That was one of the many topics debated on by leading philosophers from the U.S. and China at the New York-China Epistemology Conference held at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus from Oct. 18 to 20.

Their talks covered a variety of topics, including “Intuition, Understanding, and Self-Evidence,” “Imagination and Understanding,” and “Can Closed-Mindedness be an Intellectual Value?” And the scholars who delivered them were just as diverse. Among them were U.S. philosophers from schools including Harvard, Princeton, Cornell, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as well as Chinese scholars from highly ranked universities like Peking, Fudan, and Nanjing.

“A Model of International Cooperation”

Their lectures explored the research of past philosophers and their own. About half of the presentations were accompanied by commentary from their peers. For example, after an MIT professor spoke about “Higher Order Evidence and the Perspective of Doubt,” a Chinese epistemologist critiqued and reflected on her work.

“I was hoping that the conference would lead to deep and lively exchanges about issues of common concern in epistemology [the study of knowledge, particularly with regards to its validity and scope], and I’m delighted to say it did,” said Stephen Grimm, Ph.D., Fordham’s philosophy department chair. “I was also hoping the conference would provide a model of international cooperation between our countries—and on that score too, it exceeded all my expectations.”

To Assert or Not to Assert?

One of the Chinese philosophers was Weiping Zheng, a scholar from Xiamen University. His topic was “Norms of Assertion and Chinese Speech Wisdom,” which explored the rules that allow us to state a fact or a belief, what kinds of assertions we should make and shouldn’t make, and how ancient Chinese wisdom can help us evaluate what we should say before we actually say it.

One rule of assertion, he said, is that we should only assert things that are true. Zheng argued that this rule is too restrictive. Some assertions may be true, but morally wrong.

“For example, [let’s say] I am dying. And you say [to me], you are dying. You are epistemically right, because it is true that I am dying. But you think it is morally right [to say this]?” he asked. “That’s why I want to find hierarchy of different norms of assertion.”

One way to help you make morally sound assertions, he continued, is by following a Confucian concept called Li—an ancient Chinese form of wisdom.

“It’s part of [this] wisdom that we’re gonna be virtuous, good, kind, proper, and all of these things. We’re thinking of that as the thing we’re always supposed to be answerable to,” explained Jane Friedman, a philosophy professor at New York University, who also delivered a lecture at the conference. “Whereas if all you have is a rule that says, ‘Yeah, if something’s true, it’s okay to say it’ … I think part of what he wanted to drive home was no, of course that’s not fine. We need another kind of principle governing what we’re allowed to say and when. The place to look to is this notion of Li in Chinese philosophy.”

This includes using discretion in speech, said Zheng, using solid evidence when making assertions, and keeping virtue in mind while speaking.

“It does seem like an interesting guide and a way of thinking in a more holistic way about the practice of asserting things,” Friedman said. “I like thinking about this general idea of wisdom, what that might entail, and how it might be a guide to what I should say and when.”

]]> In 2011, a series of uprisings known as the Arab Spring briefly gave the impression that democracy was on an unstoppable march across the globe. Seven years later, it hasn’t exactly turned out that way. Egypt has embraced authoritarianism, Libya is in a state of near anarchy, and Syria has been mired in a catastrophic civil war for seven years. Meanwhile, the international influence of authoritarian countries such as China and Russia has grown significantly.

In 2011, a series of uprisings known as the Arab Spring briefly gave the impression that democracy was on an unstoppable march across the globe. Seven years later, it hasn’t exactly turned out that way. Egypt has embraced authoritarianism, Libya is in a state of near anarchy, and Syria has been mired in a catastrophic civil war for seven years. Meanwhile, the international influence of authoritarian countries such as China and Russia has grown significantly.

John Davenport, Ph.D., a professor of philosophy, says these and many more developments are proof that NATO and the United Nations Security Council, the two bodies best equipped to promote human rights and peace, are no longer up to the job. In a book that will be published by Routledge this fall, Davenport makes the case for creating what he calls a “League of Democracies.”

Listen below

And in an extended bonus track, Davenport delves into the ways in which game theory explains how the challenges the world’s democracies face are similar to those that America’s founding fathers faced in the 18th century.

Full transcript below

John Davenport: The goal of this proposal is not to create an entity that would take over the whole world. It’s to create a new organization that could protect democracies from the rising threats posed by Russia and China, and to stop the enormous mass atrocities that keep coming at us wave after wave.

Patrick Verel: In 2011 a series of uprisings known as the Arab Spring briefly gave the impression that democracy was on an unstoppable march across the globe. Seven years later, it hasn’t exactly turned out that way. Egypt has embraced authoritarianism, Libya is in a state of near anarchy, and Syria has been mired in a catastrophic civil war for seven years. Meanwhile, the international influence of authoritarian countries such as China and Russia as grown significantly.

John Davenport, a professor of philosophy at Fordham, says these and many more developments are proof that NATO and the United Nations Security Council, the two bodies best equipped to promote human rights and peace, are no longer up to the job. In a new book that will be published by Routledge this fall, Davenport makes the case for creating what he calls a league of democracies. I’m Patrick Verel, and this is Fordham News.

What was the genesis of this book, was there one particular moment that made you think, “You know what, let’s just start all over?”

John Davenport: In a word, Syria. I think the idea for the book really came to me in the summer of 2013 when it became clear that no nations were going to do anything about the new genocide in progress. After seeing this go on for decades, in the period we thought the world was going to get better after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Instead, we had Bosnia, we had Rwanda, we had the slaughter in the Darfur region of Sudan. All of the mass movements of refugees that these crisis cause. The civil war in Libya. There just isn’t a system in place in the world today to prevent mass atrocity crimes that destabilize whole regions.

Patrick Verel: What do you think is the most pressing concern for liberal democracies today?

John Davenport: Clearly we have division among democracies across the world. Those tensions are being aggravated by China and Russia, which are trying to buy off and woo many of these democracies. That’s not something that Western democracies should take sitting down. We need some new system that can unite the will of democratic countries and assure each of those nations that others are going to do their fair share in order to have a real security arrangement that can stand up to the new threats of cyber attacks, of endless hacking of our elections. New technology, unfortunately we’re going to face armed satellites, robotic weaponry, even nanotechnology. Now we have microwave attacks on our diplomats.

Patrick Verel: President Trump’s American First posture has been described by many as a form of isolationism, which would seem to preclude any acceptance of another international body. What do you think needs to happen for that to change?

John Davenport: It’s a natural reaction for people when faced with huge challenges to retrench and say well if we just retreat within our own borders we can weather out the storm that way. Unfortunately, that’s like the illusion that the hobbits suffered from in The Lord of the Rings. If we just stick to our own affairs in the Shire we don’t have to deal with these larger problems. That’s not how the world works. Things are going to get worse and worse in the 21st century as we approach peak population, not only with climate challenges but with pandemic diseases, financial instability across the world, mass movements of people driven by mass atrocity crimes and rising dictatorships.

The United States has to give up the pretension that we can take unilateral action whenever we want to, as we did in 2003. But, I don’t think that would be a huge price for a lot of Americans now, so ironically it might turn out that the isolationist tendency could even help this argument. But then, in other parts of the world, like Europe would have to accept that in order to get the multilateral decision making that they want, they have to be willing to go outside the U.N. Security Council. It’s now proven beyond any shadow of a doubt that this system is never going to work.

If 500,000 people can be killed in Syria with no forceful response, it’s time to abandon the Security Council. By the way, I should note, I don’t propose abandoning the United Nations entirely. This proposal is simply a replacement for the security council. It provides a way for democracies to act outside the purview of the security council, so we no longer give Russia and China a veto over what we’re doing.

Patrick Verel: Now, I understand that the Federalist Papers are actually a source of inspiration for this plan. Can you explain that a little bit more?

John Davenport: Yes, it’s amazing how exactly the situation between nations in the world today fits the analogy of the relation among the 13 young states in the founding of the United States. During the revolutionary war and the period immediately after, we had enormous discoordination among the 13 states. They were being played off against one another by old European powers. They couldn’t form any common foreign policy. They couldn’t even raise revenue to pay their debts or pay their veterans.

The whole relationship among them was falling apart and easily could have devolved into civil war a lot earlier in American history, if it wasn’t for the intervention of Alexander Hamilton with his friends Madison and Jay, who were able to make very powerful and convincing arguments that these problems. The collective action problems is what is the technical term for them between the 13 states, could only be overcome by a strong central authority that could make decisions for all of them and have binding power to enforce those decisions.

That’s exactly what the United Nations Security Council, NATO, and even the European Union for the most part really lack today. All of our international bodies make decisions by consensus, which means that almost every member nation has to agree. That’s how the old American confederation worked, or rather didn’t work, and that was precisely Hamilton’s insight.

Patrick Verel: Have you thought about any unintended consequences that might happen in the event that something like this actually is put together?

John Davenport: Absolutely, there are a lot of possible objections to the plan. Of course the most likely one is you’re going to create a massive leviathan, a world government that’s going to tyrannize humanity for the remainder of our future. The goal of this proposal is not to create an entity that would take over the whole world. It’s to create a new organization that could protect democracies from the rising threats posed by Russia and China, and to stop the enormous mass atrocities that keep coming at us wave after wave. It’s got to be, in my view, a directly elected council. So that, in unlike the U.N. Security Council, it’s answerable directly to people in all of those democratic nations.

It has to have real enforcement powers. It has to have at least a small armed force of it’s own that the council together with the chief executive of the league can deploy when they see that that’s really necessary to prevent new waves of ethnic cleansing or genocide.

Patrick Verel: When I ask about unintended consequences and you mention this idea that oh, it’s not meant to be this world wide government, it allows for freedom. One of the things that dawned on me was, okay, so if you had like a Libya where they fell apart and you did have this league, and the league decided okay, we’re going to go in and we’re going to stabilize it. What happens when China and Russia they’ve formed their own little alliance and they decide, well no, they say they want us to come in and help and we’re going to send in our own troops. Then you end up with a sort of a proxy war.

John Davenport: The first thing to say about Libya, the lack of reconstruction. That’s a case where there was an assurance game between nations and no one nation wanted to be stuck with the bill and the quagmire like what we went through in Afghanistan and Iraq. So, the advantage of a league of democracies is that you could have 30 or 40 nations contributing, so the cost on any one of them is small. You could have a large presence of peace keepers there for 20 years or more and yet, the burden on any one nation is really very small.

Now, the possibility of a league of dictators, Robert Kegan has addressed this. I argue about this in the book that I think it’s very unlikely, although China and Russia are attempting to ally these days and trying to bring other smaller countries into their orbit. I think once there was serious pressure on them from a league of democracies, it would be very hard for them to continue that posture. Unless we wait too long until China’s so big that it’s got most of the worlds economy in it’s pocket. I think actually a league of democracies could simply use trade sanctions to put enough pressure on China that they would probably have to democratize.

Once either China or Russia join the league, well it’s game over. The other one would never be able to continue completely isolated. The problems that are posed by Russia and China today, the rise of their despotis model where you’ve got economic growth without political rights, that would be ended. The future of humanity would be much brighter. It would also be easy for example with a league of democracies to get China to do what it needs to, to disarm North Korea. Can you imagine what trade sanctions between 40 nations that controlled 80% or more of the worlds economy would do to China? They couldn’t withstand a month of that. The regime would collapse within weeks.

Bonus Track

Patrick Verel: Now I understand that the Federalist papers are actually a source of inspiration for this plan. Can you explain that a little bit more?

John Davenport: Yes. It’s amazing how exactly the situation between nations in the world today, fits the analogy of the relation among the 13 young states in the founding of the United States during the Revolutionary War and the period immediately after. We had enormous dis-coordination among the 13 states, they were being played off against one another by old European powers, they couldn’t form any common foreign policy, they couldn’t even raise revenue to pay their debts or pay their Veterans. The whole relationship among them was falling apart and easily could have devolved into Civil War, a lot earlier in American history, if it wasn’t for the intervention of Alexander Hamilton with his friends, Madison and Jay. Who were able to make very powerful and convincing arguments. That these problems, the collective action problems, is the technical term for them between the 13 states, could only be overcome by a strong central authority that could make decisions for all of them and have binding power to enforce those decisions.

That’s exactly what the United Nation Security Council, NATO and even the European Union for the most part, really lack today. All of our international bodies make decisions by consensus, which means that almost every member nation has to agree. That’s how the old American Confederation worked, or rather, didn’t work. And that was precisely Hamilton’s insight.

Patrick Verel: The Federalist papers though, they wrote those in like what, 1780-something? How is that relevant to today?

John Davenport: Well what’s interesting about it is that, although they didn’t use these phrases. The problems that Hamilton, Madison and Jay saw between the states were basically, games of chicken where they’d each wait for other states to do the hard work like, sending troops to Washington’s army, prisoners dilemmas where they would compete with each other to have better trade deals with other nations. And assurance games, which is less of a familiar term, but that stands for cases where the parties will only act together if they have enough trust in one another to do what’s needed for their collective good, so they don’t waste their resources. These are exactly the problems that we see among governments around the world today, SERI is basically a game of chicken. Nobody wanted to intervene. It’s a losing game of chicken, where everybody goes off the cliff.

And, like in the old car chase. In the case of preventing pandemics, like with the Ebola crisis. The U.S. did the work mainly, to prevent the last one from spreading around the world. Prisoners dilemmas, well climate change is a prisoners’ dilemma and nations are not cooperating well enough with each other because, they each gain an advantage by having cheaper energy in short. And so it’s very difficult without some power that can really enforce decisions over enough leading nations to come up with some solution to that problem.

]]>But what parallels can we draw from the landmark text in a global society?

Through a series of lectures from Dec. 10 to Dec. 15 at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China, Nicholas Tampio, Ph.D., an associate professor of political science, examined Deleuze and Guattari’s pioneering theories through such a political lens.

Tampio, who specializes in the history of political thought, contemporary political theory, and education policy, spoke of Deleuze’s political vision and how it sheds light on think tanks and intercivilizational dialogue.

Xia Ying, a philosophy professor at Tsinghua, invited Tampio to speak at the leading research university founded more than 100 years ago. Stephen Freedman, provost of Fordham University, said many Fordham faculty have scholarly activities with key universities in China—which is an important priority for Fordham.

“For each lecture, I talked for about an hour, and then everyone asked for clarifications or shared their thoughts, for instance, on how to diagram Chinese political thought,” said Tampio, author of Deleuze’s Political Vision (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015).

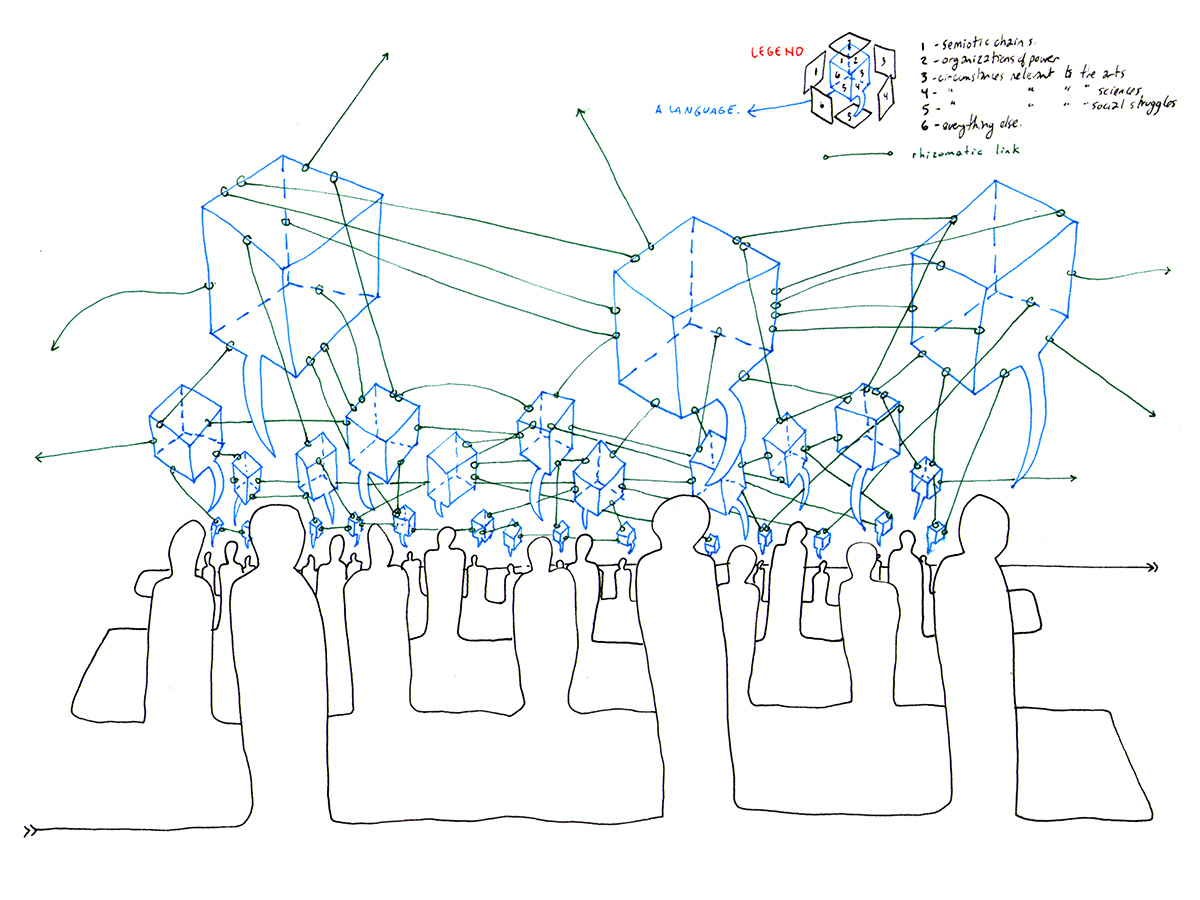

Among Deleuze’s most thought-provoking concepts was his model of the rhizome. Based on the botanical rhizome or “mass of roots” which spreads from a tree, the theory is akin to political multiplicity.

“On one hand, the goal of the lectures was to share my knowledge about Deleuze, but on the other hand, I wanted to discuss the relevance of Deleuze’s ideas in the Chinese context,” said Tampio.

Though China follows capitalistic economic principles and operates as a one-party system, Tampio said he wanted to foster discussions about Deleuze’s philosophical approach amid China’s evolving role in international politics and business.

“It was exciting to see the audience in China thinking about the ideas of the rhizome, and what it would mean to have a multi-polar world where there is no tree trunk of centralized power but where countries have to interact to address shared concerns,” he said.

Tampio, who had never been to China before, said Chinese citizens tend to be more sympathetic to the notion of centralized authority because of their own political system.

“In the West, we have a vibrant public sphere and civil society where people are free to disagree with the government,” he said. “But nearly everyone I met in China spoke English and was interested in talking. China does not have the same tradition of free speech; at the same time, the Chinese I met were curious and open to learning and sharing ideas.”

In the process of sharing knowledge about Deleuzian liberalism, pluralism, and comparative political theory, Tampio said he returned to America with new perspectives.

“China is an economic powerhouse that wants to play a larger role on the world stage, economically and politically,” he said. “We have to take China and Chinese political thought seriously.”

]]>This growing influence was the subject of the Conference on China’s Financial Markets and Growth Rebalancing, held Oct. 2 through Oct. 3 at the Lincoln Center campus and co-sponsored by the Gabelli School of Business.

Keynote speaker Jennifer Carpenter, who is recognized for her groundbreaking research on executive stock options and managerial risk incentives, shared her assessments of the “real value” of China’s stock market— which opened more than two decades ago in Shanghai and Shenzhen and has grown into the world’s second- largest stock market.

“Now China is really ‘required reading’ for any student of sociology and certainly any student of finance,” said Carpenter, an associate professor of finance at New York University’s Stern School of Business.

She noted that China’s stock market is often derided as a “casino” due to speculations of market manipulation and fears that the country may be heading toward a financial crisis. However, her research found that stock prices in China are as informative of future profits as stock prices are in the United States.

“My view is that China is just getting its financial system up to where it needs to be to support a macro economy that is that large and fast growing,” said Carpenter.

Though investors may encounter financial risks related to liquidity and repatriation, Carpenter argued that both Chinese and global investors will likely benefit from China’s decision to open its capital markets.

“In some respects—at least in this context—global investors are having some bargaining power . . . in helping to drive reforms on China’s side,” she said.

The Limits of Autocracy

Conference sessions also examined China’s monetary and macro policy issues. Zhangkai Huang, an associate professor of finance at Tsinghua University, tackled the age-old debate: Are autocracies better at effecting economic policies than democracies?

In his presentation, “The Limits of Autocracy: An Analysis of China’s Renationalization,” Huang provided an overview of how Chinese politicians implement policies in an autocracy.

With a special focus on the dealings of the Shanghai Group, the Youth League Group, and the Princelings— three major political factions in China’s Communist Party—Huang examined the policy of renationalizing previously privatized firms between 1998 and 2007.

Huang defines renationalization as a policy where local governments repossess private shares. He argued that officials who choose privatization may risk upsetting the ruling autocrats before reaping the benefits.

These distortions, he said, might be responsible for China’s “recent stagnation in our market-oriented reforms and the massive build-up of debt.”

Pace University’s Padma Kadiyala, a discussant, questioned Huang’s assessment. She argued that it is premature to conclude that renationalization is an inefficient policy.

“I think the decision should be examined within the context of the legislative framework,” she said before noting that bank lending policies and bankruptcy rates could provide deeper understandings.

“In the absence of a strong legislative framework, maybe renationalization is the only way out.”

The conference was co-organized by the Bank of Finland Institute for Economies in Transition, and the Global Unit at the City University of Hong Kong.

]]>Now, a donation from a Fordham family will help address these issues within the University’s expanding Chinese student community.

The $50,000 gift will go toward hiring a part-time bilingual psychologist to help with issues that are unique—and a few that are not so unique—to Chinese students transitioning to life in New York City. The Lincoln Center-based therapist will be familiar with Chinese culture and provide mental health outreach and clinical services.

The gift was made by family members of a Fordham College at Lincoln Center freshman. The family members, Howie Wang and Toshi Chan, both live in New York City, and understand the challenges facing young Asians in America. Chan, whose parents emigrated from China, grew up on the West coast.

“I’m born here and even I had a difficult transition,” he said. “That experience of trying to fit in has served me well now, but it was pretty difficult at the time.”

Examining Cultural Nuances

Jeffrey Ng, Psy.D., director of Counseling and Psychological Services, said that understanding the nuances of a culture can go a long way in helping students.

“There are many different world views and perspectives on mental health, and lots of variety in the way folks experience and handle emotional distress,” said Ng. “It’s very culturally specific, so it’s helpful to have counselors who have familiarly with the culture and the language.”

Chan was born in a Catholic hospital, went to Catholic grade school, and attended a Jesuit high school. He said that he liked the way Jesuits shared “good ethics” without proselytizing. It’s a quality he thinks will attract Asian students generally.

“They teach modern values without sounding like a preacher,” he said.

When Wang and Chan expressed interest in making a donation, they were given a host of options developed to help Fordham’s growing Chinese community, from interpreting services to cultural training for Fordham staff or an endowed chair in Chinese studies. But the program providing support services attracted them most.

“Asian people tend to keep their problems to themselves and this will be very helpful, because when you’re in a different country you’re even less likely to seek help,” said Chan. “I think it’s great that they’re bilingual because there is a real need.”

Chan, who describes himself as “DACA before there was DACA,” said that the United States still holds a strong attraction for many Chinese students, especially when it comes to education. He said that whether students choose to stay on in the states or whether they return home, the good that will be fostered through studying here lasts a lifetime.

“My family came here for the American Dream and that’s very much alive,” said Chan. “And whether students stay or go back home to do business in China, the more cross-pollinization we have the better it is for both countries.”

]]>In May, Stephen R. Grimm, Ph.D., professor of philosophy, embarked on a trip to China to teach and lecture on his area of expertise—the philosophy of understanding. The trip began as a single invitation to be the 2017 Liu Boming Lecturer in the Philosophy Department at Nanjing University. Xingming Hu, Ph.D., Grimm’s former doctoral student and now a faculty member in the department, made the initial recommendation to his department vice chair, who invited Grimm.

As Grimm had made an impression, Hu, GSAS ’15, also contacted his colleagues specializing in epistemology and teaching philosophy at other top universities in China to see if they would be interested in hosting Grimm as well.

As it turned out, they were.

From one lecture, to eight

“They know of Grimm’s work on understanding, so they were interested in inviting him to give a talk at their home departments,” said Hu of his higher education colleagues.

Grimm’s one engagement grew into eight separate lectures, delivered over the course of a three-week period. He also taught six classes in four different cities and five universities, several of which are among China’s “Ivy League,” the C9 League.

Grimm’s one engagement grew into eight separate lectures, delivered over the course of a three-week period. He also taught six classes in four different cities and five universities, several of which are among China’s “Ivy League,” the C9 League.

Among those philosophy departments that hosted Grimm and promoted his lectures, talks, and workshops, were Nanjing University, Peking University, Renmin University, Xiamen University, and East China Normal University.

Grimm was previously the recipient of a $4.3 million grant that funded a three-year comprehensive study on the nature of human understanding, the largest arts and sciences grant to ever be received by a member of Fordham’s faculty.

He describes his scholarship in the study of understanding as emerging from two questions. First, what does it take to understand the natural world, or some part of it? Second, how does understanding human beings differ from understanding the natural world? Grimm holds that his answer to these questions—that the two types of understanding are quite distinct—is a controversial one in philosophy and the sciences.

“In my view, since human thoughts and desires are structured by values—or what we care about—this makes grasping or understanding other human beings more complex than understanding the natural world,” said Grimm. “In some sense, we need to take on the perspective of other human beings—their cares and concerns—if we want to understand them. And this sort of ‘perspective taking’ is simply not needed when it comes to understanding physical systems involving atoms or stars, for example.”

Though most of his lectures in China focused on understanding, Grimm also had the opportunity to teach six two-hour classes to a group of 14 undergraduate students at Nanjing. The course, “Philosophy as a Way of Life,” was on a theme that Grimm has previously taught to undergraduates at Fordham.

A curiosity about other cultures

Though the English-language expertise of the Chinese students varied, Grimm said they were “clearly insightful about the material, and had a deep desire to engage with Western philosophy.”

“They were deeply curious to learn about other cultures,” said Grimm. “And very optimistic about the future.” Such optimism, he said, is not as common among 21st-century Americans.

In the end, Grimm said his main takeaways from the trip were both cultural and professional, citing a gained appreciation for Chinese culture and new relationships with Chinese scholars, which he hopes to continue in the future.

“One of my goals is to host an annual conference in New York that will bring together Chinese and American epistemologists, to exchange ideas about our work,” said Grimm. “The Chinese philosophers to whom I suggested this idea were extremely enthusiastic about it, and I am sure I can generate enthusiasm in the idea among U.S. philosophers too.

“Such an exchange would help to put Fordham on the map of Chinese students and professors, which would be a boon to Fordham’s international reputation.”

—Rebecca Sinski, FCRH ’17

]]>Niu, who graduated last year with a master’s degree in global finance, is one of 31 students to have received a Schwarzman Scholarship, established in 2013 by a foundation started by Blackstone Group CEO Stephen A. Schwarzman. She is Fordham’s first Schwarzman scholar.

In August, she will enroll at Schwarzman College, a new institution that is part of Beijing’s prestigious Tsinghua University, with the goal of earning a master’s degree in global affairs.

Niu, who is living in Shanghai and working with the social entrepreneurship competition “China Thinks Big,” called the opportunity a “dream come true.” She said working in international affairs has long been her goal, and having interned in United Nations’ Regional Commissions New York Office, she was considering another internship at the United Nations when she received word that she’d won a Schwarzman Scholarship.

“I was attracted by its vision of ‘global leadership for the 21st century.’ As an international student who has studied and worked in New York City, I feel connected to this global vision,” she said.

Niu also said she hopes that studying at Tsinghua—which counts among its alumni many of China’s top political and business leaders—will help her understand her home country.

“I see myself as the product of both the Chinese and U.S. educational systems, having spent my high school and college years in China and then the majority of my post high-school years in the states,” she said.

Rob Garris, global director of admissions for the Schwarzman Foundation, said its hope is that the knowledge and relationships that students such as Niu develop during their time at Schwarzman College will bear fruit decades later.

“What we’re trying to do is ensure that all around the world, the next group of business, political, and nonprofit leaders have a deep knowledge of China and the role that it is playing in the world, and have strong professional contacts with their peers there,” he said.

“When they become leaders, they can use their positions to help ensure there is a good flow of information between China and the rest of the world, and that relationships are peaceful and prosperous.”

Garris said that Schwarzman scholars were chosen based on their having demonstrated initiative, an ability to recruit others to sign onto their projects, and a record of persisting in the face of obstacles.

“Creating change in any sort of system, whether it’s a political system, a business system, or the nonprofit world, is always going to encounter resistance,” he said. “So we ask candidates to give us tangible examples of when they’ve encountered that resistance, solved it, and pushed past it.”

Currently in her fifth year of working for the Harvard College Association for U.S.-China Relations, Niu has played a leadership role in designing content that promotes transitional dialogue between young leaders of China and the United States. She interned at the U.N. Regional Commissions New York Office, under the Economic and Social Council.

She said her long-term aspiration is to build incubators that enhance culture and business exchanges among countries, a goal that has been made possible from her time at Fordham. Gabelli School of Business adjunct professor Anthony Palma, and Fordham School of Law adjunct professor Carole L. Basri helped her apply for the scholarship, and living in New York City provided opportunities to listen and learn from influential industry leaders.

]]>This past January, GSS formed an additional partnership with the Beijing University of Technology.

Under the new partnership, students from CYU will earn a bachelor’s in social work from Fordham and, should they choose, would also continue on for a master’s. Fordham students get a summertime opportunity in China where they can choose between two three-credit courses while becoming familiar with the culture.

they choose, would also continue on for a master’s. Fordham students get a summertime opportunity in China where they can choose between two three-credit courses while becoming familiar with the culture.

“It’s about bringing Chinese students to experience one of the most vibrant cities in the world and learn professional skills at Fordham that they can bring back home to have a positive effect,” Debra McPhee, PhD, dean of GSS.

After the Cultural Revolution, social work practice was not permitted in China, said David Koch, PhD, associate professor and director of the bachelor’s degree program in social work. He said that it was only in the 1990s that social work practice began to be taught again at universities.

“Like anywhere in the world, China’s families and culture are being taxed by social and economic realities that present a great many challenges, particularly in urban areas,” said McPhee.

Over the next 20 years China will need to employ approximately 2 million social workers to deal with the needs of a massive population and an “explosion in urban economy,” she said.

Koch, who taught at the last two summer sessions at CYU, said that while Beijing’s population of 21 million may impress, it pales in comparison to the megacity that the government plans to link together with bullet trains over the next decades.

“Beijing will be at the center of 130 million people, and that will affect how services are delivered,” he said. “That environment will require a different kind of practitioner. We’re helping to develop that.”

“We want to help China increase its effectiveness in helping people,” he said. “And in site visits with CYU and Fordham students, we really see what’s happening on the ground; it’s not just the 30,000-foot view.”

Koch said the local governments are far more forthcoming than in the past in revealing and confronting issues such as HIV, undersupervised migrant youth, and care for the elderly. Such a shift will be beneficial, especially on the growing professionalization of social work.

“What we’re seeing in the universities is an attentiveness to what social work can give them, something which in the past they couldn’t utilize,” he said.

“In these kind of partnerships there’s always a benefit on both sides,” said McPhee. “It’s about building bridges.”

There will be several information sessions in March for Fordham students interested in taking a three credit course in Beijing. For more information contact David Koch at [email protected].

]]>“I didn’t have that many opportunities myself, so I know firsthand that if we provide education and opportunities for disadvantaged kids, it will make a difference in their lives,” he said.

Whether the cohort is underserved communities of New York City or rural-to-urban migrant families in China, Zhai provides quantitative analysis of survey data in the hopes of affecting policy.

Most of his research has focused on disadvantaged children in the United States. However, the native of China has begun to delve into childcare and education issues in his home country with a focus on migrant workers in Beijing.

He has been working with researchers from five universities in Beijing to collect data on family resources, migration experiences, and parents’ views on traditional values, child rearing, and education practices. He is also gathering data on children’s school experiences and developmental outcomes.Zhai described a country in the midst of extraordinary transformation, but still rooted in some ancient traditions, such as Confucianism, which fosters a preference for sons in a family. He said that traditionally boys, especially eldest sons, have been given more opportunities to succeed. China’s former one-child policy has further influenced the preference.

The one-child policy was implemented differently across the urban-rural divide, with cities strictly enforcing the policy and many rural areas allowed more than one child, especially if the first one was a girl.

Even though the recent phase-out of the one-child policy will free couples from the pressure to have sons, Zhai’s research shows that boys will still be favored compared to their female siblings when it comes to education and opportunities.

Part of the reason, he said, is because China doesn’t have an established pension system; instead the country still largely relies on traditional values where children, especially the eldest son and his spouse, take care of their parents in old age.

“It’s very complicated to shift from the traditional values to a new system,” said Zhai. “That’s why I want to see through data if girls are discriminated of investment in their education and if they are at a disadvantage.”

Zhai’s work also examines the effects of the country’s urban vs. rural services. In the planned economy, urban residents were provided with better services than rural residents, including child education, he said. Even today, Chinese citizens must register with the government as an urban or rural household status.

China’s “Rural” Status

Even as millions of rural residents move to the cities for better opportunities, their “rural” household registration status stands, thereby preventing their children from participating in the city’s formal school system.

“The parents can’t receive several social benefits and their kids can’t go to the public schools,” said Zhai. “It’s a huge problem.”

He said that many of the “rural” migrant communities that live in the cities have started informal schools, but most teachers don’t have proper training. And the problem may intensify, as many expect there to be a baby boom over the next decades now that the one-child policy has lifted.

Zhai said that there are a lot of efforts in China being undertaken to reform the system, and he hopes that his studies will provide solid evidence from data analysis supporting more change.

“The good part of being an outsider is that I can see the system from afar and analyze objectively,” said Zhai.

“But the truth is I know this from both sides, inside and out.”

]]>But while the country has embraced economic freedom, democratic reforms there have not fared well, and in recent years, the ruling Communist Party has clamped down hard on dissent. Tom De Luca, PhD, professor of political science, says that the hope for democracy has been set back in other parts of the world as well, such as in post-Soviet Russia, and post-Arab Spring Egypt.

“The idea some argued when calling for China’s entry into the World Trade Organization was that with the development of capitalism, you would develop more of a middle class, which then would make demands on the system for more openness and more political freedom. “Unfortunately, real political freedom just hasn’t happened in China,” he said.

De Luca is uniquely qualified to assess the fits and starts of the democratic process in East Asia. He first visited the country on a Fulbright fellowship in 1999 when he taught a class there on U.S. Constitutional Law, and has returned every year since, for the last nine years with Fordham students as part of his class, China and the U.S. in the Era of Globalization. The course will be offered again next spring.

In 2005, the country was open enough that De Luca was able to organize, with colleagues at China University of Political Science and Law, a conference on constitutionalism and democracy in China. In a prelude for the backlash to come, it was canceled by authorities at the last minute. Undeterred, he moved it instead to the sanctuary of the Netherlands embassy in Beijing. He attributes the growing intolerance for dissent, in part, to a deep fear of social instability that is an effect of China’s incredibly rapid change.

“A lot of people don’t know this, but China has probably 100,000 demonstrations a year. The government documents these things and its known among people who study this,” he said.

“A lot of times, it’s very local stuff. You know, they took my land to build this factory, and I was supposed to get a certain amount of compensation and it hasn’t come,” he said.

The theory and practice of democracy in the United States and abroad have formed the basis of De Luca’s scholarship. Most recently, he co-authored The Democratic Debate: American Politics in an Age of Change (Cengage Learning, 2015), now in its sixth edition.

In China, the biggest test of whether economic and political liberalization can co-exist is in Hong Kong, where leaders recently rejected a proposal by the Communist party to allow citizens to choose their leader from a slate of candidates chosen, in effect, by the party.

“Beijing has to be careful, because they can’t use the kind of extremely heavy hand that they used in Tiananmen Square in 1989. I’m not saying in the end they wouldn’t, but they have to be careful, because it would be very economically harmful to China to have that kind of confrontation now,” said De Luca, who also heads Fordham’s International Studies program at Lincoln Center.

Democracy is not unheard of in the region, of course, and De Luca notes that for every Singapore, which is economically vibrant but not democratic, there are democracies in South Korea, Japan and Taiwan. And students learn a lot just by visiting Beijing and Guangzhou (old Canton), where they live for about a week with students at Sun Yat-sen University.

“First it’s observing; how is Guangzhou different from New York or even from Beijing? But then when they’re with the Chinese kids, then it’s really a matter of talking about their lives, and that inevitably brings comparisons; you know, ‘What’s my life like, what’s your life like?’ They often make a friend or more than one friend,” he said.

Democracy isn’t fading as a model for the world, but it is in danger of losing its luster, he said, thanks to the demonization and vitriol in American politics that’s made it so difficult for our political system to look efficient.

“It’s a question for some people: Is that really a model that would work for us? So I worry about that a little. I do think still that democracy is far and away the most appealing philosophy as how to organize a society. I don’t have any doubt about that, but I do think that democracy’s not in everyone’s interest, and people will push back against it,” he said.

“We saw that in Egypt, where the president who was elected is essentially on trial for his life. It moved very quickly back to a military dictatorship. But you know, that’s how history is. History moves in its own way, so that doesn’t mean that’s the end of the story.”

]]>