Traina delivered her talk, “This Year’s Model: Updating Dulles,” after being installed as the second Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., Chair in Catholic Theology. The chair was established in 2009 in honor of Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., who was the Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society at Fordham from 1988 until his death in 2008. The first holder of the chair, Terrence Tilley, Ph.D., professor emeritus of theology, was also present.

Traina began by noting that Cardinal Dulles’ groundbreaking book, Models of the Church, (Penguin Random House, 1973) was a perfect example of his “creative approach to ecclesiology,” because its use of models instead of strict definitions offered a path forward.

Traina began by noting that Cardinal Dulles’ groundbreaking book, Models of the Church, (Penguin Random House, 1973) was a perfect example of his “creative approach to ecclesiology,” because its use of models instead of strict definitions offered a path forward.

“His vocation was to help ordinary Christians understand and be inspired by the church so that we could embody it. Divided over gender and sexuality, abortion, racism, war, economics, and even sacraments, we need his wisdom now more than ever,” she said.

Dulles’ book described the church in terms of different models: an institution, a mystical communion, a sacrament, a herald, a servant, and a community of disciples. It was published right after the conclusion of Vatican Council II, which, Traina said, “let a thousand ecclesiological flowers bloom,” and encouraged Catholics to think about different ways of communing with God.

To the many ideas put forth about the church during Vatican II, she said, “Dulles replied that we should run toward multiplicity, not away from it. Because the church is a mystery—a graced reality beyond our full experience or knowledge in this life—only by embracing many simultaneously true visions of the church could we even begin to capture the church’s full reality,” she said.

The Woman by the Well

Traina said that during his life, Dulles knew that his own ideas—groundbreaking as they were at the time—would need to evolve. Building on his work, she suggested that an image of a Samaritan woman meeting Jesus in the Gospel of John, when seen through the lens of queer and feminist theology, inspires a vision of inclusiveness that the church aspires to but fails to live up to.

In the story, the woman was Jewish, as Jesus was, but as a resident of Samaria, she would have been eyed with suspicion by residents of Jerusalem. In the story, Jesus stops in the town and encounters the woman who, by virtue of being alone at noon, must be someone of “ill-repute.”

He offers her “living water,” in exchange for a drink from the well, but it is not until he tells her that he knows about her five husbands and her lover that she recognizes him as a prophet. Traina noted that womanist scripture scholar Wil Gafney has said that this is where “Jesus shows up in the place where private lives become public fodder…. where those who have been stigmatized and isolated because of who they loved and how they loved, thirst.”

“Jesus welcomes all whose loves the world shames,” Traina said.

What’s also relevant is that for a time, Samarians had worshiped the gods of five foreign tribes, even though, as the woman explains to Jesus, they firmly expected the Messiah. His knowledge of her “five husbands” is what lets him pass her test, proving he is the messiah.

“The question is not whether the Samaritan woman is worthy of Jesus, but whether he is worthy of her,” Traina said.

In addition to showing that a person who is “only a lay person” can be theologically sophisticated, Traina also noted that the woman points out that Samaritans worship on a mountain, and not in Jerusalem, as the Orthodox Jews do.

“Jesus could have responded by saying, ‘That’s OK, we’re inclusive, from now on you can worship with us in Jerusalem; we welcome you to join us there.’” she said.

“Instead, he says, ‘Woman, believe me, the hour is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem. … the hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshippers will worship the Father in spirit and truth.’”

John’s message, she said, is that Jesus preserves diversity: Samaria does not have to follow the style of Jerusalem to be faithful, but neither does Jerusalem have to follow the style of Samaria. The same goes for Christians of all varieties today.

She noted that the time is right to reexamine Dulles’ models, because in recent years, American Catholics have given into a temptation that Dulles himself emphatically condemned, “sliding from acknowledging the church’s institutional dimension to equating church with “institution”—at the expense of its other essential characters.”

This has led to clericalism, which places all power in the hands of clergy; juridicism, which leads to excessive policing of who is “in” and therefore eligible for the benefit of the sacraments; and triumphalism, which Dulles wrote “dramatizes the Church as an army set in array against Satan and the powers of evil,” Traina said.

Catholics can look to the example of the woman at the well as they wrestle with the ways that race and sexuality get in the way of true inclusivity, she said.

“With respect to God, the distinction between Jerusalem and the mountain, between Israel and Samaria, has dissolved, for the Samaritans but also for the Jews in Jerusalem. There is no inside, no outside. Rather, there is just “spirit and truth.”

]]>On April 8, colleagues, friends, and associates who knew him best closed out the University’s yearlong celebration of the cardinal with an evening of discussion, prayer, and fellowship.

“The Apologetics of Personal Testimony: A Celebration of the Life and Faith of Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J.,” featured a panel discussion, a Mass and a dinner reception on the Rose Hill campus, Cardinal Dulles’ home for 20 years.

The day began at Tognino Hall, where Michael C. McCarthy, S.J., vice president for Mission Integration and Planning at Fordham, moderated a panel discussion featuring Michael Canaris, Ph.D., GSAS ’13, assistant professor at the Institute of Pastoral Studies at Loyola University Chicago, Anne-Marie Kirmse, O.P., former research associate for the McGinley Chair in Religion and Society at Fordham, and the Most Reverend James Massa, auxiliary bishop of the Diocese of Brooklyn.

Sister Kirmse focused on Cardinal Dulles’ journey of faith, from his early years in a deeply religious Presbyterian household to his casting off belief in God in high school and first two college years, to his conversion experience and his search for a church in which to practice his faith.

Cardinal Dulles was educated at Choate Rosemary Hall and Harvard University, and his family included a father who became secretary of state (Washington Dulles International Airport is named for him) and an uncle who became head of the CIA. He converted to Catholicism and went on to become the first American who was not a bishop to be named a cardinal. That same faith, she said, sustained him in the time of declining health in the years before his death.

Canaris as well picked up on that suffering—which he saw first-hand as Cardinal Dulles’ last doctoral student—speaking about “the crucible of torture in his last months.” In the end, Canaris, who is editing a volume based on papers on Cardinal Dulles delivered during events at Fordham this past year, said Cardinal Dulles was like the tested man in the Letter of James.

“Blessed is a man who perseveres under trial; for once he has been approved, he will receive the crown of life which the Lord has promised to those who love Him,” he said.

Bishop Massa recounted Cardinal Dulles’ long engagement with ecumenical dialogue, as well as the cardinal’s growing disappointment with how that dialogue was conducted, and where it was headed. While he stressed that Cardinal Dulles never reversed himself on the subject and “personally stood by all the ecumenical statements he had ever signed,” he said Cardinal Dulles believed “the ground had shifted” since early years after the Second Vatican Council and said a new term for this new landscape was needed.

“Avery gave it a name: ‘Mutual enrichment by mean of personal testimony.’ That focus on the witness of one’s Christian life became a motif of Cardinal Dulles’ later years, and was powerfully testified to by his final illness,” he said.

A Mass of remembrance concelebrated by the Jesuit community of Fordham followed at the University Church. Bishop Massa served as principal celebrant, and Patrick J Ryan, S.J., the Lawrence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society, delivered the homily.

At a dinner reception at Bepler Commons, Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, recalled Cardinal Dulles’ humble nature, noting that after he was elevated to Cardinal in 2001, he pointedly declined the honorific “Your Eminence” in favor of the traditional “Father.”

Cardinal Dulles was also close friends with Edward Cardinal Egan, Archbishop of New York, he said, and when his health started to fail him in his later years, Egan visited him often and offered him a final resting place at St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

“Dulles flatly told him ‘no.’ After some back and forth, he explained his reason: he wanted to be buried next to his Jesuit brothers,” Father McShane said.

“Avery Dulles was buried next to man a who taught high school math—a good guy.”

The evening was sponsored by the Spellman Hall Jesuit Community, the Office of the President, the Office of the Provost, the Office of Mission Integration and Planning, and the Center on Religion and Culture.

—Additional reporting by David Gibson and David Goodwin

[doptg id=”145″] ]]>

The words of renowned theologian Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., continue to inspire a generation of religion scholars. And it was conflict and dialogue among theologians that resulted in some of his important work.

Elizabeth Johnson, C.S.J., a long-time colleague to Dulles, the first American Jesuit ever to be named a cardinal, delivered a keynote on the “fluency of interpretation” of his thought at Dulles at 100, a recent celebration of his work and legacy at Fordham.

She began with Models of the Church, a book Cardinal Dulles wrote in 1974, after the Second Vatican Council, when conflict began to swirl among theologians as they debated different understandings of the church.

“Avery took this as a sign of vitality,” said Johnson, distinguished professor of theology emerita at Fordham. “His systematic mind created a way forward.”

In the book, Cardinal Dulles studied the writings of contemporary Protestant and Catholic ecclesiologists and laid out six major approaches, or “models,” through which the church’s can be understood: as institution, mystical communion, sacrament, herald, servant, and, in a recent addition to the book, as community of disciples.

“In this book, he showed how each these models had its own strengths, and how each also had its weaknesses. No one is sufficient to do justice to the full living reality of the church. So better to set up the dialogue among them and develop a theology that draws from the major affirmations of each,” she said.

It was not an ‘anything goes’ kind of approach,” Johnson said, but “it helped to wean ecclesiology from a one-horse sleigh way of traveling. The fluency of his way of thinking made theology even beyond ecclesiology more comfortable with pluralism, more at peace with diversity.

“To quote Avery, ‘We are as different from our medieval ancestors of the faith as the computer is different from the abacus.’ And that was written in the ’70s! ‘Thus, the religious language of one period needs to be revised for another,” Sister Johnson said.

Cardinal Dulles applied this approach not only to set topics in theology like ecclesiology, but to the teaching of the magisterium, she said, calling attention to his essay, “The Hermeneutics of Dogmatic Statements.”

The 15-page essay contained Cardinal Dulles’ six principles for interpreting doctrinal statements and a call for theologians to “refocus the message so that it speaks directly to the deepest concerns of people today.”

Johnson quoted the essay, calling attention to a great image he paints: “‘We cannot nourish people today with the stale fragments of a meal prepared for believers of the 13th, or 14th, or 16th century. We must articulate new theology with new doctrinal insights that will orient people to Christ in our day and relay the Christian message to ages yet to come.’”

She said she first read and discussed this essay under Avery’s tutelage in a graduate seminar, noting that it was something that influenced her own work and that she would go on to teach and discuss with new generations of graduate students.

“The fluency of his approach to interpreting theological differences and limitations of church teaching, an approach he later characterized in a different essay … as one of creative fidelity, opens a way to think deeply and critically about faith, and thus enables younger people to carry out the theological vocation with integrity,” she said. “Avery himself used this fluency broadly as some of his books made clear. He didn’t always carry it out. Avery was a complicated person. But this fluency, I think, is a rich part of his legacy.”

During the question and answer portion, Johnson was asked how “the Avery Dulles of later years” would look back on that essay. She said it was something the pair had discussed in his later years at Fordham.

“He never withdrew from these principles. They’re too deeply rooted in his own assessment of things. The practical way it would work out, though, is where we would differ; there would be differences.”. So if were interpreting a controversial issue, she said, he would feel he was still doing so using the principles laid out in the essay, “but with different assumptions about some people’s experiences that would lead him to a different conclusion. But, no, he never retracted. It was an interesting conversation. It was actually a painful conversation because I was writing things with which he would disagree, and so I’d say, ‘But you taught me how to do this.’ It does not change what he wrote and he stood by it.”

]]>

The daylong symposium, Dulles at 100, celebrated the late cardinal’s birth centennial and kicked off a yearlong reflection of his distinguished life and career.

Cardinal Dulles lived and worked on Fordham’s campus—first as a Jesuit scholastic from 1951 to 1953—and later as the Lawrence M. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society from 1988 until his death in 2008 at the age of 90.

“He was one of the giants of our intellectual and Jesuit communities. One of the finest theologians that the American church ever produced,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “He was an ambassador who built bridges. He was a gift to us.”

Raised in the Presbyterian Church and educated in Switzerland, at Choate, and at Harvard, Dulles converted to Catholicism and went on to become the first American who was not a bishop to be named a cardinal.

Of her storied teacher and longtime colleague, Sister Elizabeth Johnson, C.S.J., distinguished professor emerita of theology, said “a narrative genre has grown that we might call Avery stories.”

“There are many that I could tell of his endearing, informal interactions with students,” said Sister Johnson, who gave a keynote at the event. “Of his gracious presence as a dinner guest, of his game participation in liturgical dance, of his sense of humor at the most unexpected times, of his ecumenical passion, of his interventions and conferences or faculty meetings that occasioned laughter, frustration, or insight.”

Joseph Komonchak, Ph.D., professor emeritus of theology and religious studies at Catholic University of America, recalled a colleague who drove a car which was rumored to be handed down from his uncle, former CIA Director Allen Dulles.

“He drove that big whale of a car, that probably got nine miles a gallon, with a sticker that said, ‘Fly Dulles,’” he said.

The Elusive ‘Supermodel’

Father Komonchak said though he and Cardinal Dulles diverged theologically, Dulles always responded to an argument by complimenting the strengths of his opponent’s point of view before proceeding to dissect their thesis.

In his seminal 1974 book Models of the Church, Cardinal Dulles laid out six major approaches, or models, through which the church could be explained: as institution, mystical communion, sacrament, herald, servant, and, in a later addition to the book, as community of disciples, which attempted to encompasses the other five. The book became a standard text for many ecclesiology courses.

“He had a very modest view of systematic theology. You will recall that in Models of the Church, he used a somewhat disparaging term, supermodel, for a view that would try to combine the virtues of each of the five other models without suffering their limitations. And he expressed his skepticism that one could find any one model that would be truly adequate, for the church is essentially a mystery. Then, he said, we are therefore condemned to work with models that are inadequate to the realities to which they point,” he said. “I have long disagreed with that view of systematic theology.”

He said that the two exchanged lengthy letters on subject, until Cardinal Dulles came to believe the differences between the two to be so narrow that they were not worth debating.

“I think he also got tired of reading five page single-spaced small print letters from me,” he said.

The Migrant Church

Inspired by Dulles’ models, Peter Phan, Ph.D., Ellacuria Chair of Catholic Social Thought at Georgetown University, argued in his closing keynote remarks that the historical church as we know it would not exist without migrants, though global migration was barely on “Cardinal Dulles’ theological radar.”

In his talk, “Imagining the Church in the Age of Migration,” Phan ultimately concluded that “outside migration there is no salvation.” Riffing on the cardinal’s six criteria, Phan developed his own model by focusing on three points:

One: A good model of theology has to be both explanatory and exploratory (explanatory, meaning that a model can summarize what we know, and exploratory, meaning the model must discover new aspects of the problem). Two: A good model must incorporate experience of the church (“If it doesn’t resonate don’t do it”). And three: The model must somehow impact the spiritual mind; it has to inspire a spiritual awakening.

In his lecture about migration Phan hit all of those points. He began with shockingly raw numbers about migrants, which he counts separately from the 68.5 million refugees forced to leave their county because of war and violence last year. In 2010, there were 200 million people migrating for a variety of reasons, from floods to food shortages and violence, he said. But mass migration didn’t begin in the 21st century, he said.

“It has happened throughout history, just look at the slave trade in 19th century, 11 million Africans [faced]a form of forced migration,” he said. “Again, in the 19th century, the Great Migration from Europe brought 200 million people who voluntary moved to the U.S.”

He took issue with President Donald Trump’s assessment that United States is currently “infected” by migration. Eighty-five percent of refugees, not migrants, he said, have settled in the world’s developing nations, such as Turkey, Pakistan, or Uganda—not in Europe and not in the U.S, which recently limited the number of refugees it will accept to 30,000 for next year.

“We are not overrun,” he said.

He added that Western nations also need to remember that they are the primary cause of the crisis.

“Most of this is caused by the wars initiated by the U.S. It’s not just a social-economic issue, it’s a deeply theological and spiritual issue.”

Scholars Needed: Viewing Church History Through the Migrant Lens

He encouraged students in the room to consider writing the dozens of dissertations necessary to rewrite the history of the church through the lens of migration.

“Each of these migrations produces a new face of the church,” he said.

He noted that in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, Mass is celebrated in 42 languages and that a parish in the Bronx celebrates Mass in five languages. In Louisiana, the Catholic priests are mostly Vietnamese, he said.

Any decent history of the church, he said, examines the church through an immigrant’s lens, whether that be through the Irish, German, and Italian migrations of the 19th century or through the Central/South American and Asian immigrations of the 20th century.

He qualified that he was speaking of the church historically, not theologically, and of catholicity in the universal sense of the word, before concluding that “Outside of migration there is no American Catholic church, period! Outside of migration there is no catholic church at all,” he said.

“Without migration, the church as a whole would not exist as catholic. No migration, no catholicity.”

]]>

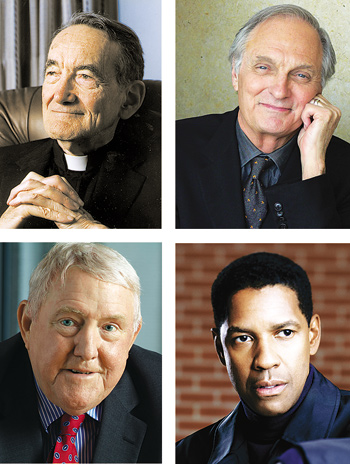

On Oct. 22, Fordham University welcomed four new inductees into the University’s Hall of Honor.

On Oct. 22, Fordham University welcomed four new inductees into the University’s Hall of Honor.

The Hall of Honor recognizes the accomplishments of alumni whose lives have exemplified and brought recognition to the ideals to which the University is devoted.

Avery Cardinal Dulles was a professor at Fordham from 1988 until his death in 2008. In his capacity as the McGinley Chair, he delivered a total of 39 lectures on subjects that ranged from the death penalty to human rights, and church reform. He was the first American theologian who was not a bishop to be appointed to the College of Cardinals.

Bronx-born actor Alan Alda is a six-time Emmy and Golden Globe Award winner who has also been nominated for an Oscar and a Tony. Generations of Americans remember him for his portrayal of Captain Hawkeye Pierce of M*A*S*H, and he is consistently rated one of the greatest television actors of all time.

On presenting Corrigan with his framed citation, Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, called his support for the University “magnanimous.” E. Gerald Corrigan, Ph.D., has built a career in finance that spans the public and private sectors, where he is equally respected for his deep knowledge and skill in assessing risk and establishing stability. Corrigan served as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York from 1985 to 1993, where his swift action following the 1987 Black Monday market collapse is widely credited with preventing further catastrophe.

One of America’s greatest actors, Denzel Washington has been a champion of theater education at Fordham. The two-time Oscar winner served on the University’s Board of Trustees from 1994 to 2000, and returns occasionally to the Lincoln Center campus to inspire theater students with his advice and success (see pg. 1). In 2011, he endowed the Denzel Washington Chair in Theater with a $2 million gift to Fordham, and made a $250,000 gift to establish a scholarship fund for theater students.

The honorees’ names will be inscribed in the main corridor of the administration building on the Rose Hill campus.

The University also inducted 21 new members into its Archbishop Hughes Society, recognizing them as men and women whose spiritual, financial and intellectual gifts have helped the University realize its mission.

— Nicole LaRosa

Msgr. Robert Brennan will be ordained

auxiliary bishop on July 25.

Photo courtesy of the Diocese

of Rockville Centre

A former student of the late Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., has been appointed auxiliary bishop of the Diocese of Rockville Centre, Long Island.

Rev. Msgr. Robert J. Brennan will be ordained along with bishop-elect Rev. Msgr. Nelson J. Perez by the Most Rev. Bishop William Murphy on July 25 at Saint Agnes Cathedral in Rockville Centre.

“I am honored and humbled that the Holy Father extended this call to serve the Lord in a new way,” Bishop-elect Brennan said. “I have learned so much from Bishop Murphy and I can never thank him enough for his kindness to me.”

Born in the Bronx and raised in Lindenhurst, Msgr. Brennan graduated with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and computer science from Saint John’s University and was a doctoral student in Fordham’s Theology Department in the early 1990s, before he was named secretary to the late Bishop John R. McGann in 1994.

Msgr. Brennan has served as vicar general of the Rockville Centre diocese for the last decade, and since 2010 has been pastor of Saint Mary of the Isle parish in Long Beach. In addition, he regularly celebrates the Spanish-language Mass at the Nassau County Correctional Facility.

He was named Honorary Prelate and given the title monsignor by Pope John Paul II in 1996.

The Diocese of Rockville Centre, which Msgr. Brennan will serve as bishop, covers 1,198 square miles in Nassau and Suffolk Counties and serves approximately 1.7 million Catholics.

Cardinal Dulles was Fordham’s Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society from 1988 until his death in 2008. In addition to holding this post, Cardinal Dulles was an internationally known author and lecturer, past president of both the Catholic Theological Society of America and the American Theological Society, and a professor emeritus at The Catholic University of America.

— Joanna Klimaski

On Tuesday, Dec. 14, his vast catalogue of scholarship will be the focus of a panel discussion at Fordham University’s Lincoln Center campus.

Avery Dulles and the Future of Theology will take place from 6 to 8 p.m. in the Pope Auditorium. The publication of Avery Cardinal Dulles: A Model Theologian (Paulist Press, 2010) by Patrick W. Carey will be the point of departure for a panel of theologians to discuss and debate the future of theology in light of Cardinal Dulles’s work.

They will look at both questions that Dulles asked and didn’t ask, the answers he gave as a potential foundation for future Catholic theology, and the significance of his method and style for addressing pressing theological issues.

The discussion, which is sponsored by the Fordham Center on Religion and Culture, will be moderated by Aristotle Papanikolaou, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Theology and Co-Founding Director of Fordham’s Orthodox Christian Studies Program.

The panel will feature:

Terrence W. Tilley, Ph.D., Chair, Fordham Theology Department and Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., Professor of Catholic Theology;

Phyllis Zagano, Ph.D., Senior Research Associate-in-Residence and Adjunct Professor of Religion at Hofstra University;

Robert P. Imbelli, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Theology, Boston College and a priest of the Archdiocese of New York;

Patrick W. Carey, Ph.D., Professor of Theology, Marquette University, and author, Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J.: A Model Theologian (Paulist Press, 2010);

Miroslav Volf, Ph.D., Director, Yale Center for Faith and Culture, and Henry B. Wright Professor of Systematic Theology, Yale University

The event is free and open to the public. RSVP at [email protected] or (212) 636-7347

—Patrick Verel

One day in 2002, Cardinal Dulles asked her to find an envelope in his files on which he’d written a reference. He jotted down the note while attending a talk in Washington, D.C. on a very warm day sometime in the 1960s. He wanted the reference for a lecture he was writing.

“The cardinal did his own filing because he felt that if he put something away, he’d know where it was,” recalled Sister Anne Marie, “and he remembered having put the envelope in his jacket, which he carried because of the heat.”

So she went to the files, of which there were many, with the clues at hand: Washington D.C. Warm weather. 1960s.

“I pulled a file from the ’60s, and Woodstock College (where the cardinal had taught). I went through each of the years, the spring months; and believe it or not, in the year 1967 there was an envelope, torn in half—on the back of which was a citation.

“It was true; his memory never failed him until he closed his eyes for the last time.”

Sister Anne Marie served as Cardinal Dulles’ research associate and executive assistant during his 20-year tenure as Fordham’s McGinley Chair. She helped the cardinal prepare speeches, organize his teachings and writings, keep up with correspondence and maintain his busy schedule of appearances.

Today, Sister Anne Marie is helping the staff of Fordham’s William D. Walsh Family Library curate a show on the late cardinal’s life and work. “The Papers and Memorabilia of Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J.,” runs through Dec. 23 in the library’s exhibition hall on the main floor.

It features more than 100 items of memorabilia from the cardinal’s personal archives, which he bequeathed to the library in 2003.

Included in the archival collection are books, research materials, manuscripts, correspondence, photographs, memorabilia, awards, decorations, honorary degree citations, the cardinal’s vestments and other materials.

University Archivist Patrice Kane estimates that there are a few thousand items in the Dulles archive.

Library Director James McCabe, Ph.D., said the collection is the library’s most valuable holding.

“If this archive were to be auctioned by Christies or Sotheby’s, it would surely be of interest to important research libraries like Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Stanford and others,” McCabe said.

“The show will reveal the dimension of his scholarship as the leading theologian of the 20th century in the United States, and some personal and family history. The Dulles family is an important family in the history of our country,” he said.

In her second-floor office at Faber Hall, Sister Anne Marie has spent a portion of her summer sorting out papers and artifacts for inclusion in the show. It is not unusual for a small bit of correspondence, or a boxed honorarium, to trigger a memory about the lanky beloved theologian who wore so many hats: soft-spoken professor in the Fordham community; fellow Jesuit; leading American theologian; and member of the Vatican elite.

One item on display is a small, tattered letter written in eager child script. The sentences run a bit crooked, but its content shows the signs of a thoughtful wordsmith. It is Cardinal Dulles’ first letter to Santa Claus, written when he was a young boy and most likely saved by his mother, Janet Avery Dulles. The content is politely tactical: “Dear Santa Claus, I send much love to you and I wish you to give me many Christmas presents, as you do always.”

Conspicuously, the entire upper case alphabet is printed artfully across the bottom of the letter below the signature.

“It made me curious why a child would print the alphabet on the bottom of a letter to Santa Claus, so one day I asked him,” recalled Sister Anne Marie. “He looked at me as if he was shocked that I hadn’t recognized his rationale. ‘Because,’ he said, ‘I wanted Santa Claus to know that I was a good boy and was doing my lessons!'”

A certain politeness and good finish existed within the Dulles family; thus the cardinal’s childhood included one year at an exclusive school in Switzerland and, eventually, an Ivy League education.

A sense of refinement is evident even throughout the family’s correspondence, said Sister Anne-Marie, especially within a telegram announcing Avery Dulles’ birth, sent from his grandfather to his father. “Your Son arrived at 7 this morning. Everything fine. Janet says come if convenient.”

“There’s that level of refinement from his upbringing,” Sister Anne-Marie said, “and there was a strong sense of decorum.” She recalled that, prior to becoming a cardinal, Father Dulles would typically wear an open sport shirt and Dockers, chinos or some brand of sports slacks during the summer.

“But he would always instruct me to be sure to tell him when the students were returning,” she recalled. “Then he’d put on a jacket and a tie every day. It would be 100 degrees in August, but he’d say, ‘I can’t disrespect the students.'”

With the office of cardinal, however, came a degree of pomp—at least with regard to dress. Pope John Paul II made Father Dulles a cardinal in February 2001; he is the only U.S.-born theologian appointed to the College of Cardinals who was not first a bishop.

Sister Anne Marie recalled a dinner not long afterward, held at New York’s Waldorf Astoria, to raise funds for Catholic universities. A number of Jesuits and nuns sat at a table sponsored by Fordham as Cardinal Dulles walked in dressed in a full-length scarlet watered silk cape or ferraiolo—a cardinal’s covering for special non-liturgical occasions.

“We all did a collective gasp,” recalled Sister Anne Marie, “because he was so tall, and that cape on him was astoundingly beautiful.”

The ferraiolo is on exhibit, draped over the cardinal’s scarlet-tripped cassock.

Among other things on display a French croix de guerre World War II cross of war, which naval Lt. Avery Dulles received for heroism; Cardinal Dulles’ white brocade mitre hat; his red silk biretta—which famously fell from his head as he embraced the Pope during his elevation—a typed letter to his parents explaining his conversion to Catholicism; his sterling silver birth cup from Tiffany’s; several photos from various decades of his life; and a display of original announcements of his 39 McGinley lectures.

Some 70 volumes of the cardinal’s books are also on display in several translations. Henry Bertels, S.J., the University’s cataloguer of rare books, singled out a signed copy of the cardinal’s first commercially published title, A Testimonial to Grace (Sheed & Ward, 1946), inscribed to his mother.

“It gives you a personal insight into the relationship that Cardinal Dulles had with his family,” said Father Bertels.

Sister Anne Marie hopes that the exhibit, which was staged with help from Bronxville Jewelers in Bronxville, N.Y. and All Dress Forms in Sumter, S.C., shows the many sides of a man that the Fordham community was privileged to claim, and yet whose scholarly and theological legacy is far-reaching.

But it was his close personal relationships that came home to her strikingly on the day of his burial when his niece, Ellen Dulles-Coehlo, sprinkled a handful of dust onto his just-lowered coffin and spoke to him.

“[Ellen] told him how much he’d meant to her father (his late brother John), to herself, and to the rest of her family,” recalled Sister Anne-Marie. “At that moment, I realized that the love Cardinal Dulles had for God, his family, his friends and colleagues, his Jesuit community, his students, and his country are an important part of his legacy as well.

“We will not see his like again.”

Revered by colleagues and students alike for his work ethic, modesty, gentility and sense of humor, Cardinal Dulles was referred to by fellow theologians as “the grand old man of Catholic theology today in the United States.” Cardinal Dulles began his connection with Fordham in 1951, while still a Jesuit in training, when he was appointed an instructor in philosophy. He left Fordham in 1953 to pursue theological studies in preparation for ordination in 1956. After graduate studies in theology in Europe, he undertook an academic and priestly career that spanned five decades and included professorships at the Jesuit school of theology at Woodstock College, the Catholic University of America, and several visiting posts at the world’s top universities and seminaries. In 1988, when he reached the retirement age of 70 in his post as professor of systematic theology at Catholic University, he returned to Fordham–35 years after he had left–to take up the McGinley Chair. Cardinal Dulles referred to his years in the McGinley Chair as the happiest and most satisfying of his life, pleased with the freedom that the position gave him to teach, to lecture and to assume visiting appointments all over the world.

“A man of prodigious intellect and great holiness, Cardinal Dulles devoted his entire life to the task of advancing the dialogue between faith and reason,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham University. “In the process, he enriched both the Church and the Academy with his wisdom and his warmth. Therefore, it is not at all surprising that he was the first American theologian to be named to the College of Cardinals.”

Pope Benedict XVI met privately with Cardinal Dulles at St. Joseph’s Seminary (Dunwoodie), in Yonkers, N.Y., on April 19, 2008, during the Pontiff’s pastoral visit to the United States. The private audience was a recognition of the Cardinal’s intellectual and moral influence as a Jesuit, a theologian and a writer. During the meeting, the Pope blessed Cardinal Dulles, and was presented with a copy of the Cardinal’s bookChurch and Society: The Laurence J. McGinley Lectures, 1988-2007 (Fordham University Press, 2008).

Avery Robert Dulles was born on August 24, 1918, in Auburn, N.Y., the son of Janet Pomeroy Avery and John Foster Dulles, who went on to serve as Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. His paternal uncle was Allan Dulles, a founding father of the CIA. His great-grandfather John W. Foster and his grand-uncle Robert Lansing both had served as U.S. Secretaries of State.

The Dulles family raised their son as a Presbyterian. He did his primary schooling in New York City and was educated on the secondary level in Switzerland and at Choate. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard College in 1940 with a concentration in history and literature. His senior thesis on Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, the Renaissance polymath, was published by Harvard University Press as the Phi Beta Kappa Prize Essay of 1940.

As a young man entering Harvard in 1936, Dulles had already abandoned his Presbyterian upbringing and considered himself an agnostic. However, exposure to the works of the great philosophers and to Catholic writers in his later college years led him to convert to Catholicism while a first-year student at Harvard Law School. In 1946, following service in the U.S. Navy during World War II, he entered the novitiate of the Society of Jesus in Poughkeepsie, N.Y. On account of his father’s high profile and his own uniqueness as an Ivy League-educated convert, Dulles’ priestly ordination in 1956 in the company of fellow Jesuits by Francis Cardinal Spellman (a 1911 Fordham graduate), celebrated in the Fordham University Church on the Rose Hill campus in the Bronx, was reported on the front page of The New York Times. After doctoral studies at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, Dulles was awarded a doctorate in sacred theology in 1960.

Dulles once described his decision to convert to Catholicism as reminiscent of the action of “one of those timid swimmers who closes his eyes as he jumps into the roaring sea.” He also declared that, on his entry into the Catholic Church, “I made a venture that appeared foolhardy in the eyes of most of my family and friends. As a vowed religious, I took up a career that would make no sense unless the Catholic faith were true.” In the account of his conversion, A Testimonial To Grace (1946, Sheed and Ward, reissued with an afterword, 1996), he wrote that, “Although I cannot rival the generous dedication of St. Paul and Ignatius of Loyola, I am, like them, content to be employed in the service of Christ and the gospel, whether in sickness or in health, in good repute or ill repute. … I trust that his grace will not fail me, and that I will not fail his grace, in the years to come.”

During his tenure at Fordham, Cardinal Dulles delivered 39 McGinley Chair lectures on theological subjects that were sometimes controversial, including the death penalty, John Paul II and human rights, and church reform. He was considered an American theologian well-versed in ecumenism and a voice for religious freedom, a centrist in Catholic theology. While he applauded the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, he also stressed the need not to undermine Catholic Church polity and the fundamental teachings of earlier popes and councils of the Church. In the last decade of his life he had been seen among his colleagues to have moved to the right, suggesting in 1998 a need for a “countercultural,” more orthodox Church, and calling for “doctrinal firmness” in the face of dissent on such issues as the ordination of women.

On February 21, 2001, Dulles was elevated to the College of Cardinals by Pope John Paul II on the steps of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Cardinal Dulles was one of three Americans honored that day, and the only one of the three who was not a diocesan bishop. This honor crowned his lifelong work as a Jesuit, a theologian and a writer. Commenting on the experience, Cardinal Dulles said, “I enjoyed it, but that’s not really what counts. I prefer to spend my time reading, thinking, writing, teaching. I’m not particularly made for ceremonies.”

Cardinal Dulles’ work as a theologian saw its high point following the reforms made by Vatican Council II, when he wrote his most influential work, Models of the Church, (Doubleday & Co., 1974). The book takes a look at Catholic ecclesiology through five theological models derived from themes enunciated at Vatican II, in order to offer a deeper understanding of how the various ways of thinking about the Church found in the Scriptures may prove relevant to the modern world.

“There were a few years after Vatican II when the church seemed to be asking people to look at different ideas, but I came to fairly traditional conclusions,” he said in a 2001 interview with Fordham Magazine.”Vatican II said we had to re-examine what is time-conditioned, but having done that, I think we came back to say the councils were right on.”

Cardinal Dulles’ writings included 24 books and more than 800 articles, essays and reviews on theological topics. The books include Models of Revelation (Doubleday, 1983), The Catholicity of the Church (Clarendon Press, 1985), The Assurance of Things Hoped For: A Theology of Christian Faith(Oxford University Press, 1994) and A History of Apologetics (Ignatius Press, 2005). He was the recipient of 38 honorary doctorates, and was awarded the Croix de Guerre by the French government for his liaison work with the French navy during World War II. He served as an editor and adviser on several religious publications, including The New Oxford Review and Concilium.

Cardinal Dulles served as the president of both the Catholic Theological Society of America and the American Theological Society. He served on the papacy’s International Theological Commission and was also a member of the United States Lutheran/Roman Catholic Dialogue. His other awards include the Cardinal Spellman Award for distinguished achievement in theology, the Boston College Presidential Bicentennial Award, America magazine’s Campion Award, the Cardinal Gibbons Award from the Catholic University of America, the Fordham Founder’s Award (2002) and the Newman Award from Loyola College in Baltimore. He served on the Board of Trustees of Fordham University from 1969 to 1972.

The Cardinal is survived by the children of his eldest brother, John W. F. Dulles, and sister-in-law, Eleanor Dulles: John Foster Dulles II, Edith Dulles Lawlis, Ellen Coelho and Robert Avery Dulles; nieces Janet Hinshaw-Thomas and Lilly Holt, and nephews Foster Hinshaw and David Hinshaw; cousins Allen Jebsen, Joanna Jebsen Cook, Tina Afokpa, Per Jebsen, Dr. Mary Parke Manning, Thomas Manning, Diane Igleheart and Joan Talley; and by godson Andrew Curry. John W. F. Dulles, the Cardinal’s brother, and John Dulles’ wife of 68 years, Eleanor Ritter Dulles, both passed away at ages 95 and 91, respectively, in June 2008, in San Antonio, Texas.

In accordance with the traditions of the Church, the Cardinal’s death will be marked by the celebration of three Masses:

Tuesday, December 16, at 7:30 p.m. in the University Church

Wednesday, December 17, at 7:30 p.m. in the University Church

Thursday, December 18, at 2 p.m. at St. Patrick’s Cathedral

The members of the University family are invited to join the Jesuit Community at each of these Masses. Both Masses will be streamed live on the Web at: http://www.fordham.edu/Media

In addition, the Cardinal’s family will receive visitors in the University Church on Tuesday and Wednesday afternoons from 2 to 5 p.m.

In lieu of flowers, the New York Province of the Society of Jesus and Fordham University will accept donations in memory of Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., designated for the apostolic works of the Society of Jesus, or the Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., Chair in Catholic Theology, respectively. Gifts may be directed to:

The New York Province of the Society of Jesus

Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., Memorial Fund

39 East 83rd Street

New York, NY 10028

Debra A. Ryan

Associate Director of Development

(212) 774-5544 or [email protected]

OR

Fordham University

The Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., Chair in Catholic Theology

888 Seventh Ave., 8th Fl.

New York, NY 10019

Robert Smith

Senior Director of Development for Stewardship

(212) 636-7441 or [email protected]

The meeting took place in the suite of Edward Cardinal Egan, the archbishop of New York, after the Pope had greeted a group of disabled Catholic youths. The Pope “bounded into the room with a big smile on his face,” according to Anne-Marie Kirmse, O.P., Cardinal Dulles’ assistant, who was present for the meeting. “He went directly to where Cardinal Dulles was sitting, saying, ‘Eminenza, Eminenza, I recall the work you did for the International Theological Committee in the 1990s,’ and Cardinal Dulles kissed the papal ring and smiled back at the Pope,” Sister Kirmse said.

The Pope also greeted Thomas R. Marciniak, S.J., of the Fordham Jesuit community, who served as Cardinal Dulles’ priest chaplain for the meeting, the Cardinal’s medical attendants, and Sister Kirmse, she said. The Pontiff then sat next to Cardinal Dulles to hear his prepared remarks, read by Father Marciniak. Cardinal Dulles has been in poor health recently and was unable to speak for himself.

Father Marciniak presented the Pope with a copy of Cardinal Dulles’s recent book, Church and Society: The Laurence J. McGinley Lectures, 1988-2007 (Fordham University Press, 2008). The Pope expressed great interest in the book, Sister Kirmse said, and even interrupted the reading of the Cardinal’s remarks to ask again when the book had been published. The Pontiff eagerly looked through the book, and said he was touched by Cardinal Dulles’s inscription to him.

Before leaving, the Pope blessed Cardinal Dulles, assured him he was in the Pope’s prayers, and encouraged the Cardinal in his illness.

]]> Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., Ph.D., the Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society, will deliver his 39th McGinley lecture on Tuesday, April 1, at 8 p.m. at the Leonard Theatre, Fordham Preparatory School, on the Rose Hill campus in the Bronx. The lecture is titled, “Farewell Address as Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society (1988 – 2008).”

Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., Ph.D., the Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society, will deliver his 39th McGinley lecture on Tuesday, April 1, at 8 p.m. at the Leonard Theatre, Fordham Preparatory School, on the Rose Hill campus in the Bronx. The lecture is titled, “Farewell Address as Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society (1988 – 2008).”

A response to the lecture will be given by Rev. Robert P. Imbelli, Ph.D., associate professor of theology at Boston College.

Cardinal Dulles, who will stay on as the Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society Emeritus, has held the McGinley chair since 1988. Born in Auburn, N.Y., he is an internationally known author and lecturer. Named to the College of Cardinals by Pope John Paul II in 2001, he is the only United States-born theologian who is not a bishop ever to receive this honor. Cardinal Dulles has published 23 books and more than 800 articles, essays and reviews on theological topics.

The McGinley Chair in Religion and Society was established in 1985 to attract scholars interested in the intersection of religion with legal, political and cultural forces of society. In the past, Cardinal Dulles’ McGinley lectures have balanced controversial lay themes such as evolution, the death penalty and human rights with his exploration of church theology through topics like the challenge of the catechism and the mission of the laity.

Father Imbelli, a priest of the Archdiocese of New York, has written and commented widely on the theology and policies of John Paul and Pope Benedict. He is the editor of Handing on the Faith: the Church’s Mission and Challenge.

For more information, call (718) 817-4745 or email [email protected].

]]>