A Bridge to Justice: The Life of Franklin H. Williams

People tend to view 20th-century civil rights heroes through a “sepia lens,” Sherrilyn Ifill, former head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, once said. But those leaders were not “superpeople deposited from some other planet.” They were “ordinary people of extraordinary intellect” and courage who still have the power to show us how to create “a true democracy.” Ifill was speaking at a 2018 Fordham Law School event celebrating the legacy of civil rights attorney and diplomat Franklin H. Williams, LAW ’45.

People tend to view 20th-century civil rights heroes through a “sepia lens,” Sherrilyn Ifill, former head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, once said. But those leaders were not “superpeople deposited from some other planet.” They were “ordinary people of extraordinary intellect” and courage who still have the power to show us how to create “a true democracy.” Ifill was speaking at a 2018 Fordham Law School event celebrating the legacy of civil rights attorney and diplomat Franklin H. Williams, LAW ’45.

In A Bridge to Justice, Enid Gort and John M. Caher recount Williams’ “profound impact on the (still unfinished) struggle for equal rights.” Born in New York City in 1917, he attended Lincoln University, the nation’s first degree-granting historically Black university, before enrolling at Fordham Law School in 1941. Service in the segregated U.S. Army interrupted his legal studies and “scarred Williams,” the authors write, but he earned his law degree in 1945 and soon joined the NAACP.

For the next 14 years, he worked on seminal civil liberties cases that overturned racially restrictive housing covenants and school segregation. And he often put his life on the line, once barely escaping a lynch mob in Florida, where he defended three Black youths falsely accused of rape. He went on to help organize the Peace Corps; serve as ambassador to Ghana; lead a nonprofit dedicated to advancing educational opportunity for Africans, African Americans, and Native Americans; and chair a New York state judicial commission, now named in his honor, that works to promote racial and ethnic fairness in the courts. Williams died in 1990, but his life story, the authors write, “is an object lesson for those with the courage and fortitude to … help this nation heal and advance through unity rather than tribalism.”

Cross Bronx: A Writing Life

“The most important thing human beings have, the thing that makes us human, are stories,” Peter Quinn, GSAS ’75, told this magazine in 2017. For more than four decades, the Bronx native has been a remarkably accomplished storyteller—as a novelist, chief speechwriter for New York Governor Mario Cuomo, and witty, humane chronicler of New York City and the Irish American experience. In the past two years, Fordham University Press has reissued four of his novels, including Banished Children of Eve: A Novel of Civil War New York, which earned Quinn a 1995 American Book Award; and an essay collection, Looking for Jimmy: A Search for Irish America (2007). Now comes this delightfully funny and frank memoir of his Catholic upbringing, his enduring affinity for his native borough (“I don’t live in the Bronx anymore, but I’ll never leave”), and the circuitous, consequential path of his writing life. His journey took him from Fordham grad student to chief speechwriter for two New York governors and corporate scribe for “five successive chairmen of the shapeshifting, ever-inflating, now-imploded Time Inc./Time Warner/AOL Time Warner,” a chapter of his memoir he cheekily calls “Killing Time.” He also writes of meeting and courting his wife, Kathy, of the “intense joy and satisfaction of fatherhood,” and of coming to terms with his own emotionally distant father. “Looking back, what I’m struck by most is luck,” he writes. “What I feel most is gratitude.”

“The most important thing human beings have, the thing that makes us human, are stories,” Peter Quinn, GSAS ’75, told this magazine in 2017. For more than four decades, the Bronx native has been a remarkably accomplished storyteller—as a novelist, chief speechwriter for New York Governor Mario Cuomo, and witty, humane chronicler of New York City and the Irish American experience. In the past two years, Fordham University Press has reissued four of his novels, including Banished Children of Eve: A Novel of Civil War New York, which earned Quinn a 1995 American Book Award; and an essay collection, Looking for Jimmy: A Search for Irish America (2007). Now comes this delightfully funny and frank memoir of his Catholic upbringing, his enduring affinity for his native borough (“I don’t live in the Bronx anymore, but I’ll never leave”), and the circuitous, consequential path of his writing life. His journey took him from Fordham grad student to chief speechwriter for two New York governors and corporate scribe for “five successive chairmen of the shapeshifting, ever-inflating, now-imploded Time Inc./Time Warner/AOL Time Warner,” a chapter of his memoir he cheekily calls “Killing Time.” He also writes of meeting and courting his wife, Kathy, of the “intense joy and satisfaction of fatherhood,” and of coming to terms with his own emotionally distant father. “Looking back, what I’m struck by most is luck,” he writes. “What I feel most is gratitude.”

South Bronx Rising: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of an American City

For nearly 40 years, Jill Jonnes has been among the most persistent chroniclers of the Bronx, giving eloquent voice to the citizen activists who have driven its revival. In 1986, when she published the first edition of South Bronx Rising, Bronxites were just beginning to reverse the toxic effects of long-term disinvestment. “Today,” she writes in the third edition of the book, “we far better understand the interplay of blatantly racist government policies and private business decisions … that played a decisive role in almost destroying [Bronx] neighborhoods.”

For nearly 40 years, Jill Jonnes has been among the most persistent chroniclers of the Bronx, giving eloquent voice to the citizen activists who have driven its revival. In 1986, when she published the first edition of South Bronx Rising, Bronxites were just beginning to reverse the toxic effects of long-term disinvestment. “Today,” she writes in the third edition of the book, “we far better understand the interplay of blatantly racist government policies and private business decisions … that played a decisive role in almost destroying [Bronx] neighborhoods.”

The revival began with “local activists and the social justice Catholics … mobilizing to challenge and upend a system that rewarded destruction rather than investment.” Countless Fordham students, faculty, and alumni have contributed to this movement, helping to establish and sustain groups including the Bronx River Alliance and the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition. It’s not all roses: The South Bronx remains part of the country’s poorest urban congressional district; the “calamity of COVID” hit communities hard; and gentrification threatens to undo hard-fought progress. But Jonnes provides ample reason to celebrate and continue the work.

]]>In a lecture on Oct. 19, a leading scholar of education and law warned that allowing parents to choose to send their students to charter schools that operate without sufficient oversight will actually threaten the student’s civil rights.

“I’ve heard people make arguments about the real need for school choice,” said Preston Green III, Ed.D. He acknowledged that charter schools—a key element of school choice—can provide needed opportunities for families, but said that local governments must regulate them.

“Certainly, communities of color have said that many of them do support school choice programs, because they feel that it meets a need. If there is that need, then we can meet it, but we cannot then step aside and then say that they cannot be regulated. There have to be protections in place for communities, for students, and for school districts.”

Green, the John and Maria Neag Professor of Urban Education at the University of Connecticut, delivered his remarks as part of the Graduate Schools of Education’s annual Barbara L. Jackson, Ed.D., lecture.

An Expanding Role in Education

He began by acknowledging that charter schools, which are not subject to all the rules and regulations of local education departments, but are funded by taxpayer funds, are not only a fundamental part of the landscape, but are expanding.

In the United States, there are 7,500 charter schools in 45 states and the District of Columbia, serving 3.4 million students. Although the rules governing the schools vary widely across the country, there are three general areas where many of them fall short, he said.

They are the loss of civil rights, increased stress to fiscally strapped districts, and predatory contracts.

When it comes to civil rights, Green said, marginalized groups should remember one thing: “They can’t keep you out, and they can’t drum you out,” he said.

Families should know, he said, that they are protected by federal statutes that all schools, be they public, charter, or private, must follow. They include Title VI, which prohibits discrimination against a person based on their race, ethnicity, of national origin; Title IX, which protects against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity; the Equal Educational Opportunities Act, which protects English Language Learners; and the Individuals with Disabilities Act and Section 504, with both protect students with disabilities.

A Key Protection That Needs Attention

To those, Green added the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. 14th Amendment, and the Due Process Clause, which provides a student who may be suspended or expelled the right to be alerted to the charges and given an opportunity to plead their case. Although charter schools fulfill the first five, Green said it’s an open question whether they fulfill these last two, as public schools do.

As an example, he cited Peltier v. Charter Day School, an ongoing case in North Carolina that has received split rulings in federal court and may be resolved by the U.S. Supreme Court. The school has a strict dress code that says girls must wear skirts and boys must wear pants, a provision that Green said would be a clear violation of the equal protection clause because it discriminates on the basis of sex. The school argued that it is not legally a “state actor,” though, and should be exempted from the clause in the same way that private schools are.

This has major implications for Black students, he said, because some schools have policies forbidding Afrocentric hair. The good news is, he said, is that there are 27 states that prohibit charter schools from violating students’ equal protection rights.

“I would argue that all states need to adopt this type of language to ensure that the civil rights of students are provided for,” he said.

Addressing the Financial Impact of Charters

When it comes to increased stress to fiscally strapped districts, Green made the case that both urban and rural school districts often suffer financially when charter schools are established. In the Chester Upland School District, just outside of Philadelphia, he noted that the district faced a $22 million deficit at the same time that charter schools in the district were being given $40,000 a year for every special education student they admitted.

In Oklahoma, state lawmakers just this past March defeated a bill that would have dedicated $128.5 million to expanding school choice, because they was feared it would have an adverse effect on rural schools. Green applauded this, and suggested taking a page from environmental law, and mandate that districts conduct an “educational impact analysis” report before allowing charters to open.

California, Kentucky and Missouri have provisions like this in place for urban school districts, and Louisiana has one for rural areas, he noted.

“For districts with fewer than 5,000 students, the Louisiana State Department of Education actually engages in an assessment with the school district to determine whether or not a charter school should open in that rural community,” he said.

Finally he cited predatory contracts, which can often surface when charter schools are not properly regulated. In New Jersey, he said, a 2019 investigation found that some operators treated their buildings like investment vehicles instead education spaces, and non-profit educational entities often worked in tandem with for-profit partners.

Idaho, Kentucky, Ohio, Rhode Island in Texas already have laws that stipulate that real estate purchased with charter school funds belong to the state; Green suggested that in addition to that, a model statute for contracts and purchases should also include a rule that leases and related party transactions must be conducted at fair market value.

“We’re having a debate right now where we’re asking, ‘Should we go forward with charter schools or should we go forward with private school choice programs?’ I’m going to say that right now, I think that train has left the station,” he said.

“But if we’re going to go forward with this, we need to provide protections. This is my attempt really to begin to put the meat on the bones as to how we can actually do that.”

]]>“It’s a historic year, the first time in our history that we had two authors honored, and the first time we’ve had two women honored,” said Father McShane, who presented the award to Kerri K. Greenidge, Ph.D., for her biography Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter and Lesley M. M. Blume, Ph.D., for FALLOUT: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World, about war correspondent John Hersey.

The award ceremony for The Sperber Prize, given in honor of the late Ann M. Sperber, the author of Murrow: His Life and Times, a critically acclaimed biography of journalist Edward R. Murrow, took place via Zoom on Wednesday night. Through the generous support of Ann’s mother Lisette, the prize and its $1,000 award were established to promote and encourage biographies and memoirs that focus on a media professional; it has been presented annually by Fordham’s Department of Communication and Media Studies since 1999.

Beth Knobel. Ph.D., associate professor of communication and media studies and director of the Sperber Prize, said this year’s winning biographies were so well written and researched that the award had to be given to both authors. The winners will each receive $500 as prize money.

Both winners were asked about their inspirations and the research behind the behind writing their books. Both shared that they wanted to write the hidden stories of investigative journalists who documented atrocities happening in their communities and in their country.

“Black stories are always far more complex than we believe. Stories like Trotter’s ought to be as analyzed, discussed, and studied as Dubois, Garvey, King, and Malcolm X,” said Greenidge.

“It has been my hope, with Black Radical, to reorient the scholarship toward these stories, not as a form of hagiography or racial exceptionalism, but as a way to challenge ourselves to more completely reckon with our complicated and often painful racial history,” she said.

Blume explained how the attack on journalists during the Trump era influenced her motivations for writing Hersey’s biography.

“My research coincided with the Trump era. Suddenly and shockingly, America’s best journalists were dubbed enemies of the people by Trump his followers, and journalists began to be threatened,” said Blume. “My entire life, without exaggeration, has been centered on newsrooms and my extended community of reporter colleagues is like family and then suddenly in the Trump era, my family was on a hit list,” she said.

Prompted by Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, both authors discussed journalists as vital figures in enforcing freedom of the press and how journalists are very important documenters of history.

“Trotter was warning about, responding to, protesting, and organizing [to protect]one of his goals as a journalist– to be able to hold a mirror up to nature. The press should be used this way to critique and question power,” said Greenidge.

Blume said that the subject of her book made it impossible to ignore the brutal realities of Hiroshima.

“After Hersey’s report came out, the only way that you could be oblivious to what nuclear warfare portended for humanity and what the Americans have done to win the war was through willful ignorance,” said Blume.

Father McShane shared that he was amazed that he recently discovered the hidden history of the Tulsa Massacre, written about in Black Radical.

“You help us to see the importance and power of journalism, but also the harm of national amnesia,” said Father McShane.

Ann’s brother, Alan Sperber, M.D., and his wife Betty offered their congratulations to the 2021 award recipients and detailed the history of the Sperber family’s close association with Fordham University since Ann’s book was published by the Fordham University Press.

“Throughout his presidency, Father McShane has been an enthusiastic supporter of the Sperber Prize and a close friend of the Sperber family,” said Alan Sperber.

Knobel said that they had considered over 25 books for the prize, including one from Fordham faculty.

“Another book we considered was written by one of our own, our department chair in communication and media studies at Fordham, Amy Aronson. Her book was on the founder of the ACLU, Crystal Eastman, who also did some time as a writer, journalist, and founder of a publication. That is an astoundingly beautifully written and researched book,” said Knobel.

Father McShane said the Sperber Prize has become known for its acknowledgment and support of important biographers.

“This has become one of the coveted prizes in the world of journalism, publishing, and research,” he said.

]]>The Sperber Prize is given in honor of the late Ann M. Sperber, the author of Murrow: His Life and Times, the critically acclaimed biography of journalist Edward R. Murrow. One edition of that work was published by Fordham University Press, connecting the Sperber family to the University. Through the generous support of Ann’s mother Lisette, the $1,000 award was established to promote and encourage biographies and memoirs that focus on a media professional; it has been presented annually by Fordham’s Department of Communication and Media Studies since 1999.

Associate Professor of Communication and Media Studies Beth Knobel, Ph.D., director of the Sperber Prize, said that the jury decided to present the award to two books this year, as each was so deserving of the prize. The two winners will receive $500 each and are invited to speak about their works at a virtual Fordham award ceremony on November 3.

Knobel praised Black Radical for bringing the work of the Boston newspaper editor and civil rights activist William Monroe Trotter to light. “Black Radical is a revelation,” Knobel said. “William Monroe Trotter was truly a seminal figure in the civil rights movement, but his extraordinary life story had been little known by the wider public until Kerri Greenidge brought it to prominence through this book.” Trotter, a Harvard graduate, founded the Boston Guardian newspaper and used it as a platform to call for racial justice in early 20th-century America. “Black Radical is exhaustively researched, beautifully written, and extremely timely. In telling Trotter’s story, Greenidge deftly sheds new light on the entire civil rights movement from Reconstruction into the 1930s,” Knobel said. The book was published in 2020 by Liveright Books, a division of W.W. Norton.

The second winning book, FALLOUT: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World, explores how reporter John Hersey came to expose the U.S. government cover-up of the consequences of the Hiroshima nuclear explosion for The New Yorker in 1946. “FALLOUT cuts to the very core of what makes journalism a valuable public service: watchdog journalism,” Knobel explained. “Blume’s gripping narrative explains how Hersey showed that the U.S. government was lying when it said there were no ill effects from the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima at the end of World War II. Blume’s archival research, done around the world, puts the reader in Hersey’s shoes and in those of his editors at The New Yorker, trying to face down systemic hypocrisy.” The book was published in 2020 by Simon & Schuster.

Kerri K. Greenidge, Ph.D., is Andrew W. Mellon Assistant Professor of Race, Colonialism, and Diaspora and director of the American Studies program at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts. Greenidge received her doctorate in American Studies from Boston University, where her specialty included African-American history, American political history, and African-American and African diasporic literature in the post-emancipation and early modern era. Her research explores the role of African-American literature in the creation of radical Black political consciousness, particularly as it relates to local elections and democratic populism during the Progressive Era. Her work includes historical research for the Wiley-Blackwell Anthology of African-American Literature, the Oxford African American Studies Center, and PBS. For nine years she worked as a historian for the Boston African American National Historic Site in Boston, through which she published her first book, Boston Abolitionists (2006).

Lesley M. M. Blume is a Los Angeles-based journalist, author, and biographer. Her work has appeared in Vanity Fair, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Paris Review, among many other publications. Her last nonfiction book, Everybody Behaves Badly, was a New York Times bestseller.

Previous winners of the Sperber Prize include Working by Robert Caro, Fire Shut Up in My Bones by Charles M. Blow, Cronkite by Douglas Brinkley, Lives of Margaret Fuller by John Matteson, Reporter by Seymour M. Hersh, The Publisher: Henry Luce and His American Century by Alan Brinkley, Avid Reader: A Life by Robert Gottlieb, and All Governments Lie! The Life and Times of Rebel Journalist I.F. Stone by Myra MacPherson. More information about the prize can be found at Sperberprize.com.

The Sperber Prize will be awarded on November 3 at 6 p.m. in a Fordham virtual ceremony that will be open to the public.

For more information, please contact Beth Knobel at [email protected] or 718-817-5041.

]]>

A Boston University law professor and former adjunct associate professor of legal research and writing at Fordham Law School, Citron is one of 26 artists, scientists, and others to earn the award this year.

Commonly known as the “genius” grant, the fellowship recognizes recipients’ “originality, insight, and potential,” and comes with a $625,000 no-strings-attached award to be paid over five years.

In selecting Citron as a 2019 fellow, the MacArthur Foundation praised her for “addressing the scourge of cyber harassment by raising awareness of the toll it takes on victims and proposing reforms to combat the most extreme forms of online abuse.”

Her work, the foundation added, is “spurring legal scholars, lawmakers, tech companies, and the public to view in a new light what many have simply accepted as the inevitable dark side of the digital age.”

Framing Cyber Harassment as a Violation of Civil Rights

In her 2014 book, Hate Crimes in Cyberspace (Harvard University Press), Citron wrote about victims of various forms of cyber harassment, including “revenge porn”—the dissemination of sexually explicit photos or videos of people without their permission. She described how the victims, who are disproportionately women, can have their lives and livelihoods nearly ruined by the experience. And yet, she found, law enforcement did not take these kinds of attacks seriously—or did not fully understand how existing laws could be used to prosecute harassers.

“When I first started writing about the targeting of women and sexual minorities and minorities online in about 2007, the response was just, you know, ‘this is part of online life,’ ‘this is the nature of the internet,’ or ‘this is the nature of humanity in a digital age.’ And the answer is, absolutely not,” Citron says in a video produced by the MacArthur Foundation. “This is not something that we should accept.”

She has called for both legal and social reforms. With federal and state lawmakers and state attorneys general, she has stressed the need to enhance criminal, tort, and civil rights laws, and to use existing statutes to deter and punish online harassers. She also works with companies (she’s an unpaid adviser to Facebook and Twitter) on strengthening online safety and privacy policies and “ensuring that this kind of abuse isn’t tolerated,” she says.

Sounding the Alarm on Deepfakes and the Threat to Democracy

In fall 2018, Citron returned to Fordham Law School as a visiting professor, teaching a course on information privacy law and a seminar titled Civil Rights and Civil Liberties in the Digital Age. She was back again on September 23, just two days before the MacArthur grant announcement, to share her latest research with students and faculty.

In recent months, Citron has been writing and speaking about the legal, ethical, social, and political ramifications of deepfake technology, which allows users to manipulate or fabricate video and audio recordings to show people doing and saying things they’ve never done or said.

Last June, she testified before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, warning legislators that the “technology behind the fakery is poised to take a great leap forward.”

Soon, she said, video and audio fakes will be impossible to distinguish from the real thing. “Under assault will be reputations, political discourse, elections, journalism, national security, and truth as the foundation of democracy.”

She has been urging U.S. presidential candidates to prepare to defend themselves from hard-to-debunk deepfakes, particularly during the leadup to the 2020 election.

The dissemination of a deepfake showing “a candidate in a tight race doing something shocking [they] never did … could alter the election’s outcome,” she told the House Intelligence Committee. The creator of such a forgery “could be a hostile state actor or non-state actors motivated to sway the election a particular way,” she added. “No matter, the damage would be irreparable.”

No Easy Solutions

There are no easy answers to these concerns, she told lawmakers, and everyone has a part to play. “We need the law, tech companies, and a heavy dose of societal resilience to make our way through these challenges,” she said.

In July, one month after testifying before the House Intelligence Committee, she delivered a TED Talk in Edinburgh, Scotland, stressing the need for “a coordinated international response.” The video of her talk, “How Deepfakes Undermine Truth and Threaten Democracy,” has received more than 800,000 views.

“Education has to be part of our response as well,” she said—education for law enforcement officials about the tools available to them, and education for journalists and citizens to help ensure that they don’t “amplify and spread” deepfakes.

“Each and every one of us needs educating,” Citron said. “We click, we share, we like, and we don’t even think about it. We need to do better. We need far better radar for fakery.”Watch Citron’s TED Talk

Fordham’s MacArthur Fellows

Citron is the second Fordham graduate to be named a MacArthur fellow. Msgr. William J. Linder, a community development leader in Newark, New Jersey, was named a fellow in 1991, three years after he earned a Ph.D. in sociology at Fordham’s Graduate School of Social Service.

Two other members of the Fordham community have been named MacArthur fellows. Ann Ellis Hanson, Ph.D., a historian who taught at Fordham from 1968 to 1975, earned a MacArthur fellowship in 1992 for her work in classics, late antiquity, and medieval studies.

And longtime Fordham Law Professor Jennifer Gordon, who specializes in immigration, employment, and public interest law, was named a fellow in 1999. She has been a member of the Fordham faculty since 2003.

]]>

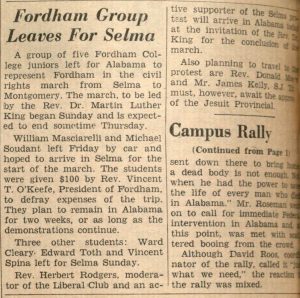

On March 25, 1965, Martin Luther King Jr. led thousands of nonviolent demonstrators to the steps of the state capitol in Montgomery, Alabama, after a five-day, 54-mile march from Selma. There, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and local African Americans had been campaigning for voting rights.

Some Fordham students and administrators were among the marchers. One of them was Ward Cleary, FCRH ’66, LAW ’69.

What prompted you to travel to Selma?

I was pretty incensed about what was going on down there. I’m not particularly liberal, but when people were shot, nobody seemed to care about bringing the guilty to justice.

What do you remember about the trip?

What do you remember about the trip?

I remember that someone else had the idea to ask Fordham’s president [Vincent T. O’Keefe, S.J.] for travel money, and he gave us each $100. We took the train down, and there were some volunteers down there who met us. We were there for four or five days, and we just helped out, dispensing food and things like that.

I remember marching. When you looked out, there were a lot of onlookers on the sidelines who were sullen. No one was cheering. At every corner there was a local policeman, and next to him, someone from the state police, and next to him, [a member of] the National Guard. There were three levels almost everywhere, because most of the authorities were hostile to this march and to the black movement. These big farm guys came from out of the crowd and started beating on some African-American that they knew. They were pulled off, [but] not arrested or anything.

After the march, there were speeches and a concert. The groups were huge, and I wasn’t close enough to hear or follow anything that well. I took a bus back, and I was alone at that point. It was pretty obvious I was a student and was probably down there for those purposes. But people I talked to on the bus were nice enough. Even when they didn’t agree with me, they were pleasant.

Had you participated in a protest before this?

No, I was fairly nonpolitical. But you heard on the news about bombings and murders, and there was no real pursuit by legal authorities. It was something that really bothered me. That’s what got me to go down there and protest.

Did you ever protest anything after that?

In 1970 and 1971, I worked in Washington, and I was in one antiwar march. By then, the war was pretty unpopular. But that was it for me. As I said, I never considered myself political. But some of these things just get you angry.

What was it like when you came home?

I feel like I was part of a movement that was good. I’m glad I went. But I never thought of it as, ‘Gee, I got something done.’ It was just a way to get your views across. There were some risks, in retrospect, but … either I didn’t know or I didn’t care. I thought it was worth doing.

“The first thing to know is that these are two different words with two different meanings,” Rather told an audience at a Q&A event organized by Fordham’s Francis and Ann Curran Center for American Catholic Studies on Feb. 15. “The heart of patriotism is humility. The heart of nationalism, though, is a breast-beating conceit or arrogance.”

The Emmy Award-winning journalist said some of the values that are rooted in America’s national identity include public education, freedom of the press, and inclusion.

The Emmy Award-winning journalist said some of the values that are rooted in America’s national identity include public education, freedom of the press, and inclusion.

“The appeal of America worldwide is the essence of the idea and the ideal,” said Rather. He recently published What Unites Us (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2017), a book of essays on American values.

A Voice of Reason

Though he stepped down from his CBS Evening News post 13 years ago, Rather continues to weigh in on the issues he feels are shaping the United States and the world at large. He has more than 2.5 million followers on Facebook, a platform he said is allowing him to remain a “steady, reliable voice of reason that can put events into context and historical perspective.”

Now 86 years old, the veteran journalist said one of the major divisions among American citizens today revolves around race. He described his first major news assignment covering the beginnings of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. He said the first time he saw a KKK rally, the “hair on the back of my neck stood up.”

“I thought to myself, “If I—a white person with a press tag—if this has this kind of effect on me, what effect could it possibly have on African-American families and their children?” he said.

Having been on the front lines of some of the country’s biggest news events—from John F. Kennedy’s assassination to Watergate to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—Rather said that “every generation is tested.” He maintained, however, that the values that have defined the country for centuries are what has carried it through “bad times.”

“There’s a great struggle going on, a struggle for the soul of our country,” he said. “Who are we as a country? What are we about? [Those are questions that are] being decided now.”

Protecting a ‘Great Historical Experiment’

Rather expressed special concern about the escalating attacks on the free press, which he argued are an attempt to evade checks and balances on people in positions of power.

“We need to see clearly that a truly free and fiercely independent press is the red beating heart of freedom and democracy,” he said.

He said that America has gone through major transitions that have led to fear among some of its citizenry, starting with the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965.

“The demographic of the United States changed so dramatically in the wake of that immigration reform that this country today is not recognizable to a lot of people, particularly those at the lower end of the socioeconomic scale,” he said. “They’re fearful about the jobs at stake, but even more, I think they fear [a]change in the [American] culture.”

Calling the formation of the United States of America a “great historical experiment,” Rather said America’s ability to remain a united front could prove difficult without a firm commitment to its founding principles.

“This idea and ideal is not an empty hope,” he said. “If we put our minds to it, if we stick to this willingness of heart, then we’re going to be okay.”

Photo by Bruce Gilbert

]]>

Photo by Chaewon Seo

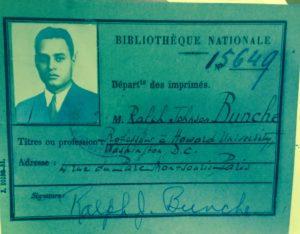

Christopher Dietrich, Ph.D., an assistant professor of history at Fordham, is at work on a biography of Bunche. It’s not the first, but he hopes it will bring to the fore new ideas about 20th-century politics, society, and foreign relations. Dietrich is one of five scholars nationwide to receive the 2016 Nancy Weiss Malkiel Junior Faculty Fellowship from the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, which he will use to do research toward the book, titled Tortured Peace: Ralph Bunche, Race, and UN Peacemaking.

“Ralph Bunche hated being identified as the first person of color to do things, but he was a trailblazer,” said Dietrich.

Bunche’s life as a scholar, diplomat, peacemaker, rights activist, and intellectual spanned the critical decades of the 20th century—from the 1920s to the 1970s. It was a time, said Dietrich, when tumult both at home and abroad ran high, and Bunche came to be at the center of new ideas about race and oppression as “probably the most well-known black person in the world after having won the Nobel Peace Prize.”

The Talented Tenth

Bunche had early aspirations to be one of W.E.B. Du Bois’ Talented Tenth, Dietrich said, a group of elite African-American scholars who could serve as thought leaders for their race. Following his graduation from UCLA in 1927 (he was valedictorian of his class), Bunche went to Harvard and became the first African American to earn a doctorate of political science from an American university.

Photo by Chris Dietrich

Dietrich’s initial interest in Bunche arose from reading the scholar’s Harvard dissertation on African colonialism and the mandate system at the League of Nations. Bunche had done fieldwork research in French West Africa, and his analysis of colonialism, global oppression, and political systems was “strikingly radical” for its time, he said.

“His dissertation sits somewhere in between Lenin and the West in its critique of colonialism as an oppressive capitalist system,” said Dietrich. “He believed strongly in independence from colonial rule.”

At the same time, says Dietrich, Bunche’s overview in the 1930s was shaped by his radical belief that class trumps race in the fight to overcome oppression. “He believed in order for there to be a change in the political system, the white working class and black working class needed to form a coalition,” and that, globally, those under colonial rule no matter the race—Africans, Asians, Middle Easterners, Indians, and others—all shared a similar “self-aware spirit of hopefulness” that they’d be able to conquer racist systems.

“This is an African-American man saying this—someone who assigns Marxist economic tracts to his students,” said Dietrich. “It was radical.”

Bunche and the U.N.

Enter World War II. Already a well-respected Howard University professor, Bunche was summoned by the Roosevelt Administration to work in the Department of State, said Dietrich, as one of the nation’s leading experts on African-continent colonialism. He then became involved in the planning for the United Nations (to replace the League of Nations), and was instrumental in writing certain articles in the U.N. charter.

“Bunche presses for, and in fact partially authors, clauses in the charter that allow colonized peoples to make direct reports and demands [for ending colonial rule] of the U.N.,” he said.

Such work, he said, had a “quickening effect” on the process of decolonization around the world. From the U.N.’s founding in 1948 into the end of the 1970s, the member nations grew from the original 51 to more than 150—many of them African, Asian, or Middle Eastern former colonies that arrived at independence.

Nobel Undertakings and Civil Rights

As the visibility of race and globalism advanced, Bunche’s expertise was in high demand, said Dietrich. As the director and key player in the U.N. Observer Group in Palestine, he became the lead negotiator in the 1948 Arab-Israeli conflict, implementing first a cease-fire and then the armistice agreement. For his peacekeeping role, he was awarded the 1950 Nobel prize.

When the Civil Rights movement came into its own in the second half of the 20th century, Bunche was a solid supporter, yet grew “deeply critical of the more radical side” of the movement, said Dietrich, due to his strong commitment to peacemaking. He locked arms with Martin Luther King Jr. in the Selma march and marched on Washington in 1963. But he grew disillusioned with certain activist and separatist factions and their leaders, including Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael.

“Carmichael famously said ‘You can’t have Bunche for lunch,’” said Dietrich—the suggestion being he was considered a lightweight by radical black activists.

Dietrich said Bunche continued working at the U.N., negotiating peace efforts in the Congo and being an outspoken critic against the Vietnam War, until his death in 1971.

“Bunche’s life was very particular to the mid-20th century and the major challenges facing the nation and world—whether it was civil rights at home or decolonization abroad,” said Dietrich. “Through his biography, we have a chance to see how somebody with a penetrating intellect and forceful presence navigated the great moments of his day when universal questions come into play—the tension between idealism and pragmatism, the work necessary to find justice and peace. These are some questions that are forever relevant to the human condition.”

]]>Although the collages are striking, the sites themselves seem unremarkable: A hair salon, a burger joint, street corners, churches, and other locales bear little to no trace of their fraught past. Some of the titles, however, underscore Ruble’s concern with the “ways we remember—and forget—the charged events of our country’s turbulent history of race relations,” she writes. A Jersey City sidewalk scene, for instance, is called Everyone here is aware of what has happened but they also want to forget as quickly as possible.

Ruble, who has taught in Fordham’s visual arts department since 2001, created the collages over the past few years. She first showed them last fall at the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey and again this past winter at the Foley Gallery on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. She spoke with FORDHAM magazine via email in April.

As you researched these sites, did you learn anything that surprised you or ran counter to your sense of New Jersey’s place in U.S. history?

Oh my gosh, yes! I’d always known that the North’s relationship to slavery was a complicated one, but one thing that really surprised me was that New Jersey was known as the “slave state of the North.” In 1846, it enacted an abolition law that freed all black children born after its passage but designated the state’s remaining slaves as “apprentices for life.” Eighteen of these “apprentices” still remained in 1860, making New Jersey the last Northern state to enslave people. I was also surprised by just how few white Northerners supported the Underground Railroad.

Did you have a hard time finding and getting access to safe-house locations?

It’s ironic—in its day, the Underground Railroad was a highly unpopular movement among Northern whites, and also highly illegal, of course. Participants had to operate in secrecy. Today, on the other hand, it’s held up as evidence of our country’s inherent morality, and everyone with a trap door or passageway in the basement likes to speculate that their home was part of the effort to help fugitives escape. I didn’t have a hard time finding or getting access to the safe-house locations—what was harder was actually confirming that they were genuine.

Which riot locations did you depict in the series?

The state had five major race riots—in Jersey City, Paterson, Newark, Plainfield, and Asbury Park. They all happened in the 1960s, except for Asbury Park, which took place on Independence Day, 1970. When I first began this series, I’d planned to depict the place where the riots “started.” But that quickly grew complicated as I got further into my research. Was the “start” of the riot the street corner where the first brick or Molotov cocktail was thrown? Or was it where the precipitating event occurred—for instance, where the Newark police arrested and brutally beat a black cab driver who’d done nothing more than pass a double-parked squad car? Identifying where something supposedly began is freighted with judgments about guilt and responsibility. Looking at the longer arc of history, you can easily make the case that all of the riots actually began with the original violence of slavery—there’s a direct line from slavery to Jim Crow to the uprisings of the civil rights era, which were a response to centuries of horrific brutality.

Tell me about Everyone here is aware of what has happened but they also want to forget as quickly as possible. Why did you choose that title for the piece?

All of the pieces that depict riot sites are titled with sentences taken from contemporaneous newspaper reports of the incidents. That particular sentence struck me not only as having an obvious connection to the feelings of the time but also as symbolizing how many have come to view the uprisings of the 1960s, 50 years later—as shameful events better left out of the history books because they threaten the dominant narrative of our country as a land of opportunity and freedom.

Why are the safe-house locations called Untitled with the name of the town in parentheses?

I left the Underground Railroad sites untitled to allude to the secrecy that shrouded them in their day. I thought a lot about the idea of silence while making this series, and how silence has many different connotations. In the context of the Underground Railroad, silence was used as a tool of protection. But there’s also silence—or more accurately, silencing—that occurs in the context of oppression. Martin Luther King referred to the riots of the civil rights era as “the language of the unheard.” And finally there’s the silence of the landscape itself, which swallows the secrets of its past with every big-box store and parking lot that’s laid down on historically significant ground.

You took the title of your series from the 1965 Flannery O’Connor short story “Everything That Rises Must Converge.” Why did you use those words to unite the collages you created?

These places, both the Underground Railroad sites and the race riot sites, were about rising—rising up, rising against—and about convergence, in both cooperation and conflict. [O’Connor’s story is] about an altercation between a white woman and black woman riding a bus in the South shortly after the desegregation of the transportation system. The fact that the story is about race relations—and about the complicated relationship between forward and backward movement—just underscored the fact that it was the right title for my series.

The title isn’t original to O’Connor. She took it from the Jesuit scientist and philosopher Teilhard de Chardin, who wrote about spiritual evolution. Do you feel you’ve transformed the title in some way with your work?

I haven’t studied Teilhard in as much depth as I’d like to, but my understanding is that he believed that creation was not a singular event but rather an ongoing development—that evolution was a spiritual and moral progression toward a point associated with Christ. I think O’Connor recognized that we are only partway through that progression toward convergence with Christ, and I think her story is about the messiness of that trajectory. My adopting of her title 50 years later is not so much a transformation of its meaning as it is an accounting of our progress. How much closer are we to Teilhard’s convergence? Perhaps not as close as we should be. But I don’t see this strictly as a condemning fact. I see it as a call to rise to everything we as a nation have claimed to believe in. As a call to keep struggling toward grace.

You’ve written that the collages depict a “present that’s unmoored from its past but never perfectly free from it.” Is that a good thing? Should we be free from the past? Or have you tried to bring about a kind of artistic convergence of past and present?

I’m tempted to say, yes, that’s exactly what I’m trying to do. But actually I think the collages do just the opposite—they talk about our disconnect from the past. Or maybe they do both. In the course of making this series, I’ve thought a lot about remembering and forgetting, and when each is “better.” Let’s for a second assume that the entire nation could completely forget our history. That we all woke up tomorrow with amnesia. We would presumably recognize difference in skin tone, but what would we make of it? It would be an interesting experiment—maybe we’d all get along better, maybe not.

As a white woman, I’ve also thought a lot about the implications of looking so closely at white-initiated violence against black communities and individuals. Does this focus just ossify modes of oppression and perception that still exist? Does it suppress stories about black achievement and triumph? Or is it a critically needed acknowledgment of the white community’s wrongdoing? An attempt to take responsibility for the past and move forward, in whatever way that may mean?

Has the Black Lives Matter movement influenced your work or your thinking about this project?

I started this series a year before the events in Ferguson, well before the Black Lives Matter movement. Although I came to the series through my earlier interest in conflict in general, the project obviously immediately became one about past and contemporary race relations. It was a subject that wasn’t dominating the national conversation in the same way it is now, and the series was my own small attempt to open up that conversation. The Black Lives Matter movement has moved the conversation forward in much more effective, widespread ways, of course. Last year I participated in a march in New York City for Eric Garner. Along with about a hundred other people, I laid down in a street near Penn Station. After two years of visiting past riot sites on my own, in a very solitary way, it was an incredibly moving experience to be among hundreds with a collective voice strong enough to bring the city to a screeching halt. It felt like stopping the heart of the city and pushing the blood in a new direction, toward extremities that hadn’t been receiving enough of it.

New York Times art critic Ken Johnson described your collages as being “deadpan cool” but conceptually “loaded” and “painfully hot.” Is that hot and cool combo something you wanted to convey?

Definitely. Conceptually, this is a very loaded topic to address. And I’m an artist, not a scholar, on these subjects—it’s not my place to offer any kind of “authoritative” statement. The only way I personally feel comfortable addressing race relations is by looking in a very objective, “deadpan cool” way at how these sites of historical significance have changed over the years. What gets lost? What gets remembered? To what end? The answers to these questions help give us a sense of where we are today and what we need to work toward.

What would you like viewers to take away from the project?

I’d love for viewers to come away from it looking more closely at everything that surrounds them—being curious about hidden narratives. Areas that are economically depressed are rendered anonymous—or worse, as “dangerous” or “blighted.” Disconnecting communities from their history in this way is a powerful means of perpetuating their oppression. Regardless of where you live, that place has a history. Maybe a Walmart sits on it. Maybe it’s just an empty lot. The present often obliterates the past. But knowing the past may give you a sense of agency you might not have had otherwise.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Ryan Stellabotte.

]]>A memorial service for Parker will be held on Saturday, Oct. 3rd at 11 a.m. at the Church of the Highlands in White Plains.

A minister and director of communications for the United Church of Christ in the 1960s, Parker petitioned the Federal Communications Commission to deny the renewal of a broadcast license to a TV station in 1964 for its failure to serve the public interest, as required by law.

He argued that although blacks made up 43 percent of the viewing audience, the station, WLBT in Jackson, Mississippi, did not cover civil rights news or the black community, and often referred to blacks pejoratively on the air. In 1969, future Supreme Court chief justice Warren E. Burger, then a federal appellate judge, agreed.

It was the first time that a license was lifted for a broadcast station’s failure to serve the public interest, and it ushered in an era in which activists, such as Parker and Ralph Nader, monitored and challenged broadcasters both on content and discriminatory hiring practices.

Parker joined the Fordham University communications and media studies faculty as an adjunct professor in 1983. He taught well into his 90s.

He co-founded the Donald McGannon Communication Research Center in 1986 with colleague Jack Phelan, professor emeritus of media and politics. The center is dedicated to furthering understanding of the ethical and social justice dimensions of media and communication technologies, particularly how such technologies affect the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within society.

“All we’ve ever wanted to do is make it possible for people to express themselves through the system of broadcasting,” he told The New York Times in 1983.

“If broadcasters are to serve the public interest, they need to be reminded that they serve all the publics.”

Former WFUV Manager Ralph Jennings joined Parker’s team at the United Church of Christ shortly after the initial challenge to FCC and worked for him for 12 years. He based his doctoral dissertation in part on Parker’s work.

“Right out of graduate school Everett offered me a job. It was a chance to take all that idealism and do something with it,” he said.

“Because of the things that he let the staff do, because he trusted them, and he knew they would do things his way, it was great thing to work for him. He was tough, but he was a compassionate person as well.”

Gwenyth Jackaway, PhD, associate chair of the Department of Communication and Media Studies, also met Parker when she was a graduate student and was becoming “disillusioned” with the slow pace of change in the industry. She recalled asking him how he managed to keep cynicism at bay as he fought the FCC and corporate media.

“The spirit of his response has stayed with me to this day. ‘We keep working towards reform,’ he told me, because there is no other choice. Giving up the fight is not an option. Working to bring about change gives purpose to our professional lives,” she said.

“There is no question that Everett Parker saw his media reform activism as doing God’s work in the world. He was an incredible inspiration, and was a staunch defender of the true spirit of what was originally intended by those who envisioned the broadcast media as servants of the public interest.”

Paul Levinson, PhD, professor of communication and media studies and former chair of the department, recalled that students regularly asked him how they could get into “Ev’s” course.

“He was in his 90s then, and had more energy than many faculty half his age. Fordham was fortunate indeed to have him in our midst,” he said.

Parker is survived by his daughters, Ruth Weiss and Eunice Kolczun; a son, the Rev. Truman E. Parker; seven grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

In lieu of flowers, contributions may be sent to the Emma L. Bowen Foundation, 300 New Jersey Avenue, N.W., Suite 700, Washington, DC 20001, or to the UCC’s Office of Communication, Inc.

]]>What is significant about this 50-year-anniversary to you?

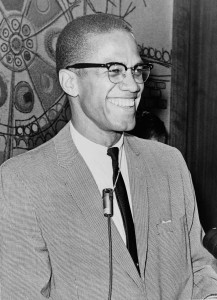

It means something very different right now than it probably would have if it had come two years ago. We’re in a very exciting and potentially transformative time, particularly in the United States, in how we think about the question of race. And particularly what it means for us to understand that race is a social construction and also to understand that it has very real lived consequences for lots of people in ways that reinforce social inequity.

I think it has everything to do with what’s been happening here around state violence. People are questioning everything from ‘stop and frisk” to the deaths of Mike Brown and Eric Garner.

Does an anniversary like this focus people’s attention on the past?

It does. It forces young people to ask, ‘Ok, so what is different?’ There are things that Malcolm X was speaking to and fighting against, and they can ask ‘Wow, how much has really changed?’ It compels them to connect the dots from the history to the present.

Is there is any one person today who embodies his message?

No. What’s powerful is that to some extent this has always been the case. When we talk about the civil rights and black power movements, we think of key figures like Martin Luther King, Huey Newton, Angela Davis, and Malcolm X. But there were always masses of everyday people–collective energy and organizing–who were meeting in their kitchens and in community centers.

The difference today is that that collective organizing is more visible. So we’re not necessarily seeing these individual figureheads. Think about the hash tag #blacklivesmatter. When we tell a story about a place in history, we look for singular figures that we can say “led” this movement, but today it’s almost impossible because it’s happening in Ferguson, in Brooklyn, and all over.

What do you think Malcolm X’s legacy is?

The phrase ‘the personal is political’ is used so much that it’s sort of lost meaning. But if we think about educating the whole person, Malcolm X’s life is a very clear example of that. We have to first think about the transformations that need to happen in our thinking and our own actions before we can address the larger social structure.

It’s not just marching in the streets, signing this petition, or protesting a thing as if we are somehow outside of that process. We have to question the ways that we act, the ways that we confront, ignore, or step outside of justice in our everyday lives. His life is a very clear and powerful testimony to the fact that the personal is the political.

The other phrase he’s known for is “by any means necessary.” After all this time, is there still confusion surrounding his legacy?

Because Malcolm X was so transparent about his experiences in prison and with illegal activity, he was always more of a taboo figure. Martin Luther King is a much more palatable figure to talk about, especially in educational settings—even though we know his life was not all that clean and easy. That is changing now because we’re acknowledging bias in things we’ve taken for granted as neutral—like the legal systems—and we understand better how poverty works and the choices that some people have or don’t have. Today, Malcolm X is worthy of being acknowledged and celebrated as a complicated human being, and not as an iconic figure.