In October of 2012, Fordham marked the 100th anniversary of the lectures with a two-day conference featuring dozens of Jungian scholars.

“In Fordham’s history it’s a legendary event,” said Mark Mattson, PhD, associate professor of psychology.

Now Mattson, an organizer of the 2012 event, and Frederick Wertz, PhD, professor of psychology and associate chair for undergraduate studies at Lincoln Center, have edited and published the papers presented at the conference. Jung in the Academy and Beyond: The Fordham Lectures 100 Years Later (Spring Journal Books, 2015) also includes an essay by Wertz for the book.

Mattson said that psychoanalysis was still in its infancy at the time of Jung’s lectures. The event was touted as a chance for practicing physicians to continue their education—in this case, a newly developing science from Europe.

Mattson said that psychoanalysis was still in its infancy at the time of Jung’s lectures. The event was touted as a chance for practicing physicians to continue their education—in this case, a newly developing science from Europe.

“Doctors were always bemoaning that psychiatry should be much more scientific,” said Mattson. “Since the lectures were held in New York they were able to bring together an international cast to discuss that.”

In discussing his essay, Wertz said that while many believe that the Fordham Lectures caused the infamous rupture between Jung and Freud, Wertz said that close reading of letters between the two revealed that the lectures did not play a role. Jung was in continuous contact with Freud before and after the lectures, to let him know that he would be contradicting his theory.

“Freud was nervous,” said Wertz. “It was significant and bold for Jung and he did exactly what he said he would do—he criticized Freudian theory and presented the kernel of all his ideas.” Six months later, the two had their famous break.

Wertz’s essay serves as the book’s first chapter. In thoroughly exploring the issues, Wertz concludes Jung affirmed and used Freud’s methods unaltered, and diverged only from his theories. The break was personal, not professional.

“When you read the lectures you see that Jung credits Freud and that he is informed, illuminated, guided, and trained by Freud in his methods of investigation,” he said. Freud expected that scientists would modify his work, said Wertz.

Nevertheless, in the lectures Jung diverged from Freud’s methods, but it was not cause enough for a break.

“Freud was a scientist not a dogmatist,” said Wertz.

When Jung returned to Europe he sent a copy of the lectures to Freud, who responded by saying that Fordham lectures were “excellent.”

“These were disagreements among scientists, the break took place for personal reasons, not theoretical difference. ”

]]>

Photo by Michael Dames

Renowned psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Jung delivered a series of lectures that outlined the future of his work in psychoanalysis—including a decisive break from the theories of his friend and colleague, Sigmund Freud.

A century later, Jung remains a luminary of psychoanalysis, and his theories are applied beyond psychology to disciplines ranging from theology to ecology.

“[The lectures] mark an important event—the break between Freud and Jung,” said Mark Mattson, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology and associate dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center. “Now we’re reexamining it and seeing how that plays out today.”

On Oct. 26 and 27, Fordham, in conjunction with the Jungian Psychoanalytic Association (JPA), marked the 100th anniversary of the 1912 lectures with a two-day conference. Bringing together dozens of Jungian scholars and clinicians on the site of the original lectures, the conference examined the importance of Jung’s time at Rose Hill and illuminated the ways Jung’s thought has influenced both modern culture and academia throughout the century.

“This is something we’ve been talking about as an important event in Fordham history for 100 years,” Mattson said.

The lectures—which were recently republished in Jung Contra Freud (Princeton University Press, 2012)—were part of a month-long international course hosted by what was then Fordham’s School of Medicine, on the latest research on nervous diseases.

It was during these lectures that Jung publicly distanced himself from some of Freud’s principal tenets of psychoanalysis, much to Freud’s dismay.

“In the early 1900s, Freud was trying to broaden the appeal of psychoanalysis beyond just Viennese physicians, and here was [Jung], who had a good reputation in other areas,” Mattson said. “Freud thought of him as an heir apparent, who could internationalize psychoanalysis.”

Their divergence in thinking led to a dramatic change in their relationship. Margaret Klenck, president of the JPA, opened the conference by reading a letter that Jung sent to Freud following the Fordham lectures, explaining his new claims and imploring Freud to not view them as a personal slight.

Leading up to the nine Fordham lectures, Jung had struggled to reconcile himself to Freud’s belief that repressed sexual urges cause neurotic behavior. He instead thought the connection between the two was metaphorical rather than literal. Ultimately, he decided he could no longer endorse Freud’s views in this matter. Jung explains in the letter that his own version of sexuality and neurosis won over participants, many of whom had found Freud’s theories outlandish.

“‘With me, it is not a question of caprice, but a fighting for what I hold to be true,” Klenk read from Jung’s letter. “On the other hand, I hope this letter will make plain that I feel no need at all to break off personal relations with you. I do not identify you with a point of doctrine, and I’ve always tried to play fair with you and shall continue to do so,’” Jung wrote.

Ultimately, Klenck said, the two men parted ways.

The October conference at Fordham covered an array of topics, including how Jung’s psychoanalytic theories developed following the 1912 lectures and how his thinking is relevant today in areas such as climate change and the Jesuit tradition of the Spiritual Exercises.

Joseph Cambray, Ph.D., president of the International Association for Analytical Psychology and faculty member in Harvard Medical School’s Department of Psychiatry, gave the opening lecture for more than 100 attendees. Cambray explained how science and German romanticism intersected in the 19th and 20th centuries, and how both of these traditions informed Jung’s approach to science.

This romantic approach to science—which stresses the importance of emotions and imagination—could benefit today’s scientific theories, Cambray said.

“The return of subjectivity, affect, and imagination to scientific discourse can naturally be seen as an affirmative return to the scientific tradition [of romanticism],” he said.

Renowned psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Jung delivered a series of lectures that set the stage for his future work—including a decisive break from the theories of his friend and colleague, Sigmund Freud.

On Oct. 26, Fordham will mark the 100th anniversary of this milestone in psychoanalysis with a two-day conference at the site of the original lectures.

To learn more about the conference, visit the page on Inside Fordham.

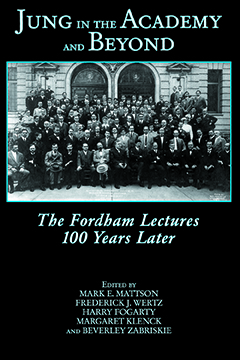

The original participants of the “International Extension Course in Medical and Nervous Diseases,”

Sept. 9 through 28, 1912, at Fordham University.

Photo courtesy of Fordham Archives

— Joanna Klimaski

Courtesy of Fordham Archives

In September of 1912, Fordham was the site of a watershed moment in the history of psychoanalysis.

Renowned psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Jung delivered a series of lectures that outlined the future of his work—including a decisive break from the theories of his friend and colleague, Sigmund Freud.

Jung in the Academy and Beyond will kick off with a free public lecture on Friday, Oct. 26 at 7 p.m., in Keating First Auditorium, by Joseph Cambray, Ph.D., president of the International Association for Analytic Psychology and a faculty member at Harvard Medical School, titled “Jung, Science, and German Romanticism: A Contemporary Perspective.”

The conference will continue on Saturday, Oct. 27, beginning at 8:30 a.m. in Tognino Hall, Duane Library, featuring keynote speakers: Eugene Taylor, Ph.D., professor of psychology at Saybrook University and senior psychologist with the psychiatry service at Massachusetts General Hospital; Ann B. Ulanov, Ph.D., the Christiane Brooks Johnson professor of psychiatry and religion at Union Theological Seminary; and Martin A. Schulman, Ph.D., former editor of The Psychoanalytic Review, which published Jung’s original lectures in its inaugural edition.

For registration and schedule information, visit [email protected].