“I hope that we can continue to make memories and find ways to come together,” she says of the affinity chapter, “because I think Ailey and Fordham have such a special history. It’s an incredible program.”

Where did you grow up and how did you end up in the Ailey/Fordham program?

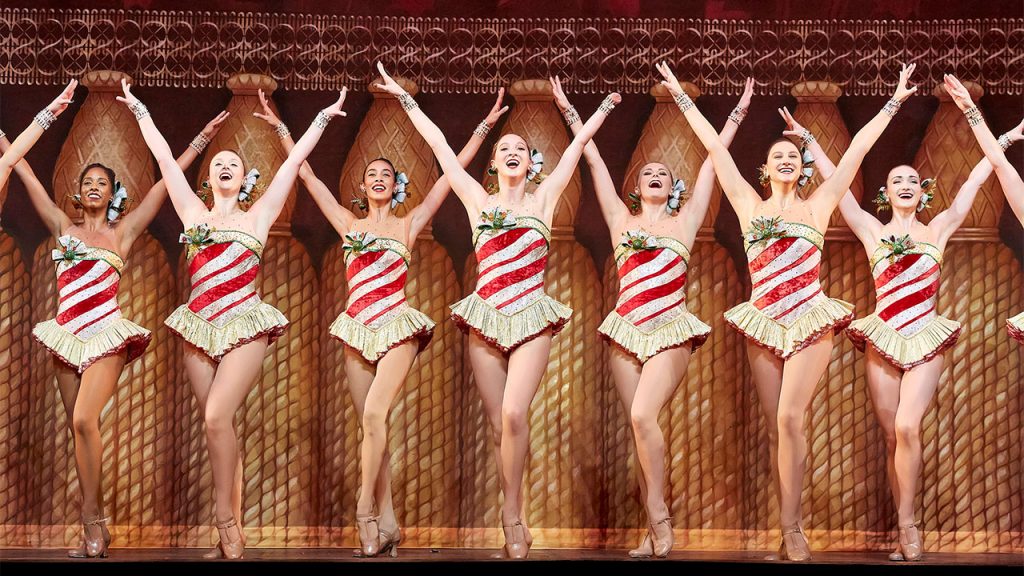

I grew up in Mesa, Arizona. The summer after my junior year of high school, I actually attended the Ailey Summer Intensive and got to stay in the dorms [at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus] for six weeks. That was a little sneak peek of what college could look like for me. My four years at Fordham were absolutely amazing. I definitely wouldn’t be where I am today without the Ailey/Fordham BFA program. I actually saw the Christmas Spectacular for the first time my freshman year of college through tickets that I got from Fordham.

And did you get to do any workshops with the Rockettes at Ailey?

Yes, they would come in and do workshops at Ailey about two or three times a semester. The spring of my sophomore year, I auditioned for the ensemble in the Christmas Spectacular, and I did that the fall of my junior year. So I was working and going to school and was a part of the show. Then, after I graduated, I auditioned for both the ensemble and the Rockettes. I would’ve been ecstatic either way, but I was offered the role of Rockettes for the Christmas season in 2021, and I’ve been doing it ever since.

So when do rehearsals start for the Christmas Spectacular?

They usually start at the end of September or early October. And we rehearse for about six weeks leading up to opening night, six days a week for about six hours each day. And we slowly layer on choreography, tech, with lighting, costumes, the orchestra, and then it’s opening night and we’re doing it every day up to four times a day. Typically, we do up to 15 or 16 shows in a week.

What are you doing for the rest of the year?

All of us are doing different things, but for me personally, I teach dance and I’m a fitness instructor. I also still do a lot of things with the Rockettes in the offseason. I’ve actually been able to go back to Ailey and teach classes, both at Ailey and at Radio City, where we actually bring the dancers to the music hall and give them that experience of rehearsing there. That has been really special because that’s how I got my introduction to the Rockettes, those workshop classes.

Outside of that, we always keep up with social media and doing different routines and additional performances that pop up last-minute. But then all of a sudden, it’s Christmastime and we’re back at the hall rehearsing and performing for 6,000 people every night. So it goes by quickly. Really, we’re always working and doing things in that time to prepare for the next season.

How do you manage seeing family and friends around the holidays?

I’m so fortunate that my family and friends make their way out here for the holidays. My parents were actually just here for a few performances, and they may come back up for Christmas. But they know that this show is where I’m at during the holiday season, and they’re just so proud of me. And I think that’s what’s special—I can make new memories during the holiday season, and I’m glad that I’m able to make the time to FaceTime and call and send gifts or do whatever it may be to stay connected.

What would your childhood self think about your job?

I think little Maya would be in awe of where I’m at now and would probably not even believe that that’s how I’m spending my Christmas morning. It’s definitely a huge dream come true that I didn’t even know was a dream at the time.

What’s your favorite part of the show?

I really do love our “New York at Christmas” number. We’re on a double-decker tour bus, which takes us through New York City and Central Park and Fifth Avenue, and then you end up at Radio City Music Hall. I love how it incorporates everyone in the show—the singers, the ensemble, the principals. And there’s moments where I’m on the bus and you can really look out into the audience and see individual faces of some of those kids, and their eyes really do light up when they see us come on stage. I feel like it’s one of those numbers that you take it in, like, “Wow, I’m performing at Radio City Music Hall.”

What’s your favorite Christmas song?

“Jingle Bells.”

What’s the best gift you’ve received?

I’m a sentimental person, so just a classic Christmas card from friends or family. I usually keep all of those.

What’s your favorite place in New York City at Christmastime (that’s not Radio City)?

This might be a boring answer, but my apartment. I feel like after the shows and the busyness of the holiday season, I think being at my apartment—which is very much decorated with the holiday spirit and it’s just super cozy—is my favorite place at the end of the long day.

—Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Adam Kaufman, FCLC ’08.

Check out more photos from the Radio City Christmas Spectacular below (all photos courtesy of MSG Entertainment).

RELATED STORY: How to Become a Radio City Rockette

RELATED STORY: Inside a Dream Internship with the Radio City Rockettes

]]>

They step in unison, arms pumping down in front of them like pistons. They kick a leg out and, exactly on the six-count, spin 90 degrees to repeat their march. Then again, another 90 degrees, before launching off the ground for a spin. Floor-to-ceiling windows frame their movements with views of West 55th Street and Ninth Avenue, where cars, buses, and pedestrians are engaged in their own choreography, sometimes slowing to take in the studio scene. There’s no music inside—only footsteps, hard breathing, and shouted notes of correction and encouragement.

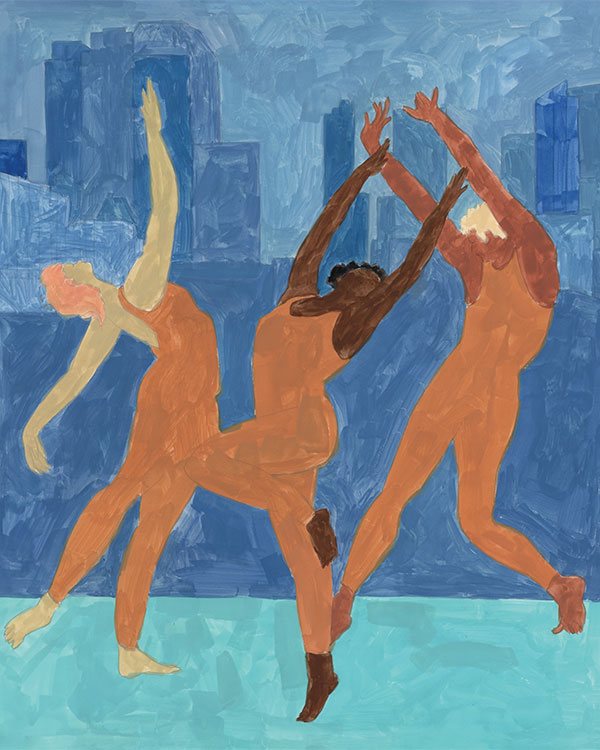

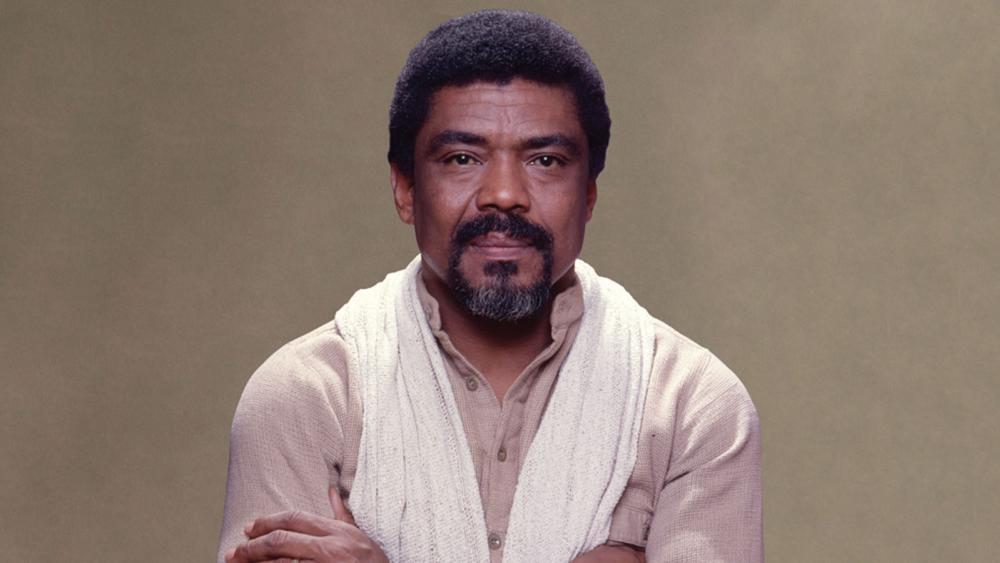

The dancers are seniors in the Ailey/Fordham BFA in Dance program, which is celebrating its 25th year. They’re in the Joan Weill Center for Dance in Manhattan—home of the Ailey School, five blocks from Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus—rehearsing teacher and choreographer Earl Mosley’s Running Spirits (Revival and Restaging) for the program’s annual benefit concert in mid-April.

In another ground-floor studio about a month before the concert, first-year students take West African Dance with Imani Faye. As a drummer slaps out a beat on a djembe, Faye guides the students through their own performance piece, Den-Kouly (Celebration), with its traditional Tiriba and Mané dance styles from Guinea.

As the students work to nail the choreography, they’re also grappling with bigger, more complex movements. For the first-years, it’s the culmination of nine months spent testing themselves, body and mind. Are they able to balance a rigorous dance training program and a rigorous academic curriculum? And for the seniors, it’s a time of final exams and frequent auditions. Are they ready to secure their place in the professional dance world?

Carrying on the Legacy of an American Dance Pioneer

The idea for a best-of-both worlds BFA program—top dance training and top academics in New York City—came several years before the first class arrived in the fall of 1998. Edward Bristow, then dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center, struck up a conversation with Ailey School director Denise Jefferson in line at the West 60th Street post office. He believed Fordham could do more to make its presence felt “at the center of the arts world,” and Jefferson was interested in building a college degree program for Ailey dancers. “We knew that given our strengths, we could pull off something special,” he recalled.

Today, the program is led by Melanie Person, co-director of the Ailey School, and Andrew Clark, a Fordham professor of French and comparative literature who had served as an advisor to many BFA students before succeeding Bristow as co-director in 2023. Through their leadership, the Ailey/Fordham students are staying true to the vision set forth by Bristow and Jefferson, who died in 2010. They’re also upholding the legacy of Alvin Ailey himself, a towering figure in modern dance.

Ailey founded his namesake dance company in 1958, when he was 27 years old. His story and the story of the company he founded are inextricable from the histories of Black art in America and the Civil Rights Movement. At a time when Black dancers found it next to impossible to make a career through their craft, Ailey created a home for them. Since its inception, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater has become not only one of the most successful Black-founded arts institutions in the United States but also one of the premier modern dance companies in the world, described in a 2008 congressional resolution as “a vital American cultural ambassador to the world.”

Texas native Antuan Byers, FCLC ’17, is one of many BFA students and alumni who say they were drawn to the program after seeing the company perform during their formative years. “I attended my first Alvin Ailey performance my senior year of high school, in that moment of still being on the fence about where I wanted to go to school,” said Byers, who was a member of Ailey II, the company’s junior ensemble, and now dances most frequently with the Metropolitan Opera. “After seeing the Ailey company, it all became clear.”

For many Black students in the BFA program, Alvin Ailey’s legacy serves both as an inspiration and a reminder of the challenges that dancers of color have faced. It’s hard to miss that legacy when you’re inside the Weill Center, with its walls lined with photos and ephemera spanning seven decades.

“Every day I try to use the weight of his legacy to further encourage me and push me in my craft,” said Naia Neal, a rising senior from Santa Cruz, California, who earned the program’s Denise Jefferson Memorial Scholarship and is pursuing a minor in math. “Alvin Ailey loved to dance, but he also understood that dance should be for everyone. He made it known that everybody deserved to be there.”

The dance landscape looks a good deal different today than it did in 1958. Black choreographers like Kyle Abraham and Camille Brown have had their work performed by New York City Ballet and the Metropolitan Opera; Black dancers are members of most major companies in the United States; and Black administrators are artistic directors at places like Pacific Northwest Ballet and Philadanco. But on many stages, Black dancers are still underrepresented, and for many students of color, a place like the Ailey School still functions as a home where they can chart a professional path.

“Something about being here has opened up a completely different relationship with me and what I add to different spaces and what it means to be a Black dancer,” said Carley Brooks, a rising Ailey/Fordham senior from Chicago pursuing a minor in communication and media studies. “The [Ailey] building allows me to feel so comfortable and confident in my body and what I have to present.”

Developing the Whole Dancer

If one thing defines the Ailey/Fordham experience, it’s the need to find balance within a hectic schedule. All students take ballet every semester, a way to keep them grounded in classical technique, and in their first year, they also take West African Dance and begin training in either the Horton technique or Graham-based modern dance. They also have foundational classes like Improvisation, Body Conditioning, and Anatomy and Kinesiology. And they take two Fordham core curriculum classes each semester, including first-year staples like English Composition and Rhetoric and Faith and Critical Reasoning.

In their sophomore year, students decide if they want to pursue a second major or a minor. It’s a decision they don’t make lightly, as it comes with extra coursework, but for many students, it’s a way to help them plan for careers beyond performing—and to infuse their dance practice with outside influences. That year, they also take Composition, and for many of them, it’s the first time they formally work on their own choreography—a complex process, with varying notation systems and a good deal of trial and error.

As juniors, the students continue to branch out intellectually. In the Ailey academic class Black Traditions in Modern Dance, they engage with history while also thinking about the artistic choices involved in a performance. Meanwhile, in Fordham classrooms, many begin fulfilling the requirements for a second major.

They also have a chance to become mentors to their first-year counterparts. Jaron Givens, a rising senior originally from Prince George’s County, Maryland, who is majoring in both dance and environmental studies, has relished the opportunity to pay forward the mentorship he received during his first year. He took part in the Ailey Students Ailey Professionals mentorship program, which pairs students with Ailey company members. Givens met with Courtney Celeste Spears, FCLC ’16, who he said “facilitated a space where I was able to be vulnerable … and showed me how much Ailey cared.”

The Ailey School has been working with Minding the Gap, an organization that offers mental health services to dancers. The hope is to give students as much access to mental health support as they have to things like on-site physical therapists at the Weill Center. On the Fordham side, faculty describe a similar focus on students’ well-being. “I try to … get a sense of what their concerns are, what they’re enjoying, and what they’re struggling with,” Clark said. “That’s where you really get a sense of the whole person and you have the ability to help out.”

There’s also a natural level of camaraderie that comes from spending so much time with fellow BFA students, both in dance classes and often in academic ones. “For us, it’s not a competition,” said Sarah Hladky, a rising junior who is majoring in English as well as dance. “Ailey very much emphasizes the fact that there is a space for everyone. And so even if people come in feeling like they need to prove themselves, at the end of the day you leave being like, ‘No, I am the dancer that I am, and you are the dancer that you are. And we can coexist and really make a great environment for each other.’”

While a sense of community is integral to the Ailey/Fordham experience, students are well aware that they’re training for a highly competitive profession. The postgrad goal for many of them is to join a dance company full time—with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and Ailey II often at the top of the list. Many alumni earn a spot in those companies and others such as Dance Theatre of Harlem, the Martha Graham Dance Company, and the Radio City Rockettes. Others regularly appear on Broadway stages and in film and TV productions. But a benefit of their Fordham studies is that they graduate prepared for any number of career paths.

“My education at Fordham was instrumental in my formation as an artist and businesswoman, providing me with a depth of knowledge, curiosity, and appreciation for many subjects that gave me a foundation to build on,” said Katherine Horrigan, a 2002 graduate who went on to dance with Ailey II, Elisa Monte Dance Company, and a number of other companies around the world before launching a dance academy in Virginia.

Spears encourages Ailey/Fordham students to “build your academic resume as much as you build your dance resume.” She said the program expanded her ideas of what she could do as an artist and a leader. She began dancing with Ailey II in 2015, her senior year, and moved up to the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater before deciding in 2023 to focus full time on ArtSea, her arts organization in the Bahamas. “I think if you focus on having viable options and stretching how many different places you are able to impact, you then have the mountaintop,” she said.

[RELATED STORY: “Bridging Art and Entrepreneurship”]

For Samar Haddad King, a 2005 Ailey/Fordham graduate, a composition class with Kazuko Hirabayashi was so transformative that she decided to focus on choreography. For her class’s senior concert, she premiered an original piece, and the following year, with her BFA classmate Zoe Rabinowitz, she co-founded the company Yaa Samar! Dance Theatre, based in both New York City and the West Bank. Nearly 20 years later, they have brought their work to 17 countries around the world.

Rabinowitz has carved out her own unique path since graduating in 2005. While she still dances in Yaa Samar! and elsewhere, her role as the company’s executive director builds upon several post-college jobs in arts administration, and she has also taught yoga and Pilates throughout her career. Acknowledging the finite amount of time most people can dance professionally, she said it’s important for young dancers not only to develop academic interests but also to take an expansive view of the dance world.

“Finding the things that you enjoy doing—the passions and the strengths that you have cultivated inside and outside of your dance training—and finding ways that you can do those things to implement jobs and create sources of income is going to be critical for most people,” Rabinowitz said, adding that dancers are known as great team members across industries. “Recognize that you come with a really strong skill set and work ethic, and that you have the capacity to do a lot of things.”

Person, the Ailey School co-director, echoed that sentiment. “The skills that they acquire as dancers are going to be transferable in any aspect of their lives. With the Fordham degree and their strong academics, they’re well situated to exist in the world.”

Whatever part of the dance or professional world they end up in, Ailey/Fordham alumni often maintain the close bonds they shared as undergraduates, and now there’s an additional way for them to stay connected. Ahead of the program’s 25th anniversary, Byers and Maya Addie, a 2021 graduate who is a member of the Radio City Rockettes, learned about Fordham’s affinity chapters—alumni communities formed around shared interests, past student involvement, or professional goals. They decided to start one for Ailey/Fordham BFA graduates.

“It’s a personal goal of ours to bring together our alumni because we have such a wealth of knowledge in that group,” Byers said. “In dance but also in our incredible business owners, or folks working in politics, folks working in finance, people teaching, people with kids. We see this 25th anniversary as an opportunity for us to really build an alumni program with all that excitement and energy.”

A Performance to Mark Endings and New Beginnings

On the evening of the spring benefit concert, after a cocktail reception on the sixth floor of the Weill Center, family, friends, and fans of the BFA program made their way to the Ailey Citigroup Theater on the building’s lower level. Following a brief video highlighting the history and mission of the program, Neal kicked off the evening’s performances with The Serpent, a solo piece choreographed by Jonathan Lee. To the pulsing beat of Rihanna’s “Where Have You Been,” she gave a high-energy performance that incorporated styles ranging from modern and hip-hop to voguing. Unlike the more restrained audience traditions one might see up the street at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, the audience cheered throughout the piece.

That energy level, both onstage and in the crowd, continued with the first-year students’ West African piece, Den-Kouly (Celebration), featuring vibrant costumes and jubilant movement. The sophomores performed an excerpt from the more ballet-centric For They Are Rivers, choreographed by Becky Brown, and the juniors danced an excerpt from Darshan Singh Bhuller’s athletic, abstract Mapping. Three Ailey/Fordham alumni—Mikaela Brandon, FCLC ’19; Naya Hutchinson, FCLC ’21; and Shaina McGregor, FCLC ’18—came back to dance alongside Neal in Four Women, choreographed by senior student Baili Goer.

The final performance of the night, appropriately, belonged to the seniors. Since that March rehearsal of Running Spirits, Mosley had revealed to the students the meaning behind the piece, which he first choreographed for a group of preteen boys at a summer program in Connecticut in the late 1990s. At the time, he explained, he was dealing with a group of rambunctious kids who loved to run around—and whose parents thought of them as “little angels.” It made him imagine a scene in which a group of angels, who get around via running instead of flying, are all gathering in the morning to plan out their work agenda for the day.

“When I tell dancers that’s what it’s about,” Mosley said, “they always laugh because they’re like, ‘Really? That’s all? So we’re just literally getting ready to go to work?’ I’m like, ‘Yeah, you’re just getting ready to go to work.’”

It’s a playful piece, but the version Mosley created for these graduating dancers is one that requires strong technique and collaboration, and features impressive jumps, lifts, and, as the title suggests, speed. There was a sense of mischief onstage, an almost conspiratorial glee to the movements. That tone felt appropriate considering all the students had been through in their nearly four years together, from beginning the program at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic to trying to wrap up their final semesters while planning for the future.

“This past year has probably been the most challenging in terms of juggling my schedule,” said Meredith Brown, a dance and economics double major from Asheville, North Carolina. “Because I’m also auditioning and making sure that I’m taking care of myself and enjoying the city and taking advantage of all these wonderful things.”

Brown and her fellow 2024 graduates are in a better place to manage those competing demands than they were four years ago—not only more experienced but also more confident.

“When I think about my first year, there was a lot of imposter syndrome,” said Abby Nguyen, a 2024 grad from the Bay Area who double majored in dance and psychology. “There was this constant feeling like I needed to prove myself, that I needed to prove that I was good enough to be here. But ultimately, you are here, and you are good enough to be here—or else you wouldn’t be in the building.”

The dancers’ growth has also been visible to Person, who recalled the challenges the Class of 2024 faced starting college during the pandemic. “I was watching them rehearse the other day, and I think they really came together as a class,” she said. “I think they relied on each other to push through this, honestly. … I think it gave them this inner strength that they might not have even recognized that they have.”

And while challenges certainly lie ahead—auditions, demanding dance jobs, the threat of injuries, and more—Mosley believes this group of graduates is ready to face them.

“They give me the energy like, ‘Oh, I know I’m going to do something,’” he said. “‘There’s

no doubt, I’m going to do something.’ This group as a whole is all about it.”

“Jonathon was a caring and compassionate educator who had the kind of multilayered career that one can only marvel at,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, in an email to the University community. “He was thoughtful and creative, with a talent for drawing connections among disciplines.”

Appels taught in Fordham’s English, African and African American studies, anthropology, dance, history, communication and media studies, Middle East studies, theology, and visual arts departments, as well as the religious studies, comparative literature, and urban studies programs, from 1996 to 2002 and 2009 to 2021. He offered a colorful mix of courses, including “Madness and Literature” and “LGBT Arts and Spirituality: Mystics and Creators,” mostly at the Lincoln Center campus.

“His mind was eclectic and his education and curiosity was unmatched,” said Anne Fernald, Ph.D., professor of English and women, gender, and sexuality studies. “Endlessly curious, he always had a new story of the latest lecture or performance he had attended. He was a wonderful storyteller, with a rich laugh. He took me out to a vegan restaurant once, hoping to encourage me in more healthy habits. He was always cold and wandered the halls draped in wonderful scarves.”

Appels was a scholar, poet, musician, sculptor, and art critic who conducted research in 20 countries, largely in Europe; he was also a member of nine humanities associations.

“He had a very probing mind, and he was very good at connecting the dots between various disciplines and departments,” said his husband, David LaMarche. “He was a very animated and inquisitive person with strong opinions, but not rigid … a free spirit and sort of counterculture, since the time that we were born in, the early sixties, and a sensitive man who loved every branch of the arts.”

His First Love

But what most academics weren’t aware of, said his husband, was his love for dance.

“He loved teaching, but his first love was probably choreography,” LaMarche said.

Appels was a dancer and choreographer who founded his own dance company, Company Appels, in 1979. He performed across the country and the world, from the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City to international stages in France, Germany, and Portugal. He choreographed modern dances for scores of performers, principally graduates of the Juilliard School, SUNY Purchase, and North Carolina School of the Arts. One of his favorite courses he taught at Fordham was part of the Ailey/Fordham BFA Program in Dance, run jointly with the Ailey School, said his husband. Even off stage at more casual venues, you could find him dancing.

“He loved disco dancing and he loved to dance, even into his sixties. If we ever went to a gala party or something like that, he’d always be on the dance floor, wild,” said LaMarche, a pianist who first met Appels at a dance class in San Francisco.

Appels’ passion for the arts was recognized worldwide. In 1998, he was awarded a Fulbright to teach modern dance at the National Dance Academy in Hungary. (He received another Fulbright to study the archives of a famous philosopher in Belgium in 1991.) In addition, he received an artist fellowship from the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts and a William Como Award from the New York Foundation for the Arts.

In a 2014 reflection, a Fordham alumnus praised Appels for showing him the beauty of dancing through his course called Lincoln Center Arts.

“I never considered dance to be very interesting, running the other way when friends would suggest going to the ballet … I now found myself discussing Balanchine, Paul Taylor, and Dance Theater of Harlem with anyone who would listen,” wrote Jason McDonald, who took the course as a Ph.D. student.

‘Now Keep That Big Smile’

Appels was a thoughtful instructor who wanted his students to take away something meaningful from his classes, said Thomas O’Donnell, Ph.D., co-chair of Fordham’s comparative literature program and associate professor of English and medieval studies.

“Jon really wanted his students to become exposed to very different ideas. He was a very curious and open-minded person, and it seemed that his lessons as a result were full of that same spirit,” O’Donnell said. “He cared about his students very deeply. For every student that I would talk to him about, he had some story or insight about their biography and who they were. He really wanted to get to know the students so he could help them better.”

He loved speaking with students about their work over the phone, said LaMarche. Before their calls ended, he left them with a unique message.

“He ended almost every phone call with a student by saying, ‘Now keep that big smile,’ which I thought was so cute,” LaMarche said, chuckling. “You can’t see someone smile over the phone, but he would always say that to them.”

An ‘Off-the-Grid Educational Experience’

Appels was born on May 17, 1954, in Falfurrias, Texas. His father, Robert C. Robinson, was a sales executive for oil companies and a financial planner; his mother, Patricia Robinson, neé Hosley, was an elementary school teacher. When he was a child, his family frequently moved because of the nature of his father’s job, said LaMarche. He lived in Nigeria and Libya and later settled in California.

“He was exposed to a lot of different cultures as a youngster … He got his B.A. at Western Washington University at a college called Fairhaven College, which was a very experimental educational institution at that time,” said LaMarche. “That started his off-the grid educational experience.”

Appels earned a bachelor’s degree in art and society from Western Washington University, a master’s degree in music from Mills College, a master’s degree in poetry from Antioch University, and a Ph.D. in comparative literature from the City University of New York.

Outside of Fordham, he taught undergraduate and graduate students at Columbia University, Cornell University, Princeton University, Rutgers University, and his alma mater Western Washington University. He enjoyed yoga, pilates, gyrotonics, acupuncture, and other forms of Eastern medicine and healing. Instead of ironing his shirts and wearing a suit jacket like many professors, he preferred a loose and casual style, LaMarche said. He was a spiritual man who loved nature, especially walks through the woods and summers spent with LaMarche in Ithaca, where they swam in waterfalls, gorges, and lakes. He disliked technology, especially computers—in fact, he never owned one, said LaMarche, who managed his husband’s online accounts.

In addition to LaMarche, Appels is survived by his father, Robert; brother, Robert H. Robinson and his partner, Ilona Robinson; and his sister, Carol House, her husband Roger House, and their son Josiah. A memorial service will be held for Appels sometime early next year, said LaMarche.

]]>That is how choreographer Jeremy McQueen, FCLC ’08, a graduate of the Ailey/Fordham BFA in Dance program, describes his response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

As the artistic director and choreographer of the Black Iris Project, the collaborative dance company he founded in 2016, McQueen experienced the kind of upended plans so many in the arts have dealt with since last spring. He had been scheduled to begin a two-week residency choreographing for Nashville Ballet last May when the pandemic forced the company to cancel the rest of its season.

After the loss of that gig and the postponement of several planned Black Iris Project pieces, McQueen focused on a work he had been considering for some time: a ballet film about New York City youth in the juvenile justice system, taking inspiration from Maurice Sendak’s 1962 Caldecott Medal-winning children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are.

McQueen is releasing the film, WILD, in four parts. After premiering on BronxNet television on March 13, the second part, WILD: Act 1, is available for streaming rental until April 11. The first part, WILD: Overture, aired in November.

Taking Risks and Amplifying Voices

As a director and choreographer, McQueen took inspiration not only from Sendak’s book but also from a photograph by Richard Ross that he saw at the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama. The photo serves as the cover of Ross’ book Juvenile-in-Justice, part of a multimedia project examining the harsh conditions faced by youth placed in the juvenile justice system.

WILD: Act 1 follows a boy, played by Ailey II member Elijah Lancaster, as he seeks to mentally escape from the claustrophobic room he has been placed in at a juvenile detention facility on his 14th birthday. Through movement, along with music, illustrations, video projection, and audio recordings of interviews, the piece explores the effects of isolation and trauma on the young people who are held in confinement.

“I think this is probably one of the most striking works that I’ve created to date,” says McQueen, whose previous filmed ballet, A Mother’s Rite, was nominated for a New York Emmy Award in 2020. “It’s definitely one where I’ve taken greater risks than I’ve ever thought I could take.”

Part of that risk, according to McQueen, involves wanting to make sure he is properly telling the stories of a group of young people whose voices often go unheard. While he says that he has received positive feedback from practitioners in the juvenile justice field—as well as attention from The New York Times—he is staying attentive to the subjects of the work.

“One of the biggest things that keeps me up at night is wanting to make these young people proud,” he says. “It’s less about the accolades or what can come from it, but I’m constantly focused on how I am able to hopefully adequately amplify the voices of these young people.”

Catharsis and Collaboration

While the pandemic prevented McQueen from filming the piece in a juvenile detention center, which was his original goal, he was able to find creative ways to stage the piece safely. He and his dancers rehearsed the piece both on Zoom and in person during a two-week “bubble” residency at Vineyard Arts Project in Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, and it was shot without an audience by cinematographer and editor Colton Williams in the black box theater at the 14th Street Y in New York City.

According to McQueen, completing the project was never in question.

“You have to figure out a way to do this, because if you don’t, you’re just going to vanish,” he says he told himself. “You have to continue to have a presence in some kind of way, and to shift your mission to still connect with community, even if that means connecting with them virtually.

“Art has always been so healing for me,” he added. “It was important to me that I continue to let my art heal me in the sense that this project has been incredibly cathartic for me, but also for other artists that [were]so needing of work and opportunities to creatively stay inspired and stay engaged.”

Along with Williams, the dancers, and a number of visual artists who contributed to the piece, McQueen collaborated with several musicians who provided both commissioned and existing songs to the piece’s mixtape-style soundtrack, including the singer-songwriter Morgxn, whom McQueen had originally been paired with for the residency at Nashville Ballet; former Hamilton cast member Phillip Johnson-Richardson, who goes by the moniker Phil.; and R&B artist Brittany Campbell.

McQueen says that he has learned a lot about directing by diving into the work and experimenting, an approach for which he credits Ava DuVernay, director of films including Selma and 13th, as an inspiration.

“The best way to learn is just to start, and that’s one thing that I’ve really held close to my heart from her teachings,” he says. “Don’t worry about not having the degrees or the credentials, just start playing. A lot of these things I’ve learned how to do out of necessity—figuring out how can I do this and what creativity can I bring to the table to truly diversify the industry in such a crowded dance market.”

‘Bringing All of Myself’

McQueen’s plans for the remaining two parts of WILD speak to his ambition and creativity. For the third part, Entr’acte, he is staging a socially distanced bike excursion throughout the Bronx, where audience members will travel to five locations. At each one, a dancer will tell the story of a young person from the borough who has been impacted by the criminal justice system. And in the fall, he will premiere the final part, Act 2. McQueen says that when he is able to tour the piece, he plans to stage the Entr’acte bike excursion prior to the stage performance in each tour city.

And once all parts have aired, McQueen has even bigger plans for WILD.

“Our goal is Netflix or HBO or Amazon Prime, some sort of worldwide streaming platform,” he says. “That’s one of our goals for this package of WILD with all four parts: being able to see and experience dance on those platforms in ways that we haven’t been able to do. There are TV shows about dance. There are dance documentaries. But there’s not really a dance film of this caliber or nature yet, and we’re hoping to be one of the first to do that.”

Regardless of where WILD takes him, McQueen makes it clear that he will continue to tell the stories he feels are important, even if they have not traditionally been given exposure on ballet stages.

“One of the things that I have to stand very firmly about is being able to bring all of myself,” he says of how he will choose future projects and collaborations. “I feel like in the past, only parts of my Blackness, only parts of my being, were accepted or allowed to be brought into the room.

“I understand that you have to understand your audience, but I also think that it’s important to push boundaries. That’s the only way we can really grow as individuals and as an artistic [community], is to strip away the veil and talk about what’s really happening in our country.”

]]>Junior Joslin Vezeau, the recipient of the Denise Jefferson Memorial Scholarship, performed a solo dance to Mercer’s “All in Love Is Fair,” while group numbers were performed by the freshman, sophomore, junior and senior classes, respectively. Whether poised onstage or posed mid-air, students brought line, shape, and spirit to the language of movement, creating dramatic renderings of each choreographer’s vision.

[doptg id=”80″]

]]>For their annual benefit concert, students performed a series of new pieces from renown choreographers, such as Nicholas Villeneuve (“The Soul’s Canvas”), Natalie Lomonte (“Common Heart”), and Andre Tyson (“Raison d’etre”). The concert, held at the Ailey Citigroup Theater in Manhattan, attracted more than 100 guests.

Whether dancing solo, creating a unified expression, or building the illusion of two-bodies-as-one, each dancer’s personal element of feeling helped create moving metaphors of the choreographers’ poetic visions. As always, the theater audience recognized the 75 student dancers with enthusiastic applause.

[doptg id=”47″](Photos by Christopher Duggan)

In a behind-the-scenes video of a new commercial by Intel, Fraser shares the story of how she overcame her physical struggles and became a professional dancer. After graduating from the Ailey/Fordham BFA in dance program, Fraser spent two years dancing around the world with Ailey II, the highly selective junior company of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. She is a founding member of Visceral Dance Chicago and is currently in her third season with the company.

Watch Fraser’s story below.

]]>

Thursday, March 10, 2011 | 7 p.m. (5:45 p.m. pre–performance cocktail reception)

Pope Auditorium | Lowenstein Center | Lincoln Center Campus

In the last 12 years of her life, Denise dedicated much of her energy to the development of dancers in the Ailey/Fordham BFA Program in Dance. The University will remember and celebrate Jefferson in this performance. The proceeds will make it possible for Denise Jefferson’s’s dreams to continue in the training of exceptionally gifted dancers in the Ailey/Fordham program.

Ailey/Fordham B.F.A. Benefit Committee

William F. Baker, Ph.D.

Clifton Brown

Elizabeth Burns, FCLC ’83

Andrew H. Clark, Ph.D.

Patricia Dugan, FCLC ’79

Amanda Hearst, FCLC ’08

Tickets required. Register Online

For event information, please contact Jill Logan at (212) 636-6440.

To support the Ailey/Fordham BFA program, please contact Rodger Van Allen at (212) 636-6562 or [email protected].

]]>