Full transcript below

J.D. Lewis: The eureka moment was in an English class. We were talking about The Merchant of Venice and we were talking about Portia, and the teacher said, “So you have to consider Portia as being a girl in a boy’s body, acting like a boy.” I was like, oh, that’s me. And so that was essentially the point at which I realized this is what my gender is.

Patrick Verel: When President Obama’s Department of Education issued guidance in 2016, that schools should allow students to use the bathroom that matches their gender identity, it was hailed as groundbreaking by supporters of transgender rights. But when Donald Trump took office in 2017, it only took a month for his administration to reverse course. Fast forward to 2021. Joe Biden reinstituted the guidance, and efforts to lift up and support people who identify as non-binary continue. In June of that year, for instance, the state of New York began offering the option of an X gender to anyone who did not identify as male or female. The federal government followed suit in September, allowing people to choose it on their passports. For those of us who are old enough to remember when President Bill Clinton signed the anti-gay Defense of Marriage Act in 1996, it’s fascinating how much things have changed. Over the last few months, I’ve talked to Fordham folks who have had insights to share in the topic of gender, either because of their work, their personal experience, or both. I’m Patrick Verel, and this is Fordham News.

When I first met J.D. Lewis, a professor of biology at the Calder Center in 2011, they had presented as male. At an event in 2019, Lewis presented as female. We recently sat down to talk about that journey.

Now, you told me that you realized something was different about you when you were four years old, right?

JL: Yes, that’s correct. And so two big events both occurred at the same time. I discovered my profession and I discovered my gender in one day. And it happened when my mom’s older sister was visiting us. And she is a professor, and so she was my motivation to become a professor. And at the same time, I realized, oh, I’m a girl. And at the time, I didn’t think much of it. I’m four years old, and I just figured this is something that happens to everyone. And as I got a little bit older, I start to realize that I didn’t just feel like a girl, but that I kind of fit somewhere in between. And again still assumed this is how everyone felt. And by the time I was starting middle school, I realized, oh, this is pretty unique. And I have to admit that, at the time, because I identified more as a girl, I was hoping that puberty would give me a different body than I have right now and that I would end up having a girl body to go along with my sense of being a girl gender.

And again, at the same time, we didn’t have the language to be able to explain that, and so it was really difficult for me to be able to convey to other people what I viewed as my gender. And it was difficult for other people to tell me what they viewed as. And so, kind of the Eureka moment was in an English class, we were talking about The Merchant of Venice and we were talking about Portia, and the teacher said, “So you have to consider Portia as being a girl in a boy’s body, acting like a boy.” I was like, oh, that’s me. And so that was essentially the point at which I realized, this is what my gender is. Yeah.

PV: So at the same time that you figured out what you wanted to do with your life, you figured out who you were as well. That’s a lot for being four.

JL: It was. And of course, just like my gender, my ideas of what I wanted to be professionally shifted over time. But ultimately, obviously, I ended up becoming a professor, and in fact, that was partly because of my gender identity. I wanted to pick a field where I would be able to be comfortable with the way I dressed, so I knew I couldn’t work in the business world, because I am not comfortable in a suit and tie. And I wanted to be able to work in a field that was less gender-biased, for lack of a better way of putting it, than most of the STEM disciplines. And botany, at the time, was a field that was more open and welcoming to people who were not male. And so that’s how I ended up, partly, as a botanist and how I ended up as a professor.

PV: Really. So that influenced your choice even within the sciences.

JL: Yes, very much so. And then one other part about that is I was really interested in plant reproductive biology because plants can be whatever they want. You can have male flowers, you can have female flowers. You can have plants that produce male flowers some years and plants that produce female flowers some years. You can have flowers that are both male and female. You can have flowers that are male and have other flowers that are male and female on the same plant. You can have plants that have female flowers and male flowers at the same time. I’m like, this is perfect. This is me.

PV: Wow. Okay. That’s amazing. So that’s, what an interesting… and obviously you’ve stuck with it. It’s worked well for you.

JL: It has.

PV: Yeah. What changed for you between 2011 and 2019?

JL: Good question. And I think two things really were what made me change, how I approached this. And one was we had a better sense of what terminology we could use to describe our experiences. And so the idea of gender fluidity, for example, that term became much more commonly used. People started to understand what it meant. And so people could start to use it to identify how they felt because other people would understand what it meant. So I think that was part of it. And another part of it was working with students who were concerned about representation. And I had a meeting with one of my grad students who was lamenting the lack of representation of certain groups. And I realized that I needed to do a better job of representing, that it wasn’t just enough for me to be supportive and to be effectively an ally. That because this is my experience, I needed to be my full self.

PV: Yeah. When was that?

JL: It was about six years ago now, around 2015.

PV: And how do you identify today?

JL: So as a biologist, I view gender from a non-binary standpoint. And obviously, I’m gender fluid, and so I fit within that category as well. But because when I was young, I didn’t identify with a specific gender, now I typically use the term either genderqueer or agender to identify myself.

PV: So I think there’s this assumption that if you feel, as you do, that you aren’t the gender that you are assigned at birth, that you would naturally gravitate towards transitioning, either with things like hormones or with surgery. You’re not interested in that, right?

JL: So I think for a lot of people who are trans in whatever way that they’re trans, transitioning is clearly a critical part of being who they are, right, being their full self. And gender affirmation surgery, clearly, is really important, and hormone therapy can be really important. I think for me because I don’t identify with a specific gender, it makes it difficult for me to decide what I would transition to. And because for me, the fluidity is, okay, so I’m feeling more like a girl today, or I’m feeling more like a boy today, that also makes it pretty difficult to decide what to transition to.

And then another aspect of it is that I’m already fairly androgynous in terms of my build, and so my face is fairly masculine and obviously my voice is fairly masculine. But if you look at the proportions and I’m trying to buy clothes, then women’s clothes actually fit me better than men’s clothes do. And so even before I was open and out, I mostly wore women’s running gear, for example, because women’s running gear just flat out fit me better.

PV: What’s it been like since you decided to be more open about your gender?

JL: So there’s been a lot of support, which has been really nice, and I feel for the most part very welcome. One of the interesting things for me was that, when I was younger, I would be teased a lot. And people assumed that my gender isn’t what was different, that it was my sexuality. And so I was called a fairy a lot when I was very young, and I was called a different F-word when I was older. And that was basically on a daily basis that I would get this. It was whenever I was out and people didn’t know me, I would get the F-word, and it’s like, oh, you think you’re so original. And what’s been interesting, since I started dressing more like how I feel about my gender, is most of those kinds of comments have stopped. I still get death threats, and riding on public transportation can be kind of challenging because you always get someone who’s looking at you like, you don’t fit in.

But for the most part, people have been really supportive, so it’s been really nice. And again, for me emotionally, it’s been much better. So I feel like I am being able to be my full self now, and I’m able to go about my day without worrying about how I look. And to be blunt, before I started dressing the way I dress now, every time I was out, I felt like, I look crazy. I look ridiculous. This is not who I am. Now I feel like whenever I go out, I’m like, I like how I look. I like that people see me this way. And so that’s been a big change as well.

PV: I’m sorry. I have to follow up on this. Death threats?

JL: Yeah. I get people riding on the train who, as they’re walking past, say things like, you’re an abomination, you should be killed, or you’re a Satan worshiper or whatever, right? And it’s kind of like with the F-word, it’s like, oh, you think you’re so original. So. And I actually have had people physically accost me. And so it goes beyond just words, but actually, physically accost me.

PV: And what about here at Fordham?

JL: So for the most part, people have been really supportive. It’s been really nice. It’s been a journey. And I say that because I realize for everyone around me, it’s been a journey as well, right? And so my transition, I try to do over a fairly… and when we’re talking about transition, of course, it’s not from a medical standpoint. It’s more as how I present or how I dress, it’s my hair length, it’s things like wearing makeup. And I realize that for a lot of people at Fordham who have known me for a long time, it is different. And so I realize that it’s been quite a journey for other people as well. And so I feel that my being able to be my full self is a testament to the fact that most of the people of Fordham are nurturing and encouraging about it and are supportive about it.

PV: Yeah. Yeah. That’s great to hear. That’s great to hear. I mean, it’s so disturbing to hear about these kinds of things. You talk about the public transit. There’s this idea that we hold ourselves to, in New York City, that we’re so enlightened, but you know that that’s not the case at all, in many settings with many people. So it’s disturbing to hear that, and I’m sorry to hear that. That can’t be easy, but at the same time, I can’t say I’m all that surprised.

JL: Yeah. And thank you. It is easier in New York, I feel, because New York is very much a you do your thing, I’ll do my thing kind of place, which I think is good in this kind of situation.

PV: That covers all the questions that I have formally written down.

JL: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

PV: There is one more though.

JL: Oh yeah, okay.

PV: That I’ve been thinking about, and that is to say your family. Is that something that you feel like you could talk about?

JL: Yeah. I’m willing to talk about that. My ex-wife and I are you get along… well, we co-parent our children pretty effectively. Our kids joke about us being essentially co-workers as parents because we both work together on it. And she’s asked how do I identify, because of course she sees me like this, just like everyone else does. And same answer, right. It’s just kind of like, I don’t really identify with a specific gender. And with my kids, a couple of my kids are queer, and they’re very comfortable with their queerness. And so I, in some ways I feel like that, again, it’s this idea of representation, that for me to be my full self is good for them, because it lets them know that there are people even in our family that are supportive.

PV: Talking with Professor Lewis gave me a great local perspective on the subject. So, for my next interview, I decided to expand beyond our borders. Sameena Azhar, an assistant professor at the Graduate School of Social Service works with Khawaja sira, a group of third gender people who have lived in communities in Pakistan since the 16th century. Did I say that right?

Sameena Azhar: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

PV: I did. Khawaja sira.

SA: Khawaja sira.

PV: Just rolls right off your tongue. Yeah.

SA: Yeah, yeah. And the accent is for the a, on the A at the end, so Khawaja sira.

PV: Sira. Oh, okay.

SA: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah.

PV: So now, in my intro, I noted that in the United States, you can now pick a third gender on official documents. That’s old news in South Asia though. Why?

SA: Well, it’s not super old. In 2014, the Supreme Court of India allowed for the creation of a third gender. So rather than registering as an M or a male, or a F as a female, you can register as an E. So this third gender option. And similar policies have also been passed in Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, not in Sri Lanka and Afghanistan, but the rest of those South Asian countries passed similar policies. Additionally, in India, Hijra are considered a scheduled caste.

So the scheduling of castes and tribes in India is a process that dates back to colonialism, and there were certain groups of people or communities that were considered to be scheduled as caste or tribes. And these individuals in modern India get a sort of affirmative action-style status by the government. So there are social entitlements that are available to them that are akin to welfare or food stamps, allotted seats in the representative government at the local level, so they’re called panchayats, so they’re reserved seats for people that are from these communities. So they’re pretty progressive actions to try to include these folks who are fully socially within South Asian society. And it’s a community that has been really gripped by both a long history of being honored and exalted, and also a long history of being marginalized.

PV: Now, I just spent a lot of time talking about the Khawaja sira and getting that correct, but you just referenced another group in India.

SA: Yeah. So, I mean, we’re basically talking about more or less the similar identities of third gender and gender-nonconforming identities. In India, the nomenclature is most commonly called Hijra.

PV: Hijra.

SA: Right. There’s other names for it in India as well, like Kinnar, Khusra, Aravani. There’s many names for this. In Pakistan, the name is Khawaja siras.

PV: What does colonialism have to do with all of this?

SA: So prior to British colonization, under mogul or Raj, but control, there was much more state-sanctioned support for these communities. So folks who were hijra or Khawaja sira would often work as courtesans or advisors or handmaidens in the royal court. And with the coming of colonization, the identity of being a hijra became criminalized. So in 1871, the Criminal Tribes Act made hijra criminals. And then additionally, Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which is borrowed from the British penal code, criminalizes what is called carnal intercourse against the order of nature. Right? So this essentially is interpreted to be homosexuality or more specifically sodomy.

PV: When you talk about these folks that embrace this way of being, are we talking about people who would typically be identified as male embracing femininity or vice versa?

SA: No, typically it is folks who’ve been assigned male sex at birth and identify as either women, or as men and women, or as a third gender person. It’s much less typical, I mean, pretty much, for the most part, doesn’t exist, to have somebody who was assigned female sex at birth, who may identify as a man and be called a hijra. So it is quite specific to what we would call in the West, trans women. But the third gender classification of E does encompass anyone, regardless of whatever sex was assigned at birth, to identify as E.

PV: And how does this all relate to what you do here at Fordham?

SA: So my research really began in south India. My family is from a city called Hyderabad. It’s where I did my dissertation research, so mainly looking at issues related to HIV and gender non-conformity stigma of people who are living with HIV, are HIV positive. And my work in Pakistan has been somewhat of an extension of that. I’m not focusing there on folks who are HIV positive. There’s also a much, much lower prevalence of HIV in that part of Pakistan, so my research there is focused on an area called Swat, which is in Khyber Pakhtunkhwaqua, and that is the northwest province that borders Afghanistan.

So it’s been a very interesting place to be doing research, first through the pandemic, but also through the huge influx of Afghan refugees that have come in the past several months. The focus of those interviews and surveys that we’ve been conducting in both India and Pakistan have been really around trying to figure out how to reduce these experiences of the stigma that people are encountering within their families, within their communities, within employment settings, within healthcare settings, knowing that these experiences contribute also to poor mental health, and most probably acutely to experience the violence or homicide against gender-nonconforming people.

So one of my participants, research participants in India had been murdered during our research, and it really just drives home that these are issues that impact people’s lives in very intimate and violent ways.

PV: Yeah. Yeah. Oh, man, that’s brutal.

SA: Yeah, yeah. Truly was.

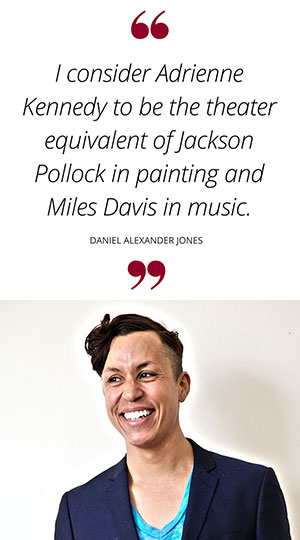

PV: Daniel Alexander Jones, a professor of theater who performs under the stage name Jomama Jones, first introduced me to the concept of gender fluidity when I met him in 2013. Now, Daniel, Jomama has been a vehicle for you to try to get people to see both themselves and others in a new light. Do you feel like you’re seeing some of the changes you were hoping for?

Daniel Alexander Jones: Oh, Patrick. That’s a good question. Yeah. I think were you to look at maybe 2010 and look forward at where we seemed to be heading as a nation, we’ve gone in a very different direction.

PV: Do you feel like there’s been a backlash?

DJ: There are people who believe their way of life is threatened by the changes that are happening, or even by, and this may be a more accurate way to say it, the naming of things that have always been there, but the taking up a space around those things, right? We know that those we call trans folk now have always been here, throughout history. This is not a new phenomenon, but it is culturally shaped in such a way that claiming sovereignty and truth and ownership of that identity is going to be a threat to someone for whom that identity’s invisibility is necessary for them to understand themselves, for them to feel their own sense of power, right? When you think about how that’s connected to the last five or six years of our national experience, it’s sobering.

PV: The last time we talked, you said that so much of the conversation about gender fluidity is about how we encounter someone who is different from ourselves, and what happens to us if we fully accept them. Can you elaborate a little bit on that?

DJ: This was originally, Patrick, from my perspective as an artist, because I was thinking about, both in my work professionally and also in the classroom, what role curiosity plays. The idea of engaging something you don’t know and being heightened or quickened or energized by the unknown, as much as you are by the process of naming and pointing out the things that you do know. And for an artistic process, whether it be writing or acting or directing, whatever the thing is, vital work depends on that curiosity. And it is that destabilization and the reaching for language to articulate what you’re feeling, the comparison of this new feeling to things you have experienced before. And also, if you will, the surrender into the possibility that that new experience has. All of those things are so necessary.

And what I began to encounter in the classroom, and what I began to encounter professionally even more so, was this sense of, we’ve got to name it and know it. What the problem is rooted in is a kind of taxonomical approach to life. Meaning that, if we think about taxonomy, we think about this idea of naming, delineating, putting things into categories. I’m thinking very often of those butterfly cases. Like those, the people who go out and collect them, and they pin the butterfly, and they name the butterfly, and there’s a sense that it is that thing. But we know that butterflies in life move. What they came from you don’t get in that pinned creature. So there’s so much of the story that’s missing from that pinned moment in time.

And then too, we then begin to think about exemplars of a particular group. Like this is what this type of thing looks like. And the connected part of that is we then begin to assume that something that looks like that, that has the same shape or form or the same name, will have the same content. Why? Well, in part we know it’s because our brain wants to filter out the things that are familiar so that we can pay attention to the things that aren’t. But I think the artist has a responsibility to deliberately engage what we don’t know, to deliberately destabilize what we think we know. It is part of our social responsibility.

And I think one of the things that this question around gender fluidity rubs at is that, if we live in a culture that has defined gender according to these formal shapes, whether they be shapes of thought or shapes of material of the body, we then eliminate the content. And that subjective content is the truth for that individual. So what does it mean that we would center a process by which I can have my observations, but I can’t then overwrite my truth of what those observations mean onto you before I get to know who you are, before I hear from you. Because as is so often the case, especially with folk who are dealing with expressing their own gender fluidity, very often what’s on the inside doesn’t match, quote-unquote, what’s on the outside. And so if I come to you and I have determined your interior by your outside, then I have done a violence to you.

PV: Talk to me about your own journey. How has your act changed since you started?

DJ: I was born into and raised in a worldview that was so profoundly shaped in the macrocosmic way by the civil rights movement, like the freedom movement and the workers’ movement, the grassroots movements that created the community I grew up in. Also, the courage of my parents who had an interracial marriage at a time where that was really forbidden, and the power of my community, which was a black community, working-class in western Massachusetts, that also was the house for a kind of multiethnic enclave. All of that to say that the culture that was born from that mixture of people, and that particular time, was in many ways set in opposition to the world that I entered when I started to go to school, which was a hierarchical world where race had a hierarchy, gender had a hierarchy, class for sure had a hierarchy.

So I had very early on to learn that I knew things about life that many of the people that I was going to meet in this other world didn’t know. And I also had to understand from a very early age, and I’m talking about memories from kindergarten, first grade, second grade, that many of the stories that were in that new world about who I was, about who my parents were, about who the people I loved were, were false. And I had to have the inner resolve, even before I had language to articulate it, to say, that’s not true. They don’t know.

And it’s when I became aware of my sexuality, and I understood that I was gay. What I understood is, just like I talked about those two different worlds, I could also look and say, oh, this is what is posited as being a boy or a girl or a man or a woman or… I could look at what the rules were supposed to be. So again, I came into this all at a time when I was looking around and saying, oh, wow, everybody’s playing this game. Everybody’s adopting these roles. And this person that I’ve known my whole life is now suddenly a jock or a girly girl or whatever. And I’m like, oh, it’s so interesting to see the person I know, take on and perform an extreme version of gender, as a way to get power, as a way to find their security, as a way to name themselves and be part of this larger configuration of students in this public high school.

And I knew it wasn’t me. So if I don’t fit any of these things, then the pressure, which I think is what a lot of young people face, is how do you conform? How do you figure out how to get access to or move in that system? Or the real danger, how are you taking that in, like do you try to fight your way back into the thing? And maybe the blessing and the curse that I had was like I told you, I had an experience and a bodily experience of something else.

One of the things that’s interesting, I’ve been teaching at this Jesuit university, and I hear a lot about the teachings of Christ. And I think one of the primary ideas is that you greet strangers as holy presences, that who you don’t know may be an angel. It’s your responsibility to take care of your fellow human being. Care means presence. Are you willing to be present with another human being? And I’m shocked always by how many people are unwilling to do that. I shouldn’t be shocked, but I remain shocked.

PV: Talking to Daniel shed light on how the culture is changing, but of course, culture can’t thrive if it’s not given the space to do so, which is the realm of law. For that, I turn to Elizabeth Cooper, a professor of law and the faculty director of the Feerick Center for Social Justice at Fordham Law School. Now you were involved in the passage of the Gender Expression Non-Discrimination Act or GENDA, a 2019 New York law that was originally part of a previous law that was passed in 2002.

Elizabeth Cooper: I have had the real pleasure of being a member of and an advocate for the LGBTQ communities for many decades. And I remember very clearly when we were trying to get the Sexual Orientation Non-Discrimination Act, otherwise known as SONDA, passed through the state legislature. And there were a number of advocates that were trying to get the bill passed in its original form. And that would’ve prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation, which is being lesbian, gay, bisexual, as well as on gender expression or identity. And those phrases typically refer to people who are transgender or gender non-conforming. The advocates were told that they could get SONDA passed, but only if they took out the protections for gender expression.

And the advocates agreed to do that with the notion of, we’ll come back next year, get the gender expression non-discrimination provisions passed. Well, it just so happened that SONDA was passed in 2002, became effective in early 2003, but it was not until 2019 that the Gender Expression Non-Discrimination Act actually was enacted. The law is so powerful, because it prohibits discrimination on the basis of gender identity or expression in employment, in housing, in places of public accommodation, in education, in countless areas, basically adding gender expression and identity to the long list of identities that cannot be the basis for discrimination in New York State.

PV: When it comes to the push and the pull of these laws, you’ve said that Jim Crow laws can be a helpful reference point. Can you explain why?

EC: If you think about Jim Crow laws or Title VII, which prohibits discrimination in employment, or the Americans with Disabilities Act, which prohibits discrimination on basis of disability, you have lots of prohibitions on discrimination based on an individual’s identity, their core identity, who they are. Historically, I think the Supreme Court often thought of these as immutable characteristics. Not all of them are so immutable, but they are basically aspects of identity that go to one’s core. They also have absolutely no impact on how well one can perform one’s job. So if you have a person who is an excellent lawyer, for example, it should not matter whether they are transgender or cisgender, meaning that their physiology and their gender identity aligns, cisgender. And so, why should we permit discrimination based on gender identity? It makes absolutely no sense. This has nothing to do, like race, like sex, like religion, with how one can do one’s job.

I think that thinking about this historical context is also helpful when we start to think about the ways in which some people argue that religion or biblical values mean that one should be able to discriminate against people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, gender non-conforming, and so on. It’s important to look historically to the kinds of arguments that were raised against Title VII and other laws that prohibit discrimination based on race. For example, people argued that it would be wrong to have black people and white people in the same bathroom, that it went against the Bible, that there were risks of violence. There were people who argued that separation of the races was mandated by the Bible. And in this context, I think that we are getting to the point where we understand that gender identity or expression or sexual orientation, this is not a matter of choice or going against God or going against the Bible. This is just a matter of who we happen to be.

PV: It seems like people either are willfully ignoring history or just don’t know about it.

EC: I think most people don’t know about it. I think that the point is just to look at people for the value of, for example, employment, the job that they can do. Why would you ever want to tell someone who’s gender non-conforming that they can’t walk into a movie theater? Or why would it be okay or should it be okay for a doctor to say to a transgender person, I don’t want to treat you?

PV: You’ve been involved in this advocacy for 25 years with groups such as the law school’s LGTBQ student group. How have things changed within the movement itself in that time?

EC: I confess that I am just dumbfounded by the changes that have happened in my lifetime. And when I say dumbfounded, I mean in the best way possible. When I first started teaching at Fordham, I was concerned about coming out. I remember that the LGBT law student group sometimes met off-campus, so its members would not have to worry about being seen walking into a room where people knew that the gay group was meeting.

The attitude today towards lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, gender identity more generally, is just striking. I see law students and undergrads. I have a niece who’s 18 years old. I see her and her peers having a comfort with people who are different from themselves. And they don’t look at it as something that should require segregation. They look at it as something to learn about, and they want to embrace the richness of diversity in their lives. So you have straight people, like my niece, joining the high school Gay-Straight Alliance. You have kids coming out as teenagers in high school, sometimes middle school. You have people claiming their gender identity or presenting themselves in gender non-conforming or genderqueer ways much earlier on.

There is a real, tangible move away from understanding gender as a binary. There is a much greater acceptance, understanding and acceptance, that gender, like race, is very socially constructed. It’s not that men don’t typically have more testosterone and women typically have more estrogen, or we have different body parts, but that, in the way we present ourselves, some of our rules are arbitrary. Why should only women wear nail polish? Why should only women wear dresses? Why should only men wear ties and Oxford shoes, right? It has nothing to do with who you are and your core values as a human being. If anything, how much more wonderful this world is when people can be their full selves and live their full lives, whether it is with their families of origin, or in the workplace, or walking down the street in the middle of New York City or the middle of any other small town, anywhere in this country.

]]>

This fall, the One Flea Spare Project brought together faculty and students from five universities—Fordham, the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Princeton University, Georgetown University, and SUNY Purchase—for shared projects, workshops, and classes, based on themes raised in the play. Set in London at a time when the city was beset by plague, the play revolves around a wealthy couple who is preparing to flee their house but are instead forced to quarantine for 28 days with two strangers who’ve snuck into their home.

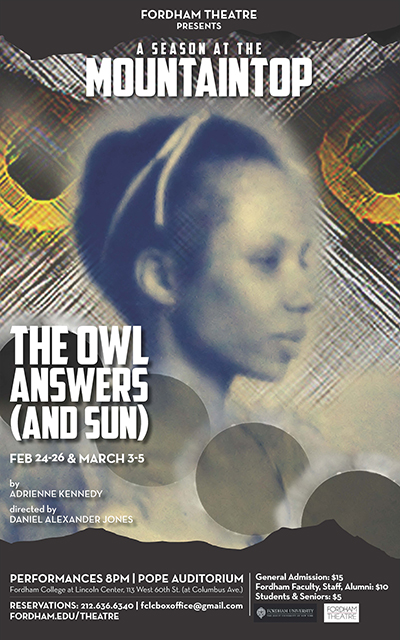

In November, One Flea Spare’s creator, Naomi Wallace, participated in a webinar for the project for all of the universities involved, and this semester, she led a two-week playwriting workshop connected to the playwriting class that Fordham’s Daniel Alexander Jones teaches.

“What’s so brilliant about Naomi is that she has meditated on the human condition, and how we behave when we’re in quarantine, particularly around our own mortality and how relationships change when death is literally at your door,” said Ramos, noting that the interdisciplinary nature of the project expanded the reach of theater education.

“It was just an obvious choice. Everything in the play sort of parallels what we’re going through now.”

Beyond Theater Classes

The concept behind the project was simple. If a professor was teaching an online class in any discipline that addressed how plagues and pandemics affect literature and art, they could open it up to any student attending the participating universities. A student at Fordham could attend The Great Work Begins: Revisiting Angels in America During a Pandemic, which was offered at Georgetown in the fall, while a student at SUNY Purchase could attend Texts & Contexts: Plagues and Poxes, a course taught by Fordham’s Rebecca Stark-Gendrano, Ph.D. Professors were encouraged to include One Spare Flea in the syllabus for their classes; the majority of them did so.

This semester, the project’s major focus has been A Passage in Relief, a collaborative, virtual theatrical response to One Flea Spare being spearheaded by Princeton University’s Elena Araoz that will take place on April 26.

Wallace, who participated from London, called the project exhilarating.

“How students, artists, and writers read and see and perform my work is an education and a delight,” she said.

‘Imaginative Solidarity’

“One of the things that the One Flea Spare Project at Fordham inspired me to do was reformulate my theories about teaching and writing, as with the idea of ‘imaginative solidarity,’” Wallace said.

“Imaginative solidarity” was the focus of Wallace’s recent virtual workshop, which brought together students from the five universities on March 25 and April 1. She described it as a process of engaging in a dialogue with history and uncovering “the workings of U.S. racial capitalism and its long and ugly history of colonial dispossession and racial slavery.”

“This is about challenging our imaginations to break down the binaries between domestic and ‘foreign’ events, between what is happening in the United States and what our government is up to elsewhere,” she said.

Daria Kerschenbaum, a Fordham College at Lincoln Center senior majoring in English and theater, said the workshop helped her with her final project, a play about Edgar Allen Poe’s child bride, Virginia.

Acknowledging the Ghosts of History

As part of the workshop, Wallace asked students to research recent U.S. military campaigns; Kerschenbaum was tasked with researching the 1986 bombing campaign of Libya. Key to the exercise was exploring a sense of empathy for those who were on the receiving end of the bombs.

“I think talking with Naomi gave me a good perspective about how empathy is so important to creating diversity in entertainment,” said Kerschenbaum, who is in Fordham Theatre’s playwriting track.

“Social justice is remembering the ghosts of what has happened in our country and being able to acknowledge them and be in dialogue with them,” she said.

Kerschenbaum collaborated with Percival Hornak, a first-year graduate student at UMass Amherst who is supervising the construction of an interactive “lobby display” that can be viewed before and after the presentation of A Passage in Relief.

Expanding Community During Isolation

Hornak said a play about plagues gave him pause at first but collaborating with students at other universities has been very fulfilling.

“This past year, I’m not encountering as many people as I would; just people I’m in class with and people I work with. It’s been really nice to expand the people I interact with and embrace all these different universities’ approaches to teaching and to making theater,” he said.

The project was funded by an Arts and Science Deans’ Faculty Challenge Grant” for $9,703, but the job of pulling it all together fell to Emma McSharry, a senior pursuing design and production in the theater department.

“It’s been a lot of logistics, which is more difficult over Zoom and email, but that’s what I’ve been trained to do for the last three years, so I was ready,” she said laughing.

Ramos said the success of the project proved that people are really interested in reaching out to others, and he said he hopes that energy doesn’t dissipate when life begins to return to something resembling the past.

“There was an openness during the pandemic that I don’t think we’ve experienced before, and I think there’s a sense that when we come back in the fall, we’re all going to go back indoors and, in a way, we will be subject to those walls again,” he said.

“This confirmed that everyone really needs community.”

]]>

“Today’s events are designed for recognition, celebration, and appreciation of the numerous contributors to Fordham’s research accomplishments in the past two years,” said George Hong, Ph.D., chief research officer and associate vice president for academic affairs.

Hong said that Fordham has received about $16 million in faculty grants over the past nine months, which is an increase of 50.3% compared to the same period last year.

“As a research university, Fordham is committed to excellence in the creation of knowledge and is in constant pursuit of new lines of inquiry,” said Joseph McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, said during the virtual celebration. “Our faculty continue to distinguish themselves in this area. Today, today we highlight the truly extraordinary breadth and depth of their work.”

Earning Honors

Ten faculty members, representing two years of winners due to cancellations last year from the COVID-19 pandemic, were recognized with distinguished research awards.

“The distinguished research awards provide us with an opportunity to shine a spotlight on some of our most prolific colleagues, give visibility to the research achievements, and inspire others to follow in their footsteps,” Provost Dennis Jacobs said.

Recipients included Yuko Miki, associate professor of history and associate director of Latin American and Latinx Studies (LALSI), whose work focuses on Black and indigenous people in Brazil and the wider Atlantic world in the 19th century; David Budescu, Ph.D., Anne Anastasi Professor of Psychometrics and Quantitative Psychology, whose work has been on quantifying, judging, and communicating uncertainty; and, in the junior faculty category, Santiago Mejia, Ph.D., assistant professor of law and ethics in the Gabelli School of Business, whose work examines shareholder primacy and Socratic ignorance and its implications to applied ethics. (See below for a full list of recipients).

Diving Deeper

Eleven other faculty members presented in their recently published work in the humanities, social sciences, and interdisciplinary studies.

Jews and New York: ‘Virtually Identical’

Images of Jewish people and New York are inextricably tied together, according to Daniel Soyer, Ph.D., professor of history and co-author of Jewish New York: The Remarkable Story of a City and a People (NYU Press, 2017).

“The popular imagination associated Jews with New York—food names like deli and bagels … attitudes and manner, like speed, brusqueness, irony, and sarcasm; with certain industries—the garment industry, banking, or entertainment,” he said. “

Soyer quoted comedian Lenny Bruce, who joked, “the Jewish and New York essences are virtually identical, right?”

Soyer’s book examines the history of Jewish people in New York and their relationship to the city from 1654 to the current day. Other presentations included S. Elizabeth Penry, Ph.D., associate professor of history, on her book The People Are King: The Making of an Indigenous Andean Politics (Oxford University Press, 2019), and Kirk Bingaman, Ph.D., professor of pastoral mental health counseling in the Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education, on his book Pastoral and Spiritual Care in a Digital Age: The Future Is Now (Lexington Books, 2018).

Focus on Cities: The Reality Beyond the Politics

Annika Hinze, Ph.D, associate professor of political science and director of the Urban Studies Program, talked about her most recent work on the 10th and 11th editions of City Politics: The Political Economy of Urban America (Routledge, 11th edition forthcoming). She focused on how cities were portrayed by the Trump Administration versus what was happening on the ground.

“The realities of cities are really quite different—we’re not really talking about inner cities anymore,” she said. “Cities are, in many ways, mosaics of rich and poor. And yes, there are stark wealth discrepancies, growing pockets of poverty in cities, but there are also enormous oases of wealth in cities.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Hinze’s latest edition will show how urban density did not contribute to the spread of COVID-19, as many people thought, but rather it was overcrowding and concentrated poverty in cities that led to accelerated spread..

Other presentations included Nicholas Tampio, Ph.D., professor of political science, on his book Common Core: National Education Standards and the Threat to Democracy (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018); Margo Jackson, Ph.D., professor and chair of the division of psychological and educational services in the Graduate School of Education on her book Career Development Interventions for Social Justice: Addressing Needs Across the Lifespan in Educational, Community, and Employment Contexts (Rowman and Littlefield, 2019); and Clara Rodriguez, Ph.D., professor of sociology on her book America, As Seen on TV: How Television Shapes Immigrant Expectations Around the Globe (NYU Press, 2018).

A Look into Migration

In her book Migration Crises and the Structure of International Cooperation (University of Georgia Press, 2019), Sarah Lockhart, Ph.D. assistant professor of political science, examined how countries often have agreements in place to manage the flow of trade, capital, and communication, but not people. While her work in this book specifically focused on voluntary migration, it also had implications for the impacts on forced migration and the lack of cooperation among nations .

“I actually have really serious concerns about the extent of cooperation … on measures of control, and what that means for the future, when states are better and better at controlling their borders, especially in the developing world,” she said. “And what does that mean for people when there are crises and there needs to be that kind of release valve of movement?”

Other presentations included: Tina Maschi, Ph.D., professor in the Graduate School of Social Service, on her book Forensic Social Work: A Psychosocial Legal Approach to Diverse Criminal Justice Populations and Settings (Springer Publishing Company, 2017), and Tanya Hernández, J.D., professor of law on her book Multiracials and Civil Rights: Mixed-Race Stories of Discrimination (NYU Press, 2018).

Sharing Reflections

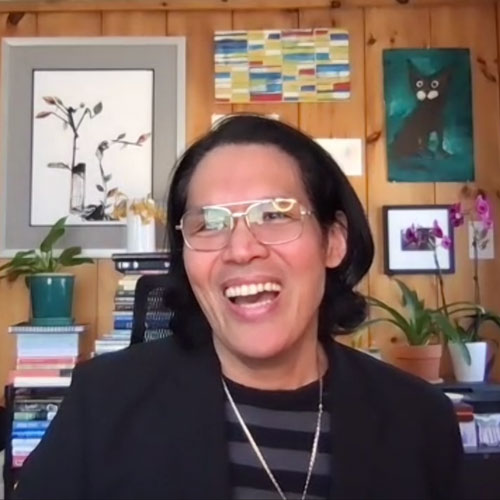

The day’s keynote speakers—Daniel Alexander Jones, professor of theatre and 2019 Guggenheim Foundation Fellow, and Tony Award winner Clint Ramos, head of design and production and assistant professor of design—shared personal reflections on how the year’s events have shaped their lives, particularly their performance and creativity.

For Jones, breathing has always been an essential part of his work after one of his earliest teachers “initiated me into the work of aligning my breath to the cyclone of emotions I felt within.” However, seeing another Black man killed recently, he said, left him unable to “take a deep breath this morning without feeling the knot in my stomach at the killing of Daunte Wright by a police officer in Minnesota.”

Jones said the work of theatre teachers and performers is affected by their lived experiences and it’s up to them to share genuine stories for their audience.

“Our concern, as theater educators, encompasses whether or not in our real-time lived experiences, we are able to enact our wholeness as human beings, whether or not we are able to breathe fully and freely as independent beings in community and as citizens in a broad and complex society,” he said.

Ramos said that he feels his ability to be fully free has been constrained by his own desire to be accepted and understood, and that’s in addition to feeling like an outsider since he immigrated here.

“I actually don’t know who I am if I don’t anchor my self-identity with being an outsider,” he said. “There isn’t a day where I am not hyper-conscious of my existence in a space that contains me. And what that container looks like. These thoughts preface every single process that informs my actions and my decisions in this country.”

Interdisciplinary Future

Both keynote speakers said that their work is often interdisciplinary, bringing other fields into theatre education. Jones said he brings history into his teaching when he makes his students study the origins of words and phrases, and that they incorporate biology when they talk about emotions and rushes of feelings, like adrenaline.

That message of interdisciplinary connections summed up the day, according to Jonathan Crystal, vice provost.

“Another important purpose was really to hear what one another is working on and what they’re doing research on,” he said. “And it’s really great to have a place to come listen to colleagues talk about their research and find out that there are these points of overlap, and hopefully, it will result in some interdisciplinary activity over the next year.”

Distinguished Research Award Recipients

Humanities

2020: Kathryn Reklis, Ph.D., associate professor of theology, whose work included a project sponsored by the Henry Luce Foundation on Shaker art, design, and religion.

2021: Yuko Miki, Ph.D., associate professor of history and associate director of Latin American and Latinx Studies (LALSI), whose work is on Black and indigenous people in Brazil and the wider Atlantic world in the 19th century.

Interdisciplinary Studies

2020: Yi Ding, Ph.D., professor of school psychology in the Graduate School of Education, who received a $1.2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education for a training program for school psychologists and early childhood special education teachers.

2021: Sophie Mitra, Ph.D., professor of Economics and co-director of the Disability Studies Minor, whose recent work includes documenting and understanding economic insecurity and identifying policies that combat it.

Sciences and Mathematics

2020: Thaier Hayajneh, Ph.D., professor of computer and information sciences and founder director of Fordham Center of Cybersecurity, whose $3 million grant from the National Security Agency will allow Fordham to help Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Minority-Serving Institutions build their own cybersecurity programs.

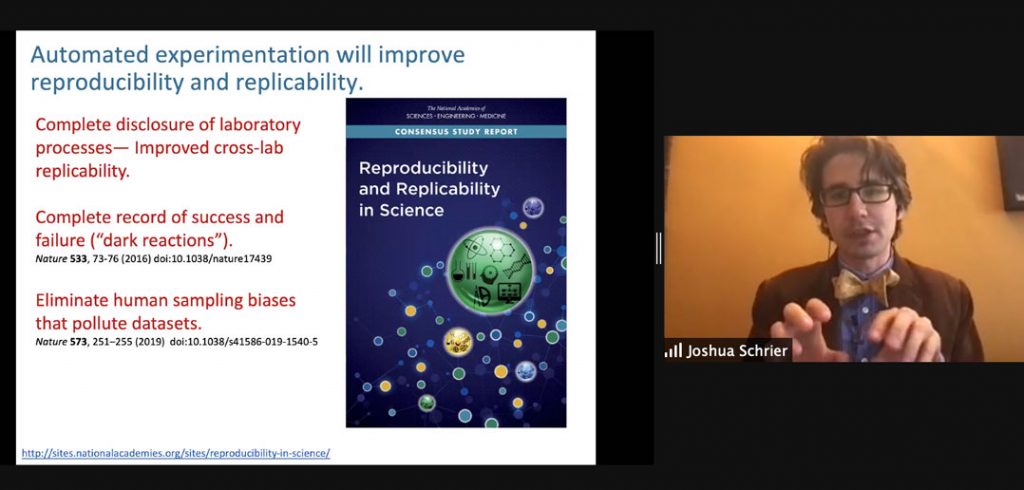

2021: Joshua Schrier, Ph.D., Kim B. and Stephen E. Bepler Chair and professor of chemistry, who highlighted his $7.4 million project funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency on perovskites.

Social Sciences

2020: Iftekhar Hasan, Ph.D., university professor and E. Gerald Corrigan Chair in International Business and Finance, whose recent work has included the examination of the role of female leadership in mayoral positions and resilience of local societies to crises.

2021: David Budescu, Ph.D., Anne Anastasi Professor of Psychometrics and Quantitative Psychology, whose work has been on quantifying, judging, and communicating uncertainty.

Junior Faculty

2020: Asato Ikeda, Ph.D., associate professor of art history, who published The Politics of Painting, Facism, and Japanese Art During WWII.

2021: Santiago Mejia, Ph.D., assistant professor of law and ethics in the Gabelli School of Business, whose work focuses on shareholder primacy and Socratic ignorance and its implications to applied ethics.

And indeed, if you sign up for these classes, Jones, a member of the faculty since 2008, will artfully guide you through your paces in these aspects of stagecraft.

If, however, you visited the Connelly Theater, Joe’s Pub, or any of the myriad theaters where Jones has performed over the last decade, you’d have encountered a very different person: Jomama Jones.

Since her debut in 2011, Jomama, a radiant soul diva with her own distinct backstory and career, has been a vehicle for Jones to explore profound questions of race and gender. In 2011, the New York Times described Jomama’s performance as “glowing, making it hard not to surrender to this sequin-encrusted earth mother’s soulful embrace.” In 2015, Jones won a Doris Duke Artist Award, which featured a $225,000 unrestricted, multiyear grant, and this April, he was honored with a Guggenheim Fellowship.

In addition to critically acclaimed performance pieces such as Black Light, which he performed at the Public Theater and Greenwich House Theatre, and Duat which he performed at Soho Rep, Jones has also produced plays such as Phoenix Fabrik, Bel Canto, Ambient Love Rites, and Earthbirths, Jazz and Raven’s Wings, and five albums of original songs.

So what has Jomama been up to these days? In a new podcast, Fordham News tracked Daniel down to find out.

And in a bonus track, Jones explains what the term Afromystical means, and why it’s so important to understanding “Jomama Jones.”

Full transcription below

Patrick Verel: If you visit the Fordham Theater Program’s webpage, you’ll find classes with titles such as acting, theater history, flying solo, and young, gifted and black, all offered by one Daniel Alexander Jones. And indeed, if you sign up for these classes, Jones, a member of the faculty since 2008, will artfully guide you through your paces in these aspects of stagecraft. If however, you visited the Connolly Theater, Joe’s Pub, or any of the myriad theaters where Jones has performed over the last decade, you’d have encountered a very different person, Jomama Jones.

Since her debut in 2011, Jomama, a radiant soul diva with her own distinct backstory and career, has been a vehicle for Jones to explore profound questions of race and gender. In 2011 the New York Times described Jomama’s performance as quote, “Glowing, making it hard not to surrender to the sequin encrusted earth mothers soulful embrace.” And in 2015 Jones won a Doris Duke artist award, which featured a $225,000 unrestricted, multi-year grant.

So what has Jomama been up to these days? Fordham News tracked down Daniel to find out.

So when we met in 2013 you told me, and I quote, “I think terror and art go hand in hand. If you’re not scared, you’re not doing it right.” So 2019 must be a phenomenal time to make art, right?

Daniel Alexander Jones: Yes, indeed.

PV: Tell me about it. How is it making art in 2019?

DAJ: Yeah, well that that idea of fear and its relationship to creating is an important one in that. I think it’s always important to feel what I call a quickening. Like when your heart races a little bit fast. There are a lot of states of mind and states of being that can bring us to that place. Love can bring us to that place. Curiosity can bring us to that place. Fear can bring us to that place. But all of it is for me about getting beyond your comfort zone. The habits that you have, the ways that you are accustomed to doing things. And when you move past that and you get into that place where you get a little bit afraid, your instincts kick in in a different way. And I think you start to see things with more acuity and you start to listen with more specificity. And that means you’re paying attention. And if there has ever been a time in my adult life in the United States of America where we need to be paying attention, it’s now.

Using the arts to explore possibility is a real honor, but it’s also one of the most powerful places to be working because it is about accessing the imagination. And if we cannot imagine what comes next, we can’t manifest what comes next.

PV: Talk to me about Waves, which I understand is a book you’re working on. It’s a book of creative nonfiction and you’re doing live readings of now.

DAJ: For the last three summers I’ve been dedicating my time to crafting this manuscript. I finished it in late August and gave it to my editor who just gave me back my manuscript. So the remainder of this year is dedicated to getting back in there and refining it. But I set out to write and collect the work that I had done for theater performance, techs, plays, which largely had not been published. And a number of friends and colleagues who said, “Yo, you got to publish your stuff.” And I said, “All right, I’ll sit down and I’ll do this.” And as I looked at the different work that I’ve made over the last 25 years, I said, anybody coming to this work not having seen it firsthand or not knowing me, would not probably be able to put it in a context because it’s kind of all over the place, in a way that I’m happy with, but it taps into a number of different ways of making work and different styles.

So I said, let me write a little contextual essay so that it’ll frame this work. And when I sat down to write that essay, that essay exploded into its own project. What I recognized was that I had a deep need to write about lineage. To write about the artistic traditions out of which my own work comes, in which I participate, hopefully which I extend, and which for sure here at Fordham forms the basis of what I teach.

So that meant that I was writing this kind of hybrid of memoir stories about and kind of essays about the mentors that I had in the arts, most of whom were pretty extraordinary black women who came out of either or both the avant garde black American theater tradition and or queer theater traditions. And then also to write about what it meant to integrate the lessons that they taught me into everyday life and everyday practice.

PV: Who’s one that you would think would be good to mention for this?

DAJ: Yeah. I will mention one who actually, it’s very interesting, her name was Dr. Constance Berkeley. Dr. Berkeley was one of my professors in undergrad when I went to Vassar College. I write at length about her and the many lessons she taught me, and particularly about her ability to help me understand better what it means that we live in a society that is so deeply informed by racism, classism, a kind of cultural imperialism that erases the truths of all of our distinctions as human beings. And that’s everybody in the society. And what it means to engage that means that you have to become an extraordinary observer, an extraordinary listener, and someone who can ask really good questions. Because if you make a space where you ask the right kinds of questions, people can reveal the complexity and the nuance of who they are outside of these very rigid, binary and hierarchical systems.

Her argument was everybody is so much more than the categories that they were reduced to. Everybody. And it is our work to take the time and the energy to see one another and to be with one another in that nuanced way. It’s harder. It takes more courage, and it takes more time. And especially in a society where everything moves at such a clip and our assumptions become our certainties and those certainties become things that are a part of that comfort zone I was talking about. The way we can navigate the world, certain of who does this, what that is. You can’t be in the arts, I don’t think, and be true to the work if you’re not willing to engage uncertainty and discomfort and the unknown.

PV: Have you visited many places that might be a little more resistant to this kind of performance?

DAJ: Absolutely. Yeah, and I think that’s actually a very big part of what’s important about making this kind of work. With touring Jomama, we’ve had a number of experiences where we’ve been places that had never experienced anything like Jo and have maybe not experienced a show like a show that I make and there’s been a lot of power in that for all involved.

I’m thinking of one time in particular we brought one of the shows to rural Minnesota, to this town that was definitely the red part of the state. I think a lot of folks who came to the show had seen the poster and they thought Jomama was real, which she is, but they didn’t understand that there was a male identified person portraying this person. And it was intense. And you could see there was a moment of, oh my God. And some people had brought their children. There was a lot of, oh my goodness. And then on top of that, the kinds of things I was talking about were very challenging. What happened was that people stayed the course.

And I think because of what I was mentioning, that I’m really interested in the encounter, the experience of being in the space together. And as Dr. Berkeley taught me, I really want to see who you are and I want you to see who we are and be in the space together. There’s not a trick and I’m not here to attack or shame you. I’m here to be. To talk about these ideas. And my ideas may confront you. I may confront you, you may confront me. But if we can stay in the heat with one another, what might be possible? Because the typical thing to have happen is you get into those highly charged situations and people decamp to their certainty. And this I deal with as a professor all the time. It’s like how do you have a dialogue in a classroom where people’s ideas are so fixed? How do you have a conversation?

PV: Right. So in a way you actually bring your teaching experience to the stage.

DAJ: And vice versa.

PV: And vice versa.

DAJ: 100%. 100%.

PV: Now, you’ve made it clear, now that we’re talking about Jomama, that it’s not a drag act. She’s another side of you that’s every bit as real as Daniel. Was it hard to make that switch the first time?

DAJ: Mm-hmm. For me it wasn’t because the way that she came through, and the first time she actually came through for me it was in 1995 so it was, I was working on my very first full length performance piece. She appeared in a way that was very different than a character that I created. I’ve written dozens of characters in different pieces and performed them, but that wasn’t what this was. So for me it felt more like a kind of channeling, being a vessel for this energy, which led me to number of different traditions. There are spiritual traditions where you’d become a vessel for an energy that is outside of who you are. There are traditions of performance, masked theater traditions in particular that I’m thinking about in in Asia and Africa where the mask, the external identity has a story, has information, has a particular set of characteristics and you as the performer actually surrender yourself to that energy. You take it on and it moves through you, it takes over your body, it moves your body in a particular way. Very often there are dances or songs that the mask knows that come through your body. And that is a valid and millennia old way of working.

The place that can be difficult I think is in how people view what I’m doing. It’s much easier to say it’s a drag act. It’s more complicated to talk about it in this way because it means opening up a different set of questions about what performance is and what identity is. I really don’t claim authorship of Jomama Jones, which is an odd thing to say as a playwright and a creator. I claim that I’m in a relationship with this energy and I create the circumstances. It’s kind of like building a melodic structure or a chord structure for a song, but the song when you play it live is always different every time.

In the jazz tradition, Betty Carter said one time something, she said, “It’s not about the melody, it’s about something else, the song.” So we often know a song by humming the melody. We’re like, oh, this is a song I know and I might hum, but the song is actually bigger than that. It has to do with the interpretation. It has to do with the way that the musicians approach it on that particular day and the epiphanies that lie between the notes. And that’s my work on Jomama, is I can give you a frame, but when I’m letting her through, she’s going to do what she’s going to do. And I’m not authoring that in a conscious way.

Now someone may come and say, “Well, that’s a subconscious thing. You’re still doing it. You’re still Daniel.” Fine. You can say that. But I choose very consciously to view it as part of I think a very ancient way of working. And I’m interested always in a more practical way, PV, in the idea that there are many people inside of us. Many aspects to us. And what happens if we give ourselves more freedom to think about identity as a multiplicity and a process rather than a static and fixed location? That interests me tremendously. And I think it might actually be a balm for some of the difficulties we go through in our culture that increasingly seems to need a static, flattened identity in order to assimilate and process.

PV: Wow, this is so much more deeper on a psychological level than I even imagined.

DAJ: You know that’s how I roll. That’s why these people, they run out of my class.

PV: Meanwhile, when you mentioned a mask, the first thing that came to my mind was the Jim Carrey movie, The Mask, where he literally puts on the mask and then becomes—

DAJ: In the mask itself.

PV: The mask takes over and he takes it off and goes, “Whoa. What was that all about?”

DAJ: What was that all about? Yeah. Which is a really, that’s a very funny pop culture version of this thing that is thousands of years old. Which is amazing to think about that, and what does that ancient wisdom tell us? Because there were so many different cultures throughout the world that masked play was integral to their religious traditions.

PV: Yeah. So you’re picking up on a very, very old tradition here. Speaking of old traditions, you’re turning 50 in February. Can I say that?

DAJ: Now why you going to try to put all my business in the street? You can say that.

PV: Hey, I’m an old man now. I just turned 45.

DAJ: All right. That’s good. Young.

PV: I’m not that far behind.

DAJ: I’m your elder. Respect me.

PV: I’m not that far behind.

DAJ: I love it.

PV: Yeah. So you’ve obviously seen a lot of changes in, when it comes to attitudes about gender expression in this country. And I wonder, do you feel like you’ve changed as well?

DAJ: I have. And I’ve been so inspired by… One of the places I really feel always that I learn from my students. I know that’s a kind of cliché thing that people say and they’re like, “Oh, I learn from them as much as they learn from me.” I’m like, I don’t know that that’s true. I think we have different ways of exchanging. But I’ve been heartened by their clarity. That they no longer wish to reiterate a very limited set of definitions about what identity is. And in regards to gender, that there’s just this steadfast refusal to accept this binary idea.

It’s been interesting because I’ve witnessed in my life the ways that a gender binary has been integral to keeping a lot of the oppressive systems that aren’t explicitly about gender in place. A lot of the power dynamics, a lot of the hierarchies that it slips in. And even if it’s not the thing that you see, if you dig, you’re going to find that binary at work. So I mentioned my book Waves that I’m working on, and I mentioned these mentors. And it is not lost on me that most all of the people who shaped me were feminists, womanist thinkers, particularly coming out of black feminisms. And black feminisms implicitly challenge ideas about flattened identity and challenge ideas about singular ways of being in the world, and a binary. They break all those things open. They demand that you think more rigorously and feel and be more rigorously.

So I’ve changed because I’m starting to experience things that I felt either only I was going through or a very small group of people were going through, I’m starting to see as being very much discussed in the public. So it’s been a very interesting experience to let go of a lot of that sense of isolation and say, “Oh, I’m not alone in my experience of gender,” which has always been a very fluid thing.

Now, I haven’t felt the need to define myself because I think I’m always a little bit suspicious of definition in general, but what I’m clear about is that I can look back at my work for 25 years, I can look back at my life for almost 50 years and say that this idea of ‘the many inside the one’ has always been true for me. That there’s a fluidity and there’s a curiosity in some ways. I think if I can make one other provocative statement that when we are with one another, we bring different things out of one another. Whether that’s a one-on-one conversation, like what we’re having right now, a classroom setting, a collaborative environment, making art, a city, a political party, a nation. We can go to any scale, but we bring different things out of each other. So I also think identity is not only about who you are within, but how you are without. How you are in configuration with other people. That you change in relationship, or different aspects of you are highlighted or suppressed in relationship to the people that you’re around.

PV: What’s next for Jomama?

DAJ: Well, I am currently working on the first stages of a brand new project that I’m building with the Public Theater and New York Live Arts as partners right now, and it is going to be a kind of ceremonial ritual performance project and I’m going to be working on it all year. In the spring we’ll be doing a sharing at New York Live Arts in early May of the first phase of this material, some portion of it. And Jomama is in it as a central figure, but there are a lot of other people who are involved. I just got done with this incredible workshop week with Josh Quat, who’s one of my musical collaborators, and then three extraordinary folks, Ebony Noelle Golden, Alexis Pauline Gums, and Shango Daria Wallace, who are all culture makers, leaders, activists. We came together this week and explored some of the first phases of the core questions of the show, and it blew my mind. So I’m buzzing with all this stuff and going to go sequester myself, rewrite my book, and write this new piece for the rest of the year.

PV: You’ve got a lot of work cut out for you.

DAJ: I do. I do. But thank you so much for chatting with me. I’m very happy to be part of your podcast.

PV: Thank you.

Bonus Track:

Patrick Verel: What does the term Afromystical mean, and why is it so important to understand you and Jomama?

Daniel Alexander Jones: One of the threads running through black American culture, and I would say you can make this observation of Afrodiasporic culture, period, is the relationship between cultural production and what you might call the divine or the numinous; the sense of the mystery of being and how close it is to our embodied everyday experience.

Zora Neale Hurston once talked about this principle called the juke, and the juke is like the juke joint. And we’ve all seen the juke joint in movies about the blues and you know, it’s the shack off in the woods or on the water where people go and they have their party, and they go and listen to the blues, and they get a little tipsy and they dance together. And what she says is in that space, an elevation will happen; that there’s something from the collective gathering and the movement with the music, and the collective energy of the people all dedicated to this kind of celebratory experience that will open up an experience of the life force that is larger than what you walk around with everyday.

And I think you can look at that and you can think about how that threads itself through black music. You can think about how it threads itself through dance, Alvin Ailey. You can think about how it threads itself through popular dance. You can think about how it threads itself through even the kinds of performative conversations and demonstrations and people’s own sense of beauty walking through the world. And then there’s a correlation in the black American sacred tradition in the church where people get the Holy ghost, right? Where you see the divine comes through. You may have seen it with gospel music that it lifts, and you get that shimmer; that vibration where all of a sudden, it feels like God is present, the divine is present, however you want to want to name that thing.

So, I’ve always been aware that what interests me is that meeting place between what we can never know; The universe, our ontology that is rooted in our sense of what cosmology is. That is the site where the work really, really happens. There’s a lift, there’s a change, there’s a transformation.

PV: Do you feel like you’ve been able to achieve that lift?

DAJ: I have. I have. And actually, Jomama has. Daniel does from time to time. But it’s part of the work, and it’s a long tradition. It’s not something I’m making up, but it’s something I participate in in my own way.

We had it recently when we did our show in Boston and there was this moment where the room, and it’s hard to describe if you’re not a performer, but there’s a kind of melting that happens that you can perceive if you will, when you’re presence of an audience. Performing live in the way that I do that involves some improvisation. Everybody in that room, you sense their energy, you sense their intelligence, you sense their perception. And you can feel almost like a circuit; what’s closed and what’s open, how the energy is moving through the room. And paying attention to it, there will be a moment if it does turn, there’s a moment where everybody knows that it turns, and all of a sudden, the circuit works in a different way.

And that thing, it happened, there was one particular show I can think of when we were in Boston that it happened, and I would say over half of the audience started to cry at the same time. It was phenomenal, and all of us who were making the show kind of looked at each other like, “Oh, it turned. The thing—” And it was dramatic because we didn’t expect that to happen quite in that way. But it said to me that there was a place where the individuals making up that audience, and then the collective experience of that audience connected with the subject matter of the piece which in this piece, had a lot to do with race and violence and conflict and the soul. And given what’s going on in the country, it’s like those things can be very hard to talk about in a public space. And there can be a resistance. And if that resistance flips, which is part of the technology of making a work, you know? It can be a tremendously liberating moment.

And again, what happens after when people leave the theater, I have no control over that as an artist, none whatsoever. But I can make an invitation to say to folks, what would happen if we sat with these ideas in these experiences together, and that we making the piece, will hold the room in such a way as not to leave you exposed in a way that’s cruel, in a way that tricks you. Because I think that’s a big part of it too. People don’t … Why would I show you something if you’re going to trick me?

PV: Right.

DAJ: And that’s not how I roll.

PV: Yeah.

]]>

Jones, an associate professor of performing arts who heads the playwriting curriculum in the Fordham Theatre program, was one of nearly 3,000 scholars, artists, and writers in the United States and Canada who applied for the fellowship, which has been overseen by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation for the past 94 years. Only 168 recipients were chosen.

The coveted awards, which vary in dollar amount by individual, are granted for use for six to 12 months, and carry no special conditions attached to them, allowing winners to spend funds in any manner they deem necessary to their work.

In a statement announcing his selection, the foundation noted that “energy” is Jones’ primary medium, drives his interdisciplinary practice, and supports his formal fluency and stylistic breadth. It praised his critically acclaimed performance pieces Black Light at the Public Theater and Greenwich House Theatre; Duat at Soho Rep; An Integrator’s Manual at La MaMa; and the Fusebox Festival, Radiate at Soho Rep, and Bright Now and Beyond at the Salvage Vanguard Theatre.

It also praised plays Jones has produced, such as Phoenix Fabrik, Bel Canto, Ambient Love Rites, and Earthbirths, Jazz and Raven’s Wings, as well as five albums of original songs he has composed as his alter ego, Jomama Jones.

“Daniel’s wildflower body of original work includes plays, performance pieces, recorded music, concerts, music theatre events, essays, and long-form improvisations. Jones consistently creates multi-dimensional experiences where bodies, minds, emotions, voices, and spirits conjoin, shimmer, and heal,” the foundation wrote.

“His roots reach deep into Black American and queer theatre and performance traditions. Jones is recognized as a key voice in the development of theatrical jazz and has made a significant contribution to black experimental theatre and performance.”

Since its establishment in 1925, the foundation has granted more than $360 million in fellowships to over 18,000 individuals, including Nobel laureates, Fields Medalists, poets laureate, and winners of the Pulitzer Prize, Turing Award, National Book Award, and other internationally recognized honors.

“Fordham’s theatre program is fortunate to have Daniel Alexander Jones on its faculty,” said director Matthew Maguire.

“Daniel sustains a high wire act of balancing a cutting-edge aesthetic with a deep well of compassion.”

]]>

Daniel Alexander Jones, who was honored as a Doris Duke Artist last year and was included in the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts’ top 100 artists this summer, has taken home yet another award: a USA Fellowship. The award, which is accompanied by an unrestricted $50,000 grant, recognizes America’s most accomplished and innovative artists.

“I have to knock on wood, because these things are quite rare. It’s an amazing thing to have my work recognized in this way, and for it to be in such a big fashion is totally humbling,” said Jones, who heads the playwriting curriculum in Fordham’s theatre program.

Jones received news of the win just as he was coming off another artistic triumph: the staging of Duat, an Off-Broadway play that the New York Times dubbed a “sui generis performance piece.”

With his current sabbatical ending in January, Jones is returning to the Lincoln Center campus, where he’s exited to teach his favorite course, Flying Solo, and start dreaming up and researching a new project.

“I’m really grateful to Fordham and my department in particular for supporting me as a working artist. It’s a difficult thing to balance teaching and have a career, but they understand how important it is to have working artists in our classrooms,” he said.

The USA Fellowship, which was created in 2006 by the Ford, Rockefeller, Rasmuson, and Prudential Foundations, honors disciplines as varied as architecture, folk art, and music, as well as theater. For Jones, the fact that the award is not tied to an individual project is particularly exciting, as it allows him to work on projects that don’t need to result in an immediate outcome.

He’ll need that time too, as the 2016 presidential election made it clear that there’s a greater need than ever for art that focuses on communication, building community, and inviting people to cross boundaries that appear to separate us, he said. This is the essence of Jones’ alter ego “Jomama Jones.”

For his next project, Jones plans to reach people who have never set foot inside a theater by putting on performances in nontraditional spaces. He said he’s guided by the truism, “Love and fear cannot exist in the same space at the same time.”

Fear of “the other” has been dominant these past 18 months, and whether that hate has manifested itself in racism, homophobia or xenophobia, Jones said he is hopeful that theater has a place in fighting it.

“One of the things that I think live art—and theater in particular—can do is to help us see one another, and to see ourselves,” he said.

“When you can really see somebody in all their complexity, and you feel seen in all of your complexity, it’s a little bit harder to move on feelings of fear.”

]]>His 2016 fellow honorees include Harry Belafonte, Stephen Curry, Humans of New York, Beyoncé Knowles and John Legend.

Jones, who heads the playwriting curriculum in the Fordham theatre program, said he was elated to be included on the list, which he called breathtaking.

“What I love about this list is that it’s artists, social activists, entrepreneurs, and critical thinkers and writers who are from a variety of different traditions and who are all engaged in using arts for social change,” he said.