“We hope to create a platform that will allow scholars and the general public to access data across museums through a simple and visually appealing online interface,” said Laura Auricchio, Ph.D., dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center, a co-principal investigator for the project.

Several representatives from major museums and libraries, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Library of Congress, were present at an October project workshop at Fordham. Joining them were scholars from Fordham, Harvard University, MIT, the New School, Sciences Po of Paris, and University of Potsdam in Germany. The group has been collaborating continually to produce a final report for the NEH in March, after which they’ll seek additional funding for the project.

Connecting Museums and Their Data

Auricchio said that the project is similar to how museums are connected in the physical realm through the exchange of traveling works of art, but instead of art they would be exchanging research data, or metadata, spawned by their collections. Auricchio distinguished the two data sets by using museum “tombstones” as an example. Tombstones are the placards one sees beside a painting in a museum. The metadata would be the boldfaced information found at the top of the placard: the name of the artists, the years the artist lived, the name of the work of art, and the medium. The research data would be the paragraph below the metadata, which would include more nuanced and detailed information about the painting: its history, influences, and place within art history. Also included in the research data would be essays from exhibition catalogs.

“Only a fraction of a museum’s holdings are photographed for catalogs, the rest is represented through this research data and metadata,” she said.

This new platform would help foster “a new kind of knowledge production for scholars, artists, curators, educators, and an interested public,” she said.

Anne Luther, Ph.D., a co-principal investigator on the project, said that one of the primary challenges is that museums publish their data in silos, and even within institutions the internal databases don’t necessarily follow the same protocol. Luther, along with Auricchio, brought the NEH-funded project to Fordham.

“A museum may have one database system they are using, but from department to department they are using it differently,” Luther said at the October workshop. “The goal is to make this data available as a public good, but at the moment they’re [the data] not speaking to each other.”

The challenge in dealing with large institutions is that the computer science protocols have already been established, in many cases over the course of years. Luther said there have been long-standing efforts that try to connect museum data internationally, but projects that have tried to impose new standards and new protocols have failed.

“We’re not trying to bring new standards to describing metadata, but rather we want to build, on one side, a protocol that would allow us to connect them,” she said. “We want to allow for the diversity of metadata on object descriptions within the museums to remain the same. We’re not asking the museum to rewrite. We’ll fish that out.”

Speaking the Same Language

Of course, “fishing” for common phases that describe a period, or a work of art, is also one of the great challenges for the project.

Sarah Schwettmann, a graduate student at Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines, said a protocol layer that aligns metadata from museums’ digital collections could be the best route. She noted that with machine learning, which is akin to artificial intelligence, there are increasingly more tools that allow computer scientists to work with and analyze metadata. She said the resulting platform needn’t be a simple search engine or website, but could be something more.

“We could build a protocol that actually asks, ‘Can we compare how different museums talk about items in their collection?’” Schwettmann said at the workshop. “This interface would allow one to interoperate specific terms and cultural language that the various museums have developed over time. This is important because each museum develops bodies of scholarship that are specific to that institution.”

“We want a protocol layer that points back to how individual museums talk about their objects and allows users to interact with and see the diversity in terminology,” she said.

One-Stop Research

Matthew Battles, associate director, metaLAB at Harvard University, noted that today art historians will often need to travel from several galleries, museums, and archives in order to gather the strands of a story about a particular artist, particular genre, and particular period.

“We want to facilitate the research activity of a scholar who wants to tell those stories across an institutional context so that rather than spending five years visiting 25 institutions, they could have access to the data of those various institutions in one place,” he said.

He noted that while diverse institutions feature objects from similar periods in history, they may interpret that history differently. As an example, he noted that all institutions agree there was a Byzantine era, though not all agree on a start date or end date. Where one researcher might want to have a numerically specific date, another might be interested in how various institutions have defined Byzantine.

He said that rather than proposing yet one more system to bring all of the museum systems into alignment, which hasn’t worked anyway, it would be better to provide a “roadmap” of how you can bring the various data into agreement or, if one chooses, eliminate the distinctions.

Battles said the NEH seed money—known as a discovery grant—was key, since the resulting research would be a public good that could impact the way stories are told at exhibitions, in elementary school classrooms, and in higher education, all of which would be “more richly informed by a broader array of resources.”

]]>

“We had a record-breaking Giving Tuesday,” said Elaine Ezrapour, director of the Fordham Fund. “It’s very exciting to see the outpouring of ‘phil-‘Ram’-thropy.’”

Held this year on Dec. 3, Giving Tuesday, the Tuesday after Thanksgiving, has become an international day of charitable giving. Since 2015, Fordham has raised hundreds of thousands of dollars each year on this day. But 2019 marked the first year that the University raised more than a million.

Supporting Athletics

The majority of the 1,589 gifts made this year were for Fordham athletics. More than $300,000 in gifts will help support the Frank McLaughlin Family Basketball Court and University sports teams. That includes the Fordham men’s rugby football team, which is raising money to fly to Ireland for the club’s first international tour in more than 50 years.

“Working with the Fordham Fund, we’ve created a Give Campus page for each of the varsity and club teams,” said Edward Kull, senior director of development and senior associate athletic director, adding that the student-athletes and coaches create videos for their teams letting everyone know what their needs are. “So it’s a real collaborative effort.” Squash, crew, football, water polo, and sailing were among the top raisers, he said.

Scholarships for Urban Plunge

More than $6,000 was raised for scholarships for Urban Plunge, a pre-orientation program where first-year undergraduate students participate in community service activities throughout the Bronx and Manhattan. The program, run by the Center for Community Engaged Learning, requires a $250 fee for each student that pays for their meals, transportation, and supplies.

A Double Giving Challenge

This year’s Giving Tuesday offered Rams a double challenge. If 350 donors made a gift by 11:59 a.m. EST, then Susan Conley Salice, FCRH ’82, and Thomas P. Salice, GABELLI ’82, would contribute $20,000. After the goal was achieved, the Salices presented the second half of the challenge: If 200 more donors made a gift by 11:59 p.m. EST, the couple would give another $20,000 to Fordham. Thanks to 550 donors, both challenges were met and the Salices donated $40,000.

Student Support

Students across the University helped spearhead donation efforts, too. In O’Hare Hall, student callers reached out to dozens of alumni, parents, and friends of Fordham. Usually, they work three hours a day, Ezrapour said. But on Giving Tuesday, they worked from roughly 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. and secured 150 gifts over the phone.

Further downtown, the Student Philanthropy Committee at Lincoln Center set up a tabling session in the Lowenstein Center. For the first time, they created a “giving tree” fashioned out of chicken wire and multicolored leaf cut-outs. Committee members asked passing students to write on a leaf the things they are grateful for at Fordham—including causes they want to support in the future.

“They wrote wonderful notes about the different areas on campus that they feel connected to and care about,” Ezrapour said. “It was a great effort on their part, not only in raising awareness about Giving Tuesday, but also demonstrating to the campus community just how many potential areas there are to support.”

The roughly $150 million in revenue bonds for the campus center project will be issued by the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York for Fordham.

“Both rating agencies note Fordham’s solid enrollments, our prudent management, recent enhanced financial stability, and capacity to manage this additional level of debt,” said Martha Hirst, Fordham’s senior vice president, CFO, and treasurer.

In its annual rating report released on Nov. 19, Moody’s assigned an A2 to Fordham’s proposed bonds as well as its outstanding bonds, and rated the University’s outlook as stable. The positive rating reflects Fordham’s “relatively large scope of operations and very good strategic positioning as a prominent Jesuit institution located in New York City offering a diversity of undergraduate and graduate programs,” according to the report.

Also noted in the Moody’s report were three other positives: Fordham’s increasing enrollment supports rising net tuition revenue, which, in turn, boosts the University’s operating performance. The University’s operating cash flow margin was “a sound 15.5%” in fiscal year 2019. And, surplus operations and strong donor support, with three-year average annual gifts that amount to more than $65 million and well above a peer median of $23 million, continue to build reserves.

Standard & Poor’s (S&P) Global Ratings assigned its “A” long-term rating to the revenue bonds and affirmed its “A” long-term rating on Fordham’s outstanding bonds. The agency’s Nov. 25 report also rated Fordham’s outlook as stable.

Similar to the Moody’s report, S&P cited solid enrollment growth and student quality as evidence of Fordham’s strong enterprise profile. Also noted were the University’s “consistently positive operating margins, concentrated revenue base, solid cash and investments relative to operations and debt, and improving expendable resources.” With regards to Fordham’s “solid management,” the report noted “conservative budgeting practices, success in implementing multi-year strategies, and well-considered reactions to external change.”

The proposed bonds represent the majority of the funding for the campus center project. As the centerpiece of the University’s new campaign focused on the student experience, the project will also be supported with fundraising dollars.

]]>It might seem like the last place anyone would choose to be. But for those like Michelle Charles, GSS ’15, with a background in palliative care, it’s exactly where she wants to be. Charles graduated from the Palliative Care Fellowship program at Fordham’s Graduate School of Social Service (GSS), one of a handful of programs of its kind nationwide. Today she is an oncology social worker at Memorial Sloan Kettering.

Charles’ upbeat demeanor belies the gravity of her role. Like so many in palliative care, a personal experience inspired her to get into the field; her grandfather died at home when she was applying to graduate schools.

“We dropped everything and we moved into his house, me and my parents, my sister. He was on hospice care and we were all there to take care of him,” she said. “That was kind of the experience that really propelled me to apply to grad school.”

She said when she heard there was a palliative care fellowship at Fordham, “it just clicked.”

“There are certain people who are lucky enough to not be facing this right now, but we all face this; there’s suffering for all of us in life, there’s death at some point for ourselves and for people that we love,” she said. “For me, getting to come here every day, I get to be really intimate with that and it takes away a lot of my fear.”

What Is Palliative Care?

The World Health Organization today defines palliative care as a health care “approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.”

The Palliative Care Fellowship

The Palliative Care Fellowship began at GSS in 2013. Acceptance as a Palliative Care Fellow is highly competitive and intended for students who are certain they want to work in palliative care. There are two required courses: One is Palliative Social Work, which deals with basic practices and principles, policy issues, and clinical issues. The second is Grief, Loss, and Bereavement. Students also have a dedicated field seminar led by an experienced palliative social worker. Cathy Berkman, Ph.D., associate professor of social work, is the director of the Palliative Care Fellowship and has been in the field since the mid-1990s. Berkman is a constant presence throughout the program for fellows, meeting them for lunch once a month, advising them during the fellowship year, and assisting with their careers after graduation.

Berkman recalled the early days at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Greenwich Village, when she worked on several large studies as a co-principal investigator with the hospital’s chief of geriatrics before securing a grant to establish an interdisciplinary palliative care service at the hospital.

She said that a large multi-site study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1995 presented a grim picture of the care given to terminally ill patients in hospitals; their wishes were largely unknown by their physicians. In the years that followed, as the medical field refined the practice of palliative care, social workers staked out their unique role, bringing their expertise in providing biopsychosocial and spiritual support to the table.

By 2010, a new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that cancer patients who received palliative care at the same time as their usual cancer treatment lived several months longer and suffered less from depression. Today there are more than 1,300 programs registered with the National Palliative Care Registry.

“Palliative care does not compete with the curative care that’s being attempted, it adds to it to enhance people’s lives,” said Berkman.

With social workers filling the role of intermediary between doctors, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and family members, she said, patients now have a continuous presence throughout their illness, a professional who can provide support and act as an advocate to help them see their wishes carried out.

From Fighting to Living

Sophie Rivera is currently a palliative care fellow doing her field placement at Montefiore Medical Center’s Wakefield Campus in the Bronx. Her supervisor there is Kenneth Meeker, GSS ‘12. On a recent afternoon, the two came together for an interview in the hospital’s Caregiver Support Center. The room is bathed in natural light, the sound of a small waterfall wall splashes in the distance, and boxes of tissues never sit more than an arm’s length away.

“I will tell you every family that we work with says that their loved one is a fighter because that’s part of their hope,” said Rivera. “And this is a touchy thing because we have to talk to the patient about what they would want and sometimes it’s not congruent with what the family wants.”

Rivera speaks from personal experience. Her mother died of cancer at Montefiore’s Weiler campus, also in the Bronx. She said that sometimes it’s helpful for families to let patients know it’s OK for them to choose to forego painful treatment.

“At the beginning, my mother was, ‘Let’s try for everything,’ but then I noticed in her that she looked tired; the chemo was just too much,” she said. “There was a point I had to have the talk and say ‘It looks to me like you’re just trying your best to maintain yourself because of me.’ I had to alleviate her of that because I didn’t want to feel that guilt either.”

She said she had a remarkable palliative care experience at the hospital that brought her full circle back to Montefiore, but this time as a practitioner.

Shifting the dialogue from one of a battle to one of acceptance requires a great deal of delicacy and trust, said Meeker. It falls to the palliative care social worker to ascertain what the patient wants and communicate to them what is possible.

“I teach my students from the beginning, you’ve got to connect with the families and the patients,” he said. “If you don’t connect, there’s nowhere to go.”

He said building a rapport can start with sports, music, or anything that’s not related to the crisis at hand.

Discussing the Inevitable

Unless something acutely traumatic happens, no one should ever have to say that didn’t know that a loved one was about to die, unless they choose not to be told, said Berkman. Patients and their families should be able to prepare for the end by facing the truth pragmatically, and that preparation should never wait until the opportunity has passed.

“There are several things you may want to be able to say to family and friends before you die; you want to say ‘I love you”, ‘I forgive you’, or ‘I’m sorry’,’” she said. “Those are things that may have accumulated over a lifetime. You need time to say all those things and by not knowing what your prognosis is, you’re deprived of the ability to have those conversations with people that you care about.”

All too often discussions about the realities of disease advancement get usurped by a battlefield culture around terminal illnesses and the rhetoric that goes with it.

“‘She lost her battle against cancer’ is terrible language and many people in this field really try to fight against that,” said Berkman. “It doesn’t matter how strong your will is and how much positive thinking you do, these are cancer cells or this is heart disease. Being stoic or thinking about unicorns and rainbows is not going to chase it away.”

At some point, palliative care social workers will facilitate a conversation with the patient and their families about the future. For some, that future could mean stopping disease-directed therapies and beginning to shift toward comfort care. For others, it could mean even more aggressive treatment that brings hope of a cure, but also pain and other distressing symptoms. The palliative care social worker must have a holistic understanding of the patient and family, including the medical and psychosocial issues, and then synthesize options and challenges so that the patient can make an informed decision about their future, said Berkman.

Palliative care should be offered from the moment of diagnosis of any serious illness so that patients have time to grapple with the entire arc of the disease—not just the late stages. Ideally, doctors would continue to deliver curative treatment as long as this is effective and desired by the patient, while the palliative care team helps the patient address pain and other physical symptoms, she said, as well as anxiety and depression, their spiritual needs, and social and financial issues that could affect their decisions. But that’s not always the case.

“Unfortunately, the specialist treating the illness with a curative goal in mind often does not refer patients to palliative care,” she said, noting the medical profession’s still-nascent view of palliative care. “Many still see it as not compatible with curative care or equating palliative care with hospice care and therefore as premature, or ‘giving up.’”

Living at the End

Kasey Sinha, GSS ‘19, received the prestigious post-MSW palliative care fellowship in the Division of Palliative Care at Mount Sinai Beth Israel near Union Square in Manhattan.

When Sinha’s grandmother was dying three years ago, Sinha read Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’ seminal book On Death and Dying, which famously outlined the five stages of grief (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance). From that moment she was drawn to the profession.

“I started doing research and came across palliative care, and was so moved by it,” said Sinha. “I felt like I had finally found my calling.”

She noted that everyone approaches the end of life in their own way and she feels privileged to bear witness to that.

“I love talking with people about their lives, how they’re coping, and what they’re struggling with,” she said. “As clinicians, we only see a small part of someone’s life, and being able to learn about them as a person, and not just as a patient, is a pivotal part of this work.”

A lot of patients who don’t believe in an afterlife take time to review their past and think of what their life means to them, she said. Other patients who believe in an afterlife look beyond their time on Earth.

“I often hear people talk about what they think heaven is like, or saying that they’re so excited to be reunited with people they love,” she said.

And still others are not ready to face mortality and want life-prolonging measures at all costs.

“Again, it’s really sort of understanding where the person is coming from and what they want, like if they want to hear serious news or how they want to hear it, so we ask a lot of questions,” she said.

Amidst the pain, Sinha finds beauty.

“People always ask me, ‘How can you do this work? It sounds so sad.’ But there is so much joy in seeing how much people love each other. So when you’re meeting someone who’s coping with a very serious diagnosis or you’re working with a family whose loved one is at the end of their life, being able to witness the love and care that they have for one another is incredible.”

]]>Four years ago, the University committed to Generation Study Abroad, an initiative spearheaded by the Institute of International Education, to double the number of students studying abroad. At the time, 36% of Fordham undergraduates studied abroad. This month, the institute officially recognized Fordham for passing the 50% threshold.

Joseph Rienti, Ph.D., director of Fordham’s International & Study Abroad Programs, said hitting that number was key to fulfilling Fordham’s goal of educating students to be leaders in a global society.

“It’s one of the best ways we find students can broaden their knowledge of themselves, of their academic discipline, and the world around them,” he said.

“It gives them an opportunity to experience a different culture, a different academic context, and it really just brings that global dimension to their undergraduate education.”

The increase didn’t happen by accident. Rienti said the department underwent a reorganization as part of the push to increase participation. Specific areas of study, such as short term-programs, exchanges, and the London Centre now have individual staff members dedicated specifically to managing them. Outreach has been overhauled as well, and the department now recruits students to be “global ambassadors” and gives them Canon Rebel cameras to document their study abroad trips.

“We think it helped. It’s really given us an opportunity to capture what the students are seeing and doing, and to share with students here in New York, to get them excited about going,” he said.

The new London Centre campus has had a palpable effect, Rienti said, as it enabled his department to offer additional programs, including one connected to internships. The University’s study abroad program in Granada has also expanded in the last three years. Rienti said his department has also worked with faculty to both develop summer courses abroad and add international components to courses that take place in New York.

Exchange programs are also a key area of expansion; most recently Fordham has established two with Institut d’études politiques de Paris and the University of Helsinki in Finland. And just as importantly, Rienti said all of the

26 exchange programs have been designed so that students can tap into the financial aid packages they use in New York City, making cost less of a barrier.

“What we’ve done is very strategically look to expand those opportunities, aware of the fact that we could make studying abroad sometimes even less expensive than studying in New York,” he said.

The department has also distributed an additional $50,000 in aid to students last year, thanks to a fund maintained by donations from parents, alumni, and even current students who want to help their peers.

“Sometimes students still have airfare to pay for, there’s still visas to pay for, and we’re able to give some additional funding to students,” he said.

Participating in Generation Study Abroad was helpful, he said, as it added another level of accountability to the department’s goals.

“We had to report back to the institute, and we were able to participate in conversations with other colleges and universities how to come up with innovative ideas and different strategies to get participation up,” he said.

Many students at Hayes—as the school is known—are potentially the first in their families to attend college. Most are Hispanic and African-American, and many come from single-parent homes in the South Bronx whose families struggle financially, said the school’s principal, William Lessa.

Four years ago, Fordham developed a partnership with Hayes that began with a mentoring program and has expanded to include work with WFUV, the Gabelli School of Business, the Graduate School of Education, and Fordham-based Jesuits. The collaboration has evolved into a symbiotic relationship between two schools that share similar missions and values, said staff from both institutions.

“Our partnership with Cardinal Hayes is a critical one,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “Students cannot aspire to a life they do not know exists, and they cannot achieve that life unless they are taught that it belongs within their grasp. If that were the only reason for the partnership, it would be enough. But engagement with the Hayes students, their families, and their community also enriches Fordham. We are wiser, better grounded in the lives of our neighbors, and the beneficiary of great talents that would otherwise go untapped, were it not for this partnership.”

The ties between the two schools have given Fordham students a window into what life in the South Bronx looks like, said Roxanne De La Torre, FCRH ’09, GRE ’11, director of campus and community leadership for Fordham’s Center for Community Engaged Learning.

“For our students to get more exposure to the Bronx—the South Bronx, in particular—for our students to get out of our campus and meet people who live and work and go to school here in the Bronx, is a huge positive,” said De La Torre, who helped drive the partnership between the two schools.

And for many young men at Hayes, exposure to Fordham’s staff and students has broadened their horizons and opened doors.

“Our kids are fascinated by them … They have no idea who lives out there,” said Lessa, adding that the partnership is also important to his students’ families. “I think our parents have decided to invest a considerable amount of money into their sons’ education in the hopes that they’ll be the first person in their homes to go onto college. Education is transformational and can be a change agent in their lives.”

‘The Best Tutor’

Several days a week, Fordham students visit Hayes and tutor students in an after-school academic support program called Period 9.

“Although [the Hayes students are] tired from a full day of classes, they attend Period 9 so they can get that extra help they need in a particular subject,” said Emily Padilla-Bradley, the school’s dean of studies. “Throughout the years, I’ve realized that the students have learned to appreciate, more and more, the help from the tutors from Fordham.”

One of those tutors is Manuel DeMatos, a Fordham College at Rose Hill senior who will be studying adolescent education at the Graduate School of Education next year.

“Just knowing that you’re having a positive impact and that these kids are improving their potential life—not just in high school, but into the future—is super rewarding,” said DeMatos, who wants to become a high school social studies and French teacher.

The Cardinal Hayes students in Period 9 are an eclectic bunch. There’s Calvin Lanier, a junior who plays football. There’s Leonel Nepomuceno, a senior who sings in the school choir and loves animals—including his three pets, Hailey the miniature poodle, Joshua the orange tabby cat, and Rango the turtle—so much that he’s considering studying veterinary science in college. Then there’s Albert Alexander Almanzar, a self-described class clown who often played around instead of focusing on his studies. But his years at Hayes—and a Fordham student named Thomas Bradley—changed him, he said.

Almanzar called Bradley, a student at the Gabelli School of Business, “the best tutor.”

“[He] gives me more motivation to want to do better in my classes because it shows me somebody that cares,” Almanzar said of Bradley, who tutored him in U.S. history and writing. “All day in school, people show that they care. But somebody that’s a little younger, I feel like I could relate to more… that means more to me.”

Finding A Passion for Public Radio

For the past three years, members of WFUV, Fordham’s public radio station, have paid an annual visit to Cardinal Hayes and, in a conversation with the entire junior class, shared what the students can learn at the station.

“There is this station that is right within their borough, within the University, that offers the kind of opportunities that they’re not going to find at other colleges and universities across the United States,” said Chuck Singleton, general manager at WFUV, which is ranked among the top 20 college radio stations by the Princeton Review.

Those visits have led to three paid internships for Hayes students, including Ramon Liriano, a senior who worked in the sports department last summer. Like many of his high school peers, he’s potentially the first in his family to complete a college degree. Thanks to his internship at WFUV, he said, he’s also discovered a potential career in sports broadcasting.

“I’ve seen my family struggle, especially my mother, who works two jobs [as a housekeeper]. I’ve seen her come home looking tired, especially late at night—sometimes, 1 or 2 o’clock in the morning,” said Liriano. “She’s put me in a Catholic school, pushed me to become better than what she has done in her life … I want to take this opportunity to study something really good in the world that can help provide for my family.”

Giving Students A Voice

Last year, a dozen Hayes honors upperclassmen took a corporate communications course through the Gabelli School of Business. From fall to spring, they learned how to deliver the perfect personal elevator pitch and put together an engaging presentation. They analyzed a Fortune 500 company that experienced a diversity-related crisis, like Starbucks, and presented a new diversity plan to their classmates. But perhaps most importantly, they learned how to become better communicators.

“The difference in how the students presented their work in class, how confident they were in their verbal responses, how confident they became in their social circles, all based on the communication competencies they learned in class … that, to me, was the most rewarding thing,” said Clarence Ball, lecturer and interim director of diversity, equity, and inclusion at the Gabelli School of Business, who teaches the course at Cardinal Hayes.

Five students from the initial cohort of Ball’s course are now first-year students at Fordham, including the 2019 Hayes valedictorian, Andy Lin.

Lin described himself as a shy student, who, as a high school freshman, used to read his speeches word-for-word from a piece of paper. Instead of making direct eye contact during presentations, he would look down. But by the end of Ball’s program, he saw a huge change in himself.

“Before I went up on stage to give my [valedictorian] speech, I did the exercises that Professor Ball always had us do,” said Lin, now a first-year Fordham College at Lincoln Center student who plans on studying computer science. “I messed up a few words here and there, but I was able to recompose myself and keep moving on.”

These relationships that Fordham professors and students are fostering in the community are something the University hopes to build on, said Michael C. McCarthy, S.J., vice president for mission integration and planning, who helped found the Center for Community Engaged Learning. Using its Hayes relationship as a model, Fordham is now working on a similar partnership with Aquinas High School, an all-girls Catholic high school in the Belmont section of the Bronx.

“My hope is that our partnership with Cardinal Hayes is one of many such partnerships with institutions in the Bronx, where students can engage their community more effectively,” said Father McCarthy. “We want to help faculty leaders to connect with community leaders to build up student leaders.”

[doptg id=”164″]Trading Teachers Across the Bronx

Several Hayes teachers have studied at the Graduate School of Education, thanks to the support of a Fordham scholarship that almost halves tuition costs for full-time professionals in faith-based non-public schools, said principal William Lessa.

And in the past three years, three Fordham-based Jesuit scholastics have volunteered at Cardinal Hayes. These young Jesuits who have just finished novitiate are deepening their faith through local community service, said Joseph O’Keefe, S.J., GSAS ’80, a current scholar in residence at the Graduate School of Education and Fordham trustee who was just chosen to lead the new USA East Jesuit province.

“The idea is to work in the Bronx community and to reflect on that as part of their preparation to become priests,” Father O’Keefe said.

At Hayes, the scholastics have counseled students dealing with tough situations at home, taught religion classes, and helped seniors navigate the college admission process.

“They’re there to help. But they also learn from people’s experiences,” said Father O’Keefe.

An Alumnus from Both Schools

At the heart of the partnership between the two schools is Donald Almeida, Fordham trustee and retired vice chairman of PwC.

Almeida, who grew up in Yonkers, New York, is a ’69 Hayes and ’73 Fordham alumnus who now serves on the boards at both schools. Over the past several years, he has spearheaded the partnership between his two alma maters and, with his wife, supported many students—including young men who have experienced homelessness.

Among his mentees is a Hayes student whom Almeida chose not to identify by name. The student plays basketball so well that he will likely receive many Division I offers, said Almeida, who has attended his sports games and cheered him on from the sidelines. He’s also occasionally taken the student and his mother out to dinner.

“I’m his ‘bro,’” said Almeida. “That’s what he calls me.”

A while back, Almeida learned that the student was considering leaving Hayes and attending a prep school, in hopes of being recruited by better college sports teams. But Almeida said he was more focused on getting the student into the best academic college program.

Almeida recalled the day he sat in his Rhode Island home, gazing at the ocean, when his cell phone rang. It was the student’s father. For two hours, they debated whether or not the student should stay at Hayes.

“Thirty seconds after I hung up the phone with his father, [the student] calls me to tell me he’s staying at Hayes,” said Almeida, noting that the student is not the only one benefitting from their relationship. “The more you impact their lives, the more satisfaction you get.”

]]>

Gregory Donovan, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Communication and Media Studies and co-founder of the Fordham Digital Scholarship Consortium, organized the conference with department chair Jacqueline Reich, Ph.D.

Instead of paying a fee, conference-goers were asked to send donations to Goddard Riverside at Lincoln Square Neighborhood Center, which offers services to the Amsterdam Houses across the street from Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus.

Digital mapping is a process that merges data with maps to create a virtual online image that can be static or interactive. Donovan said focusing on social justice issues through the lens of digital mapping allowed for a cross-disciplinary approach that wouldn’t ordinarily be found at a typical geography conference. Professors came from a variety of disciplines, including history, art history, urban planning, Latinx studies, psychology, social work, and education.

“Spatial media have politics, these are not neutral things,” said Donovan, who teaches a course of the same name as the conference for the Masters in Public Media. “We need to look at how our subjects are using digital mapping in their own lives and not just use this technology to study them from afar, like a scientist with a clipboard.”

In panel titled “Mapping the Local: A Focus on New York,” Jennifer Pipitone, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychology at the College of Mount St. Vincent, and Svetlana Jović, Ph.D., assistant professor of developmental psychology at SUNY Old Westbury, presented research that essentially handed the digital “clipboard” over to the Bronx Community College students they were teaching —and studying. At the time, the two were writing fellows at the college.

In an effort to map what “community” meant to the students, the researchers used geo-locations of photos taken by the participants “in order to illustrate and make sense of their experience of belonging in the city,” they wrote in the abstract. The maps revealed that students restricted their movements to above Central Park, “delineating participants’ lived boundary of race and class.” The method is referred to as “participatory action research.”

Throughout the conference, dozens of examples were given on how mapping technology can be used to heighten consciousness and problem solve. Adam Arenson, Ph.D., associate professor of history at Manhattan College, also on the Focus on New York panel, talked about how he worked with his students to help map slave burial sites in the Bronx, many of which sit unmarked on New York City parkland.

“These are all ways to memorialize the injustices of the past, to map them in the landscape and to be aware of them,” he said. “Though the information is incomplete, and we must do what we can to fill out the map, make the connections, and demonstrate how the injustices of slavery still shape New York City today.”

In her keynote address later that day, Sarah Elwood, Ph.D., professor and chair of geography at the University of Washington, took a theoretical look at how mapping with communities through participatory methods helps “unprivilege the map,” thereby making it less of a colonial process.

As one of the early theoretical thinkers in the field of geographic information systems, known as GIS, she said she is still learning how to infuse her work with “critical race thought” that has surged in academia over the past five years. After the lecture, she recalled a moment at a mapping justice conference in Baltimore when she noticed the diversity of the participants.

“I looked around the room and I realized that it was a different room than one that I had ever been in, in this critical mapping world,” she said. “It was full of activists and young scholars and people of color, queer folks, thinking and theorizing in ways that were not part of my first 20 years in this field.”

She called the moment an “epiphany.” She said while she continues to incorporate Marxist critique that allows her “to get at some structural processes of inequality” in mapping, her work is now heavily informed by black feminism, queer theory, and Latinx studies.

“Once you’ve had an epiphany like that, it’s like, ‘Well, duh, obvious!’ but yet, you’re also embarrassed that it’s taken so long for this epiphany to happen,” she said. “I always think, in those moments, ‘Thank God we have our whole life to become ourselves.’”

]]>

“African and African American Studies is not merely for Africans or African Americans; African and African American studies are American studies, studies of who we are, who we wish to become,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “It is, I think, a great sin for people who really don’t want to listen to what the African American experience can and must tell us … We have much to learn and much to celebrate.”

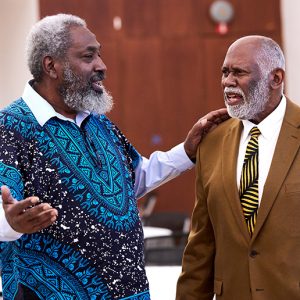

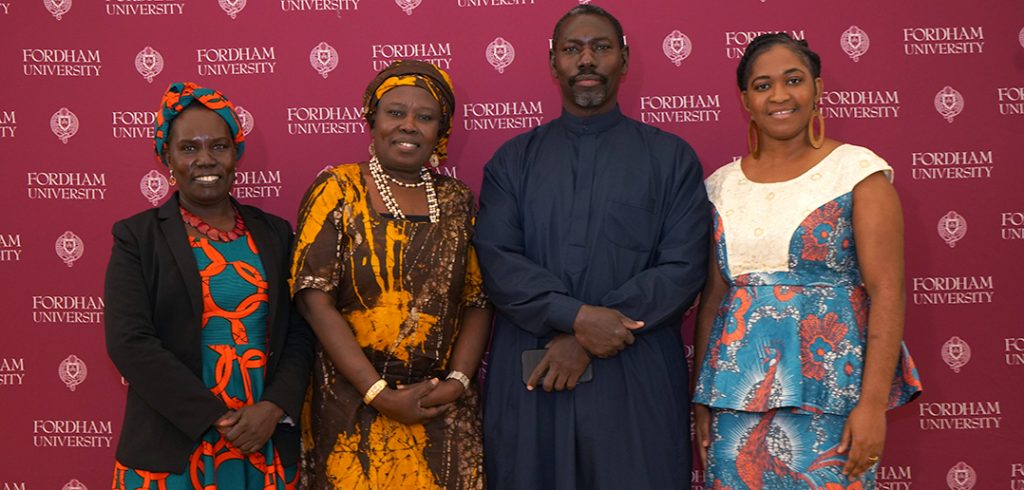

Organized by Amir Idris, Ph.D., professor and chair of African and African American Studies, the day began with a panel of founding faculty members who discussed the challenges they faced forming the department in the early days amidst national strife. A group of Bronx African community members later testified to how research conducted by a Fordham professor has helped bring much-needed services to their community. Another panel on emerging scholars on Africa and the African diaspora from across the University debriefed the crowd on their latest research. And Farah Jasmine Griffin, Ph.D., chair of Columbia University’s newly formed African American and African Diaspora Studies, took a comprehensive look at the current challenges and hopes for the future.

By day’s end, Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of African and African American Studies, the longest active member of the Department, who joined its faculty in fall 1970, was deeply moved by the panels’ trajectory. He spoke of the value research can have on communities of color.

“It really makes you realize what we’re doing matters,” he said. “It makes a difference.”

Hurdles of Coming into Being

Moderated by Naison, the first panel featured the department’s founding faculty talking about incidents that are fairly well known in the University community, such as the student protests that led to the formation of the department at Rose Hill, when nearly a dozen African-American students refused to leave the office of dean of student affairs until an agreement was reached to create an African American studies curriculum.

Perhaps less known was the concurrent development of the department at the Lincoln Center campus. Three faculty from Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC), Irma Watkins-Owens, Ph.D.; Fawzia Mustafa, Ph.D.; and Selwyn Cudjoe, Ph.D., recalled a department that had to make its way with little funding at the then-brand-new campus.

Cudjoe said it was a student movement that brought black studies to FCLC, adding that students were also very involved in the hiring of the faculty and selecting the courses. He said offerings were limited and students were recruited from Harlem, Bedford Stuyvesant, and the Bronx.

“There was no blueprint for building and sustaining a department like this,” he said.

Mustafa recalled that the formation of the FCLC department took place well before the restructuring that wove together faculty from the two campuses. Not only was the FCLC faculty autonomous from Rose Hill, but the African American studies department was less integrated with more established disciplines at FCLC as well. Resources were thin. Grant writing and fundraising became the only ways to bring some of the great black thinkers to campus. Watkins-Owens recalled relying on the library’s budget to build up the resources on African and African American content—a move that prompted an appreciative thank you note from the librarian for filling in a major gap in the collection. Watkins-Owens concurred with Father McShane on the importance of African American scholarship to all students.

“Black studies are for everyone, although some might try to lessen its importance in the current political climate,” she said.

Watkins-Owens said there is cause for concern for the discipline’s future, which may be reflective of overarching concerns for the survival of the liberal arts generally. She noted that there were more than 600 African American history programs in 2013 and that number has dipped to 361 programs nationwide. She urged “caution, vigilance, and activism.”

Research Affecting Communities

During a panel session with African community leaders from the Bronx, Sudanese native Jane Edward, Ph.D., clinical associate professor, moderated a discussion on how research could be used to help communities, not merely help researchers.

In 2006, Edward joined the Bronx African American History Project to engage the growing community. She and Naison went to events, schools, and organizations, eventually gaining trust. An ethnographer by training, she compiled a list of African establishments that contribute to the vitality of the city, including 19 mosques, 15 churches, 20 businesses, 19 markets, nine restaurants, six hair-braiding salons, six newspapers, four community organizations, two law firms, a women’s organization, a research institute, and a website.

Activist and community leader Ramatu Ahmet recalled how researchers often use her community to grab statements and data then never return to show them the results. Edward returned, again and again, to update the community on her progress, Ahmet said.

Christelle Onwu, a recruitment strategist with the New York City Commission on Human Rights, said that her background in social work helped her appreciate that little can happen on a policy level without good data, which she said Edwards’ paper, “White Paper on African Immigration to the Bronx,” provides.

“To convince an official you need to have numbers,” Onwu said.

“It is very difficult to make change without knowing what the needs are,” she said, noting the importance of research. But, she also warned, “It’s important that [researchers’] subjects don’t feel used, abused, or traumatized.”

To the Future

A forward-looking conversation among emerging scholars of the African diaspora prompted panelist Lauri Lambert, Ph.D., assistant professor of African and African American Studies, to state that she looked forward to when her fellow panelists will be referred to as “established scholars.” It was a fitting precursor to a keynote address delivered by Farah Jasmine Griffin, Ph.D., which examined the current state of the discipline, as well as the outlook for its future.

But first, she started by thanking Fordham for its past and expanded on other significant anniversaries that took place this year, including the 400th anniversary of the 1619 arrival of Africans in the Americas that laid the foundation for slavery in what would become the United States. She noted that while many of the year’s anniversaries were worth commemorating, Fordham’s was worth celebrating.

“This department represents the very best in the tradition of black studies, which through intellectual rigor and its commitment to social justice, seeks to do no less than transform the world,” she said. “And given that you all are one of the oldest and most successful departments you’ve served as inspiration for us at Columbia … [though]we are half a century late.”

She noted that she has been inspired by the work of early Fordham faculty, including writings by Watkins-Owens and Naison. She said that scholarship produced nationwide by African studies has enhanced traditional academic disciplines, especially history, anthropology, sociology. As she looked to the future she cited three sites of engagement for the discipline: in the classroom, in the world, and on the planet.

In focusing on the classroom, she spoke of a variety of contemporary theoretical perspectives including Afro-pessimism (how anti-black violence influences society), Afrofuturism (an Afrocentric intersection of science, history, and technology with utopian visions for the future), black feminism, black queer studies, and black performance studies.

“Now these are oversimplifications of these very rich and complex theories meant only to underscore their robust contribution to the original analyses of black life, culture, history, and the blessed nations,” she said after briefly explaining the theories. “Afrofuturism has been especially attractive to practitioners in technoculture, readers, and writers of science fiction, and some pop culture artists like Janelle Monáe,” she said.

And while she praised the new perspectives and the excitement they bring to students, she also raised concerns that they turn attention away from the dominant continental/European theories that can also serve to frame modern understandings of black life.

“One of the limitations [of the new theories]is the way that such students seem to strongly feel that there is little value outside what this body of work has to offer, resulting in, at best, a failure to appreciate earlier work or, at worst, a dismissal of it as theoretical or old fashioned,” she said.

In the speaking of the world perspective, she noted that few from the discipline were naive about racial progress expected after the election of Barack Obama.

“Nonetheless, in spite of this awareness, few of us, myself included, were prepared for the extent to which the pendulum swung backward in this nation,” she said. “The rise of right-wing, populist nationalism; naked white supremacy; and neo-fascism throughout the Americas, Europe, and Asia has been especially striking.”

When she focused on the planet and the role of Africana studies, she noted that climate change inordinately affects low-income communities of color around the world. She said too few lessons were learned from Hurricane Katrina, as thousands in Puerto Rico and the Bahamas remain devastated from storms there.

She called for a “greening” of Africana studies. “We need more work on the impact of climate change on poor communities and on Island nations, particularly in the Caribbean. And furthermore, we might explore ways that our own institutions can work with these communities on these urgent issues.”

Capping with Culture

While the majority of the day was filled with thoughtful dialogue, the panels and lectures were buttressed by performances of African percussion, singing, and dance by performers from Broadway’s The Lion King. During dinner, one could hear discussions about Muddy Waters coming from one table to Toni Morrison at another and Henry Louis Gates at a third. By the time the cake arrived, DJ Charlie “Hustle” Johnson had pumped up the music to bring the crowd to the floor. The evening was capped by a rap performance by Dayne Carter, FCRH ’15.

]]>

As Fordham celebrates the successful conclusion of Faith & Hope | The Campaign for Financial Aid, the University is transitioning to a new campaign dedicated to enhancing the overall student experience.

The centerpiece of the campaign will be a new campus center at Rose Hill that is scheduled to be completed in 2025. The campaign will also seek support for other student-focused issues like wellness, financial aid, athletics, and STEM facilities, which are being developed in the University’s strategic planning process.

“The new campus center will be bigger, both literally and in concept, than its current incarnation,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “It will be at the heart of the student experience campaign, and the student experience is at the heart of the University. In caring for the whole person, we want Fordham to be a place where students can live, learn, study, celebrate, dine, play, and perhaps most of all connect—with their peers and with the faculty and campus community.”

The campus center project, which the University began work on over the summer, will take place in two phases and cost an estimated $205.3 million.

A Dramatic Expansion

The first phase is scheduled for completion in August 2021 and will entail the construction of a roughly 75,000-square-foot addition in the area in front of the existing McGinley Center.

The sleek glass and stone addition will be connected to the existing structure via a two-story glass arcade, with elevated walkways between the two buildings. The glass canopy-topped main entrance will beckon visitors into an airy space between the Rose Hill Gym and the new addition. The center’s façade, once defined by the modernist arches of the McGinley building, will now be dominated by vertical, soaring windows and stonework that complement the neighboring Gym. In a nod to iconic Rose Hill structures such as Keating Hall and Duane Library, it will also feature a four-story illuminated tower immediately to the west of the entrance.

Once the addition is complete phase two will begin, and the existing structure, which was built in 1958, will be gutted and renovated. When it is finished, it will feature 22,000 square feet of dining facilities and 36,000 square feet of state-of-the-art sports and fitness facilities. Ultimately, the new campus center, which is being designed by the architecture firm HLW, will be much larger, encompassing more than double the space of the original building. It will also include efficient LED lighting, heat recovery systems, enhanced insulation, solar panels, and other features designed to lower its carbon footprint.

The expansion will allow for a dramatic increase in space for several areas. The 20,000 square-foot fitness center will encompass more than half of the basement level, while more than 16,000 additional square feet will be devoted to sports medicine and a varsity weights training center. A 9,500-square-foot student lounge will occupy the first floor of the addition, while Career Services, the Center for Community Engaged Learning, and Campus Ministry will be housed in larger offices on the second floor. The third floor of the addition, which will rise a floor above the existing McGinley Center, will feature space for meetings and special events.

Funding for the Center

Funding will come from a combination of fundraising, loans, and dining services provider Aramark, which has committed $13.3 million toward the renovation of the dining facilities. Fordham will borrow $150 million through a bond offering, and raise up to $85 million for the project through the next capital campaign.

Together, nine donors have already committed $10 million toward the Campus center. Maurice J. “Mo” Cunniffe, FCRH ’54 and Carolyn Dursi Cunniffe, Ph.D., UGE ’62, GSAS ’65, ’71, whose generosity in the previous campaign led to the creation of the Maurice and Carolyn Cunniffe Presidential Scholars Program, has given $3 million.

Other donors include Board of Trustees Chair Robert (Bob) Daleo, GABELLI ’72, and Linda Daleo; Trustee Fellow Emerita Kim Bepler; Trustee Emeritus Robert E. Campbell, GABELLI ’55, and Joan Campbell; former Trustee Stephen J. McGuinness, GABELLI ’82, ’91, and Anne McGuinness; Trustee Brian MacLean and Kathy MacLean, both FCRH ’75; Brian Kelly, LAW ’95; former New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg; and several anonymous donors.

The center will feature many spaces with naming opportunities. Among the high-profile spaces in the new building are the fitness center, arcade, career services space, and special events space. When refurbished, the original building’s main dining room, ballroom, and student affairs suite will be available as well.

A Positive Financial Picture

The bulk of the funding for the project will come from a loan that the University will take on through a bond offering via the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York.

Martha K. Hirst, senior vice president, CFO, and treasurer, noted that Fordham is able to do this in part thanks to the University’s solid financial footing. Last month, for instance, global rating agency Standard & Poor upgraded its outlook on Fordham from negative, which it issued in 2017, to stable, and affirmed its “A” long-term rating on outstanding bonds. The University previously borrowed $212 million in 2008 via bonds for the construction of the new Law School building; Hirst said it continues to be the best way to finance big projects.

A Focus on Students

Jeff Gray, senior vice president for student affairs, said the new campus center will dramatically increase the ability of the University to deliver the services and spaces that students need to thrive.

“We have clearly outgrown the current campus center over the years, and it’s going to bring online a lot of exciting new spaces that will improve the quality of life for all our students,” he said.

He noted that in recent surveys of students at Rose Hill, 60% indicated that current student club and programming spaces are inadequate for their needs, which is not surprising given that the center was built to accommodate just 2,500 undergraduates total, 850 of whom lived on campus at the time. Today, 3,500 students live on campus, another 1,000 live in off-campus housing and another 2,000 commute to campus. The new campus center will be a place where all of these students can come together to socialize and collaborate.

For a preview of the benefits to come, Gray pointed to the 2016 renovation of the garden level of the Lincoln Center campus’ 140 W. 62nd Street.

“There’s a retail dining facility there that’s very popular; there’s a large community lounge where students gather, study, and meet; there’s dedicated space for student clubs; and dedicated space for important student services, like the dean of students, student involvement, health services, counseling, and career services,” he said.

“They’re all located in that hub, and that’s had a very palpable, positive impact on the quality of life for our students at Lincoln Center. We hope to achieve some of the same benefits at Rose Hill on a larger scale.”

Studies have shown that the longer a student remains on campus and in an academic mindset, the greater their chances are for academic growth and success, Gray said, noting that student retention is a key priority for the University. The new campus center at Rose Hill, he said, will be designed to give students a better sense of place outside the classroom.

In addition to dining, fitness, student lounge, and career services spaces, Gray said he expects that students will benefit greatly from the improved office spaces for departments such as Campus Ministry, the Center for Community Engaged Learning, and the Office of Student Involvement, which supports student clubs and activities.

“Those services are certainly central to our mission and what we do, and I think all of those things have the net effect of improving the overall student experience for the students,” he said.

]]>SPC is a student-run organization at both the Lincoln Center and Rose Hill campuses. It offers opportunities throughout the year for students to give back to the larger Fordham community through their time, energy, and donations.

“[It’s] a group of dedicated students working to create awareness and educate their peers about the importance of giving back to Fordham and its community,” said Kathryn Mandalakis, FCRH ’19, former senior class gift chair and current Fordham Fund Officer. “Our mission is more than just fundraising—it’s more about creating buzz and passion about giving back.”

The committee kicked off giving season on Sept. 24 with its annual Thank-A-Thon, a four-day tabling effort that encourages students to write thank-you notes to Fordham Fund donors.

“One of the tenets we stress in our meetings is that it’s important to say thanks!” said Mandalakis. “It’s also just a great way for students to interact with our staff members and the Fordham community at large. We always ask students to write a thank-you note so they can more passionately support the cause.”

With the guidance of Fordham’s Office of Stewardship/Donor Relations, these Thank-A-Thon notes are sent to donors who support student scholarships, clubs and organizations, campus renovations, and other initiatives.

The Student Philanthropy Committee not only provides opportunities to thank existing donors but also offers students the chance to become a part of the larger community of donors themselves by making gifts to the causes that have been most important to their student experience.

“Being a part of the Student Philanthropy Committee allows me to talk to my peers about how impactful gifts of any size can be, and how impactful your time, energy, and focus can be in improving other people’s lives,” said John Morin, FCRH ’20, the Fordham College at Rose Hill senior class gift chair.

A few of the opportunities available for students to learn more about giving back and the benefits of becoming a part of the donor community are the Senior Class Gift Kick-Off taking place in November, followed by Giving Tuesday on Dec. 3, and Fordham Giving Day from March 3 to 4.

“Supporting the senior class gift is a great way to give back to Fordham before becoming an alum. It acts as a vote of confidence in a senior’s four years at Fordham and allows him or her to support the areas that have been most important throughout,” Mandalakis explained. “[It] also introduces students to the world of giving at Fordham in an approachable way while they’re still together with their classmates.”

Current seniors are encouraged to give $20.20 to represent their graduating year. However, seniors who give $50 or more over the course of the year are able to receive the benefits of Young Alumni President’s Club (YAPC), a giving society reserved for current seniors and alumni within 10 years of graduation. (YAPC alumni who have graduated within 1 to 5 years make annual gifts of $250, and for those who have graduated within 6 to 10 years, gifts of $500.)

Much like the President’s Club alumni, who have graduated within 11 or more years and have donated annual gifts of $1,000 or more, YAPC members are invited to exclusive donor receptions and celebrations hosted by Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. This year’s YAPC members can look forward to an invitation to the President’s Club Christmas Party, where they will be able to meet longtime President’s Club members. They will also be offered the opportunity to attend a YAPC reception in April and a cocktail reception during Jubilee weekend in June, and they’ll receive recognition in the University’s annual honor roll of donors.

“I love Fordham and what Fordham stands for, and I wanted to give back to this great institution,” said committee member Kaitlyn McDermott, FCRH ’21. “Joining SPC allowed me to find an outlet for philanthropic duties while learning valuable skills about being a woman for other people.”

–Chloe Meyer

]]>