I’m interested in going into human microbiome work after I graduate, so I have a lot of options available to me because of this research.

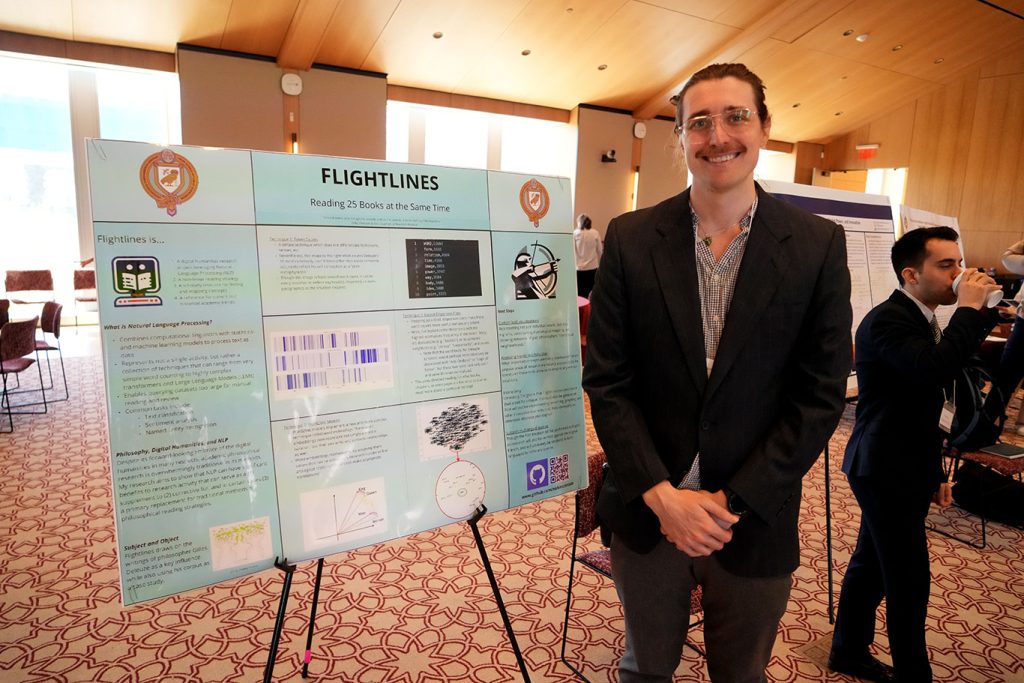

Nicholas McIntosh, Ph.D. in Philosophy

Topic: Using AI to Help Scholars Distill Information from a Vast Body of Texts

How would you describe your project?

It’s a digital humanities project that uses natural language processing to help read and understand many texts at once. There’s this vision we have of a really great humanities scholar who is able to know a text so well that they could almost quote it from memory. That is really difficult for us to do right now in the same way we might have when there were only a couple of touchstone classical texts.

What do you hope this will accomplish?

Scholars are scanning texts either for our classes or for our own research. So this would help us figure out, number one, how can you look at a text and be able to recognize— is this text useful for me? Number two, what are the most important concepts that we should be tracking in a text? And number three, what is the text as data telling us that maybe scholarship is overlooking or overemphasizing given traditional readings?

I would also like to show that those of us who do philosophy don’t have to be afraid of these technologies.

Angel Villamar, Siphesihle Sitole, and Virginia Scherer, M.A. in International Political and Economic Development (IPED)

Project name: Climate Mitigation: The Role of a People’s Organization in the Philippines

What were you investigating with this research?

We looked at the role of the grassroots organization Tulungan sa Kabuhayan ng Calawis in dealing with climate mitigation. It was formed after Typhoon Ketsana hit in 2009. There is an area right outside of Manila that, over the years, has been deforested, so this organization organized to help incentivize reforestation. The farmers in the area, who are mostly women, develop the seedlings, do the land preparation, and plant the trees.

What do you hope people learn from this project?

We want to think about reforestation not as a one-time thing but as a long-term sustainable way. What incentives do you need so that you can keep doing this? We are showing that you can involve ordinary individuals at the grassroots level in something that is much bigger than them.

Answering a call from Pope Francis, Fordham is indeed a place committed to taking “concrete actions in the care of our common home.”

Here are some updates from the first quarter of 2024, from student sustainability interns to “cool” foods to fun community events that make an impact.

Facilities

In January, 11 more undergraduate students joined Fordham’s Office of Facilities Management as sustainability interns to help the University in its efforts to reduce its carbon emissions. They’re working on projects connected to AI-enabled energy systems, non-tree-based substitutes for paper, and composting. The office is still looking for three more students to join; email Vincent Burke at [email protected] for more information.

Dining

Stroll into a dining facility at the Rose Hill or Lincoln Center campus, and you’ll find “Cool Food” dishes such as crispy chicken summer salad, California taco salad, and spicy shrimp and penne.

The dishes, which are marked by a distinctive green icon at the serving station, have a higher percentage of vegetables, legumes, and grains, which generally have a lower carbon footprint than those with beef, lamb, and dairy. According to the World Resources Institute—which Fordham partnered with on the Cool Food project—more than one-quarter of the world’s greenhouse emissions come from food production.

In March, the University went one step further by signing onto the New York City Mayor’s Office Plant-Powered Carbon Challenge. The pledge commits Fordham and Aramark to reduce our food-supply carbon emissions by a minimum of 25% by the year 2030.

Academics

This semester, a new one-credit, university-wide experiential learning seminar titled Common Home: Introduction to Sustainability and Environmental Justice was taught by faculty and staff from the Gabelli School, the Center for Community Engaged Learning, the Department of Facilities, the Department of Biology, and the Department of Theology.

Other sustainability-focused courses this semester include the City and Climate Change, the Physics of Climate Change, and You Are What You Eat: the Anthropology of Food (Arts and Sciences); Sustainable Reporting and Sustainable Fashion (Gabelli School of Business); and Energy Law and Climate Change Law and Policy (Law).

Did You Know?

Like most buildings in New York City, the ones on the Rose Hill campus get almost all of their power from power plants fueled by natural gas (along with some solar power). To power a building like Walsh Library, a natural gas-powered plant normally uses 37 million gallons of water annually. But fuel cells like the ones that were installed at the Walsh Library in 2019 actually make their own water, and as as result, Fordham is saving the community the equivalent of 57 Olympic-sized pools each year.

Students Take the Lead

At Fordham Law School, the student-run Environmental Law Review hosted a March 14 symposium that considered the impact of artificial intelligence on environmental law. Panels focused on how regulators and litigators can use AI and the challenge of addressing AI-generated climate misinformation.

In January, Fordham Law student Rachel Arone wrote The EPA Rejected Stricter Regulations for Factory Farm Water Pollution: What This Means, Where Things Stand, and What You Can Do for the Environmental Law Review. And the Law School’s student-faculty-staff collective Climate Law Equity Sustainability Initiative held a series of lunchtime discussions about climate change, law, and policy.

Student groups LC Environmental Club and Fashion for Philanthropy teamed up on March 8 to create reusable tote bags on International Women’s Day. The bags were donated to Womankind, which works with survivors of domestic/sexual violence and trafficking.

The United Student Government Sustainability Committee continues to run the Fordham Flea, a student-run thrift shop that connects students interested in selling old clothes with those looking to buy sustainably. The next flea will take place on April 26 from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. outside of the McShane Center.

Community Engagement

The Center for Community Engaged Learning (CCEL) held an Urban Agriculture and Food Security Roundtable on Feb. 2. The gathering brought together community organizations and leaders from the Bronx to discuss urban agriculture and food security. Attended by Bronx Congressman Ritchie Torres, the meeting was also an opportunity for groups to learn about resources available from the USDA and the New York City Mayor’s Office on Urban Agriculture.

CCEL Director of Campus and Community Engagement Surey Miranda-Alarcon served as a panelist at a March 9 climate justice workshop at SOMOS 2024 in Albany, along with Mirtha Colon, GSS ’98, and Murad Awawdeh, PCS ’19.

Faculty News

David Gibson, director of the Center on Religion and Culture, and Julie Gafney, Ph.D., director of the Center for Community Engaged Learning, attended “Laudato Si’: Protecting Our Common Home, Building Our Common Church” conference at the University of San Diego on Feb. 22 and 23.

Marc Conte, Ph.D., professor of economics, and Steve Holler, Ph.D., associate professor of physics, presented their research around air quality, STEM education, and education outcomes on March 11 at the first night of Bronx Appreciation Week, which the Fordham Diversity Action Coalition organized.

Alumni

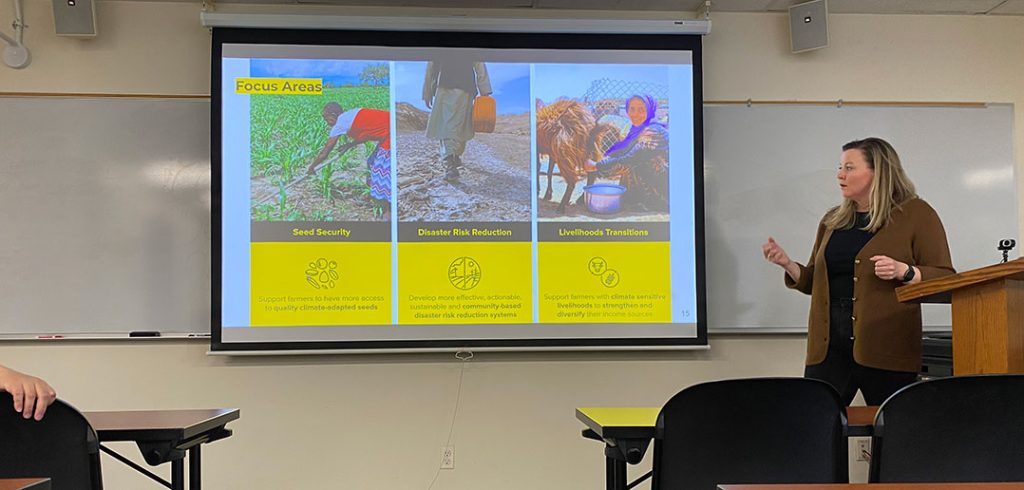

On March 14, Tara Clerkin, GSAS ’13, director of climate research and innovation at the International Rescue Committee, delivered a lecture at the Rose Hill campus titled “The Epicenter of Crisis: Climate and Conflict Driving Humanitarian Need and Displacement.”

In Case You Missed It

Here are some sustainability-related stories that you may have missed: In January, economics professor Marc Conte published the findings of a study that examined whether people living in areas with more air pollution suffer more from the coronavirus. The Gabelli School of Business partnered with Net Impact, a nonprofit organization for students and professionals interested in using business skills in support of social and environmental causes. A group of the Gabelli School Ignite Scholars traveled to the Carolina Textile District in Morgantown, North Carolina, to learn the benefits of sustainable and ethical manufacturing.

Upcoming Events

April 12 and 19

Poe Park Clean-up

In celebration of Earth Day on April 22, the Center for Community Engaged Learning is organizing visits to the park, where volunteers can help pull weeds and spread mulch. 10 a.m. – 2 p.m., 2640 Grand Concourse, the Bronx. Sign up here.

April 13

Bird Watching in Central Park

Law professor Howard Erichson will lead students on a birdwatching tour of Central Park, where they hope to spot and identify a few of the hundreds of species that pass through Fordham’s backyard on their annual migration routes. Meet at the Law School lobby at 9:30 a.m. Contact [email protected] to reserve a spot.

April 13

Ignatian Day of Service

Students and alumni will meet at the Lincoln Center campus and walk over to nearby Harborview Terrace, where they will build a community garden with residents. Lunch and a conversation about Ignatian leadership will follow. 10 a.m. – 2 p.m.

Click here to RSVP.

April 15

ASHRAE NY Climate Crisis Meeting

The theme of this meeting of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers is “Challenge Accepted: Tackling the Climate Crisis.” All are welcome.

7 a.m.- 1 p.m., Lincoln Center Campus. Contact Nelida LaBate at [email protected] for more information or register here using code FordhamStudent2024.

We’d Love to Hear From You!

Do you have a sustainability-related event, development, or news item you’d like to share? Contact Patrick Verel at [email protected].

]]>“I haven’t pinpointed what I specifically want to work on, but I’m eager to do research that has some kind of positive impact on the world, whether that’s helping people or the environment,” Bonanni said. “I want my research to have a bigger purpose.”

Some student researchers focus on a single topic, but Bonanni has dabbled in several—and because of this, she sees the world differently, said a Fordham professor.

“Her experience has given her a good view of different topics. She can ask questions that other people might not be thinking about,” said her academic advisor Patricio Meneses, Ph.D., associate professor of biological sciences. “This will benefit her when it comes to asking the next interesting or necessary question in science.”

‘A Whole New World Opened Up’

Bonanni was born to a family of scientists in Niskayuna, New York. Her father is an electrical engineer at General Electric. Her mother, a longtime optometrist, pursued her career when there were few women in her field. Both inspired their daughter to become a researcher.

Bonanni had always been fascinated by the natural world. In elementary school, she drew three-page pictures of different landscapes and the flora and fauna that lived within them. But in high school, Bonanni realized that science was more than a childhood interest.

“When I took a biology course, it was like a whole new world opened up. I learned how the natural world works, how everything fits together in ecosystems, and how life functions. Once I knew that was a field, I was like, ‘Wow—that’s the one for me,’” she said.

Growing as a Biologist at Fordham

In 2020, she enrolled at Fordham. She wanted to attend school in New York City, and she was drawn to Fordham’s Jesuit ideals.

“I knew that I could find a Catholic community at other colleges, but I liked how Fordham implements the Jesuit values in their course philosophy,” she said.

Bonanni spent her first year on Zoom due to the pandemic. The following summer, she took two tuition-free classes. Among them was a genetics course with biology professor Edward Dubrovsky, Ph.D., whose work she loved so much that she asked if she could work in his lab.

Throughout her sophomore year, they examined the genetic mutations responsible for cardiomyopathy, a disease that thickens heart tissue and can lead to death. Using fruit flies as a model for the human body, they explored a question: Where do the mutated genes that cause cardiomyopathy need to be located in order for symptoms to develop? Any cell in the body or specifically in the heart? (They later learned that the latter was correct.)

Under Dubrovsky, Bonanni learned what it’s like to work in a real lab, versus a classroom.

“When you’re in a research lab, you don’t know what the answer is. Sometimes things don’t go right the first time, but that’s just part of the research process,” Bonanni said. “That uncertainty is where discoveries are made.”

The following summer, she studied in Australia through Fordham’s partnership with the School for Field Studies. For one month, she lived in the rainforest and conducted fieldwork on marsupials.

“It was really cool to learn about how they came to be in Australia and set up field cameras to take pictures of marsupials passing by, like pademelons,” Bonanni said.

Exploring Bronx Plant Life

She loved working with animals, but she also wanted to try working with plants. She had always enjoyed tending to her family’s vegetable garden, where they raised tomatoes, lettuce, squash, and beans.

Last fall, she studied the spread of Japanese knotweed, an invasive species that has spread to the Bronx, in the lab of biology professor Steven J. Franks, Ph.D. She enjoyed the experience, but realized she preferred working with animal cells.

Keeping the Earth Safe for Turtles

This semester, Bonanni started working on a project that combines her interests in cell and molecular biology and ecology.

In the lab of Evon Hekkala, Ph.D., associate professor of biological sciences, Bonanni is studying green sea turtles, the largest hard-shelled sea turtle on Earth. Every year, these turtles return to the same beach to lay their eggs. The problem is only some areas are protected from poaching and other activities that prevent babies from hatching and safely making their way to the ocean.

“If only specific areas are protected, then only specific turtle genes might be protected. That means you’re limiting the genetic diversity of the population,” Bonanni said. “A less genetically diverse population is less likely to survive diseases,” said Bonanni, who is now analyzing DNA from hatched turtle shells to assess their genetic diversity.

The Wonder of the Natural World

Bonanni wants to become a biologist. No matter what she focuses on, she says she wants to hold onto something that we often forget as adults—the wonder of the natural world.

“Growing plants is so exciting when you really think about it,” said Bonanni, who once worked as a summer camp counselor who taught children how to water seeds into sunflowers. “The fact that a beautiful, green, lush thing can come out of a small seed is so cool. As adults, we sometimes lose the wonder associated with that. But when you look at a kid experiencing it for the first time, you remember how exciting it really is.”

]]>Last year, Fordham joined the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s first Inclusive Excellence 3 Learning (IE3) Community. The goal of the initiative is to improve STEM teaching and learning for first-generation college students, transfer students, and students from underrepresented backgrounds.

When it was accepted into the inaugural cohort, the University was assigned to one of seven clusters, each of which is comprised of 15 institutions. The cluster that Fordham joined has been tasked with the narrower goal of making introductory STEM course content more inclusive. This fall, the schools in the cluster were collectively awarded $8.6 million from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and decided as a group to allocate approximately the same amount to each school.

J.D. Lewis, Ph.D., a biological sciences professor, is leading the Fordham team, along with Dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center Laura Auricchio, Dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill Maura Mast, Associate Professor of Chemistry Robert Beer, Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Patricio Meneses, and CSTEP Director Michael Molina.

Lewis said that the collaborative nature of the project is what makes it most exciting.

“So much funding is based on, ‘We’re going to be the first to do something,’” they said.

“But one of the things that’s nice about this is that we are able to move forward faster because we collectively are working together. We’re not saying, ‘Oh my goodness, you made a mistake.’ We’re saying, ‘Oh, that didn’t work, what can we do better this time?’”

At Fordham, the grant funding, which is spread over six years, will be allocated toward faculty development, student engagement, and curricular improvements.

At Fordham, Lewis said, that could take many forms. One idea might be hosting webinars or guest speakers who can talk about some of the issues related to reimagining the introductory STEM experience. Another might be setting up listening sessions between faculty and student-led pre-health profession clubs. The group will also aim to build on previous successes with mentoring and early research experiences, such as Project TRUE, the ASPIRES Scholars program, the Calder Summer Undergraduate Research Program, and Fordham’s Collegiate Science and Technology Entry Program, and share those experiences with colleagues in the cluster.

When it comes to curriculum, Lewis noted that the biology department had already recently reimagined its course sequencing. In the past, Intro to Biology 1 was only offered in the fall semester, and Intro to Biology 2 was only offered in the spring semester of undergraduates’ first year; both are required courses for STEM majors and are notoriously tough courses that “weed out” those who can’t complete the course load. But that meant new students had to take Intro to Bio 1 their very first semester of college, which was problematic for students who might not have had a rigorous science background in high school. So last year, the department began offering both courses in the fall and the spring. The new schedule provided flexibility without compromising the rigor of the courses.

That’s the kind of success the department wants to build on with the help of other experts.

“It’s talking with a sociologist or a psychologist and bringing in folks who have had experience in how to ease students’ stress and anxiety around the introductory STEM sequence simply by changing how the material is presented, even if it’s the same material,” Lewis said.

Molina agreed that small changes like that can have a big effect on a student who has shown great promise academically, but who is entering college after attending a high school that did not have a full-time, fully licensed biology teacher. Through no fault of their own, that student will have a steeper learning curve when they begin college-level studies.

“Part of the challenge of keeping all students, but particularly under-represented students, engaged in STEM course work is to make sure every student is able to meet the challenge of “gateway” courses in the physical and natural sciences on their terms,” he said, adding that the flexibility also gives them the chance to learn new study habits.

“If you’re able to bridge that gap of how you study from high school to how you study in college, it makes all the difference in how successful you’ll be, and how confident you’ll be going forward.”

When it comes to the future, Molina said he’s excited to be a part of efforts to bring incoming students onto campus and into science labs as soon as possible and to make the student-professor relationship less hierarchical and more collegial. The grant will make it possible to undertake these sorts of initiatives.

“We want to create a more collegiate relationship between faculty and students, where students feel comfortable coming to faculty, and talking with them inside the classroom and outside the classroom. It’s that kind of culture that breeds success,” he said.

]]>Robin Happel describes global climate change in terms both vivid and personal: the wildfire smoke that was so thick she “could barely see the road” while going home to Tennessee in 2016. The California friends encircled by wildfire who had to drive through flames that melted their tires. The Fordham roommate whose home city was flooded during Hurricane Harvey in 2017. And Hurricane Florence, which flooded her own family’s house the year after.

She related all this not at a policy forum or in front of a class, but during her valedictory address at Encaenia in May 2019, taking advantage of the large, attentive audience at the traditional pre-commencement event for Fordham College at Rose Hill graduates and their families.

“This isn’t a story about what I overcame, or what so many of us have overcome. This is a story about how no one should have to,” said Happel, who majored in environmental studies. “There’s still time to fix this, but only if we start right now. Together, we have the power to solve the climate crisis.”

That crisis is getting more public attention because of nature itself, as wildfires have ravaged the West Coast this year and stoked public concern about extreme weather in a warming world. At Fordham, professors who have spent decades observing the effects of climate change offered insight into how science can help frame the need to take action.

Preserving Ecosystems

To build support for climate action, “you have to explain to people that their own survival depends on it, using economic terms and then health terms,” said Craig Frank, Ph.D., associate professor of biological sciences.

With species struggling—and possibly failing—to adapt quickly enough to rapid warming, natural processes that sustain humanity could be disrupted in ways we can’t anticipate, he said. In his own research at the Louis Calder Center, Fordham’s biological field station in Armonk, New York, he has seen eastern chipmunk populations drop by about two-thirds over the past two decades.

Warmer temperatures have changed the chemistry of seeds they feed on, preventing the chipmunks from lapsing into an energy-saving state of torpor while hibernating underground. To make it through a wakeful winter, they often need to gather more food than can be found in the forest, where trees are producing fewer seeds because of hotter and drier summers, Frank said. He estimated that nearly 1,000 mammal species use torpor in one way or another. It’s not clear, he said, how many hibernating species could adapt to environments that are changing at “an artificially rapid rate” due to growing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

“We’re already in a situation where between 20% and 30% of the mammals in the world are threatened with extinction,” a figure that would grow substantially if warming temperatures keep disrupting hibernation, Frank said.

The highest rate of extinction is among plants, said Steven Franks, Ph.D., professor of biological sciences.

He has led or contributed to studies showing how field mustard plants are affected by extreme weather shifts. While they adapt to flower earlier in response to droughts, their seed production suffers, and earlier flowering can leave them more vulnerable to disease, he said. And when the plants respond to wetter periods by evolving to flower later, it’s that much harder for them to readapt when drought returns. The plants used in the studies were harvested in a part of California that, since 2004, has seen several droughts as severe as any in the prior 100 years after seeing only one such drought since 1977.

Drought is having “an enormous effect on many plants, and water scarcity is a really pressing environmental issue,” he said. “The population can be evolving and can even be evolving rapidly, but still not adapting fast enough to keep up with the rate of climate change, and the population still goes extinct.”

The rate of extinctions is accelerating, with about 1 million species—both plants and animals—at risk of dying out, “more than ever before in human history,” according to a 2019 statement by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Many of them could go extinct within decades, the organization said.

Frank highlighted what else could be lost or affected when species die out. “The air that you breathe is a result of natural processes,” he said. “The food that you eat is a result of natural processes. The soil that grows the food is produced by natural process. The water that you drink, that’s a natural process, too. All these are what we call ecosystem services provided to [us].” And yet, “we don’t fully understand how the ecosystems work or how they’re interrelated,” he said.

Using an analogy from the naturalist Aldo Leopold, he likened degraded ecosystems to an airplane losing rivets from one of its wings in midflight. “Each one of these rivets is a species, and we don’t know when the wing is going to fall off,” he said.

Consequences Big and Small

Thomas Daniels, Ph.D., associate research scientist and director of the Calder Center, noted the importance of getting people to care about nature and about future generations—not “by yelling at them,” but by setting an example. National leadership and political will are critical, along with cultivating an appreciation of nature among the young, he said.

Occupying 113 acres, the Calder Center serves as a laboratory where many subtle, still-unfolding impacts of climate change can be seen. Daniels’ own research specialty is ticks, the tiny arachnids that can transmit Lyme disease. Studying their population at the center over the years, he has seen them becoming active earlier in the spring and later into the winter because of rising temperatures. The warming climate has also allowed the Asian tiger mosquito, a possible vector for yellow fever and dengue viruses, to show up in Orange County, New York—“farther north than we expected,” he said.

While this is worrisome, “the larger picture is so much more devastating than vector-borne diseases being an issue,” he said. “The consequences [of climate change] go so far beyond us, and our particular risk in a particular location on a particular day, or in a particular year.”

Those consequences can range widely, from rising seas to food shortages to ocean acidification to an increase in climate refugees who are driven north by rising equatorial temperatures, said physics professor Stephen Holler, Ph.D., who will teach a new honors course on climate change in the spring 2021 semester. Emissions of carbon dioxide from human activity are contributing to the planet’s sixth major extinction event, which follows five others that also correlated with heightened amounts of this greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, he said. The most recent major extinction was the one that wiped out the nonavian dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

He noted the value of showing how people can immediately benefit from actions to curb climate change. As part of the University’s Reimagining Higher Education initiative, launched in spring 2020, his team of faculty and staff members devised a project for communicating climate science through the lens of air pollution and how it affects people who live in the Bronx. It will bring together students from Fordham and from Bronx elementary and high schools to educate the community about air quality, using data from particulate sensors to be placed at the Rose Hill campus and throughout the Bronx.

Their goal is to empower residents to take social or political action about air quality in the borough. The Bronx has some of the country’s highest rates of asthma, which is exacerbated by particulates in the air, Holler said.

“These are everyday issues that have significant emotional and financial impacts and illustrate the adverse effects of climate change on the local level,” he said.

Holler’s course will cover social justice aspects of climate change, such as populations displaced from Pacific islands—as well as parts of the U.S.—because of rising seas, in addition to droughts and other environmental impacts.

Taking Action

In her speech at Encaenia, Happel called on her audience to work on climate issues with other members of “Fordham’s amazing global network, [f]rom bankers to biologists, diplomats to dancers.” And she called out one particularly inspiring Fordham graduate, a head of state who is “a powerful voice on the world stage for the rights of island nations.”

That alumna is Queen Quet Marquetta L. Goodwine, chieftess of the Gullah/Geechee Nation. A graduate of Fordham College at Lincoln Center, for the past 20 years she has been the elected leader of this internationally recognized nation populating low-lying coastal areas and islands stretching from North Carolina to Florida. “It’s no stretch of the imagination to say that, someday, her country may simply cease to exist,” Happel said.

To avoid that outcome, Queen Quet has become a high-profile voice on climate issues, speaking at the United Nations and testifying before Congress while also working on smaller, more local efforts. (See related story.) In an interview, she touched on the importance of plain language in describing climate change and getting people to care. One of her projects is devising educational materials to explain the concepts of heat islands and ocean acidification. “Just because we throw around these terms in the environmental world, doesn’t mean the average person knows what we’re talking about,” she said.

Immediate actions can counter the feeling that the issue is too complicated and beyond one’s control, Franks said. It’s important to “promote the positive ways … we can change our major patterns of consumption … in a way that’s really going to be sustainable and beneficial for us as well as natural populations,” he said.

One example is choosing energy sources other than fossil fuels, he said. In her current studies toward becoming an environmental lawyer, Happel is learning about the importance of getting involved in local government to ensure clean energy is an option.

“So much of our energy grid is regulated through state public service commissions,” she said. “Even though I think a lot of us focus on national policy, state and local policy have a huge impact on whether you’re able to have clean energy in your neighborhood.”

Happel’s remarks at Encaenia in 2019 were part of the youth-led “Class of 0000” campaign to focus graduation speeches nationwide on the issue of climate action and convey its urgency.

“So many students and parents came up to me after that and thanked me for it, and said they thought it was really important,” Happel said. “So many people are impacted now. I think the landscape has changed so much, just in the past few years.”

See our related story, “Alan Alda on Creating a Good Communications Climate.”

]]>Au-Yeung’s research focus is multiple sclerosis, one of many conditions for which the company is developing therapies. At Fordham, majoring in biological sciences, she discovered not only the joys of research but also many other sources of inspiration.

What are some of the reasons why you decided to attend Fordham?

Having been raised in small-town Wilton, Connecticut, I knew I wanted to experience college in the city. Fordham was perfect because it also had such a classic campus atmosphere. And I have always valued small classes because I learn best not only by being challenged but also through actively engaging in discussions and debates. So Fordham was the right choice for me because of the smaller classes with passionate professors teaching them.

What do you think you got at Fordham that you couldn’t have gotten elsewhere?

Prior to coming to Fordham, I was only excited to learn about things pertaining to my major, biological sciences, but through the University’s core curriculum, I was exposed to so many different classes I never would have taken otherwise. I’m thankful that I took these courses because they refined the way I question and think about virtually everything: religion, ethics, myself, the health care industry, et cetera. I gained new interests through many of my core courses, such as Buddhism in America, and Intro to Bioethics challenged many preconceived beliefs I had about the healthcare industry and controversial ethicists.

Did you take courses or have experiences at Fordham that helped you discern your talents and interests and put you on your current path?

Originally I was set on going to medical school after graduating and did not consider anything else. To build my resume and earn money, I applied for an undergraduate research grant for the summer of 2017. Working at the Calder Center, I studied the use of eDNA—or DNA that animals leave behind in their environment—as part of biodiversity and conservation studies at the center.

This experience changed everything for me. I enjoyed it so much that I applied for another grant and worked on cell/molecular research in Associate Professor Patricio Meneses’ lab. These academic experiences motivated me to try out industry research, so I applied for an internship with Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, where I work now. This internship affirmed for me that I wanted to change my medical school plans and pursue research instead. In the spring before graduating, I worked part time at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, contributing to global HPV and HIV studies, after finding this position through Fordham.

Who is the Fordham professor or person you admire the most, and why?

Patricio Meneses—I took his cancer biology and introductory virology classes, and he was my lab mentor. He helped give me the confidence to pursue the life I wanted after I graduated. His intelligence is admirable and his life story of getting where he is today is inspiring. He didn’t discover his passion or “dream job” by following one path; he went through different career paths, all of which led him to where he is today. It’s admirable because I am a planner, and his story and advice remind me that you don’t necessarily have to know where you want to be a year from now.

Can you describe your current responsibilities? What do you hope to accomplish, personally or professionally?

I’m a research associate working in Regeneron’s Immune and Inflammation Group. My group focuses on autoimmune diseases, but I specifically work on multiple sclerosis. My responsibilities include developing, optimizing, and testing candidate therapeutics for MS in mouse models and downstream analysis of associated disease-related pathologies. My professional goals are to continue learning (since the learning curve is steep), and my long-term goal is to become a scientist.

Is there anything else we should know about you, your plans, or your Fordham connection?

While I love science, I also love to travel, paint, cook/bake, and run long distance. I also would love to be a resource for current pre-med students or help out in any way I can as a proud Fordham alumna.

“Dan Sullivan was a man of great faith and great intellect,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham.

“He was the embodiment of the Jesuit ideal, expressing his faith through scientific research and teaching. He was also a man of great practical wisdom and a warm and thoughtful colleague. Today the Fordham family mourns with Dan’s friends and loved ones. He will be sorely missed.”

A native of Rosedale, Queens, Father Sullivan joined the ROTC as an undergraduate, and was one of the founders of the Fordham company of the Pershing Rifles Military Society. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the United States Air Force Reserves in 1950. He entered into the Society of Jesus three months after his graduation in 1950; he was ordained in Innsbruck, Austria, in 1961 and pronounced his final vows in 1979 at Rose Hill.

Pairing Faith and Science

From the very beginning, Father Sullivan seamlessly paired a love of science with his religious calling. As a seminarian, he earned a master’s degree in biology at Fordham in 1958 before heading to the State University of Innsbruck in Austria for five years of studies under the tutelage of esteemed theologians Karl Rahner, S.J., and Josef Jungmann, S.J.

Before he returned to New York, Father Sullivan earned a doctorate of philosophy in entomology from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1969. There, he trained in the science of biological control, in which beneficial insects are enlisted to attack and control insect pests that destroy agricultural crops. He joined the Fordham faculty that year as an assistant professor, then went on to become a full professor in 1984.

Among the major works he published were “Aphids” in Encyclopedia of Entomology (Kluwer Academic Publishing, 2004), “Influence of Host Plant Resistance on Activity and Abundance of Natural Enemies” in Biological Control of Insects (Phoenix Publishing, 2003), and “Hyperparasitism” in Encyclopedia of Insects (Academic Press/Elsevier Science, 2003).

Father Sullivan lent a great deal of his talents to helping the international scientific community. In 1984, he traveled to Nigeria on a Fulbright fellowship to join a team doing research on the cassava mealybug; in 1988, he was a visiting scientist in at the Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT) in Cali, Colombia. He was also the visiting scientist at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in Andhra Pradesh, India, in 1999 and again in 2004. He also had the honor of serving as President of the New York Entomological Society and President of the Fordham Chapter of Sigma Xi -the Scientific Research Honor Society.

In a Fordham News podcast last year, Father Sullivan said his Jesuit superiors actively encouraged him to travel and conduct research.

“Non-Catholics sometimes think there’s a contradiction between belief in God and science. It’s not that way at all. It complements it, in fact. I look back on some of the great scientists. Galileo was a Catholic. And Darwin, although not a Catholic, was a religious man,” he said. “And then of course one of the great geneticists, who started genetics, was Gregor Mendel, who was an Augustinian priest.”

An Invaluable Source of Knowledge

After retiring in 2006, Father Sullivan stayed on the faculty, living at Kohlmann Hall, and advising junior and senior biology students. At that time, he began sharing office space on the fourth floor of Larkin Hall with Craig Frank, Ph.D., a professor of mammalian ecological physiology and biochemistry, who’d joined the faculty in 1994.

Frank said that the letters of recommendation that Father Sullivan wrote enabled countless students to advance to medical school and graduate programs, and noted that many remained in contact with him after graduation.

In the Fordham News podcast, Father Sullivan shared some of the advice he’d dispensed to students over the years.

“I tell my students that the really great scholars in this world are not gonna give you a hard time. It’s the second-raters that do that,” he said.

Frank said that their office hours only overlapped once a week, but they developed a rapport over the years such that, several years ago, someone taped a picture of The Muppets characters Waldorf and Statler on their door. It was a testament to Father Sullivan’s good humor that he let it stay up, Frank said.

Though the biology department existed before Father Sullivan taught there, Frank said his contributions were numerous and influential.

“He was one of the founding fathers of the biology department. He was a very good friend, very pleasant to talk to, and his wit never diminished with age,” he said.

“He was an invaluable source of knowledge, and I viewed him very much as a mentor, even as recently as last week. I would just love sitting in our office during our office hours together, and just talking with him about university life. We didn’t always agree on everything, but it was always a joy talking to him.”

An Unmistakable Fidelity to Fordham

Father Sullivan’s fidelity to the biology department and the University was unmistakable. Every year, the annual newsletter detailing recent events of the department had his byline on it. This year, he penned the paper Historical Profile of the Biology Faculty: Past and Present. He also delivered the invocation and benediction at Fordham’s ROTC’s commissioning ceremony each May. Captain Dan Millican, executive officer and assistant professor of military science in the ROTC program, noted that Father Sullivan attended a 70th anniversary celebration of the Pershing Rifles just two weeks ago at West Point.

“He was a great supporter, and a great influence among the cadets,” he said.

“He could always drive the tone of the room to be more productive, and drive cadets toward service.”

In 2009, Fordham honored Father Sullivan with a Bene Merenti Medal for 40 years of service, citing his career as one that “reflects Ignatius Loyola’s international vision for Jesuits.” Jason Munshi-South, Ph.D., an associate professor of biological sciences, said he was the most dedicated attendee at the department’s annual colloquium.

“I can’t imagine these seminars without his presence near the front every week. He was always able to make a personal connection with the seminar speaker given his varied travels around the world as a Jesuit and biologist,” he said.

Patricio Meneses, Ph.D., the chair of the biology department, echoed the sentiment.

“Father Sullivan made me and every new faculty member feel at home from the first day,” he said.

“He was a true scholar, a great colleague, and a great friend.”

A wake for Father Sullivan will be held Monday, Nov. 25, from 3 to 5 p.m. and 7 to 8:30 p.m. at the Murray-Weigel Hall Chapel, Rose Hill Campus.

A Mass of Christian Burial will take place Tuesday, Nov. 26, at 11:30 a.m. at the Murray-Weigel Hall Chapel, Rose Hill Campus.

Notes of condolence may be sent to a cousin, Kevin Giuliano, 67 Sandburg Place, Pine Bush, NY 12566.

]]>“Depression is very misunderstood,” she said. “If we can figure out an exact chemical path to understand why this happens in the brain, then we can come up with better treatment plans and better medications.”

This past summer Reisner, a sophomore biology major in the Department of Natural Sciences at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, mapped neurons in the brain associated with motivated behavior. The research was conducted at Columbia University as part of a program sponsored by Fordham’s Office of Research that matches students with other New York-based institutions. Officially known as the Fordham-Columbia, Fordham-NYU and Fordham-IBM Research Fellow and Research Intern Program, the effort promotes research collaborations between the four institutions.

“We are using this kind of program to find connections between students and outside research opportunities to make sure we retain best and the brightest,” said George Hong, Ph.D., chief research officer for the University.

This year, the collaborative research program focuses on five specific areas of study: neuroscience, cybersecurity, social innovation, global studies, and urban studies. Hong said he met Reisner at an award ceremony and was very impressed with her enthusiasm for research.

“The students in the program are very enterprising and sometimes we need to find innovative ways to expand our resources to support them,” said Hong.

Reisner’s research was supervised by Eduardo Gallo, Ph.D., assistant professor of biological sciences at Rose Hill, and Christoph Kellendonk, Ph.D., an independent investigator in the Departments of Pharmacology and Psychiatry at Columbia. The project is in its intermediate stages and the scientists hope to have preliminary results this fall.

“A lot of times students are looking to do research and while we cover many different scientific disciplines at Fordham, they may not find a lab that matches their interest,” said Gallo. “They want to get their hands on their topics of interest. I’ve seen it. It reenergizes their passion for science when they do.”

Gallo said the program’s benefits have been two-fold: it provides support for the lab to undertake new research topics and it provides students with a funding opportunity to do research over the summer.

“This has allowed us to work with a lab where they do these types of projects routinely, students learn those techniques and bring them back to Fordham,” said Gallo. “This helps foster collaboration, and the scientists there see we have strong labs and talented students.”

Gallo, whose lab is at Rose Hill, said the program also helps foster collaboration across the University, providing the means for Reisner to work in labs on both campuses in addition to Columbia.

“She’s a Lincoln Center student so this mechanism also provides the opportunity for her to travel up here to Rose Hill and be a part of my lab, where she also does her work and interacts with Rose Hill students,” said Gallo.

Jason Morris, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Natural Sciences at Lincoln Center, agreed that both campuses are benefiting from the program.

“In addition to all the student research we mentor here at Lincoln Center, we’ve had several of our students in this program this year. In years past we’ve had informal arrangements with major research institutions around New York, so we are very pleased that the Research Office is formalizing some of those relationships,” said Morris.

Mapping it Out

Reisner’s specific area of interest deals with mapping physical connections in the brain.

“By mapping the connections, I hope to understand the energizing of behavior in pursuit of a goal,” she said. “For example, overcoming obstacles to obtain food and water, or working hard all semester long to get A’s.”

In the brain, the ventral pallidum and nucleus accumbens are regions critical for many types of motivated behavior. While there is evidence linking them to motivation, little is known about the function of the different neurons within them and how they connect to the rest of the brain, she said. Specifically, she’s focused on cholinergic projection neurons of the ventral pallidum in an attempt to figure out which neurons throughout the brain connect to them specifically.

“If we know who sends information to them, we can then study what the function of that connection is,” she said.

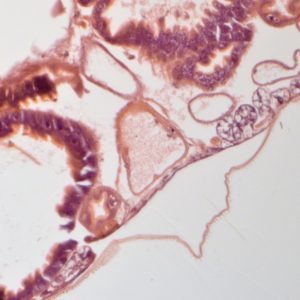

To create a visualization of the map, the general practice is to inject a genetically engineered virus that infects the cholinergic neurons to make them glow with a fluorescent protein that helps in the visualization. The virus then jumps only to cells directly contacting them and those cells, in turn, express the fluorescent protein.

“We can then look for fluorescent neurons all over the brain and establish where they are located and what kind of information they may be passing along to the cholinergic cells,” she said. “Piecing this together may help us understand not only how motivated behavior works, but also may provide clues on how to alter it in cases where it is maladaptive, as in drug abuse, depression, ADHD, schizophrenia, and other disorders.”

Gallo concurred.

“In the field, we have a saying, ‘Neurons that fire together wire together.’ In the future this study may provide a map on where we need to focus, where we see robust connections of the neurons of interest,” said Gallo. This may open many new research avenues for our students.”

Researching from Experience

Reisner knows from personal experience that science and research can make a difference in the lives of people suffering from a variety of motivational disorders.

“I have really bad anxiety and I’ve struggled with it since I was a kid,” she said. “It’s a panic disorder and I’m very open about it.”

Her grandfather wasn’t as fortunate. She said that growing up in Alabama she witnessed how hard it was for him get the correct medications. She also noted how social stigma exacerbated an already difficult situation.

“I’m thankful that I’m not growing up in the ’70s and ’80s when we didn’t understand mental health as well as we do now,” she said.

Today, she said she and her family understand that mental illness is by and large genetic. She said her grandfather has good days, bad days, and some days where he doesn’t want to leave the bed.

“People thought, especially being the man of the household in Alabama—people think that you’re crazy and people think that you are incompetent,” she said. “And just the way he’s kind of overcome this and now he’s so much better is inspiring to me.”

She said that finding the right medication is key, and a key part of why she does her research. She said he went through “a million different medications and treatment plans.”

“I just wish he didn’t have to go through all of that to find what’s actually wrong,” she said. “And then for me, I relate to a lot of it with him because we struggle with a similar issue.”

Back to Work

Returning to campus just before the semester started, Reisner swung by Lincoln Center’s newly renovated lab with her parents and talked about her experience.

“At Lincoln Center, all of my science professors know my name and they know what I’m interested in,” she said. “And then at Rose Hill, I had this opportunity where I can go into a lab and they know exactly what I’m interested in studying. And then they can kind of work with me and say, ‘Okay, you’re very unique because you like this. So, how about we put you in contact with this professor,’” she said, adding that they also connected her with a professor that got her into the Fordham-Columbia program.

She said that she’s happy to be back at Fordham and appreciates the opportunity that the collaboration has afforded her.

“It’s amazing how we can be in collaboration with Columbia and I can still be in a specialized school like Fordham where everybody knows my name, everybody knows what I like to do, everybody knows my interests.”

Gallo said that being a part of a collaborative effort is an important aspect of research that must be taught alongside the science.

“The collaboration provides outcomes for our lab, but it also helps expose students to other scientists,” he said. “It’s also about talking to people and being in the mix, being a part of New York’s neuroscience community. It gives students an idea of where they want to go in the future and career possibilities they may want to explore.”

]]>

Some of Fordham University’s brightest master’s and doctoral students showed that the possibilities are boundless at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences’ second annual Three Minute Thesis competition March 13 at the McNally Amphitheatre on the Lincoln Center Campus.

The Three Minute Thesis competition, founded at the University of Queensland in Australia in 2008 and now held at over 600 universities across more than 65 countries, gives participants just three minutes to explain their research to a non-specialist audience—and tell them why it matters.

Seventeen GSAS students gave engaging and informative talks explaining their thesis or dissertation research, covering a diverse array of topics ranging from Latin American monetary policy to anxiety disorders in HIV-positive youth.

The challenging exercise places students outside of their academic comfort zones, but the skills required to relate complex topics to a generalist audience are extremely useful, said Melissa Labonte, Ph.D., GSAS interim dean.

“It’s not just about presenting for this competition; it’s about using the skills of good communication to be able to clearly explain the value of your work,” Labonte said. “That’s a self-advocacy tool that doesn’t diminish the value of your work—in fact, it amplifies it.”

Far from “watering down” their subject matter, several presenters said they found great value in the process of distilling their work to its essential elements.

“History is all about building up context,” said Louisa Foroughi, a Ph.D. student in the Department of History who won third place for her lecture on the status and identity of yeomen in medieval England. “But this kind of work is about stripping away and thinking about what are the really key moments and events and themes that have to come through in order for my topic to make sense.”

Ana Rabasco, a psychology doctoral student, won first place for her presentation “Risk Factors for Suicidal Behaviors Among Transgender and Gender Non-Binary Individuals.”

Rabasco’s research explores the underlying dynamics behind high suicide rates among transgender and gender non-binary, or TGNB, individuals—40 percent of whom attempt suicide at some point during their lifetime, as compared with roughly 4 percent of the general population. Her survey of TGNB individuals found that current victimization is the most salient risk factor for future suicide attempts, ranking higher than past victimization, body satisfaction, and even depression.

“What this tells us is that TGNB individuals attempt suicide in large part because of dangerous, toxic, and harmful environments that they’re living in,” Rabasco said. “And therefore, if we can improve those environments, we can help to reduce that high rate of suicide among TGNB people. We have to do more than just bring suicide out of the margins, although that’s really important too. We also, as a collective community, have to come together to create an environment that’s accepting, respectful, and kind to all people, regardless of gender identity.”

Alexander Elnabli, a philosophy doctoral student, won second place for his presentation on teaching students to thoughtfully explore the

tensions between secular education and traditional religious values, which drew on his experience as a sixth-grade English teacher in Cairo during the Egyptian Revolution.

At the conclusion of the program, audience members voted for their favorite presentations. The “People’s Choice” prize went to Elle Barnes, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biological Sciences, who explained her research on how urbanization is leading to changes in the bacteria present on the skin of New York City salamanders, impacting their vulnerability to disease. She hopes her work will also expand knowledge about how microbes in humans impact our own susceptibility to disease.

“What can we learn from these tiny worlds? And can we use them to our advantage? These are the types of questions I’m answering with my dissertation,” she said.

– Michael Garofalo

]]>But a recent study by Fordham scientists has found that plants that adapt to wild swings in precipitation still suffer adverse effects, including a reduction of seed production.

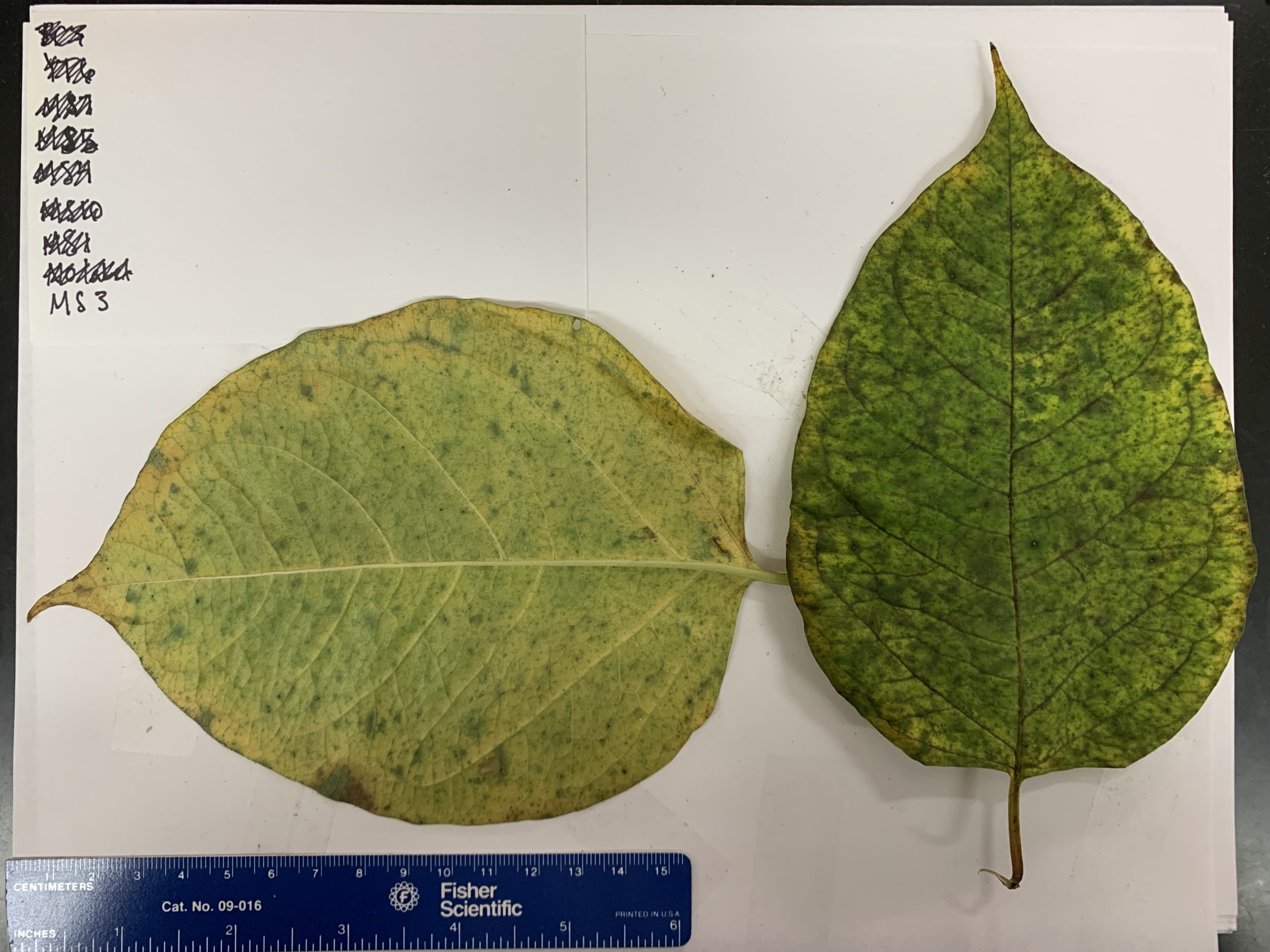

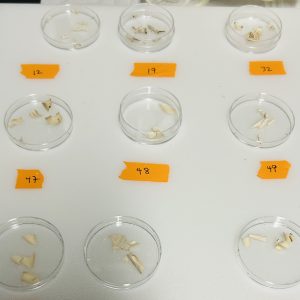

For the study, Elena Hamann, Ph.D., a biological sciences post-doctoral researcher, and Steven Franks, Ph.D., professor of biological sciences, harvested seeds from two collections of Brassica rapa plants in Orange County, California, that had experienced two decades of dramatic precipitation fluctuations, including increasingly severe droughts.

Hamann then grew four generations of plants in September 2016 under both drought and normal conditions in a greenhouse at the Calder Biological Field Station in Armonk, New York, and compared how the two different sets fared.

Franks had confirmed the ability of Brassica rapa to evolve rapidly in earlier studies, but this study took it one step further: The plants that had evolved to cope with drought by doing things like flowering earlier in the growing season, then had evolved to cope with heavy rainfall, then had evolved again to cope with more drought, showed signs that the constant changes were taking a toll.

“In the long term, the droughts are becoming more and more severe, and we’ve also seen that in more recent generations, the plants are not able to maintain fitness as well, so they produce less seeds,” said Hamann, who was the study’s principal investigator.

Photo by Chris Taggart

“So, we think that even though they adapt to drought by advancing flowering time and changing other specific traits, they are starting to suffer from the severity of drought. What they’re doing is basically not enough anymore.”

One of the most significant findings of the study is that paradoxically, rainy seasons actually hurt the plants’ ability to evolve in ways to cope with drought.

“After just two wet years, they flowered much later, but then there was another severe drought, so they then had to sort of evolve into earlier flowering again,” said Franks.

“But there’s a delay and they have less fitness, and produce fewer seeds. So they get fewer seeds into the seed bank for the next generation.”

The ability of a plant like Brassica rapa, which is closely related to turnips and bok choy, to weather droughts and rainy spells is important because wild swings in precipitation are the result of climate change that is likely to continue. In the area of California where Hamann and Franks harvested the plants, for instance, the most severe level of drought in 100 years happened only once between 1977 and 2004. But since then, the area has experienced several droughts that are equally severe or worse.

“The most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change suggests that climate is changing even more than we thought,” said Franks.

“We’re seeing all these really substantial changes in this California system. Plant populations are responding, but there’s good evidence from this study that they may not be able to keep up with the severity of these changes.”

The results of the study, Two decades of evolutionary changes in Brassica rapa in response to fluctuations in precipitation and severe drought, was published this month in the journal Evolution.

]]>