Since the 1970s, Fordham students have been studying and contributing to the spirit of innovation and community renewal that has come to define what it means to be a Bronxite.

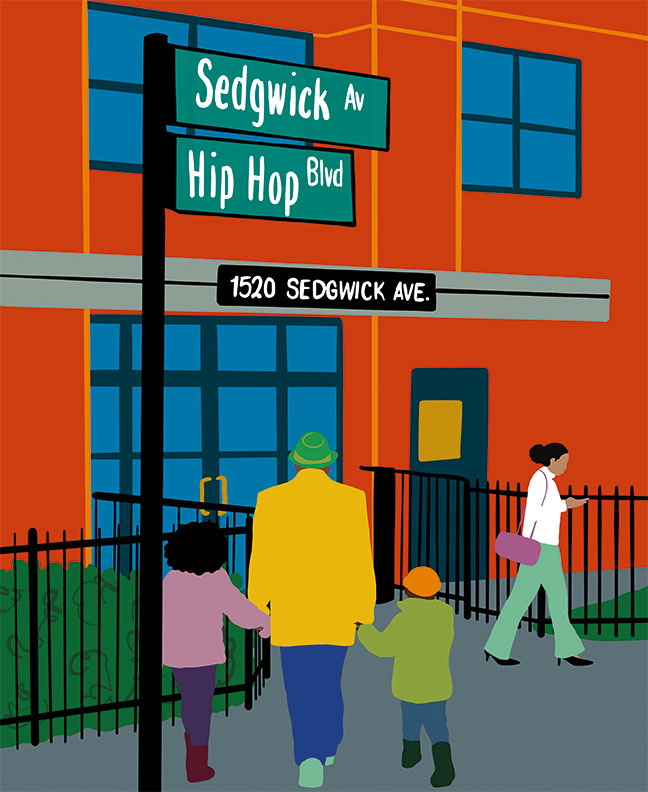

Fifty years ago, a new art form burst forth on the streets of the Bronx, born from rich musical traditions and a spirit of innovation in neighborhoods of color ravaged by deindustrialization and written off by most of the country. In the ensuing decades, the Fordham community has not only studied and celebrated hip-hop as a revolutionary cultural force but also helped preserve its Bronx legacy—through efforts to recognize the apartment building at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue as the genre’s birthplace, and through oral-history interviews with some of hip-hop’s seminal figures.

“I think the lesson is, let’s explore, interrogate, and embrace the cultural creativity of our surrounding areas because it’s unparalleled,” said Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of African and African American studies and founding director of Fordham’s Bronx African American History Project.

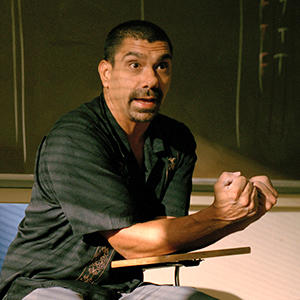

Naison teaches a popular class, From Rock and Roll to Hip-Hop, that draws on artists like Cardi B, Nas, and Run-DMC to understand the music and its part in U.S. history—and to explore issues he’s spent his career teaching. “I’m not a hip-hop scholar,” he said. “Rather, I’m someone who works to have community voices heard.”

And just as the music has evolved over the past 50 years, so have efforts to revitalize the borough and tell the stories of its residents.

Challenging ‘Deeply Entrenched Stereotypes’

Amplifying community voices is at the heart of the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). Fordham launched the project in 2002, at the request of the Bronx County Historical Society, to document and preserve the history of Black people in New York City’s northernmost borough. Naison and his team of Fordham students, faculty, and community historians have spoken with hip-hop pioneers like Pete DJ Jones and Kurtis Blow, but the project is much broader: The archive contains verbatim transcripts of interviews with educators, politicians, social workers, businesspeople, clergy members, athletes, and leaders of community-based organizations who have lived and worked in the Bronx since the 1930s. The archive, which also includes scholarly essays about the Bronx, was digitized in 2015, making the interviews fully accessible to the public.

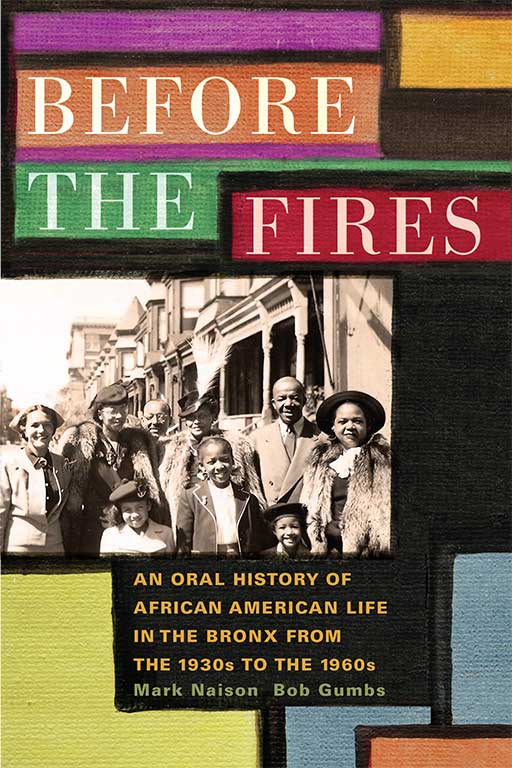

“Starting by interviewing a small number of people I already knew,” Naison wrote in Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life in the Bronx from the 1930s to the 1960s (Fordham University Press, 2016), “I stumbled upon a large, passionate, and knowledgeable group of people who had been waiting for years to tell stories of communities long forgotten, communities whose very history challenged deeply entrenched stereotypes about Black and Latino settlement of the Bronx.”

For Naison, the project highlights how the borough, defying the odds, rebuilt neighborhoods following the arson of the 1970s and the crack epidemic of the 1980s. The neighborhoods, with lower crime rates, saw community life flourish again, and in recent decades, the Bronx became a location of choice for new immigrants to New York. BAAHP research includes interviews with Bronxites from Ghana, Nigeria, Mali, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Burkina Faso, among other nations. It gives voice to growing, diverse immigrant communities that have enlivened Bronx neighborhoods where Jewish, Irish, Italian, Puerto Rican, and Dominican people lived before them. “The Bronx is this site where people mix their cultures and they create something new,” Naison said. “It makes this a lot of fun to study.”

For Naison, the project highlights how the borough, defying the odds, rebuilt neighborhoods following the arson of the 1970s and the crack epidemic of the 1980s. The neighborhoods, with lower crime rates, saw community life flourish again, and in recent decades, the Bronx became a location of choice for new immigrants to New York. BAAHP research includes interviews with Bronxites from Ghana, Nigeria, Mali, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Burkina Faso, among other nations. It gives voice to growing, diverse immigrant communities that have enlivened Bronx neighborhoods where Jewish, Irish, Italian, Puerto Rican, and Dominican people lived before them. “The Bronx is this site where people mix their cultures and they create something new,” Naison said. “It makes this a lot of fun to study.”

Shaping Global Perceptions

Brian Purnell, Ph.D., FCRH ’00, helped facilitate at least 50 BAAHP interviews from 2004 to 2010, when he was the project’s research director. He said the archive is useful for anyone studying how cities have changed over the decades.

“I hope people use it to think differently about the Bronx, to include the Bronx more deeply and broadly in urban studies in the United States,” said Purnell, now an associate professor of Africana studies and history at Bowdoin College, where he uses the Fordham archive in his own research and in the classroom with his students. “I hope that it also expands how we think about Black people in New York City and in American cities in general from the mid-20th century onward.”

Since 2015, when the BAAHP archives were made available online, the digital recordings have been accessed by thousands of scholars around the world, from Nairobi to Singapore, Paris to Berlin. Peter Schultz Jørgensen, an urbanist and author in Denmark, has been using information from the digital archive to complete a book titled Our Bronx!

“Portraying and documenting everyday life in the Bronx, as it once was, is essential in protecting the people of the Bronx from misrepresentation, while at the same time providing valuable knowledge that can help shape their future,” he said. “Just as BAAHP gathers the web of memory, my book is about the struggles that people and community organizations have waged and are waging in the Bronx. And more important, and encouraging, it talks about how they are now scaling up via the Bronxwide Coalition and their Bronxwide plan for more economic and democratic control of the borough.”

Championing Bronx Renewal

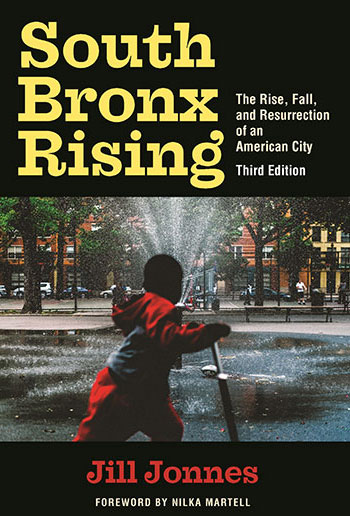

The movement Jørgensen describes is one in which members of the Fordham community have long played key roles, according to historian and journalist Jill Jonnes, author of South Bronx Rising: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of an American City. In the mid-1980s, when she published the first edition of the book, Bronxites were just beginning to reverse the toxic effects of long-term disinvestment and arson that had ravaged the borough.

“Today, we far better understand the interplay of blatantly racist government policies and private business decisions … that played a decisive role in almost destroying these neighborhoods,” Jonnes wrote in a preface to the third edition of South Bronx Rising, published last year by Fordham University Press. “Even as fires relentlessly spread across the borough—as landlords extracted what they could from their properties regardless of the human cost—local activists and the social justice Catholics were mobilizing to challenge and upend a system that rewarded destruction rather than investment.”

“Today, we far better understand the interplay of blatantly racist government policies and private business decisions … that played a decisive role in almost destroying these neighborhoods,” Jonnes wrote in a preface to the third edition of South Bronx Rising, published last year by Fordham University Press. “Even as fires relentlessly spread across the borough—as landlords extracted what they could from their properties regardless of the human cost—local activists and the social justice Catholics were mobilizing to challenge and upend a system that rewarded destruction rather than investment.”

One of those Catholics was Paul Brant, S.J., a Jesuit scholastic (and later priest) who arrived at Fordham’s Rose Hill campus in the late 1960s to teach and to pursue graduate studies in philosophy. At the time, faith in the viability of cities was at a low point. Deindustrialization, suburbanization, and two decades of studied underinvestment had taken their predictable toll. The Bronx was experiencing the worst of it, and the people who lived in its neighborhoods were demonized as the cause of the problems.

Brant, who died in May 2023 at the age of 82, wanted to understand what could be done. He earned a spot in New York City’s prestigious Urban Fellows program, meant to harness ideas for a city in crisis. Gregarious and forceful, yet able to work diplomatically, he had the backing of Fordham’s president at the time, James Finlay, S.J., to serve as the University’s liaison to the Bronx. With other young Jesuits, he lived in an apartment south of campus, on 187th Street and Marion Avenue, gaining firsthand insight into the scope of neglect and abandonment afflicting the borough.

“Paul felt, well, look, there’s a lot of people still in these neighborhoods. It’s not inevitable that everything gets worse,” said Roger Hayes, GSAS ’95, one of Brant’s former Jesuit seminary classmates. “What are we going to do?”

Long conversations with Hayes and Jim Mitchell, another seminary friend, convinced Brant that solutions to the Bronx’s problems would come by directing the power of the people themselves. In 1972, they formed a neighborhood association in nearby Morris Heights. They used relationships within the parish to confront negligent landlords. Seeing nascent successes there, they moved to launch a larger group.

In 1974, Brant convinced pastors from 10 Catholic parishes to sponsor an organization to fight for the community, and the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition (NWBCC) was born. The group expanded to include Protestant and Jewish clergy—membership was always nonsectarian—and went on to train leaders in hundreds of tenant associations and neighborhood groups, including the University Neighborhood Housing Program, which Fordham helped to establish in the early 1980s to create, preserve, and improve affordable housing in the Bronx, and which has been led for many years by Fordham graduate Jim Buckley, FCRH ’76.

All of these groups were knit together across racial lines and around share interests during the worst years of abandonment and destruction. When they learned that rotten apartments had roots beyond individual slumlords, they picketed banks for redlining, the practice of withholding loans to people in neighborhoods considered a poor economic risk. Before long, Bronx homemakers and blue-collar workers were boarding buses to City Hall, demanding meetings with commissioners and testifying at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

With similar people-power organizations nationwide, they won changes in the nation’s banking laws through the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, drove reinvestment to cities, and sprouted a new ecosystem of nonprofit affordable housing.

Preserving Hip-Hop’s Bronx Birthplace

It’s the stuff of legend now: On August 11, 1973, Cindy Campbell threw a “Back to School Jam” in a recreation room at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, a 100-plus-unit apartment building just blocks from the Cross Bronx Expressway in the Morris Heights neighborhood of the Bronx. Her brother, Kool Herc, DJ’d the party, which came to be considered the origin of hip-hop music.

Fast forward to 2008, when 1520 Sedgwick was laden with debt acquired by Wall Street investors who were failing to maintain the building. Organizers from the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board, a group focused on preserving affordable housing, hoped that documenting 1520’s history would help save it. They asked Fordham professor Mark Naison, Ph.D., to help. His research—which led to a lecture on C-SPAN and was highlighted in an August 2008 appearance on the PBS show History Detectives—helped convince the city government to intervene, eventually preserving the building as a decent and affordable place to live. In 2021, its standing became official: The U.S. Congress adopted a resolution acknowledging 1520 Sedgwick as the birthplace of hip-hop.

Learning About Bronx Renewal

Each year, Fordham’s Center for Community Engaged Learning shares this view of Bronx (and Fordham) history with incoming students, particularly those who participate in its Urban Plunge program in late August. The pre-orientation program gives new students the chance to explore the city’s neighborhoods and join local efforts to foster community development.

“For 30 years, the Plunge experience has offered our students their first introduction to institutions like Part of the Solution and the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, organizations founded by Fordham community members in collaboration with local residents that have built community, advocated for justice, and provided services and resources for the whole person,” said Julie Gafney, Ph.D., Fordham’s assistant vice president for strategic mission initiatives and executive director of the Center for Community Engaged Learning.

Students learn directly from local residents and policy experts about how they can shape policy decisions and build a better future for Fordham and its neighbors. “We really want to introduce first-year students, along with their upper-class mentors, to what’s driving community work in the Bronx right now,” Gafney said. “It’s an ideal ground for fostering a four-year commitment to community solution-building here in the Bronx.”

Reimagining the Cross Bronx

On August 25, nearly 250 first-year Fordham students fanned out across the Bronx as part of Urban Plunge. They served lunch to those in need at POTS—Part of the Solution, where Fordham graduate Jack Marth, FCRH ’86, is the director of programs; they helped refurbish Poe Park and the community-maintained Drew Gardens, adjacent to the Bronx River; and they visited the NWBCCC, now led by Fordham graduate Sandra Lobo, FCRH ’97, GSS ’04.

Students also learned about the Cross Bronx Expressway, a major highway built in the mid-20th century that has been blamed not only for separating Bronx communities but also for worsening air and noise pollution in the borough, contributing to residents’ high rates of asthma and other respiratory diseases.

Before visiting parts of the expressway, students heard from Nilka Martell, founding director of Loving the Bronx, a nonprofit that has been leading community efforts to cap the Cross Bronx and develop public green spaces above and around it. A few years ago, Martell connected with Fordham graduate Alex Levine, FCRH ’14, who was pursuing the same goal.

Before visiting parts of the expressway, students heard from Nilka Martell, founding director of Loving the Bronx, a nonprofit that has been leading community efforts to cap the Cross Bronx and develop public green spaces above and around it. A few years ago, Martell connected with Fordham graduate Alex Levine, FCRH ’14, who was pursuing the same goal.

At Fordham, Levine majored in economics and Chinese studies and interned at the Department of City Planning in the Bronx. By 2020, he was a third-year medical student at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, where he co-founded the Bronx One Policy Group, a student advocacy organization focused on capping an approximately 2.5-mile section of the Cross Bronx that runs below street level. The idea is to cover the road with parks and install vents to remove toxic fumes caused by vehicular traffic. They said the cost of the project, estimated to be about $1 billion, would be offset by higher property values and lower health care costs.

“When you think of preventive medicine, it impacts everyone’s life,” Levine told the Bronx Times in 2021. “If we can get a small portion of this capped, then it might be a catalyst to happen on the rest of the highway. This is a project that can save money and lives.”

Martell said Levine’s group connected her with Dr. Peter Muennig, a professor at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health who had published a study on the benefits of capping the Cross Bronx.

“We created this perfect trifecta,” she said. They brought their idea to Rep. Ritchie Torres, and in December 2022, the city received a $2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation to study how to reimagine the Cross Bronx. Fordham’s Center for Community Engaged Learning later received a $25,000 grant from the New York City Department of Transportation as one of only 10 community partners selected to help the department gather input from residents who live near the expressway.

The feasibility-study funding is just a first step, Martell told students during an Urban Plunge panel discussion that featured a representative of the city planning department’s Bronx office and an asthma program manager from the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. “This isn’t easy,” Martell said. “If this was easy and there was a point-by-point playbook on how to get it done, all these projects would happen.”

But recent Bronx history gives her ample reason to press on. “You know, 40 years ago, we had the restoration of the Bronx River. Fifty years ago, we had the creation of hip-hop.” When there was little support and “no other outlet,” she said, “Bronxites came together to create an outlet.”

“For me, this is what it’s like to be a Bronxite; this is what it’s like to be in the Bronx—to have this kind of energy and these organizing skills to get things done.”

—Eileen Markey, FCRH ’98, teaches journalism at Lehman College and is working on a book about the people’s movement that helped rebuild the Bronx in the 1970s and ’80s. Taylor Ha is a senior writer and videographer in the president’s office and the marketing and communications division at Fordham.

]]>

When 1520 Sedgwick Avenue—the Bronx building considered by many to be the place where hip-hop began—had fallen into disrepair, Fordham professor Mark Naison, Ph.D., contributed his research to community organizers who were trying to save it. He also led other Fordham efforts to preserve hip-hop’s past, including the University’s Bronx African American History Project’s (BAAHP) interviews with artists from the early days of the genre, which created an important collection of oral histories from DJs and MCs. Naison also teaches a popular class called From Rock and Roll to Hip-Hop that spans past to present, drawing on artists like Cardi B, Nas, Run DMC, and onetime Fordham “rapper-in-residence” Akua Naru to help students understand the art form and its part in U.S. history.

“I think the lesson is, let’s explore, interrogate, and embrace the cultural creativity of our surrounding areas because it’s unparalleled,” said Mark Naison, Ph.D., director of the BAAHP and professor of African American Studies and History.

The Party That Started It All

It’s the stuff of legend now: On August 11, 1973, teenager Cindy Campbell hosted a back-to-school party in the community room of her building at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, just blocks from the Cross Bronx Expressway. She charged admission and had her brother Clive, aka DJ Kool Herc—they called him Hercules because he was so big—spin some records. Herc had been practicing on his father’s sound system, jumping just to the hottest percussive grooves—the bits where dancers really got down—and stretching those out by manipulating two copies of the same record. He had two turn tables and a microphone, and played a mix of funk and disco that he blended with the talking-over style he’d grown up hearing in Jamaican dancehall music. While many have pointed out that the art form was developing in other places as well, that party is commonly celebrated as the birth of hip-hop.

Saving 1520 Sedgwick

Fast forward 40 years to the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008. In a perverse inversion of the redlining that had devastated the Bronx at the time of hip-hop’s birth, 1520 was now laden with debt acquired by Wall Street investors who were failing to maintain the building. Organizers from the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board, a group focused on preserving affordable housing, hoped documenting 1520’s history would help save it. They asked Naison to put his scholarly acumen into determining 1520’s significance. Naison’s research—which later led to a lecture on C-Span and an appearance on PBS’ History Detectives —was among the efforts that helped convince city government to intervene, eventually preserving the building where hip-hop was born as a decent and affordable place to live. And in 2021 the U.S. Congress adopted a resolution acknowledging 1520 Sedgwick as the birthplace of hip-hop.

In Their Own Words

Brian Purnell, FCRH ’00, former research director of the BAAHP and current associate professor of African American Studies at Bowdoin College, said hip-hop culture “exemplifies hallmarks of the long history of Black culture in the U.S.”

“Hip-hop turned the supposed blight of the context its creators lived in into something stunning and fantastic and beautiful—and this is tried and true to Black culture over the centuries,” he said.

In 2003, Fordham formed the BAAHP, at the request of the Bronx County Historical Society, to document the history of Black people in the Bronx. Naison said soon DJs and MCs were calling saying, “Aren’t you going to record our story?”

Over the next several years BAAHP built an archive of interviews with some of the first hip-hop practitioners like Pete DJ Jones and Kurtis Blow, as well as Benjy Melendez —who in 1971 brokered a gang truce allowing the movement between neighborhoods that pollinated the music. The digital recordings have been accessed by scholars the world over, from Nairobi to Singapore, Paris, and Berlin.

WFUV in the House

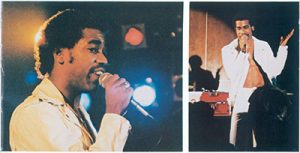

One of those early hip-hop DJs, Eddie Cheeba, spun both in downtown clubs and uptown parties. In the summer of 1978 he worked at Fordham’s radio station WFUV. He rapped about it at a legendary 1979 party with Melle Mel, Grandmaster Flash, and DJ Hollywood: “Cheeba’s gonna be the winner. I’m mean, I’m bad, I’m cool and smooth, so I know you’ll do it with me. I guess that’s why I ran my game on WFUV. (22-minute mark)”

‘It Was Black People Being Free’

Michael Partis, FCRH ’08, who grew up in the Bronx and has contributed to the BAAHP, said preserving that joy and experimentation palpable in the first years of hip-hop is crucial.

“I think it’s important that the history of hip-hop is documented, because it really shows Black freedom. In this country people of African descent are often tied down by segregation and racism, by respectability that says you can’t be a certain way,” he said. “And hip-hop in its earliest form kind of broke through all that stuff. It was Black people being free.”

While Partis was at Fordham, a student-led Hip-Hop Coalition focused on the politically conscious roots of hip-hop. They brought acts to campus that weren’t mainstream or corporate. “These were street guys who were talking about socioeconomic inequality, and how these working poor communities, Black and Brown working communities, responded to that,” he said. “I thought it was excellent political education for the Fordham kids,” he said.

Today, Naison is helping to continue that education at Fordham.

“I’m not a hip-hop scholar, rather I’m someone who works to have community voices heard,” he said.

The Power—and Reach—of the Music

“When students in my class study hip-hop, there are two things that make the most powerful impression on them: First, the power of the best hip-hop artists, like Tupac Shakur, Lauryn Hill, and Wu-Tang Clan, to tell stories that can touch your heart strings as well as make you think. And second, the truly global impact of hip-hop, which includes dance and visual arts as well as music and is now deeply entrenched in Europe, Africa, and Asia, as well as the Western Hemisphere,” he said.

“Hip-hop was a multicultural arts movement of the most isolated, marginalized, disenfranchised people in society and they created a movement that swept the world.”

–By Eileen Markey, FCRH ’98

]]>“We had downloads from Ukraine and the Russian Federation on the same day—two countries at war with one another,” said Mark Naison, Ph.D., co-founder of BAAHP and professor of history and African & African American studies at Fordham. “It’s so exciting that people all over the world are interested in our interviews and essays.”

Downloads From Nearly Every Continent

BAAHP was founded more than two decades ago in collaboration with the Bronx County Historical Society in order to preserve the history of the Bronx and its people. The bulk of the archive contains verbatim transcripts of interviews with political leaders, educators, musicians, social workers, businesspeople, clergy, athletes, and leaders of community-based organizations who have lived and worked in the Bronx since the 1930s, in addition to scholarly essays about the Bronx. For many years, these articles lived on audio tapes and paper. In 2015, they were uploaded to a digital archive that made their stories fully accessible to the public.

Since then, thousands of scholars, students, and strangers have accessed the digital archive from around the world. People in Europe, Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Caribbean have downloaded resources from the archive, according to data from Fordham Libraries. Online visitors in Singapore and Paris even downloaded the entire archive twice, said Naison.

Among the scholars is Peter Schultz Jørgensen, an urbanist and author in Denmark who is using information from the digital archive to complete his upcoming book “Our Bronx!”

“Portraying and documenting everyday life in the Bronx, as it once was, is essential in protecting the people of the Bronx from misrepresentation, while at the same time, providing valuable knowledge that can help shape their future,” Jørgensen said. “Just as BAAHP gathers the web of memory, my book is about the struggles that people and community organizations have waged and are waging in the Bronx. And more important, and encouraging, it talks about how they are now scaling up via the Bronx Wide Coalition and their Bronx Wide Plan for more economic and democratic control of the borough.”

The archive is also helpful for those who aren’t familiar with the Bronx, said Mattieu Langlois, a history Ph.D. student in Fordham’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

“I’m from Canada, so I didn’t know much about the Bronx,” said Langlois, who served as a BAAHP graduate assistant, ensuring interviews were transcribed correctly and uploading them to the archive. “It’s a good source of information for many people.”

A Treasure Trove for Scholars

It’s unclear what thousands of other visitors are searching for in the archives, said Naison, but he suspects that some are scholars who are researching the history of hip-hop, a genre born in the Bronx that has influenced scores of artists, including Bronx-born rappers like Cardi B and Lil Tjay. Other scholars might be studying immigration—and the Bronx, a city heavily shaped by immigration, is a great model, said Naison.

“The Bronx has a global reputation for music, but also for immigration and the mixing of cultures,” Naison said. “And our archive brings that to life.”

‘I Hope People Use It To Think Differently About the Bronx’

Brian Purnell, Ph.D., FCRH ’00, a former BAAHP research director from 2004 to 2010 who helped to facilitate at least 50 interviews in the archive, said the archive is also useful for urban studies scholars who are studying how cities have changed over the decades.

“I hope people use it to think differently about the Bronx, to include the Bronx more deeply and broadly in urban studies in the United States,” said Purnell, now an associate professor of Africana studies and history at Bowdoin College, who uses the archive in his own research and in the classroom with his students. “I hope that it also expands how we think about Black people in New York City and in American cities in general from the mid-20th century onward.”

Naison said his team plans to upload more interviews to the archive—and that their work won’t stop there.

“It’s ongoing. It’s exciting,” said Naison. “And to know now that people all over the world are interested in this, it makes it even more motivating to keep it going.”

]]>“We’re working on having our students understand that what goes on outside is community. It’s love. It’s history,” said Lisa Preti, an assistant director in student financial services at Fordham and the mural project manager. “We’re having people actually immerse themselves in the community, as opposed to just learning about it in the classroom.”

The initiative was spearheaded by Fordham Bronx Advocates, a grassroots group of 10 to 15 Fordham community members and Bronx residents whose goal is to create a stronger partnership between Fordham and its neighbors. The mural is the first major project for the group, which was founded by Preti and her colleague Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of history and African and African American studies, this past fall semester. The large scale artwork is being painted on a side wall of the John E. Grimm III Clubhouse, a center that offers academic and recreational activities for young people in the community, said Preti.

“The first building I saw right across the street from Fordham was the clubhouse on 189th Street and Lorillard Place. I went in and asked them if they were interested in creating a mural on site, and they said, ‘Yes, absolutely—we’ve been looking to do something like that for a long time,’” said Preti. “It’s really just taken off from there.”

The mural was designed by Lovie Pignata, a Bronx artist and community activist, and funded by several Fordham groups and departments including the Bronx African American History Project, the Office of the Chief Diversity Officer, the Fordham College Dean’s Office, and the Center for Community Engaged Learning. Project organizers also received free paint, rollers, and supplies from the nearby New Palace Paint & Home Center on 180th Street, said Preti.

“It was amazing to see the community so quickly say, yes, we’ll help,” said Preti, a Bronx native whose parents still reside in the borough. “It started as a small grassroots movement, and we got lucky along the way.”

In mid-April, the artist behind the mural, Pignata, met with Fordham student volunteers and the clubhouse’s teenagers and staff to transform a plain brick wall into a garden mural bursting with colorful fruits, vegetables, and flowers. The mural includes several symbols, including root vegetables, which represent hidden potential, said Pignata.

After the mural is completed in May, the clubhouse will plant an actual community garden in front of the mural to help combat local food insecurity. Three planter boxes have been donated by the Northeast Bronx Community Farmers Market Project, which will also provide seedlings, said Pignata.

“The theme of the mural is ‘growing together,’” Pignata said. “I like to make what I call community art, which is more hands-on and has more interaction with the people who will live near it [than public art]. I hope everybody involved in the mural is proud of it and feels like they’re a part of it.”

Isabella Iazzetta, a junior at Fordham College at Rose Hill who has participated in two painting sessions, said her volunteer experience has introduced her to more members of the Bronx community, including elementary school students who walk by and marvel at the mural. This summer, Iazzetta will be able to walk past the finished mural every day.

“My roommates and I are actually moving off campus on that same block,” said Iazzetta, who studies humanitarian studies and theology religious studies at Fordham. “It’ll be so cool to look at and know that I had a tiny role in helping this all come to life.”

On July 23, Bronx high schoolers, mentored by four Fordham undergraduates, presented research that challenged negative stereotypes of the borough. They showed their findings to the community via Zoom as the culmination of the annual Bronx History Makers program, an immersive college-prep experience that began in 2005.

Supported by a grant of $50,000 from the Teagle Foundation, Fordham’s Center for Community Engaged Learning worked in partnership with BronxWorks, a nonprofit community organization, to recruit the high school scholars, the Fordham undergraduate mentors, and faculty for the project, as well as a cross-section of experts on the borough.

This year’s faculty supervisors were Clarence Edward Ball III, lecturer of communications and media management at the Gabelli School of Business, and Gregory Jost, adjunct professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology. The program normally runs for six weeks on campus, but because of the pandemic it was reduced to two weeks of preparation for the college mentors and two weeks of research with high school scholars.

This summer, the undergraduate mentors met for two weeks to learn the material that they would be researching with the high school scholars. In the process, they got to know each other well enough to form a tightly organized team. As with the six-week program, the mentors taught the scholars the history of the topics and were charged with supporting the scholars as they navigated research and execute a typical college assignment. The four teams examined issues facing the Bronx, said Ball, including redlining, racial inequities, community policing, and gentrification. The intent was not only to expose the scholars to college coursework, but also to the culture of higher education.

Normally, there would be field trips and the students would stay in student housing on campus with the mentors. But instead, due to the pandemic, the mentors and scholars worked virtually via Zoom. Making a real connection was made possible largely because the four undergraduate mentors were from Bronx families, just like the scholars, said Ball.

“They were able to relate and tell them, ‘College is a real option for you; This is what collegiate behavior looks like; This is how you break down a syllabus,’” he said.

Ball added that the program not only prepares students for college coursework and culture but also introduces them to fields of study that will be available to them, like sociology. This makes the program a great recruiting tool, he said.

Jost’s syllabus for the high schoolers was similar to the ones he prepares for his undergraduate students. In just two weeks, the teens were assigned dozens of articles and academic papers to read in preparation for the presentation deadline. With field trips and dorm room stays eliminated, Bell said the group focused on bringing in an array of weekly guest speakers on Zoom, including Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of African and African American studies; Maria Aponte, assistant director of diversity and global inclusion in Fordham’s Career Services; columnist David Gonzalez of The New York Times; and Vivian Vázquez Irizarry, producer/director of the acclaimed film Decade of Fire, which focuses on the 1970s South Bronx.

“We were deconstructing tired old racist narratives about the Bronx and young people of color, and using this history and family interviews to reconstruct narratives that center on the experience of our students, their families, and communities,” said Ball. He noted that the scholars collected oral histories from family members and also learned about the borough from documentaries and the Bronx African American History Project.

Jost said that his sociologist’s penchant for collecting data and combing archives to examine the past was complemented by Ball’s business school instinct that the students should also present contemporary solutions to historic problems. It’s was a cross-disciplinary effort that both appreciated and hope to see more of, they said.

Debunking Myths

The scholars broke into four teams to conduct their community-based research for the July 23 presentation of their capstone project on Zoom. Viewing the presentation were local members of the community, government representatives, several lecturers from the program, and University faculty and staff.

One of the four presentations, focused on gentrification, was titled “The Replacers.” The scholars used interviews, lectures, news articles, and historic images to conduct their research. The city-wide quarantine limited who the students could reach out to. Scholar Harley Lopez, a rising junior at Manhattan Hunter Science High School, interviewed her grandmother who has been living in New York City for 30 years. Lopez’s interview provided scholars with a first-hand account of an emotional move from Brooklyn to the Bronx caused by increased housing costs. Student presenters said the interview helped them relate to how neighborhood bonds can be severed by rising rents.

For solutions, the team looked to community efforts by tenant associations that address displacement and advocate for residents, students said in their presentation. They referenced a successful 2018 tenants’ class-action lawsuit against New York City Housing Authority for lack of heat and hot water in housing projects during the winter of 2017-2018 as proof that tenant activism works. The scholars did not necessarily turn their backs on newcomers that come with gentrification, but they insisted on “community despite disparity” in their presentation. They suggested that newly built infrastructure, such as condos, include a designated space for cultural expression that could create “unity beyond physical barriers” between newcomers and longtime residents.

Lopez said the research project—and the history she learned—made her understand the importance of local narratives and the disproportionate influence the media can have.

“We live in the Bronx, we grew up here, but we have all of these outside influences that even affect how we see ourselves,” she said. “We deconstructed the phrase ‘black-on-black crime.’ These phrases that are used in the media make us think that we pose more of a danger to ourselves than the system does.”

She said the narrative that the Bronx is a dangerous place has infiltrated Bronxites’ perception of themselves and their borough. She noted that through the History Makers program, she learned about the relative freedom teens had while growing up in the borough in the 1950s and ’60s. Today, many parents, including her mother, perceive the borough to be too dangerous for her to freely go out and have fun with her friends.

“My mom barely lets me go out into my own community … and that really just goes to show how different things are now.”

She said the mentors helped her understand how to take control of the narrative to “debunk myths.”

Learning from the Learners

Jost said he’d like to see more participation from students who did not grow up in the borough.

“At this moment in time, why not?” said Jost. “We need a shift in our world view and to really own the fact that being located in the Bronx is a huge asset to the University.”

Ball said that he was impressed by how quickly the scholars grasped the material, though he added that in some ways it’s not too surprising considering it’s their story.

“They live the content and the social issues,” Ball said. “I’ve really never seen students this hands-on, but they were really into the granular details because these issues plagued them as well.”

Rising Gabelli School of Business junior Geraldo De La Cruz said he and his fellow mentors became each other’s “guardian angels.” He added that the first two weeks of getting acquainted with each other and the material were crucial.

“Any time that one of us needed an affirmation that they were doing a great job, we would do that for each other,” said De La Cruz.

Fariha Fawziah a rising sophomore at Fordham College at Rose Hill agreed.

“Our vulnerability was a big plus,” said Fawziah. “That first week we were sharing our roots, our families, and cultural values. Without that, we would not have had this connection at all.”

In the process, they learned from each other, said Fordham College at Rose Hill rising junior Emily Romero.

“What we learned was teamwork,” said Romero. “If I’m not an expert in one subject, someone else could be, and we just tried to combine all that together and mesh it for the scholars.”

Likewise, they left inspired by the young people they mentored.

“They were so aware of current social issues, activism, and protests,” said Fordham College at Rose Hill rising senior Benita Campos. “They were so passionate to make change.”

“They didn’t let the system define them,” said Fawziah.

]]>

“It was more important than ever to capture these stories, because the Bronx was probably one of most hard-hit boroughs out of the whole city—and those stories weren’t being told,” said Bethany Fernandez, a rising junior at Fordham College Rose Hill.

With support from Fordham professor Mark Naison, Ph.D., the founding director of the Bronx African American History Project, Fernandez and Veronica Quiroga, FCRH ’20, launched the Bronx COVID-19 Oral History Project.

Their goal is to document the stories of Bronx residents in audio and video interviews, giving people an opportunity to talk about how they and their families, communities, and workplaces have been affected by the pandemic.

“Recording these voices is of especial importance because the people of the Bronx, many of whom live on the edge of poverty and work in ‘essential occupations,’ have experienced one of the highest fatality rates from COVID-19 in the entire world. … If we are ever to change the conditions which have imposed such disproportionate pain on Bronx residents, we must allow them to speak for themselves,” the students wrote in a mission statement on the project’s website.

On July 7, Fernandez and Quiroga shared some of their work with Fordham alumni as part of a webinar organized by the Office of Alumni Relations. They were joined by the COVID-19 project’s faculty advisers—Naison, who established the Bronx African American History Project in late 2002 to fill in the gaps of African American history in the Bronx, and Jane Kani Edward, Ph.D., who has led the project’s immigrant research initiative since 2006.

COVID-19’s Disproportionate Impacts

Quiroga said that she, Fernandez, and rising Fordham College at Rose Hill seniors Carlos Rico and Alison Rini learned how to conduct oral history interviews through their work on the Bronx African American History Project. They drew on those skills to launch this COVID-19 offshoot so quickly and capture what’s happening in real time.

During the webinar, Quiroga and Fernandez shared clips from some of the project’s video interviews. In one, Bronx resident Maria Aponte, Fordham’s assistant director of diversity and global inclusion, said the pandemic and recent protests against racial injustice brought back traumatic memories of growing up in Harlem during the 1960s, when there were riots in response to incidences of police violence and housing and employment discrimination that disproportionately affected people of color.

“It really devastated me when they started breaking down the groups that were devastated the most [by COVID-19], which was the lower income, African American, Latino community, and it’s almost like a whole history of people just got wiped out,” she said. “My husband and I live near Montefiore Hospital, and the first early weeks, it was the nonstop ambulance sirens. … That for me was a trigger, because I was a kid during the riots in the ’60s, and I watched Harlem burn with my mother. … It just took me back to when I was 9, 10, 11 years old.”

Quiroga said that Aponte’s reference to COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on marginalized groups, including Black and Latino communities, as well as the elderly, underscores larger societal issues that need to be examined.

“I also felt that her perspective was a window into the collective trauma experienced by most Bronxites during the pandemic,” she said.

Bronx resident Marlene Taylor, a 1979 Fordham College at Rose Hill graduate who currently works as a physician assistant at the Ryan Chelsea-Clinton clinic in Manhattan, said she’s seen how the pandemic has continued to exacerbate disparities, particularly in health care.

“I believe strongly that those who are already underserved from a health-care standpoint feel more distressed because if they already had challenges with getting medication, food, housing, now there are more obstacles, now there are more challenges,” she said in a video interview for the project.

Trying to Provide Hope During a Pandemic

Another project participant, Maribel Gonzalez, the owner of the South of France restaurant in the Bronx, said that as an entrepreneur, she has faced the emotional and physical toll of trying to stay in business while trying to support her longtime customers and neighbors.

“It’s still a struggle because you don’t know if you’re going to be around the next day,” she said.

But despite her personal concerns about her business, Gonzalez has made it her mission to be there for her customers who are struggling.

“When I deliver to people, I see so much sadness, I see so much devastation, I see food insecurity, I see hunger … which we’re also trying to address as a restaurant, and I am giving pep talks,” she said. “I’m giving them encouragement. I’m their mother, I’m their sister, I’m their friend. I’m often the only person that they’ve seen in a long time, because they’ve been in their house and they’re people who are alone and they don’t have conversation.”

Gonzalez said she tries to stay positive through her faith, for herself and others, and believes “that the business will come back, that the community will come back, that the Bronx will come back.”

“I think that her words near the end encapsulate the stories we try to tell,” Fernandez said. “The story of a lot of Bronxites deals with resilience.”

The Growth of the Bronx African American History Project

The Bronx African American History Project has been documenting these stories of the borough’s resilience since 2002. During the webinar, Naison provided an overview of the project’s work, including the COVID-19 oral history project, as well as research papers, including one by Edward on African immigration to the Bronx, and books, such as Naison’s Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life in the Bronx from the 1930s to the 1960s (Fordham University Press, 2016).

He said the project highlights how the borough, defying the odds, rebuilt neighborhoods from the fires of 1970s and the crack epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s. The neighborhoods, with lower crime rates, saw community life flourish again and it became the location of choice for new immigrants to New York.

“The Bronx African American History Project started when I was approached by an archivist from the Bronx County Historical Society who told me that groups were looking [for information]about African American history in the Bronx and couldn’t find anything,” Naison said. “What I discovered was pretty amazing—500,000 people in the Bronx who were basically invisible.”

His first interview for the project was with a social worker, Victoria Archibald-Good, who talked for three hours about her experience growing up in the Patterson Houses, a housing project in the Bronx. While the project eventually came to be known as a place where crime and drugs were rampant, in the 1950s and early 1960s, Archibald-Good said it was a great place to raise a family, and it produced well-known talent, including her brother, Hall of Fame Basketball point guard Nate “Tiny” Archibald, who earned a master’s degree from Fordham’s Graduate School of Education in 1990.

“That defies all your stereotypes about the Bronx in the ’50s and also about public housing,” Naison said.

After that first interview, BAAHP grew, thanks in part to funding from the Fordham College at Rose Hill dean’s office, which allowed more student and professional researchers to join the project. BAAHP also began partnering with local schools to teach students about Bronx history.

“Learning all this about the Bronx, as a site of successful migration and cultural creativity, was something that was going to lift the spirits of students who had only been told negative things about the Bronx,” Naison said.

Within the first few years, Naison said newspapers had been regularly reporting on their work, and researchers from other countries, including Germany and Spain, also began reaching out, asking if they could come along. The project also began to bring guest speakers to Fordham.

Around this time, Naison said while out in the community, he and others began noticing a large West African presence in the Bronx. “We [saw]a lot of people in Muslim garb, and mosques and Islamic centers opening up, and we realized there is an African immigration story emerging in the Bronx.”

Highlighting the Contributions of African Immigrants

Edward, who is from Sudan and had studied Sudanese women living in exile in Uganda, joined Fordham in 2006 as a postdoctoral fellow and launched BAAHP’s African immigrant research initiative.

“We noticed there was a large number of Africans in the Bronx, and someone needed to study their history,” she said. “Their contributions were not studied well.”

The main objective of the project is to examine the conditions of African immigrants and migrants who came to the Bronx from 1985 to the present, and highlight their contributions to the borough, Edward said.

“[We wanted to] shift the discussion from simply assessing their needs and challenges that they face to looking at their contributions and achievements,” she said.

Their research has included interviews with immigrants from Ghana, Nigeria, Mali, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Burkina Faso, among other nations, which revealed a growing and diverse immigrant community that has enlivened neighborhoods where Jewish, Irish, Puerto Rican, and Dominican immigrants trod before them.

Naison said that the borough, throughout its waves of migration, has been a home for “cultural fusion,” particularly in the areas of music and food.

“The Bronx is this site where people mix their cultures and they create something new,” he said. “It makes this a lot of fun to study.”

While the history project allows for many fun moments, right now its focus is on documenting stories of both suffering and resilience related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fernandez said her goal with this project is to provide an accurate portrayal of the Bronx and its residents—and to counter “negative stereotypes and … extreme prejudices about the Bronx and what the borough is like” that she’s heard from people, including some within the Fordham community.

“The Bronx African American History Project tries to tell the stories of the people who live here. This is somebody’s home, this is a place that somebody loves, this is a place rich of culture and history just like any other place that you might think of,” she said.

Learn more about the Bronx COVID-19 Oral History Project at thebronxcovid19oralhistoryproject.com.

Video by Tom Stoelker, staff writer.

]]>“The idea is to inspire people to stay home, but also get to know more about the community that they’re situated within, and also to provoke a response from people and invite them to share their own experiences,” said Desislava Stoeva, a BIAHI graduate project assistant who spearheaded the campaign.

The Bronx Italian American History Initiative is an oral history research project that documents the lives of Italian and Italian American residents of the Bronx. Over the past four years, BIAHI project staff have pored over cataloged video and audio interviews throughout the 20th century and preserved their stories. They interviewed more than 40 members of the Bronx community and documented their stories in their digital archives, similar to what Fordham’s Bronx African American History Project has done for the Bronx’s black community. BIAHI staff, from faculty to undergraduate researchers, have presented their research in the U.S., Italy, and the United Kingdom.

Now that people are spending most of their time at home, BIAHI is sharing more of its stories with participants and donors online. In late March, the initiative launched the new social media campaign, marked by the hashtags #stayathomewithBIAHI and #restaacasaconBIAHI (the latter is the Italian translation of the first hashtag). Through its weekly content on Facebook and Instagram, the campaign ties together people from two countries that bore the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic—Italy and the U.S., said Jacqueline Reich, Ph.D., co-director of BIAHI.

“We’re really trying, even in these difficult times, to engage with multiple publics as we do our outreach from home,” said Reich, who is also chair and professor of the department of communication and media studies.

Full of personal and historical details, the social media campaign’s stories evoke nostalgia about the old Bronx and its residents. There’s Robert Menillo, born in 1923, who recalls when there were no cars on the street and Arthur Avenue vendors sold produce from streetside carts. There’s Joanna Bonaro, who remembers attending Easter Mass with her parents and “how big of a deal” it was to get the coveted chocolate egg. There’s a trio of cousins who reminisce over a restaurant meal that tasted just like their grandmother’s.

“I was eating in a restaurant in Buffalo, my son lives in Buffalo, and it was an Italian restaurant, I tasted the sauce and it was my grandmother’s sauce, I couldn’t believe it. I hadn’t had that taste and that feel in like 50 years … It’s funny the memories that food brings you,” Carl Calò said in a BIAHI social media post.

In the full interview, Calò talks about growing up in the Edenwald Houses, a housing project in the Bronx, and what it was like to be the son of a Sicilian immigrant who was a sanitation worker. Eventually, his family left the projects and moved to Long Island. But one family member made his way back to where their American roots began.

“There’s this story of return in that interview where the cousin talks about how he went back to Edenwald when he was a New York City firefighter in the ’80s or ’90s. He knocked on his old apartment door, and he got to go in and see the little hole where he used to keep his box of army men hidden in his bedroom floor,” said Kathleen LaPenta, Ph.D., co-director of BIAHI and a senior lecturer in the modern languages and literatures department. “This kind of attachment that they have … I remember being affected by that [while conducting]the interview.”

In addition to posting on social media, BIAHI shares audio versions of its interviews on its SoundCloud podcast channel and the complete set of video interviews on its new digital archive website. In early May, BIAHI staff will talk about its initiative at a faculty webinar for Fordham’s development and university relations team.

In the meantime, strangers across social media are responding to BIAHI’s new campaign.

“It was nice to see people not just liking a post, but responding to it. One of our participants shared that his parents would talk to him in Italian, but he would always respond in English,” said Stoeva, a Fordham public media master’s student who plans on becoming a communications strategist. “It was interesting seeing people saying, ‘Yes, that was exactly my experience with that’ or ‘I resonate with that.’”

]]>

Then, in sophomore year, one of his professors—Mark Naison, Ph.D.—learned of his worries and called a Fordham administrator in search of funding help. And that’s how Purnell became one of the scores of students who benefit every year from the UPS Endowed Fund, Fordham’s largest donor-supported scholarship fund and one of the oldest scholarship funds at the University.

Money was a real concern for Purnell and his family; his father was a New York City transit worker and his mother worked as a secretary at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The UPS funding award not only eased their financial worries but also gave Purnell new confidence to apply for external funding for his undergraduate and, later, his graduate studies.

“It just really motivated me,” said Purnell, a 2000 graduate of Fordham College at Rose Hill.

“I can remember just feeling very supported by the school, very encouraged to continue to pursue academics, and to do the best that I could in the majors that I had begun to gravitate towards.

“It was an indication that the studies that I was doing in the humanities were valued,” Purnell said. He later earned a doctorate in history at New York University, taught at Fordham, and worked as co-research director on Fordham’s Bronx African American History Project. Today he is the Geoffrey Canada Associate Professor of Africana Studies and History at Bowdoin College.

Purnell is one of hundreds of students for whom the UPS Endowed Fund has made a pivotal difference since it was established five decades ago. Without it, many would not have been able to attend Fordham at all.

Origins of an Endowment

The endowment emerged out of relationships among UPS officials and Leo P. McLaughlin, S.J., president of Fordham from 1965 to 1969, said Arthur McEwen, FCRH ’55, a retired vice president of human resources at UPS.

Father McLaughlin had gone to grammar school and high school with Walter Hooke, a civil rights and labor activist who was vice president of personnel at UPS, said McEwen, who reported to Hooke at the time. The company president, James McLaughlin, had gone to a Jesuit high school in Chicago, and his son was a Jesuit scholastic teaching at Fordham Prep, McEwen said.

Father McLaughlin invited the two UPS officials to dinner, where the talk turned to the undergraduate college that would soon open at Fordham’s new Lincoln Center campus, and how the University could foster more racial diversity among its students.

When the college opened in 1968, the first entering class included 55 minority students who benefited from a new scholarship funded by UPS’s philanthropic arm, the 1907 Foundation (later renamed the UPS Foundation), McEwen said.

Supplemented with further gifts from the foundation, the UPS Endowed Fund has grown to $18 million and currently supports 154 students at both the Rose Hill and Lincoln Center campuses.

In decades past, the fund has had other uses: It helped teachers in the South Bronx attend Fordham’s Graduate School of Education, for instance. It also supported an internship program for Graduate School of Social Service students at the South Bronx’s Highbridge Community Life Center.

Creating Opportunity for Students

Today, the fund provides the UPS Scholarship to a diversity of students who would not otherwise have been able to attend Fordham. And it often provides financial flexibility that transforms students’ experiences at the University; past scholarship recipient José Haro, FCRH ’00, was able to study in Mexico for a year, and also did well academically “because I actually had time to study” rather than work for money, he said. He estimated that the scholarship from UPS covered about 20 percent of his costs.

When he got to graduate school, he felt well prepared. “I can’t put a value on the education I got from Fordham,” said Haro, an assistant professor of philosophy at the Borough of Manhattan Community College. He earned master’s degrees at New York University and at the University of South Florida, where he also earned his doctorate.

For Adrienne Boykin, GABELLI ’09, the scholarship funding from UPS came at a critical moment in sophomore year. A first-generation college student, she had transferred to Fordham from a community college, drawn by the top-flight accounting program and the Jesuit education. But finances were always a big concern, and she was having doubts that she could afford to stay.

“I thought all the pieces were falling apart,” she said. “But when I was able to get this scholarship, I just felt such a sense of relief and joy.”

Upon graduating, she went to work for accounting giant PwC, or PricewaterhouseCoopers, having taken advantage of its recruitment relationship with Fordham. “It was a very good job coming out of college,” she said. “Being at another school, I’m not sure that I would have been able to have that specific access” to employment opportunities at the firm, said Boykin, who is now the director of finance and administration at America Needs You, a nonprofit that provides mentoring and career development support to first-generation college students.

Many current recipients describe the scholarship as an important piece in the financial aid puzzle that brought a Fordham education within view. Mia Kroeger, a sophomore from Roswell, Georgia, was considering many colleges until she visited the Rose Hill campus. She was awestruck, “and when I met the people, I realized this was the perfect place for me,” she said.

The UPS Scholarship brought Fordham within the realm of possibility. “It was a big relief,” she said. Being able to choose Fordham “was really, really exciting.”

]]>

It may be located squarely in the Bronx, but for a few hours on a recent Saturday night, Fordham’s McGinley Ballroom was transformed to a 1980s SoHo art loft.

It may be located squarely in the Bronx, but for a few hours on a recent Saturday night, Fordham’s McGinley Ballroom was transformed to a 1980s SoHo art loft.

The event, 120 Wooster St: A Celebration of the Life and Career of Frederick J. Brown, showcased art, jazz, diversity, and, most of all, a wonderful sense of community and appreciation for the late artist, who was the father of Bentley Brown, GABELLI ’17.

“I have never been an event like this at Fordham—where art, politics, and music are fused together with a huge crowd,” said Mark Naison, Ph.D, professor of African American History and a mentor to Bentley Brown.

Now a graduate researcher at New York University, the younger Brown said he wanted the evening to showcase the important contributions of his father and other artists of color from that period.

‘A Mulitculturalist Language’

“What I really want people to see is that what black artists were creating in SoHo was a multiculturalist language that goes beyond ideas of race, nation, and so on,” he said.

Frederick James Brown (1945–2012) was a New York City and Arizona-based American artist whose work engaged with American history, music, urban life, and spirituality.

Brown’s paintings of the early 1970s were large, bold abstractions based on the abstract expressionist tradition of the art department at Southern Illinois University. Brown settled in a loft in SoHo during the New York art renaissance of the 1970s and 1980s. There, he collaborated with jazz musicians like Ornette Coleman and Anthony Braxton.

Groundbreaking, Visionary Work

Attendees learned about the artist’s work and passions through a riveting introduction by poet and activist Felipe Luciano.

“I’m proud to have known him. I’m proud to have been in his presence. I’m proud to have met a genius, a visionary,” Luciano said. “For those of you here, whenever you bring up the topic of American aesthetics, bring up Frederick J. Brown.

“His art was groundbreaking,” he said. “Before Basquiat, before all of them, Fred was doing this stuff. From the abstract, from the spiritual, from the physical, from the cultural, from the sexual, and he put it all together, and it scared some of us. It scared people when Coltrane started his Sheets of Sound. It scares people.”

Luciano said he and Brown would have “huge” debates in the Wooster Street loft about the artist’s need for acceptance by the art class.

“Fred was as American as you can get, a black artist who wanted to be American. I adored him. But he stuck to his vision, his aesthetic. I was not myself convinced he needed to be out there. He tried everything to be validated by this aesthetic league. We would have dinners at his house, and I’d think, ‘Why are we catering to these suckers? You just paint!’

“But Fred knew something I didn’t know, that there a legitimacy in being validated by the art establishment. I would’ve liked to just talk, but I knew I had to get a master’s in order to teach,” Luciano said. “I wrote some of my best poems, watching him paint while listening to the blues.”

Inviting the Bronx Community

Naison said he first learned of the artist when the younger Brown wrote a 153-page senior thesis about his father for a class he was taking with him.

“It fascinated me,” he said. “Bentley, who also was a student worker for the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP), said why don’t we do a dance concert and art fundraiser for the BAAHP? I thought, What a great idea. I mean, we can always bring great jazz to Fordham but let’s bring visual arts at the same time. And, most important, invite the Bronx community.”

The event drew about 150 people, including students, friends of the artist, and members of the Bronx community. It also provided an opportunity for other students of Naison’s to gain experience in event planning and producing.

“We have a great student staff. I have seven undergraduate research assistants and one graduate assistant who all worked on this. It was a collective effort, but it was Bentley who made this happen.”

Morgan Williams, a Fordham College at Rose Hill senior, attended the event because she is a friend of Brown.

“But I didn’t realize his dad was an artist,” she said. “I knew Bentley was an artist, but now I see where he gets his inspiration from.”

As the Dale Fielder quartet played, the audience was focused on the music. But during breaks, they milled about the McGinley Ballroom. The space was filled with Frederick Brown’s paintings, giving it the feeling of a major art gallery.

As Naison looked around the room filled with students, alumni, friends, and family of the artist, he smiled and said he was proud. He said he’d point to events like this when talking to prospective students about Fordham.

“You’re going to get professors who take a personal interest in you,” he said he’d tell them. “You’re going to meet amazing people in the Bronx community, and you’re going to meet great fellow students and be a part of a community who will be there long after you graduate.”

Video by Dan Carlson

]]>

Folklorist and choreographer Martha Nora Zarate-Alvarez, who heads the Bronx-based ensemble, said the group’s lively performance represented the traditions of the Huasteco and Jalisco regions of Mexico.

“We wanted to showcase the importance of Mexican culture in the Bronx and traditional Mexican dance,” said Zarate-Alvarez, who was dressed in a multicolored tiered skirt. “Mexican culture is more than just mariachi music.”

Bronx Celebration Day was presented by the Bronx Collaboration Committee, a division of the Fordham Club, and co-sponsored by Bronx Community Board 6, Fordham University Commuting Students Association, Fordham Road BID, and the Office of the Chief Diversity Officer at Fordham University.

Fordham College at Rose Hill senior Michael Ortiz, a member of the Fordham Club, said the mission of the Bronx Collaboration Committee is to integrate the Bronx with the Fordham campus.Though last year’s inaugural Bronx Celebration Day was held in McGinley Center, organizers took this year’s festivities outdoors.

“Having this year’s event at the [entrance]of the campus where it’s visible and audible beyond the gates was important connection that we wanted to make,” he said.

In addition to supporting local vendors selling t-shirts, handmade jewelry, art, books, and other items, Bronx Celebration Day featured several local music and dance groups, such as Dominican performers Yasser Tejeda & Palotrév; Afro Puerto Rican ensemble Bàmbula; Italian percussionist-dancer-singer Alessandra Belloni; Honduran cultural music group Bodoma Garifuna Cultural Band; and Latin, funk, and hip-hop group Boom Bits.

“The local groups demonstrate the creativity and beauty of the Bronx,” said Rafael Zapata, Fordham’s first chief diversity officer. “The event is really a great way for students who aren’t familiar with the community to learn about the roots of the borough, and also to be affirmed and inspired by the music, dance, art, and culture.”

Wakefield resident Hoay Smith was selling graphic baseball caps and hard copies of Bronx Narratives, a magazine he helped to launch with Dondre Green, the magazine’s founder and creative director. He said events like Bronx Celebration Day invites those who aren’t familiar with the borough to see the community through a fresh lens.

“Our underlying goal is to reinvent the story of the borough and this event helps us to spread brand awareness,” he said.

Nearby, local artist Evelyn Ray of Parkchester was selling vibrant collages and paintings. The work highlighted her Puerto Rican and Bronx pride.

“This is my life, my passion,” she said pointing to a painting bearing the Puerto Rican flag. “I think of this event as my little pop-up shop.”

South Korean artist Sohhee Oh brought along her mobile communal art project called “The Golden Door.” The three-dimensional cardboard door had the American flag painted on the side panels. During the event, she asked Fordham students and local residents to write down where they were from on Post-it notes, which were then placed on the golden door.

“The project is for the immigrants of the Bronx, but I also wanted people at the event, who are not immigrants, to know that the project widens the meaning of what an immigrant is.”

Looking out at the diverse group of attendees who gathered in the lot, Fordham College at Rose Hill senior Abigail Kedik said Bronx Celebration Day has helped to deepen Fordham students’ relationship to different ethnic groups that continue to make their mark on the borough.

“We’re guests in the Bronx and we should be open to collaborating,” said Kedik. “This is a great experience that helps students learn more about the community that we are a part of.”

]]>To honor Fordham’s Bronx connection, the University will host its Second Annual Bronx Celebration Day on Saturday, April 21, with a focus on uniting the diverse cultures within the borough and bringing them together with Fordham and the surrounding communities. The event gives Fordham a chance to get to know its Bronx neighbors while also enjoying local performing artists and vendors.

This fun-filled day will be headlined by Puerto Rican bomba and plena collective Grupo Bámbula, Dominican musicians Yasser Tejada & Palotré, Honduran cultural music group Bodoma Garífuna Cultural Band, Italian percussionist-dancer-singer Alessandra Belloni, and other local Bronx performers. There will also be hip-hop and spoken word performances, Mexican folkloric dance, and more.

Several local artisans will sell original art, and community organizations such as Run for Fun International and the Bronx Children’s Museum will be on hand to discuss their services and offer several ways members of the Fordham community can get involved in life off campus.

And there will be food!

Campus Tours

The community is invited to take campus tours. Fordham has been serving the community for many years, and always looking to increase interaction and personal connections between the on-campus community and neighbors in the surrounding area. To this end, on Bronx Celebration Day, the University invites the community to take tours of the Rose Hill campus.

Register for a FREE Bronx Celebration Day event ticket here. Read our story about last year’s event. For more information, email Natalie Wodniak at [email protected].

Free Jazz Performance after Bronx Celebration Day

That same evening, the University is hosting a jazz concert featuring two of the Bronx’s finest jazz musicians: pianist and composer Valerie Capers and pianist/singer/composer Judy Carmichael. Both of these artists are great personalities and music historians as well as performers and will have great musicians backing them up.

This event is is also free and open to the public. It is sponsored by the Bronx African American History Project and co-sponsored by the Bronx Music Heritage Center. It will take place from 7 to 10 p.m. in the McGinley Center Ballroom. More information here.

]]>