“My research is trying to unlock our history and how white supremacy and racism have shaped U.S. foreign policy in Africa, in addition to how Africans themselves have understood their own policies,” said Osei-Opare, an assistant professor of history at Fordham who is originally from Ghana.

A historian who focuses on African and Cold War history, Osei-Opare studies the history of his native Ghana, particularly the Ghanian political economy, Black Marxists, and Africa-Soviet relations. He has written about race and foreign policy in several media outlets, including a recent opinion piece about anti-Black racism in Ukraine for The Washington Post—and in many academic journals.

Two Prestigious Research Positions

Osei-Opare was recently awarded two research positions that will help him to complete his first book, Socialist De-Colony: Soviet & Black Entanglements in Ghana’s Decolonization and Cold War Projects, which will explore Ghana’s relationship with the Cold War. Starting this August, he will begin a two-year research leave from Fordham. During the first year, he will serve as a Mellon Fellow for Assistant Professors at the Institute for Advanced Study’s School of Historical Studies. In the following academic year, he will serve as a scholar-in-residence at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. He plans on returning to teaching at Fordham in August 2024, after he finishes his book, which he called “one of the first history books to examine archival resources from West Africa, Russia, North America, and England.”

An Unusual Perspective on the Cold War

The roots of his research began with his childhood in South Africa. He met two doctors from the former Soviet Union who often mentioned Vladimir Lenin, the founding leader of Soviet Russia, the world’s first communist state, and Osei-Opare grew curious about him. In college, he enrolled in courses that focused on Eastern European history. At the same time, he studied the life of Kwame Nkrumah, the first prime minister and president of Ghana—and eventually, he reached a surprising conclusion.

“Nkrumah’s ideologies sounded very similar to Lenin’s economic policy and Soviet philosophies. I wrote my undergraduate thesis on that, and it just spiraled from there,” said Osei-Opare, who earned a bachelor’s and master’s degree in history from Stanford University and a Ph.D. in history from the University of California, Los Angeles.

Over the past decade, he has continued to study how Ghana sought to refashion its political economy out of colonialism’s extractive model, along with the nation’s relationship with the Soviet Union.

“Now my research has broadened to look at the Cold War in general and Africa’s role in shaping the Cold War. People in the West think of the Cold War as something solely between the U.S. and Soviet Union. But in fact, Africa was one of the big players. I’m trying to push Americans to think about the role that Africans have played in shaping what we know as the Cold War, in addition to the relationship between U.S. foreign policy and race,” he said.

A Shift in Student Understanding of African History

Since he joined Fordham in 2019, Osei-Opare has taught six courses related to his expertise and today’s world, including slavery’s long-lasting impacts and racism in the American educational system.

His course Understanding Historical Change: Africa, which is a requirement for all students, has improved many students’ knowledge of African history, said Osei-Opare.

“Many students come into the class without the best understanding of what Africa is,” he said. “Through this course, I have shown them how the idea of Africa as a wild, barbaric place is pervasive. I show them where these ideas come from, how Africans have fought back against these ideas, and why they still persist.”

In 2020, the United Student Government at Rose Hill awarded him the Beacon Exemplar Award for his excellent work as an educator. In 2022, he also served as the keynote speaker at Fordham’s Diversity Graduation ceremony for Black students.

But for all the recognition he’s received for inspiring students, he says that his students are often the ones who inspire him.

“I’ve come across some wonderful students at Fordham who have helped me think about my research and African history through insightful analysis and questions and whose own research interests have expanded my own expertise,” said Osei-Opare. “They have also challenged me to think about what it means to be a Black male faculty member at a predominantly white instituion higher ed institution and encouraged me to continue to push for an anti-racist institution.”

He recalled some of his most rewarding moments as an educator at Fordham. After the killing of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, several students wrote to him, thanking him for helping them to see things differently and discuss issues with a more educated perspective. And at the end of his course UHC: Africa, he said he saw a shift in his students, too.

“Before class began, I asked students to send me three words that come to mind when they think of Africa. At first, they submitted words like ‘dark continent,’ ‘safari,’ and ‘animals.’ At the end of the semester, new words popped up: ‘socialism,’ ‘Pan-Africanism,’ ‘Black consciousness,’ ‘colonialism,’” he said. “There was a shift in seeing Africa as a place where you go and see animals to a place where humans with ideas live and exist.”

]]>Smångs, assistant professor of sociology and anthropology, studied hundreds of lynchings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, focusing on those that were public and ritualistic. By defining white identity in terms of a threat that black people supposedly presented, these lynchings paved the way for repressive Jim Crow laws and, ultimately, for many inequities that are still with us, said Smångs.

In other words, lynching’s past is not fully past.

“It’s important to understand lynching, because it was not just an historical phenomenon. It has implications today,” said Smångs.

He took up this topic during graduate school at Columbia University after seeing that most sociologists treated lynchings as “undifferentiated” killings driven by economic competition between white and black people within the cotton-based economy of the South.

However, this view couldn’t account for the public spectacle and ceremonial violence, which would seem unnecessary if the killers were simply trying to eliminate someone seen as a troublesome employee or competitor, he said.

Smångs’ study included more than 600 lynchings—mostly of African Americans—in Georgia and Louisiana from 1882 to 1930. He divided them into two types, private and public, depending on their level of communal participation and support as well as ceremonial brutality.

Smångs’ study included more than 600 lynchings—mostly of African Americans—in Georgia and Louisiana from 1882 to 1930. He divided them into two types, private and public, depending on their level of communal participation and support as well as ceremonial brutality.

Private lynchings were typically carried out furtively by small groups, usually to settle interpersonal conflicts, and were sometimes publicly criticized by Southern elites. “They saw it as unwarranted, as conflicting with their interests in having social order,” said Smångs.

Public lynchings, however, were another story.

Before 1890, racism in the South reflected paternalistic views—held over from slavery times—of African Americans as intellectually and morally inferior and needing guidance from whites. Southern white leaders sought to co-opt black elites to say, “‘As long as the federal government and the North stay out of our business, we will foster cooperative race relations—that view of ‘cooperative,’ of course, on whites’ terms,” Smångs said.

But views changed when African Americans refused to play a subordinate part. Around 1890 a long-simmering racial ideology that cast black people as inherently threatening and biologically inferior came to the fore, Smångs said. “It seems to be a watershed point when it comes to public lynchings,” which he defined as being carried out by mobs of 50 or more and including ritualistic and symbolic elements.

The public lynchings became more common and more elaborately brutal around this time, Smångs said. Victims were tortured, mutilated, burned, or collectively shot. Sometimes signs were left near the site of the lynching. Sometimes the victim was killed at the scene of the crime ascribed to him, or confronted first with those who suffered the crime.

Meanwhile, public rhetoric—from journalists, politicians, and others—was clearly meant to achieve “a cohesive white community” through public lynchings, Smångs said.

“They said it’s the duty of all men to come together and punish these crimes, alleged murders, and alleged sexual assaults,” he said. “In the aftermath of some lynchings, newspaper editors and journalists and other people would say that the people of such-and-such locality did their civic duty to the white community.”

“They saw it as a community affair, and as a responsibility of whites towards other whites to come together,” he said.

He lays out his arguments in “Doing Violence, Making Race: Southern Lynching and White Racial Group Formation,” published in the American Journal of Sociology in March. He is expanding the article into a book to be published by Routledge, and will be presenting his research this summer at the American Sociological Association annual meeting in Seattle.

Smångs is departing from the view that lynchings expressed a social system that was already established. Rather, public lynchings cemented views as much as they reflected them.

“It’s not only that belief creates ritual, but rituals create beliefs,” he said. “These public lynchings had clear symbolic and ritual elements. They didn’t just express a collective white identity; they also forged it.”

They also created “a stigmatized collective group identity for African Americans, which included these notions of danger and threat,” he said.

This stigma fomented the passage of Jim Crow laws that disenfranchised and segregated African Americans, as well as the laws’ longer-term injustices that other scholars have documented, Smångs said. These include black people’s disproportionate rate of being imprisoned and receiving death sentences, and also problems in the areas where lynchings took place–like interracial homicide and the presence of white supremacist organizations.

These problems reflect what the scholar Khalil Gibran Muhammad has called the “condemnation of blackness” as dangerous and unworthy, a perception that was given “force and legitimacy” under Jim Crow, Smångs said.

“The ideas about race that are prevalent today are, for the most part, not the ideas that sustained slavery; they are the ideas that came about with the extremist white supremacy of Jim Crow,” he said. “It’s important to understand lynching because it impacted Jim Crow, and the legacy of Jim Crow is still around today.”

]]>

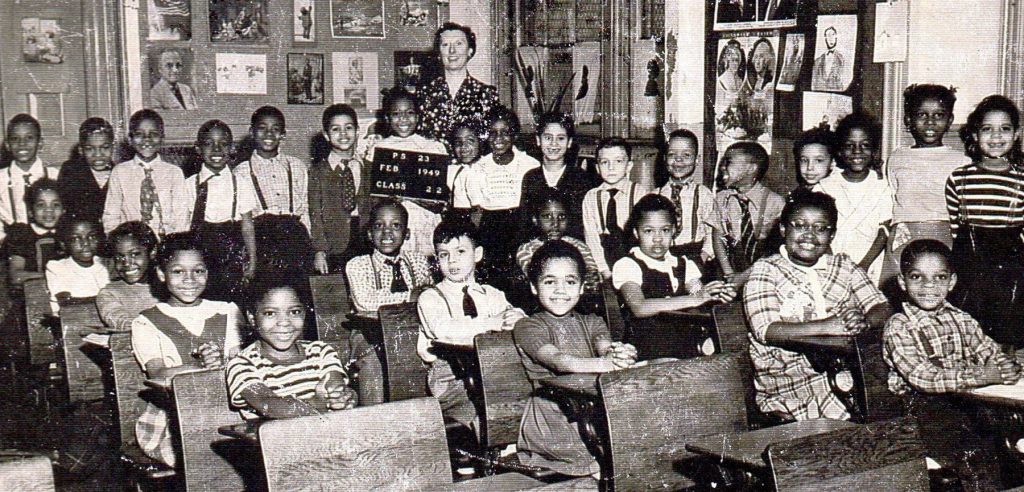

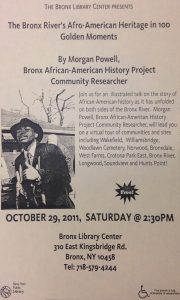

Just before his untimely death in 2014 at the age of 40, Powell gave part of his archives to Fordham. His book collection, known affectionately by friends as the Morgan Library, arrived shortly after he died.

The collection buttressed the late historian’s already substantial contribution to the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). The archives include material from his two primary interests: African-American history and local ecology.

Patrice Kane, head of archives and special collections at Fordham Libraries, said that despite Powell’s lack of academic credentials, he was familiar with and understood archival standards. She said what distinguished him from other amateur historians was that he wasn’t fixated on a particular period.

“Good historians are born, they’re not made,” said Kane. “He had the ability to make history come alive.”

In the oral history he gave for the BAAHP, the Jamaican-born Powell talked of a youth spent Harlem after his mother immigrated to New York. The family eventually moved to the Bronx. Though he was born abroad, he said he identified as an African American. He said he attended a good public grade school and avoided trouble in high school. However, he said his mother was unable to co-sign on a loan for the 17-year-old to go to college.

“I was too young to sign my own financial papers, and I was not able to establish independence because I wasn’t independent,” he said. “So that set up a whole series of events and circumstances that the whole rest of my life is going to be a consequence of, because that is a huge thing.”

Powell began educating himself and ferreting the stacks of the Schomburg Center, the Bronx Historical Society, and many used bookstores. Much of the material donated to Fordham is not from an original source, but the thousands of copies of receipts, photos, maps, and articles, represent diverse sources pulled together for the free tours he gave to Bronx residents.

“Not everyone thought of linking African-American history to the rivers, waterways, and parks,” said Mark Naison, PhD, professor of African and African American studies. “The tours he led were totally original.”

Along the way, Powell became as much of an activist as he was a tour guide. He lobbied for an African-American history collection at the New York Public Library’s Bronx Library Center and for a new master plan at Crotona Park. The latter effort included a letter, which he said he signed, “Your friend of mid-Bronx parks and critic of failed bureaucracy, Morgan Powell.”

His efforts still inspire visitors to the archive and fellow activists that knew him, such as Ajamu Brown, a Brooklyn activist working on food justice issues.

“We talked about the challenges of people of color who do this kind of work,” said Brown. “From him I learned about some of the important people who were involved, and (I learned) about thinking holistically about these problems.’’

As a devotee of history who never charged for his tours, there was little money left behind for a proper burial. But friends raised more than $17,000 to have his remains interred at the historic Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. Brown said that at a memorial service there was a “cross section of scholars, activists, and farmers.”

“It wasn’t like he wasn’t getting paid to do this,” said Brown. “We need more people who are willing to investigate this history and not just in the Bronx. Too many get written out of history.”

In the oral history project Powell was asked why he stayed on in the Bronx. His answer reflected his views on higher education.

“Perhaps [the reason]I care about the Bronx is maybe I was forced into empathy with the Bronx… Maybe it is because I could not get on that educational escalator, so that I could reach my own educational potential… [and become]someone who now has that masters degree in whatever I would have pursued… and gotten those various jobs out of college and moved out to Westchester or elsewhere as so many of my similar others have. Maybe that is why I am still in the Bronx. I think that’s an enormous part of it.”

]]>She remembers walking down 170th Street with her grandfather and collecting food samples from the storekeepers. She also remembers the years of being chased home from school by the white children, and the day her grandfather’s life was brutally ended, perhaps for no other reason than having been black.

These early years in the Bronx didn’t make her bitter; they made her resilient.

“My brother Rex and I made a pact that as long as we both lived we were going to be survivors,” said Bergland, a retired New York State prison lieutenant whose story is included in Fordham’s Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP) oral archive. “No matter what someone does to you, you have to survive. You learn to be strong.”

Bergland was 4 years old when her family moved to a predominantly Jewish neighborhood in the South Bronx. She and her brother were the only black children at PS 88, which often made the pair a target.

When Bergland was 6, her beloved grandfather was murdered for allegedly having an interracial relationship with a white woman.

“They never found out who did it. It was never investigated. He was just another black person,” Bergland said. “My memories of that part of the Bronx aren’t good ones.”

After her grandfather’s death, the family moved to 163rd Street and Tinton Avenue. The neighborhood was more diverse, but racism was still the reality. Bergland remembers being restricted to the take-out window at White Castle, because black people were not allowed inside.

The blatant discrimination never made sense to the little girl, and she found quiet ways to rebel.

“I remember the separate water fountains in Sears that said ‘colored only’ and ‘white only.’ I wanted to see what would happen if I drank out of the white fountain,” Bergland said. “By the grace of God, nothing happened. And the water tasted the same.”

Working for justice

Photo by Dana Maxson

Her keen sense of justice together with an early encounter ignited a lifelong passion for law enforcement. One day, a cousin of Bergland’s robbed a bank on Prospect Avenue and absconded to the Berglands’ house on Tinton Ave. It didn’t take long for the authorities to track him down.

“I was the one who answered the door. I opened it and there were two gentlemen from the FBI standing there. They showed me their credentials, and I was so impressed!” she said. “I decided then that I wanted to go into the FBI.”

At that time, there was a height requirement for women who wanted to be special agents, Bergland said, so she found other trails to blaze in the law enforcement field. She began her career as a store detective for E. J. Korvette department stores, working undercover to catch employees who were stealing. In 1962, after 10 years, she transitioned to the corrections department to work in prisons such as Bedford Hills and Sing Sing.

“I wanted to be able to tell my grandchildren stories,” she said. “And I got plenty of stories to tell them from Sing Sing.”

However, it was an experience at Great Meadow Correctional Facility in Comstock, New York that has stayed with her the longest. On her first morning there, she encountered a young black inmate scrubbing the floor. He paused when he saw her.

“He looked up at me and said, ‘Lieutenant, can I ask you a question?’ And I said yes. And he said, ‘Can you stop them from calling us [the n word]?’ I asked him who called him that, and he said everyone did, including officers,” Bergland said.

“That kind of hatred was much more than anything I’d received when I was a little girl. They didn’t call us names—they just didn’t like us,” she said.

“That kind of hatred was much more than anything I’d received when I was a little girl. They didn’t call us names—they just didn’t like us,” she said.

Bergland, who was the prison’s first black female watch commander, approached the captain with the inmate’s concern. Her advocacy launched a conversation about the racially charged language being used. Eventually she prevailed—the staff was prohibited from using racial slurs.

“It was good to feel that I was helpful in some way to them,” Bergland said. “After that, the black inmates would see me and say ‘Hi Ma,’ and I would say ‘Hey son.’”

Preserving black history

She retired after 30 years, but remains active in the Bronx community and with her family—one daughter, four grandsons, and a newborn great-grandchild. She is a deacon at the Community Church of Morrisania and was instrumental in creating an African-American pictorial museum, a collection of images and artifacts from her mission trips with the church to West Africa.

“People need to be taught. Black history should not be forgotten. You have to know where you came from so you know where you’re going,” said Bergland, who recently celebrated her 80th birthday.

“It’s not just black history; it’s all of our history.”

]]>The archive, made available through the Department of African and African-American Studies and Fordham Libraries, consists of downloadable audio files and verbatim transcripts of interviews conducted by researchers from 2002 to 2013.

“This took years of incredibly hard work,” said Mark Naison, PhD, professor of history and African and African-American studies and principal investigator of the project. He said that the transcriptions were completed over the past two years by Fordham undergraduates, with the exception of a handful of people from outside of Fordham, who helped when interviews were conducted in French.

Those French-language interviews represent the organic nature of the project as it grew from an American focus to one that encompassed recent immigrants from Africa—both Anglophone and Francophone. Naison said that the African diaspora in the Bronx also included Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latino immigrants.The archive also includes interviews with white families who stayed on as neighborhoods went through demographic transformations. Naison said that in the 1940s and 1950s, the Bronx was “incredibly diverse” as the borough transformed. White flight didn’t happen in a flash.

“For about 20 years the Bronx had a very unusual mix,” said Naison. “The transformation was a much slower process than people realize. We captured that experience.”

“For about 20 years the Bronx had a very unusual mix,” said Naison. “The transformation was a much slower process than people realize. We captured that experience.”

The racial mixing inspired a musical history, too, which has become an overarching theme that evolved through the interviews, said Naison. Similarly, as one oral account led to the next, it became obvious to the researchers that they should include the wave of African immigration, which by the 21st century had grown to be one of the largest in the Western Hemisphere.

In 2006, Sudanese native Jane Edward, PhD, a clinical assistant professor in the African and African-American studies department, joined the oral history project to engage the growing African community. She and Naison went to events, schools, and organizations, eventually gaining the trust of the communities. Edward, an ethnographer by training, had to veer from the established protocols of the project, creating separate questionnaires and release forms tailored to the community concerns, as issues of undocumentation left some afraid to speak.

“It ties to my own experience as an immigrant from South Sudan,” said Edward. “It is also a contemporary history, so it changes all the time.”

The project moved from gathering oral history to organizing and uploading the transcripts and recordings, with an eye toward preserving the borough’s history for the long haul, said Damien Strecker. A doctoral candidate in history, Strecker worked with Fordham Libraries to archive the project.

“You don’t want them collecting dust,” he said. “You want them available for scholars, but also you also want a kid in a Bronx middle school or high school to be able to Google them and find them.”

Even with the technical issues he faced in creating the archive with such large files, Strecker said he still was pulled in by the personal histories.

“The stories can latch on to you,” he said. “The real gold is the average working person sharing his or her life experience.”

One end result of putting the archive online for the public may be to raise Fordham’s profile in the Bronx. Project participant Andrea Ramsey, FCRH ‘86, said that when she was growing up she often went to the Bronx Zoo and the New York Botanical Gardens near the campus, but she didn’t know much about Fordham “other than that it was a Catholic organization or school.”

“I love Fordham, and I went here as an adult,” she said. “But when I was growing up I wasn’t aware of [it].”

Bob Gumbs, a local historian and project organizer, said he knew of very little in terms of contact between Fordham and the residents of the south Bronx before the project got underway in 2002.

“Fordham was a world away,” he said. “So I think this project has given the University a new identity in a positive way.”

]]>

On display are 34 photos of members of the “Harlem Hellfighters,” the first all-black regiment to serve with the American Expeditionary Forces overseas.

The 369th Infantry Regiment, as it was formally named, fought in both world wars and broke ground for African Americans seeking to serve in the U.S. military. The display features photos of the members taken between 1939 and 1945.

During World War I, the regiment was attached to a French army unit because many American soldiers refused to serve with African Americans. By World War II, however, the regiment had been brought under the umbrella of U.S. forces.

During World War I, the regiment was attached to a French army unit because many American soldiers refused to serve with African Americans. By World War II, however, the regiment had been brought under the umbrella of U.S. forces.

The Hellfighters comprised 1,800 men from the five New York City boroughs, with the core group coming from Harlem. Among the more famous Hellfighters were Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, tap dancer and actor; and Regimental Commander Benjamin O. Davis Sr., the first African-American general in the U.S. armed forces.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the unit was sent to guard the Pacific coast and then sent on to Hawaii to help defend against further air attacks.

In Hawaii, many of the servicemen felt more welcomed than in the United States because the native Hawaiian population was itself racially diverse. Outside of their own country, they could see themselves as combat soldiers first, according to an article in The Journal of Social History.

They still faced the residual racist ideas from the mainland, however, the article said. One story circulating on Oahu had the Hawaiian natives trying to be kind to the servicemen by putting pillows on their chairs at a gathering. The natives had been told that black men had tails and figured that sitting on hard chairs would be uncomfortable for them.

By 1944 the first Hawaiian NAACP was established in Honolulu. Following the war, many black servicemen decided to remain on the island.

The somewhat obscure collection came to the attention of Patrice Kane, head of archives and special collections for Fordham Libraries, through a vendor. Kane was able to purchase the collection with the help of Fordham’s Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP).

While the photos capture a critical piece of American history, the soldiers in the photos still remain unidentified; Kane hopes that getting the word out about the collection will change that.

“Somebody’s dad is in these pictures. I would love for their descendants to come forward and identify them,” she said. “They are significant to our history project because they represent a slice of New York City’s African-American history of which very little has been written.”

]]>

Glover participated in a panel discussion following a screening of the feature film Tula: The Revolt, the story of a 1795 slave uprising in colonial Dutch Curacao, in which Glover also starred.

He emphasized the role of education in shaping a generation that not only understands the lasting impacts of slavery but which is prepared to act to achieve justice for those still oppressed.

“Education defines what information we receive and our capacity to use that information,” Glover said. “Are we simply accepting ourselves as consumers and believing that access to information gives us power?

“It’s how you use the information, whatever information you have access to, that gives you power.”

The event was co-sponsored by the UN’s Remembrance Programme of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the UN Academic Impact (UAI), and Fordham’s School of Professional & Continuing Studies, Department of History, and the School of Law.

The remembrance program was initiated in 2008 to help raise awareness about the dangers of racism and prejudice today.

Panelist Yuko Miki, Ph.D., assistant professor of history at Fordham, said that while film is a powerful tool to help foster understanding of history, viewers should evaluate films with critical eye same as a historian would with any source.

Miki said Tula’s representation of the enslaved people in the Curacao revolt aligns with recent scholarship.

“You see the enslaved people not as people who are just passively working. They’re shown as people with intellectual lives, who understand the law and global politics. And they have a very complex idea of what freedom might mean,” she said.

Panelists commented that slavery is not just a footnote to humankind’s global history but a practice that shaped the many aspects of modern society and its economy.

“We would not have a United States were it not for enslaved people’s labor.

The same is true of any ‘great nation’ you might think of in this world,” said Natasha Lightfoot, Ph.D., assistant professor of history at Columbia University.

Glover said the impact of slavery is far from over. While slavery was an integral part of the U.S. economy for far more than 200 years, it was only abolished 150 years ago.

In his role as a UNICEF goodwill ambassador, Glover has worked with governments in Latin America to bring to light how descendants of victims of slavery continue to suffer disproportionate economic and societal injustices. He said he hopes citizens and political leaders can “reimagine” how a democracy can address those long-reaching injustices.

Helping people connect with the stories of real individuals, like Tula, are vital in creating an environment where advocacy and change can occur, he said.

“As we give more voice to these stories, it allows us to position ourselves in a world where the first argument for the lack of government response, or reparations, is a scarcity of resources,” Glover said.

“As we bring light to these stories, they bring understanding. But understanding cannot flourish unless there is also compassion,” he said.

“Once we understand the connection line, maybe we’ll start the healing process. We have to demand that. We can’t just simply think that we’re beyond this.”

]]>On Tuesday at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus, his story will be told.

Tula, The Revolt, a 2013 feature length movie about those momentous and tragic days, will be shown at a special screening that will be attended by Danny Glover, who stars in the film.

Glover, an actor, director and political activist best known for his roles in films such as The Color Purple, Witness and the Lethal Weapon series, will sit afterward for a discussion about the film.

Tuesday, September 9

5:45 p.m.

Costantino Room, Fordham School of Law, Lincoln Center campus

The evening is sponsored by the United Nations Remembrance Programme of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the United Nations Academic Impact (UAI), and Fordham’s School of Professional & Continuing Studies, History Department and Fordham School of Law.

RSVP is required: bit.ly/TULA_Fordham

For additional information, visit www.un.org/en/events/slaveryremembranceday

Contact: Patrick Verel

(212) 636-7790

[email protected]

During the pre-Civil War era, much of the North and its institutions worked for the emancipation of all slaves and the end to racial segregation. In his latest book,Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), MIT history professor Craig S. Wilder, Ph.D., FCRH ’87, does much to expose another side of history. He documents very real ties between Northern universities—the Ivy League in particular—and the perpetuation of a slave economy and racial inequality.

Wilder returns to his alma mater for a lecture on the Rose Hill campus on Thursday, Feb. 20 at 6 p.m. in the Flom Auditorium of William D. Walsh Family Library, titled “How Slavery Shaped Schools: Northern Opposition to Black Education in Pre-Civil War America.”

His lecture will focus on African Americans’ struggle to gain access to higher education, including attempts to build colleges and to integrate existing schools.

“Cities like New York had deep economic ties to slavery in the South and the West Indies, a fact that influenced their politics and created a deep anti-abolitionist tradition,” said Wilder. “These regions saw extraordinary violence and resistance—mob attacks, assaults, and court proceedings—to stop the higher education of African Americans.”

A native of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, Wilder earned his undergraduate degree in history at Fordham before moving on to Columbia University to attend graduate school and earn two masters’ and a doctoral degree. He worked in the Bronx as a community organizer after graduation.

The lecture is sponsored by the Dean of the College of Fordham at Rose Hill and isopen to the public.

Wilder discussed the book on NPR this past September.

]]>