“I was immediately interested in the internship because it combined my passions for content creation, marketing, and helping youth,” said Gonzalez, a senior at Fordham College at Rose Hill.

Gonzalez got the position through Serving the City, a paid internship program available only to students enrolled at Fordham College at Rose Hill and Fordham College at Lincoln Center.

Early Roots

The program began in 2020 with two partner organizations, the Museum of Art and Design and the New York Historical Society, under the title Cultural Engagement Internship Program. The goal of the program was twofold—students would gain experience and receive a stipend from Fordham, and nonprofit partner organizations would benefit from the support of an intern.

Though the program began with nonprofit institutions focused on arts and culture in New York City, it quickly grew to include other types of nonprofits serving the city’s communities. More than 60 students have interned with more than 35 organizations since it launched.

“Over the past year, we’ve really built out our partnerships,” said Desirae Colvin, director of administration, communication, and strategic initiatives in the Fordham College at Lincoln Center Dean’s Office, who manages the program at Lincoln Center and at Fordham College at Rose Hill. “After a certain point, we thought cultural engagement as the moniker doesn’t feel as reflective of that. We started to think, ‘What do they have in common?’”

That’s how the name Serving the City was born, Colvin said, to include the range and depth of internship opportunities and partner organizations.

Supporting Nonprofits Throughout the City

Arika Ahamed, a junior majoring in neuroscience at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, was one of the first to intern with a group outside of the arts and cultural organizations. She interned in summer 2021 with the Elmhurst Corona Recovery Collaborative in Queens—a group of about 25 nonprofit organizations that provided assistance and resources to residents impacted by the pandemic.

Ahamed helped create a pamphlet of resources, maintained and updated the collective’s website, and helped coordinate meetings across the coalition to keep members on track. One of her main goals was to help make the information accessible to those in need.

“One of the biggest things we noticed was that [the website]was all in English, which was something that we needed to work on,” she said. “So I was able to figure out a way to easily translate the entire website without having a translator, by connecting it to Google Translate.”

Ahamed said the internship gave her new skills in organization and communication.

“The biggest thing I think I learned from this was professionalism in general—I had to send out emails to over 75 people and at first, it was daunting because it wasn’t something I’ve ever done before,” she said.

Despite the expansion, the program still includes several cultural partners. When the pandemic forced the Chelsea Music Festival to move its events to a virtual setting, the organization needed help promoting its work, getting media coverage, and connecting with audience members. Enter Samantha Matthews, now a senior at Fordham College at Lincoln Center.

Matthews was the public relations and marketing intern during 2021, responsible for reaching out to media organizations for coverage and promotion as well as running the social media accounts.

“I enjoyed their mission of giving back,” Matthews said of the festival, which aims to “give emerging voices, particularly those of women and people of color, a stage” and support a community of musicians, composers, and artists. “At Fordham, our motto is to be men and women for others and philanthropy is a cornerstone of our education, so that’s something that’s important to me,” she said. “The fact that [the internship]also tied in music and it tied in art, was really appealing to me.”

Matthews said that the internship helped her realize that public relations is something she wants to pursue, which led her to her next two internships at Les Coeurs Sauvages, an ethical fashion brand, and Head & Heart PR. She also said that she’s grateful for the connections she made.

“I really enjoyed what I did, and the environment there,” she said. “I know what I want to do in life now, and I also have met people that I know that I could call if I ever need help.”

Equitable Opportunities for Students

One of the biggest benefits of the program, according to students, is that it provides paid internships, making it accessible to those from a variety of backgrounds. This was essential right from the start, according to Fordham College at Rose Hill Dean Maura Mast, who described the need for equity at a Homecoming panel in 2021.

“Fordham students, while they have a lot of internship opportunities in the city, they’re often unpaid,” said Mast. “Often students have to decide between taking an internship for credit and getting paid. We want our students to have access to these opportunities [no matter their financial situation].”

The Serving the City program began the year before Fordham publicly launched its $350 million fundraising campaign, Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, which seeks funding for this and other programs that help students discern their paths and form new career-building connections.

Serving the City “would not exist without the generosity of alumni and donors,” said Laura Auricchio, Ph.D., dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center. “It is 100% funded by individual contributions, and those contributions go directly and exclusively to student stipends.”

Donors to the program “double or triple their impact,” she said, by giving students a more educational alternative to minimum wage jobs, enabling nonprofits to augment their staffs with Fordham students, and helping the nonprofits advance their missions.

“The financial support for the internships is one of the linchpins of the program,” Colvin said. “It’s integral to what the program is for—ensuring that students can opt for something that they find meaningful and that they can be financially supported. Too often a choice of one or the other is made.”

Colvin said that since the program is run by existing staff in the dean’s offices, all donations go directly to supporting student internships without having to fund any overhead costs.

“This is truly you’re supporting this student to be able to do this internship,” she said. The program has a fund where donations can be made directly.

Caridad Kinsella, a senior at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, said that being paid for their internship at the Brooklyn Museum was a “top three reason” why they applied in the first place.

“I live in the city, I pay for college myself, I had a second job—so the fact that these internships exist and that they are paid, and that students are paid a fair wage for their work, that is hugely important,” Kinsella said.

Kinsella worked with the visitor experience and engagement department at the museum, specifically conducting background research for the exhibit on fashion visionary Thierry Mugler exhibit. Mugler, who The New York Times described as a “genre-busting” designer, was gay and embraced LGBTQ+ representation in many of his shows, even at times when it wasn’t popular.

“I enjoyed getting to do a lot of the research and writing [for the exhibit],” they said. “I’m a huge fan of fashion, and I like history, and I’m also queer—this work connects a lot of those things.”

A Launching Pad for Future Success

Kinsella said that one of the great things about the Brooklyn Museum was that it has a mentorship program that’s helping them navigate the transition from college to a full-time career. Kinsella’s mentor from the museum is helping them with reviewing their resume and cover letters and practicing for interviews.

Kassandra Ibrahim, a 2022 graduate from Fordham College at Rose Hill who is now pursuing her master’s at Sotheby’s Institute of Art, also interned at the Brooklyn Museum. Ibrahim used her experience working on the Andy Warhol exhibit to help get her next internship, working at the Met. Both internships informed her senior thesis project, which combined her interest in art history and theology.

“I think that this internship taught me that there isn’t really a hard line between art history and other disciplines,” Ibrahim said. “And it inspired me to come up with my senior seminar topic. I’m working on representations of early Christian women, and I thought of that topic while I was in the museum one day, because I thought, ‘Wait, I don’t have to choose one or the other.’”

Kinsella said that the internship opportunity gave them both hard and soft skills.

“There’s the practical connections and networking skills that you pick up, but there’s also the softer side of gaining the confidence to use those skills,” they said. “For me, it’s been a transformative experience, not only to connect to where I live in New York City, but also to the Fordham community.”

To inquire about giving in support of the Serving the City program or another area of the University, please contact Michael Boyd, senior associate vice president for development and university relations, at 212-636-6525 or [email protected]. Learn more about Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, a campaign to reinvest in every aspect of the Fordham student experience.

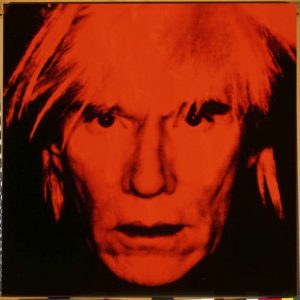

]]>One of the 20th century’s most influential artists, Warhol is more often associated with Studio 54 and his iconic painting of Marilyn Monroe than attending Mass. Scholars of his work know about his Catholicism, but to many fans, his faith is something of a surprise. That faith, and its manifestation in his work, is the subject of a recently opened exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum titled, “Andy Warhol: Revelation.” And, it’s a subject that many students and Fordham experts—in subjects from art history to theology to law—can weigh in on and learn from.

Catholic Versus Spiritual in Art History

“Warhol went into Catholic churches, so he wasn’t just generically quote-unquote ‘spiritual,’” said Laura Auricchio, Ph.D., dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center, who has published on pop art, most notably on Warhol contemporary Robert Rauschenberg.

“Unlike the Abstract Expressionists who poured and splashed their inner selves onto canvas, Warhol and Rauschenberg drew their imagery from the outer world of commerce and consumption, finding their sources in billboards, magazines, and television,” she said.

Auricchio added that the public doesn’t know much about the faith of 20th century artists because critics, curators, and historians of modernism have largely ignored it. Even a recent New York Times review of the show questioned the depth of Warhol’s faith by citing a biographer who dismissed it and highlighted instead his superstitious nature, pointing out that Warhol also wore crystals. The show, which originated at the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, is an important step to not just reexamine Warhol’s faith, but also the faith of modernist artists generally, Auricchio said.

“Van Gogh was actually a deeply religious person, and most people don’t know that, so it’s probably no surprise that people don’t know that Warhol was in a deep and complex relationship with his faith,” Auricchio said. “The history of modernist art has largely written religion out. It has not written spirituality out, but it has written religion out.”

Indeed, it wasn’t until after his death that Warhol’s faith was even acknowledged in public, and in true Warhol fashion it was revealed at the epicenter of New York Catholicism: Picasso biographer John Richardson talked about it at Warhol’s memorial Mass at St. Patrick’s cathedral, said Auricchio.

“It has taken quite a long time for that narrative to take hold and be taken seriously—and that’s something else that really struck me in this show,” said Auricchio.

The Serial Effect

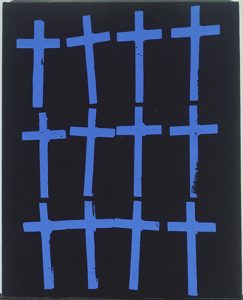

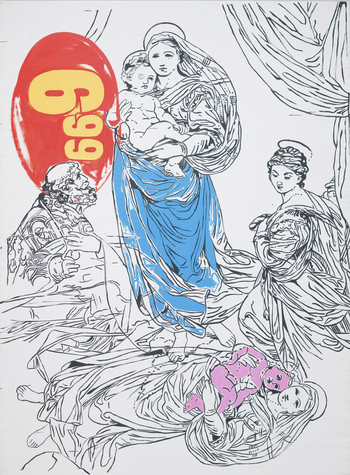

At the start of the Brooklyn Museum show, four icons of St. John, St. Andrew, St. Thomas, and St. Peter are arranged to mimic the altar screen from Warhol’s childhood church, St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church in Pittsburgh. Beside them are ephemera from Warhol’s Catholic childhood, including his baptismal certificate.

The museum text notes that the way the saints are arranged on screens typically found on Orthodox Christian altars impart a serial effect, like the repetition found in Warhol’s famed silkscreens of celebrities. Indeed, the next section of the exhibition features a series of eight blue canvases titled “Jackie” that reflect that repetition via a series of silkscreens of Jaqueline Kennedy’s face culled from press clippings from just before and after her husband’s assassination.

Appropriation as Art

In museums and art galleries, visitors are generally permitted to take photos for social media, but limitations are placed on photos for publication. Though Warhol frequently pulled photos from the newspaper to use in his own work, as he did in “Jackie,” using Warhol’s imagery of imagery is tightly controlled. Photos of “Jackie” were not permitted for publication.

It’s an irony that’s not lost on Raymond Dowd, LAW ’91, a partner at Dunnington Bartholow & Miller. Dowd is a member of the board of governors at the National Arts Club on Gramercy Park in Manhattan, where another show, “Andy Warhol Portfolios: A Life in Pop | Works from the Bank of America Collection,” closed just a week before the Brooklyn show opened.

Clocking in at more than 1,400 pages, Dowd’s book, Copyright Litigation Handbook (Thomson West, 2010), is a tome on the subject. He said that Warhol’s frequent appropriation—from Marilyn to Campbell’s Soup—probably couldn’t happen as easily today.

“The truth is that until the 1980s and 1990s, America had the weakest copyright laws in the world, which also unlocked tremendous creativity,” said Dowd. “We adopted restrictive copyright laws later on in the game and who knows whether or not that will truly restrict creativity?”

Dowd said that visual appropriation, whether by artists like Warhol, Richard Prince, Jeff Koons, or Shepard Fairey, is never going to be an entirely settled question. In many cases, he said, it’s beside the point. The very action of appropriation is often an artistic act.

“They’re playing with fire. They’re provoking those in power. They’re pushing the boundaries,” he said.

Opening Day: Fordham Deans and Interns

When “Revelation” opened to the public on Nov. 19, Maura Mast, Ph.D., dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill, joined Auricchio to see the exhibit along with two Fordham interns who had worked on the show from as part of Fordham’s Cultural Engagement Internship Program. The deans founded the program at the height of the pandemic; they were grateful to go to the museum in person and meet with students who had conducted research for the Department of Visitor Experience and Engagement.

“When I first learned about the new internship program, I realized that would be a perfect project for a Fordham undergraduate,” said Manager of Visitor Engagement Jessica Murphy, FCRH ‘91. “I recall that during my own time as a Fordham student, access to New York City’s museums and arts-related internships was invaluable.”

silkscreen ink on linen, 20 × 16 in.

“Revelation” weaves together art history, religion, gender, popular culture, and a New York context in a manner that Fordham’s liberal arts students are ideally prepared to contribute to and learn from, she said.

Indeed, both interns pulled from their Catholic and Byzantine backgrounds to examine and assist in the visitor experience.

Kassandra Ibrahim is a Fordham College at Rose Hill senior and an intern at the Orthodox Christian Studies Center. She said she was initially torn between pursuing art history over theology while applying for graduate schools, but she said the internship helped her come to an academic epiphany.

“I’d like to pursue art history, but I was always drawn back to my courses with the Orthodox Christian Studies Center because I’m interested in studying my own background. This show demonstrated that I don’t have to choose between two,” she said.

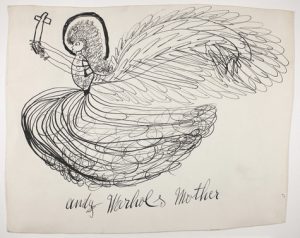

Fordham College at Lincoln Center senior Sarah Hujber learned a bit about her background as well.

“I grew up in a small two-mile-wide Polish town on Long Island, so I really related to his Eastern European upbringing and his wanting to move to New York and work in the art scene,” Hujber said. “I always related to that kind of wanting more and being in the busyness of the city.”

Hujber, who was tasked with researching the women in Warhol’s life, began to learn about the source and loss of many of her own family’s traditions. In examining Warhol’s mother, she viewed an Eastern European immigrant experience that was distinct from yet mirrored that of her family’s.

“I saw a lot of parallels between how my own family ended up here and the kind of traditions I heard about growing up,” she said. “We’re still Catholic, but we probably have lost some of the fullest traditions of Eastern European things that Warhol would have been a part of.”

An Icon’s Icons

Warhol’s parents, Andrej and Julia Warhola, immigrated to Pittsburgh from present-day Slovakia, a place that was once part of Czechoslovakia, which in turn was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Byzantine Empire before that. As such, the ever-shifting borders have little to do with Warhol’s ethnic identity, said Aristotle “Telly” Papanikolaou, Ph.D., the Archbishop Demetrios Chair in Orthodox Theology and Culture and co-founding director of the Orthodox Christian Studies Center. Warhol’s ethnicity has been variously described as Polish, Slovakian, and even Ukrainian—but his ethnicity was Ruthenian.

“I’m somewhat oversimplifying, but the Ruthenians were part of a group of Orthodox that are now part of the Catholic Church, who were able to keep their vestments, rituals, and married priests as long as they pledged allegiance to the pope,” said Papanikolaou. “Part of the Ruthenian heritage is an iconographic tradition and that’s one of the things that remains very much a part of them and why they’re sometimes called Greek Catholics.”

As mentioned, Warhol’s childhood church was indeed filled with Greek-influenced icons painted in the early 20th century and arranged in rows as part of the altar screen. But Papanikolaou noted that the four icons in the exhibit have a slight Western influence.

“Orthodox Christians went through a weird inferiority complex in the late 19th and early 20th century where their icons took on a bit more of a kind of naturalistic style. In other words, the figures evoke a bit of the Renaissance, but not in totality,” said Papanikolaou. “They melded these two traditions in ways that were really unique. It was only from the ’60s on where people started to go back to the original Byzantine style.”

Through her internship, Ibrahim learned about melding influences; she talked about how they carried on throughout Warhol’s work and can be seen in the show.

“He’s inspired by both the Byzantine aspects of iconography, and the iconic image of an individual in a one-point perspective, but then we see his Last Supper paintings [based on DaVinci’s]and you can see the influence of the Renaissance,” said Ibrahim, who was raised in the Greek and Coptic Orthodox traditions. “It’s kind of a mix because Byzantine Catholicism is also a mix. It is a fusion between an Orthodox visual reality and then Catholic doctrine. So, it’s in communion with the Catholic church, but visually it looks very Orthodox.”

‘The Symbol Is Everything’

Papanikolaou said that the flat one-point perspective of the early Byzantine icons is sometimes dismissed as being somewhat primitive, which does the artists and the church that commissioned them a disservice.

“They knew what they were doing,” he said. “They were trying to not look realistic because there trying to capture not just a historical event of the past but also point to an internal significance of the moment or a transcendent divine in the historical moment.”

Conversely, he said, an early renaissance painter like Giotto might paint the baby Jesus in a more realistic and cherubic manner to help the viewer to identify and participate in the earthly life of Jesus. Iconographers were not simply reminding believers of events, but rather they were symbols that allowed viewers to participate in an eternal reality.

“The symbol is everything, in a way, because the structure of the symbol really determines what it is that the viewer can participate in,” he said. “From that point of view, I can really see Warhol being influenced by that tradition. I think he’s trying to say that there is something of an eternal significance going on within these particular figures and even the particular events they’ve experienced in their lives.”

]]>