Now all it needs is a home.

With help from two of the University’s most generous donors, the center is well on its way to getting just that—a dedicated space at the Rose Hill campus, designed around the heritage and iconography of Orthodox Christianity, that acts as a leaven for new academic opportunities and student engagement.

The center has been mainly about research and publications since its founding 10 years ago, said George Demacopoulos, Ph.D., the Father John Meyendorff & Patterson Family Chair of Orthodox Christian Studies and one of the center’s two founding directors. However, with this new multipurpose facility, “for the first time we’re really going to be able to focus on the undergraduate students themselves” by providing spaces for informal gatherings as well as events that enrich their education, he said.

He and the other founding director, Aristotle Papanikolaou, Ph.D., the Archbishop Demetrios Chair in Orthodox Theology and Culture, are based at the Rose Hill and Lincoln Center campuses, respectively, and the center has held events in various places at both campuses.

The center will hold all but its biggest events in its new dedicated facility, Demacopoulos said. Located in the 1,500-square-foot space in the basement of Loyola Hall, it will include offices, a conference room, a gathering area, and a small chapel with specially commissioned icons, as well as shelves for hundreds of donated volumes now sitting in boxes. Demacopoulos estimated that construction and renovation of the space could begin in late 2023, putting the center on path to a more rooted existence and doing away with constant searches for event spaces around the University.

The new facility will be a familiar place where students gather for study groups or stop in at the chapel for some quiet reflection. Academic experts and clergy will come for webinars, panel discussions, and other events that illuminate questions of Orthodoxy in the modern world. “It’s going to really be this multipurpose space that is focused on the Jesuit model of integrating learning with faith with service and so forth,” Demacopoulos said.

Housed within a Jesuit university, the Orthodox Christian Studies Center is uniquely positioned to help heal the rift between the Catholic and Orthodox churches—something that was especially appealing to the benefactors who are funding half of the new facility’s cost.

Donors Step In

William S. Stavropoulos, PHA ’61, and his wife, Linda Stavropoulos, have been giving back to Fordham for years, funding scholarships, athletics, and the renovation of Hughes Hall to house the Gabelli School of Business on the Rose Hill campus.

Today, in recognition of the “unbelievable great job” Father McShane did as president of the University, they are making a major gift toward the completion of the Joseph M. McShane, S.J. Campus Center, a key part of the University’s $350 million fundraising campaign, Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student. As part of that gift, they are also setting aside $250,000 for the construction of the Orthodox Christian Studies Center’s new home.

Their giving is rooted in William Stavropoulos’ Fordham experience, which was, in his words, “a game changer.”

“When I entered the University, coming from a rural high school with a graduating class of 15, I was not sure that I could measure up. I had real doubts in my mind that I could really make it,” he said in accepting the Fordham Founder’s Award in 2014. “But with Fordham’s incredible spirit and culture, they instilled into me a confidence and an education that truly transformed me.”

Professors took a personal interest in him, encouraging him to attend graduate school, he said in an interview. After graduating from Fordham’s College of Pharmacy (which has since closed) in 1961, he earned a doctorate in medicinal chemistry from the University of Washington and went to work at Dow Chemical as a research chemist. He retired from the company 39 years later—as chairman and CEO. He won several awards along the way, including one from the Society of the Chemical Industry recognizing the high ethical standards be brought to that industry.

Through their family foundation, he and Linda Stavropoulos have supported a range of efforts in health care, human services, and higher education—including Fordham’s Orthodox Christian Studies Center, in part because of its efforts to help bridge a centuries-old divide.

Healing a Schism

Christianity split into the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches nearly a millennium ago, in 1054, due to religious disputes and political conflicts. There have been many steps toward rapprochement between the estranged eastern and western churches—in 1964, Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras and Pope Paul VI met in the Holy Land for joint prayer, the first time the two churches’ leaders had met in more than 500 years. A year later, they agreed to revoke the churches’ mutual excommunication decrees dating from 1054.

In 2014, Pope Francis and Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew met for a service in Jerusalem to celebrate the meeting’s 50th anniversary; in a homily, the latter called for shedding “fear of the other, fear of the different, fear of the adherent of another faith, another religion, or another confession.”

Among the attendees were William and Linda Stavropoulos, who went with a group organized by the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. “It was very moving, and encouraging, that the symbolism of that [meeting]could expand to something on a more tangible, everyday basis,” Linda Stavropoulos said.

The Orthodox Christian Studies Center promotes this cause through scholarship and events such as the Patterson Triennial Conference on Christian Unity. “I think these are times where we need that unity,” William Stavropoulos said. “It seems like we’re having polarization like I’ve never seen before in my lifetime, and I think this is one area where maybe we can get together. I think we’re better united than divided.”

As members of the Greek Orthodox church, he said, he and Linda Stavropoulos have “a natural affinity” for the Orthodox Christian Studies Center and believe in the work it’s doing. In 2014, they made a gift to help the center secure a National Endowment for the Humanities challenge grant in support of dissertation fellowships.

Fueling the Growth

This will be the first dedicated physical space the center has ever had, Demacopoulos said. Its large common area will enable informal gatherings by students who are pursuing the Orthodox Christian studies minor or who belong to the Fordham chapter of the Orthodox Christian Fellowship, a nationwide student organization.

Over the past several years, the center has fueled interest in Orthodox Christian studies, drawing students from as far away as California and Eastern Europe, he said. He expects the new facility to amplify this interest and draw more students to the Orthodox Christian studies minor—and not just Orthodox Christians, but also those from outside the tradition who want a better understanding of it.

“The center is not just theology; it’s the whole history, thought, and culture of the Orthodox Christian world, broadly understood,” Demacopoulos said.

By generating new interest in the Orthodox Christian Studies Center, the facility could prompt more faculty members to develop courses that fit the minor and create more opportunities for students to understand Orthodoxy across disciplines, he said.

“It’s going to lead students to see these connections in their other classes—when they’re taking their international business classes, when they’re taking their political science classes, when they’re taking their religion classes, when they’re taking their history classes,” he said. “It’s going to be a much more holistic academic experience for them.”

The new facility is a key priority of the center’s current $5 million 10th Anniversary Campaign: Engaging Orthodoxy, along with creating a research endowment for Orthodox Christian studies at Fordham.

To inquire about supporting the Orthodox Christian Studies Center or another area of the University, please contact Michael Boyd, senior associate vice president for development and university relations, at 212-636-6525 or [email protected]. Learn more about Cura Personalis | For Every Fordham Student, a campaign to reinvest in every aspect of the Fordham student experience.

]]>Cohen’s legacy includes launching and leading four pharmaceutical companies and testifying before Congress to expose corruption in the Food and Drug Administration. Most recently, he served as the founding CEO and chairman of Summit BioSciences Inc., a Lexington, Kentucky-based pharmaceutical company that develops and manufactures nasal spray medicines.

“[He] was an advocate for Fordham University since graduating from the College of Pharmacy, and always credited the experience and education he received at Fordham as the building block for his future business endeavors,” Cohen’s son Richard wrote in an email.

Although Fordham’s College of Pharmacy closed in 1972, Cohen remained close to his alma mater, particularly the Gabelli School of Business. After serving on the University’s Board of Trustees from 2000 to 2004, he became a trustee fellow. He and his wife, Nadia, have also been generous benefactors of Fordham, supporting scholarship funds for students and research at the Graduate School of Social Service’s Ravazzin Center on Aging and Intergenerational Studies, among other initiatives.

In 1997, Fordham awarded Cohen an honorary Doctor of Science degree during the University’s annual commencement ceremony. Sharon Smith, Ph.D., then dean of the University’s undergraduate business school, read the citation.

“One of the enduring challenges facing American society is the development of a system of health care that is both medically and economically sound and responds to the needs of all of our citizens,” Smith said. “Mr. Cohen’s success in providing generic drugs to the public has set a standard for other business leaders to emulate.”

To that end, Cohen made a significant impact on the global pharmaceutical industry. He worked with the U.S. Agency for International Development and Egypt’s Ministry of Health to expand the use and availability of generic drugs, and was invited to Turkey and Mexico to work with industry leaders on maximizing pharmaceutical exports to reach new territories.

Under his leadership, Summit BioSciences achieved annual sales between $1 million and $5 million and expanded its facilities and staff by nearly triple since he founded the company in 2008. In the late 1990s, Cohen founded Intranasal Therapeutics, now known as Ikano Therapeutics, and served as the company’s CEO and chairman. He made his first foray in the industry in 1959, when he co-founded Davis-Edwards Pharmacal Corporation, which became one of the first companies to manufacture and promote multisource drugs.

Another milestone in Cohen’s career was his leadership of Barr Laboratories Inc., a pharmaceutical company he launched in 1970 that traded on the New York Stock Exchange and grew to more than $3 billion in annual sales before the company was acquired by Teva for $7.5 billion in 2008. During his tenure, Forbes magazine named him among the 200 Best Small Companies’ Chief Executives. As CEO of the firm, Cohen testified before Congress to expose several corrupt officials at the FDA who were later found guilty of taking bribes and manipulating the drug approval process.

Cohen was a founding member of the Generic Pharmaceutical Industry Association (the predecessor to the Association for Accessible Medicines) and a founding member and executive board member of the National Association of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers. He also served as chairman of New Concepts for Living, an organization that provides support for people living with developmental disabilities.

After he graduated from Fordham, Cohen earned an M.B.A. from the City College of New York and completed a program in organizational change and marketing management at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business. He enjoyed traveling with his wife and had a keen interest in New York City architecture and World War II history.

He is survived by his wife, Nadia; daughter, Andrea Cohen-Lenihan; and three sons, Richard, Steven, and Michael.

—Claire Curry

]]>

The action on Coffey Field didn’t yield a “W” in the score column on Sept. 22, but that didn’t diminish the enthusiasm of more than 5,000 alumni, students, family, and friends who flocked to Fordham’s Rose Hill campus for the annual Homecoming celebration.

Before the faceoff between the Rams and Central Connecticut State University’s Blue Devils got underway, the campus was abuzz with activity. Runners took in views of the campus in the seventh annual 5K Ram Run, while members of the oldest club in the University, the Mimes and Mummers, shared memories in Collins Auditorium. As some families laid out lavish tailgating spreads in the parking lot, others gathered in the big tent for burgers and all the fixings. There was even a walking tour of all things Jesuit-related by former Fordham Law School Assistant Dean Robert J. Reilly, FCRH ’72, LAW ’75.

In the parking lot, Fordham College at Rose Hill senior Hayley DeWeese sat surrounded by her extended family and trays of homemade food. The physics major said she loved being there with the large group, including her cousin Emma DeWeese, FCRH ’10. The pair was excited that Emma would be presenting Haylee with her diploma at commencement this May.

Emma’s mom, Joanne DeWeese, said they’ve been tailgating at Homecoming for years.

“It’s such great family time, especially when our niece decided to come here. Then we knew we could extend our tailgate family weekends,” she said.

This year the family also had some friendly rivalry to contend with. Haley’s dad, Cory DeWeese, brought his nephews, who are students at Central Connecticut State. Their father, Mo Harmon, was decked out in a Fordham hat and a Central t-shirt. “I’m supporting both teams,” he said, smiling.

Representing the 1968 Football Club

Photo by Patrick Verel

In the loyal donor appreciation tent, Jack McMahon, FCRH ’71, a cornerback for the 1968 national club football championship team, flew in from Okinawa, Japan, for the day. It was the second time he’d made that 24-hour journey. He and 31 other members of the team were welcomed back onto the field during the game for a ceremony honoring their accomplishment.

“We were club football, which meant you played, worked, and practiced because you loved it,” he said, noting that that team consistently outplayed their opponents in the fourth quarter because they put in that extra time and effort.

“Military people understand that when you’re in the service, you’re not fighting for your country and your flag, you’re fighting for the guy next to you. It’s a similar concept,” he said, adding that being back on campus reminded him of that spirit.

“You come back and see people who practiced as hard as you did, who worked as hard as you did, and were successful because of it. That just means a lot.”

Blue and Maroon Balloons

Blue and Maroon Balloons

Nearby, Jean Wynn, MC ’80, sported a blue Marymount shirt while chatting with her daughter, Amanda Shea, a junior in the Gabelli School of Business.

Wynn said Fordham was “very welcoming” after it merged with Marymount and eventually sold the college. She encouraged her fellow Marymount grads to come to Homecoming— “That’s what those big blue balloons are all about,” she said, pointing to the big tent and noting she’d seen about 10 Marymount alumnae so far. The event is even nicer for her now, she said, that her daughter attends Fordham.

Shea, a finance major, agreed.

“I get to get into all the tents!” she said, laughing.

‘Our Happy Place’

As children scaled an inflatable climbing wall and played cornhole at the foot of Keating Hall, Mike Brady, GABELLI ’06, ’12, and Katelyn Brady, FCRH ’06, took in the scene with their 1-year-old son Jack. The couple met when they were students, but only started dating after graduation. Four years ago, he convinced her to attend a presentation for a summer class he was taking at the time. Little did she know, he was also carrying an engagement ring.

“He had a fake presentation and everything that he was showing me on train. We were walking up the steps into Keating, and he stopped and turned to me, and I was like, ‘Oh my god.’ I was shocked,” she said.

“We love it here. This is our happy place.”

Lessons from the Past

Contributed photo

In the main tent, Pascal Storino Jr., GABELLI ’84, was relaxing with his family before heading to section F of Coffey Field, where they hold season tickets. Their connection to the University encompasses three generations—his father Pascal Storino, PHA’59; his wife Thalia Julius-Storino, GABELLI 85, 91; and their daughters Angelica Storino, FCRH’19, and Christina Storino, FCRH’17, GSE’18.

Inspired by the flair of a fellow fan, Storino Jr.was sporting an early-1940s- era pin that was popular with the Fordham football team at the time. Since it was distributed shortly before the program was paused in 1943, the pin depicted a World War I-era tank, instead of a traditional football. An avid fan of history, he noted that his grandfather shoveled coal into furnaces upon his return from World War I.

“When my girls came here, I reminded them to be respectful, and that the people they need to be nicest to are the people who influence their lives on a daily basis, like the people who clean the dorms and the people who work here,” he said.

“When my girls came here, I reminded them to be respectful, and that the people they need to be nicest to are the people who influence their lives on a daily basis, like the people who clean the dorms and the people who work here,” he said.

Andrew Bournos, GABELLI ’92, and Danielle Dexter, FCRH ’93, made the pilgrimage from New Fairfield with four of their five children: Cassandra, 14, Gordon, 12, Vivienne, 10 and Brock, 5. They met at homecoming Danielle’s first year, but didn’t reconnect for another three years. They wed at the University Church 20 years ago.

“My uncle told me before I went, ‘What separates the men from the boys is, the boys know how to party, the men know how to party and study. Go be a man.’ I wasn’t the first six months, but it finally hit me, so I got both done,” he said, laughing.

For teenaged Cassandra, the experience of attending has changed since the family first started coming regularly seven years ago; the bouncy castle no longer holds the same appeal. But she still enjoys the day.

“I’ve always loved the face painting and the sketches that they do and climbing the big inflatable wall,” she said. “It’s still a lot of fun.”

—Nicole LaRosa contributed reporting

Video by Taylor Ha and Miguel Gallardo

]]>A child survivor of the Holocaust was reluctant to share his family’s full story, until he saw a picture of himself as a 4-year-old boy at Auschwitz on a website denying the Holocaust

For years, Michael Bornstein, PHA ’62, wished he could wash away the serial number—B-1148—that was seared into his left forearm when he was just 4 years old. He’d mention Auschwitz, if asked about the tattoo, but he wouldn’t dwell on the Nazi death camp where his father, brother, and nearly 1 million other Jews were murdered during World War II. He’d seldom speak of being separated from his mother, who withstood beatings from female guards as she smuggled bread and thin gray soup to him in the children’s barracks, and who later smuggled him into the women’s barracks before she was sent to a labor camp in Austria. He wouldn’t say much about how his grandmother somehow, improbably, kept him alive long enough for them to be among the 2,819 prisoners liberated by Soviet soldiers.

His recollection of those dark days is dim—“a blessing and a curse,” he says. He seems to recall the stench of bodies burning, the smoke rising from crematoria chimneys, the quickening clack of guards’ boots. But he’s also aware of the malleable nature of memory, how the things we recall, especially from early childhood, are shaped by some inscrutable mix of perception, imagination, and the stories we’re told. And so for years he stayed mostly silent about his past, not only because it was traumatic but also because so much of it—the texture of his brother’s hair, the sound of his father’s voice—was inaccessible to him.

He preferred to look forward, with an optimism he says he inherited from his mother. Gam zeh ya’avor, she’d tell him, quoting the motto she and her husband shared during the war. This too shall pass. He can still hear the sound of his mother’s voice because she found him in Żarki, Poland, after the war. In February 1951, when he was 10, they immigrated to the United States, where he’d go on to build a career in pharmaceutical research and—with his wife, Judy—raise four children in what he calls “a life filled with soccer games, birthday parties, and bliss.”

As his kids grew up, they began pressing him for details about his past, but he’d always resist a full recounting. Now Bornstein is 77, and his children have children of their own. Several years ago, when Jake Wolf, the eldest of his 11 grandkids, started asking questions, wanting to use the information for his bar mitzvah project, Bornstein couldn’t say no. He began to open up.

Then he saw something that left him stunned and more determined than ever to tell his story: a picture of himself as a boy at Auschwitz on a website claiming that the Holocaust is a lie, that it never happened. “I slammed my computer shut in disgust. I was horrified. My hands shook with anger,” he writes in Survivors Club: The True Story of a Very Young Prisoner of Auschwitz, published last March by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. “But now I’m almost grateful for the sighting. It made me realize that if we survivors remain silent—if we don’t gather the resolve to share our stories—then the only voices left to hear will be those of the liars and bigots.”

Bornstein wrote the book with his daughter Debbie Bornstein Holinstat, a TV news producer who for years had urged her father to work on such a project. She helped him plumb his earliest, darkest memories, and together they searched historical records and interviewed relatives and others who knew his family in Poland. In the process, they discovered a detail that helped solve one of the biggest mysteries of his survival, and he learned much about the resolute, resourceful father he never got to know. Together, they reclaimed a family heritage, illuminating stories of loss and resilience that had been left largely untold for 70 years.

Żarki, Open Ghetto

Michael Bornstein was born on May 2, 1940, in the Nazi-occupied town of Żarki, Poland, the second son of Sophie Jonisch Bornstein and Israel Bornstein, baby brother to 4-year-old Samuel. They lived in a redbrick house on Sosnawa Street.

In some parts of Poland during the late 1930s, Jews couldn’t own land, and their business dealings were restricted. But Jewish-owned businesses thrived in Żarki, where more than half of the town’s population, approximately 3,400 residents, was Jewish. Bornstein’s father was an accountant, and his mother’s brother Sam Jonisch (one of her six siblings) ran his family’s leather tannery in town.

That changed on Friday, September 1, 1939, when German forces invaded Poland, reaching Żarki the following day with an aerial attack that torched some homes and businesses. Sophie, newly pregnant with Michael, wanted to check on her parents, who lived nearby. But Nazi storm troopers had already moved onto the streets. On Monday, when all Jewish men in Żarki were ordered to report for labor shifts, Sophie left Samuel with her mother-in-law, Dora, and set out to find her parents. As she neared the Jewish cemetery, she saw German soldiers command a family she recognized from synagogue to strip naked. As mother, father, and young daughter huddled together, the soldier fired three shots, and the family fell dead in the ditch the father had just dug. It was a scene that haunted Sophie Bornstein her entire life.

The Nazis murdered more than 1,000 Jews in Poland that day, including 100 in Żarki. Such atrocities brought out the worst in some gentile residents, Bornstein and Holinstat write. “Many Catholics had not liked living among Jews before the war. Now they blamed the town’s Jewish people for making them the target of German bombings.”

In October, as Nazi soldiers went door-to-door confiscating Jews’ money and jewelry, Israel Bornstein sought to safeguard his family’s valuables. He gathered what he could in a burlap sack—a string of pearls, a stash of banknotes, the family’s small silver kiddush cup—and buried it in the backyard.

Żarki was still an open ghetto at the time, which meant that it wasn’t surrounded by fences, but Jews couldn’t come and go as they pleased. The Nazis shut down or took over Jewish businesses, enforced a strict curfew, and made Jews wear white armbands with a blue Star of David on them. They also forced them to create a Judenrat, a council of Jewish leaders. The town elders elected Israel Bornstein to serve as president. It was not a coveted role. Many Jews in Eastern Europe came to see Judenrat members as traitors, simply doing the bidding of the Nazis, and in Żarki people viewed Israel with suspicion.

But in their research, Bornstein and Holinstat found a collection of essays and a detailed diary written in Hebrew that told of Israel Bornstein’s heroic, often successful efforts to make conditions more bearable. In Survivors Club, they describe how he collected money from fellow Judenrat members and used the funds to bribe Gestapo officers, helping to obtain 200 legal travel visas for families trying to leave Żarki, for example, and saving the life of a teenager who faced execution because he was too sick to work one day.

“Though it’s sometimes seen as a very negative position, my father used it to save people. He set up soup kitchens. He was a very good man. And it made a lot of difference to me knowing that he was a good man,” Bornstein says. “That’s one reason we called the book ‘Survivors Club,’ because my mother’s six siblings all survived, and part of it has to do with my father, who encouraged them to go into attics, basements, wherever they could go to survive.”

By October 1942, however, the call had come for Żarki to be made Judenrein, “clean of Jews.” Most of those remaining were sent by train either to labor camps or to extermination camps. The Bornsteins and approximately 120 others were allowed to stay behind as part of a cleanup crew, but eventually they too were sent away, to a labor camp in Pionki. And in July 1944, when that camp closed, they were packed onto trains bound for Auschwitz.

“Sickness Saved My Life”

Upon arrival at Auschwitz, like all families, they were split up: Israel and Samuel were assigned to the men’s side. Michael initially stayed with his mother and grandmother until guards shaved his head and tattooed his arm. He was sent to the children’s barracks, where some older kids looked out for him, warning him to hold his nose as he drank down the smelly gray soup. Other kids stole his bread. Sophie was sent to the women’s barracks with Michael’s grandma Dora. She risked her own well-being to find her son and eventually bring him into the women’s barracks, where he hid under straw, in corners, scattering at the sound of guards approaching to take roll call.

While Sophie was able to protect Michael, she was helpless to save her husband and young Samuel, who died in September from the effects of Zyklon B gas—the Nazis’ preferred method of execution at Auschwitz, where as many as 6,000 people per day were killed in gas chambers. “[My mother] later told me that her heart literally felt like it had been gouged from her chest with an ax” when she learned of their fate, Bornstein writes. Soon, however, she was sent to a labor camp in Austria, and Michael was left alone with his grandma Dora.

By January 1945, with Soviet forces closing in on Auschwitz, the Nazis started to evacuate the camp, forcing an estimated 60,000 prisoners on what came to be known as a death march to concentration camps in Germany. Many prisoners, already frail from malnutrition, died from exposure in the harsh winter. But Michael and Dora evaded the march, and Bornstein always wondered how.

Not long ago, while visiting Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial museum in Israel, he discovered a document that solved the mystery. Nazi records indicate that he was in the infirmary at the time, diagnosed with either diphtheria or dystrophy (the writing is unclear). And his grandmother was with him. “The name doesn’t really matter,” he writes in Survivors Club. “That piece of paper recovered by a museum years after the war made one miracle clear. Sickness saved my life.”

On January 27, nine days after he found refuge in the infirmary, Soviet troops arrived. A couple of days after liberation, Dora carried Michael out to freedom, a scene captured on film by Soviet cameras. “Of the hundreds of thousands of children who had been delivered by train to Auschwitz, only 52 under the age of eight survived. They were the world’s best hiders,” Bornstein writes. “I was one of them.”

Postwar Dangers and the Cup of Life

Bornstein’s freedom brought with it a new set of dangers. “I would like to tell you … that all of us went home and lived happily ever after,” he writes. “But it wasn’t like that at all.” Four out of 10 Jews who survived the concentration camps died within a few weeks of the arrival of the Allied armies. Those who did survive found much of Eastern Europe unsafe for them, particularly in Poland, where anti-Jewish sentiments led to a series of murderous pogroms.

Soon after liberation, Michael and Dora returned to Żarki, where they found the family home on Sosnawa Street had been seized by a Polish family who now saw it as their home. Dora took Michael to a farm on the edge of town, where they found shelter in a chicken coop. They would periodically head into what had been the Jewish quarter, where they met relatives who were, miraculously, among the few dozen Jews (out of 3,400 six years earlier) to return to Żarki after the war. One day, as Michael and Dora walked in town, he spotted his mother, who had made her way back from Austria. “If we had both seen more horror than the world knew it could hold—then this moment was the opposite of that,” he writes. “This was the opposite of despair.”

Sophie realized that there was little opportunity left for them in Żarki. But first she tried to recover the valuables her husband had buried. “At night, even though the house was occupied, she went digging with her bare hands to try to find these things, jewels and money, and the only thing that she found was the kiddush cup, which is a cup that you make blessings with,” Bornstein says.

“And so this cup has been in our family ever since. It’s been at my wedding, at our kids’ weddings, at their bar mitzvahs, bat mitzvahs, and so on. It’s not worth much if you buy it for the silver, but we cherish it quite a bit.”

In Munich, Waiting on Passage to America

After the war, Dora decided to remain in Poland, but Sophie determined that she and Michael would apply for visas to the United States. “She said the word ‘America’ the way a child says the word ‘candy,’” Bornstein writes. “She told me America was the most wonderful and welcoming place you can imagine.” That was not the case for them in Żarki or in Munich, where the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society assigned them to a displaced persons camp and, later, to a one-room apartment in the city.

“The German kids were bullies,” Bornstein recalls. “I had no hair on my head, I was skinny, and I didn’t speak the language, so I was bullied quite a bit.” Sophie bought flour and nylons from American soldiers and sailors in Munich, and sold the goods on the black market. It was a risky way to make a living, and Bornstein feared that she’d be arrested and he’d lose his mother again. But after nearly six years, they received their visas and set off on the USS General M. B. Stewart, arriving in New York City in February 1951.

With help from aid organizations, they eventually settled in a small apartment on 98th Street and Madison Avenue. Sophie worked as a seamstress, making $30 a week, and Michael attended P.S. 6. “I was this little kid who didn’t speak much English and had a tattoo on his arm. The teachers didn’t say anything, so I was pretty much alone and didn’t have friends,” recalls Bornstein, who soon found a job that would prove to be consequential. “I worked at Feldman’s Pharmacy, at 96th and Madison, getting 50 cents an hour,” he says. “The head pharmacist, Victor Oliver, was very good to me. He kind of took me on as a father figure and sparked my interest in science.”

Oliver even attended Bornstein’s bar mitzvah, held at Park Avenue Synagogue, after which his mother gave him a gift that she’d been saving for years to buy him: a gold watch. “You have to wind it a few times a day to make it work, but it’s great,” he says. “And on the back, it has a gimel and a zayin, which are the Hebrew letters for gam zeh ya’avor, ‘This too shall pass.’”

“A Can-Do, Get-It-Done Type of Guy”

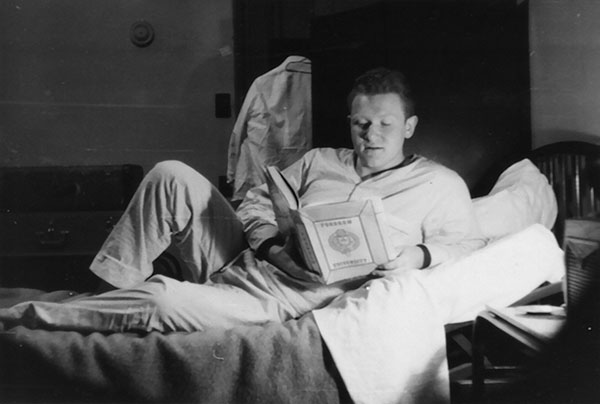

Bornstein’s mother also instilled in him a deep appreciation for the value of education. Like faith, she’d tell him, education can’t be taken away. In 1958, he enrolled at Fordham’s College of Pharmacy, just as she embarked on a new chapter in her life. “My mother remarried and moved to Cuba because her sister was there,” he says. She would later return to the States and settle in South Florida, but at the time, Bornstein says, “I was pretty much homeless, and Fordham didn’t have any room in the dormitories, so they put me up in the infirmary.” It was the second time in his life that an infirmary saved him, he says. “I would probably have skipped college if it weren’t for that.”

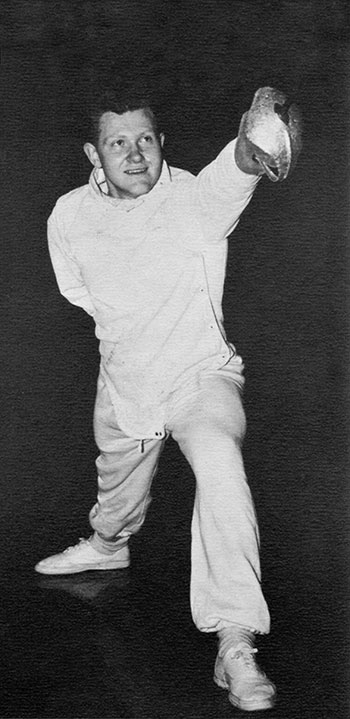

In addition to providing Bornstein with room and board, Fordham gave him a partial scholarship. He spent summers working in the Catskills to help pay any remaining tuition costs. “I was a chamber maid, then a busboy, then a waiter, and finally a head waiter,” he recalls. “The salary was only about twelve dollars a month, but the tips made it.” On campus, he found a niche on the fencing team.

One of his former Fordham classmates, William Stavropoulos, PHA ’61, recalls Bornstein as a “nice, friendly guy.” He says he and his friends in G House at Martyrs’ Court never would have suspected the horrors Bornstein had been through. “I remember distinctly sitting around one day and a guy asked Mike about his tattoo. He mentioned the camp and said his mother used to hide him here and there, keep him out of sight of the guards, but he didn’t say much else. He was always upbeat.”

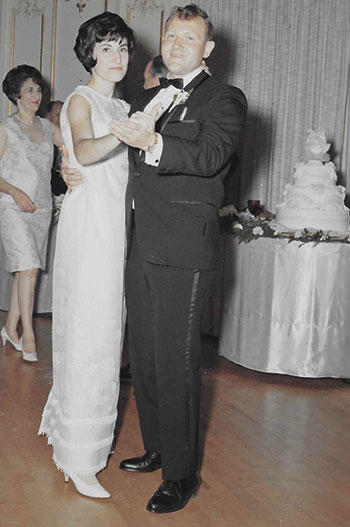

After graduation, Bornstein enrolled at the University of Iowa, where he earned a Ph.D. in pharmaceutics and analytical chemistry. But he says his greatest achievement there was meeting an undergraduate named Judy Cohan. “We obviously hit it off. He had the same interests I did, and he was persistent,” recalls Judy, who was studying special education. They attended movies and plays, and he accompanied her on visits to the children’s ward at local hospitals. “He was very caring of the children, and that was important to me.”

They were married nearly 50 years ago, on July 9, 1967, after Bornstein began his career at Dow Chemical in Zionsville, Indiana. While there, he reconnected with Stavropoulos, who had earned a Ph.D. in medicinal chemistry at the University of Washington and would go on to become chairman and CEO of Dow. The two, both newlyweds at the time, would see each other socially, and Stavropoulos even helped the Bornsteins move into their new apartment. But they lost touch over the years. “He went to work for Eli Lilly, and I stayed at Dow,” Stavropoulos recalls. In the late 1980s, Bornstein and his family moved to New Jersey, where he worked as a research manager for Johnson & Johnson, eventually rising to director of technical operations, a position that took him to Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, France, and elsewhere.

“He was a streetwise guy, and I always knew he was going to be a success,” Stavropoulos says. “When I think of Mike, I think of a positive, can-do, get-it-done type of guy. At Dow he was that way, and at Fordham too. It’s an incredible story. He’s obviously a courageous man.”

Fighting Intolerance with Compassion

Holinstat says her dad’s courage was especially evident during the process of writing the book. “My father is such a positive man, and he’s gone out of his way his entire life to show his kids and his grandkids nothing but positivity, so for him to dig deep and be willing to open up and talk to me about the deepest, darkest places in his memory was difficult for him, and it was hard for me because I knew how hard it was for him.” But the process has been well worth it, she says, explaining that they wrote Survivors Club with readers as young as 10 years old in mind.

“For my dad, a big piece of this was making sure that his grandkids understood the atrocities of the Holocaust. So it was really important to us to write something that the kids could grasp at this stage in their lives, and that they could share with their peers, because this next generation, most of them will grow up not having met a Holocaust survivor.”

In March, shortly after the book was published, it became a New York Times best-seller. The paper’s reviewer noted that the book combines the “emotional resolve of a memoir with the rhythm of a novel,” and that, although the book is marketed for young readers, “the equal measures of hope and hardship in its pages lend appeal to an audience of all ages.”

Holinstat waited decades for the opportunity to help her father tell his story, but she feels the timing of the book’s publication could not be more poignant or pointed, coming amid a recent surge in anti-immigrant and anti-Semitic sentiments in the U.S. “I truly believe that this story is being released now for a reason, to remind people what happens when bigotry goes unanswered,” she says.

The core moral lesson of the Holocaust, she and her father believe, is the ease with which any group of people can be dehumanized. “The world can never forget what happens when discrimination is ignored,” Bornstein said last April at Congregation Beth-El Zedeck in Indianapolis. “And it’s not just discrimination against Jewish people but against all minorities, and that includes Muslims, Mexicans, and African Americans. It’s time for compassion; it’s time for empathy.”

Bornstein plans to return to Poland this year with Judy, their children, and other family members. Holinstat has been communicating with people in Poland about establishing a Holocaust memorial in Żarki, and the family will be going to Auschwitz, which Bornstein visited in 2001 with Judy and in 2010 with his son, Scott.

In the meantime, Jake Wolf, the grandson who persuaded Bornstein to share his story, is preparing for his freshman year at Syracuse University, where he intends to major in both communications and business. “In our family,” he says, “it’s so important to know how difficult it was for my grandpa. He never had any hate toward the world for what he was put through. And that inspires all of us. If he could get through that with a smile on his face, we can do anything.”

A “Survivors Club” Reunion in the Suburbs

Since the publication of the book, Bornstein has heard from many people who have thanked him for telling his story, including some who understand all too well what he and his family endured. Sarah Ludwig was the 4-year-old girl standing next to Bornstein in the iconic photo from Auschwitz. Tova Friedman, then 6, stood just behind Ludwig as the children showed their tattoos to Soviet soldiers. The three survivors recently learned that they live just miles from each other in suburban New Jersey.

On Sunday, June 4, they gathered with kids, grandkids, and other relatives for a reunion brunch at Holinstat’s home that included prayers of remembrance and celebration, and the use of one precious silver cup. For Holinstat, it was a remarkable coda to the experience of helping her father tell his story after all these years.

“The last time they saw each other, they were kids wearing prisoners’ stripes,” she says. “Now they’re surrounded by family.”

—Ryan Stellabotte is the editor of this magazine.

Watch NBC Nightly News‘ coverage of the reunion.

]]>