BJHP is a Fordham research initiative that preserves the stories of the Jewish Bronx. The project originally began with Sophia Maier, FCRH ’23, who documented the stories of more than 75 members of the Jewish community who once called the Bronx their home. Now, in the months before Maier earns her master’s degree in teaching from the University this spring, she’s teaching a new group of undergraduates how to continue the project.

Oral History with a Professional Historian

About a dozen undergraduate and graduate students joined BJHP this semester, thanks to an Arts and Sciences Deans’ Faculty Challenge Grant. The students, who study subjects from economics to theology to history, are interested in BJHP for different reasons, said Daniel Soyer, Ph.D., BJHP director and history professor. Some are Jewish themselves, with family ties to the Bronx. Others are interested in Jewish studies and history.

During a recent training session, the students met Leyla Vural, a New York City-based oral historian. Vural, who has a master’s degree in oral history from Columbia University, has interviewed recipients of the Nobel Prize, scientists, artists, trade unionists, LGBTQ New Yorkers, and more. She spoke with the students about how to approach their interviews and navigate the ethics of their work.

“What stuck with me most was when she talked about how the role of the interviewer was, above all, to listen,” Maier said.

Jews in the Bronx: An Important Part of NYC History

In another session, Soyer taught students about the history of the Jewish Bronx.

“The Bronx was once the most Jewish borough—almost half Jewish—and now it’s the least,” said Soyer. “Through [BJHP], we’re capturing an important part of Bronx, New York, and Jewish history that’s been understudied.”

As part of their training, the students also learned from Maier about how to conduct interviews, using a 27-page guidebook developed by Maier herself.

“I’m considering going for my Ph.D., so it’s great to get that experience, working with undergraduates,” said Maier, an aspiring history teacher who earned her bachelor’s degree in history from Fordham College at Rose Hill and is now part of the accelerated master’s degree program at the Graduate School of Education.

This summer, Maier, Stovall, and Soyer will teach high schoolers about the history of Jews in New York in a weeklong course, part of Fordham’s annual summer programming. Their curriculum will include oral histories from BJHP, said Soyer.

Having a Cup of Tea and ‘Just Listening’

Being a part of BJHP means so much, said Maier, who teared up while speaking.

“It’s changed the trajectory of my life. I love doing it, and I’ve met so many amazing people. … These people are predominantly elderly, and they really appreciate that some young person is taking an hour or two out of their day to sit down, have a cup of tea with them … and just listen,” said Maier, noting that the oldest person she has spoken with is 97. “To have their life stories recorded and made available [especially for their families]is a gift without value.”

]]>For Sophia Maier, a senior at Fordham College at Rose Hill, interest in Bronx Jewish history was sparked when she interviewed her grandparents about their upbringing for a Bronx history course at Fordham.

“I said, ‘all right, well this is really important,’” she said. “So I did my thesis on doing oral history interviews with folks who grew up in the Bronx and left during the period of white flight in the 60s and 70s and into the 80s.”

She added that her research, which included interviews with more than 40 community member so far, focused mainly “on the 40s, 50s, and into the early 60s—a lot of those folks are people whose grandparents immigrated to this country, typically from Eastern Europe.”

“Since they came into this country, there has been this sort of upward movement—both geographically and on a class basis, starting out on the Lower East Side, or Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in this kind of crowded tenement living, [and then]folks moved up to the South Bronx, or then further up into the Northwest Bronx.”

Maier and Reyna Stovall, a sophomore at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, shared their research on March 1 at “Jews in the Bronx: Archival and Oral Histories,” an event hosted by Center for Jewish Studies. They were joined by Daniel Soyer, Ph.D., professor of history; Ayala Fader, professor of anthropology; and Ayelet Brinn, Ph.D., the Philip D. Feltman assistant professor of modern Jewish history at the University of Hartford who did postdoctoral research at Fordham.

The students’ work is at the heart of a new initiative of the Center—the Bronx Jewish History Project, which was publicly launched at the event. Maier’s interviews, paired with Stovall’s archival research, are the basis for the project, Sarit Kattan Gribetz, Ph.D., associate professor in the theology department, said. It was also partially inspired by the Bronx African American History Project, which was founded by Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of African and African American studies.

Magda Teter, Shvidler Chair of Judaic Studies and co-director of the Center for Jewish Studies, helped introduce and combine the students’ work into a larger project that will live beyond their time at Fordham, Gribetz said.

“Through our new initiatives at the Center for Jewish Studies, we’re collaborating across generations and fields to collect, preserve, share, and learn from these stories,” Gribetz said.

Piecing Together History

Stovall came to Fordham from San Antonio, Texas, and didn’t have any connection to the Bronx. Working for the Holocaust Museum in Texas piqued her interest in Jewish Studies though, so she minored in it at Fordham, and met Teter.

“I met Dr. Teter, who said, “Oh, we just got these new interesting documents from the Jewish Bronx, and I thought, ‘The Jewish Bronx? I thought the Jews lived in Brooklyn,’” Stovall, who is Jewish, said with a laugh. “I wasn’t aware of the significance of the Bronx to Jewish history.”

She began interning with the center last semester and began “deep diving into all of these archives that we started acquiring.” In the spring of 2020, the center hosted a virtual event called “Remnants: Photographs of the Jewish Bronx.”

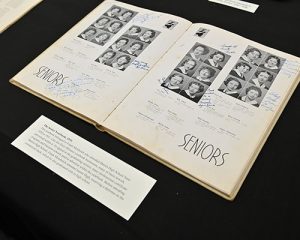

Ellen Meshnick Immerman, who grew up in New York, attended, and was so inspired by the event that she donated material, including everything from yearbooks to bar mitzvah invitations from her parents, Frank and Martha Meshnick, who had grown up in the Bronx.

“Looking at them was absolutely fascinating to me—getting to know people’s stories through the little bits and pieces of their lives,” Stovall said.

The Meshnick’s documents “really opened my eyes to how special the Bronx is,” she said.

Stovall also spoke with Meshnick Immerman, and the conversation elevated the work to a new level, she said.

“I had this vision of what their life was like in my head, but getting to talk to her, I got to know more the feelings that were associated with it—how her mother put so much pride in her appearance, how they went to these stores to prepare for these certain things for their Shabbat days, just things like that that showed me the dimensions of history.”

Capturing Untold Stories

Maier’s project started with interviews with her grandparents, and is rooted in oral histories. She’s conducted more than 40 interviews so far, with “more coming everyday,” including one scheduled in a few days with a Bronx resident who survived the Holocaust.

She found that Jewish people, particularly those in the South Bronx through the 40s, 50s, and 60s, lived in “really diverse neighborhoods and environments” where they felt “secure” and like they were a part of a larger community.

“People were like, ‘Oh, I never locked my door,’ or ‘My Italian neighbor across the street, she’d always give me cookies when I came home,’—things like that, that kind of captures the sentiments of how people were feeling,” she said.

Residents described how schools were integrated, although there were tactics employed to keep many of the white students in classrooms separate from the Black students. But many said their diverse, public education was at the heart of the upward mobility they were able to achieve.

“For a lot of the people that I spoke to, their parents were kind of manual laborers, truck drivers, small business owners, factory workers. But because of the great public education that they got and continued for college education, a lot of them were teachers and doctors of various kinds.”

Many Jewish people left the Bronx, Maier said, as a part of their “striving toward this solid middle class standard of life,” which included wanting more space for their families and being able to afford the suburbs. But interviewees also told her their families left because “the Bronx was changing.’ At that time, many Black and Hispanic residents were moving into the Bronx, and many Jews people moved out.

“Leaving the Bronx for a lot of Jews, meant leaving this distinctly Jewish place—you didn’t have to be a religious Jew to be a Jew in the Bronx,” she said.

Tying the Stories to the Artifacts

Stovall said that she believes this marriage of archival material with oral histories is what makes the Bronx Jewish History Project so unique.

“I get to see both sides of history—the emotions and feelings that are associated with the Bronx, but also the archival materials,” Stovall said, adding that the project will carry a record of their history forward.

Learn more about the Bronx Jewish History project and other initiatives taking place at the Center for Jewish Studies.

]]>Today, the program, which is jointly run by Fordham, the American Academy for Jewish Research, and the New York Public Library, continues to support these scholars, many of whom had to flee their homeland.

When the program was conceived, Fordham offered a year-long fellowship to a student pursuing master’s level studies in the area of Jewish and Slavic studies. The others, a mix of Ph.D. students and scholars working in the same area, were provided stipends, access to electronic resources at Fordham and the library, and invitations to five remote workshops.

Magda Teter, Fordham’s Shvider Chair in Judaic Studies and an administrator of the program, said the program will help scholars document this period in history. She said a source of inspiration for the project was the work of Samuel Kassow, who wrote about the efforts to document the experience of living in the Warsaw ghetto during the Holocaust in his 2007 book Who Will Write our History? (Indiana University Press, 2007).

“I think it is important for the moment to gather, to collect, to preserve, to remember,” she said.

“It is our duty to help these scholars in any way we can. Even small stipends mean a lot to them when their institutions have been bombed or are inaccessible.”

Working Even When the Lights Go Out

When Tetyana Batanova delivered the lecture “Yiddish Sources and Resources: My Personal Path to Jewish and Yiddish Studies” virtually from her apartment in Kyiv in the lecture series “Scholars at War” on April 8, it was a welcome splinter of normalcy. Russian armed forces, which had occupied her Kyiv suburb of Bucha in the opening month of the war, had only retreated from the area a week earlier.

Batanova, the acting head of the Judaica Department at the V. Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine, had been conducting research for her dissertation about the five Jewish political parties that participated in Ukraine’s national government in 1917-1918. At the time, Yiddish was one of four officially recognized languages in the country. Today only Ukrainian is officially recognized by the government.

With her country facing an existential crisis, Batanova said she had serious doubts about the importance of her research. The fellowship has helped restore her faith.

“Seven months later, I’m more confident in what we do, and that we should continue,” she said.

“But in April, it was not that obvious for me at all. When I was invited to give my lecture, it was good that it was in April, because in March I was not able to speak at all.”

Historical research is only as good as the original sources one can acquire, and having worked at the New York Public Library in 2006, Batanova knew what kinds of archival documents and journal articles she’d need. As a result of the fellowship program workshops, she was able to access new books from Fordham University Library online resources providing the context for her research, such as Stephen Velychenko’s book Life and Death in Revolutionary Ukraine : Living Conditions, Violence, and Demographic Catastrophe, 1917-1923 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021).

Her research focuses a great deal on Yiddish, a language intrinsically tied to the Holocaust and its victims. It was also the primary language of the 30,000 to 70,000 killed in anti-Jewish pogroms that swept Ukraine in 1919.

Although it is still spoken in pockets around the world, its importance is not widely known, making it an ideal path for the average citizen to learn about Ukrainian history, Batanova said.

“The story of Yiddish is quite similar to the story of Ukraine in the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.”

Fleeing War for NYC

Andrii Pykalo was just beginning his graduate studies when the war began. He attended V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, in Kharkiv, the country’s second-largest city just 25 miles from the Russian border. Feb. 24, the day that Russia attacked, will forever be cemented in his mind.

“I will never forget the sky over my neighborhood. It was yellow, because of all the Russian rockets,” he said.

“It was very, very noisy, and I remember the panic. It was a horrible surprise for all.”

Continued study in Kharkiv was never an option; for starters, the university library was hit by a Russian missile. Pykalo said he tried to help save some of the books from the collapsed structure.

He had to jump through numerous bureaucratic hoops to leave, but he was granted permission in May, and he arrived in New York City to attend Fordham on Aug. 23. He has been living in an off-campus apartment in Harlem and attending classes, such as one on antisemitism with Teter and another one about advanced research methods by history professor Grace Chen, Ph.D.

For his research project, “Soviet Jews and the History and Memory of the Holocaust in Ukraine,” he’s been able to use his time in New York to locate documents that show how Americans viewed Jews in the Soviet Union at that time.

Apps such as Telegram and WhatsApp have made it possible for Pykalo to stay in touch with his friends and family, and he’s also connected with the Ukrainian diaspora in the East Village. But the decision to leave Ukraine was a fraught one.

“I understood that I should have been in Ukraine defending my country. I should be with my family, I should be with my friends,” he said.

“I was really afraid for my family, but they all told me that I must go because it’s my profession. This is my task.”

Seeking Safety in Michigan

Yurii Kaparulin, Ph.D., an associate professor of history and legal scholar at Kherson State University in southern Ukraine, found himself on the wrong side of the border when war broke out. While his wife and son were home in the city of Kherson, he was in Bucharest, Romania. His family spent a month in Kherson while it was occupied by Russian forces before they were able to evacuate and reunite. In August, they moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where Kaparulin received a separate, “scholars at risk” fellowship from the University of Michigan’s Weiser Center for Europe and Eurasia.

For Kaparulin, the Fordham fellowship, which he was offered after moving to Ann Arbor, has been invaluable for the completion of his book, “Between Soviet Modernization and the Holocaust: Jewish Agrarian Settlements in the Southern Ukraine (1924-1948),” which he began seven years ago.

The war forced him to leave behind some of his own research, but more importantly, he lost access to his own university’s archives.

“Before Russian troops left Kherson, they looted the biggest part of the Kherson State archive. So I needed to figure out where I would look for sources and get some of the newest articles and books,” he said.

Through the Fordham fellowship, he’s been able to access resources such as the article Farming the red land: Jewish agricultural colonization and local Soviet power, 1924-1941 Jonathan L. Dekel-Chen, (Yale University Press, 2015), and “Men inspecting foals at an artel supported by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Kherson, Ukraine” a black and white photo from 1924.

His project addresses mass violence and wartime collaborators from the past–both of which have ties to the present. One of the reasons why Russian President Vladimir Putin has smeared Ukrainians as Nazis, he said, is because there were, in fact, Ukraine citizens who collaborated with the Nazi regime during World War II.

However, Russian propaganda effectively ignores the contribution of millions of Ukrainians to the victory over Nazism, he said. That is, when it comes to examples of collaborationism, the Ukrainian origin of the accused is emphasized, he said, and when it comes to heroism and victory, “Soviet heroes” are mentioned without ethnic context.

The phenomenon of collaborationism has also been observed during Russia’s current war against Ukraine. For example, during the occupation of Kherson from March to November 2022, some residents cooperated with the Russian occupiers.

“Their motives are currently being established by law enforcement agencies. However, in general, we see that the majority of the city’s residents have maintained the Ukrainian position despite various risks, including to their lives,” he said.

Providing Tools for Research

To help the scholars with their research, Shawn Hill, an instructional technologist in Fordham’s department of informational technology, delivered a workshop in November that walked participants through the reference tool Zotero. The bibliographic and citation tool makes it easier for scholars to organize papers, monographs, books, and articles.

He also demonstrated Art Steps, a tool used by interior designers, art historians, and gallery managers to create virtual exhibits.

“You may have a painting in Kyiv, a sculpture in Kharkiv, and something in Odesa. You can’t bring them together in the real world for obvious reasons, but you can create an Art Steps exhibition space and give the URL to a guest or a friend or the public as a whole.”

My Soul Is Still There

Lyudmila Sholokhova, Ph.D., Curator of the Dorot Jewish Collection at the New York Public Library, grew up in Kyiv, and like Batanova, she worked at the V. Vernadsky National Library before moving to the United States.

In 1997, she was the recipient of a fellowship and spent time at the United States Library of Congress. Now she’s the point person for the fellows in the program working with New York Public Library.

The fact that she’s able to now help other scholars from Ukraine moves her deeply. “My soul is still there. I want to help my people in any way possible. I want to support them,” she said.

“I know the value of access to all these enormous resources that these libraries can provide. When I was in Ukraine, I had access to the primary sources, but I didn’t have access to scholarship on the documents,” she said.

“When you work on this subject, you really need the context. You really need access to a much larger corpus of resources.”

]]>This was the challenge that a panel of experts—together with one Holocaust survivor—addressed at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus on Jan. 26.

The event, “Remembering: Talking About the Holocaust in the 21st Century,” took place on the eve of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which commemorates the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp on Jan. 27, 1945.

Fred de Sam Lazaro, a correspondent for PBS NewsHour and director of the University of St. Thomas’ Under-Told Stories Project, moderated the evening, along with Peter Osnos, founder of PublicAffairs Books.

The discussion began with a screening of de Sam Lazaro’s 2022 PBS NewsHour segment on Nicky & Vera: A Quiet Hero of the Holocaust and the Children He Rescued (Norton Young Readers, 2021). Written and illustrated by Peter Sís, who was in the audience at the Jan. 26 event, it tells the story of Nicholas Winton, known as the “British Schindler,” who helped 669 children escape from Czechoslovakia just before the Nazi occupation.

One of ‘Winton’s Children’ Shares Her Story

One of those escapees, Eva Paddock, was interviewed by de Sam Lazaro at the event. She spoke just before the panel of experts addressed diminishing public awareness of the Holocaust amid a rise in disinformation and revisionism. In 1939, when she was 4, Paddock and her sister were placed by their parents on the last Kindertransport train leaving Prague and taken in by a foster family in England. Unlike the majority of “Winton’s children,” as they came to be known, Paddock was reunited with her parents in 1940.

Because she was so young, she needed people like her parents to help her fill in the gaps in her memory, she said. When they talked about their experiences, they did not dwell on the evil that drove them from their home, but on the gratitude they felt toward the British people.

She also shared the harrowing details of her father’s escape, which was made possible only because of the altruism of individuals, from an S.S. officer who looked the other way when he encountered him, to a stranger who paid for his flight from Brussels to London when he was told his Czechoslovakian money was no good with the country in enemy hands.

Educating Young People About the Holocaust

Holocaust education, which is mandated in schools in only 27 U.S. states, is due for a change, and her and her father’s stories should be a part of that change, Paddock said. Both stories show how even a single person has the potential to do enormous good.

“It has to come out of the history books and be made relevant to today’s generation, and I believe the way to do that is to reframe the way it’s taught,” she said.

“Certainly, it’s important to teach [people] to honor the millions lost, but I think it needs to be reframed to demonstrate the power of altruism and the power of one. Because of course, I look at Nicholas Winton, and here’s a prime example of the power of one.”

The panel that followed featured Judy Woodruff, senior correspondent, PBS NewsHour; Magda Teter, Ph.D., the Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies at Fordham; James Loeffler, Ph.D., the Jay Berkowitz Professor of Jewish History at the University of Virginia; and Linda Kinstler, author of Come to This Court and Cry: How the Holocaust Ends (PublicAffairs, 2022).

Their wide-ranging conversation touched on everything from the war in Ukraine and the 2017 “Unite the Right” white supremacist rally at the University of Virginia to the challenges faced by U.S. news organizations when newsworthy politicians use extreme rhetoric that was once beyond the pale.

Building a Framework for Memories

Loeffler said that when it comes to sustaining the memory of the Holocaust, it helps to remember that many people are involved—each with a different memory. This partly explains why Russian president Vladimir Putin could make the preposterous statement that Russia was invading Ukraine to fight Nazis and fascism, he said.

“One of our challenges is to build a frame so we can build an ethical response that takes the memory and brings people back together to understand what it was and what it wasn’t,” he said, noting that Paddock’s experience is instructive.

“When she was describing her own experience … she also talked about how her memory had been nursed and supplemented by people explaining to her her experience, describing things that had happened to her family and to her when she didn’t even remember,” he said.

“Memory is not just an individual flame that we nourish. It’s a social endeavor, and one of our challenges today is to figure out how we can rebuild that frame to make Holocaust memory relevant, and also build a common understanding of the past.”

Teaching About Events Leading to the Holocaust

Teter said that discussions with her students have convinced her that it might be better to place more emphasis than in the past on the lead-up to the events of the Holocaust. It’s something she does already and feels strongly about its value.

“That is what makes it relevant because they can see the processes, they can see the mental frameworks, they can see the media environment, the propaganda work that resonates with them, and the world that they are living in,” she said.

“It doesn’t just spring up in 1933. This is an outcome of a longer process. We need to recalibrate that story to include that longer story too.”

Unreliable News Sources with a Platform

Complicating the effort to recalibrate the way that the Holocaust is taught is the fact that those who would muddy the waters with obfuscation and ambiguity have access to more communications tools than in the past. Woodruff said journalists at NewsHour have had to come up with a new construct over the last several years to cope with the shattering of the traditional news delivery model.

“How do you both cover the news, be fair, cover it all, and call out something that is not the truth, that is a lie? I will tell you flat out, I’ve had difficulty with that,” she said, because she believes you cannot call someone a liar unless you know what’s in their heart and mind, an admittedly tricky endeavor.

She and her colleagues have adjusted by explicitly labeling false information as such. But given the plethora of news sources available online now, more responsibility has fallen on us as individual consumers.

“There’s a much larger burden placed on news consumers to figure out, ‘Can I trust this, can I believe this? How do I know?’ she said.

“We’re living in a much more complex, complicated moment when it comes to understanding what to believe.”

The event, which was livestreamed, can be viewed in its entirety below.

]]>The new research room will be a space for future art exhibitions and will serve as a seminar room for small talks and presentations once the proper technology is installed.

Miller, who graduated from Fordham College at Rose Hill in 1968 and is a University trustee, said he had a very positive experience with Jesuit education as a Jewish student.

“I was a poor Jewish kid from Liberty, New York, and Fordham provided financial aid that allowed me to attend college,” said Miller, who has been a great supporter of the center since its inception. “I had a lot of Catholic friends and neighbors, so I wasn’t intimidated by the atmosphere of a Jesuit campus.”

He said he got a great education and became a believer in Jesuit education, particularly the “concept of cura personalis and teaching students how to think.” He has always found the Jesuit approach to theology and philosophy to be inclusive and open-minded, he said, though up until recently, there was nothing resembling the Jewish Studies program at Fordham. He tipped his hat to Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president emeritus of Fordham, and “our Jewish provost [the late]Stephen Freedman, a blessed memory” for supporting the inception of the center along with Eugene Shvidler, GABELLI ’92. Shvidler endowed a chair in Judaic studies held by the center’s co-director Magda Teter, Ph.D. Sarit Kattan Gribetz, Ph.D., also co-director of the center, acted as the evening’s host.

“In a very short time—especially by university standards—Magda’s insight and hard work have created a fantastic program that stands out for its bold approach,” Miller said.

He added that antisemitism has become rampant on campuses throughout the world, underscoring the need for a program that “bridges cultures, religions, and even races to help everyone gain understanding.” It’s what made him want to give to the program in the Jewish tradition of tikkun olam, often translated as “repair the world,” which he said is perhaps best embodied in a poem by Alberto Ríos.

“We give because someone gave to us. We give because nobody gave to us,” Miller said, quoting the poem, before being overcome with emotion on reading the next line. “We give because giving has changed us. We give because giving could have changed us.”

Miller was followed by Tania Tetlow, president of Fordham, who described herself jokingly as “a wannabe Jew” and told the crowd of her time singing in the choir of a New Orleans synagogue. She said she had not missed the high holy days for 20 years.

“I’ve understood how deeply intertwined Judaism and Catholicism are… and the connections we have of the deep intellectualism of both faiths, of the desire to study text and the interpretation of text going back for thousands of years, of the love of ritual,” she said, before adding to much laughter, “and the central place of food and guilt.”

To mark the occasion, a photo exhibition was hung in the research room; it’s titled “Jewish Remnants in the Bronx: Photographs by Julian Voloj.” At the reception, Voloj’s black and white contemporary photos, a few of which portrayed a layered history of Pentecostal churches housed in old synagogues, were hung above tables displaying a local Jewish family’s photos and records that were culled from the library’s archives and curated by Jewish studies minor Reyna Stovall, a sophomore at Fordham College at Lincoln Center. She said that working on the exhibit helped her appreciate the Bronx and its history.

“History teaches us so much about life and troubles and prosperity,” said Stovall. “History can teach us so much about not only the past, but about ourselves, and the future we want to create.

Following the program, Rabbi Yigal Sklarin of the Yeshiva of Flatbush offered a blessing for the room. Miller hung a mezuzah on the doorframe of the room that now bears his name.

“The mezuzah highlights the ability of the individual to sanctify the private spaces we inhabit: a belief in the capability of the individual to elevate their surroundings and uniquely infuse them with holiness and meaning,” said Rabbi Sklarin. “But the mezuzah also serves as a reminder as we leave the private and emerge into the public sphere. It is our role to take this holiness and meaning and share it with the world at large.”

]]>

Kim Bepler, a Fordham trustee fellow, is providing a dollar-for-dollar match for all donations to the new Fordham Ukraine Crisis Student Support Fund, up to $50,000. The fund will be used for essential needs such as meals, housing, emergency health care, travel funding, tuition assistance, and more.

It is meant to help roughly a dozen Fordham students from the two countries whose finances, and lives, may have been disrupted because of the conflict. A few of those students have already sought help from the University, and more are expected to do so.

Bepler said she offered the funding as a way to help Fordham students who have lost not only their funding sources but also their sense of certainty and stability.

“I feel strongly about the situation, especially [because of]the students and how vulnerable they must feel when they have no access to their family and they don’t know what’s going to happen to them next,” she said. “It’s not fair.”

The war has caused anguish and a sense of helplessness for some Fordham students who have family members in Ukraine who are caught up in the conflict. It has prompted rallies and discussions in the University community, as well as a fellowship program cosponsored by Fordham’s Center for Jewish Studies to help Ukrainian scholars carry on with their work, despite the conflict.

The Russian invasion has caused $565 billion in economic losses in Ukraine, one of its government ministers said on March 28, and more than 4 million refugees have fled Ukraine since the start of the invasion, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Russian students are vulnerable too, as financial freezes in response to the Russian invasion can keep Russian families from supporting their students in the U.S. These young people may also be impacted emotionally by the backlash that Russians around the world are facing due to Putin’s actions. Bepler expressed hope that Russian students would not feel burdened or isolated by an action begun by the Russian president.

“This is symbolic of defending democracy against a madman,” she said. “In response to the madman, we’re going with magis,” she said, referring to the Jesuit concept of always seeking more opportunities to help others.

“If my small gesture helps one student do one simple thing much easier, and with less pain,” she said, “I feel very blessed.”

Donate to the Fordham Ukraine Crisis Student Support Fund.

To apply for assistance from this fund, please contact Brian Ghanoo, assistant vice president, Office of Student Financial Services, at 718-817-3811 or [email protected].

]]>“I don’t want to leave Kyiv. I was born here. I love Kyiv. Kyiv is the most beautiful city in the world,” said Vitaly Chernoivanenko, Ph.D., a Ukrainian scholar who spoke at a Fordham virtual panel on March 17. “I’m not afraid of Putin and his military forces.”

The panel is part of a new Fordham initiative designed to help Ukrainians during the Russia-Ukraine war. Fordham’s Center for Jewish Studies is co-hosting a virtual lecture series that discusses how the current crisis is affecting academia and co-sponsoring a fellowship program for Ukrainian scholars. The center is collaborating with three organizations: the American Academy for Jewish Research, the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in Germany, and the Lviv Center for Urban History in Ukraine.

“With people in war zones and in exile from their homes and in need of basic supplies, it may not seem urgent to give attention to scholarship. Nevertheless, society also depends on those who create and preserve knowledge through their scholarship, work, and institutions devoted to research and culture,” said Magda Teter, Ph.D., Fordham’s Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies and a professor of history who is moderating the lecture series.

The first lecture featured two Ukrainian scholars: Chernoivanenko, a senior research fellow at the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine and president of the Ukrainian Association for Jewish Studies, and Sofia Dyak, Ph.D., a historian and director of the Lviv Center for Urban History. The panel was moderated by Teter and Iryna Klymenko, Ph.D., a European history scholar from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

‘We Don’t Think About the Office or Our Laptops. We Think About People’

Chernoivanenko reflected on how the past three weeks have affected his professional and personal life. As a scholar who specializes in Jewish studies, preserving the work of his predecessors and colleagues is important, he said, especially in Ukraine, where his scholarship was once banned under Soviet rule.

“It’s a miracle that for these 30 years since our independence was proclaimed in 1991, we have a very prospective field … All these scholars sincerely want to research Jewish heritage of Ukraine and Eastern Europe,” said Chernoivanenko, who established the first Ukrainian peer-reviewed journal in Jewish studies and the first master’s degree program in Jewish studies in Ukraine. “It’s very important to preserve this heritage, especially now during the war.”

Chernoivanenko said many of his colleagues are still in Ukraine, where they are doing what they can to help with the war effort.

“We don’t think about the office or our laptops. We think about people, our colleagues,” said Chernoivanenko, speaking from Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine.

Chernoivanenko said he has been assisting local defense forces and strangers in the streets, including the homeless population. He added that he is thankful for his colleagues across the world who invited him to flee Ukraine by taking scholarship positions in their schools, but he said he wanted to stay home and help. His father and mother, who are 74 and 73, respectively, aren’t fleeing either, he said.

“My parents are very brave,” he said. “They said no, never. We believe in our military forces.”

Protecting Heritage and New Priorities

Scholars in Ukraine and those who have fled the country both need support, said Teter and Klymenko. There are opportunities that can help scholars who live anywhere, like the new fellowship co-sponsored by Fordham’s Center for Jewish Studies and the American Academy for Jewish Research, said Teter, which consists of a $5,000 stipend, remote access to library resources, and networking with faculty members from both institutions. Klymenko added that her own university’s history department has been providing financial aid and refuge for displaced Ukrainian scholars in Germany. Most of the refugees are women with children and elderly parents, she said.

“These are people, mainly scholars, who are basically trying to save their children from being further traumatized,” said Klymenko, who is affiliated with the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in Germany.

The war has also changed people’s views on the preservation of heritage, said Dyak, director of a research institution in Lviv, Ukraine. Her colleagues have been wondering whether or not their artifacts should be wrapped, hidden, or moved. They have also accommodated their facilities to the realities of wartime, she said.

“We turned our conference room and cafe into shelters … We are discussing [playing]cartoons and classic films for kids, but not home movies because that would be very painful. The shelter is for people who lost their homes or probably can’t go back to their homes,” Dyak said.

A Silver Lining and Hope

There is a silver lining within the chaos of the current crisis, said Teter.

“It is terrible that a war had to happen, but it puts your voices out there and makes the world discover the amazing scholarship that is being produced in Ukraine and your centers and institutions,” Teter said, directly addressing the panelists.

It is unclear when Ukrainian scholars will continue their partnerships with Russian scholars and institutions, said Dyak. She added that the path to collaboration will require much introspection on Russia’s part.

“Cultural arrogance can lead to violence,” Dyak said. “I am hopeful that in the future, from our shared experiences, we will be able to revisit, in a new way, conversations that are painful and hard … Right now we probably are not able to pick up these conversations, but I do hope that these shared experiences will create a space of trust.”

The second lecture will be held this Thursday, March 24, at 10 a.m. EST. Watch a full recording of the first lecture below:

]]>